Experiencing (Shared) Decision Making: Results from a Qualitative Study of People with Mental Illness and Their Family Members

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants, Recruitment, and Setting

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

“To what extent do you talk about health information that you researched yourself with your doctor?”

“How do you experience the discussion about treatment options?”

“In your experience, how are decisions made about upcoming treatments? To what extent does this also apply to treatment decisions regarding your mental illness?”

“Where do you see options for improvement in how you can participate in treatment decisions? What would help you in the decision-making process?”

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Importance of Understanding the Origins of Mental Illness for SDM

“Everyone uses some kinds of compensation mechanisms in life. In some people they are more pronounced than in others. Some people have no compensation mechanisms worked out for certain issues, and the situation turns pathological or the burden is too heavy.”(B07)

“A person comes in with severe back problems, so you look at the big picture. […] to take a holistic approach and not just ‘I prod here and it hurts, therefore this is what I’ll be treating.’ You should instead look at the roots […] take time for the patient and then approach the problem holistically: ‘OK, this is what they do for a living. That could well be the cause.’ Even if it’s not obvious, you should also consider the role of the psyche.”(B04)

3.2. Relevance of Getting a Psychiatric Diagnosis on SDM

“The formulation back then […] was certainly better than today, because it only mentioned a ‘presence of symptoms’ rather than saying that ‘she has this or that illness.’ That is something I can live with much more easily, and probably other people could too […] But most people, they […] expect a diagnosis so they can say ‘how nice to have a name for it, something to call it.’”(B03)

“The general difficulty with diagnoses is that it’s hard, it’s very vague. I may have symptoms pointing to one illness and symptoms pointing to another. One doctor makes one diagnosis, another doctor makes a different diagnosis, and yet I remain the same person.”(B02)

“First of all, I find that mental illnesses still get pathologized. It is of course an illness but it also gets stigmatized a little. They won’t give you short-term or permanent disability insurance anymore.”(B07)

“I filled in a number of questionnaires with my therapist that were about grading or about finding out what areas of life I could still work on or where I might exhibit uncertainty, or what the areas were where I’d done a lot of work. […] I believe that everything that is under your control or that you can do yourself is also an opportunity to learn a lot about yourself.”(B04)

“What actually really annoys me is to keep hearing that one is ill. I was reading something recently that was making quite a bit of sense, but they used words like ‘the ill person’ or ‘the illness’ probably twenty times on every page. People keep zooming in on that without knowing the causes. You can see different doctors and get different diagnoses, even if you describe your situation very clearly. So, you shouldn’t harp on about ‘illness’.”(B02)

3.3. Importance of Stigma on Being Informed about Mental Illness and SDM

“To have heard it before would have helped me accept and be aware of how I was doing and what it might be that I had. And by that I don’t mean giving it a name, knowing that I have this thing called depression, but rather that it’s something you can get, just like a common cold. I believe it’s up to the educational system to legitimize and improve the understanding of these things, so that you’ve heard about it and you don’t have to feel ashamed of it.”(B04)

“There is a lot more information available about visible illnesses than there is about invisible ones. And when it comes to the invisible illnesses, there’s too much information on depression and too little on schizophrenia and psychoses. That, in my opinion, is the reason for the terrible notions people have: ‘A person with schizophrenia is likely to kill someone’.”(B13)

“Helplines exist, sure, but the hurdle of actually calling one of them is SO high, because I think in these cases many people still feel reluctant to accept help. Or they will feel very weak for seeking help. Or they can’t really get a handle on what’s going on in their minds, because the mind can’t get sick, after all. It’s just something you have to endure.”(B04)

“But it has not yet at all been understood that it’s actually good for you to face your illnesses head on. To face your problems head on. I mean, shouldn’t the fact that I’ve been to therapy actually be seen as a sign that I’m prepared to work on my problems.”(B07)

“I find it health education in schools VERY important, because there you’ll find the young adults and adolescents. And young people themselves have problems. They have no idea what’s going on with them at that moment or who they can turn to.”(B08)

“Ever since I’ve been able to deal with it openly, I’ve been extremely open about it with other people, including those who themselves are well, and I’ve talked about these illnesses. I tell people that I have depression and how that presents itself and how hard it is, too. And what happens when you have it, because without information it’s never going to gain acceptance in society. Otherwise you’ll always carry a social stigma, and something absolutely has to be done to fight that.”(B01)

3.4. Experiencing (Shared) Decision Making

“I’m really lucky to have a very good GP, with whom I get along very well on a personal level […], that I can confide in him and that I’ve felt like I am in good hands with him and he’s fortunately told me a great deal. And then later on through my therapist, who knew how to address everything very well and explained many things to me. Before that there was nothing at all.”(B04)

“I feel it’s important to have a basic understanding even before I see a doctor. So that I can also bring up my own ideas or wishes. Or demands, let’s say. I mean, to know what is possible and what you’re entitled to.”(B09)

“In hospitals, decision-making is very top-down, I mean totally top-down. You may perhaps state your opinion, but often you’re not taken seriously or at least that’s the impression you get. It can also happen that the doctor says: ‘well, there’s really only THIS and THIS and THIS, you are to take THESE drugs.’ What you often don’t have is time to think. […] You have to make your mind up there and then. Most often, there’s no time to sit down and think it through.”(B02)

“In my experience, professionals build up experience through spending a long time dealing with certain aspects of life to do with health. You cannot always grasp all that in its complexity by reading a set of guidelines or other texts. […] Frankly, I think that there are capabilities acquired through practical experience or training that can’t simply be substituted with ‘oh, I’ll take a couple of weeks and read up on the topic’.”(B07)

“Also, just to have the doctor explain why something is done, what is happening and why it’s happening. What is happening in the body? What is the effect, what is supposed to be the effect of a certain therapy? […] Simply to have something explained and cleared up in a one-on-one consultation is helpful. But that doesn’t always happen.”(B01)

“I always find it very helpful to have a plan like that. It gives you structure and support to know that, okay, ‘if this doesn’t help, there’s also this and there’s that.’ It just gives you a sense of security.”(B09)

“What I find important, above all, are different perspectives and that everything that can be done, I mean everything that is included in the guidelines and all the different avenues of treatment, that all of that is individually adapted to the patient’s needs. There should be no ‘the patient has to do this or that’, but instead the focus should be on the patient’s interests.”(B02)

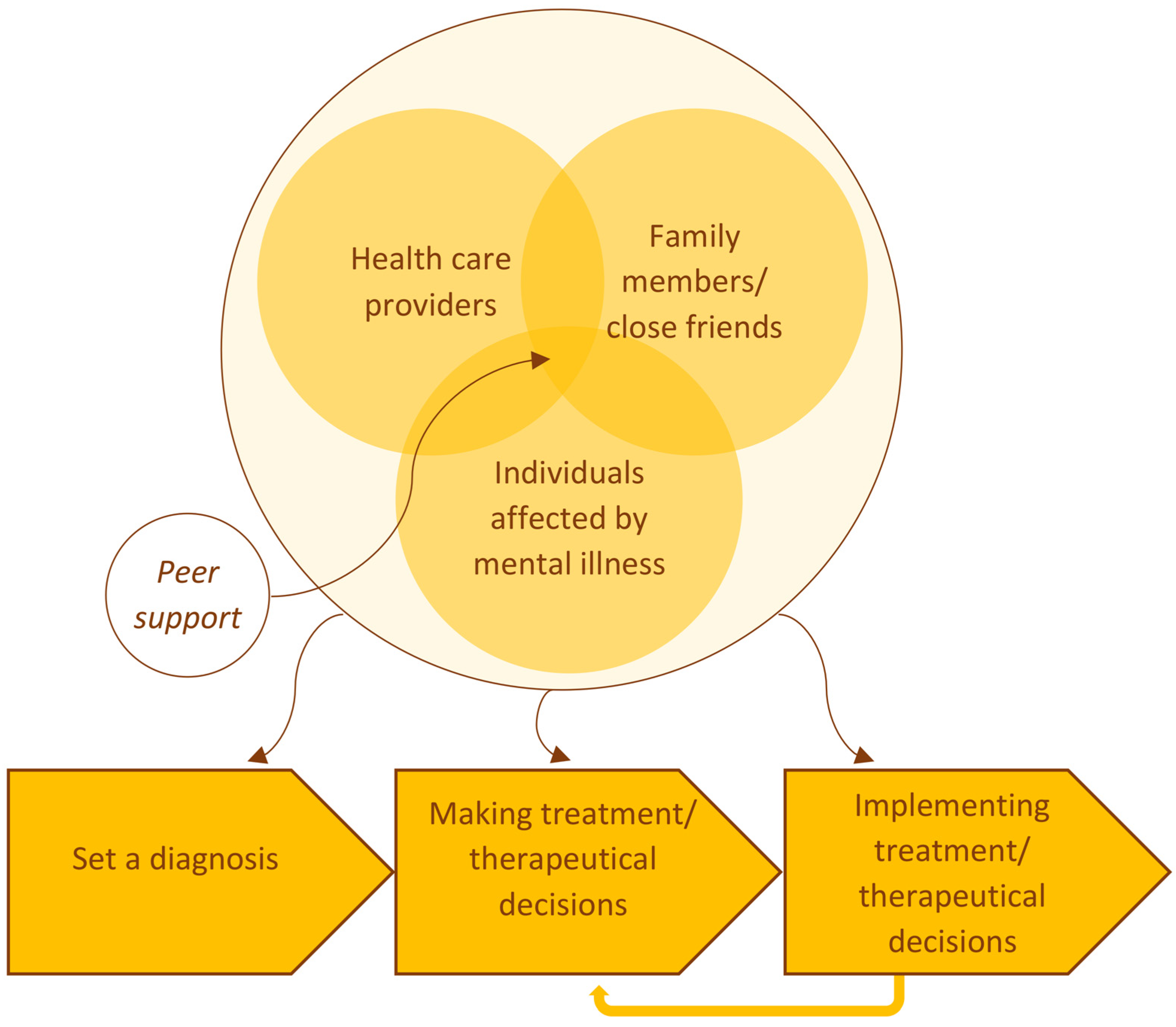

“Those are major topics when it’s time to make decisions. Therefore, it has to be all three. It’s best to involve family members, the affected person and specialists.”(B02)

3.5. Enabling and Hindering Structures to Implement Treatment Decisions

“The information provided by people who are affected is naturally something that, in combination with the information given by specialists, is particularly credible and useful. […] Also, the specialists who work together with people who are affected are often more trustworthy since they tend to have a different attitude. A patient of ours told me that once. She found it great that my boss hired me, as it says a lot about my boss that he would hire recovery companions. I believe she had a point.”(B10)

“On the other hand, I’ve had positive experiences at places like psychosocial contact and counseling centers because they don’t watch the clock. They really take the time to help you there. The interaction is more at eye level than it is with a doctor or a therapist.”(B02)

“Following the recommendation to find a therapist or see a specialist, for example. Even just reaching the right people. I mean, it’s nice to know that, under certain conditions, I should see a therapist. But if I can’t make an appointment or I have to go out of my way to see one, it’s an obstacle that I have to face.”(B07)

“You always get the feeling there’s not enough time. Everyone has to rush to make a diagnosis. The patient knows too that there are ten other patients waiting outside. When I see my therapist, she has exactly an hour for me and once my time is up, it’s over. I believe time is an important factor.”(B06)

“On the one hand, I think that if doctors, therapists and the rest of them, the support system, took more time to explain, and also to answer questions.”(B06)

“I can’t help it that the therapists are all booked up, and I know there’s nothing they can do other than keep on working. I get it. But it’s difficult knowing that you’ve got to wait three or six months for an appointment and not knowing how things are going to go for you in the meantime. And you’re going to be feeling bad in the meantime. So, there should be a place where you can get help at short notice and tips that can actively help you. What can I actually do in this situation? Even if it’s just relaxation techniques.”(B06)

3.6. Specific Needs of Individuals Affected by Mental Illness and Family Members Concerning SDM

“Someone from your private life to share the decision with you. […] If a doctor tells me to consider going on medication and I talk about it with a social education worker and we together decide that I ought to give it a try, the problem is that I’m left alone with the decision. […] If you have a family member going through this with you, I think it makes a difference.”(B02)

“Because, in my experience as a family member, I never felt truly involved and I never was really involved. […] I somehow find it absolutely relevant to include the relatives too. I find this approach is missing altogether.”(B07)

“My kids are now thirteen and eighteen. They are old enough to put two and two together. They have their points of view and ways of perceiving things. They can say: ‘What’s up with Dad, let’s help him, we’re old enough’.”(B14)

“I often find myself in a situation where I, as a family member, don’t feel I have the capacity to help. I believe that the problem lies deeper and that the person who is ill and their illness have to be dealt with more intensively. As a family member, I can be open to them, listen to them and so on. Coming up with recommendations is difficult though, maybe because I just don’t have the necessary knowledge. But above all, I’m no psychotherapist and it’s not something I’m able to do. I also don’t think it’s something that the relatives should be doing. […] I think an illness should be treated by professionals.”(B07)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary

4.2. Early Involvement of Individuals Affected by Mental Illness and Family Members—SDM as an Extended Process

4.3. Reducing the Knowledge Gap

4.4. Barriers of SDM Resulting from the Stigmatization of Mental Illness

4.5. Structural Barriers of SDM

4.6. Peer Support and Self-Help-Promoting SDM and Complementary Support Offers

4.7. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- In order to promote SDM, the knowledge gap between healthcare providers and individuals affected by mental illness and relatives should be reduced, e.g., by providing target group-tailored information and decision aids.

- Interventions should be developed and implemented which positively influence attitudes toward SDM in affected individuals, family members, and healthcare providers and which balance power in the treatment decision process, e.g., by low-level pre-consultation interventions.

- As stigmatization of mental illnesses is a significant barrier to SDM, destigmatization should be increased by implementing educational strategies and family engagement campaigns and disseminating media guidelines and evidence-based health information.

- Peer support, self-help associations, and psychosocial counseling services can promote empowerment and strengthen the recovery orientation. They should, therefore, be further strengthened within the healthcare system, advertised in information campaigns, and prominently referred to within health information.

- Complementary healthcare offers and e-mental health programs have the potential to empower and to spur action for recovery. Therefore, they should be made more accessible.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaba, R.; Sooriakumaran, P. The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship. Int. J. Surg. 2007, 5, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, K.; Rendtorff, J.D. Patient participation in mental health care–Perspectives of healthcare professionals: An integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krist, A.H.; Tong, S.T.; Aycock, R.A.; Longo, D.R. Engaging patients in decision-making and behavior change to promote prevention. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 240, 284–302. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner, C.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; Lohrmann, C.; Halfens, R.J.G.; Hahn, S. Conceptual understanding and applicability of shared decision-making in psychiatric care: An integrative review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, C.; Gschwendtner, K.; Müller, N.; Eich, W. Partizipative Entscheidungsfindung (PEF)–Patient und Arzt als Team. Rehabilitation 2017, 56, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, M.B.; Gooding, P.M. Spot the difference: Shared decision-making and supported decision-making in mental health. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2017, 34, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusty, W.T.; Penix, E.A.; Dimmick, A.A.; Swift, J.K. Shared decision-making in mental and behavioural health interventions. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2019, 25, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, K.; Rosenberg, D.; Svedberg, P.; Schön, U.-K. Shared decision-making in mental health care: A user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2016, 11, 30563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Whelan, T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buedo, P.; Luna, F. Shared decision making in mental health: A novel approach. Med. Etica 2021, 32, 1111–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making–Pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschner, B.; Becker, T.; Mayer, B.; Jordan, H.; Maj, M.; Fiorillo, A.; Égerházi, A.; Ivánka, T.; Munk-Jørgensen, P.; Krogsgaard Bording, M.; et al. Clinical decision making and outcome in the routine care of people with severe mental illness across Europe (CEDAR). Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2016, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, L.S.; Severinsson, E.; Hansen, B.S.; Rørtveit, K. Patients’ experiences of participating actively in Shared Decision-Making in mental care. J. Patient Exp. 2019, 6, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Petrie, K.; Harvey, S.B. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2119–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminskiy, E.; Zisman-Ilani, Y.; Ramon, S. Barriers and enablers to shared decision making in psychiatric medication management: A qualitative investigation of clinician and service users’ views. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 678005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriello, J. Patient-centered psychopharmacology and psychosocial interventions: Treatment selection and shared decision-making to enhance chances for recovery. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, MS19053BR4C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, S.; Zenter, N.; Ay, E.-S.; Loos, S.; Slade, M.; Corrado de, R.; Luciano, M.; Berecz, R.; Glaub, T.; Munk-Jørgensen, P.; et al. Clinical decision making and mental health service use among persons with severe mental illness across Europe. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, E.A.; Bond, G.R.; Drake, R.E. Economic approaches to improving access to evidence-based and recovery-oriented services for people with severe mental illness. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharoah, F.; Mari, J.; Rathbone, J.; Wong, W. Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, CD000088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Blanch, C.; Álvarez-Jiménez, M. Review: Family interventions reduce relapse or hospitalisation in people with schizophrenia. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2011, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, I.D.; Stekoll, A.H.; Hays, S. The role of the family and improvement in treatment maintenance, adherence, and outcome for schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 31, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.S.; Fernandez, P.A.; Lim, H.K. Family engagement as part of managing patients with mental illness in primary care. Singapore Med. J. 2021, 62, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, F.; Holzhüter, F.; Heres, S.; Hamann, J. ‘Triadic’ shared decision making in mental health: Experiences and expectations of service users, caregivers and clinicians in Germany. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Plummer, V.; Lam, L.; Cross, W. Perceptions of shared decision-making in severe mental illness: An integrative review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 27, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlqvist Jönsson, P.; Schön, U.-K.; Rosenberg, D.; Sandlund, M.; Svedberg, P. Service users’ experiences of participation in decision making in mental health services. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-García, V.; Rivero-Santana, A.; Duarte-Díaz, A.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Peñate-Castro, W.; Álvarez-Pérez, Y.; González-González, A.I.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Shared decision-making and information needs among people with generalized anxiety disorder. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doody, O.; Butler, M.P.; Lyons, R.; Newman, D. Families’ experiences of involvement in care planning in mental health services: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.; Green, D. Involved, inputting or informing: “Shared” decision making in adult mental health care. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, H.; Ramon, S. “Work with me”: Service users’ perspectives on shared decision making in mental health. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2017, 22, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashoorian, D.M.; Davidson, R.M. Shared decision making for psychiatric medication management: A summary of its uptake, barriers and facilitators. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Elwyn, G.; Edwards, A. Knowledge is not power for patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eassom, E.; Giacco, D.; Dirik, A.; Priebe, S. Implementing family involvement in the treatment of patients with psychosis: A systematic review of facilitating and hindering factors. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schladitz, K.; Weitzel, E.C.; Löbner, M.; Soltmann, B.; Jessen, F.; Schmitt, J.; Pfennig, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Gühne, U. Demands on health information and clinical practice guidelines for patients from the perspective of adults with mental illness and family members: A qualitative study with in-depth interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, A. Das problemzentrierte Interview. In Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie: Grundfragen, Verfahrensweisen, Anwendungsfelder; Jüttemann, G., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1985; pp. 227–255. ISBN 3-407-54680-7. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P.; Fenzl, T. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 633–648. ISBN 978-3-658-21307-7. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. (Eds.) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, Y. Shared decision making for adults with severe mental illness: A concept analysis. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitila, M.; Nummelin, J.; Kortteisto, T.; Pitkänen, A. Service users’ views regarding user involvement in mental health services: A qualitative study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheff, T.J. The labelling theory of mental illness. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Wassel, A. Understanding and influencing the stigma of mental illness. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2008, 46, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eads, R.; Lee, M.Y.; Liu, C.; Yates, N. The power of perception: Lived experiences with diagnostic labeling in mental health recovery without ongoing medication use. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossom, R.C.; Solberg, L.I.; Vazquez-Benitez, G.; Crain, A.L.; Beck, A.; Whitebird, R.; Glasgow, R.E. The effects of patient-centered depression care on patient satisfaction and depression remission. Fam. Pract. 2016, 33, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkai, P.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Döpfner, M. (Eds.) Diagnostisches und Statistisches Manual Psychischer Störungen DSM-5®; Korrigierte Auflage; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783801728038. [Google Scholar]

- Gühne, U.; Weinmann, S.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. S3-Leitlinie Psychosoziale Therapien bei Schweren Psychischen Erkrankungen: S3-Praxisleitlinien in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-662-58284-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tlach, L.; Wüsten, C.; Daubmann, A.; Liebherz, S.; Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J. Information and decision-making needs among people with mental disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 1856–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Biddle, C.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kaphingst, K.; Orom, H. Health literacy and use and trust in health information. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, E.S.; Krumholz, H.M.; Moulton, B.W. The new era of informed consent: Getting to a reasonable-patient standard through shared decision making. JAMA 2016, 315, 2063–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, W.W.; Aslani, P.; Chen, T.F. Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: A qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J. Interprof. Care 2013, 27, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, A.; Ellins, J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007, 335, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.B.; Brushe, M.; Elmes, A.; Polari, A.; Nelson, B.; Montague, A. Shared decision making with young people at ultra high risk of psychotic disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 683775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhnen, M.; Dreier, M.; Freuck, J.; Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J. Akzeptanz und Nutzung einer Website mit Gesundheitsinformationen zu psychischen Erkrankungen–www.psychenet.de. Psychiatr. Prax. 2022, 49, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabanciogullari, S.; Tel, H. Information needs, care difficulties, and coping strategies in families of people with mental illness. Neurosciences 2015, 20, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treichler, E.B.H.; Avila, A.; Evans, E.A.; Spaulding, W.D. Collaborative decision skills training: Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a novel intervention. Psychol. Serv. 2020, 17, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, S.; Street, R.L.; Barnes, D.E.; Shi, Y.; Volow, A.M.; Li, B.; Alexander, S.C.; Sudore, R.L. Empowering patients with the PREPARE advance care planning program results in reciprocal clinician communication. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.L.; Thornicroft, G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannin, D.G.; Vogel, D.L.; Brenner, R.E.; Abraham, W.T.; Heath, P.J. Does self-stigma reduce the probability of seeking mental health information? J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, D.; Babić, R.; Vasilj, I.; Avdibegović, E. Stigmatization of mentally ill patients through media. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 885–889. [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus, G.; Stolzenburg, S.; Freitag, S.; Speerforck, S.; Janowitz, D.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Muehlan, H.; Schmidt, S. Stigma as a barrier to recognizing personal mental illness and seeking help: A prospective study among untreated persons with mental illness. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 269, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, T.; Peter, L.-J.; Tomczyk, S.; Muehlan, H.; Schomerus, G.; Schmidt, S. The Seeking Mental Health Care model: Prediction of help-seeking for depressive symptoms by stigma and mental illness representations. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsfield, P.; Stolzenburg, S.; Hahm, S.; Tomczyk, S.; Muehlan, H.; Schmidt, S.; Schomerus, G. Self-labeling as having a mental or physical illness: The effects of stigma and implications for help-seeking. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, S.M.; Peterson, E.R.; Stephens, R.; Crandall, L.A. Stigma in mental health at the macro and micro levels: Implications for mental health consumers and professionals. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Druss, B.G.; Perlick, D.A. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2014, 15, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolzenburg, S.; Freitag, S.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Muehlan, H.; Schmidt, S.; Schomerus, G. The stigma of mental illness as a barrier to self labeling as having a mental illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Kostaki, E.; Kyriakopoulos, M. The stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, J.; Bühner, M.; Rüsch, N. Self-stigma and consumer participation in shared decision making in mental health services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, E.B.; Savoy, M.; Paranjape, A.; Washington, D.; Hackney, T.; Galis, D.; Zisman-Ilani, Y. Shared decision making in primary care based depression treatment: Communication and decision-making preferences among an underserved patient population. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 681165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, H. Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Glob. Ment. Health 2016, 3, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patafio, B.; Miller, P.; Baldwin, R.; Taylor, N.; Hyder, S. A systematic mapping review of interventions to improve adolescent mental health literacy, attitudes and behaviours. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1470–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freţian, A.M.; Graf, P.; Kirchhoff, S.; Glinphratum, G.; Bollweg, T.M.; Sauzet, O.; Bauer, U. The long-term effectiveness of interventions addressing mental health literacy and stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, B.S.; Fernandes, R.H.H.; Bobbili, S.J.; Ventura, C.A.A. Health care providers and people with mental illness: An integrative review on anti-stigma interventions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, T.; Knaak, S.; Szeto, A.C.H. Theoretical and practical considerations for combating mental illness stigma in health care. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, J.; Oudshoorn, A.; Anderson, K.; Marshall, C.A.; Stuart, H. Social contact: Next steps in an effective strategy to mitigate the stigma of mental illness. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; London, J.; Japhet, S.; Rüsch, N.; Flach, C.; Corker, E.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Mass social contact interventions and their effect on mental health related stigma and intended discrimination. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleman, M.; Regeer, B.J.; Schuitmaker-Warnaar, T.J. Shared decision-making and the nuances of clinical work: Concepts, barriers and opportunities for a dynamic model. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Shared Decision Making: NICE Guideline; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-4731-4145-2. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, K.; Schuster, F.; Rodolico, A.; Siafis, S.; Leucht, S.; Hamann, J. How should patient decision aids for schizophrenia treatment be designed? A scoping review. Schizophr. Res. 2023, 255, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallgren, K.A.; Bauer, A.M.; Atkins, D.C. Digital technology and clinical decision making in depression treatment: Current findings and future opportunities. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitger, T.; Korsbek, L.; Austin, S.F.; Petersen, L.; Nordentoft, M.; Hjorthøj, C. Digital shared decision-making interventions in mental healthcare: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 691251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, J.; Bärkås, A.; Blease, C.; Collins, L.; Hägglund, M.; Markham, S.; Hochwarter, S. Sharing clinical notes and electronic health records with people affected by mental health conditions: Scoping review. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e34170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2004, 27, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gühne, U.; Richter, D.; Breilmann, J.; Täumer, E.; Falkai, P.; Kilian, R.; Allgöwer, A.; Ajayi, K.; Baumgärtner, J.; Brieger, P.; et al. Genesungsbegleitung: Inanspruchnahme und Nutzenbewertung aus Betroffenenperspektive–Ergebnisse einer Beobachtungsstudie. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2021, 71, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Longden, E. Empirical evidence about recovery and mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Bryant, W. Peer support in adult mental health services: A metasynthesis of qualitative findings. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E. The mechanisms underpinning peer support: A literature review. J. Ment. Health 2019, 28, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gühne, U.; Weinmann, S.; Becker, T.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Das Recovery-orientierte Modell der psychosozialen Versorgung. Psychiatr. Prax. 2022, 49, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Yin, X.; Li, C.; Liu, W.; Sun, H. Stigma and peer-led interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 915617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Basu, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; English, C.L.; Newby, J.M. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 55, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.W.; McCloud, R.F.; Viswanath, K. Designing effective eHealth interventions for underserved groups: Five lessons from a decade of eHealth intervention design and deployment. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e25419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, R.F. Using evidence-based internet interventions to reduce health disparities worldwide. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehr, S.; Wittmann, F.; Jung, F.; Hoffmann, R.; Renner, A.; Dams, J.; Grochtdreis, T.; Kersting, A.; König, H.-H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Strategien zur Rekrutierung von Geflüchteten für Interventionsstudien: Erkenntnisse aus dem „Sanadak“-Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2019, 69, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.E.; Edwards, R. How Many Qualitative Interviews Is Enough: Expert Voices and Early Career Reflections on Sampling and Cases in Qualitative Research. Available online: https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/301922/how_many_interviews.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, N.; Blasius, J. (Eds.) Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-658-21307-7. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| 1 Importance of understanding the origins of mental illness for SDM | |

| 2 Relevance of getting a psychiatric diagnosis on SDM | |

| 3 Importance of stigma on informedness about mental illness and SDM | 3.1 Stigmatization |

| 3.2 Destigmatization | |

| 4 Experiencing (shared) decision making | 4.1 Past experiences |

| 4.2 Ideas for improving the decision-making process | |

| 5 Enabling and hindering structures to implement treatment decisions | 5.1 Good experiences |

| 5.2 Criticism | |

| 5.3 Ideas for improving | |

| 6 Specific needs of individuals affected by mental illness and family members concerning SDM | 6.1 Specific needs of affected persons |

| 6.2 Specific needs of family members |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schladitz, K.; Weitzel, E.C.; Löbner, M.; Soltmann, B.; Jessen, F.; Pfennig, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Gühne, U. Experiencing (Shared) Decision Making: Results from a Qualitative Study of People with Mental Illness and Their Family Members. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11162237

Schladitz K, Weitzel EC, Löbner M, Soltmann B, Jessen F, Pfennig A, Riedel-Heller SG, Gühne U. Experiencing (Shared) Decision Making: Results from a Qualitative Study of People with Mental Illness and Their Family Members. Healthcare. 2023; 11(16):2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11162237

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchladitz, Katja, Elena C. Weitzel, Margrit Löbner, Bettina Soltmann, Frank Jessen, Andrea Pfennig, Steffi G. Riedel-Heller, and Uta Gühne. 2023. "Experiencing (Shared) Decision Making: Results from a Qualitative Study of People with Mental Illness and Their Family Members" Healthcare 11, no. 16: 2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11162237

APA StyleSchladitz, K., Weitzel, E. C., Löbner, M., Soltmann, B., Jessen, F., Pfennig, A., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Gühne, U. (2023). Experiencing (Shared) Decision Making: Results from a Qualitative Study of People with Mental Illness and Their Family Members. Healthcare, 11(16), 2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11162237