Sexuality in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

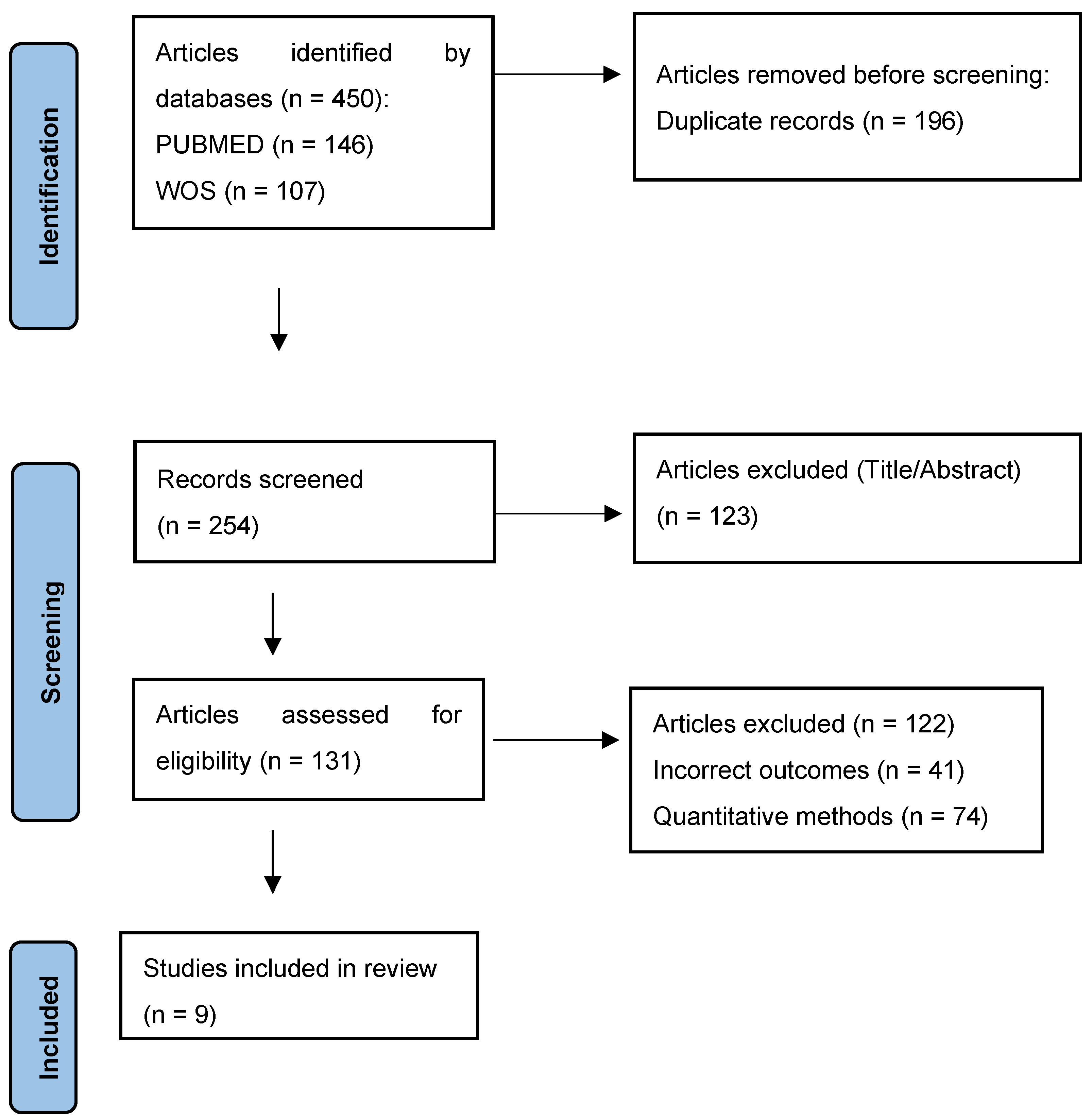

2.2. Search Methods

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Search Results

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.8. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. “I Want to, but I Can’t”: A Shift in Feminine Sexuality

3.1.1. Pain/Stiffness Limit Pleasure and Desire

The pain is concentrated in the vaginal area, the moment of penetration is really painful for both partners. We didn’t have these problems before, it was all because I was diagnosed with FMS.[34]

Sometimes you have to say, ‘Stop, stop, … you’re hurting me, I can’t do it’. Or he holds you and … ‘Ow, you’re hurting me![24]

Changing positions during our encounters hurts a lot; I didn’t have this problem before, now it hurts anytime we do anything out of the ordinary…[35]

3.1.2. Irritability and Low Mood

When I am in such intense pain, I get a bad temper and tell him to leave me alone, that I do not want to be with anyone, nor with myself. By the pain I get bad and insult him without him deserving it.[35]

I had a lot of discomfort doing it (coitus), some pain here (vulva) and I didn’t have one (an orgasm). I was very nervous, I couldn’t relax, I wasn’t enjoying it. How can you always explain that? It’s like… it’s a bit ridiculous.[24]

Get up every day and hear that it is hurting me here or there, I know it must be exhausting. It is enough that I must deal with this daily to make another person deal with the same thing … I know it’s difficult and that’s why I always try to show a good face and avoid him knowing that it hurts me.[35]

3.1.3. Decreased Frequency/Difficulty Reaching Orgasm

My mood is directly related to the amount of pain I’m in. My irritability is directly related to the amount of pain I’m in… so, if I’m in a bad mood, feeling irritable and in pain, I’m not going to want to have sex.[36]

Before I had the disease, when I was 35 years old, we were able to have sex once or twice a week. Since I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia about five years ago, the frequency has dropped to about once every two months.[39]

3.1.4. Pharmacological Treatment Does Not Help Sexuality

Took it, but the muscular weakness was so bad in my legs that I couldn’t get up… I told them that I wouldn’t take Tramadol® anymore or any other drug. They told me, “Well then, next time you can go to mental health.[9]

3.1.5. Having Sex “for Your Partner”: Avoiding Encounters

It’s not that I say I don’t want to, I just do everything in my power to make sure the situation doesn’t arise (…) from the afternoon on, I start telling my husband that I feel really badly and that way I can ensure that nothing sexual is going to happen between us that night.[34]

When my husband initiates sex with me (I never do), the first thing that comes to my mind is that I will have pain in my legs and hips for more than a week because of the movements and postures. This takes away all my urges, even though I might have some desire to make love. If I see that my husband is very eager, then I’ll give him that reward because the poor guy is very good to me and he deserves it.[39]

I do it for my husband. Yes, it’s for him, because I don’t feel like having sex at all.[36]

3.2. Resetting Sex Life and Intimacy

3.2.1. I Know it’s Not Mutual

I feel terrible for not being able to be more affectionate … but I know that this is because of the pain, because of the anguish I feel all the time.[35]

He (my partner) knows that I don’t do it because I feel like it, but to satisfy him, obviously. There are times when he finishes (orgasm) and you,…mmm,… you don’t, and he also feels guilty and frustrated.[24]

3.2.2. Bearing the Moral Burden

He [my husband] takes care of me, I am the wife, so it is right for the man to take care of the woman […] the woman takes care of the man with the housework, washing, ironing, tidying, giving [sexual] pleasure.[33]

Poor him [of the husband] […] We [the wife] have to understand that he has [sexual] needs.[33]

If you’re lucky enough to have someone who’ll stand by you and understands what you’re going through, or has an inkling at least, OK, but if not … each go their separate ways, that’s how it is.[38]

3.2.3. Managing Misunderstandings/Support

I feel like he understands me, that he makes a big effort to understand my pain. At the same time, I try to forget my pain, and put in an effort on my part so we don’t have to stop doing the things he loves.[34]

Since I have fibromyalgia, he has become too sensitive; if I cry, he cries with me. That makes me feel accompanied, that I think he understands my pain. Sometimes he gets so bad for my pains, that it’s my turn to console him and tell him that everything will turn out well.[35]

I left the consultation feeling really down… you feel like they’re not listening to you. He told me that he was going to send me to a psychiatrist. There was no sensitivity… so I wasn’t exactly going to talk or ask about sex.[9]

3.2.4. Vulnerability…of My Relationship

I don’t feel pretty, … I want to hide in the dark.[36]

Getting up every day and hearing that it’s hurting here or there, I know it must be draining. It’s already bad enough that I have to deal with it on a daily basis, without having to make someone else deal with it every day too.[34]

3.2.5. Faking It for Fear of Abandonment

I wonder to myself if he would ever leave me one day, because it could happen, he might get tired of dealing with it and someone else comes along who wants to go out and have fun, who can do the things he wants to do, who has things in common with him.[34]

3.3. Taking Charge of a “New Sexuality”

3.3.1. Striving for My (Our) Sex Life

For me, yes, obviously, it’s like before, just as important. I throw myself into it, because. I have to do things, I have to have a life, sex too.[24]

… If I can feel pretty, maybe I can feel better about myself…it will help me feel more desirable, which in turn will hopefully bring the sex back into our lives.[36]

3.3.2. Forgetting the Past: Taking the Initiative

I love you, and yes, you have fibromyalgia, but we’ll get through this together, you have to stop feeling guilty for not being able to do it [sex]. I’m fine…[36]

It would be good if they explained it to the partners, that when you have a strong chronic pain, you are physically not up to having a sexual relationship, and that if you need to rest while having sex, that’s quite normal, because physically, your body needs to rest.[9]

3.3.3. Changing Habits: Finding the Right Moment

I have to do it when I’m not tired—it’s not so much the frequency, but of finding other ways of doing it, whereby it’s not painful, not because of having sex, but of the correct position.[38]

We understood that we could not always have relationships, that we could when the pain was bearable.[35]

You don’t feel like it until you actually start… then you get into it and you feel like it more.[24]

3.3.4. Getting to Know Each Other: Prioritising Play and Touch

There is not much movement after penetration either, my husband knows it has to be gentle and quick.[39]

Sexuality for me before was from the genital, that is, from intercourse; we did not worry about what we felt… Now we explore ourselves, we talk, we laugh, we try things.[35]

3.3.5. Changing Positions and Using Lubricants

Sometimes, if I’m having a bad day, I may have to say, “Hey, my knee hurts, let’s not have sex in that position, let’s do it this way.”[36]

3.3.6. Exercise and Therapy

With physical exercise, yes, because you’re more active, you feel better (laughs). It helps you to get into the mood more.[24]

3.3.7. Social and Professional Support

Sexual problems in fibromyalgia are never discussed with doctors. They never bring it up, it seems that it doesn’t exist or that we don’t have sexuality. We don’t bring up the problem either.[39]

Since I’ve been coming to the association, I’ve come to understand FM. Now, being here with other people and seeing they have the same symptoms as you and everything… it’s like you understand the illness better.[9]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giorgi, V.; Sirotti, S.; Romano, M.E.; Marotto, D.; Ablin, J.N.; Salaffi, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. Fibromyalgia: One year in review 2022. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, F.; Afshari, M.; Moosazadeh, M. Prevalence of fibromyalgia in general population and patients, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2017, 37, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocyigit, B.F.; Akyol, A. Fibromyalgia syndrome: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Reumatologia 2022, 60, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzabibi, M.A.; Shibani, M.; Alsuliman, T.; Ismail, H.; Alasaad, S.; Torbey, A.; Altorkmani, A.; Sawaf, B.; Ayoub, R.; Khalayli, N.; et al. Fibromyalgia: Epidemiology and risk factors, a population-based case-control study in Damascus, Syria. BMC Rheumatol. 2022, 31, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.P.; Santo, A.S.D.E.; Berssaneti, A.A.; Matsutani, L.A.; Yuan, S.L.K. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: Literature review update. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2017, 57, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajah, A.S.; Guymer, E.K.; Leech, M.; Littlejohn, G.O. The relationship between fibromyalgia, stress and depression. Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 9, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, R.E. Assessment of women’s sexual health using a holistic, patient centered approach. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2013, 58, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Villademoros, F.; Calandre, E.P.; Rodríguez-López, C.M.; García-Carrillo, J.; Ballesteros, J.; Hidalgo-Tallón, J.; García-Leiva, J.M. Sexual functioning in women and men with fibromyalgia. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Molina, J.; Matarín, T.M.; Ramos, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Fernández-Sola, C. Social support for female sexual dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2018, 27, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, A.; Lachance, G.; Williams, F.M. Prevalence and risk factors of sexual problems and sexual distress in a sample of women suffering from chronic widespread pain. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2772–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasyali, A.S.; Taştaban, E.; Amasyali, S.Y.; Turan, Y.; Kazan, E.; Sari, E.; Erol, B.; Cengiz, M.; Erol, H. Effects of low sleep quality on sexual function, in women with fibromyalgia. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2016, 28, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lavín, M. Fibromyalgia in women: Somatisation or stress-evoked, sex-dimorphic neuropathic pain? Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhare, D.; Ahmed, S.; Watter, S. A narrative review on the difficulties associated with fibromyalgia diagnosis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2018, 10, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzichi, L.; Giacomelli, C.; Consensi, A.; Giorgi, V.; Batticciotto, A.; Di Franco, M.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. One year in review 2020: Fibromyalgia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. S123), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altıntas, D.; Melikoglu, M.A. The frequency of fibromyalgia in familial Mediterranean fever and its impact on the quality of life. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 25, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentor, J.L. Living with a contested, stigmatized illness: Experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazquez, A.; Ruiz, E.; Aliste, L.; Garcıa-Quintana, A.; Alegre, J. The effect of fatigue and fibromyalgia on sexual dysfunction in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, H.; Yilmaz, S.D.; Erkin, G. The effects of fibromyalgia syndrome on female sexual function: A controlled study. Sex. Disabil. 2012, 30, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzichi, L.; Rossi, A.; Giacomelli, C.; Scarpellini, P.; Conversano, C.; Sernissi, F.; Dellosso, L.; Bombardieri, S. The influence of psychiatric comorbidity on sexual satisfaction in fibromyalgia patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2013, 31, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Poh, L.W.; He, H.G.; Chan, W.C.; Lee, C.S.; Lahiri, M.; Mak, A.; Cheung, P.P. Experiences of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2017, 26, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E. Fibromyalgia: Recent advances in diagnosis, classification, pharmacotherapy and alternative remedies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslow, B.T.; Vandal, C.; Dang, L. Fibromyalgia: Diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2023, 107, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Matarín Jiménez, T.M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Correa, M.; Antequera, L.H.; Granero-Molina, J. Perceptions about the sexuality of women with fibromyalgia syndrome: A phenomenological study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Vives-Cases, C.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Gil-González, D. Patients’ and professionals’ views on managing fibromyalgia. Pain Res. Manag. 2013, 18, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengshoel, A.M.; Sim, J.; Ahlsen, B.; Madden, S. Diagnostic experience of patients with fibromyalgia—A meta-ethnography. Chronic Illn. 2018, 14, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climent-Sanz, C.; Morera-Amenós, G.; Bellon, F.; Pastells-Peiró, R.; Blanco-Blanco, J.; Valenzuela-Pascual, F.; Gea-Sánchez, M. Poor sleep quality experience and self-management strategies in fibromyalgia: A qualitative metasynthesis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 522, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Qualitative Research. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools524 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centurión, N.; Sanches, R.; Ribeiro, E.J. Meanings about sexuality in women with fibromyalgia: Resonances of religiosity and morality. Psicol. Estud. 2020, 25, e44849. [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria, J.P.; Gers, M. Repercussions of chronic pain on couple’s dynamics: Perspectives of women with fibromyalgia. Rev. Colomb. Psicol. 2019, 29, e2923. [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria, J.P.; Gers, M. Changes in erotic Expression in Women with Fibromyalgia. Paideia 2019, 28, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Iglesias, P.; Crump, L.; Henry, J.L.; LaChapelle, D.L.; Byers, E.S. The sexual lives of women living with fibromyalgia: A qualitative study. Sex. Disabil. 2022, 40, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.M.; Crofford, L.J.; Mease, P.J.; Burgess, S.M.; Palmer, S.C.; Abetz, L.; Martin, S.A. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 73, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Vives-Cases, C.; Goicolea, I. “I’m not the woman I was”: Women’s perceptions of the effects of fibromyalgia on private life. Health Care Women Int. 2016, 37, 836–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García Campayo, J.; Aida, M. Sexuality in patients with fibromyalgia: A qualitative study. Arch. Psiquiatr. 2004, 67, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L.P.; Ferreira, M.A. Fibromyalgia from the gender perspective: Triggering, clinical presentation and coping. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2023, 32, e20220299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricoy-Cano, A.J.; Cortés-Pérez, I.; Del Carmen Martín-Cano, M.; De La Fuente-Robles, Y.M. Impact of fibromyalgia syndrome on female sexual function: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 28, e574–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besiroglu, M.D.H.; Dursun, M.D.M. The association between fibromyalgia and female sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2019, 31, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristano, A.G. The impact of rheumatic diseases on sexual function. Rheumatol. Int. 2009, 29, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayhan, F.; Küçük, A.; Satan, Y.; İlgün, E.; Arslan, Ş.; İlik, F. Sexual dysfunction, mood, anxiety, and personality disorders in female patients with fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalichman, L. Association between fibromyalgia and sexual dysfunction in women. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009, 28, 365–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alorfi, N.M. Pharmacological treatments of fibromyalgia in adults; overview of phase IV clinical trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1017129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Atzeni, F.; Gorla, R.; Kosek, E.; Choy, E.H.; Bazzichi, L.; Häuser, W.; Ablin, J.N.; Aloush, V.; et al. Fibromyalgia position paper. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. S130), 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natelson, B.H.; Lin, J.S.; Lange, G.; Khan, S.; Stegner, A.; Unger, E.R. The effect of comorbid medical and psychiatric diagnoses on chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann. Med. 2019, 51, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, H.M.; Yunusa, I.; Goswami, H.; Sultan, I.; Doucette, J.A.; Eguale, T. Comparison of amitriptyline and us food and Drug Administration-Approved Treatments for Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2212939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Overmeire, R.; Vesentini, L.; Vanclooster, S.; Muysewinkel, E.; Bilsen, J. Sexual desire, depressive symptoms and medication use among women with fibromyalgia in Flanders. Sex. Med. 2022, 10, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, G.B.; Sato, T.O.; Miwa-Cerqueira, T.; Bifani, B.E.; Rocha, A.P.R.; Carvalho, C. Pelvic floor dysfunctions in women with fibromyalgia: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 282, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Di Carlo, M.; Farah, S.; Giorgi, V.; Mosca, N.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. Overactive bladder syndrome and sexual dysfunction in women with fibromyalgia and their relationship with disease severity. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, P.L.; De Civita, M.; Bernatsky, S.; Kang, H.; Baron, M. Does psychological vulnerability determine health-care utilization in fibromyalgia? Rheumatology 2003, 42, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenbaecher, M.; Dezutter, J.; Kohls, N.; Sigl, C.; Vallejo, M.A.; Rivera, J.; Bauerdorf, F.; Schelling, J.; Vincent, A.; Hirsch, J.K.; et al. Struggling with adversities of life: The role of forgiveness in patients suffering from fibromyalgia. Clin. J. Pain 2017, 33, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasileios, P.; Styliani, P.; Nifon, G.; Pavlos, S.; Aris, F.; Ioannis, P. Managing fibromyalgia with complementary and alternative medical exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Rheumatol. Int. 2022, 42, 1909–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohabbat, A.B.; Mahapatra, S.; Jenkins, S.M.; Bauer, B.A.; Vincent, A.; Wahner-Roedler, D.L. Use of complementary and integrative therapies by fibromyalgia patients: A 14-year follow-up study. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 16, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varinen, A.; Vuorio, T.; Kosunen, E.; Koskela, T.H. Experiences of patients with fibromyalgia at a Finnish Health Centre: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 28, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Alcalá, P.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Coín-Pérez-Carrasco, M.D.R.; Ramos-Rodríguez, C.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Granero-Molina, J. Sexuality in male partners of women with fibromyalgia syndrome: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roitenberg, N.; Shoshana, A. Physiotherapists’ accounts of fibromyalgia: Role-uncertainty and professional shortcomings. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centurión N.B., et al., 2020 [32] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Sanabria, J. P., and Gers, M. (2019, a) [33] | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Sanabria, J. P., and Gers, M. (2019, b) [34] | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Santos-Iglesias, P., et al. (2022) [35] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Matarin Jiménez et al., 2017 [24] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Arnold, L.M., et al., 2008 [36] | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2016 [37] | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| García Campayo, J. et al., 2004 [38] | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ |

| Granero-Molina, J., et al., 2018 [9] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Stage | Description | Steps |

|---|---|---|

| STAGE 1 | Text coding | Recall review question Read/re-read findings of the studies Line-by-line inductive coding Review of codes in relation to the text |

| STAGE 2 | Development of descriptive themes | Search for similarities/differences between codes Inductive generation of new codes Write preliminary and final report |

| STAGE 3 | Development of analytical themes | Inductive analysis of sub-themes Individual/independent analysis Pooling and group review |

| Author Año | País | Muestra (FMSW) | Edad (Años) | Tiempo Entrevista | Data Collection | Data Analysis | Main Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centurión, N.B., et al. 2020 [32] | Brasil | 6 | 40–60 | 1 h 30 min | DGs | Content analysis | Religion and morals affect women with FMS |

| Sanabria, J.P., et al. (2019, a) [33] | Colombia | 15 | 23–60 | No | IDI | Organisation, segmentation and correlation | Carer roles and gender influence couple dynamics |

| Sanabria, J.P., et al. (2019, b) [34] | Colombia | 15 | 23–60 | No | IDI | Organisation, segmentation and correlation | Feminine viewpoint of FMS influences their erotic expression |

| Santos-Iglesias, P., et al. (2022) [35] | Canada | 16 | ≥21 | 60–90 min | SSI | Inductive thematic analysis | Multi-dimensional nature of sexual wellbeing in women with FMS |

| Matarín Jiménez, T., et al. (2017) [24] | España | 13 | 22–56 | 40 min | FG, IDI | Gadamer’s phenomenological analysis | FMS affects identity and relationship with partners |

| Arnold, L.M., et al. (2008) [36] | USA | 48 | >18 | 2 h | FG | Strauss and Corbin’s techniques | FMS has a negative impact on quality of life |

| Briones-Vozmediano, E., et al. (2016) [37] | España | 13 | 24–61 | 60–90 min | SSI | Thematic analysis | Healthcare providers can help to improve lifestyle in women with FMS. |

| García Campayo, J., et al. 2004 [38] | España | 27 | No | 60–90 min | SSI, FG | Thematic analysis | FMS limits feminine sexuality, but is not discussed with doctors |

| Granero-Molina, J., et al. 2018 [9] | España | 13 | 22–56 | 40 min | FG, IDI | Gadamer’s phenomenological analysis | Lack of formal support regarding fibromyalgia patient’s sexuality |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| 3.1. “I Want to, but I Can’t”: A Shift in Feminine Sexuality | 3.1.1. Pain/Stiffness Limits Pleasure and Desire 3.1.2. Irritability and Low Mood 3.1.3. Decreased Frequency/Difficulty in Having Orgasm 3.1.4. Pharmacological Treatment Does Not Help Sexuality 3.1.5. Having Sex “for Your Partner”: Avoiding Sexual Encounters |

| 3.2. Resetting Sex Life and Intimacy | 3.2.1. I know It’s Not Mutual 3.2.2. Bearing the Moral Burden 3.2.3. Managing Misunderstanding/Support 3.2.4. Vulnerability … of My Relationship 3.2.5. Faking It for Fear of Abandonment |

| 3.3. Taking Charge of a “New Sexuality” | 3.3.1. Striving for My (our) Sex Life 3.3.2. Forgetting the Past: Taking Initiative 3.3.3. Changing Habits: Finding the Moment 3.3.4. Getting to Know Each Other: Prioritising Play and Touch 3.3.5. Changing Positions and Using Lubricants 3.3.6 Exercise and Therapy 3.3.7. Social and Professional Support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Granero-Molina, J.; Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.d.M.; Dobarrio-Sanz, I.; Correa-Casado, M.; Ramos-Rodríguez, C.; Romero-Alcalá, P. Sexuality in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202762

Granero-Molina J, Jiménez-Lasserrotte MdM, Dobarrio-Sanz I, Correa-Casado M, Ramos-Rodríguez C, Romero-Alcalá P. Sexuality in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202762

Chicago/Turabian StyleGranero-Molina, José, María del Mar Jiménez-Lasserrotte, Iria Dobarrio-Sanz, Matías Correa-Casado, Carmen Ramos-Rodríguez, and Patricia Romero-Alcalá. 2023. "Sexuality in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202762

APA StyleGranero-Molina, J., Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M. d. M., Dobarrio-Sanz, I., Correa-Casado, M., Ramos-Rodríguez, C., & Romero-Alcalá, P. (2023). Sexuality in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies. Healthcare, 11(20), 2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202762