Primary Care Disease Management for Venous Leg Ulceration in German Healthcare: Results of the Ulcus Cruris Care Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

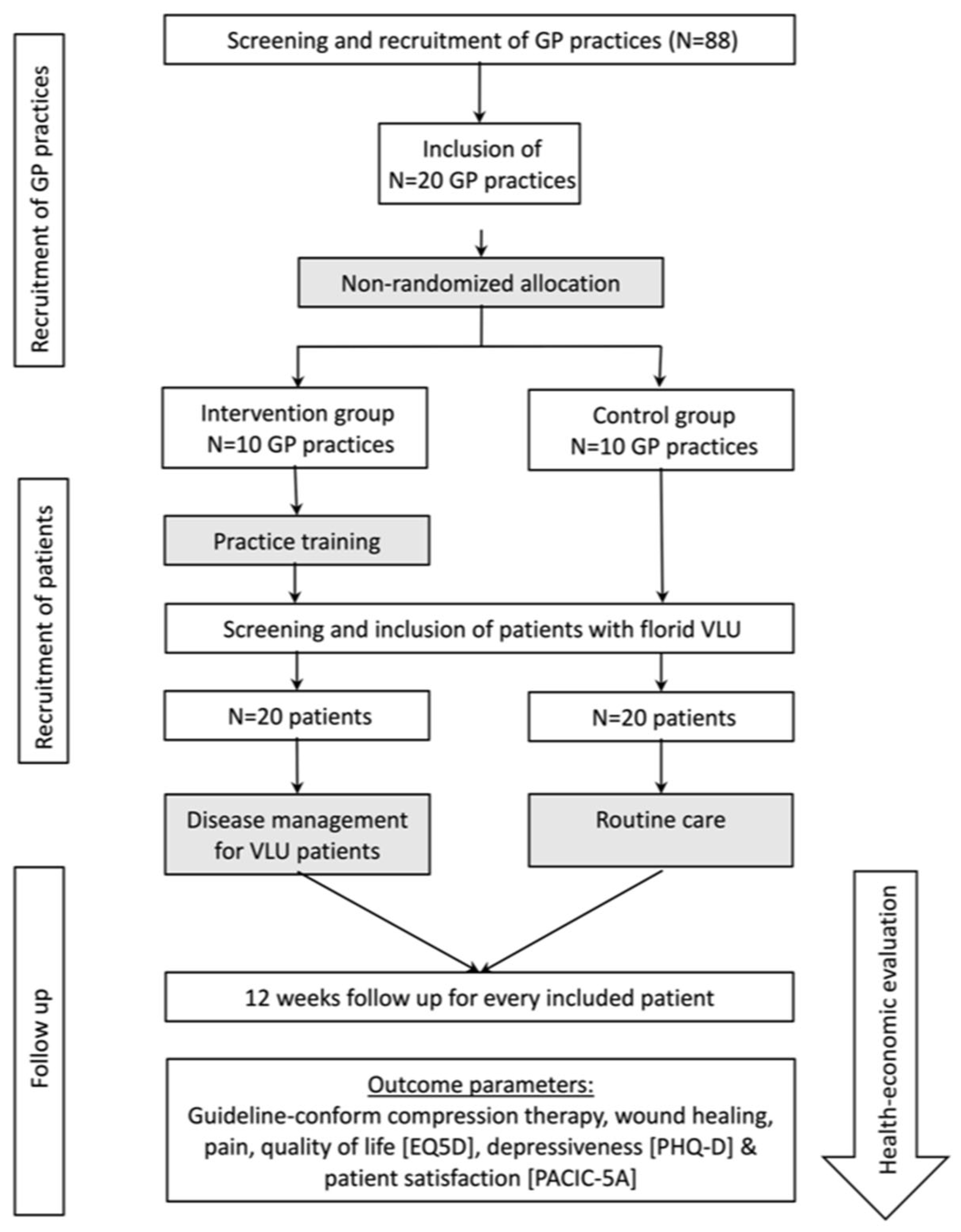

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Intervention

- a.

- Online team training for GPs and Health Care Assistants

- b.

- Software support for case management

- c.

- Educational material and e-learning for patients

2.4. Outcome Parameters

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Recruitment and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Use of Guideline-Conform Compression Therapy

3.3. Wound Healing

3.4. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Adherence

3.5. Health Economic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Control group |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| GP | general practitioner |

| HR QoL | health-related quality of life |

| IG | Intervention group |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| UCC | Ulcus Cruris Care |

| VAS | visual analogue scale |

| VLU | venous leg ulceration |

References

- Singer, A.J.; Tassiopoulos, A.; Kirsner, R.S. Evaluation and Management of Lower-Extremity Ulcers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopata, M.; Kucharzewski, M.; Tomaszewska, E. Antisecings in the treatment of venous leg ulcers: Clinical and microbiological aspects. J. Wound Care 2016, 25, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G.; Westby, M.J.; Rithalia, A.D.; Stubbs, N.; Soares, M.O.; Dumville, J.C. Dressings and topical agents for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 6, Cd012583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLain, N.E.M.; Moore, Z.E.H.; Avsar, P. Wound cleansing for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD011675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mościcka, P.; Cwajda-Białasik, J.; Jawień, A.; Sopata, M.; Szewczyk, M.T. Occurrence and Severity of Pain in Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers: A 12-Week Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidler, S.K.; Douillet, C.D.; Berndt, D.F.; Keagy, B.A.; Rich, P.B.; Marston, W.A. Inflammatory cytokine levels in chronic venous insufficiency ulcer tissue before and after compression therapy. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 49, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, S.; Cullum, N.; Nelson, E.A.; Dumville, J.C. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, CD000265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Dumville, J.C.; Cullum, N.; Connaughton, E.; Norman, G. Compression bandages or stockings versus no compression for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, Cd013397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, K.; Protz, K.; Glaeske, G.; Augustin, M. Epidemiology and use of compression treatment in venous leg ulcers: Nationwide claims data analysis in Germany: Compression treatment in venous leg ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2017, 14, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaby, G.; Senet, P.; Ganry, O.; Caudron, A.; Thuillier, D.; Debure, C.; Meaume, S.; Truchetet, F.; Combemale, P.; Skowron, F.; et al. Prognostic factors associated with healing of venous leg ulcers: A multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, K.; Protz, K.; Augustin, M. Compression therapy—Cross-sectional observational survey about knowledge and practical treatment of specialised and non-specialised nurses and therapists. Int. Wound J. 2017, 14, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protz, K.; Heyer, K.; Dörler, M.; Stücker, M.; Hampel-Kalthoff, C.; Augustin, M. Compression therapy: Scientific background and practical applications. JDDG J. Der Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2014, 12, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protz, K.; Dissemond, J.; Karbe, D.; Augustin, M.; Klein, T.M. Increasing competence in compression therapy for venous leg ulcers through training and exercise measured by a newly developed score-Results of a randomised controlled intervention study. Wound Repair Regen. 2021, 29, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauck, K.F.; Asi, N.; Elraiyah, T.A.; Undavalli, C.; Nabhan, M.; Altayar, O.; Sonbol, M.B.; Prokop, L.J.; Murad, M.H. Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of compression modalities for the promotion of venous ulcer healing and reducing ulcer recurrence. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 71S–90S.e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, C.D.; Buchbinder, R.; Johnston, R.V. Interventions for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 3, CD008378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossert, J.; Vey, J.A.; Piskorski, L.; Fleischhauer, T.; Awounvo, S.; Szecsenyi, J.; Senft, J. Effect of educational interventions on wound healing in patients with venous leg ulceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Wound J. 2023, 20, 1784–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protz, K.; Heyer, K.; Dissemond, J.; Temme, B.; Münter, K.C.; Verheyen-Cronau, I.; Klose, K.; Hampel-Kalthoff, C.; Augustin, M. Compression therapy—Current practice of care: Level of knowledge in patients with venous leg ulcers. JDDG J. Der Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2016, 14, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, M.; Mayer, A.; Goepel, L.M.; Baade, K.; Heyer, K.; Herberger, K. Cumulative Life Course Impairment (CLCI): A new concept to characterize persistent patient burden in chronic wounds. Wound Med. 2013, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, H. Does leg ulcer treatment improve patients’ quality of life? J. Wound Care 2004, 13, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimouguet, C.; Le Goff, M.; Thiébaut, R.; Dartigues, J.F.; Helmer, C. Effectiveness of disease-management programs for improving diabetes care: A meta-analysis. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. L’association Medicale Can. 2011, 183, E115–E127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S.; Taylor, S.J. Disease management interventions for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, Cd002752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruis, A.L.; Smidt, N.; Assendelft, W.J.; Gussekloo, J.; Boland, M.R.; Rutten-van Mölken, M. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, Cd009437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poß-Doering, R.; Anders, C.; Fleischhauer, T.; Szecsenyi, J.; Senft, J.D. Exploring healthcare provider and patient perspectives on current outpatient care of venous leg ulcers and potential interventions to improve their treatment: A mixed methods study in the ulcus cruris care project. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szecsenyi, J. CareCockpit—Hausarztpraxis-basiertes Case Management [Internet]. Available online: https://www.carecockpit.org (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Mergenthal, K.; Beyer, M.; Gerlach, F.M.; Guethlin, C. Sharing Responsibilities within the General Practice Team—A Cross-Sectional Study of Task Delegation in Germany. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, E.; Földi, E.; Gerlach, H.; Jünger, M.; Lulay, G.; Miller, A.; Protz, K.; Reich-Schupke, S.; Schwarz, T.; Stücker, M.; et al. Medical compression therapy of the extremities with medical compression stockings (MCS), phlebological compression bandages (PCB), and medical adaptive compression systems (MAC): S2k guideline of the German Phlebology Society (DGP) in cooperation with the following professional associations: DDG, DGA, DGG, GDL, DGL, BVP. Der Hautarzt Z. Dermatol. Venerol. Verwandte Geb. 2021, 72 (Suppl. 2), 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- EQ-5D [Internet]. EuroQol. 2022. Available online: https://euroqol.org/ (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Gräfe, K.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W.; Löwe, B. Screening psychischer Störungen mit dem “Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D)”. Diagnostica 2004, 50, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemann, T.; Laux, G.; Droesemeyer, S.; Gensichen, J.; Szecsenyi, J. Evaluation of a culturally adapted German version of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC 5A) questionnaire in a sample of osteoarthritis patients. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2007, 13, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, J.O.; Brettschneider, C.; Seidl, H.; Bowles, D.; Holle, R.; Greiner, W.; König, H.H. [Calculation of standardised unit costs from a societal perspective for health economic evaluation]. Gesundheitswesen 2015, 77, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzneimitteldaten [Internet]. ifap Service-Institut für Ärzte und Apotheker GmbH. 2022. Available online: https://www.ifap.de/deu_de/arzneimitteldaten.html (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Gohel, M.S.; Heatley, F.; Liu, X.; Bradbury, A.; Bulbulia, R.; Cullum, N.; Epstein, D.M.; Nyamekye, I.; Poskitt, K.R.; Renton, S.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Early Endovenous Ablation in Venous Ulceration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2105–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jull, A.; Slark, J.; Parsons, J. Prescribed Exercise with Compression vs Compression Alone in Treating Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Physician-diagnosed, confirmed VLU | Peripheral arterial occlusive disease of affected lower extremity with ABPI < 0.5 or ancle artery pressure < 50 mmHg |

| Age ≥ 18 years | Age < 18 years |

| Pyoderma gangraenosum | |

| Diabetic foot syndrome | |

| No capacity to consent |

| Intervention (n = 20) | Control (n = 20) | Total (n = 40) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 7 (35%) | 10 (50%) | 17 (42%) | 0.337 |

| Age | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 76.5 (62.0–86.0) | 77.5 (69.5–82.5) | 77.0 (67.5–84.0) | 0.807 |

| Ulcer duration [months] | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.5 (1.0–8.5) | 4.5 (1.5–24.0) | 4.5 (1.0–9.0) | 0.275 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.5–5.0) | 3.0 (2.5–4.0) | 4.0 (2.5–5.0) | 0.423 |

| Wound size [cm2] | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.5 (1.0–7.0) | 1.0 (1.0–10.0) | 2.5 (1.0–7.5) | 0.804 |

| Pain (VAS) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.5–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 3.0 (1.5–5.5) | 0.167 |

| Depressiveness (PHQ-9) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.5 (2.5–6.0) | 5.0 (1.5–7.0) | 5.0 (2.0–6.0) | 0.892 |

| Quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (47.5–72.5) | 72.5 (55.0–95.5) | 67.5 (50.0–82.5) | 0.043 * |

| Outcome | Intervention (T2) n = 20 | Control (T2) n = 19 | p-Value * | 95%-CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain (VAS) | 1.79 ± 2.15 | 1.74 ± 1.85 | 0.928 | [−1, 1] |

| Δ T2-Baseline | −1.21 ± 2.95 | −2.11 ± 2.56 | 0.393 | [−1, 2] |

| Depressiveness (PHQ-9) | 4.8 ± 5.2 | 3.5 ± 4.1 | 0.186 | [−1, 4] |

| Δ T2-Baseline | −0.85 ± 3.6 | −0.94 ± 2.4 | 0.652 | [−1, 2] |

| QoL score (EQ-5D-5L) | 70.3 ± 24.3 | 80.7 ± 21.4 | 0.166 | [−28, 2] |

| Δ T2-Baseline | 12.5 ± 18.3 | 9.7 ± 21.5 | 0.364 | [−5, 12] |

| QoL Index (EQ-5D-5L) | 0.71 ± 0.36 | 0.83 ± 0.26 | 0.297 | [−0.21, 0.053] |

| Δ T2-Baseline | 0.05 ± 0.19 | 0.11 ± 0.16 | 0.817 | [−0.12, 0.083] |

| Costs | Intervention | Control | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient care | EUR 172 ± 76 | EUR 155 ± 176 | 0.693 |

| EUR 7 ± 33 | EUR 5 ± 22 | 0.780 |

| EUR 164 ± 71 | EUR 142 ± 134 | 0.522 |

| Care services | EUR 498 ± 888 | EUR 378 ± 658 | 0.630 |

| Remedies | EUR 13 ± 34 | EUR 10 ± 28 | 0.804 |

| GP Prescriptions | EUR 697 ± 1.029 | EUR 1.506 ± 2.597 | 0.207 |

| EUR 223 ± 454 | EUR 647 ± 1.575 | 0.260 |

| EUR 276 ± 348 | EUR 625 ± 1.014 | 0.159 |

| Total costs | EUR 1.380 ± 1347 | EUR 2.049 ± 2.784 | 0.342 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senft, J.D.; Fleischhauer, T.; Poß-Doering, R.; Frasch, J.; Feißt, M.; Awounvo, S.; Müller-Bühl, U.; Altiner, A.; Szecsenyi, J.; Laux, G. Primary Care Disease Management for Venous Leg Ulceration in German Healthcare: Results of the Ulcus Cruris Care Pilot Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182521

Senft JD, Fleischhauer T, Poß-Doering R, Frasch J, Feißt M, Awounvo S, Müller-Bühl U, Altiner A, Szecsenyi J, Laux G. Primary Care Disease Management for Venous Leg Ulceration in German Healthcare: Results of the Ulcus Cruris Care Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182521

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenft, Jonas D., Thomas Fleischhauer, Regina Poß-Doering, Jona Frasch, Manuel Feißt, Sinclair Awounvo, Uwe Müller-Bühl, Attila Altiner, Joachim Szecsenyi, and Gunter Laux. 2023. "Primary Care Disease Management for Venous Leg Ulceration in German Healthcare: Results of the Ulcus Cruris Care Pilot Study" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182521

APA StyleSenft, J. D., Fleischhauer, T., Poß-Doering, R., Frasch, J., Feißt, M., Awounvo, S., Müller-Bühl, U., Altiner, A., Szecsenyi, J., & Laux, G. (2023). Primary Care Disease Management for Venous Leg Ulceration in German Healthcare: Results of the Ulcus Cruris Care Pilot Study. Healthcare, 11(18), 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182521