“What Do We Know about Hope in Nursing Care?”: A Synthesis of Concept Analysis Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search and Selection Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction

| Title/Author/ Date/Country | Concept Analysis Method | Objectives | Antecedents | Attributes/Surrogate Terms/Related Attributes | Consequences | Empirical Referents | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope in palliative care nursing: concept analysis Guedes et al. (2021) Portugal [29] | Walker and Avant’s method | To develop hope in palliative care as an evidenced-based nursing concept; to analyze its attributes, antecedents, and consequences | - Positive attitude - Uncertainty - Spirituality - Symptom control - Fatigue - Hopelessness - Interpersonal relationships - Realistic goals/objectives - Depression - Trust - Relationships with professionals - Existential suffering - Request for early death - Nonverbal indications of hope - Keeping busy - Religiosity - Holistic care - Clinical information - Life narrative - Physical condition - Change focus - Preparation for death - Positive events - Diagnosis and chemotherapy time - Hope in healing - Prognostic uncertainty - Resilience | - Positive outcome expectancy: - Inner strength - Coping mechanism - Goal - Spirituality/religion - Expectation - Hope in healing - Prognostic acceptance - Optimism/positive - Living a normal life - Gratitude - Miracle - Security - Protecting patients from distress and suffering - Process-oriented towards the present and the future: - Positive expectancies - Irrational, dynamic, multidimensional, life value - Phenomenon - Living in the moment, generalized, multifaceted, individualized, subjective, attitude | - Stress reduction - Resilience - Quality of life - Peaceful death - Life extension - Improvement - Legacy - Positive future for family and friends - Survival - Acceptance - Holistic care - New meanings and objectives - Future gains | “Adherence to therapy, a sense of well-being, having a positive attitude, and the ability to engage in self-management, despite physical limitations” (p. 341). Also: The Hope Communication Tool, Beck Hopelessness Scale, Snyder Hope Scale, Herth Hope Index, Hopelessness Assessment in Illness, Miller Hope Scale, Nowotny Hope Scale. | “Hope is central to the adjustment process in palliative care when trying to maintain a sense of normalcy and developing cognitive, social, behavioral, and transcendental strategies to improve confidence” (p. 342) |

| A Critical Analysis of the Concept of Hope: The Nursing Perspective Nweze, Agom, and Nwankwo (2013) Nigeria [30] | Walker and Avant’s method | “To examine the concept of hope within the healthcare context, with a particular focus on hospital nursing as presented in the literature” (p. 1027). | - Suffering, pain, and despair brought about by chronic and debilitating diseases - Pivotal events of life - Stressful stimuli such as loss, hardship, and uncertainty - Positive personal attributes - Connectedness with God - Acknowledgement of a threat | - Spirituality - Goals - Comfort - Caring - Interpersonal relationships - Control - Expectation - Life review | - Ability to achieve goals - Being able to cope and experiencing life satisfaction despite the limitations brought about by illness | “Adherence to medication, sense of well-being, good positive attitude, and being able to engage in the management of self despite physical limitations” (p. 1029). | “Hope is experienced within the hospital culture, events, and interactions that occur between patients and healthcare givers can provide the meaning or understanding of what happens in current practice” (p. 1030). |

| Hope and Parents of the critically ill new-born: a concept analysis Amendolia (2010) USA [31] | Walker and Avant’s method | To examine the concept of hope in parents of critically ill new-borns | - Negative and stressful stimuli - Suffering or loss - Predicament or threat - Uncertainty | - Future orientation - Goal setting - Realism - Energy or activity processing - Positive feeling or optimism | - Ability to cope - Certainty - Improved health - Improved quality of life - Peace - New perspective - Strength - Empowerment | The Herth Hope Scale (HHS), the Hope Index Scale, the Childrens’ Hope Scale, the Stoner Hope Scale, the Miller Hope Scale, and the Nowotny Hope Scale (p. 143). The Hope Assessment Guide was developed to indicate the progression and development of hope. | “Hope plays a role in the day-to-day experiences of families in this setting and can improve the overall experience at such a stressful crossroad. Fostering and maintaining hope should be a priority for those entrusted with the care of the critically ill new-born” (p. 144). |

| Hope in early-stage dementia: a concept analysis Cotter (2009) USA [32] | Walker and Avant’s method | “To explore hope in early-stage dementia and to identify the dynamics and components of the hope experience” (p. 232) | - Awareness or recognition of the diagnosis - Managing a sense of self in the context of relationships and social identities | - Hope in the experience of loss and ongoing adjustment - Future orientation of hope - Hope and social identity and social network - Hope and adaptation to daily living (p. 233). | - Positive changes in the self-concept -Growth opportunities. | “Hope is a process occurring within the individual, whose outcomes can be measured by self-report; clinical scales; and observations of body language, posture, facial expressions, and behavior” (p. 236). | “Hope is central to the adjustment process in early-stage dementia when trying to maintain a sense of normalcy and developing cognitive, social, and behavioral strategies to improve confidence. Maintaining hope, helping others, and living within a supportive social network can positively influence adaptations to daily living and to the preservation of self-concept” (p. 235). |

| An exploration of hope as a concept for nursing Tutton, Seers, and Langstaff (2009) United Kingdom [26] | Morse’s pragmatic utility approach | To examine the concept of hope within the context of healthcare, with a focus on hospital nursing, as portrayed in the literature | Not provided | - Hope as an expectation for the future - Hope as a cognitive process - Goal attainment | Not provided | Not provided | Hope is classified as an expectation or a cognitive process encompassing realistic and unrealistic hope. |

| Paradox of Hope in Patients Receiving Palliative Care: A Concept Analysis Tanis, DiNapoli, and Hampshire (2008) [33] UK | Walker and Avant’s method | To conceptually define the paradox of hope, to operationalize the concept, and to apply the concept to nursing practice | - Certainty vs. uncertainty - Comfort vs. discomfort - Goals vs. not caring - Peaceful vs. grieving - Acceptance vs. struggle - Control vs. lack of control - Companionship vs. abandonment - Joy vs. depression Reaching for life vs. acceptance of dying | - Dynamic quality along a continuum - Personal experience of hope - Continuous present | - Coping skills - Support and companionship - Value of the individual - Personal relationship with a higher power - Healthcare providers understand hope | The structured interview assessment of symptoms and concerns, Beck Depression Inventory-II. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Herth Hope Index (HHI). | Hope is the lived experience of the patient searching for meaning in life, engaged in a continuous dialogue about the consequences of dying. As a result of this dialogue, attitudes change, choices are considered, and life is reshaped |

| Hope: more than a refuge in a storm. A concept analysis using the Wilson method and the Norris method. Sachse (2007) USA [34] | Wilson’s conceptual model | To provide an operational definition of hope | - Genetic temperament - Scripting from significant others - Experiences (personal and observed) - Memories, beliefs, and values - Wished for object - Dilemma - Crisis | - Universal yet unique to each individual - Dynamic in its presence - Enabling | - Resilience - Transcendence - Positive psychologically, spirituality, physiologically | Not provided | Hope is defined as “a multidimensional construct arising from our memories, beliefs, and values” (p. 1552); hope is part of all activities and thoughts that strengthen the spirit, facilitating behavior to elicit an outcome or promote a level of comfort while impacting life quality. |

| Hope in terminal illness: an evolutionary concept analysis. Johnson (2007) New Zealand [35] | Rodgers’ evolutionary model | To clarify the concept of hope as perceived by patients with a terminal illness, to develop hope as an evidence-based nursing concept, and to contribute new knowledge and insights about hope to the relatively new field of palliative care, endeavouring to maximize the quality of life of terminally ill patients in the future | - Being physically unwell, pain, discomfort - A medical diagnosis of a terminal illness - Uncertainty - Fear of dearth - Feelings of devaluation of personhood | - Personal qualities (such as inner strength, determination, and an optimist state of mind) - Spirituality - Goals - Comfort - Help/caring - Interpersonal relationships - Control - Legacy - Life review - Positive expectations | - Feeling calm, peaceful, and accepting the situation - Problem-solving approach - Coping mechanism - Optimize the quality of life | Not provided | “A working definition of hope in terminal illness is that it is a calm, emotional hope that is global in nature, focusing on the hopes of loved ones rather than on a fulfilling, prosperous future. Hope is living in the present and spending quality time with significant others. An enrichment of being is more important than having or doing. Hope is directed towards comfort, peace, leaving a legacy, and considering spiritual dimensions. Hope is about valuing the gift of each day with the positive expectation of a few more good days to follow. Patients review the life they have led and attach meaning to their past achievements, which equates to hope and maximizes quality of life.” (p. 458) |

| One step towards the understanding of hope: a concept analysis. Benzein and Saveman (1998) Sweden [36] | Walker and Avant’s method | To elucidate the concept of hope | Stressful stimuli - Loss - Life-threatening situations - Temptation to despair | - Future orientation - Positive expectation - Intentionality - Activity - Realism - Goal setting - Interconnectedness | - Ability to cope - Renewal - New strategies - Peace - Improved quality of life - Physical health | Not provided. | “Hope is a human phenomenon with no sharp boundaries, related and interwoven with other phenomena, e.g., expectations and desire. Hope can be seen as one link in a field of emotions such as hope–joy–enthusiasm or expectation–yearning–confidence–hope. Hope can be seen as a personal experience; the only true understanding comes from sharing people’s narrated experiences of hope” (pp. 327–328). |

| An analysis of the concept of hope in the adolescent with cancer. Hendricks-Ferguson (1997) USA [37] | Walker and Avant’s method | “To provide a sample concept framework for paediatric oncology nurses that will assist them in applying the conceptual attributes in their clinical practice with adolescents diagnosed with cancer” (p. 73). | - Previous experience in trusting and loving relationships with significant others - Previous experience with successful learning experiences - A history of successful goal obtainment - A stressful stimulus, such as being diagnosed with cancer (p. 77) | - Positive thinking or optimism - Reality-based and future-oriented goals - Positive future for self or others - Positive support systems | - The individual expresses new feelings of safety or comfort - The individual formulates new and realistic goals - The individual demonstrates a belief that what is hoped for is possible - The individual expresses confidence in the future - The individual expresses a concern for and a focus on others in addition to self The individual conveys trust in supportive actions from others (p. 77). | The Hopefulness Scale for Adolescents (HAS) is a 24-item, visual analogue scale designed to quantify the degree of positive future orientation an adolescent feels at the time of measurement. “A short interview or using an existing spiritual well-being assessment scale in combination with the HSA is recommended because of the HSA’s lack of any items related to spiritual well-being” (p. 78). | The theoretical construct of adolescent hopefulness is defined as “the degree to which an adolescent possesses a comforting or life-sustaining, reality-based belief that a positive future exists for self or others” (p. 77). The concept of hope for the adolescent is currently in the early stage of development and understanding. |

| Simultaneous concept analysis of spiritual perspective, hope, acceptance, and self-transcendence. Haase et al. (1992) USA [25] | A simultaneous concept analysis based on the Wilson method and described by Walker and Avant | “To clarify the four concepts simultaneously, offering mutually exclusive theoretical definitions for each concept while highlighting their interrelationships and distinguishing characteristics” (p. 141). | - A pivotal life event or a stressful stimulus such as loss, major decisions, hardship, suffering, and uncertainty - Positive personal attributes - Connectedness with others or God, a feeling of uncertainty, uneasiness, or other related feelings of discomfort (p. 143) | - Future-oriented - An energized, action orientation termed variously as activity - Either a generalized or particularized goal or a desired outcome | - A sense of personal competency in meeting goals - A ‘winning position’ - Peace - Ability to transcended | Not provided. | Hope is “defined as an energized mental state involving feelings of uneasiness or uncertainty and characterized by a cognitive, action-oriented expectation that a positive future goal or outcome is possible” (p. 143). Clearly, spiritual perspectives, hope, acceptance, and self-transcendence are just three of the many dynamic psychosocial processes requiring further theoretical and empirical attention. |

| The concept of hope revised for nursing Stephenson (1991) USA [38] | Walker and Avant’s method | To review definitions and conceptual usages of the word “hope” from the literature and answer the conceptual question of “what is hope?” (p. 1456) | - Crises (could include a loss, a life-threatening situation, a hardship, or a change - A difficult decision or challenge - Anything that would be significant to the person | - The object of hope is meaningful to the person - Hope is a process involving thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and relationships - There is an element of anticipation - There is a positive future orientation, which is grounded in the present and linked with the past” (p. 1459) | - New perspective (hope seems to energize, empower and strengthen the person) - People with their hopes fulfilled, describe themselves as invigorated, full of purpose, renewed, calm and encouraged” (p. 1459). | Not provided. | “From these definitions and attributes, a tentative definition of hope can be proposed; hope is an anticipation, accompanied by desire and expectation, of a positive possible future” (p. 1457). |

| Hope in elderly with chronic heart failure. Concept analysis Caboral et al. (2012) USA [39] | Walker and Avant’s method | “To explore the construct of hope in elderly adults with chronic heart failure” (p. 406) | - Suffering and despair brought about by heart failure illness (decreased functional capacity) | - Future orientation: The future in older adults is the anticipation of a future in each day lived, and they look at the past instead of the nurture. Past successes nurture their hope. They hope that their condition does not worsen - Sense of limitation: “The HF illness trajectory can be unpredictable and range from being able to function without difficulties to a severely limited functional capacity. Hopeful individuals with HF maintain their involvement in life despite the limitations imposed by the illness trajectory” (p. 408) | - The ability to achieve goals “Goals in HF include being able to cope and experiencing life satisfaction despite limitations brought by the illness” (p. 410) | “Adherence to therapy, a sense of well-being, having a positive attitude, and the ability to engage in self-management despite physical limitations could be empirical referents of hope” (p. 410) | “Hope is an intangible concept that is difficult to observe and is imbedded within someone’s personal experience. It is a belief that something positive without any guaranteed expectation that it will occur” (p. 410) |

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

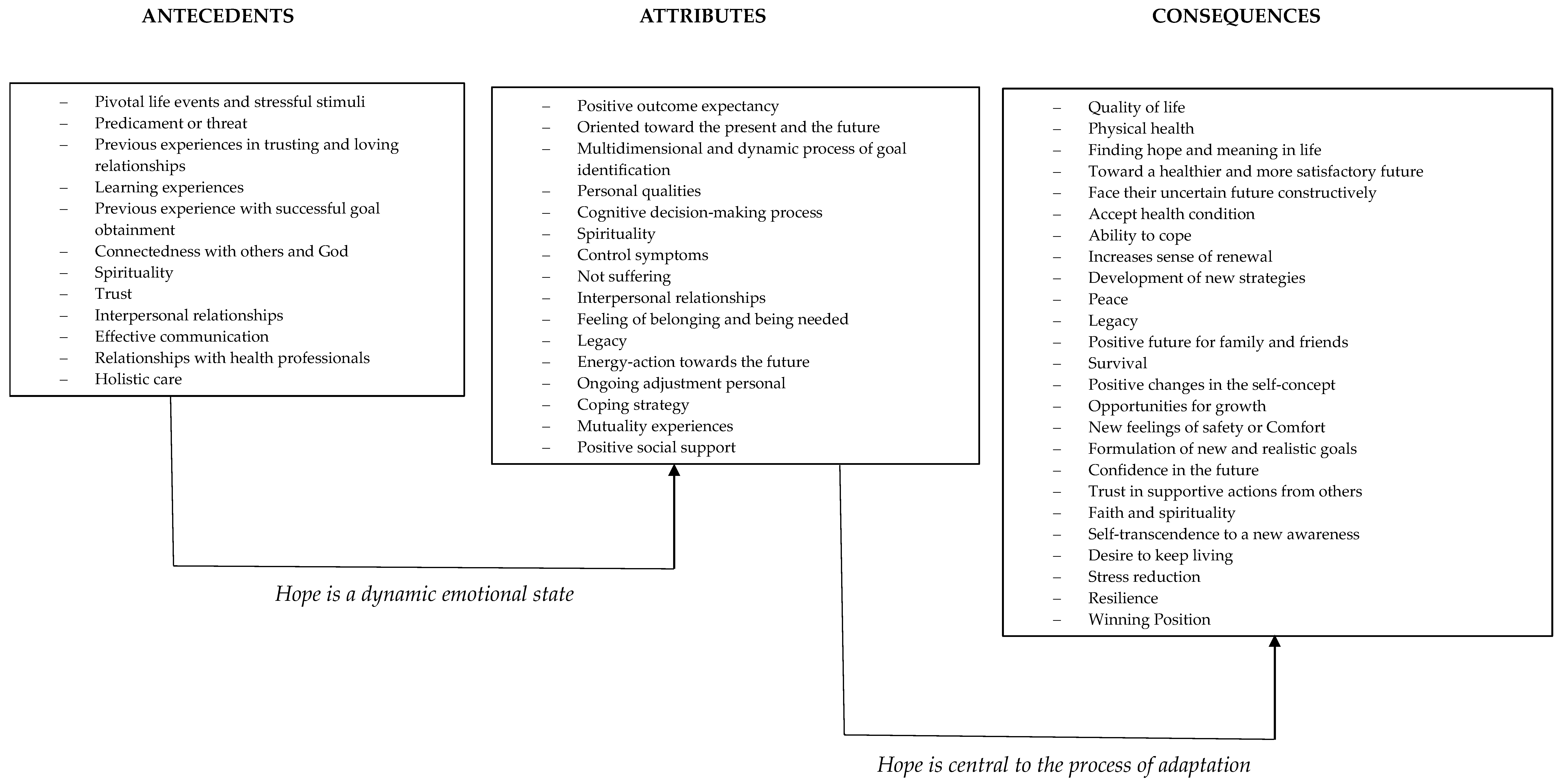

3.1. The Antecedents of Hope

3.2. The Attributes of Hope

3.3. The Consequences of Hope

3.4. Updating the Definition of Hope

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Study Limitations

4.2. Implications for Nursing Practice and Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lohne, V. ‘Hope as a lighthouse’ A meta-synthesis on hope and hoping in different nursing contexts. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 36, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustøen, T. Hope: A Health Promotion Resource. In Health Promotion in Health Care—Vital Theories and Research; Haugan, G., Eriksson, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsman, E. Hope in Health Care: A Synthesis of Review Studies. In Historical and Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Hope; van den Heuvel, S.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleeging, E.; van Exel, J.; Burger, M. Characterizing Hope: An Interdisciplinary Overview of the Characteristics of Hope. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 1681–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doe, M. Conceptual Foreknowing’s: An Integrative Review of Hope. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2020, 33, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W. Living with Hope Program. In Hospice Palliative Care and Bereavement Support; Holtslander, L., Peacock, S., Bally, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufault, K.; Martocchio, B. Hope: Its spheres and dimensions. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 1985, 20, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioli, A. The Psychology of Hope: A Diagnostic and Prescriptive Account. In Historical and Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Hope; van den Heuvel, S.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farran, C.J.; Herth, K.A.; Popovich, J.M. Hope and Hopelessness: Critical Clinical Constructs; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A.; Charepe, Z.; Dixe, M. Hope-based interventions in chronic disease: An integrative review in the light of Nightingale. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl. S5), e20200283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council of Nurses. CIPE® Versão 2019. Classificação Internacional Para a Prática de Enfermagem; Ordem Dos Enfermeiros: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Guo, Y.-J.; Tang, Q.; Yang, L. Effectiveness of nursing intervention for increasing hope in patients with cancer: A meta-analysis. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.; Garcia-Vivar, C.; Neris, R.; Alvarenga, W.d.A.; Nascimento, L.C. The experience of hope in families of children and adolescents living with chronic illness: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3246–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, K.; Kim, E.; Chen, Y.; Wilson, M.F.; Worthington, E.L., Jr.; VanderWeele, T.J. The role of hope in subsequent health and well-being for older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Glob. Epidemiol. 2020, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snilstveit, B.; Oliver, S.; Vojtkova, M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Wong, F.; Lee, P. A Brief Hope Intervention to Increase Hope Level and Improve Well-Being in Rehabilitating Cancer Patients: A Feasibility Test. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819844381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Scheven, E.; Nahal, B.K.; Kelekian, R.; Frenzel, C.; Vanderpoel, V.; Franck, L.S. Getting to Hope: Perspectives from Patients and Caregivers Living with Chronic Childhood Illness. Children 2021, 8, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.Y.; Quanyu, L.; Fuzhong, Z. Varieties of Hope Among Family Caregivers of Patients with Lymphoma. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gřundělová, B.; Stanková, Z. Hope in Homeless People: Potencial for Implementation of Person-Centred Planning in Homeless Shelters? Practice 2019, 32, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querido, A.; Laranjeira, C.; Dixe, M. Hope in a Depression Therapeutic Group: A Qualitative Case Study. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20201309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A. Hope and Optimism as an Opportunity to Improve the “Positive Mental Health” Demand. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 827320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A. The multidimensional model of hope as a recovery-focused practice in mental health nursing. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 75, e20210474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.S.; Stokes, L. Hope promoting strategies of registered nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Lourenço, M.; Charepe, Z.; Nunes, E. Hope promoting interventions in parents of children with special health needs: A scoping review. Enferm. Glob. 2019, 53, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J.; Britt, T.; Coward, D.; Leidy, N.K.; Penn, P.E. Simultaneous Concept Analysis of Spiritual Perspective, Hope, Acceptance and Self-transcendence. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1992, 24, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutton, E.; Seers, K.; Langstaff, D. An exploration of hope as a concept for nursing. J. Orthop. Nurs. 2009, 13, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, C.; Marchetti, E.; Gurgel, L.; Busnello, F.M.; Reppold, C.T. Optimism and Hope in Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, A.; Carvalho, M.; Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A.; Charepe, Z. Hope in palliative care nursing: Concept analysis. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2021, 27, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nweze, O.; Agom, A.; Agom, J.; Nwankwo, A. A Critical Analysis of the Concept of Hope: The Nursing Perspective. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2013, 4, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Amendolia, B. Hope and parents of the critically ill newborn: A concept analysis. Adv. Neonatal Care 2010, 10, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, V. Hope in Early-Stage Dementia. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2009, 10, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanis, S.; DiNapoli, P. Paradox of Hope in Patients Receiving Palliative Care: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Hum. Caring 2008, 12, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, D. Hope: More than a refuge in a storm. A concept analysis using the Wilson method and the Norris method. Int. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. Res. 2007, 13, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. Hope in terminal illness: An evolutionary concept analysis. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2007, 13, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzein, E.; Saveman, B. One step towards the understanding of hope: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1998, 35, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks-Ferguson, V.L. An analysis of the concept of hope in the adolescent with cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Assoc. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurses 1997, 14, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, C. The concept of hope revisited for nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 1991, 16, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caboral, M.; Evangelista, L.; Whetsell, M. Hope in elderly adults with chronic heart failure. Concept analysis. Invest. Educ. Enferm. 2012, 30, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.; Avant, K. Strategies for theory construction nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, B.; Knafl, K. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reder, E.; Serwint, J. Until the Last Breath. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O´Connor, P. Hope: A concept for home care nursing. Spirit. Care 1996, 1, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofthagen, R.; Fagerstrøm, L. Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis—A valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 24, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redlich-Amirav, D.; Ansell, L.J.; Harrison, M.; Norrena, K.L.; Armijo-Olivo, S. Psychometric properties of Hope Scales: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 72, e13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, C.A.; Cassarotti, M.S.; Piolli, K.C.; Matsuda, L.M.; Wakiuchi, J. The feeling of hope in cancer patients: An existential analysis. Rev. Rede Enferm. Nordeste 2014, 15, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counted, V.; Pargament, K.I.; Bechara, A.O.; Joynt, S.; Cowden, R.G. Hope and well-being in vulnerable contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic: Does religious coping matter? J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Befecadu, F.B.P.; Rodrigues, M.G.D.R.; Larkin, P.; Pautex, S.; Dixe, M.A.; Querido, A. Exercising Hope in Palliative Care Is Celebrating Spirituality: Lessons and Challenges in Times of Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 933767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquette, K.M. Perspectives on Hope of Hospice and Palliative Care Nurses. Open Access Dissertations. 2015. Paper 400. Available online: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/400 (accessed on 23 September 2023).

| Definition of Hope—Code 10009095 (ICNP, 2019) | Proposal of Hope Definition for ICNP® |

|---|---|

| Emotion: Feelings of having possibilities, trust in others and the future, zest for life, expression of reasons and will to live, inner peace, optimism, associated with setting goals and mobilization of energy. | A dynamic emotional state, multidimensional energy that evokes a positive outcome expectancy and is process-oriented toward the present and the future. Depending on the context, hope can focus on living a fulfilling life around important people, legacy, spiritual dimensions, and maximizing quality of life. Hope is central to adapting to uneasiness or uncertainty. It is characterized by a cognitive, action-oriented expectation that a positive future goal or outcome is possible. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antunes, M.; Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A.; Charepe, Z. “What Do We Know about Hope in Nursing Care?”: A Synthesis of Concept Analysis Studies. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202739

Antunes M, Laranjeira C, Querido A, Charepe Z. “What Do We Know about Hope in Nursing Care?”: A Synthesis of Concept Analysis Studies. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202739

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntunes, Mónica, Carlos Laranjeira, Ana Querido, and Zaida Charepe. 2023. "“What Do We Know about Hope in Nursing Care?”: A Synthesis of Concept Analysis Studies" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202739

APA StyleAntunes, M., Laranjeira, C., Querido, A., & Charepe, Z. (2023). “What Do We Know about Hope in Nursing Care?”: A Synthesis of Concept Analysis Studies. Healthcare, 11(20), 2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202739