Effects of a Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program on Nursing Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Participants

2.3. Research Variables

2.3.1. Attitude toward Smoking Cessation Interventions

2.3.2. Self-Efficacy of Smoking Cessation Interventions

2.3.3. Intention to Deliver Smoking Cessation Intervention

2.4. Research Process

2.4.1. Researcher Preparation

2.4.2. Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program

- (1)

- Smoking cessation counseling education module for pre-learning

- (2)

- Smoking cessation counseling education program

2.4.3. Pre-Test

2.4.4. Post-Test

2.5. Ethical Consideration

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity Verification of Participants’ General Characteristics and Study Variables

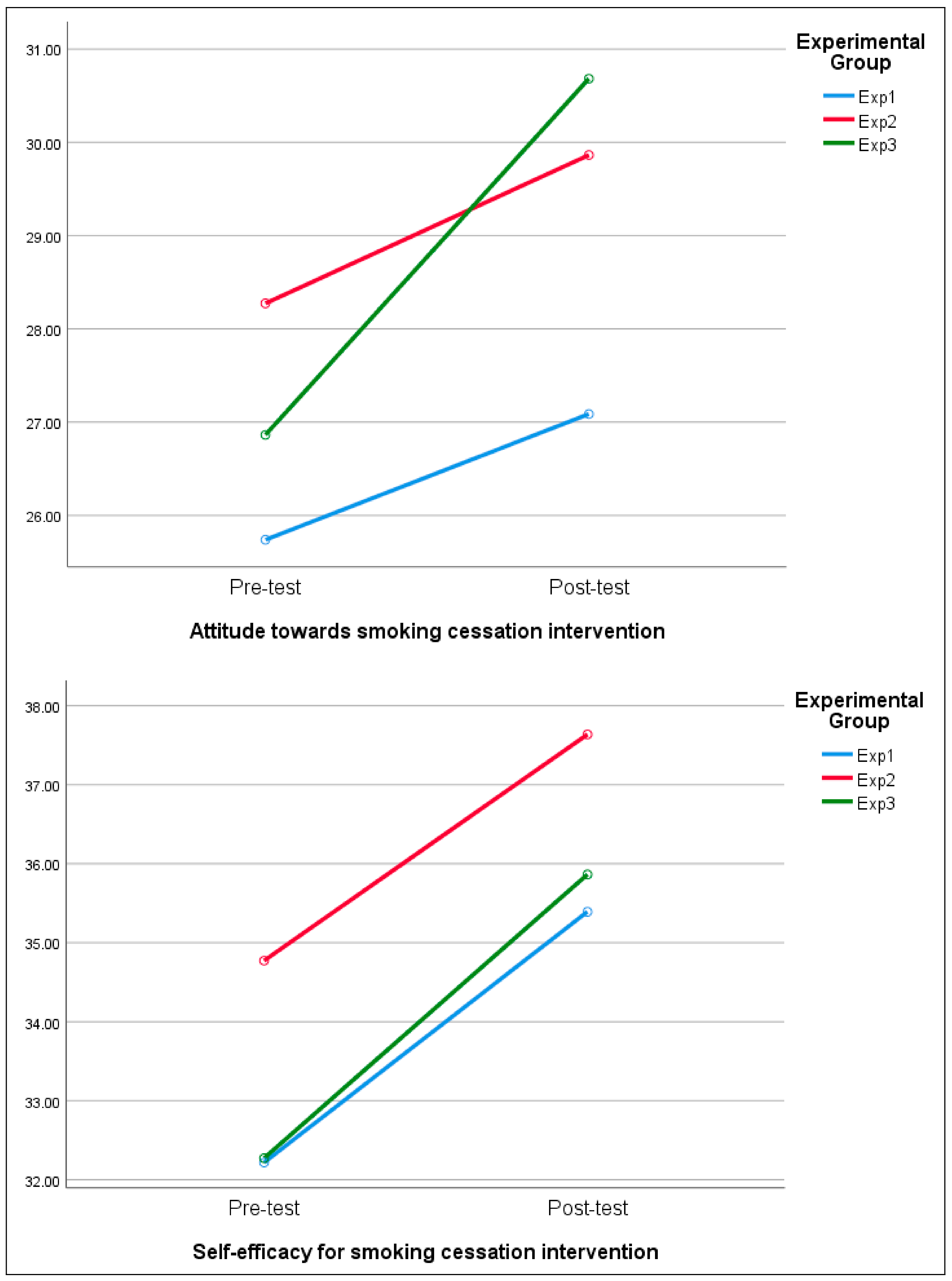

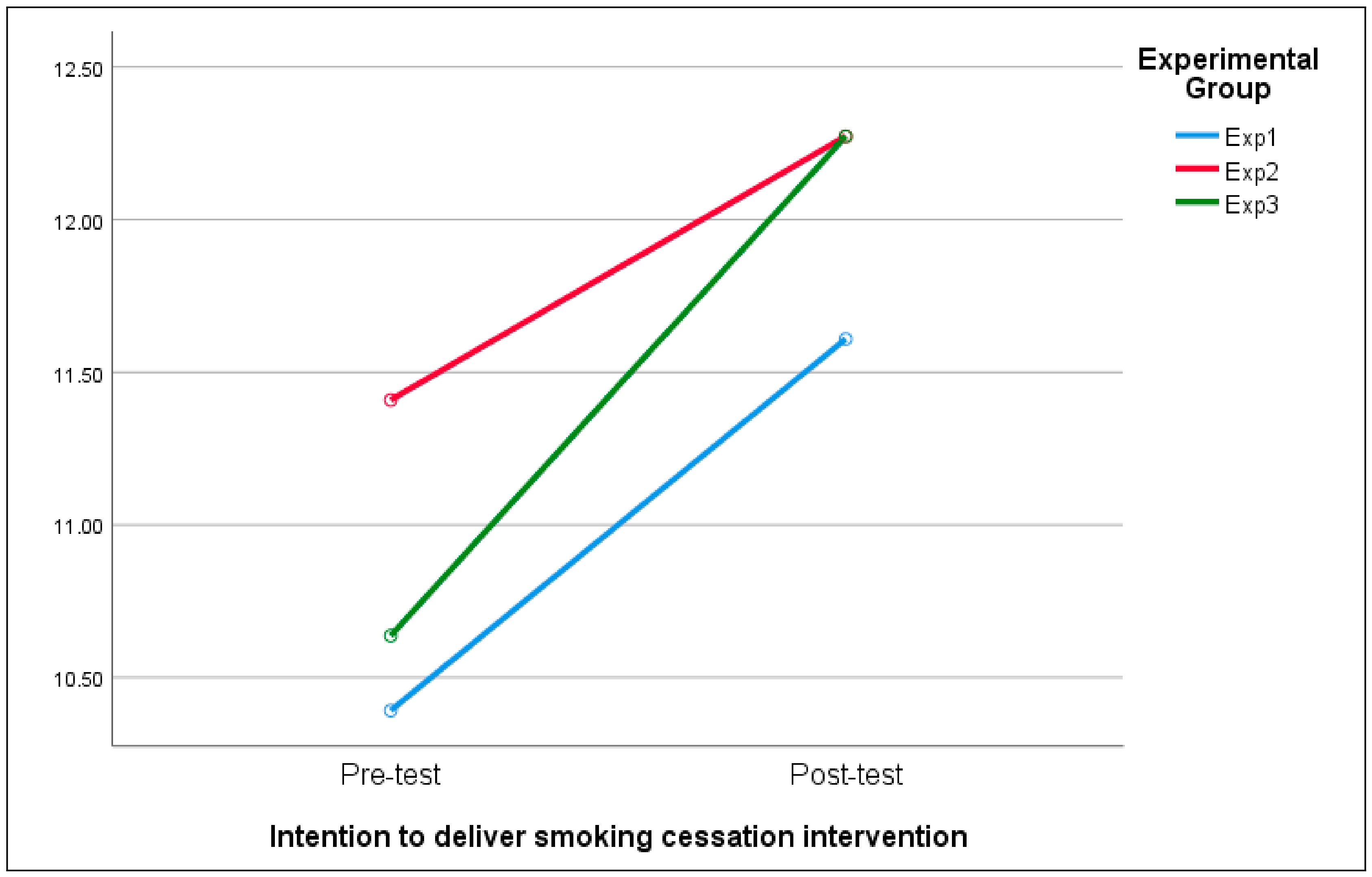

3.2. Effects of Attitude toward Smoking Cessation Intervention, Self-Efficacy for Smoking Cessation Intervention, and Intention to Deliver Smoking Intervention after Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samet, J.M. Tobacco smoking: The leading cause of preventable disease worldwide. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2013, 23, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics. 2020 Cause of Death Statistical Results; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti, A.; Papadakis, S.; Schoretsaniti, S.; Rovina, N.; Vivilaki, V.; Gratziou, C.; Katsaounou, P. Smoking cessation in pregnancy: An update for maternity care practitioners. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2019, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, Y.; Soulakova, J.N. Retrospective reports of former smokers: Receiving doctor’s advice to quit smoking and using behavioral interventions for smoking cessation in the United States. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 11, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Song, M.S.; Kim, N.E. Establishment of the National Five Year Health Planning; Korea Health Promotion Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.R.; Oh, P.J. Barriers to smoking cessation intervention among clinical nurses. J. Korean Acad. Adult Nurs. 2005, 17, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, E.; Van der Kleij, R.M.J.J.; Chavannes, N.H. Facilitating smoking cessation in patients who smoke: A large-scale cross-sectional comparison of fourteen groups of healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, A.; Garcia, T.J.; Peck, J.; Sefcik, E. Occupational health nurses’ self-efficacy in smoking cessation interventions: An integrative review of the literature. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-H. Toolbox of teaching strategies in nurse education. Chin. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, A.A.; Page, K. Podcasts and videostreaming: Useful tools to facilitate learning of pathophysiology in undergraduate nurse education? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2009, 9, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.B. The impact of web-based video lectures on learning in nursing education: An integrative review. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2018, 39, E16–E20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, H.; Oprescu, F.I.; Downer, T.; Phillips, N.M.; McTier, L.; Lord, B.; Barr, N.; Alla, K.; Bright, P.; Dayton, J.; et al. Use of videos to support teaching and learning of clinical skills in nursing education: A review. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 42, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.-H.; Jeong, I.-J. The effects of role playing on empathy and communication competence for nursing students in psychiatric mental health nursing practicum. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2019, 13, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelis, A.; Cervello, S.; Rey, R.; Llorca, G.; Lambert, P.; Franck, N.; Dupeyron, A.; Delpont, M.; Rolland, B. Peer role-play for training communication skills in medical students: A systematic review. Simul. Healthc. 2020, 15, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagacean, C.; Cousin, I.; Ubertini, A.-H.; Idrissi, M.E.Y.E.; Bordron, A.; Mercadie, L.; Garcia, L.C.; Ianotto, J.-C.; De Vries, P.; Berthou, C. Simulated patient and role play methodologies for communication skills and empathy training of undergraduate medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-Y.; Park, H.-K.; Hwang, H.-S. Group randomized trial of teaching tobacco-cessation counseling to senior medical students: A peer role-play module versus a standardized patient module. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, K.; Cho, S. Effects of Education Program of Smoking Prevention and Cessation through the Linkages between Subjects of College Students in Some Area. Korean Soc. Sch. Community Health Educ. 2020, 21, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, L.; Oyefeso, A.; Annan, J.; Perryman, K.; Bloor, R.; Freeman, S.; Wain, B.; Andrews, H.; Grimmer, M.; Crisp, A.; et al. A survey of staff attitudes to smoking-related policy and intervention in psychiatric and general health care settings. J. Public Health 2006, 28, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-H. Factors affecting intention of smoking cessation intervention among nursing students. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2018, 18, 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, M.; Ahn, Y.; Park, H.; Lee, M. Simulation-based smoking cessation intervention education for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.H. Factors Affecting Psychiatric Nurses’ Intention to Implement Smoking Cessation Intervention; Department of Nursing, The Graduate School, Pukyong National University: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Segaar, D.; Willemsen, M.C.; Bolman, C.; De Vries, H. Nurse adherence to a minimal-contact smoking cessation intervention on cardiac wards. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiClemente, C.C.; Prochaska, J.O.; Fairhurst, S.K.; Velicer, W.F.; Velasquez, M.M.; Rossi, J.S. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-B. Association with smoking behavior, environmental factors and health promoting lifestyle among Korean university students. Korean J. Health Educ. Promot. 2015, 32, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Korean Women’s Development Institute. Current Smoking Rates (by Sex/Age); Korean Women’s Development Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S. The experiences of smoking and non-smoking in male adolescents. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2019, 20, 489–500. [Google Scholar]

- Paavola, M.; Vartiainen, E.; Haukkala, A. Smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity: A 13-year longitudinal study ranging from adolescence into adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2004, 35, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, T.V.; Clark, E.; Rowe, K. Undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes towards smoking health promotion. Nurs. Health Sci. 2005, 7, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jdani, S.; Mashabi, S.; Alsaywid, B.; Zahrani, A. Smoking cessation counseling: Knowledge, attitude and practices of primary healthcare providers at National Guard Primary Healthcare Centers, Western Region, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2018, 25, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Shishani, K.; Stevens, K.; Dotson, J.; Riebe, C. Improving nursing students’ knowledge using online education and simulation to help smokers quit. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuong, W.; Larsen, E.R.; Armstrong, A.W. Videos to influence: A systematic review of effectiveness of video-based education in modifying health behaviors. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drokow, E.K.; Effah, C.Y.; Agboyibor, C.; Sasu, E.; Amponsem-Boateng, C.; Akpabla, G.S.; Ahmed, H.A.W.; Sun, K. The impact of video-based educational interventions on cervical cancer, pap smear and HPV vaccines. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 681319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauerer, E.; Tiedemann, E.; Polak, T.; Simmenroth, A. Can smoking cessation be taught online? A prospective study comparing e-learning and role-playing in medical education. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2021, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.L.K.; Li, W.H.C.; Cheung, A.T.; Xia, W. Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions for smokers with chronic diseases: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3331–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Gharibi, K.A.; Schmidt, N.; Arulappan, J. Effect of repeated simulation experience on perceived self-efficacy among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 106, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.S.; Kim, S.H. Relationship between empathy ability, communication self-efficacy, and problem-solving process of nursing students who participated in simulation education applying role-play based on cases of schizophrenic patients. J. Learn.-Centered Curric. Instr. 2022, 22, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priambodo, A.P.; Nurhamsyah, D.; Lai, W.-S.; Chen, H.-M. Simulation-based education promoting situation awareness in undergraduate nursing students: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 65, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, F.J.; Heath, J.; Crowell, N. Using the Rx for Change tobacco curriculum in advanced practice nursing education. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. 2006, 18, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, N.A.; Kruse, G.R.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Treatment of tobacco smoking: A review. JAMA 2022, 327, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Stage of Change | Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Precontemplation | A 55-year-old man visiting a health checkup center. High blood pressure, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels in hypertensive patients who are not interested in smoking cessation. |

| 2 | Precontemplation | A 36-year-old woman goes to a gynecology outpatient clinic for a prescription for oral contraceptives that she has been taking for the past 5 years. She is planning to become pregnant in the near future but is not yet ready and smokes half a pack of cigarettes a day, but does not believe her smoking habit will adversely affect her health. |

| 3 | Contemplation | A 56-year-old man presents to the outpatient department for shortness of breath and cough. The patient only knows that he should quit smoking because his wife is strongly encouraging him to do so. |

| 4 | Contemplation | A 38-year-old firefighter who visits a health center smoking cessation clinic and wants to discuss using a nicotine patch to reduce his tobacco use. |

| 5 | Contemplation | A 29-year-old woman who is flirting with her boyfriend and wants her non-smoker boyfriend to know about her smoking habits. There is the thought of quitting smoking and the lack of mental preparation. |

| 6 | Preparation | A 52-year-old man with a past history of essential hypertension. Has just moved from abroad due to a job promotion and needs to stop smoking immediately. His blood pressure is around 140/90 and is slightly overweight for his height (about 5 kg overweight). |

| 7 | Relapse | A 60-year-old man with a thrombosis in a right leg vein. Has been taking wafarin for 5 years and was admitted to hospital 1 year ago with shortness of breath and hypertension. Smoked about one pack of cigarettes per day for 30 years prior to admission, but has been smoke-free for about 1 year using nicotine patches on the recommendation of his physician and relapsed 2 weeks ago. |

| Variables | Characteristics | Exp. 1 (n = 23) | Exp. 2 (n = 22) | Exp. 3 (n = 22) | χ2 or t(F) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or M (S) ± SD | n (%) or M (S) ± SD | n (%) or M (S) ± SD | ||||

| Sex | Male | 3 (25.0) | 5 (41.7) | 4 (33.3) | 0.72 | .675 |

| Female | 20 (36.4) | 17 (30.9) | 18 (32.7) | |||

| Age | 23.67 ± 3.09 | 144.32 | .837 | |||

| Grade (GPA) | 2.5–3.0 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3.73 | .753 |

| 3.0–3.5 | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | 8 (50.0) | |||

| 3.5–4.0 | 12 (38.7) | 12 (38.7) | 7 (22.6) | |||

| 4.0–4.5 | 6 (35.3) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) | |||

| Smoking status | Smoker | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) | 0.67 | .902 |

| Non-smoker | 19 (32.8) | 20 (34.5) | 19 (32.8) | |||

| Residence | With Smoker | 7 (43.8) | 5 (31.3) | 4 (25.0) | 0.96 | .678 |

| Without Smoker | 16 (31.4) | 17 (33.3) | 18 (35.3) | |||

| Attitude toward smoking cessation intervention | 25.74 ± 4.30 | 28.27 ± 5.24 | 26.86 ± 4.64 | 1.61 | .207 | |

| Self-efficacy for smoking cessation intervention | 32.22 ± 7.51 | 34.77 ± 8.86 | 32.27 ± 6.24 | 0.82 | .447 | |

| Intention to deliver smoking cessation intervention | 10.39 ± 2.31 | 11.41 ± 2.89 | 10.64 ± 2.40 | 0.98 | .383 | |

| Variables | Characteristics | n (%) or M ± SD | Attitude toward Smoking Cessation Intervention | Self-Efficacy for Smoking Cessation Intervention | Intention to Deliver Smoking Cessation Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t/F(p) | t/F(p) | t/F(p) | |||

| Sex | Male | 12 (17.9) | 0.71 (.479) | −0.08 (.937) | −0.71 (.481) |

| Female | 55 (82.1) | ||||

| Age | 23.67 ± 3.09 | 144.32 (.837) | 233.31 (.352) | 97.71 (.271) | |

| Grade | 2.5–3.0 | 3 (4.5) | 0.17 (.915) | 0.72 (.543) | 0.23 (.875) |

| 3.0–3.5 | 16 (23.9) | ||||

| 3.5–4.0 | 31 (46.3) | ||||

| 4.0–4.5 | 17 (25.4) | ||||

| Smoking status | Smoker | 9 (13.4) | 1.32 (.193) | 0.82(.414) | 0.36 (.720) |

| Non-smoker | 58 (86.6) | ||||

| Residence | With Smoker | 16 (23.9) | −1.21 (.232) | 0.22 (.828) | −1.00 (.320) |

| Without Smoker | 51 (67.1) | ||||

| Variables | Pre-Test | Post-Test | t | p | Source | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M ± SD) | (M ± SD) | |||||||

| Attitude toward smoking cessation intervention | Exp group 1. (n = 23) | 25.74 ± 4.30 | 27.09 ± 3.59 | −1.56 | .134 | T | 12.34 | <.001 |

| Exp group 2. (n = 22) | 28.27 ± 5.24 | 29.86 ± 3.43 | −2.48 | .021 | G | 4.66 | .013 | |

| Exp group 3. (n = 22) | 26.86 ± 4.64 | 30.68 ± 3.33 | −2.69 | .013 | T × G | 1.50 | .232 | |

| Paired-difference analysis | 26.94 ± 4.78 | 29.18 ± 3.74 | −3.47 | .001 | ||||

| Self-efficacy for smoking cessation intervention | Exp group 1. (n = 23) | 32.22 ± 7.51 | 35.39 ± 4.57 | −1.42 | .170 | T | 11.86 | <.001 |

| Exp group 2. (n = 22) | 34.77 ± 8.86 | 37.64 ± 5.87 | −2.06 | .052 | G | 1.32 | .276 | |

| Exp group 3. (n = 22) | 32.27 ± 6.24 | 35.86 ± 5.85 | −1.16 | .260 | T × G | 0.05 | .951 | |

| Paired-difference analysis | 33.07 ± 7.59 | 36.28 ± 5.45 | −3.49 | .001 | ||||

| Intention to deliver smoking cessation intervention | Exp group 1. (n = 23) | 10.39 ± 2.31 | 11.61 ± 2.06 | −5.54 | <.001 | T | 14.26 | <.001 |

| Exp group 2. (n = 22) | 11.41 ± 2.89 | 12.27 ± 2.03 | −2.83 | .010 | G | 1.12 | .334 | |

| Exp group 3. (n = 22) | 10.64 ± 2.40 | 12.27 ± 2.12 | −3.50 | .002 | T × G | 0.46 | .636 | |

| Paired-difference analysis | 10.81 ± 2.54 | 12.04 ± 2.06 | −3.81 | <.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, S.-R.; Lee, E.-H. Effects of a Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program on Nursing Students. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202734

Shin S-R, Lee E-H. Effects of a Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program on Nursing Students. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202734

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Sung-Rae, and Eun-Hye Lee. 2023. "Effects of a Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program on Nursing Students" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202734

APA StyleShin, S.-R., & Lee, E.-H. (2023). Effects of a Smoking Cessation Counseling Education Program on Nursing Students. Healthcare, 11(20), 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202734