Abstract

(1) Introduction: The aim of our research was to explore emotional/behavioral changes in adolescents with neuropsychiatric conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, and parental stress levels through a standardized assessment, comparing the data collected before and during the first months of lockdown. Moreover, an additional goal was to detect a possible relationship between emotional/behavioural symptoms of adolescents and the stress levels of their parents. (2) Methods: We enrolled 178 Italian adolescents aged between 12–18 that were referred to the Child Neuropsychiatry Unit of the University Hospital of Salerno with different neuropsychiatric diagnoses. Two standardized questionnaires were provided to all parents for the assessment of parental stress (PSI-Parenting Stress Index-Short Form) and the emotional/behavioral problems of their children (Child Behaviour Check List). The data collected from questionnaires administered during the six months preceding the pandemic, as is our usual clinical practice, were compared to those recorded during the pandemic. (3) Results: The statistical comparison of PSI and CBCL scores before/during the pandemic showed a statistically significant increase in all subscales in the total sample. The correlation analysis highlighted a significant positive relationship between Parental Stress and Internalizing/Externalizing symptoms of adolescent patients. Age and gender did not significantly affect CBCL and PSI scores, while the type of diagnosis could affect behavioral symptoms and parental stress. (4) Conclusions: our study suggests that the lockdown and the containment measures adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic could have aggravated the emotional/behavioral symptoms of adolescents with neuropsychiatric disorders and the stress of their parents. Further studies should be conducted in order to monitor the evolution of these aspects over time.

1. Introduction

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the global pandemic status on 11 March 2020 [1] and many countries established national quarantine, there have been drastic changes in people’s lifestyles, perception of illness and social interaction [2].

The restrictions that were progressively adopted to contain the propagation of the virus in Italy, as in the rest of the world, caused negative effects on the psychological well-being of the general population [3,4,5,6].

Stressors due to the pandemic and quarantine-related issues have shown a negative influence on the mental well-being of both adults and young people [7,8].Children and adolescents experienced an unexpected and abrupt interruption in their everyday lives, including a prolonged stay in the home, altered relationship dynamics with their caregivers and family members, more infrequent interactions with peers, changed nutritional and lifestyle behaviors and other changes at the household level [9,10].

Children and adolescents appear to be more sensitive to the effects of COVID-19 than adults in developing internalizing and externalizing symptoms such as anxiety, depression, irritability and sleep problems [11,12,13,14,15].

The systematic review by Alamolhoda and colleagues [16] revealed an overall negative impact on the well-being of teenagers. The authors reported that the most frequent problems were increased levels of stress, anxiety symptoms, sleep difficulties, mood disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Petruzzelli and colleagues [17] highlighted a significant increase in psychiatric counseling in the Emergency Room in 2020–2022 compared to 2019, particularly for acute psychopathological symptoms in adolescent patients.

A study by Taylor et al. [18] found a significant increase in hair cortisol concentration in adolescents from pre- to post-lockdown of March 2020, which is robustly connected with neural dysfunction and consequent altered psychological well-being in the form of anxious and depressive symptoms.

In addition, the COVID-19 quarantine has been shown to impact the emotional well-being of young people with pre-existing neurological and psychiatric disabilities and their families, including increased levels of stress, anxiety and depression [19,20]. A piece of Italian research in 2021 conducted on a sample of patients with different neuropsychiatric disorders outlined a significant worsening in emotional/behavioral symptoms [21]. Another Italian study published in 2022, concerning children and adolescents with neuropsychiatric disorders, showed in the entire sample an aggravation as in internalizing as in externalizing symptoms during the lockdown period [22].

In the systematic review by Dal Pai et al. [23] the authors underlined that children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) experienced several pandemic-related issues that impacted their psychological well-being, behavior and sleep patterns. Another study that examined stress and anxiety levels in youth with and without ASD and their parents during the first three months of the pandemic, revealed that ASD families experienced more anxiety and stress [24].

The study by Theis et al. [25] on children with Intellectual Disabilities (ID) showed negative consequences on mental health, mood, behavior, social interaction and learning in most of the analyzed patients. Zhang et al. [26] underlined an aggravation of inattention and hyperactivity symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in children affected by Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), in addition to stress and mood alterations. The effects of the pandemic seem more severe in that part of the ADHD population which mostly uses the internet and electronic devices [27].A negative impact of the pandemic of emotional well-being was registered also in the pediatric population with epilepsy [28,29].

Finally, recent studies conducted on adolescents with [30,31,32,33,34,35,36] and without [37,38] neuropsychiatric disorders suggested a relationship between the emotional/behavioral symptoms of children and parental stress. Significant data were collected by Alhzumi [39] about children with ASD. Parental stress and emotional well-being of parents of children with ASD in Saudi Arabia had been unfavorably impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bitsika et al. [40] reported a raise in the risk of depression, anxiety and brooding thought in parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders; similarly, Willner et al. [41] noted heightened anxious and depressive traits and a sense of constraint in caregivers of children and adults with Intellectual Disabilities.

The review by Rohwerderat al. [42] highlights both the scarcity of literature and the importance of conducting research specifically on adolescents with disabilities in humanitarian emergencies, since the COVID-19 pandemic had adverse effects on adolescents with disabilities across health, education, livelihoods, social protection and community participation domains from those of non-disabled adolescents.

Furthermore, Shorey et al. [43] revealed in their literature review a lack of evidence-based studies and articles on children with other neurodevelopmental disorders apart from ASD and ADHD.

Based on this evidence, the main aim of our research is to describe the psychological, emotional and behavioral changes in Italian adolescents with different neuropsychiatric conditions before and during the first national lockdown and the effect on parental stress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Our study was conducted at the Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatric Unit of the San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggid’Aragona University Hospital in Salerno (Italy), a Complex Operative Unit for the diagnosis and pharmacological treatment of children and adolescents with neurological and psychiatric disorders (0–18 years).

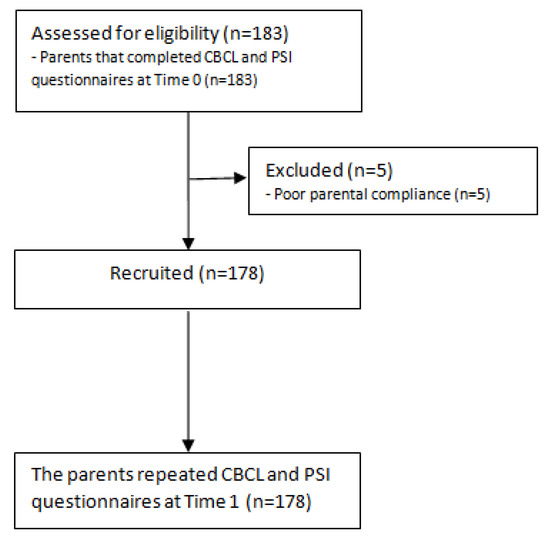

We enrolled all patients aged 12–18 who were referred to our Neuropsychiatry Unit in the months preceding the pandemic (September 2019–January 2020—Time 0) and whose parents had completed two standardized questionnaires for the assessment of emotional/behavioral symptoms (Child BehaviorCheckList6–18years, CBCL) and Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (PSI), as in our usual neuropsychological evaluations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of the research procedure. CBCL, Child Behavior Check List; PSI, Parenting Stress Index; Time 0 = September 2019–January 2020; Time 1 = March 2020–May 2020.

All the participants had a previous neuropsychiatric diagnosis, received in our unit between 2018–2019 by a multidisciplinary team (child neuropsychiatrists, speech therapists and child psychologists), based on DSM-5 criteria and supported by clinical observations and standardized neuropsychological tests.

The parents of all recruited patients were remotely contacted during the first lockdown (March–May 2020—Time 1) and were asked to repeat the CBCL and PSI questionnaires. A detailed explanation about the purpose and the procedures of the study was provided to all parents who sent their informed consent in writing form by e-mail afterwards. The only exclusion criterion was the poor compliance of the parents.

The parents who decided to participate in our study completed the questionnaires remotely, by different devices such as a smartphone or personal computer. Alternatively, the parents could fill out the questionnaires by e-mail or through an online program created for that specific purpose.

A team composed of six child psychologists and two child neuropsychiatrists analyzed the data collected during the lockdown. Subsequently, the data collected during the lockdown were compared with those collected before the pandemic.

In our analysis, we considered gender, age, diagnosis, comorbidities, drug therapy, age and level of education of the parents (years of education).

The study was approved by the Campania South Ethics Committee (protocol 61902) and followed the guidelines of good clinical practice.

2.2. Child Behavior Check List

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [44] is a standardized questionnaire that has been proven to be an effective way of assessing emotional/behavioral symptoms in children and adolescents aged between 6–18. The tool includes 113 statements and there are three possible options for each question: 2 = true or very true; 1 = sometimes true; 0 = false. The raw scores were converted into t-scores based on gender and age. The t-scores were distributed among 6 DSM-oriented subscales and 8 empirical subscales that can lead to obtain 3 main scales: Externalizing, Internalizing and Total Problems. We can interpret the t-score of all the subscales as follow: ≤64 = in the range of the norm; 65–69 = borderline; ≥70 pathological. Moreover, we can interpret the t-scores of the main scales based on the following interval: ≤59 = in the range of the norm; 60–64 = borderline; ≥65 pathological. Alpha reliability coefficient shave been noted to be ranged from 0.72–0.97. In addition, the test–retest reliability score was from 0.82–0.94.

2.3. ParentingStress Index

The Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) [45] is a standardized survey comprehending 36 questions with 5 possible answers for each. A score from 1 to 5 is assigned to each answer (1 = strongly disagree – 5 = strongly agree). Four scales emerged from this questionnaire: Parental Distress (PD), Parent–child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI), Difficult Child (DC) and Total Stress (TS).The raw score is converted to t-scores based on age; t-score ≥85 is considered clinically significant. The reliability coefficients were ≥0.96, showing a high internal consistency. Test–retest reliability score was 0.65–0.96.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We expressed all the neuropsychological scores as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We have preliminarily carried out an evaluation of the data distribution through the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test and we decided to employ non-parametric methods for our analysis, as many data did not meet the criteria of a normal distribution. For the comparison between mean scores before and during the pandemic, we used Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The possible relationship among different data was explored through the Spearman correlation test. We calculated the effect size using the two indicators η2 and r, interpreting them as follows: a value ≤ 0.3 represents a small effect size, a value between 0.4–0.7 represents a medium effect size, a value ≥ 0.8 represents a large effect size [46].Multivariate linear regression analysis and posthoc analysis were employed to evaluate the effect of some variables such as gender, age and type of diagnosis on CBCL and PSI scores. We considered statistically significant a p-value < 0.05.Statistical Package for Social Science software, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, 2015) was used for our statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

We recruited 183 families but five (2.7%) decided to not participate in our study. The total sample included 178 Caucasian adolescents and their families, aged between 12–18 years (mean age = 15.34 ± 2.17; male = 108, 61%) with the following neuropsychiatric diagnosis: epilepsy (n = 66; 37%), autism spectrum disorder (n = 26; 15%), specific learning disorders (n = 26; 15%), anxiety disorders (n = 15; 8%), intellectual disability (n = 13; 7%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (n = 11; 6%), behavioral disorders (n = 11; 6%), mood disorders (n = 10; 6%). The main socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of all the participants were summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Main socio-demographic feature of the total sample. SD = standard deviation. * calculated in years of education.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and clinical features of the subsample and total sample.

3.2. Mean Score Comparison of CBCL before/during the First Lockdown

The statistical comparison of the mean CBCL scores showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) at Time 1in all the scales (Anxiety/Depression, Withdrawal/Depression, Somatic complaints, Socialization, Thought problems, Attention problems, Rule-breaking behavior, Aggressive behavior, Affective problems, Anxiety problems, Somatic Problems, ADHD, Oppositional-defiant problems, Conduct problems, Internalizing problems, Externalizing problems, Total problems) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical comparison between mean scores of the Child Behavior Check List and the Parental Stress Index at time 0 (before the pandemic) and at Time 1 (March-May 2020). p-value < 0.05 are in bold. N = 178.

The effect size ranges from small to medium, according to the different scales, with a lower effect for the scale of Thought problems and a greater effect for the scales of Anxiety/Depression, Somatic complaints, Anxiety problems, Internalizing problems and Total problems (Table 3).

Analyzing the subsamples divided by diagnoses, we found that all the CBCL scales were significantly higher in adolescents with specific learning disorders, anxiety, behavioral disorder and epilepsy (p < 0.05).

In adolescents with Autism, we found a significant increase in all the CBCL scales (p < 0.05) except for pervasive problems (Z = −1.450, p = 0.147) and attention problems (Z = −1.851, p = 0.064). In the adolescents with intellectual disabilities all the CBCL scales were significantly higher at Time 1 except Thought problems (Z = −1.409, p = 0.159) and ADHD (Z = −1.691, p = 0.091). We did not find significant changes in the CBCL scales in the ADHD subsample, excepting for the Somatic complaints scale (Z = −2134, p = 0.033). In the adolescent with mood disorder all the CBCL subscales were significantly higher (p < 0.05) except for Thought problems (Z = −0.250, p = 0.803).

3.3. Mean Score Comparison of PSI before/during the First Lockdown

We found a statistically significant increase at Time 1 compared to Time 0 in all the mean scores of PSI (Parental Distress, Parent–child Difficult Interaction, Difficult Child, Total Stress) (Table 3). The effect size ranges from small to medium, with a lower effect for the Difficult Child scale and a greater effect for the Total stress scale (Table 3).

Analyzing the different subsamples divided by diagnosis emerged that all the PSI scales were significantly higher in patients with autism, ADHD, specific learning disorder, anxiety and behavioral disorder (p < 0.05).

All the PSI scales were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the epilepsy subsample except for Parent–child Dysfunctional Interaction scale (Z = −1.364, p = 0.173).All of the mean scores of PSI scales were significantly higher (p < 0.05)in the intellectual disability subpopulation except for Difficult Child (Z = −1.436, p = 0.151). We did not find significant changes in the PSI scales in the mood disorder group (p > 0.05).

3.4. Correlation Analysis between PSI and CBCL Scales

The correlation analysis showed a significant positive relationship between all the subscales of PSI (Parental Distress, Parent–child Difficult Interaction, Difficult Child and Total Stress) and the main scales of CBCL (Total problems, Externalizing problems, Internalizing problems). The strength was medium for all of the relationships analyzed. All the results of the correlation analysis are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation analysis between Child Behavior Checklist and Parental Stress Index subscales. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist. p-value < 0.05 are in bold.

3.5. Multivariate Linear Regression Analysis at Time 1

We performed multivariate linear regression analysis to investigate the effect of sex, age and diagnosis variables on CBCL and PSI scores at Time 1. We found that gender and age did not statistically significantly affect CBCL scores and PSI (Table 5), while the type of diagnosis has a statistically significant impact (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate linear regression analysis between at Time 1. p value < 0.05 are in bold.

The posthoc analysis of CBCL scores showed statistically significant differences, as follows: the Total problems scale was significantly lower in patients with epilepsy than in patients with autism spectrum disorder (p = 0.017) and behavioral disorders (p = 0.005); the Externalizing problems scale was significantly lower in patients with epilepsy than in patients with autism spectrum disorder (p = 0.008), anxiety disorder (p = 0.008), mood disorder (p = 0.013) and behavioral disorder (p < 0.001); the Internalizing problems scale was lower in patients with epilepsy than in patients with behavioral disorder, but did not reach the statistical significance (p = 0.068).

The posthoc analysis of PSI scores showed the following results: The Parental Distress scale (PD) was significantly lower in patients with epilepsy than in those with autism spectrum disorder (p = 0.003), anxiety disorder (p = 0.001), ADHD (p = 0.044), behavioral disorder(p = 0.017), and was significantly higher in patients with an anxiety disorder than in patients with a specific learning disorder (0.043). The Parent–child Dysfunctional Interaction scale (P-CDI) was significantly lower in patients with epilepsy than in those with autism spectrum disorder (p = 0.046) and anxiety disorder (p = 0.037). The Difficult Child (DC) was significantly lower in patients with epilepsy than in those with autism spectrum disorder (p = 0.021). The Total Stress scale (TS) was significantly lower in patients with epilepsy than in those with autism spectrum disorder (p = 0.005), anxiety disorder (p = 0.004) and behavioral disorder (p = 0.023).

4. Discussion

The aim of our research was to assess the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an Italian adolescent population with neurological and psychiatric disorders and parental stress, comparing the pre-pandemic period with the first month of lockdown.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, children and adolescents suffered from isolation, confinement, boredom and worries about their psychophysical health [47,48,49,50,51,52], with increased concerns in parents about their children’s well-being [53,54]. Families with children with special needs presented the most serious consequences of the lockdown [55]. It is important to underline the close relationship between the parents’ and children’s emotional status, with significant repercussions on the entire families’ psychological well-being. The experience of specific worries about their children’s mental well-being increases the risk of depression, brooding and anxiety in their parents’ well-being [56]. On the other hand, increased parental anxiety and worries were related to emotional dysregulation and internalizing and externalizing problems in their children during the pandemic [57].

Our sample included 178 Italian adolescents and their families (Table 1 and Table 2), aged between 12–18 years with the following neuropsychiatric diagnosis: epilepsy (n = 66), autism spectrum disorder (n = 26), specific learning disorders (n = 26), anxiety disorders (n = 15), intellectual disability (n = 13), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (n = 11), behavioral disorders (n = 11), mood disorders (n = 10). All the parents completed two standardized questionnaires for the assessment of emotional/behavioral symptoms of the adolescents (CBCL) and of parental stress (PSI) before/during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, our study showed a significant increase in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the whole sample during the lockdown, as reported by the parents. The statistical comparison before/during the lockdown showed a significant worsening in all scales of the CBCL, with a greater effect for the scales of Anxiety/Depression, Somatic complaints, Anxiety problems, Internalizing problems and Total problems. These findings suggest that internalizing problems, such as anxiety and somatic symptoms, had a greater impact in our sample.

Our results agree with a literature review by Guessoum et al., (2020) [13] that confirmed an increase in the symptomatology in adolescents with a psychiatric disorder, especially mood disorders, ADHD and autism spectrum disorder. Doyle and colleagues [58] detected a worsening in psychiatric symptoms of 171 youth outpatients (mean age aged 10.6 ± 3.1)during the school year following the first COVID-19 lockdown, including anxiety, oppositional behavior and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Conti et al. [21] registered a worsening of emotional and behavioral traits in 141 patients under the age of 18 (mean age = 10.6 ± 3.1 years) with neuropsychiatric disorders during the March 2020 lockdown. In addition, a tendency for a better reaction to the lockdown in psychiatric patients than the neurological disorders group has been suggested. Conversely, Raffagnato and colleagues [31] did not observe major changes during the lockdown compared to the previous period in a sample of children and adolescents with mental health disorders (n = 56; mean age = 13.4 ± 2.77 years). In particular, the authors concluded that the group of patients who previously suffered from internalizing disorders overall showed a good adaptation to the pandemic context, while a greater psychological discomfort was detected in patients with behavioral problems attributable to neurodevelopmental and conduct disorders. Finally, our results are at odds with those reported by De Giacomo et al. [35], which did not detect a worsening of the internalizing and externalizing CBCL symptoms in 71 children with neuropsychiatric disorders before and during the lockdown (average age 9.01 ± 3.67). This difference may be due to the different ages of our sample, which only considered adolescents.

Analyzing the subsamples divided by diagnoses, we found that the adolescents with anxiety disorder, mood disorder, specific learning disorder, behavioral disorder and epilepsy showed a global worsening in all the CBCL scales. In agreement with our data, previous literature studies had shown a worsening of psychological well-being during the lockdown in patients with epilepsy and learning disabilities [28,29,59,60,61] probably due to difficulties with distance learning; in contrast with our results, a larger sample study found that both depressive and anxiety symptoms were lower for adolescents with mood disorders during the pandemic compared to before [62].

In the subsample with Autism, we found a significant worsening of all the CBCL scales, except for pervasive problems and attention problems. In the adolescents with intellectual disabilities all the CBCL scales were significantly higher except for Thought problems and ADHD scales. Several previous studies confirmed a worsening in young people with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly represented by an increase in anxiety symptoms, irritability hyperactivity and behavioral problems [23,24,25,63], probably due to changes in their daily routines and access to therapies. Other studies, on the other hand, suggested a reduction in emotional behavioral manifestations in adolescents with autism due to lower social pressure [64].

In our study, surprisingly, we did not find significant changes in the CBCL scales in the ADHD subsample, except for the Somatic complaints scale. These results are in contrast with previous surveys [26,27]. Behrmann et al. [65] observed in adolescent patients diagnosed with ADHD, who experience depression, anxiety, loneliness, boredom and emotional distress. We can speculate that the lockdown hit differently children and adolescent’s psychological well-being, considering that only adolescent subjects have been observed in our analysis.

Analyzing the PSI scores we found a significant increase in parental stress during the lockdown in all the areas analyzed(Parental Distress, Parent–child Difficult Interaction, Difficult Child, Total Stress), with a lower effect for the Difficult Child scale and a greater effect for the Total stress scale. The feeling of having a complicated relationship with children was strongly heightened during the lockdown period, highlighting a greater perception of parental-role-related stress and total stress.

Analyzing the different subsamples that emerged, all the PSI scales were significantly higher in patients with autism, ADHD, specific learning disorder, anxiety and behavioral disorder. All the PSI scales were significantly higher in the epilepsy group except for Parent–child Dysfunctional Interaction scale. All the mean scores of PSI scales were significantly higher in the intellectual disability subpopulation, except for Difficult Child. The results of our study are in agreement with previous literature studies, which demonstrated increased parental stress in families with children and adolescents with neurological or psychiatric problems [66]. The study of De Giacomo et al. [35] highlights an increase in parental stress and a more difficult parent–child interaction in the period of lockdown due to the pandemic in a sample of children with neuropsychiatric conditions. Contrary to what we expected, we did not find significant changes in the PSI scales in parents of adolescents with mood disorders. We can hypothesize that internalizing symptoms, such as anxiety and mood disorders, could be hard to acknowledge and decipher; for this reason, these pathological states could worsen without being noticed.

The correlation analysis showed a significant relationship between parental stress and the internalizing/externalizing symptoms of adolescent patients. In this regard, it was shown that the resilience of the entire family has a mutual influence on mental well-being and the ability to successfully cope with changes, both in parents and children, resulting in stress and depression of children related to those of parents [37]. In agreement with our results, Costa et al. [67] suggest that this relationship could be due to parents’ dissatisfied expectations of their children or else to a non-reinforcing parent–child interaction. These data are supported also by the study by Sesso et al. [30] that, in a cross-sectional study on pediatric patients with neuropsychiatric conditions during Lockdown, found significant positive associations between CBCL Internalizing problems of and all PSI subscales, and between CBCL Externalizing problems and Difficult Child subscales.

The multivariate regression analysis in our sample highlighted that age and sex did not affect the emotional/behavioral symptoms and parental stress during the lockdown. On the contrary, the type of diagnosis could significantly affect both. More in detail, patients with epilepsy showed less emotional/behavioral problems, especially with regard to externalizing symptoms than adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder and behavioral disorder. Finally, parental stress levels were lower in the epilepsy group than in the groups diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, anxiety disorder, specific learning disorder, ADHD, and behavioral disorder. This finding suggests that emotional–behavioral symptoms may be more present in pediatric patients with psychiatric disorders than in patients with epilepsy during the COVID-19 lockdown. Similarly, although high levels of parental stress are documented in the parents of patients with different neuropsychiatric conditions [68,69,70,71], parents of adolescents with psychiatric disorders may experience higher levels of stress than those of adolescents with epilepsy.

The strength of the study was the use of standardized quantitative questionnaires and the focus on a specific population of patients (adolescents with neuropsychiatric disorders). The main limitation of our study is the small sample size, especially in some subgroups, which can reduce the statistical power. Other weaknesses of the study are the lack of a control group and the homogeneous geographical provenience of the participants. In future studies, we aim to analyze the emotional/behavioral symptoms of adolescents with neuropsychiatric disorders and parental stress over time (during and post the COVID-19 pandemic) and compare them with a control group. We aim to consider, in our future analysis, other socio-demographic and clinical variables than can affect psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Conclusions

Our research showed a significant worsening of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents with neuropsychiatric conditions during the first COVID-19 lockdown, which could suggest that confinement, social isolation, lifestyle changes and reduced access to therapy could impact the global psychological well-being in this population. Our study showed also an increase in parental stress, that was related to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms of the adolescent patients. We can suppose that the malaise in individual family members, in addition, to reiterate intra-familiar interactions, could have set up a vicious circle of parental stress and adolescents’ behavioral and emotional symptoms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F.O. and G.M.G.P.; methodology, C.S.A.; formal analysis, G.M.G.P. and A.L.; data curation, F.T.P., M.O. and L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.G.P. and F.T.P.; writing—review and editing, G.M.G.P. and G.S.; supervision, M.R. and M.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The procedure was approved by the Campania South Ethics Committee (protocol number n.0061902, approved on 20 April 2020) and was conducted according to the rules of good clinical practice, in line with the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the family who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Park, S.E. Epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; Coronavirus Disease-19). Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2020, 63, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanti, G.; Peter, N.; Tonia, T.; Holloway, A.; White, I.R.; Darwish, L.; Low, N.; Egger, M.; Haas, A.D.; Fazel, S.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Associated Control Measures on the Mental Health of the General Population: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ruiz, V.-R.; Alfaro-Navarro, J.L.; Huete-Alcocer, N.; Nevado-Peña, D. Psychological and Social Vulnerability in Spaniards’ Quality of Life in the Face of COVID-19: Age and Gender Results. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garagiola, E.R.; Lam, Q.; Wachsmuth, L.S.; Tan, T.Y.; Ghali, S.; Asafo, S.; Swarna, M. Adolescent Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Impact of the Pandemic on Developmental Milestones. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.-L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-being Among Children and Adolescents During the First COVID-19 Wave. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furstova, J.; Kascakova, N.; Sigmundova, D.; Zidkova, R.; Tavel, P.; Badura, P. Perceived stress of adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown: Bayesian multilevel modeling of the Czech HBSC lockdown survey. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 964313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Figueiredo, C.S.; Sandre, P.C.; Portugal, L.C.L.; M´azala-de-Oliveira, T.; da Silva Chagas, L.; Raony, Í.; Ferreira, E.S.; Giestal-de-Araujo, E.; dos Santos, A.A.; Bomfim, P.O.S. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessoum, S.B.; Lachal, J.; Radjack, R.; Carretier, E.; Minassian, S.; Benoit, L.; Moro, M.R. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherali, S.; Punjani, N.; Louie-Poon, S.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S. Mental Health of Children and Adolescents Amidst COVID-19 and Past Pandemics: A Rapid Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamolhoda, S.H.; Zare, E.; HakimZadeh, A.; Zalpour, A.; Vakili, F.; Chermahini, R.M.; Ebadifard, R.; Masoumi, M.; Khaleghi, N.; Nasiri, M. Adolescent mental health during COVID-19 pandemics: A systematic review. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, M.G.; Furente, F.; Colacicco, G.; Annecchini, F.; Margari, A.; Gabellone, A.; Margari, L.; Matera, E. Implication of COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescent Mental Health: An Analysis of the Psychiatric Counseling from the Emergency Room of an Italian University Hospital in the Years 2019–2021. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.K.; Fung, M.H.; Frenzel, M.R.; Johnson, H.J.; Willett, M.P.; Badura-Brack, A.S.; White, S.F.; Wilson, T.W. Increases in Circulating Cortisol during the COVID-19 Pandemic are Associated with Changes in Perceived Positive and Negative Affect among Adolescents. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzi, E.; Galli, J. New clinical needs and strategies for care in children with neurodisability during COVID-19. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 879–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, T.S.; Bhattacharjya, S.; Papadimitriou, C.; Bogdanova, Y.; Bentley, J.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C.; Kamalakannan, S.; Refugee Empowerment Task Force, International Networking Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. Lockdown-Related Disparities Experienced by People with Disabilities during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review with Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, E.; Sgandurra, G.; De Nicola, G.; Biagioni, T.; Boldrini, S.; Bonaventura, E.; Buchignani, B.; Della Vecchia, S.; Falcone, F.; Fedi, C.; et al. Behavioural and Emotional Changes during COVID-19 Lockdown in an Italian Paediatric Population with Neurologic and Psychiatric Disorders. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operto, F.F.; Coppola, G.; Vivenzio, V.; Scuoppo, C.; Padovano, C.; de Simone, V.; Rinaldi, R.; Belfiore, G.; Sica, G.; Morcaldi, L.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents with Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Emotional/Behavioral Symptoms and Parental Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Pai, J.; Wolff, C.G.; Aranchipe, C.S.; Kepler, C.K.; Dos Santos, G.A.; Canton, L.A.L.; de Carvalho, A.B.; Richter, S.A.; Nunes, M.L. COVID-19 Pandemic and Autism Spectrum Disorder, Consequences to Children and Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B.A.; Muscatello, R.A.; Klemencic, M.E.; Schwartzman, J.M. The impact of COVID -19 on stress, anxiety, and coping in youth with and without autism and their parents. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 1496–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theis, N.; Campbell, N.; De Leeuw, J.; Owen, M.; Schenke, K.C. The effects of COVID-19 restrictions on physical activity and mental health of children and young adults with physical and/or intellectual disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Shuai, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Lu, L.; Cao, X.; Xia, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R. Acute stress, behavioural symptoms and mood states among school-age children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karci, C.K.; Gurbuz, A.A. Challenges of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2021, 76, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasca, L.; Zanaboni, M.P.; Grumi, S.; Totaro, M.; Ballante, E.; Varesio, C.; De Giorgis, V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic in pediatric patients with epilepsy with neuropsychiatric comorbidities: A telemedicine evaluation. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 115, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, C.; Muggeridge, A.; Cross, J.H. The perceived impact of COVID-19 and associated restrictions on young people with epilepsy in the UK: Young people and caregiver survey. Seizure 2021, 85, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesso, G.; Bonaventura, E.; Buchignani, B.; Della Vecchia, S.; Fedi, C.; Gazzillo, M.; Micomonaco, J.; Salvati, A.; Conti, E.; Cioni, G.; et al. Parental Distress in the Time of COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study on Pediatric Patients with Neuropsychiatric Conditions during Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffagnato, A.; Iannattone, S.; Tascini, B.; Venchiarutti, M.; Broggio, A.; Zanato, S.; Traverso, A.; Mascoli, C.; Manganiello, A.; Miscioscia, M.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study on the Emotional-Behavioral Sequelae for Children and Adolescents with Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Their Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, K.A.; Weiss, J.A.; Howe, S.J.; Kerns, C.M.; McMorris, C.A. Mental Health and Resilient Coping in Caregivers of Autistic Individuals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from the Families Facing COVID Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 52, 3027–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, V.; Albaum, C.; Modica, P.T.; Ahmad, F.; Gorter, J.W.; Khanlou, N.; McMorris, C.; Lai, J.; Harrison, C.; Hedley, T.; et al. The impact of COVID -19 on the mental health and wellbeing of caregivers of autistic children and youth: A scoping review. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2477–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Shang, C.; Liang, H.; Liu, W.; Han, B.; Xia, W.; Zou, M.; Sun, C. Mental health issues in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A multi-time-point study related to COVID-19 pandemic. Autism Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, A.; Pedaci, C.; Palmieri, R.; Simone, M.; Costabile, A.; Craig, F. Psychological impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in children with neurodevelopmental disorders and their families: Evaluation before and during COVID-19 outbreak among an Italian sample. Riv. Psichiatr. 2021, 56, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.; Hastings, R.P.; Totsika, V. COVID-19 impact on psychological outcomes of parents, siblings and children with intellectual disability: Longitudinal before and during lockdown design. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusinato, M.; Iannattone, S.; Spoto, A.; Poli, M.; Moretti, C.; Gatta, M.; Miscioscia, M. Stress, Resilience, and Well-Being in Italian Children and Their Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Fontanesi, L.; Mazza, C.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Roma, P.; Verrocchio, M.C. Parenting-Related Exhaustion During the Italian COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhuzimi, T. Stress and emotional wellbeing of parents due to change in routine for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) at home during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 108, 103822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitsika, V.; Sharpley, C.F.; Andronicos, N.M.; Agnew, L.L. Prevalence, structure and correlates of anxiety-depression in boys with an autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 49-50, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, P.; Rose, J.; Kroese, B.S.; Murphy, G.H.; Langdon, P.E.; Clifford, C.; Hutchings, H.; Watkins, A.; Hiles, S.; Cooper, V. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of carers of people with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohwerder, B.; Wong, S.; Pokharel, S.; Khadka, D.; Poudyal, N.; Prasai, S.; Shrestha, N.; Wickenden, M.; Morrison, J. Describing adolescents with disabilities’ experiences of COVID-19 and other humanitarian emergencies in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Glob. Health Action 2022, 15, 2107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Lau, L.S.T.; Tan, J.X.; Ng, E.D.; Aishworiya, R. Families with Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders During COVID-19: A Scoping Review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, T.; Rescorla, L. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-Informant Assessment; University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, A.; Laghi, F.; Serantoni, G.; Di Blasio, P.; Camisasca, E. Parenting Stress Index—Fourth Edition (PSI-4); Giunti, O.S.: Florence, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Korczak, D.J.; McArthur, B.; Madigan, S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Ren, H.; Cao, R.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, C.; Mei, S. The Effect of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Kakade, M.; Fuller, C.J.; Fan, B.; Fang, Y.; Kong, J.; Guan, Z.; Wu, P. Depression after exposure to stressful events: Lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.-S.; Miao, C.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Jia, F.-Y.; Du, L. COVID-19 and mental health disorders in children and adolescents (Review). Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, E.A.; Ansari, E.; Varrin, P.H.; Sparrow, J. Mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2021, 374, n1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffo, E.; Scandroglio, F.; Asta, L. Debate: COVID-19 and psychological well-being of children and adolescents in Italy. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, T.H.; Friedman, D.; Kaskas, M.M.; Caruso, A.J.; Canenguez, K.M.; Rotter, N.; Wozniak, J.; Basu, A. Brief report of protective factors associated with family and parental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in an outpatient child and adolescent psychiatric clinic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 883955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollberg, D.G.; Hanetz-Gamliel, K.; Levy, S. COVID-19, child’s behavior problems, and mother’s anxiety and mentalization: A mediated moderation model. Curr. Psychol. 2021, Nov 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, S.; Temsah, M.-H.; Alyahya, A.S.; Almadani, A.H.; Almarshedi, A.; Algazlan, M.S.; Alnemary, F.; Bashiri, F.A.; Alkhawashki, S.H.; Altuwariqi, M.H.; et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 on Saudi families and children with special educational needs and disabilities in Saudi Arabia: A national perspective. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 992658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2020, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, S. Parental worry, family-based disaster education and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol.Trauma 2021, 13, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, A.E.; Colvin, M.K.; Beery, C.S.; Koven, M.R.; Vuijk, P.J.; Braaten, E.B. Distinct patterns of emotional and behavioral change in child psychiatry outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Ferrer, M.; Morte-Soriano, M.R.; Begeny, J.; Piedra-Martínez, E. Psychoeducational Challenges in Spanish Children with Dyslexia and Their Parents’ Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Cruz, C.; Espinoza, V.; Donoso, J.; Rosas, R.; Badillo, D. How did the pandemic affect the socio-emotional well-being of Chilean schoolchildren? A longitudinal study. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 37, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanò, E.; Gagliano, A.; Arena, C.; Cedro, C.; Vetri, L.; Operto, F.F.; Pastorino, G.M.G.; Marotta, R.; Roccella, M. Reading-writing di-sorder in children with idiopathic epilepsy. EpilepsyBehave 2020, 111, 107118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, N.; Fors, P.Q.; Eisner, L.; Taigman, J.; Qi, K.; Gorham, L.S.; Camp, C.C.; O’Callaghan, G.; Rodriguez, D.; McGuire, J.; et al. Mood and Behaviors of Adolescents with Depression in a Longitudinal Study Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasa, R.A.; Singh, V.; Holingue, C.; Kalb, L.G.; Jang, Y.; Keefer, A. Psychiatric problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Marín, J.; Gisbert-Gustemps, L.; Setien-Ramos, I.; Español-Martín, G.; Ibañez-Jimenez, P.; Forner-Puntonet, M.; Arteaga-Henríquez, G.; Soriano-Día, A.; Duque-Yemail, J.D.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. COVID-19 pandemic effects in people with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their caregivers: Evaluation of social distancing and lockdown impact on mental health and general status. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2021, 83, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrmann, J.T.; Blaabjerg, J.; Jordansen, J.; Jensen de López, K.M. Systematic Review: Investigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes of Individuals with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 26, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, R.; Karlov, L.; Maugeri, N.; Di Silvestre, S.; Eapen, V. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Wellbeing in the Context of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 3007–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, N.M.; Weems, C.F.; Pellerin, K.; Dalton, R. Parenting Stress and ChildhoodPsycho-pathology: An Examination of Specificity to Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2006, 28, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operto, F.F.; Pastorino, G.M.G.; Scuoppo, C.; Padovano, C.; Vivenzio, V.; Pistola, I.; Belfiore, G.; Rinaldi, R.; de Simone, V.; Coppola, G. Adaptive Behavior, Emotional/Behavioral Problems and Parental Stress in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 751465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Operto, F.; Smirni, D.; Scuoppo, C.; Padovano, C.; Vivenzio, V.; Quatrosi, G.; Carotenuto, M.; Precenzano, F.; Pastorino, G. Neuropsychological Profile, Emotional/Behavioral Problems, and Parental Stress in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operto, F.F.; Mazza, R.; Pastorino, G.M.G.; Campanozzi, S.; Verrotti, A.; Coppola, G. Parental stress in a sample of children with epilepsy. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2019, 140, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Operto, F.F.; Mazza, R.; Pastorino, G.M.G.; Campanozzi, S.; Margari, L.; Coppola, G. Parental stress in pediatric epilepsy after therapy withdrawal. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 94, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).