The Use of Prehospital Intensive Care Units in Emergencies—A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Protocol

2.2. Search Keywords and the Literature Search Strategy

- Prehospital: This word resulted in a diverse combination of emergency care and ambulances, all of which were already included in our search.

- Intensive Care: This keyword was associated with diverse critical care facilities, such as coronary critical care or pediatric critical care units, none of which were within the scope of this study.

- Emergency: This keyword resulted in terms related to emergency management of different medical conditions, emergency activities, or special subgroups, e.g., emergency medicine, trauma, etc.

2.3. Databases and Information Sources

2.4. Search Strings

2.4.1. The Primary Search String

- “Intensive Care Unit”[Mesh] OR “intensive care”[Title/Abstract] OR “ICU”[Title/Abstract]

- “Prehospital”[Title/Abstract] OR “Ambulance”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pre-hospital care”[Title/Abstract]

- “Emergencies”[Title/Abstract] OR “Emergency”[Title/Abstract] OR “Trauma”[Title/Abstract]

2.4.2. Final Search Strings

2.5. Collaborative Review Tool

2.6. Eligibility Criteria

2.7. Inclusion Criteria

2.8. Exclusion Criteria

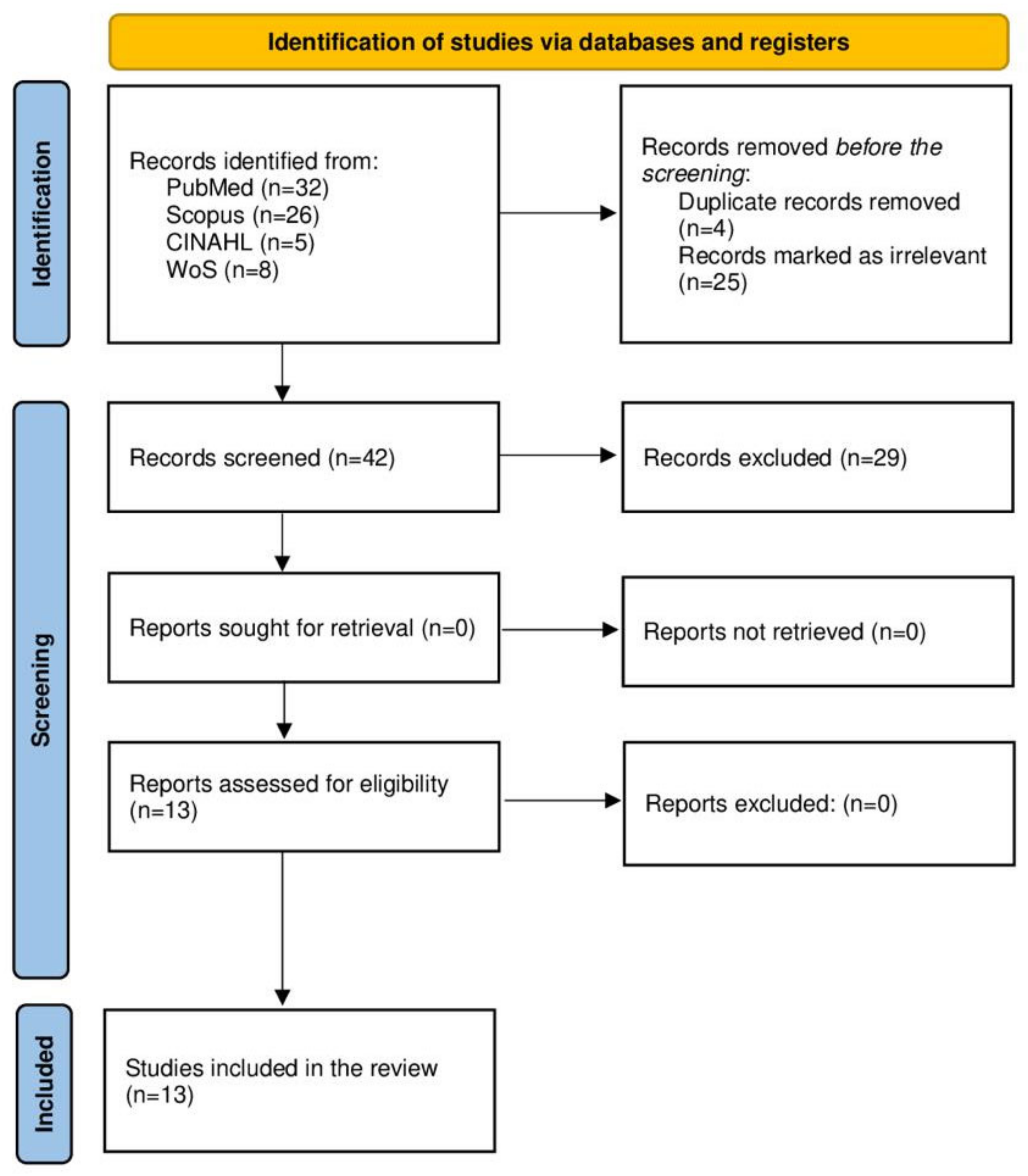

2.9. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.10. Review Process and Data Charting

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Reviewed Studies

3.2. PICU Configurations

3.2.1. Type and Size of the PICU

3.2.2. Personnel

3.2.3. Training

3.2.4. Equipment

3.3. Protocols and Practices of the PICU

3.3.1. Protocols

3.3.2. Dispatch Process and Practice

3.3.3. Assessment and Triage

3.3.4. Clinical Procedures

3.3.5. Communication and Transportation

3.4. Benefits of PICUs in Trauma Care

3.5. Challenges and Research Priorities for PICUs in Trauma Care

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Primary Search Strategy and Its Outcomes

References

- Rossiter, N.D. Trauma—The forgotten pandemic? Int. Orthop. SICOT 2022, 46, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prottengeier, J.; Albermann, M.; Heinrich, S.; Birkholz, T.; Gall, C.; Schmidt, J. The prehospital intravenous access assessment: A prospective study on intravenous access failure and access delay in prehospital emergency medicine. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X.; Chen, K.J.; Zhu, H.T.; Lin, A.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Liu, L.C.; Ji, R.; Chan, F.S.; Fan, J.K. Preventable Deaths in Multiple Trauma Patients: The Importance of Auditing and Continuous Quality Improvement. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, D.; Maruyama, S.; Yoshihara, T.; Saito, F.; Yoshiya, K.; Nakamori, Y. Hybrid emergency room: Installation, establishment, and innovation in the emergency department. Acute Med. Surg. 2023, 10, e856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, A.; Nakahara, S.; Bagaria, D.; De Silva, S.; De Silva, S.L.; Llaneta, A.; Pattanarattanamolee, R.; Li, Y.; Hoang, B.H. Focused research in emergency medical systems in Asia: A necessity for trauma system advancement. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 2, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, N.; Doughty, H.A.; Bishop, J.R.B.; Desai, A.; Dixon, E.F.; Hancox, J.M.; Herbert, M.J.; Leech, C.; Lewis, S.J.; Nash, M.R.; et al. Resuscitation with blood products in patients with trauma-related hemorrhagic shock receiving prehospital care (RePHILL): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e250–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravi, M.R.; Carlström, E.; Örtenwall, P.; Khorram-Manesh, A. Prehospital Assessment of Non-Traumatic Abdominal Pain. Iran. Red. Cresc. Med. J. 2021, 23, e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haner, A.; Örninge, P.; Khorram-Manesh, A. The role of physician-staffed ambulances: The outcome of a pilot study. J. Acute Dis. 2015, 4, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vopelius-Feldt, J.; Benger, J. Who does what in prehospital critical care? An analysis of competencies of paramedics, critical care paramedics, and prehospital physicians. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Wennman, I.; Andersson, B.; Dahlén Holmqvist, L.; Carlson, T.; Carlström, E. Reasons for longer LOS at the emergency departments: Practical, patient-centered, medical, or cultural? Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2019, 34, e1586–e1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raidla, A.; Darro, K.; Carlson, T.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Berlin, J.; Carlström, E. Outcomes of Establishing an Urgent Care Centre in the Same Location as an Emergency Department. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, C.D.; King, P.; Thompson, F. Prehospital advanced airway management by ambulance technicians and paramedics: Is clinical practice sufficient to maintain skills? Emerg. Med. J. 2009, 26, 888–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, G.; Martin, I.; Smith, M. Trauma: Who Cares? A Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. 2007. Available online: http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2007report2/Downloads/SIP_summary.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2012).

- Tran, T.T.; Lee, J.; Sleigh, A.; Banwell, C. Putting Culture into Prehospital Emergency Care: A Systematic Narrative Review of Literature from Lower Middle-Income Countries. Prehosp. Disaster. Med. 2019, 34, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, P.; Mackenzie, R.; Ng, G.; Reid, C.; Pearson, G. Availability and utilization of physician-based pre-hospital critical care support to the NHS ambulance service in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Emerg. Med. J. 2012, 29, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahara, S.; Hoang, B.H.; Mayxay, M.; Pattanarattanamolee, R.; Jayatilleke, A.U.; Ichikawa, M.; Sakamoto, T. Development of an emergency medical system model for resource-constrained settings. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callese, T.E.; Richards, C.T.; Shaw, P.; Schuetz, S.J.; Paladino, L.; Issa, N.; Swaroop, M. Trauma system development in low- and middle-income countries: A review. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 193, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisborg, T.; Murad, M.K.; Edvardsen, O.; Husum, H. Prehospital trauma system in a low-income country: System maturation and adaptation during 8 years. J. Trauma 2008, 64, 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Lubarsky, S.; Varpio, L.; Durning, S.J.; Young, M.E. Scoping reviews in health professions education: Challenges, considerations and lessons learned about epistemology and methodology. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2020, 25, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Connecticut. Find Information—Revising and Refining Your Search. Available online: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/findinformation/revising (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Bramer, W.M.; de Jonge, G.B.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Mast, F.; Kleijnen, J. A systematic approach to searching: An efficient and complete method to develop literature searches. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2018, 106, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andruszkow, H.; Schweigkofler, U.; Lefering, R.; Frey, M.; Horst, K.; Pfeifer, R.; Beckers, S.K.; Pape, H.C.; Hildebrand, F. Impact of helicopter emergency medical service in traumatized patients: Which patient benefits most? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, C.; Miller, M.; Johnson, T.; Burns, B.; Fogg, T.; Sarrami, P.; Singh, H.; Dee, K.; Dinh, M. Prehospital activation of a coordinated multidisciplinary hospital response in preparation for patients with severe hemorrhage: A statewide data linkage study of the New South Wales “Code Crimson” pathway. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022, 93, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.M.; Jepsen, S.B.; Mikkelsen, S.; Rehn, M. The Great Belt train accident: The emergency medical services response. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2021, 29, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewdson, K.; Heywoth, A.; Rehn, M.; Sadek, S.; Lockey, D. Apnoeic oxygenation for emergency anaesthesia of pre-hospital trauma patients. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2021, 29, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heschl, S.; Meadley, B.; Andrew, E.; Butt, W.; Bernard, S.; Smith, K. Efficacy of pre-hospital rapid sequence intubation in paediatric traumatic brain injury: A 9-year observational study. Injury 2018, 49, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.A.; Douglass, K.A.; Ejas, S.; Poovathumparambil, V. Development and Implementation of a Novel Prehospital Care System in the State of Kerala, India. Prehosp. Disaster. Med. 2016, 31, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, S.; Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, C.; Binderup, L.G.; Lossius, H.M.; Toft, P.; Lassen, A.T. Termination of prehospital resuscitative efforts: A study of documentation on ethical considerations at the scene. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2017, 25, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadley, B.; Heschl, S.; Andrew, E.; De Wit, A.; Bernard, S.A.; Smith, K. A paramedic-staffed helicopter emergency medical service’s response to winch missions in Victoria, Australia. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2016, 20, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heschl, S.; Andrew, E.; de Wit, A.; Bernard, S.; Kennedy, M.; Smith, K.; Study Investigators. Prehospital transfusion of red cell concentrates in a paramedic-staffed helicopter emergency medical service. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2018, 30, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, S.; Krüger, A.J.; Zwisler, S.T.; Brøchner, A.C. Outcome following physician supervised prehospital resuscitation: A retrospective study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissier, C.; Bonithon-Kopp, C.; Freysz, M. French Intensive care Recorded in Severe Trauma (FIRST) study group. Statement of severe trauma management in France: Teachings of the FIRST study. In Annales Françaises D’anesthésie et de Réanimation; Elsevier Masson: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 32, pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.; Hansen, C.M.; Rasmussen, L.S. Airway management in unconscious non-trauma patients. Emerg. Med. J. 2012, 29, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, H.; Sato, T.; Morita, S.; Nakagawa, Y.; Inokuchi, S. A case of blunt traumatic cardiac tamponade successfully treated by out-of-hospital pericardial drainage in a “doctor-helicopter” ambulance staffed by skilled emergency physicians. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2016, 41, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.; Williams, T.A.; Tohira, H.; Bailey, P.; Finn, J. Epidemiology of trauma patients attended by ambulance paramedics in Perth, Western Australia. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2018, 30, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hick, J.L.; Barbera, J.A.; Kelen, G.D. Refining surge capacity: Conventional, contingency, and crisis capacity. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2009, 3, S59–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, B.H.; Mai, T.H.; Dinh, T.S.; Nguyen, T.; Dang, T.A.; Van, C.L.; Luong, Q.C.; Nakahara, S. Unmet Need for Emergency Medical Services in Hanoi, Vietnam. JMA J. 2021, 4, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, G.; Hansmann, A.; Aziz, O.; O’Brien, N. Survey of resources available to implement severe pediatric traumatic brain injury management guidelines in low and middle-income countries. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2020, 36, 2647–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram-Manesh, A. Facilitators and constrainers of civilian–military collaboration: The Swedish perspectives. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2020, 46, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, A.; Jones, A.; Marcus, S.; Nordmann, G.; Pope, C.; Reavley, P.; Smith, C. Current controversies in military pre-hospital critical care. BMJ Mil. Health 2011, 157 (Suppl. 3), S305–S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadley, B.; Olaussen, A.; Delorenzo, A.; Roder, N.; Martin, C.; St Clair, T.; Burns, A.; Stam, E.; Williams, B. Educational standards for training paramedics in ultrasound: A scoping review. BMC Emerg. Med. 2017, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frostick, E.; Johnson, C. Pre-hospital emergency medicine and the trauma intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2019, 20, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meizoso, J.P.; Valle, E.J.; Allen, C.J.; Ray, J.J.; Jouria, J.M.; Teisch, L.F.; Shatz, D.V.; Namias, N.; Schulman, C.I.; Proctor, K.G. Decreased mortality after prehospital interventions in severely injured trauma patients. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 79, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, B.; Nathens, A.B. Pro/con debate: Is the scoop and run approach the best approach to trauma services organization? Crit. Care 2008, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner, G.; Lowe, T.; Rawcliffe, D.; Wellman, N. Trauma for all: A pilot study of the subjective experience of physical restraint for mental health inpatients and staff in the UK. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2002, 9, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkler, M.A.; Furdock, R.J.; Vallier, H.A. Treating trauma more effectively: A review of psychosocial programming. Injury 2022, 53, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.O.; Teuben, M.P.J.; Lefering, R.; Halvachizadeh, S.; Mica, L.; Simmen, H.P.; Pfeifer, R.; Pape, H.C.; Sprengel, K.; TraumaRegister DGU. Pre-hospital trauma care in Switzerland and Germany: Do they speak the same language? Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 47, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelsson, A.; Rystedt, I.; Suserud, B.O.; Lindwall, L. Learning by simulation in prehospital emergency care—An integrative literature review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Berlin, J.; Carlström, E. Two Validated Ways of Improving the Ability of Decision-Making in Emergencies; Results from a Literature Review. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2016, 4, 186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Lennquist Montán, K.; Hedelin, A.; Kihlgren, M.; Örtenwall, P. Prehospital triage, the discrepancy in priority-setting between emergency medical dispatch centre and ambulance crews. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2011, 37, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.M.; Conn, A.K. Prehospital care—Scoop and run or stay and play? Injury 2009, 40, S23–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, A.S.; Sollid, S.J.; Vigerust, T.; Jystad, M.; Rehn, M. Helicopter emergency medical services in major incident management: A national Norwegian cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (YOP) | Study Objectives | PICU Configuration * | Criteria for Activation | Beneficiary/Target Patient Population | Performed Procedure Enroute (on Field) | Outcome | Risk–Safety | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andruszkow (2016) [26] | - Examine whether age, gender, injury mode/severity would help identify trauma patient populations who might benefit explicitly from HEMS rescue. | - HEMS and GEMS physicians are trained standardly in ATLS and PHTLS in Germany. | NR | Special subgroups: - middle-aged and older patients (>55 years) - low-energy trauma - minor-severity injuries These subgroups witnessed the best survival potential provided by HEMS. | Six on-scene procedures were documented in the TR-DGU: - intubation - chest tube insertion - vasopressors, sedatives, or volume infusion - CPR | - HEMS rescues improve overall survival compared to GEMS. | NR | NR |

| Partyka (2016) [27] | - Describe the clinical characteristics of patients who had PH trauma CC activation in the first 23 months of a statewide policy implementation (main outcome: hemorrhage control). - Compare these characteristics to trauma patients transported by retrieval services who met the CC criteria but whose PH CC was not activated (“missed code crimson”). | NR | NR | - Code Crimson-activated patients had more multisystem trauma (80%), especially thoracic trauma (hemopneumothorax, multiple rib fractures, pulmonary contusion) and femoral fractures, compared with the missed CC patients. - Greater degree of hemodynamic instability in the CC-activated group, with a higher shock index. | - intubation (60/72) - chest decompression (39/72) - positive eFAST (30/72) - blood products consistent with CC criteria (71/72) | - In-hospital mortality rate was lower in CC-activated patients (20% vs. 33–48%). | NR | NR |

| Hansen (2016) [28] | - Describe immediate PH EMS response to the Great Belt Train Accident. - Evaluate adherence to guidelines to identify areas for improvement for future MI management. | - The EMS in Denmark is a three-tiered system consisting of ambulances manned by a combination of EMT with basic, intermediate, or PM levels of training. - The Danish EMS includes rapid response units manned by PMs and MECUs staffed by specialists in anesthesiology with a sub-specialization in PH critical care. - A supplementary physician-manned HEMS is also available. | - EMS response relies on a systematic criteria-based dispatch protocol. | - No patients required transport over longer distances, and their injuries did not require extensive medical treatment at the scene. Therefore, HEMS helicopters were cancelled on-scene. | - 2 rescue teams (1 EMS physician and 2 EMT/PMs) entered the train from the east end and triaged the patients inside the coaches as per physician discretion using anatomical triage. - Transition from the pre- to in-hospital phase in MI should be seamless, which requires predefined plans and systems for trauma management. | - EMCC physician decided to allocate all passengers to the same hospital once the Medical Incident Commander established the magnitude of the MI. - Reports from other major European incidents underline command and control in every phase as an essential component. | - Weather conditions may potentially compromise EMS personnel’s safety and influence patient transfers from the accident site. | - Time from dispatch to arrival was compromised because of traffic congestion on both sides of the connection. |

| Crewdson (2016) [29] | - Investigate whether the introduction of apneic oxygenation would reduce the frequency of desaturation in trauma patients undergoing prehospital emergency airway management. | - Doctor–PM teams are delivered by helicopter and fast-response cars. - Flight PMs in the ambulance control room dispatch services (target critically ill or injured patients). - A ground ambulance is also always dispatched. | - The ambulance control room dispatches the services, and specific criteria target critically ill or injured patients. | - Advanced airway interventions are necessary for a small subgroup of severely injured patients. | - Nasal oxygenation using low-flow nasal prongs is a low-risk, easily administered procedure for passive apneic oxygenation in the pre-intubation and peri-intubation phases of emergency anesthesia. | - Apneic oxygenation reduced the frequency of peri-intubation hypoxia (SpO2 ≤ 90%) in patients with initial SpO2 > 95% (p = 0.0001). - Also, the recovery phase improved in patients with severe hypoxia prior to intubation. | - Peri-intubation hypoxia (SpO2 ≤ 90%) is documented in prehospital advanced airway interventions (the most frequent AE). - Hypoxia occurred in 9.2% of patients during the first attempt at intubation in an emergency setting, reaching 37.8% upon repeated intubation. | NR |

| Heschl (2016) [30] | - Describe mortality and functional outcomes after 6 months in children with TBI (PH RSI by HEMS PMs vs. no intubation). | - Ambulance Victoria provides road ambulances and 5 emergency helicopters throughout the state. - The system is two-tiered, with ALS PMs and/or ICPs. - ICPs are trained to perform ETI in adults and pediatrics (i.e., respiratory arrest, cardiac arrest, and impaired consciousness). | NR | - Pediatric patients with suspected TBI. | - PM airway management includes ETI without drugs or RSI. | - No difference in the unadjusted mortality rate or functional outcome after 6 months between both groups. | - Intubation success rate was 99% (86/87), with a first-pass success rate of 93% (81/87). | NR |

| Brown (2016) [31] | - Describe the epidemiology of trauma attended by PMs in Western Australia. - Describe trauma incidence and mortality rates and trends. - To compare the characteristics of patients (died at the scene vs. died on the day of injury vs. died within 30 days of the event vs. survived 30 days). - To report interventions performed by PMs. | - St. John Ambulance WA within the metropolitan area: ambulances are staffed by PMs providing PH care (i.e., ALS), guided by CPG. | NR | - Patients transported with the highest acuity level accounted for 2.7%. | - ALS (i.e., endotracheal intubation, surgical). | NR | NR | - The lack of PM exposure to high-acuity patients, the resulting skill decay, and decreasing job satisfaction have previously been reported. |

| Mikkelsen (2016) [32] | - Investigate to what extent ethical considerations are documented in discharge summaries in cases of life-and-death decisions made by emergency care anesthesiologists in a Danish PH setting. - Describe the nature of such considerations and seek the establishment of suggested recommendations. | - MECU in Odense is a part of a three-tiered system that supplements an ordinary ambulance manned by two EMTs or an ambulance assisted by a PM. - It consists of 1 rapid-response car, operating all year round, manned by a specialist in anesthesiology and an EMT. | NR | - Patients in cardiac arrest. | - In Denmark, as in most other countries, physicians are responsible for the act of declaring a patient dead in the PH field. | - In most cases where ethical content was identified, ethical considerations led to a decision to terminate treatment. | NR | - PH physicians may face ethical dilemmas in life-and-death decisions. - An EMT or PM is obliged to initiate resuscitative efforts for all lifeless patients until declared dead by a physician. - All lifeless patients are legally regarded as not dead but as patients with cardiac arrest. |

| Meadley (2016) [33] | - Define the characteristics of winch missions undertaken by ICFPs in Victoria, Australia, with a focus on extraction methods and clinical care delivered at the scene. | - All 5 aircraft (4 Bell 412EP and 1 air-bus Dauphine N3) are capable of winch operations, operating 24/7. | NR | - 109 (87.2%) patients experienced trauma with a mean revised trauma score of 7.52. - Isolated limb fractures were the most common injuries, whereas falls and vehicle-related trauma were the most common mechanisms of injury. | - Vascular access (38.4%), analgesia (44.0%), and anti-emetic administration (28.8%) were the most common interventions. | NR | - Winch benefits must be weighed against the risk of injury and/or fatality to both crew and patients. - Training for and maintaining updated winch operations incurs a significant financial and operational burden. | NR |

| Heschl (2016) [34] | - Describe the implementation and initial experience of RCC administered in a PM-staffed HEMS in Victoria, Australia. | - Primary missions: helicopters staffed with one pilot, an air crewman, and an ICFP. - The latter undergo extensive training to be qualified to treat critically ill patients compared with road-based PMs. - Their skillset includes advanced airway management by RSI and cricothyroidotomy, comprehensive analgesia (i.e., opioids, ketamine), and the administration of vasoactive medications. - HEMS carries point-of-care devices to measure ABG and Hb. | NR | - 150 patients received PH RCCs, of which 136 suffered trauma. - 66.7% of them were males, and 62.5% of them were involved in car accidents. - 97.4% had an ISI ≥ 12. | - Advanced airway management (RSI), cricothyroidotomy, analgesia (i.e., opioids, ketamine), and vasoactive drug administration. | - SBP (80 mmHg vs. 94 mmHg, p < 0.001) and shock index (1.50 vs. 1.23, p < 0.001) improved between the time of consultation and arrival at the hospital. - Trauma-related mortality was 37.7%. - No transfusion-related complications were identified. | - To assure optimal safety, consultation was required with an ARV physician coordinator prior to the administration of RCC. - Main indication for RCC administration was refractory hypovolemic shock after 40 mL/kg administration of crystalloid fluids. - Each helicopter carries 4 RCC units equipped with a temperature data logger that records the temperature every minute. - Maintenance of storage temperature 2–8 °C is achieved by refrigerated gel pads (exchanged twice daily). | NR |

| Mikkelsen (2016) [35] | - To determine patients’ survival between a specialized physician at the scene and an EMT or PM. | - Anesthesiologist-administered PH therapy increases the level of treatment modalities. - In May 2006, a MECU was initiated in Odense, Denmark, consisting of a rapid-response car operating all year round. It is manned by a specialist anesthesiologist and an EMT. - It operates as part of a two-tiered system in which the MECU supplements an ordinary ambulance manned by 2 EMTs. | -The criteria for denoting a case as ‘patient undergoing life-saving measures’ included: Explicit criteria: - Intubation or other airway procedures exceeding the competence of the PM or EMTs. - Advanced medical treatment exceeding the competence of the PM or EMTs in cardiac arrest and/or defibrillation. Implicit criteria: - Advanced medical treatment and fluid resuscitation exceeding the competence of the attending PM in severe shock states and severe hypovolemia, respectively. | - Survivors of critical illness or those with post-intensive care syndrome (most benefited from peer support groups). | - Intubation/other airway procedures exceeding the competency of PMs or EMTs. - Advanced medical treatment exceeding the competence of the PM or EMTs in cardiac arrest and/or defibrillation when indicated by the attending physician. Implicit criteria: - Advanced medical treatment and fluid resuscitation exceeding the competence of the attending PM in severe shock states and severe hypovolemia, respectively. | - 37.8% of patients were discharged to their own homes following in-hospital treatment. | NR | NR |

| Tissier (2016) [36] | - Study the impact of medical prehospital management (SMUR vs. fire brigades) on the 30-day mortality of severe blunt trauma victims. - Examine the influence of the mode of transport by SMUR (air vs. ground ambulance). - Evaluate patients’ outcomes based on (1) the level of hospitalization at the time of first admission and (2) the pattern of early surgical and medical procedures. - Evaluate the use of the motor component of GCS on the performance of prehospital triage scores. | NR | NR | - Heli-SMUR patients were more severely injured, but the ISS was similar between groups. - Hypotension and severe spinal injuries were more frequent in heli-SMUR patients than in ground-SMUR patients. | - SMUR allows a variety of therapeutic strategies involving ALS care. - EPs can perform rapid sequence induction before endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation, sedative and analgesic drug administration, pleural exsufflation, appropriate fluid loading, and osmotherapy. | - Risk of death before ICU discharge (within 30 days) was significantly lower for heli-SMUR patients than for ground-SMUR patients after adjustment of initial status, ISS, and overall surgical procedures. | - The median time to hospital admission was higher for heli-SMUR than ground-SMUR patients (2.3 vs. 1.8 h, respectively). | NR |

| Nielsen (2016) [37] | - Describe the experience of airway management in unconscious non-trauma patients in the PH setting with a physician-manned MECU. - Main outcome: the need for subsequent tracheal intubation during hospitalization after initial treatment. | - MECU is manned by a team consisting of a medical doctor and a specially trained ALS provider. - Doctors on MECUs are all specialists in anesthesiology, with at least 7 years of postgraduate experience and a minimum of 5 years of specialty training. | NR | - Unconscious (GCS scores < 9) non-trauma patients. | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Otsuka (2016) [38] | - A report of a blunt-trauma patient’s life by diagnosing traumatic cardiac tamponade and performing immediate pericardial drainage in a doctor-helicopter. | - PH diagnosis of cardiac tamponade and performance of pericardial drainage by a skilled EMP transported to the field by doctor-helicopter ambulance, followed by transportation of patients to a critical care center, may prevent PH deaths from cardiac trauma. | NR | - Blunt-trauma patient’s life by diagnosing traumatic cardiac tamponade. | - Immediate pericardial drainage using a portable US device at the heliport prior to transfer. | - Save this blunt-trauma patient’s life by diagnosing traumatic cardiac tamponade and performing immediate pericardial drainage using a portable US at the heliport prior to hospital transfer. | NR | - Cardiac tamponade is one of the main causes of death before hospital arrival in cases of chest trauma; late diagnosis and treatment can be fatal. - FAST is useful for the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade, and a portable US device can be used anywhere. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alruwaili, A.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Ratnayake, A.; Robinson, Y.; Goniewicz, K. The Use of Prehospital Intensive Care Units in Emergencies—A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212892

Alruwaili A, Khorram-Manesh A, Ratnayake A, Robinson Y, Goniewicz K. The Use of Prehospital Intensive Care Units in Emergencies—A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212892

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlruwaili, Abdullah, Amir Khorram-Manesh, Amila Ratnayake, Yohan Robinson, and Krzysztof Goniewicz. 2023. "The Use of Prehospital Intensive Care Units in Emergencies—A Scoping Review" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212892

APA StyleAlruwaili, A., Khorram-Manesh, A., Ratnayake, A., Robinson, Y., & Goniewicz, K. (2023). The Use of Prehospital Intensive Care Units in Emergencies—A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 11(21), 2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212892