Comparative Analysis of Patient Satisfaction Surveys—A Crucial Role in Raising the Standard of Healthcare Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

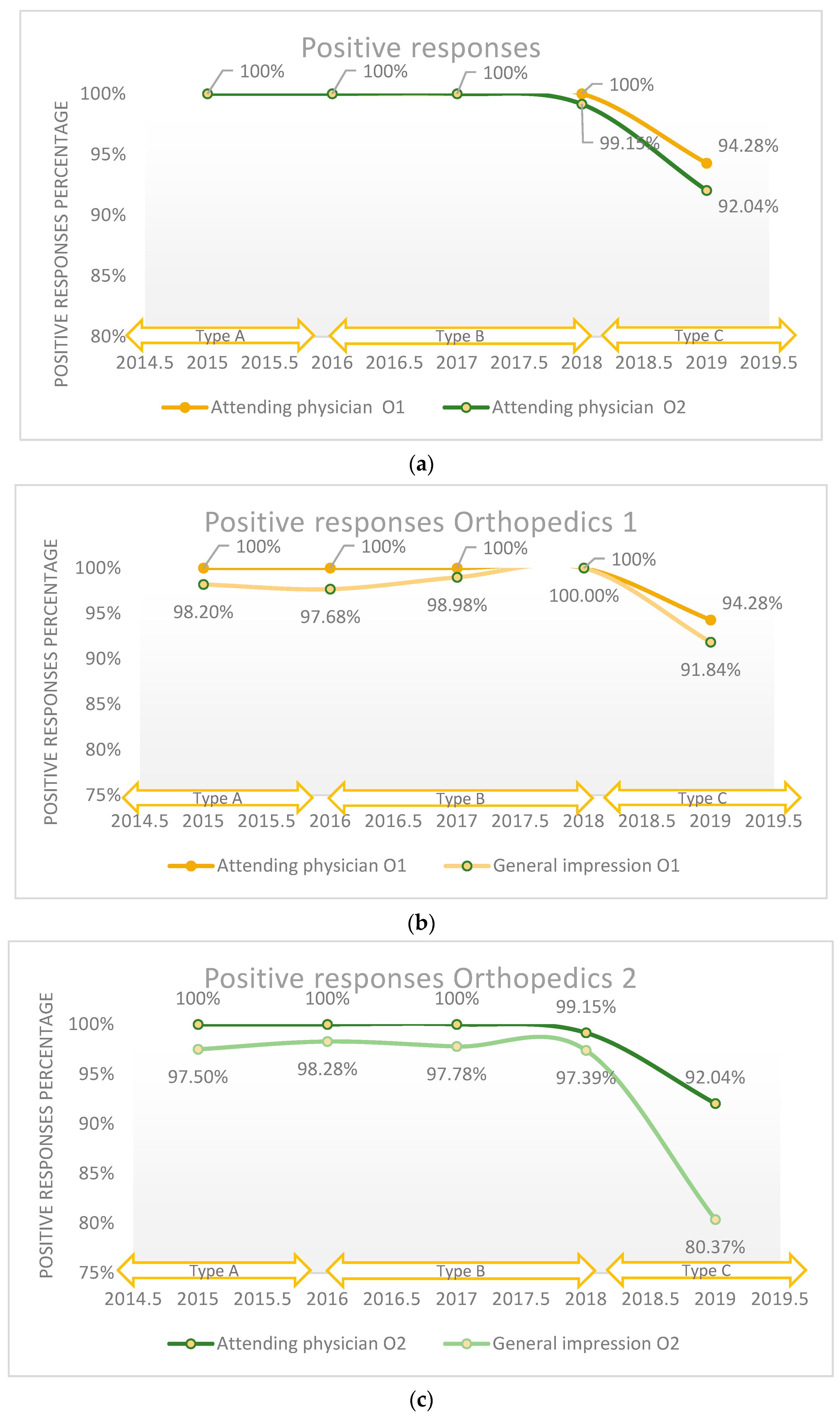

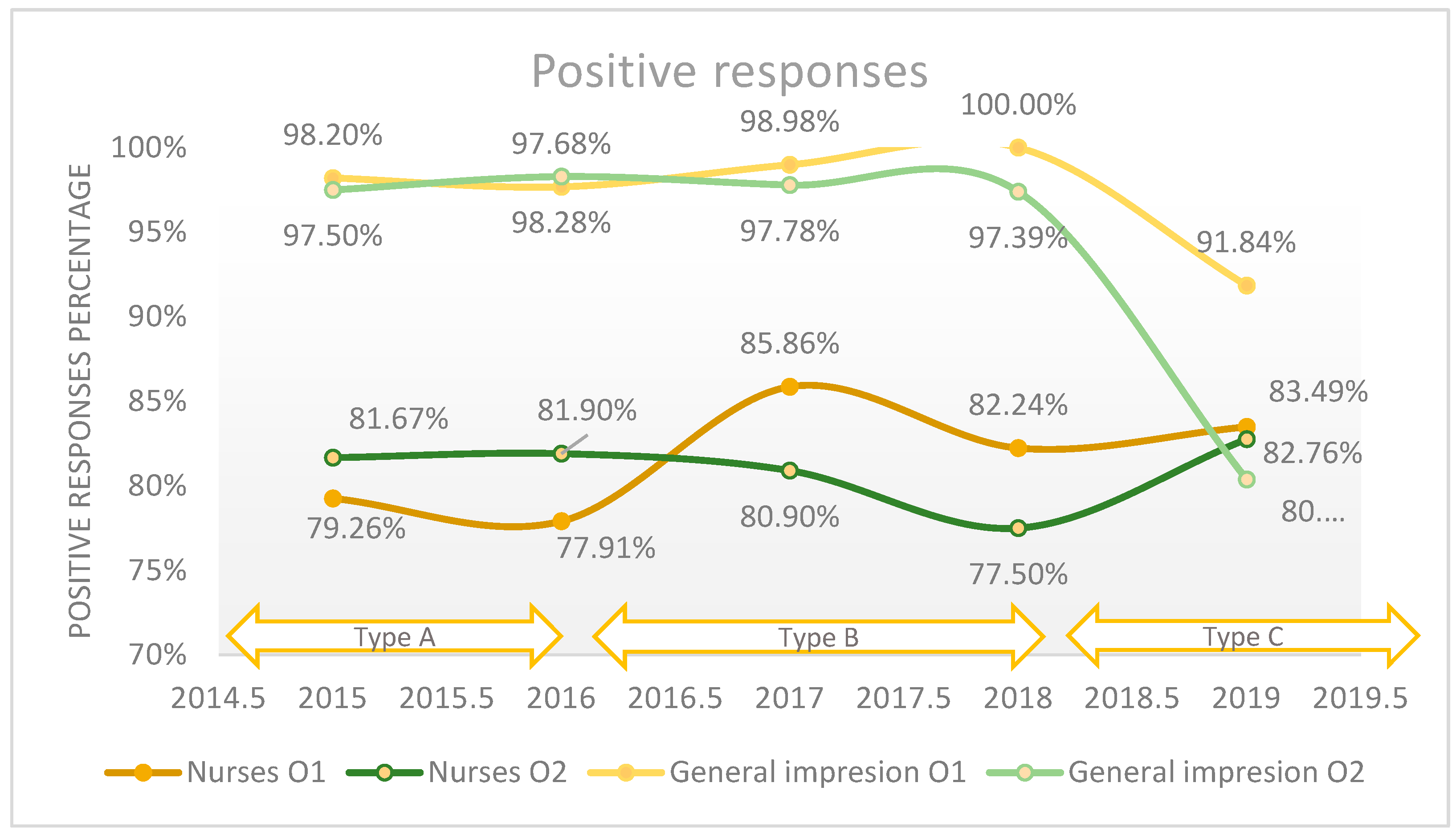

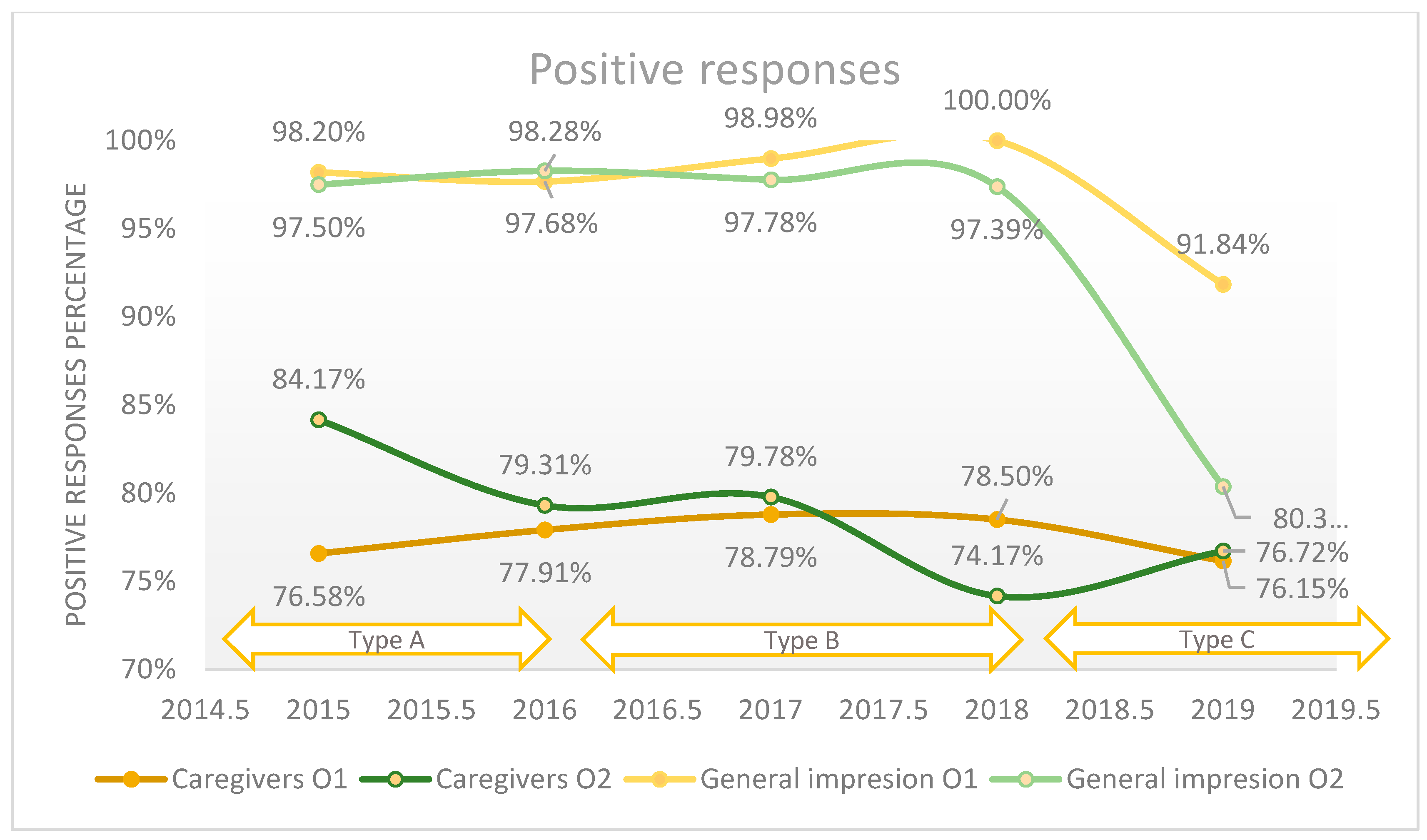

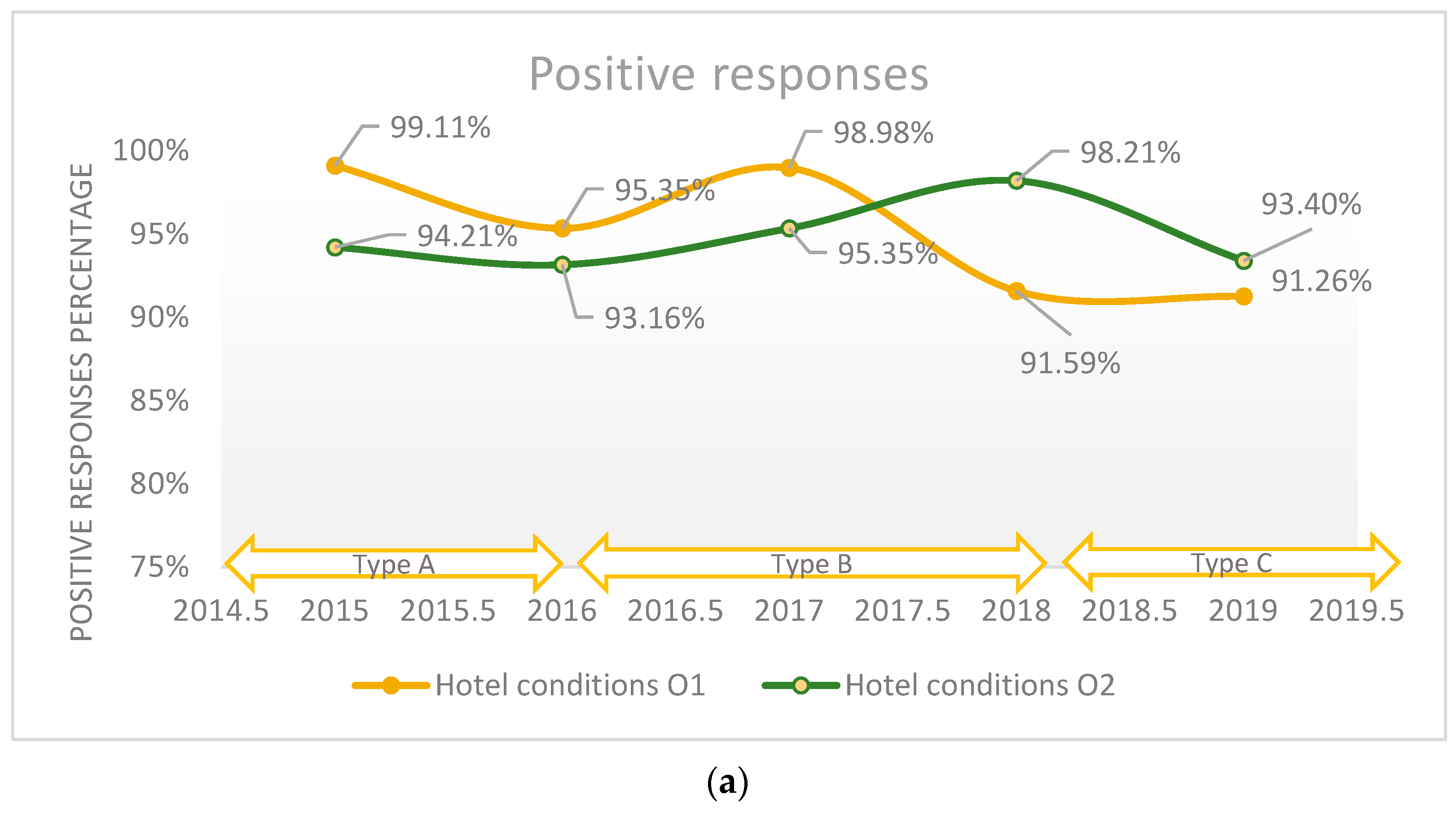

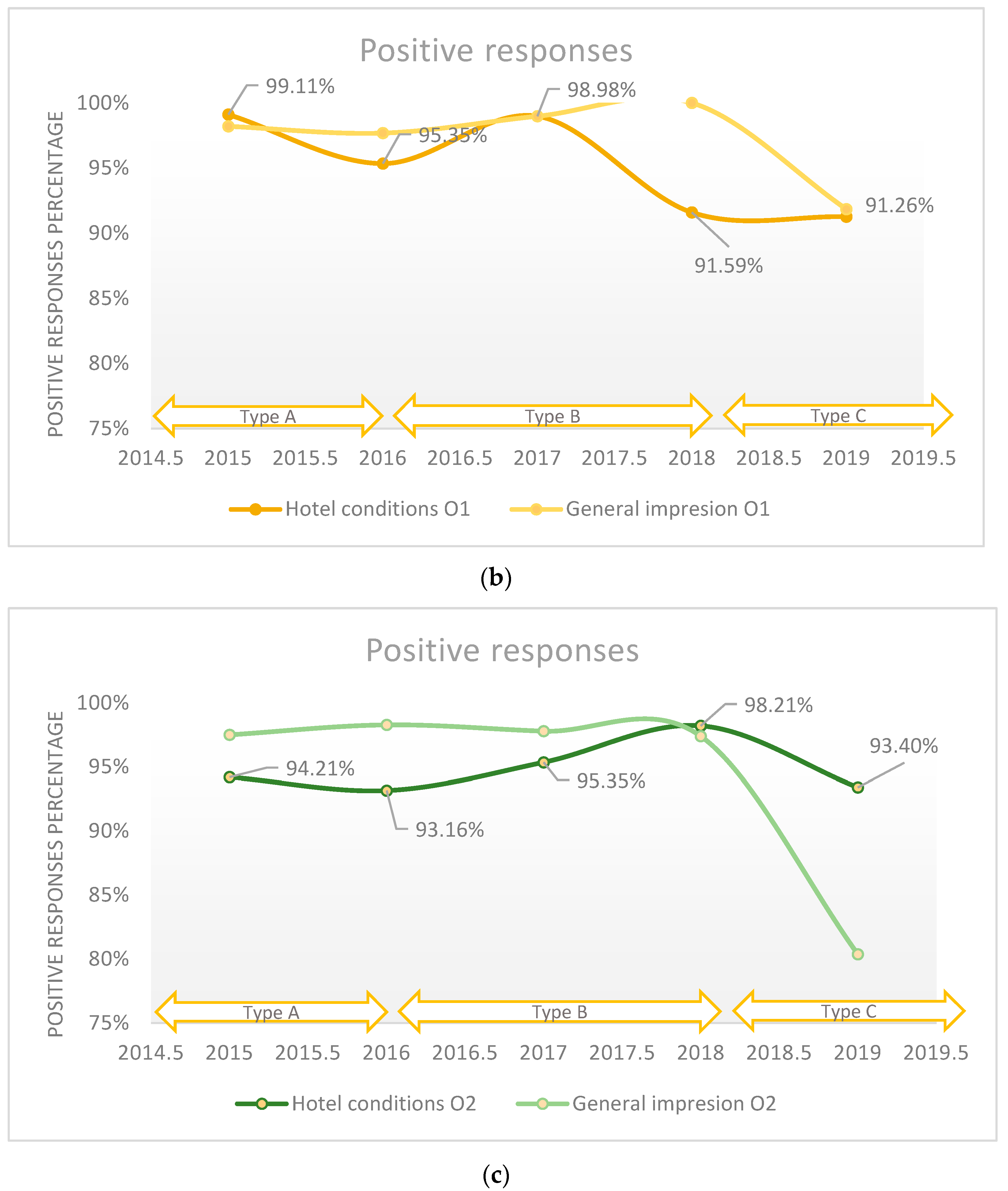

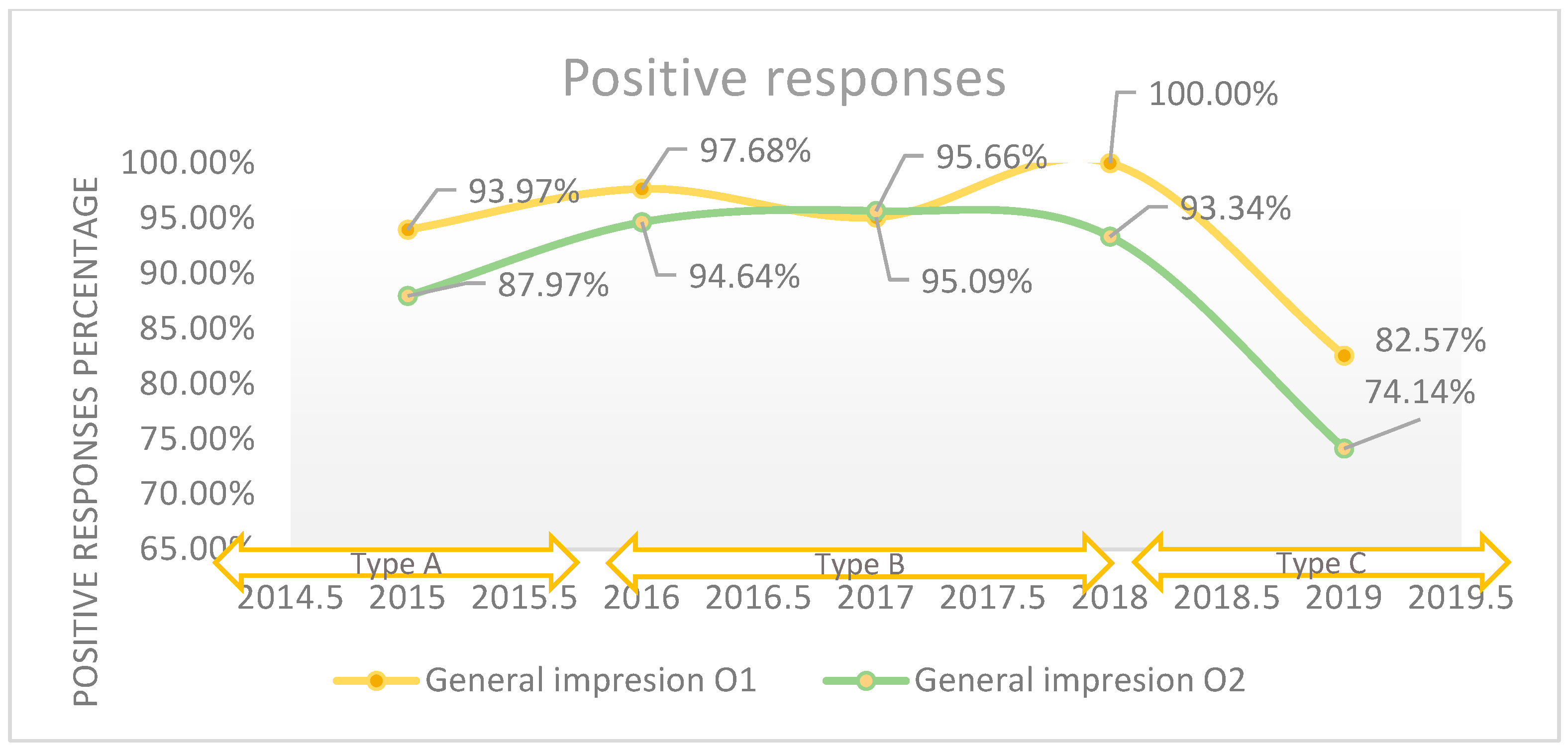

- Comparative analysis of the variants of satisfaction questionnaires applied in the studied period. Identifying an optimal rating scale by benchmarking patient satisfaction questionnaires and evaluation of the quality perceived by the patient regarding the care provided by the medical staff, hotel services, and the general impression of the hospital.

- Evaluation of the patient’s overall opinion (general impression) in relation to the quality of medical care provided by the hospital staff and hotel conditions in the hospital.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection and Tools

- Q15A, Q15B: Are you satisfied with the hotel conditions (accommodation)?□ Very satisfied □ Satisfied □ Unsatisfied

- Q14C: Are you satisfied with the accommodation conditions—salon (equipment, facilities)?□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer

- Q17A, Q18B: The quality of medical care provided by:Your doctor: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very goodNurses: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very goodCaregivers: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very good

- Q15C: The quality of medical care provided by (1—unsatisfactory.... 5—very good):Your doctor: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answerNurses: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answerCaregivers: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer

- Q29A, Q30B: Your general impression of the hospital?□ Very satisfied □ Satisfied □ Unsatisfied

- Q36C: Your general impression of the hospital?□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Participants

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies. 2010. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Ministry of Health. Order no. 1.501/2016 regarding the approval of the implementation of the patient feedback mechanism in public hospitals. Official Gazette, 9 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Order no. 446/2017, regarding the approval of Standards, Procedures and methodology for evaluation and accreditation of hospitals. Official Gazette, 27 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Strategy for Quality Assurance in the Health System, for the Period 2018–2025. Available online: https://anmcs.gov.ro (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Xesfingi, S.; Vozikis, A. Patient satisfaction with the healthcare system: Assessing the impact of socio-economic and healthcare provision factors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voda, A.I.; Bostan, I.; Tiganas, C.G. Impact of Macroeconomic and Healthcare Provision Factors on Patient Satisfaction. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armean, P. Quality Management of Health Services; Coresi Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- The Romania Government Decision No. 1028 of 18 November 2014 Regarding the Approval of the National Health Strategy 2014–2020 and the Action Plan for the Period 2014–2020 for the Implementation of the National Strategy. Official Gazette, 8 December 2014.

- Murillo, C.; Saurina, C. Measurement of the importance of user satisfaction dimensions in healthcare provision. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamra, V.; Singh, H.; De, K.K. Factors affecting patient satisfaction: An exploratory study for quality management in the health-care sector. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2015, 27, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, P.; Prodan, A.; Duşe, D.M.; Duşe, C.S.; Lefter, V.; Mãlãescu, S.; Moraru, C.; Porumb, E.M.; Puia, R.Ş. Human Resource Management; Online Edition; UEFISCDI: Bucharest, Romania, 2011; ISBN 978-973-0-11686-1. [Google Scholar]

- Taqdees, F.; Shahab, A.; Asma, S. Hospital healthcare service quality, patient satisfaction and loyalty. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 1194–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Maesala, A.; Paul, J. Service quality, consumer satisfaction and loyalty in hospitals: Thinking for the future. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National School of Public Health and Health Management, Hospital Management; Public H Press: Bucharest, Romania, 2006.

- Kruk, M.E.; Kelley, E.; Syed, S.B.; Tarp, F.; Addison, T.; Akachi, Y. Measuring quality of health-care services: What is known and where are the gaps? Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinyiza, F.W.; Kaseka, P.U.; Chisale, M.R.O.; Chimbatata, C.S.; Mbakaya, B.C.; Kamudumuli, P.S.; Wu, T.J.; Kayira, A.B. Patient satisfaction with health care at a tertiary hospital in Northern Malawi: Results from a triangulated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. The Quality of Care: How Can It Be Assessed? JAMA 1988, 260, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J. Patient-centred care as an approach to improving health care in Australia. Collegian 2018, 25, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhang, P.R.; Elliott, M.N.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Hays, R.D.; Lerhmann, W.G.; Ribowsky, L.; Edgman-Levitan, S.; Cleary, P.D. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2014, 71, 522–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, L.G.; Sabău, M.; Daina, C.M.; Neamțu, C.; Buhaș, C.L.; Bungau, C.; Aleya, L.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M. Improving perfor-mance of a pharmacy in a Romanian hospital through implementation of an internal management control system. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 675, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batbaatar, E.; Dorjdagva, J.; Luvsannyam, A.; Savino, M.M.; Amenta, P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A systematic review. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, G.D.; Tevis, S.E.; Kent, K.C. Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Ann. Surg. 2014, 1, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.; Abdalkarim, S.; Mohammed, M.W.; Yahya Ali, G.; Mohammed Ahmed, M.; Youns Khan, M.; Mousa Faqeeh, H.; Ali Ahmed Alhazmi, A.; Hamad Ahmad, O.; Ali Jubran, R.; et al. Patient Satisfaction and Its Predictors in the General Hospitals of Southwest Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Sudan. JMS 2022, 17, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremwork Contract for 2021–2022 and the Norms of Application. Available online: https://www.casan.ro/castl/post/type/local/contractului-cadru-pentru-2021-2022-si-normele-de-aplicare.html (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Chen, L.M.; Birkmeyer, J.D.; Saint, S.; Jha, A.K. Hospitalist staffing and patient satisfaction in the national medicare population. J. Hosp. Med. 2013, 8, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torok, H.; Ghazarian, S.R.; Kotwal, S.; Landis, R.; Wright, S.; Howell, E. Development and validation of the tool to assess in-patient satisfaction with care from hospitalists. J. Hosp. Med. 2014, 9, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesluk, B.J.; Bernabeo, E.; Hess, B.; Lynn, L.A.; Reddy, S.; Holmboe, E.S. A new tool to give hospitalists feedback to improve interprofessional teamwork and advance patient care. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 2485–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chae, W.; Kim, J.; Park, E.-C.; Jang, S.-I. Comparison of Patient Satisfaction in Inpatient Care Provided by Hospitalists and Nonhospitalists in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, G.Z.; Munteanu, Z.V.I.; Roiu, G.; Daina, C.M.; Moraru, R.; Moraru, L.; Trambitas, C.; Badau, D.; Daina, L.G. Aspects of Tertiary Prevention in Patients with Primary Open Angle Glaucoma. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanefeld, J.; Powell-Jackson, T.; Balabanova, D. Understanding and measuring quality of care: Dealing with complexity. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 5, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzelepis, F.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W.; Zucca, A.C.; Fradgley, E.A. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: Why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 9, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N.; Kanwel, S. Promoting OPD Patient Satisfaction through Different Healthcare Determinants: A Study of Public Sector Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janto, M.; Iurcov, R.; Daina, C.M.; Neculoiu, D.C.; Venter, A.C.; Badau, D.; Cotovanu, A.; Negrau, M.; Suteu, C.L.; Sabau, M.; et al. Oral health among elderly, impact on life quality, access of elderly patients to oral health services and methods to im-prove oral health: A narrative review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjertnæs, Ø.A.; Iversen, H.H.; Valderas, J.M. Patient experiences with general practitioners: Psychometric performance of the generic PEQ-GP instrument among patients with chronic conditions. Fam. Pract. 2021, 39, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, C.; Patel, S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Fukuhara, S.; Yamamoto, Y. Development and validation of a concise scale for assessing patient experience of primary care for adults in Japan. Fam. Pract. 2020, 37, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.L.; Raposo, V.; Tavares, A.I. Primary health care patient satisfaction: Explanatory factors and geographic characteristics. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2020, 32, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derriennic, J.; Nabbe, P.; Barais, M.; Le Goff, D.; Pourtau, T.; Penpennic, B.; Le Reste, J.-Y. A systematic literature review of patient self-assessment instruments concerning quality of primary care in multiprofessional clinics. Fam. Pract. 2022, 5, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.D.; Vu, S.T.; Pham, Y.T.K.; Vu, N.T. Evaluating performance of Vietnamese Public Hospitals Based on Balanced Scorecard. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabash, M.I.; Albugami, M.A.; Salim, M.; Akhtar, A. Service quality dimensions of e-retailing of Islamic banks and its impact on customer satisfaction: An empirical investigation of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Malik, S.A.; Malik, S.A. Measuring patients’ healthcare service quality perceptions, satisfaction, and loyalty in public and private sector hospitals in Pakistan. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2016, 33, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.D. Assessing the effects of service quality, experience value, relationship quality on behavioral intentions. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.O.; Kagle, J.D. Understanding Patient Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with Health Care. Health Soc. Work. 1991, 16, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Shah, S.I.A. Patient Satisfaction with Health Care Services; An Application of Phy-sician’s Behavior as a Moderator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Ball, J.; Bruyneel, L.; Rafferty, A.M.; Griffiths, P. Patient satisfaction with hospital care and nurses in England: An observational study. BMJ Open 2017, 8, e019189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamrew, N.; Endris, A.A.; Tadesse, M. Level of Patient Satisfaction with Inpatient Services and Its Determinants: A Study of a Specialized Hospital in Ethiopia. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 2473469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.M.; Duong, T.T.L. The Relationship between Hospital Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: An Empirical Study from Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Ward, P.; Mohammadnezhad, M. Factors Associated with Patient Satisfaction in Outpatient Department of Suva Sub-divisional Health Center, Fiji, 2018: A Mixed Method Study. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Dvorsky, J.; Popesko, B. Patient Satisfaction Determinants of Inpatient Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, S.M.; Raeissi, P.; Nasiripour, A.A.; Tabibi, S.J. Factors affecting the quality of hospital hotel services from the patients and their companions’ point of view: A national study in Iran. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2016, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Awadh, M. Utilizing Multi-Criteria Decision Making to Evaluate the Quality of Healthcare Services. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.I.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Musa, K.I.; Chua, S.-L.; Yaacob, N.M. Assessing Patient-Perceived Hospital Service Quality and Sentiment in Malaysian Public Hospitals Using Machine Learning and Facebook Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls Martínez, M.d.C.; Ramírez-Orellana, A.; Grasso, M.S. Health Investment Management and Healthcare Quality in the Public System: A Gender Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duc Thanh, N.; My Anh, B.T.; Xiem, C.H.; Quynh Anh, P.; Tien, P.H.; Thi Phuong Thanh, N.; Huu Quang, C.; Ha, V.T.; Thanh Hung, P. Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Service Quality and Its Associated Factors at One Polyclinic in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1605055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, J.M.S.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Lizarelli, F.L.; Roscani, M.G. Instruments to measure patient experience in hospitals: A scoping review. Gestão Produção 2022, 29, e0821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Observatory. Health Systems and Policies. In Romania: Country Health Profile 2021; State of Health in the EU; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–24. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/countries/romania/romania-country-health-profile-2021-74ad9999-en.htm (accessed on 14 October 2022).

| Section/ Domain | No. | Question | Questionnaire | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||

| No. of Questions | 30 | 31 | 37 | ||

| Demographic data | Q1 | You are: □ female □ male | X | X | X * |

| Q2 | Residence: □ rural □ urban | X | X | X * | |

| Q3 | Your age: ........years old | X | X | X * | |

| Q4 | Education: □ Higher education □ High school diploma □ 8th class/grade □ 4th class/grade | X | X | X * | |

| Admission | Q5A, Q5B | You were admitted to the ward of................................... | X | X | - |

| Q6A, Q6B | Upon admission, you were accompanied, from the Admissions Office to ward, by: □ Health personnel □ Family/friends □ I was not accompanied by anyone | X | X | - | |

| Q7A, Q7B | If you have been hospitalized through the Emergency department, the attitude of the staff at the Emergency Reception Room: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very good | X | X | - | |

| Q8A, Q8B | Specify the time elapsed from admission (through the Admissions Office—not through Emergency) until you arrived at the salon: □ Less than an hour □ An hour □ In 2 h □ In 3 h □ Over 3 h | X | X | - | |

| Q9A, Q9B | Give a mark (from 1 to 5) to the guard staff who dealt with you (please circle the corresponding number, 1—unsatisfactory....5—very good). □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □5 | X | X | - | |

| Q10A, Q10B | ** Have you been admitted to this hospital before? □ Yes □ No If the answer is YES, you returned to this hospital because: □ The medical staff is kind □ I was referred by the family doctor or specialist □ It is close to my home (it is within reach) □ I have no other options | X | X | - | |

| Q5C | How you came to be admitted to our hospital: □ You presented yourself directly to the Emergency department□ You had a referral from your family doctor □ You had a referral from the outpatient doctor □ You came by ambulance □ Other situation □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q6C | From the Admissions Office to the salon, were you accompanied by medical personnel? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q7C | Were you accompanied by family members from the Admissions Office to the salon? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q8C | ** Have you been admitted to this hospital before? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q9C | If you needed a medical service, would you return here? (1—certainly no...5-certainly yes) □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Hotel conditions | Q11A, Q11B | The food in the hospital is: □ Good □ Very good □ Not tasty □ Too little | X | X | - |

| Q12A, Q12B | You received the food on time: □ Yes □ No □ I do not know | X | X | - | |

| Q13A, Q13B | ** Specify how many times a day your salon/room is cleaned: □ Once a day □ 2 times a day □ 3 times a day □ Several times a day | X | X | - | |

| Q14A, Q14B | ** The cleanliness of your salon is: □ Non-existent □ Good □ Very good | X | X | - | |

| Q15A, Q15B | ** Are you satisfied with the hotel conditions (accommodation)? □ Very satisfied □ Satisfied □ Unsatisfied | X | X | - | |

| Q16B | What do you think about the quality of the linen? □ Non-existent □ Good □ Very good | - | X | - | |

| Q10C | The quality of food in the hospital is: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q11C | What do you think about the quality of sanitary groups? □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q12C | ** Specify how many times a day your salon/room is cleaned: □ Once a day □ 2 times a day □ As many times as necessary □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q13C | ** The cleanliness of your salon is: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q14C | ** Are you satisfied with the accommodation conditions—salon (equipment, facilities)? □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Quality of medical care | Q16A, Q17B | The time allotted by the salon doctor for your consultation: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very good | X | X | - |

| Q17A, Q18B | ** The quality of medical care provided by: Your doctor: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very good Nurses: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very good Caregivers: □ Unsatisfactory □ Good □ Very good | X | X | - | |

| Q18A, Q19B | Were you satisfied with the care provided? During the day: □ Yes □ No During the night: □ Yes □ No Saturday, Sunday, and public holidays: □ Yes □ No | X | X | - | |

| Q19A, Q20B | How do you rate the contact with the hospital staff? □ Agreeable □ Cold/impersonal □ Warm/close □ Unpleasant | X | X | - | |

| Q15C | ** The quality of medical care provided by: Your doctor: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer Nurses: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer Caregivers: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer (1—unsatisfactory....5—very good) | - | - | X | |

| Q16C | How do you rate the attitude of the hospital staff? (1—unsatisfactory....5—very good) □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q17C | Did you have surgery during your hospitalization? □ Yes □ No | - | - | X | |

| Q18C | How do you rate the post-operative care and medical care provided in the Intensive Care Unit (if applicable)? □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ Not applicable/no answer | - | - | X | |

| Q19C | Were you satisfied with the spiritual care in the hospital? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Patient’s safety and rights | Q20A, Q21B | ** During the hospitalization you bought medicines: □ Yes □ No | X | X | - |

| Q21A, Q22B | ** Can you name a medicine that was administered to you in the hospital? □ Yes □ No □ Specify the name of the medicine………………………….. | X | X | - | |

| Q22A, Q23B | Do you know at least one adverse effect of the administered drug or risk of the procedure performed? □ Yes □ No □ Specify..................................................... | X | X | - | |

| Q23A, Q24B | Was the administration of oral medications (tablets) done by the nurse? □ Yes, always □ Yes, sometimes □ No, never | X | X | - | |

| Q24A, Q25B | From whom did you learn your diagnosis (disease)? □ The hospital doctor □ Salon assistant □ I do not know my diagnosis | X | X | - | |

| Q25A, Q26B | Do you know what kind of tests were done in the hospital? □ Yes □ No □ I was not tested | X | X | - | |

| Q26A, Q27B | ** Have you been informed about your rights in the hospital? □ Yes, at the admission office □ Yes, only verbally □ No | X | X | - | |

| Q27A, Q28B | Did you have surgery during your hospitalization? □ Yes □ No Have you talked to your doctor about the surgery you had and its risks? □ Yes, everything was explained to me step by step □ I did not receive any explanation | X | X | - | |

| Q28A, Q29B | ** Is the visiting schedule observed on the ward where you were admitted? □ Yes □ No | X | X | - | |

| Q20C | Were you accompanied by designated staff when moving around the hospital (for explorations)? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q21C | Do you know the identity of the medical personnel involved in providing medical services? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q22C | ** During the hospitalization, you bought medicines? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q23C | ** Can you name a medicine that was administered to you in the hospital? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q24C | Have you been informed about the adverse effects of the drugs administered in the hospital? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q25C | Have the vials administered been opened in front of you? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q26C | Do medical personnel use disposable gloves in every contact with you? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q27C | ** Have you been informed about your rights and obligations in the hospital? □ Yes, at the admission office □ Yes, only verbally □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q28C | Have you been informed about the way to submit suggestions and complaints? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q29C | Have you been informed of the estimated date of discharge? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q30C | Have you been informed about the risk of falling? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q31C | Were you informed about your diagnosis? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q32C | Did you receive information about how the disease/illness will evolve and the therapeutic plan followed? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q33C | During your hospitalization, did you reward any medical staff (doctor, assistant, nurse, carer, stretcher bearer, etc.) with money or gifts? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Q34C | If the answer was YES to the previous question, please specify the professional category of the medical staff: □ Doctor □ Caregivers □ Others □ Nurse □ Stretcher bearer □ Not applicable/no answer | - | - | X | |

| Q35C | ** Is the visiting schedule observed on the ward where you were admitted? □ Yes □ No □ Do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Overall satisfaction | Q29A, Q30B | Your general impression of the hospital? □ Very satisfied □ Satisfied □ Unsatisfied | X | X | - |

| Q36C | Your general impression of the hospital? □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ I do not answer | - | - | X | |

| Observations/suggestions | Q30A, Q31B, Q37C | X | X | X | |

| Characteristic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | Type A | Type B | Type C |

| Period | 2015–2016 | 2017–2018 | 2019 |

| No. of questions | 30 | 31 | 37 |

| Quality assessment with Likert scale | Three-point scale and five-point scale | Five-point scale | |

| (3–5 values) | (5 values) | ||

| Correspondence of scales | Very good -> 5–4 | 5—Very good | |

| 4—Medium good | |||

| Good -> 3 | 3—Good | ||

| 2—Satisfactory | |||

| Unsatisfactory -> 1–2 | 1—Unsatisfactory | ||

| Characteristic | N (%) | p-Value * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Orthopedics 1 (O1) | Orthopedics 2 (O2) | Total subjects | |

| Study sample | 520 (47.2%) | 581 (52.8%) | 1101 (100%) | |

| Sex | 0.042 | |||

| Male | 231 (44.4%) | 295 (50.7%) | 522 (47.8%) | |

| Female | 289 (55.6%) | 286 (49.2%) | 575 (52.2%) | |

| Residence | 0.030 | |||

| Urban | 238 (45.8%) | 286 (49.2%) | 445 (45.93%) | |

| Rural | 228 (43.98%) | 217 (37.4%) | 524 (54.07%) | |

| Declined to answer | 54 (10.4%) | 78 (13.4%) | 132 (11.98%) | |

| Education | 0.046 | |||

| Higher education | 204 (39.2%) | 205 (35.3%) | 409 (38.26%) | |

| High school diploma | 99 (19%) | 95 (16.4%) | 194 (18.14%) | |

| 8th class/grade | 156 (30%) | 201 (34.6%) | 357 (33.40%) | |

| 4th class/grade | 46 (8.8%) | 63 (10.8%) | 109 (10.20%) | |

| Declined to answer | 15 (2.9%) | 17 (2.9%) | 32 (2.91%) | |

| Questionaire | Type A | Type B | Type C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha value * | 0.596197 | 0.246734 | 0.706937 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bancsik, K.; Ilea, C.D.N.; Daina, M.D.; Bancsik, R.; Șuteu, C.L.; Bîrsan, S.D.; Manole, F.; Daina, L.G. Comparative Analysis of Patient Satisfaction Surveys—A Crucial Role in Raising the Standard of Healthcare Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212878

Bancsik K, Ilea CDN, Daina MD, Bancsik R, Șuteu CL, Bîrsan SD, Manole F, Daina LG. Comparative Analysis of Patient Satisfaction Surveys—A Crucial Role in Raising the Standard of Healthcare Services. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212878

Chicago/Turabian StyleBancsik, Karoly, Codrin Dan Nicolae Ilea, Mădălina Diana Daina, Raluca Bancsik, Corina Lacramioara Șuteu, Simona Daciana Bîrsan, Felicia Manole, and Lucia Georgeta Daina. 2023. "Comparative Analysis of Patient Satisfaction Surveys—A Crucial Role in Raising the Standard of Healthcare Services" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212878

APA StyleBancsik, K., Ilea, C. D. N., Daina, M. D., Bancsik, R., Șuteu, C. L., Bîrsan, S. D., Manole, F., & Daina, L. G. (2023). Comparative Analysis of Patient Satisfaction Surveys—A Crucial Role in Raising the Standard of Healthcare Services. Healthcare, 11(21), 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212878