Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Interprofessional Assessment to Inform Person-Centered Participative Care—An Osteopathic Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

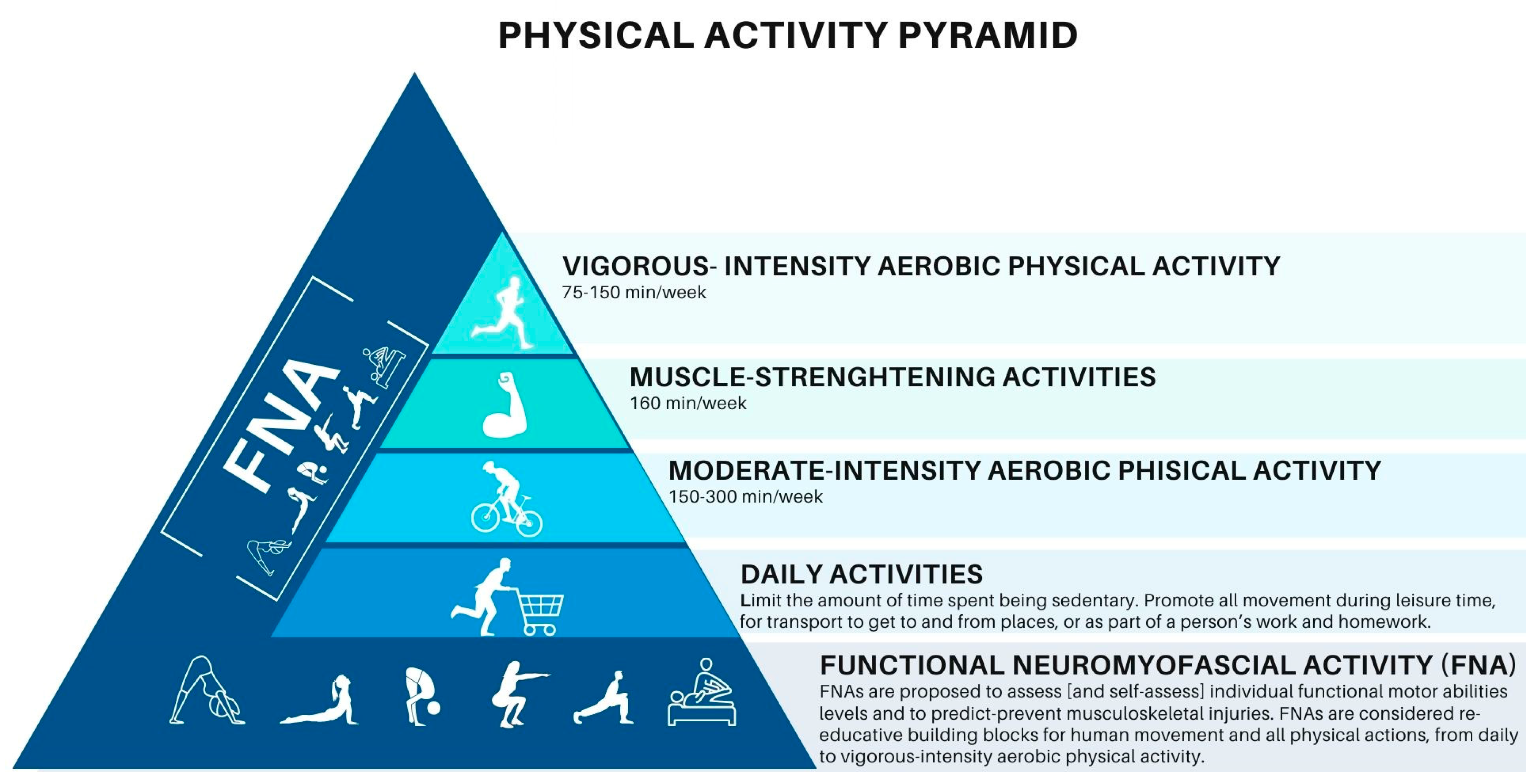

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. History and Evolution of Patient Active–Participative Approaches in the Osteopathic Field

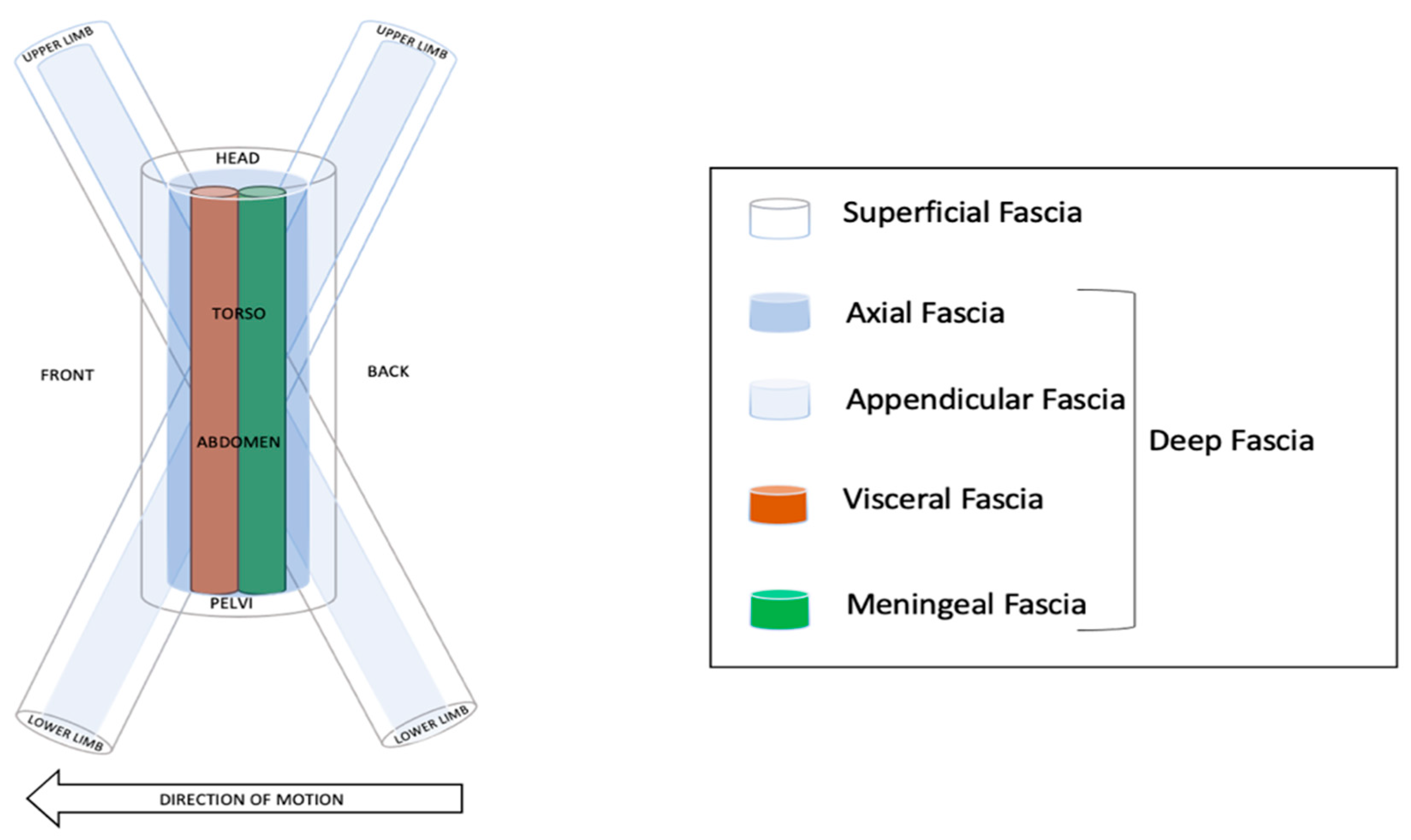

3.2. Movement Organization and Motor Abilities: The Role of the Neuromyofascial System

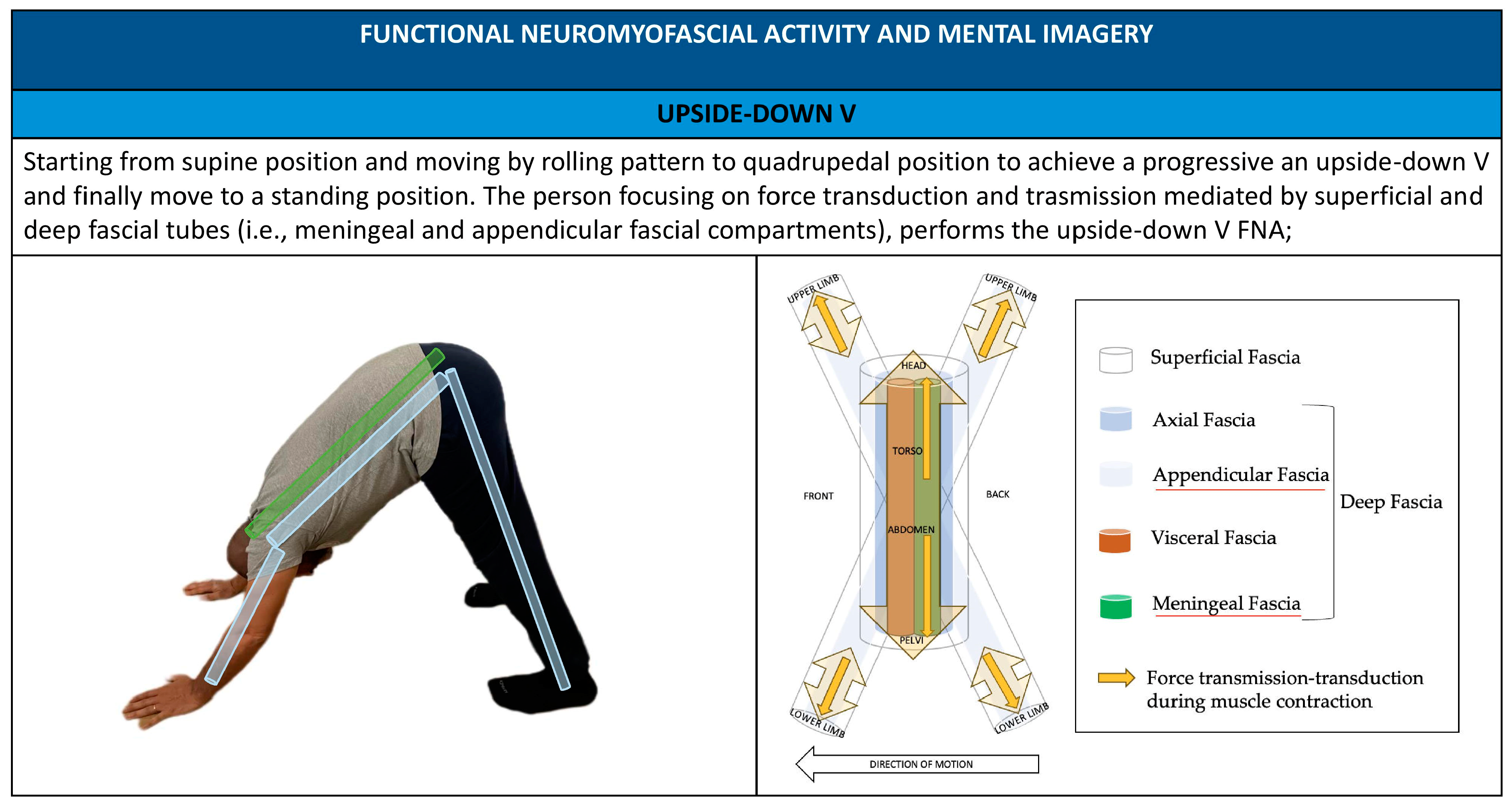

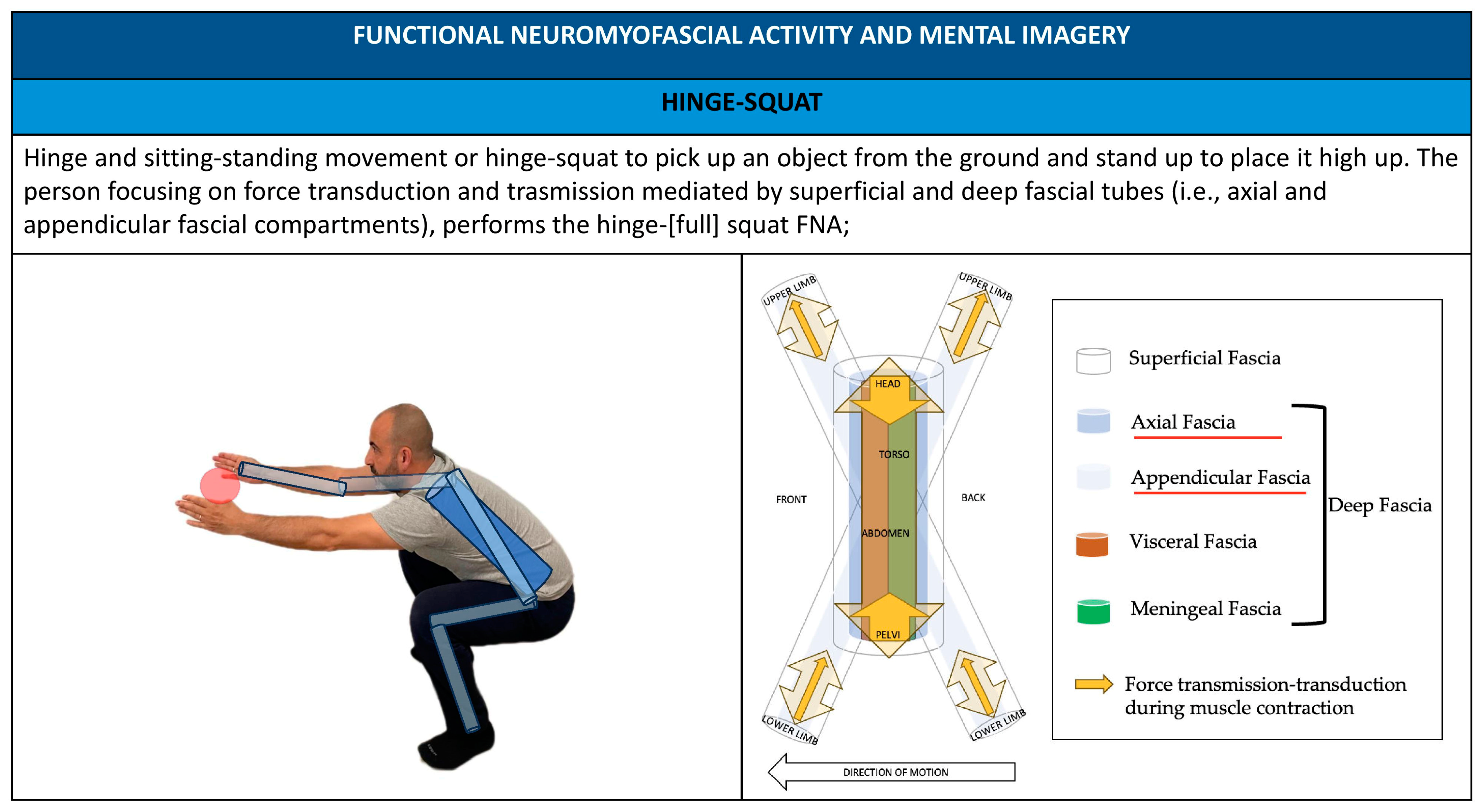

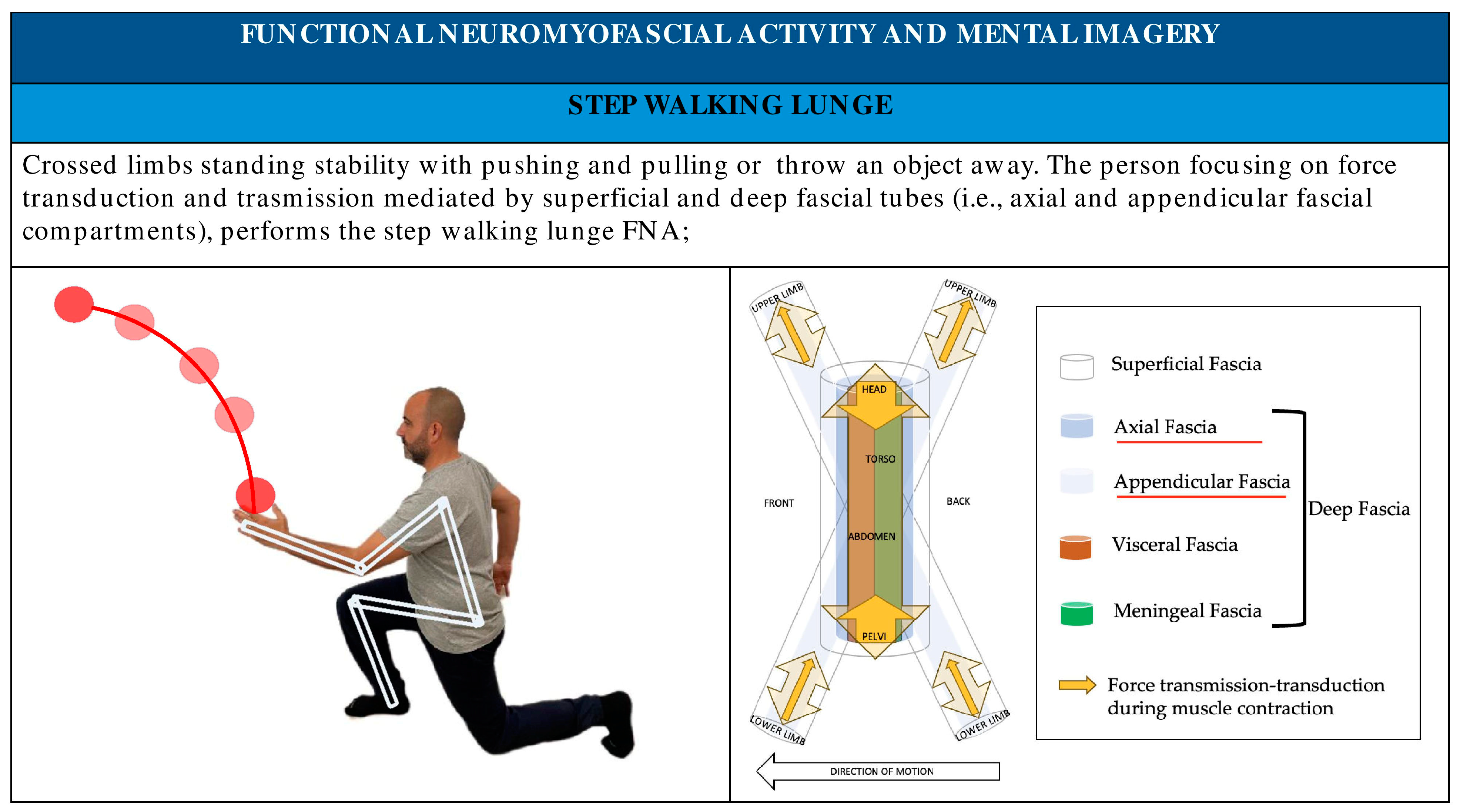

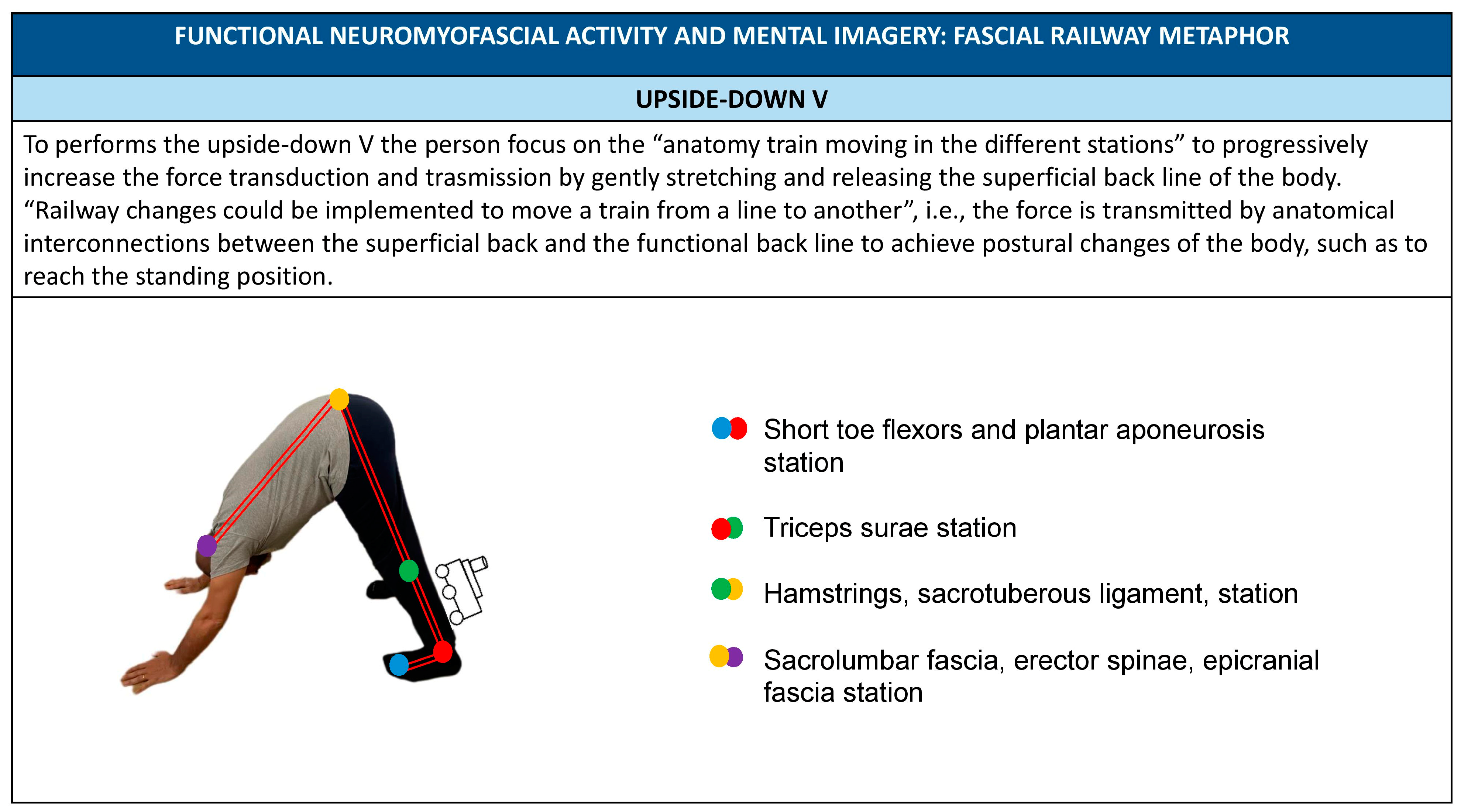

3.3. Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Motion Assessment to Inform Osteopathic Person-Centered Care

- -

- Evaluate functional motor abilities, with coordination and fluidity occurring during the execution of a requested movement to determine motor skills and promptness in carrying out daily actions, from home activities to physical exercise and sports;

- -

- -

- Inform the comprehensive assessment of the person in which movement and palpatory findings are considered key elements. The assessment of motor dysfunctions and movement inabilities is refined and informed by an osteopathic palpatory evaluation for somatic dysfunction and fascial patterns. Somatic dysfunction is defined as an alteration in the body functions related to a region of the body framework, showing a lack of movement coordination [19]. The fascial patterns are considered as an altered body function associated with the whole body, showing a lack of movement coordination [19].

- -

- Evaluate readiness to return to daily activities and physical activity at the end of osteopathic treatment and/or rehabilitation and/or re-education after an injury or surgery;

- -

- Obtain elements concerning the prevention of injuries and the predictability of performance;

- -

- Provide personalized, specific, and functional recommendations for osteopathic treatment and exercise programs;

- -

- Better share with the patients and other health professionals the outcome of the osteopathic assessment of musculoskeletal and associated functions and the aim of the treatment planning for agency and health maintenance.

3.4. Proposed Functional Neuromyofascial Activity Scoring

- -

- A score of three points is given when during the execution of a single FNA the patients show signs of functional motor abilities. The patients share with the osteopath their perception regarding coordination and fluidity of the movement during the execution of requested fascia-oriented movements. There is an observable coordination and fluidity with fascia-oriented motions during the execution of an FNA.

- -

- A score of two is given when during the execution of a single FNA the patients show signs of regional motor dysfunction, lack of coordination and fluidity, and an inability to use principles of fascia-oriented exercise in a specific body area. Only following external and/or internal regional touch-based cues provided by the osteopath (e.g., head, cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, pelvic, lower and upper extremities, rib cage, abdomen, and other regions) is there an emergent patient perception and an osteopath observation of better coordination and fluidity during the execution of the requested FNA performed with fascia-oriented movements.

- -

- A score of one is given when during the execution of a single FNA the patients show signs of general motor dysfunction, lack of coordination and fluidity, and an inability to use principles of fascia-oriented exercise in the whole body. Only following external and/or internal global touch-based cues provided by the osteopath (e.g., fascial compartments associated with functional myofascial chains) is there an emergent patient perception and an osteopath observation of better coordination and fluidity during the execution of the requested FNA performed with fascia-oriented movements.

- -

- A score of zero points is given when the patients show movement inabilities and report diffused pain in the body; consequently, it is not possible to finalize the requested movement.

3.5. Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Score Interpretation Proposal

3.6. Functional Neuromyofascial Activity as Patient Active–Participative Osteopathic Approaches

3.7. Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Mental Imagery and Metaphors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.Z.; Fritz, J.M.; Silfies, S.P.; Schneider, M.J.; Beneciuk, J.M.; Lentz, T.A.; Gilliam, J.R.; Hendren, S.; Norman, K.S. Interventions for the Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, CPG1–CPG60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, N.N.; Candido, K.D.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Van Zundert, J.; Cohen, S.P. Low Back Pain. Lancet 2021, 398, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutting, N.; Caneiro, J.P.; Ong’wen, O.M.; Miciak, M.; Roberts, L. Person-Centered Care for Musculoskeletal Pain: Putting Principles into Practice. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2022, 62, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consorti, G.; Castagna, C.; Tramontano, M.; Longobardi, M.; Castagna, P.; Di Lernia, D.; Lunghi, C. Reconceptualizing Somatic Dysfunction in the Light of a Neuroaesthetic Enactive Paradigm. Healthcare 2023, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Evans, R.; Maiers, M.; Schulz, K.; Leininger, B.; Bronfort, G. Spinal manipulative therapy and exercise for older adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2019, 27, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, J.M.; Kongsted, A. A New Paradigm for Musculoskeletal Pain Care: Moving beyond Structural Impairments. Conclusion of a Chiropractic and Manual Therapies Thematic Series. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2023, 31, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunghi, C.; Tozzi, P.; Fusco, G. The Biomechanical Model in Manual Therapy: Is There an Ongoing Crisis or Just the Need to Revise the Underlying Concept and Application? J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2016, 20, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, E. The Fall of the Postural-Structural-Biomechanical Model in Manual and Physical Therapies: Exemplified by Lower Back Pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2011, 15, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetley, M. Instinctive Sleeping and Resting Postures: An Anthropological and Zoological Approach to Treatment of Low Back and Joint Pain. BMJ 2000, 321, 1616–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallden, M.; Sisson, M. Modern Disintegration and Primal Connectivity. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, P. The Contractile Field—A New Model of Human Movement. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2007, 11, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einspieler, C.; Prayer, D.; Marschik, P.B. Fetal Movements: The Origin of Human Behaviour. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, B.; Stanghelle, J.K. The Senior Fitness Test. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Kobesova, A.; Kolar, P. Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization & Sports Rehabilitation. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 8, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, G.; Burton, L.; Hoogenboom, B.J.; Voight, M. Functional Movement Screening: The Use of Fundamental Movements as an Assessment of Function—Part 1. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 9, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, G.; Burton, L.; Hoogenboom, B.J.; Voight, M. Functional Movement Screening: The Use of Fundamental Movements as an Assessment of Function—Part 2. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 9, 549–563. [Google Scholar]

- Goshtigian, G.R.; Swanson, B.T. Using The Selective Functional Movement Assessment And Regional Interdependence Theory To Guide Treatment Of An Athlete With Back Pain: A Case Report. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 11, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baroni, F.; Tramontano, M.; Barsotti, N.; Chiera, M.; Lanaro, D.; Lunghi, C. Osteopathic Structure/Function Models Renovation for a Person-Centered Approach: A Narrative Review and Integrative Hypothesis. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2021, 20, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, F.; Esteves, J.E. An Enactive–Ecological Model to Guide Patient-Centered Osteopathic Care. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collebrusco, L.; Lombardini, R. What About OMT and Nutrition for Managing the Irritable Bowel Syndrome? An Overview and Treatment Plan. Explore 2014, 10, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunghi, C.; Baroni, F.; Amodio, A.; Consorti, G.; Tramontano, M.; Liem, T. Patient Active Approaches in Osteopathic Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groisman, S.; Malysz, T.; De Souza Da Silva, L.; Rocha Ribeiro Sanches, T.; Camargo Bragante, K.; Locatelli, F.; Pontel Vigolo, C.; Vaccari, S.; Homercher Rosa Francisco, C.; Monteiro Steigleder, S.; et al. Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment Combined with Exercise Improves Pain and Disability in Individuals with Non-Specific Chronic Neck Pain: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Baroni, F.; Lunghi, C.; Dupuis, D. Historical Osteopathic Principles and Practices in Contemporary Care: An Anthropological Perspective to Foster Evidence-Informed and Culturally Sensitive Patient-Centered Care: A Commentary. Healthcare 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchesi, G.L.S.; Da Silva, A.K.F.; Amaral, O.H.B.; De Paula, V.C.G.; Jassi, F.J. Effects of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment Associated with Pain Education and Clinical Hypnosis in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain: Study Protocol for a Randomized Sham-Controlled Clinical Trial. Trials 2022, 23, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseman, E.H.; Whipps, J.; Howe, C.A.; Beverly, E.A. First-Year Osteopathic Medical Students’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Physical Activity. J. Osteopath. Med. 2018, 118, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, C. Guidelines for Writing a Commentary. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being 2016, 11, 31390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Prietula, M.J.; Cokely, E.T. The Making of an Expert. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Hazzard, C.; Osteopathy, A.S. The Practice and Applied Therapeutics of Osteopathy; Andesite Press: Lebanon, CT, USA, 1900; ISBN 978-1-296-51925-4. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, C.P. (Ed.) Clinical Osteopathy: The A. T. Still Research Institute; Kessinger Publishing, LLC: Whitefish, MT, USA, 1917; ISBN 978-1-4325-0694-0. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, C.P. The Practice of Osteopathy; Journal Printing Company: Highland, IL, USA, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Ching, L.M. The Still-Hildreth Sanatorium: A History and Chart Review. AAO J. 2014, 24, 12–25 and 34. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, E.W.A. Manual of Osteopathy: With the Application of Physical Culture, Baths, and Diet; Kessinger Publishing, LLC: Whitefish, MT, USA, 1900; ISBN 978-0344285110. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, J. Osteopathic Strap Technic; Forgotten Books: London, UK, 1919; ISBN 978-1-332-34667-7. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, T.B. Osteopathic Treatment in the Hypnotic State; CreateSpace: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 1899; ISBN 978-3337525293. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. Reflecting on New Models for Osteopathy—It’s Time for Change. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2019, 31, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanke, L.; Abbey, H. Developing a New Approach to Persistent Pain Management in Osteopathic Practice. Stage 1: A Feasibility Study for a Group Course. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 26, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, H.; Nanke, L.; Brownhill, K. Developing a Psychologically-Informed Pain Management Course for Use in Osteopathic Practice: The OsteoMAP Cohort Study. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021, 39, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, H. Communication Strategies in Psychologically Informed Osteopathic Practice: A Case Report. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2023, 47, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, T.; Neuhuber, W. Osteopathic Treatment Approach to Psychoemotional Trauma by Means of Bifocal Integration. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2020, 120, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleip, R.; Müller, D.G. Training Principles for Fascial Connective Tissues: Scientific Foundation and Suggested Practical Applications. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2013, 17, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofolini, A.; Svanera, D. Fascial Organisation of Motor Synergies: A Hypothesis. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2019, 29, 8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajimsha, M.S.; Shenoy, P.D.; Gampawar, N. Role of Fascial Connectivity in Musculoskeletal Dysfunctions: A Narrative Review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard, F.H.; Vleeming, A.; Schuenke, M.D.; Danneels, L.; Schleip, R. The Thoracolumbar Fascia: Anatomy, Function and Clinical Considerations. J. Anat. 2012, 221, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zügel, M.; Maganaris, C.N.; Wilke, J.; Jurkat-Rott, K.; Klingler, W.; Wearing, S.C.; Findley, T.; Barbe, M.F.; Steinacker, J.M.; Vleeming, A.; et al. Fascial Tissue Research in Sports Medicine: From Molecules to Tissue Adaptation, Injury and Diagnostics: Consensus Statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, J.; Krause, F.; Vogt, L.; Banzer, W. What Is Evidence-Based About Myofascial Chains: A Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.T.; Nair, K.; Evans, T.; Ghandour, Y. Clinical, Biomechanical, and Physiological Translational Interpretations of Human Resting Myofascial Tone or Tension. Int. J. Ther. Massage Bodyw. Res. Educ. Pract. 2010, 3, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.T.; Hannon, J.C. Human Resting Muscle Tone (HRMT): Narrative Introduction and Modern Concepts. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2008, 12, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.L.A.; Yu, Q.; Mao, Y.; Li, W.; Hu, C.; Li, L. Lumbar Muscles Biomechanical Characteristics in Young People with Chronic Spinal Pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lei, D.; Li, L.; Leng, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wei, X.; Lo, W.L.A. Quantifying Paraspinal Muscle Tone and Stiffness in Young Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Reliability Study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.; Masi, A.T.; Andonian, B.J.; Barry, A.J.; Coates, B.A.; Dougherty, J.; Schaefer, E.; Henderson, J.; Kelly, J. Stiffness of Resting Lumbar Myofascia in Healthy Young Subjects Quantified Using a Handheld Myotonometer and Concurrently with Surface Electromyography Monitoring. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2016, 20, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohlen, L.; Schwarze, J.; Richter, J.; Gietl, B.; Lazarov, C.; Kopyakova, A.; Brandl, A.; Schmidt, T. Effect of Osteopathic Techniques on Human Resting Muscle Tone in Healthy Subjects Using Myotonometry: A Factorial Randomized Trial. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Posta, D.; Branca, J.J.V.; Guarnieri, G.; Veltro, C.; Pacini, A.; Paternostro, F. Modularity of the Human Musculoskeletal System: The Correlation between Functional Structures by Computer Tools Analysis. Life 2022, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, S.Y.-C.; Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K. Focus of Attention and Its Impact on Movement Behaviour. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, J.E.; Cerritelli, F.; Kim, J.; Friston, K.J. Osteopathic Care as (En)Active Inference: A Theoretical Framework for Developing an Integrative Hypothesis in Osteopathy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stilwell, P.; Harman, K. An Enactive Approach to Pain: Beyond the Biopsychosocial Model. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2019, 18, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Abbey, H.; Casals-Gutiérrez, S.; Maretic, S. Reconceptualizing the Therapeutic Alliance in Osteopathic Practice: Integrating Insights from Phenomenology, Psychology and Enactive Inference. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2022, 46, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, C.; Consorti, G.; Turinetto, M.; Lunghi, C. Osteopathic Models Integration Radar Plot: A Proposed Framework for Osteopathic Diagnostic Clinical Reasoning. J. Chiropr. Humanit. 2021, 28, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, F.; Ruffini, N.; D’Alessandro, G.; Consorti, G.; Lunghi, C. The Role of Touch in Osteopathic Practice: A Narrative Review and Integrative Hypothesis. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 42, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A.J.; Langer, E.J. Mind-Set Matters: Exercise and the Placebo Effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepian, M.L.; Ambady, N. Fluid Movement and Creativity. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.; Franklin, E.; Stecco, C.; Schleip, R. Integrating Mental Imagery and Fascial Tissue: A Conceptualization for Research into Movement and Cognition. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 40, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Gibala, M.J.; Little, J.P. Exercise Snacks: A Novel Strategy to Improve Cardiometabolic Health. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2022, 50, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, T.W. Anatomy Trains. In Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists, Edinburgh, 3rd ed.; Churchill Livingstone Elsevier: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-7020-4654-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rhon, D.I.; Deyle, G.D. Manual Therapy: Always a Passive Treatment? J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickenbach, J.; Rubinelli, S.; Baffone, C.; Stucki, G. The Human Functioning Revolution: Implications for Health Systems and Sciences. Front. Sci. 2023, 1, 1118512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.A.; Stecco, C.; Stecco, A. Application of Fascial Manipulation© Technique in Chronic Shoulder Pain—Anatomical Basis and Clinical Implications. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2009, 13, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audoux, C.R.; Estrada-Barranco, C.; Martínez-Pozas, O.; Gozalo-Pascual, R.; Montaño-Ocaña, J.; García-Jiménez, D.; Vicente de Frutos, G.; Cabezas-Yagüe, E.; Sánchez Romero, E.A. What Concept of Manual Therapy Is More Effective to Improve Health Status in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome? A Study Protocol with Preliminary Results. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballestra, E.; Battaglino, A.; Cotella, D.; Rossettini, G.; Sanchez-Romero, E.A.; Villafane, J.H. Do patients’ expectations influence conservative treatment in Chronic Low Back Pain? A Narrative Review. Retos 2022, 46, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighenti, N.; Battaglino, A.; Sinatti, P.; Abuín-Porras, V.; Sánchez Romero, E.A.; Pedersini, P.; Villafañe, J.H. Effects of an Interdisciplinary Approach in the Management of Temporomandibular Disorders: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belluscio, V.; Bergamini, E.; Tramontano, M.; Formisano, R.; Buzzi, M.G.; Vannozzi, G. Does Curved Walking Sharpen the Assessment of Gait Disorders? An Instrumented Approach Based on Wearable Inertial Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M.; Manzari, L.; Bustos, A.S.O.; De Angelis, S.; Montemurro, R.; Belluscio, V.; Bergamini, E.; Vannozzi, G. Instrumental assessment of dynamic postural stability in patients with unilateral vestibular hypofunction during straight, curved, and blindfolded gait. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Neuroaesthetic enactive paradigm | The neuroaesthetic enactive paradigm has been proposed as a framework to describe the neuroaesthetic experiences that occur during osteopathic encounters. The neuroaesthetic enactive paradigm has been proposed as a framework to describe the neuroaesthetic experiences that occur during osteopathic encounters. The diagnostic process and the therapeutic intervention are meant to be verbal and nonverbal exchanges between the patient and the osteopath that will result in a pleasant surprise and a significant prediction error that will defy previous assumptions and update the brain’s generative model. The suggested shared sense decision-making method is based on closeness and nonverbal cues, notably touch, and can be strengthened by using verbal communication with a patient. To avoid nocebo effects and better promote the unique biological and psychological benefits of osteopathic touch, we hypothesize that sharing a pleasant feeling coming from a specifically selected form of executed touch (not another) in a patient’s body location (not another) can convey non-specific effects, such as placebo. |

| Predictive brain model | Predictive processing refers to any type of processing that incorporates or generates not only information about the past or the present but also about future states of the body or the environment. A positive surprise is evoked in the patient’s priors in the case of the osteopath–patient agreement on pleasant perception as a result of touching an area of interest for both agents, which leads to re-designing predictive models more in line with the ecological–social context in which the patient lives. |

| Ecological niche in osteopath–patient encounter | An ecological niche is a biopsychosocial context in which there occur interactions between individuals in the ecosystem. The osteopath–patient dyad provides a body–mind state alignment and participates in building an ecological niche in which osteopathic care occurs. The relationship between the osteopath and the patient fills an ecological niche by providing both parties with opportunities to support the patient’s adaptability and ability to reclaim control over their everyday activities, improving their health and well-being. |

| Therapeutic alliance in osteopathic care | The collaborative relationship between the patient and the healthcare professional, known as a therapeutic alliance, entails a connection between the two individuals as well as a shared awareness of the objectives of treatment and the range of therapeutic tasks and interventions. A combination of effective therapeutic alliance and musculoskeletal approaches (such as osteopathic care) could influence patients’ functions and agency, resulting in the adaptation and restoration of new body narratives and predictive models. |

| Assessment | Multidimensional aspects of patient health (ability to carry out daily activities, familiar symptoms, comparative signs, functional objective examination, and symptom-based objective examination); FNA; Palpatory findings; Emergent patient pattern occurring from a shared decision-making process achieved with a neuroaesthetic enactive dyadic (osteopathic/patient) multi-perceptive experience. |

| Osteopathic manipulative treatment | Personalized manipulative treatment based on the patient’s emergent pattern occurring from a shared decision-making process achieved with a neuroaesthetic enactive dyadic (osteopathic/patient) multi-perceptive experience. |

| PAOAs | The practitioner implements verbal educative content with metaphors, graphical outlines, and visual representations to improve, via gamification, patient self-care knowledge about exercise, ergonomics, and dietary and lifestyle strategies. Personalized exercise based on the patient’s emergent pattern occurring from a shared decision-making process is achieved with a neuroaesthetic enactive dyadic (osteopathic/patient) multi-perceptive experience; for example, FNA can be promoted as assisted exercise. |

| Re-assessment | Multidimensional aspects of patient health (ability to carry out daily activities, familiar symptoms, and comparative signs, functional objective examination, and symptom-based objective examination); FNA; Palpatory findings; Emergent patient pattern occurring from a shared decision-making process achieved with a neuroaesthetic enactive dyadic (osteopathic/patient) multi-perceptive experience. |

| Type of Study | Aim |

|---|---|

| Delphi panel and consensus workshop with grounded theory | To generate a sharable outline of an interprofessional model; To develop FNA models adapted for fragile populations and subjects with more delicate physical conditions. |

| Validity studies | To evaluate face, content, and construct validity, as well as the reliability and predictive capacity of the FNA in clinical practice to define its clinical usefulness. |

| Observational studies | To assess patient-reported outcomes, clinical outcomes, and patient satisfaction between subjects treated with integrated passive and active strategies rather than an exclusively passive approach; To evaluate the impact of active–participative approaches on motivation levels and goals for physical exercise; To evaluate the impact of active–participative approaches on quality of life, patient-reported outcomes, and patient-reported experience. |

| Randomized control trials | To research the effectiveness of exposure to FNA-based exercise as active inference; To evaluate the clinical implications of manual therapy with interdisciplinary and combined practice. |

| Mentorship, continuing professional development, and consensus workshop | To better contextualize the framework in the approaches promoted by different professionals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baroni, F.; Schleip, R.; Arcuri, L.; Consorti, G.; D’Alessandro, G.; Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Vitali, A.M.; Tramontano, M.; Lunghi, C. Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Interprofessional Assessment to Inform Person-Centered Participative Care—An Osteopathic Perspective. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212886

Baroni F, Schleip R, Arcuri L, Consorti G, D’Alessandro G, Zegarra-Parodi R, Vitali AM, Tramontano M, Lunghi C. Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Interprofessional Assessment to Inform Person-Centered Participative Care—An Osteopathic Perspective. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212886

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaroni, Francesca, Robert Schleip, Lorenzo Arcuri, Giacomo Consorti, Giandomenico D’Alessandro, Rafael Zegarra-Parodi, Anna Maria Vitali, Marco Tramontano, and Christian Lunghi. 2023. "Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Interprofessional Assessment to Inform Person-Centered Participative Care—An Osteopathic Perspective" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212886

APA StyleBaroni, F., Schleip, R., Arcuri, L., Consorti, G., D’Alessandro, G., Zegarra-Parodi, R., Vitali, A. M., Tramontano, M., & Lunghi, C. (2023). Functional Neuromyofascial Activity: Interprofessional Assessment to Inform Person-Centered Participative Care—An Osteopathic Perspective. Healthcare, 11(21), 2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212886