Introducing New Paths towards Public Primary Healthcare Services in Greece: Efforts for Scaling-Up Mental Healthcare Services Addressed to Older Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Current Status in Greece

3. Proposing a Reformation of the Existing Public Primary Health Care

3.1. Establishing Specialized Structures for Health Care Services

3.2. Organizing Training Sessions

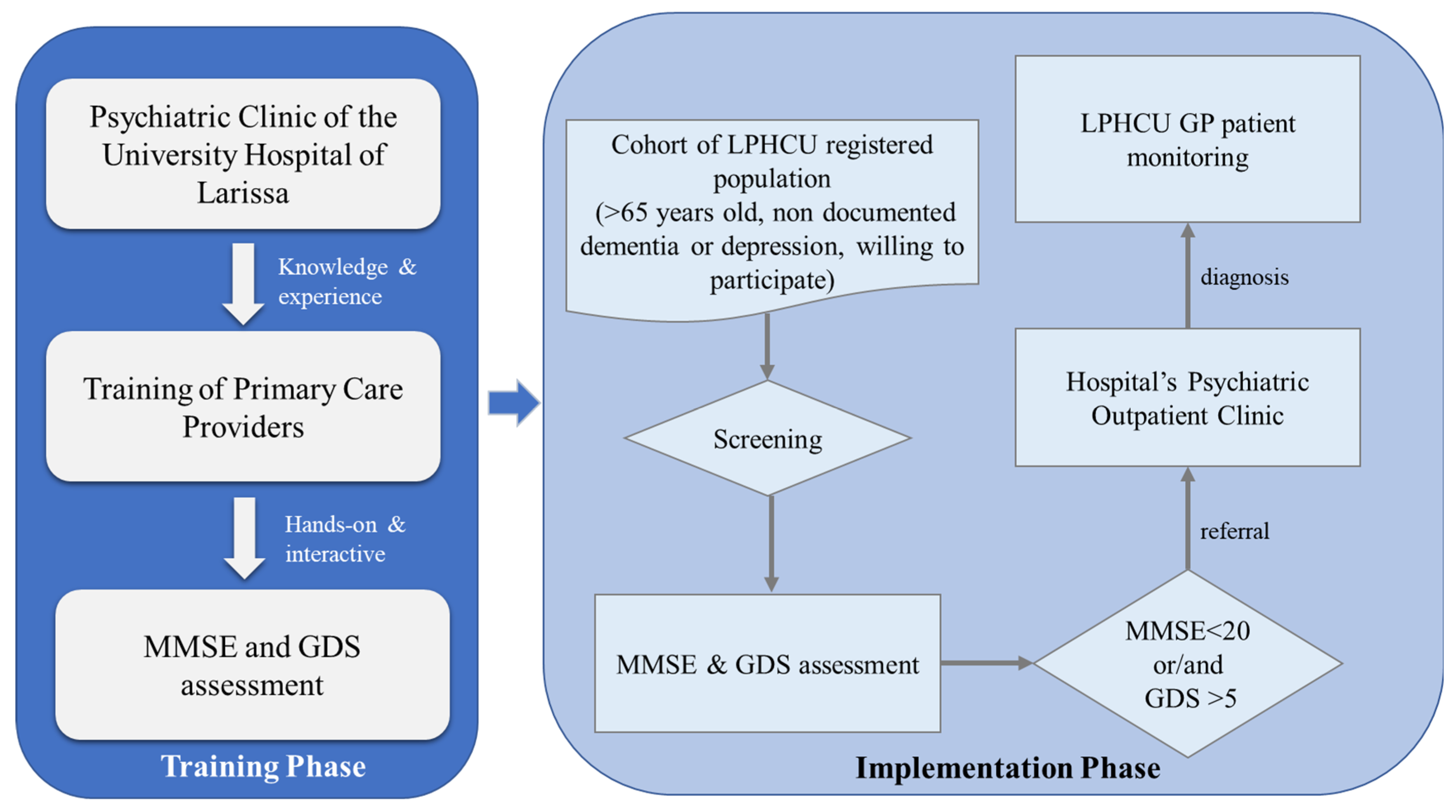

3.3. Focusing on Implementing a New Framework

4. Implication of Mental Health Care in Primary Health Care

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Sheldon, T.A.; Wright, J. Twin epidemics of COVID-19 and non-communicable disease. BMJ 2020, 369, m2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lazaro, C.I.; García-González, J.M.; Adams, D.P.; Fernandez-Lazaro, D.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Caballero-Garcia, A.; Racionero, F.M.; Córdova, A.; Miron-Canelo, J.A. Adherence to treatment and related factors among patients with chronic conditions in primary care: A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.A.; Reis, E.A.; Pinto, I.V.L.; Ceccato, M.D.G.B.; Silveira, M.R.; Lima, M.G.; Reis, A.M.M. Factors associated with the use of potentially inappropriate medications by older adults in primary health care: An analysis comparing AGS Beers, EU (7)-PIM List, and Brazilian Consensus PIM criteria. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031029 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Kenbubpha, K.; Higgins, I.; Chan, S.W.-C.; Wilson, A. Promoting active ageing in older people with mental disorders living in the community: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 24, e12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.D.S.S.C.B.; Souza, E.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.S.; Fett, C.A.; Piva, A.B. The effects of physical activity on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in elderly people living in the community. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019, 41, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, M.; Ara, M.A.; Gutiérrez, C.; Nolberto, V.; Piscoya, J. Depression and associated factors in the Peruvian elderly population according to ENDES 2014–2015. An. Fac. Med. 2018, 78, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025707 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Levav, I.; Rutz, W. The WHO World Health Report 2001 new understanding—New hope. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2002, 39, 50–56. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42390 (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- World Health Organization. The WHO Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. 2004. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241546468 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Lionis, C.; Symvoulakis, E.K.; Markaki, A.; Petelos, E.; Papadakis, S.; Sifaki-Pistolla, D.; Papadakakis, M.; Souliotis, K.; Tziraki, C. Integrated people-centred primary health care in Greece: Unravelling Ariadne’s thread. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotzamanis, B. The Population of Greece in the Horizon 2050, Promotion of Permanent Population, Population in the Different Tiers of Education, the Worker Population and Economically Active Population, 2015–2050 (Summary of Results). Laboratory of Demographic and Social Analysis, University of Thessaly. Available online: http://www.demography-lab.prd.uth.gr/About-en.asp (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Lima, C.A.; Ivbijaro, G. Mental health and wellbeing of older people: Opportunities and challenges. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2013, 10, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos, G.; Kelly, R., Jr. Geriatric mood disorders. In Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 9th ed.; Sadock, B.J., Sadock, V.A., Ruiz, P., Eds.; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 4047–4058. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou, M. The 2017 Primary Health Care (PHC) reform in Greece: Improving access despite economic and professional constraints? Health Policy 2021, 125, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringos, D.; Boerma, W.; Bourgueil, Y.; Cartier, T.; Dedeu, T.; Hasvold, T.; Hutchinson, A.; Lember, M.; Oleszczyk, M.; Pavlic, D.R.; et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: An international comparative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e742–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tierney, M.C.; Naglie, G.; Upshur, R.; Jaakkimainen, R.L.; Moineddin, R.; Charles, J.; Ganguli, M. Factors Associated with Primary Care Physicians’ Recognition of Cognitive Impairment in Their Older Patients. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2014, 28, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pezzotti, P.; Scalmana, S.; Mastromattei, A.; Di Lallo, D.; the “Progetto Alzheimer” Working Group. The accuracy of the MMSE in detecting cognitive impairment when administered by general practitioners: A prospective observational study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2008, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conradsson, M.; Rosendahl, E.; Littbrand, H.; Gustafson, Y.; Olofsson, B.; Lövheim, H. Usefulness of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15-item version among very old people with and without cognitive impairment. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Lixiouriotis, C. Mental Health Care Delivery for Adults in Rural Greece; Unmet Needs. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2019, 10, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, C.; Bell, A.; Baird, B.; Heller, A.; Gilburt, H. Mental Health and Primary Care Networks. Understanding the Opportunities; Centre for Mental Health, The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D.; Rabheru, K.; Ivbijaro, G.; de Mendonca Lima, C.A. Dignity of older persons with mental health conditions: Why should clinicians care? Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 774533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimou, C.; Harel, M.; Laubarie-Mouret, C.; Cardinaud, N.; Charenton-Blavignac, M.; Toumi, M.; Trimouillas, J.; Gayot, C.; Boyer, S.; Hebert, R.; et al. Patterns and predictive factors of loss of the independence trajectory among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.; Brown, L.; Hawley, M.; Astell, A. Older Adults’ Perspectives on Using Digital Technology to Maintain Good Mental Health: Interactive Group Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Salisbury, C. Relational continuity and patients’ perception of GP trust and respect: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e676–e683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Di Fava, A.; Vivas, C.; Marchionni, L.; Ferro, F. Smart and Healthy Ageing through People Engaging in Supportive Systems—H2020 SHAPES. Available online: https://shapes2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SHAPES-OC1-Enablers-Technical-Details.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Hopper, L.; Diaz-Orueta, U.; Konstantinidis, E.; Bamidis, P. Coach Assistant via Projected and Tangible Interface (CAPTAIN): Co-production of a Radically New Human Computer Interface with Older Adults. Age Ageing 2018, 47, v13–v60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mapanga, W.; Casteleijn, D.; Ramiah, C.; Odendaal, W.; Metu, Z.; Robertson, L.; Goudge, J. Strategies to strengthen the provision of mental health care at the primary care setting: An Evidence Map. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinaka, O.; Gioulekas, F.; Routa, E.; Delliou, A.; Stamatiadis, E.; Dratsiou, I.; Romanopoulou, E.; Billinis, C. Introducing New Paths towards Public Primary Healthcare Services in Greece: Efforts for Scaling-Up Mental Healthcare Services Addressed to Older Adults. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071230

Pinaka O, Gioulekas F, Routa E, Delliou A, Stamatiadis E, Dratsiou I, Romanopoulou E, Billinis C. Introducing New Paths towards Public Primary Healthcare Services in Greece: Efforts for Scaling-Up Mental Healthcare Services Addressed to Older Adults. Healthcare. 2022; 10(7):1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071230

Chicago/Turabian StylePinaka, Ourania, Fotios Gioulekas, Evlampia Routa, Aikaterini Delliou, Evangelos Stamatiadis, Ioanna Dratsiou, Evangelia Romanopoulou, and Charalambos Billinis. 2022. "Introducing New Paths towards Public Primary Healthcare Services in Greece: Efforts for Scaling-Up Mental Healthcare Services Addressed to Older Adults" Healthcare 10, no. 7: 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071230

APA StylePinaka, O., Gioulekas, F., Routa, E., Delliou, A., Stamatiadis, E., Dratsiou, I., Romanopoulou, E., & Billinis, C. (2022). Introducing New Paths towards Public Primary Healthcare Services in Greece: Efforts for Scaling-Up Mental Healthcare Services Addressed to Older Adults. Healthcare, 10(7), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071230