Physician Engagement before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Questionnaire

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

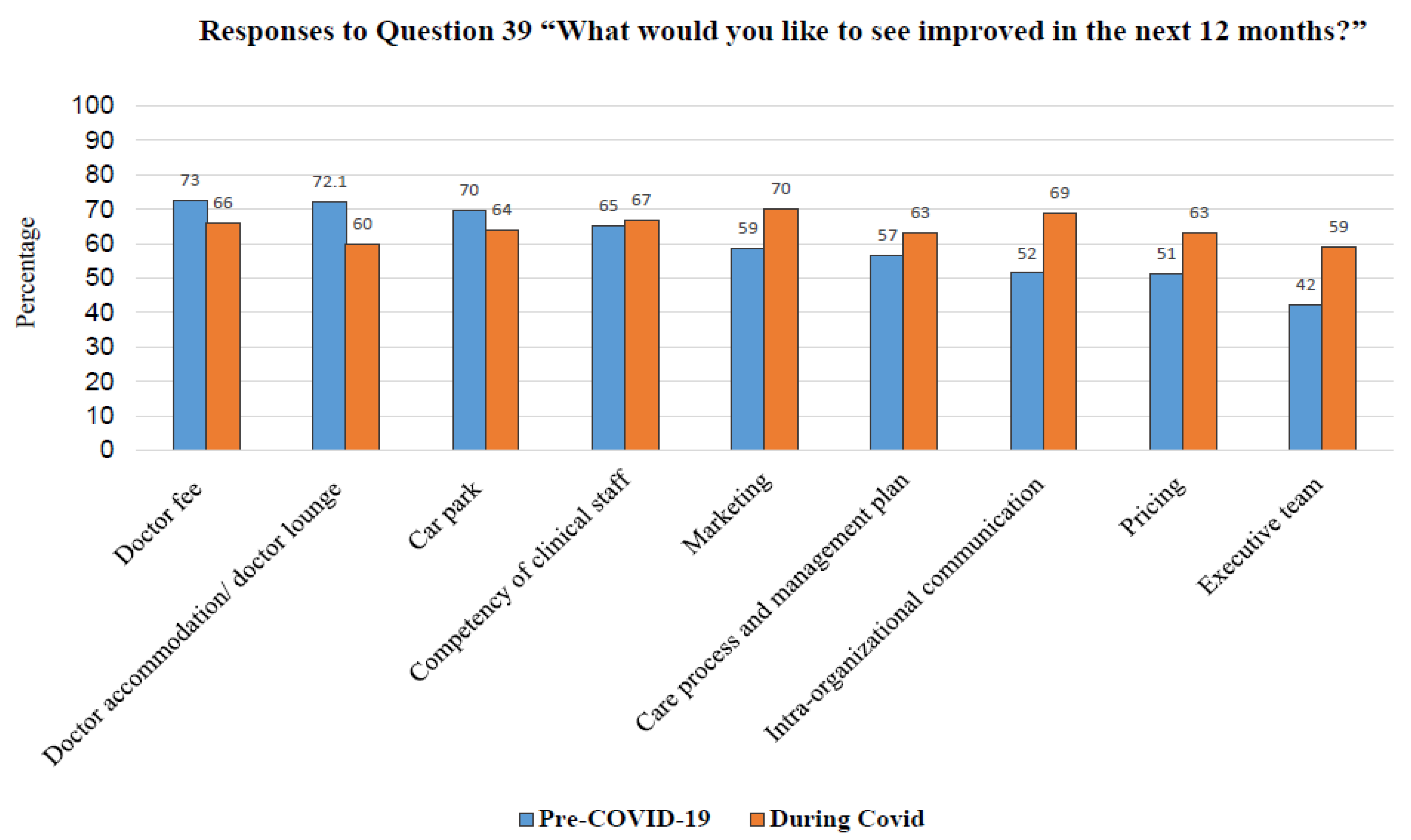

- Marketing: in addition to the government policy to implement an Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) clinic nationwide, the BDMS should highlight the newly introduced services to the public, such as the teleconsultation services, together with e-medical treatment, medication home delivery services, drive-through COVID-19 tests, etc.

- Intra- and inter-organizational communication: this is a crucial topic that needs to be addressed, especially regarding up-to-date information or even the professional standard-related incidence. Communication with doctors can be either official or unofficial and can take place through various channels. This physician recommendation is similar to the study of Matthew A Crain et al. [41].

- Competency of clinical staff: upskilling and reskilling of clinical staff working with physicians, e.g., nurses, should be consistently provided by the hospital. The organization needs to offer wide-ranging and easily accessible learning platforms, such as e-learning, in-house academic meetings, etc. Physicians also need to update their competencies during the uncertain and unpredictable COVID-19 situation. This recommendation aligns with other studies worldwide [26,42].

5. Limitations

6. Implications of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Diseases Control, Ministry of Public Health. COVID-19 Situation Report. Available online: https://ddc.moph.go.th/covid19-dashboard/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---29-december-2020 (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) WHO Thailand Situation Report 23. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/thailand/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-who-thailand-situation-report-234-4-may-2022-enth (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Perreira, T.A.; Perrier, L.; Prokopy, M.; Neves-Mera, L.; Persaud, D.D. Physician engagement: A concept analysis. J. Health Leadersh. 2019, 11, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradley, M.; Chahar, P. Burnout of healthcare providers during COVID-19. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2020, 89, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aryatno, R.M. The Relationship Between Work Engagement and Burnout in Ditpolair Korpolairud Baharkam Polri. Psychol. Res. Interv. 2019, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerstein, R.; Fux, C.A.; Vuichard-Gysin, D.; Abbas, M.; Marschall, J.; Balmelli, C.; Troillet, N.; Harbarth, S.; Schlegel, M.; Widmer, A.; et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by aerosols, the rational use of masks, and protection of healthcare workers from COVID-19. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.; Noble, S.; Johnston, S.; Jones, D.; Hunter, R. COVID-19 confessions: A qualitative exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID-19. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyashanu, M.; Pfende, F.; Ekpenyong, M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J. Interprof. Care 2020, 34, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardebili, M.E.; Naserbakht, M.; Bernstein, C.; Alazmani-Noodeh, F.; Hakimi, H.; Ranjbar, H. Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koontalay, A.; Suksatan, W.; Prabsangob, K.; Sadang, J.M. Healthcare Workers’ Burdens During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Health 2021, 14, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taitz, J.M.; Lee, T.H.; Sequist, T.D. A Framework for Engaging Physicians in Quality and Safety; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; Volume 21, pp. 722–728. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken, A.D. Physician engagement: A necessary but reciprocal process. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2014, 186, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spurgeon, P.; Mazelan, P.; Barwell, F. Medical engagement: A crucial underpinning to organizational performance. Health Serv. Manag. Res. Off. J. Assoc. Univ. Programs Health Adm. HSMC AUPHA 2011, 24, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreira, T.; Perrier, L.; Prokopy, M.; Jonker, A. Physician engagement in hospitals: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polit DF, B.C. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement With a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanthapornsak, S.; Manmart, L. The Factors Affecting Physicians’ Employee Engagement of Private Hospitals in the Northeastern Region, Thailand. KKU Res. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, S.; Roberts, R. Employee age and the impact on work engagement. Strat. HR Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungmala, N.; Verawat, A. The Impact of Socio-Demographic Factors on Employee Engagement at Multinational Companies in Thailand. J. Multidiscip. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 694–711. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P.W.; Loh, E.; Luong, K.; Worsley, K.; Tobin, A. Factors that influence and change medical engagement in Australian not for profit hospitals. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Palepu, A.; Dodek, P.; Salmon, A.; Leitch, H.; Ruzycki, S.; Townson, A.; Lacaille, D. Cross-sectional survey on physician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Vancouver, Canada: The role of gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Chen, J.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Dai, H.; Li, J.; Patty-Tito, R.M. Succumbing to the COVID-19 Pandemic—Healthcare Workers Not Satisfied and Intend to Leave Their Jobs. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 20, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.E.; Inbaraj, L.R.; Rajukutty, S.; De Witte, L.P. Challenges, experience and coping of health professionals in delivering healthcare in an urban slum in India during the first 40 days of COVID-19 crisis: A mixed method study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrente, M.; Sousa, P.A.; Sánchez-Ramos, A.; Pimentao, J.; Royuela, A.; Franco, F.; Collazo-Lorduy, A.; Menasalvas, E.; Provencio, M. To burn-out or not to burn-out: A cross-sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afulani, P.A.; Nutor, J.J.; Agbadi, P.; Gyamerah, A.O.; Musana, J.; Aborigo, R.A.; Odiase, O.; Getahun, M.; Ongeri, L.; Malechi, H.; et al. Job satisfaction among healthcare workers in Ghana and Kenya during the COVID-19 pandemic: Role of perceived preparedness, stress, and burnout. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2021, 1, e0000022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mache, S.; Vitzthum, K.; Klapp, B.F.; Danzer, G. Surgeons’ work engagement: Influencing factors and relations to job and life satisfaction. Surgeon 2014, 12, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algunmeeyn, A.; El-Dahiyat, F.; Altakhineh, M.M.; Azab, M.; Babar, Z.-U. Understanding the factors influencing healthcare providers’ burnout during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Jordanian hospitals. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longest, B.B.; Rakich, J.S.; Darr, K. Managing Health Services Organizations and Systems; Health Profession Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, X.-M.; Huang, X.-L.; Zhuang, X.-D.; Guo, P.; Feng, L.-F.; Hu, W.; Chen, L.; Hao, Y.-T. Job satisfaction and associated factors among healthcare staff: A cross-sectional study in Guangdong Province, China. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, F.; Hu, L.; Rakofsky, J.; Liu, T.; Wu, S.; Zhao, P.; Hu, G.; Wan, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Job Satisfaction of Psychiatrists in China: Results From the First Nationwide Survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nunez-Smith, M.; Pilgrim, N.; Wynia, M.; Desai, M.; Bright, C.; Krumholz, H.M.; Bradley, E.H. Health Care Workplace Discrimination and Physician Turnover. J. Natl. Med Assoc. 2009, 101, 1274–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crain, M.A.; Bush, A.L.; Hayanga, H.; Boyle, A.; Unger, M.; Ellison, M.; Ellison, P. Healthcare Leadership in the COVID-19 Pandemic: From Innovative Preparation to Evolutionary Transformation. J. Health Leadersh. 2021, 13, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimanothip, P. Factors Influencing Physician Engagement in Private Hospital. Master’s Thesis, The College of Management, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Respondent Characteristics | Total (n = 10,746) | Before COVID-19 (n = 5294) | During COVID-19 (n = 5452) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital’s Region | Capital City (8 hospitals) | 1715 (16.0%) | 814 (15.4%) | 901 (16.5%) |

| Central (7 hospitals) | 2558 (23.8%) | 1288 (24.3%) | 1270 (23.3%) | |

| Western (5 hospitals) | 1111 (10.3%) | 508 (9.6%) | 603 (11.1%) | |

| North/Northeastern (7 hospitals) | 1378 (12.8%) | 675 (12.8%) | 703 (12.9%) | |

| Eastern (11 hospitals) | 2929 (27.3%) | 1478 (27.9%) | 1451 (26.6%) | |

| Southern (6 hospitals) | 1055 (9.8%) | 531 (10.1%) | 524 (9.6%) | |

| Gender | Male | 5409 (50.3%) | 2691 (50.8%) | 2718 (49.9%) |

| Female | 5337 (49.7%) | 2603 (49.2%) | 2734 (50.1%) | |

| Age Group | 20–30 years | 761 (7.1%) | 423 (8.0%) | 338 (6.2%) |

| 31–40 years | 5311 (49.4%) | 2557 (48.3%) | 2754 (50.5%) | |

| 41–50 years | 2564 (23.9%) | 1237 (23.4%) | 1327 (24.3%) | |

| 51–60 years | 1260 (11.7%) | 648 (12.2%) | 612 (11.2%) | |

| >60 years | 850 (7.9%) | 429 (8.1%) | 421 (7.7%) | |

| Years of Employment | 0–11 months | 1406 (13.1%) | 834 (15.8%) | 572 (10.5%) |

| 1–5 years | 4634 (43.1%) | 2070 (39.1%) | 2564 (47.0%) | |

| 6–10 years | 2261 (21.0%) | 1145 (21.6%) | 1116 (20.5%) | |

| 11–15 years | 1132 (10.5%) | 586 (11.1%) | 546 (10.0%) | |

| 16–20 years | 531 (4.9%) | 245 (4.6%) | 286 (5.2%) | |

| 21–25 years | 358 (3.3%) | 185 (3.5%) | 173 (3.2%) | |

| 26–30 years | 200 (1.9%) | 111 (2.1%) | 89 (1.6%) | |

| >30 years | 224 (2.1%) | 118 (2.2%) | 106 (1.9%) | |

| Physician Status | Full Time | 4652 (43.3%) | 2309 (43.6%) | 2343 (43.0%) |

| Part Time | 6094 (56.7%) | 2985 (56.4%) | 3109 (57.0%) | |

| Specialty Group | Medicine | 4531 (42.2%) | 2301 (43.5%) | 2230 (40.9%) |

| Surgery | 2969 (27.6%) | 1436 (27.1%) | 1533 (28.1%) | |

| Obstetrics | 696 (6.5%) | 342 (6.5%) | 354 (6.5%) | |

| Pediatrics | 1161 (10.8%) | 583 (11.0%) | 578 (10.6%) | |

| Radiology | 528 (4.9%) | 263 (4.9%) | 265 (4.9%) | |

| Dentistry | 755 (7.0%) | 326 (6.2%) | 429 (7.9%) | |

| General | 106 (1.0%) | 43 (0.8%) | 63 (1.2%) | |

| Job Position | Practice Only | 9668 (90.0%) | 4743 (89.6%) | 4925 (90.3%) |

| Director of Department | 442 (4.1%) | 239 (4.5%) | 203 (3.7%) | |

| Management | 331 (3.1%) | 174 (3.3%) | 157 (2.9%) | |

| Not Specified | 305 (2.8%) | 138 (2.6%) | 167 (3.1%) | |

| Study Variables | n | Physician Engagement Score | t/F | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | |||||

| Year of Survey | Before COVID-19 | 5294 | 4.06 ± 0.51 | t = −5.624 | <0.001 a |

| During COVID-19 | 5452 | 4.12 ± 0.54 | |||

| Hospital’s Region | Capital City (8 hospitals) | 1715 | 4.07 ± 0.52 | F = 32.919 | <0.001 b |

| Central (7 hospitals) | 2558 | 4.13 ± 0.51 | |||

| Western (5 hospitals) | 1111 | 4.02 ± 0.55 | |||

| North/Northeastern (7 hospitals) | 1378 | 4.22 ± 0.52 | |||

| Eastern (11 hospitals) | 2929 | 4.02 ± 0.54 | |||

| Southern (6 hospitals) | 1055 | 4.09 ± 0.50 | |||

| Gender | Male | 5409 | 4.12 ± 0.54 | t = 5.982 | <0.001 a |

| Female | 5337 | 4.06 ± 0.52 | |||

| Age Group | 20–30 years | 761 | 4.19 ± 0.53 | F = 23.217 | <0.001 b |

| 31–40 years | 5311 | 4.12 ± 0.53 | |||

| 41–50 years | 2564 | 4.04 ± 0.54 | |||

| 51–60 years | 1260 | 4.02 ± 0.52 | |||

| >60 years | 850 | 4.05 ± 0.49 | |||

| Years of Employment | 0–11 months | 1406 | 4.17 ± 0.50 | F = 21.869 | <0.001 b |

| 1–5 years | 4634 | 4.13 ± 0.52 | |||

| 6–10 years | 2261 | 4.05 ± 0.55 | |||

| 11–15 years | 1132 | 4.00 ± 0.54 | |||

| 16–20 years | 531 | 3.96 ± 0.55 | |||

| 21–25 years | 358 | 4.01 ± 0.46 | |||

| 26–30 years | 200 | 4.00 ± 0.52 | |||

| >30 years | 224 | 4.04 ± 0.53 | |||

| Physician Status | Full Time | 4652 | 3.98 ± 0.54 | t = −18.791 | <0.001 a |

| Part Time | 6094 | 4.17 ± 0.51 | |||

| Specialty Group | Medicine | 4531 | 4.10 ± 0.52 | F = 1.502 | 0.173 b |

| Surgery | 2969 | 4.07 ± 0.54 | |||

| Obstetrics | 696 | 4.09 ± 0.51 | |||

| Pediatrics | 1161 | 4.09 ± 0.53 | |||

| Radiology | 528 | 4.07 ± 0.51 | |||

| Dentistry | 755 | 4.07 ± 0.51 | |||

| General | 106 | 4.15 ± 0.62 | |||

| Job Position | Practice Only | 9668 | 4.08 ± 0.53 | F = 10.113 | <0.001 b |

| Director of Department | 442 | 4.07 ± 0.45 | |||

| Management | 331 | 4.07 ± 0.48 | |||

| Not Specified | 305 | 4.25 ± 0.61 | |||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | t | p-Value | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| (Constant) | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.740 | 0.460 | −0.003 | 0.007 | |

| Year of Survey (0 = Before COVID-19, 1 = During COVID-19) | 0.061 | 0.015 | 0.039 | 4.078 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.090 |

| Gender (0 = Male, 1 = Female) | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −1.287 | 0.198 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Status (0 = Full Time, 1 = Part Time) | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −1.830 | 0.067 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| Accessibility Score | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.096 | 168.260 | 0.000 | 0.081 | 0.083 |

| Facilities Score | 0.170 | 0.001 | 0.193 | 300.173 | 0.000 | 0.169 | 0.171 |

| Clinical Care Score | 0.302 | 0.001 | 0.320 | 428.396 | 0.000 | 0.301 | 0.304 |

| Communication Score | 0.139 | 0.001 | 0.164 | 214.801 | 0.000 | 0.138 | 0.141 |

| Management Score | 0.137 | 0.001 | 0.180 | 241.365 | 0.000 | 0.136 | 0.138 |

| Relationship Score | 0.169 | 0.001 | 0.204 | 322.978 | 0.000 | 0.168 | 0.170 |

| Hospital Region_ Capital | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −1.544 | 0.123 | −0.003 | 0.000 |

| Hospital Region_Central | 5.726 × 10−5 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.944 | −0.002 | 0.002 |

| Hospital Region_Western | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.002 | −3.018 | 0.003 | −0.005 | −0.001 |

| Hospital Region_North/Northern | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.845 | 0.397 | −0.003 | 0.001 |

| Hospital Group_Eastern | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −1.835 | 0.067 | −0.003 | 0.000 |

| Age Group 20–30 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.947 | 0.344 | −0.001 | 0.004 |

| Age Group 31–40 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.287 | 0.198 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Age Group 41–50 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.327 | 0.744 | −0.002 | 0.002 |

| Age Group 51–60 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.274 | 0.203 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Years of Employment < 1 year | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.701 | 0.483 | −0.005 | 0.002 |

| Years of Employment 1–5 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.211 | 0.833 | −0.003 | 0.004 |

| Years of Employment 6–10 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.59 | 0.953 | −0.003 | 0.003 |

| Years of Employment 11–15 | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.628 | 0.530 | −0.005 | 0.002 |

| Years of Employment 15–20 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.119 | 0.905 | −0.004 | 0.003 |

| Years of Employment 21–25 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.696 | 0.486 | −0.002 | 0.005 |

| Years of Employment 25–30 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.694 | 0.488 | −0.006 | 0.003 |

| Job Position_Practice Only | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.001 | =1.952 | 0.051 | −0.005 | 0.000 |

| Job Position_Director of Department | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −1.664 | 0.096 | −0.006 | 0.000 |

| Job Position_Management Only | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001 | =1.436 | 0.151 | −0.06 | 0.001 |

| Survey Topics | Engagement Score | Unadjusted Mean Diff (95% CI) | Adjusted Mean | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mean ± SD) | Diff (95% CI) | |||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | Lower | Upper | |||

| A: Accessibility | ||||||

| A1: Scheduling process responsive and appropriate | 4.21 ± 0.696 | 4.20 ± 0.714 | −0.010 | −0.037 | 0.017 | 0.476 |

| A2: Access to and availability of patient record | 4.09 ± 0.736 | 4.13 ± 0.739 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.056 | 0.049 |

| A3: Ambulatory services | 4.16 ± 0.689 | 4.20 ± 0.688 | 0.048 | 0.022 | 0.075 | <0.001 |

| F: Facilities | ||||||

| F4: On-call doctor accommodation | 3.92 ± 0.859 | 4.00 ± 0.831 | 0.091 | 0.055 | 0.127 | <0.001 |

| F5: Doctor lounge | 4.02 ± 0.801 | 4.10 ± 0.797 | 0.082 | 0.051 | 0.113 | <0.001 |

| F6: Medical examination room | 4.09 ± 0.733 | 4.16 ± 0.723 | 0.065 | 0.037 | 0.093 | <0.001 |

| F7: Operating room | 4.13 ± 0.682 | 4.24 ± 0.681 | 0.097 | 0.064 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| F8: Availability of preferred equipment | 4.04 ± 0.728 | 4.12 ± 0.735 | 0.074 | 0.046 | 0.101 | <0.001 |

| F9: Cleanliness of facilities | 4.21 ± 0.718 | 4.30 ± 0.744 | 0.085 | 0.058 | 0.112 | <0.001 |

| F10: Quality of food and cleanliness | 3.86 ± 0.841 | 3.93 ± 0.858 | 0.079 | 0.046 | 0.112 | <0.001 |

| C: Clinical care and support services | ||||||

| C11: On-call doctors are good | 4.00 ± 0.689 | 4.08 ± 0.689 | 0.077 | 0.048 | 0.106 | <0.001 |

| C12: Nursing service | 4.09 ± 0.690 | 4.14 ± 0.693 | 0.057 | 0.031 | 0.084 | <0.001 |

| C13: Pharmacy service | 4.20 ± 0.639 | 4.27 ± 0.638 | 0.073 | 0.049 | 0.098 | <0.001 |

| C14: Radiology service | 4.18 ± 0.626 | 4.25 ± 0.632 | 0.075 | 0.05 | 0.099 | <0.001 |

| C15: Laboratory service | 4.13 ± 0.643 | 4.19 ± 0.663 | 0.061 | 0.036 | 0.086 | <0.001 |

| C16: Information technology service | 3.98 ± 0.752 | 4.06 ± 0.745 | 0.078 | 0.049 | 0.107 | <0.001 |

| C17: Biomedical engineering service | 4.05 ± 0.677 | 4.13 ± 0.685 | 0.081 | 0.054 | 0.107 | <0.001 |

| C18: Reception service | 4.21 ± 0.634 | 4.27 ± 0.656 | 0.056 | 0.031 | 0.081 | <0.001 |

| C19: Referral center service | 4.09 ± 0.662 | 4.16 ± 0.664 | 0.069 | 0.042 | 0.097 | <0.001 |

| C20: Marketing service | 3.89 ± 0.815 | 3.95 ± 0.844 | 0.060 | 0.026 | 0.094 | <0.001 |

| C21: Accounting and finance service | 4.12 ± 0.664 | 4.15 ± 0.707 | 0.025 | −0.001 | 0.052 | 0.063 |

| C22: Teamwork among care team | 4.08 ± 0.722 | 4.14 ± 0.738 | 0.061 | 0.034 | 0.089 | <0.001 |

| Co: Communication and feedback | ||||||

| Co23: The ability of hospital staff to respond and accurately resolve issues. | 3.92 ± 0.726 | 4.00 ± 0.740 | 0.080 | 0.053 | 0.107 | <0.001 |

| Co24: I have the opportunity to review this hospital’s patient satisfaction data. | 3.88 ± 0.760 | 3.98 ± 0.758 | 0.100 | 0.069 | 0.130 | <0.001 |

| Co25: I am satisfied with the communication I receive from the clinical staff about my patients. | 4.01 ± 0.691 | 4.08 ± 0.708 | 0.070 | 0.044 | 0.097 | <0.001 |

| Co26: My orders are carried out to my satisfaction. | 4.06 ± 0.688 | 4.11 ± 0.723 | 0.053 | 0.026 | 0.079 | <0.001 |

| Co27: The hospital provides high-quality care and services. | 4.16 ± 0.682 | 4.21 ± 0.699 | 0.054 | 0.028 | 0.080 | <0.001 |

| M: Management and business | ||||||

| M28: Hospital information readily available to doctor. | 3.93 ± 0.742 | 4.01 ± 0.753 | 0.088 | 0.06 | 0.117 | <0.001 |

| M29: Hospital support and responsiveness to doctors’ needs. | 3.92 ± 0.788 | 3.98 ± 0.806 | 0.058 | 0.029 | 0.088 | <0.001 |

| M30: Opportunity for giving opinions in hospital work. | 3.85 ± 0.824 | 3.89 ± 0.857 | 0.051 | 0.018 | 0.084 | 0.002 |

| M31: Hospital provides continuing medical education for physicians to develop an excellent healthcare center. | 3.95 ± 0.806 | 4.03 ± 0.814 | 0.077 | 0.045 | 0.109 | <0.001 |

| M32: Overall, how satisfied are you with the management/running of the hospital? | 4.03 ± 0.738 | 4.08 ± 0.767 | 0.052 | 0.024 | 0.081 | <0.001 |

| R: Relationship with hospital and loyalty | ||||||

| R33: Hospital delivers on its promises. | 4.04 ± 0.730 | 4.03 ± 0.789 | −0.005 | −0.034 | 0.024 | 0.739 |

| R34: I am proud to work with the hospital and I am a part of this organization (dedication). | 4.24 ± 0.686 | 4.27 ± 0.705 | 0.038 | 0.012 | 0.064 | 0.005 |

| R35: Hospital treats me with respect. | 4.25 ± 0.727 | 4.27 ± 0.754 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.041 |

| R36: It is difficult to detach myself from my work (absorption). | 3.97 ± 0.792 | 3.96 ± 0.842 | −0.001 | −0.033 | 0.030 | 0.931 |

| R37: When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work (vigor). | 4.07 ± 0.732 | 4.14 ± 0.736 | 0.081 | 0.053 | 0.109 | <0.001 |

| R38: I would recommend other doctors to work with this hospital. | 4.13 ± 0.762 | 4.19 ± 0.782 | 0.061 | 0.032 | 0.090 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suppapitnarm, N.; Saengpattrachai, M. Physician Engagement before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Thailand. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081394

Suppapitnarm N, Saengpattrachai M. Physician Engagement before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Thailand. Healthcare. 2022; 10(8):1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081394

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuppapitnarm, Nantana, and Montri Saengpattrachai. 2022. "Physician Engagement before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Thailand" Healthcare 10, no. 8: 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081394

APA StyleSuppapitnarm, N., & Saengpattrachai, M. (2022). Physician Engagement before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Thailand. Healthcare, 10(8), 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081394