The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Loneliness, and Social Support in the Psychological Well-Being of a Group of Italian Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youths

Abstract

1. Introduction

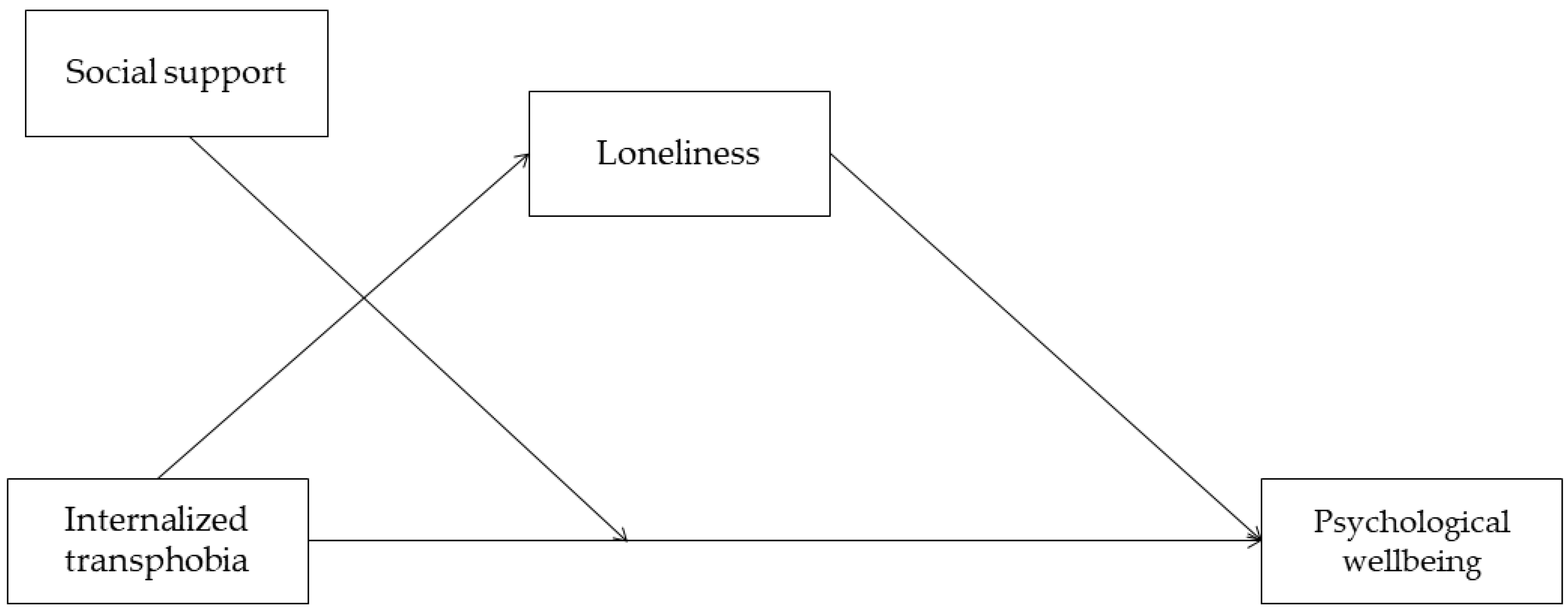

2. The Current Study

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedures

3.3. Measures

3.4. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

4.2. Direct and Indirect Effects of Internalized Transphobia and Loneliness on Psychological Well-Being

4.3. The Moderating Role of Social Support

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 832–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, C.; Bouman, W.P.; Seal, L.; Barker, M.J.; Nieder, T.O.; Tsjoen, G. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tankersley, A.P.; Grafsky, E.L.; Dike, J.; Jones, R.T. Risk and Resilience Factors for Mental Health among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (TGNC) Youth: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, S.C.; Labuski, C.M. The demographics of the transgender population. In International Handbook on the Demography of Sexuality; Baumle, A.K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 289–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, L.C.; Ginieis, M.; Brunet-Icart, I. Strategies for coping with LGBT discrimination at work: A systematic literature review. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 18, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A.; Rothwell, W.R. LGBT workplace inequality in the federal workforce: Intersectional processes, organizational contexts, and turnover considerations. Ilr Rev. 2020, 73, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, E.R.; Blosnich, J.R.; Herman, J.L.; Meyer, I.H. Considerations on sampling in transgender health disparities research. LGBT Health 2019, 6, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Hussain, U. The case for LGBT diversity and inclusion in sport business. Sport Entertain. Rev. 2020, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.P.; Espelage, D.L. Inequities in educational and psychological outcomes between LGBTQ and straight students in middle and high school. Educ. Res. J. LGBT Youth 2011, 40, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M. Introduction: Fear of a Queer Planet. Social Text 1991, 29, 3–17. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/466295 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Thurmond, C.L. The False Idealization of Heteronormativity and the Repression of Queerness. Master’s Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2885 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Nadal, K.L.; Skolnik, A.; Wong, Y. Interpersonal and systemic micro aggressions toward transgender people: Implications for counseling. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2012, 6, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baams, L.; Dubas, J.S.; Russell, S.T.; Buikema, R.L.; van Aken, M.A. Minority stress, perceived burdensomeness, and depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth. J. Adolesc. 2018, 66, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickey, L.M.; Singh, A.A. Social Justice and Advocacy for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Clients. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 38–56. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2137286 (accessed on 11 March 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, M.L.; Testa, R.J. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W.O. Internalized transphobia. In The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality; Whelehan, P., Bolin, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 583–625. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, R.J.; Habarth, J.; Peta, J.; Balsam, K.; Bockting, W.O. Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.A.; Petras, H.; Chen, D.; Chodzen, G. The Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure: Psychometric validity of an adolescent extension. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Bochicchio, V.; Amodeo, A.L.; Esposito, C.; Valerio, P.; Maldonato, N.M.; Bacchini, D.; Vitelli, R. Internalized transphobia, resilience, and mental health: Applying the Psychological Mediation Framework to Italian transgender individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Dolce, P.; Vitelli, R.; Esposito, G.; Testa, R.J.; Balsam, K.F.; Bochicchio, V. Mentalizing stigma: Reflective functioning as a protective factor against depression and anxiety in transgender and gender nonconforming people. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Bockting, W.; Rood, B.A.; Reisner, S.L.; Puckett, J.A.; Surace, F.I.; Berman, A.K.; Pantalone, D.W. Internalized transphobia: Exploring perceptions of social messages in transgender and gender-nonconforming adults. Int. J. Transgend. 2017, 18, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Hughto, J.M.; Gamarel, K.E.; Keuroghlian, A.S.; Mizock, L.; Pachankis, J.E. Discriminatory experiences associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among transgender adults. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, L.C.; Liss, M. Belonging and loneliness as mechanisms in the psychological impact of discrimination among transgender college students. J. LGBT Youth 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Brumer, A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Oldenburg, C.L.; Bockting, W.O. Individual- and structural-level risk factors for suicide attempts among transgender adults. Behav. Med. 2015, 41, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seelman, K.L. Transgender Adults’ Access to College Bathrooms and Housing and the Relationship to Suicidality. J. Homosex. 2016, 63, 1378–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, L.A.; McMorris, B.J.; Eisenberg, M.E. Connections that moderate risk of non-suicidal self-injury among transgender and gender non-conforming youth. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 268, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warr, P. A study of psychological well-being. Br. J. Psychol. 1968, 69, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, A.; Brewster, M.; Velez, B.; Wong, S.; Geiger, E.; Soderstrom, B. Resilience and collective action: Exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A.I. Gender Dysphoria: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2013, 41, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplau, L.A.; Perlman, D. Perspectives on loneliness. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy; Peplau, L.A., Perlman, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, S.; Bashir, A. Relationship between perceived discrimination and loneliness among transgender: Mediating role of coping mechanism. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2014, 3, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schultz, A.J.; Gravlee, C.C.; Williams, D.R.; Israel, B.A.; Mentz, G.; Rowe, Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong Gierveld, J.; van Tilburg, T.; Dykstra, P.A. Loneliness and Social Isolation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships; Vangelisti, A.L., Perlman, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, M.; Victor, C.; Hammond, C.; Eccles, A.; Richins, M.T.; Qualter, P. Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, S.; McKinnon, E.; Hyland, N.B.; Lalanne, C.; Mallal, S.; Nolan, D.; Chassany, O.; Duracinsky, M. HIV-related stigma and physical symptoms have a persistent influence on health-related quality of life in Australians with HIV infection. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodeo, A.L.; Vitelli, R.; Scandurra, C.; Picariello, S.; Valerio, P. Adult attachment and transgender identity in the Italian context: Clinical implications and suggestions for further research. Int. J. Transgend. 2015, 16, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandurra, C.; Vitelli, R.; Maldonato, N.M.; Valerio, P.; Bochicchio, V. A qualitative study on minority stress subjectively experienced by transgender and gender nonconforming people in Italy. Sexologies 2019, 28, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Carbone, A.; Baiocco, R.; Mezzalira, S.; Maldonato, N.M.; Bochicchio, V. Gender identity milestones, minority stress and mental health in three generational cohorts of Italian binary and nonbinary transgender people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Bochicchio, V.; Dolce, P.; Caravà, C.; Vitelli, R.; Testa, R.J.; Balsam, K.F. The Italian validation of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2020, 7, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoen, A.; Goossens, L.; Caes, P. Lonelines in pre-through late adolescence: Exploring the contributions of a multidimensional approach. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melotti, G.; Corsano, P.; Majorano, M.; Scarpuzzi, P. An Italian application of the Louvain Loneliness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LLCA). TPM-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 13, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezza, M.; Principato, C. La rete sociale e il sostegno sociale. In Conoscere la Comunità. L’analisi Degli Ambienti di vita Quotidiana; Prezza, M., Santinello, M., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2002; pp. 193–233. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremigni, P.; Stewart-Brown, S. Una misura del benessere mentale: Validazione italiana della Warwick- Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS). G. Ital. Di Psicol. 2011, 2, 485–505. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 1st ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, A.; Goodman, R. The Impact of Social Connectedness and Internalized Transphobic Stigma on Self-Esteem Among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults. J. Homosex. 2017, 64, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inderbinen, M.; Schaefer, K.; Schneeberger, A.; Gaab, J.; Garcia Nuñez, D. Relationship of Internalized Transnegativity and Protective Factors With Depression, Anxiety, Non-suicidal Self-Injury and Suicidal Tendency in Trans Populations: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 636513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustanski, B.; Liu, R.T. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 42, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.; Knight, S.K.; Hoffman, J.L.; Boscoe-Huffman, S.; Galaska, D.; Arms, M.; Calvert, C. Examining the interplay of religious, spiritual, and homosexual psychological health: A preliminary investigation. In Proceedings of the 115th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–20 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, L.; Matthews, T.L.; Schott, M.R. “That′s so gay!” exploring college students′ attitudes toward the LGBT population. J. Homosex. 2013, 60, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Friedman, R.A.; Kim, H.W. Using social support levels to predict sexual identity development among college students who identify as a sexual minority. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2016, 28, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegarfard, M.; Meinhold-Bergmann, M.E.; Ho, R. Family rejection, social isolation, and loneliness as predictors of negative health outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, and sexual risk behavior) among Thai male-to-female transgender adolescents. J. LGBT Youth 2014, 11, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Scandurra, C.; Freda, M.F.; Pepicelli, G.; Valerio, P.; Vitelli, R. Qualities of mentalization and perception of parental mirroring in a group of Italian transgender people: An empirical study. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2022, 39, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; Singh, A. Supporting Ally Development with Families of Trans and Gender Nonconforming (TGNC) Youth. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2014, 8, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Russell, S.T.; Huebner, D.; Diaz, R.; Sanchez, J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2013, 23, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, M.; Coyne, J. School Psychology in Italy: Current status and challenges for future development. ISPA World Go Round 2017, 45, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci, M.C.; Farrell, P.T. School psychologists in the Italian education system. A mixed-methods study of a district in Northern Italy. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 7, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken, J. Supporting LGBTQ students in high school for the college transition: The role of school counselors. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2017, 20, 1096–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, K.M.; Harper, A.J.; Luke, M.; Singh, A.A. Best practices for professional school counselors working with LGBTQ youth. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2013, 7, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, G. Migrant Sexualities: “Non-normative” Sexual Orientation between Country of Origin and Destination. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 5, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattari, S.K.; Walls, N.E.; Whitfield, D.L.; Langenderfer-Magruder, L. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Experiences of Discrimination in Accessing Social Services Among Transgender/Gender-Nonconforming People. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 2017, 26, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Amodeo, A.L.; Valerio, P.; Bochicchio, V.; Frost, D.M. Minority stress, resilience, and mental health: A study of Italian transgender people. J. Soc. Issues 2017, 73, 564–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Arayasirikul, S.; Raymond, H.F.; McFarland, W. The Impact of Discrimination on the Mental Health of Trans*Female Youth and the Protective Effect of Parental Support. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 2203–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodzen, G.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Chen, D.; Garofalo, R. Minority Stress Factors Associated With Depression and Anxiety Among Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughto, J.M.W.; Reisner, S.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.; Bockting, W.; Botzer, M.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.; DeCuypere, G.; Feldman, J.; Fraser, L.; Green, J.; Knudson, G.; Meyer, W.J.; et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming people, version 7. Int. J. Transgend. 2021, 13, 165–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbre, V.D.; Gaveras, E. The Manifestation of Multilevel Stigma in the Lived Experiences of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.L.; Mann, A.K. Sexual and gender minority health disparities as a social issue: How stigma and intergroup relations can explain and reduce health disparities. J. Soc. Issues 2017, 73, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Gender, Equity and Human Rights. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Case, K.A.; Meier, S.C. Developing allies to transgender and gendernonconforming youth: Training for counselors and educators. J. LGBT Youth 2014, 11, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.; Reisner, S.L.; Honnold, J.A.; Xavier, J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1820–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, S.; Chalungsooth, P.; Teh, Y.K.; Rojanalert, N.; Maneerat, K.; Wong, Y.W.; Macapagal, R.A. Transpeople, transprejudice and pathologization: A seven–country factor analytic study. Int. J. Sex. Health 2009, 21, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) or M ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 23.73 ± 3.59 |

| Range | 18–30 |

| Sex assigned at birth | |

| Male | 22 (27.8) |

| Female | 57 (72.2) |

| Actual gender identity | |

| Binary | 45 (57) |

| Non-binary | 34 (43) |

| Education | |

| ≤high school | 8 (10.1) |

| ≥college | 71 (89.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 76 (96.2) |

| Non-Caucasian | 3 (3.8) |

| Stable relationship | |

| Yes | 38 (48.1) |

| No | 41 (51.9) |

| Community size | |

| Urban | 64 (81) |

| Non-urban | 15 (19) |

| Religious education | |

| Yes | 65 (82.3) |

| No | 14 (17.7) |

| Scales | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internalized transphobia | - | 18.00 (8.66) | 8–40 | |||

| 2. Loneliness | 0.43 *** | - | 2.23 (0.69) | 1–4 | ||

| 3. Social support | −0.32 ** | −0.76 *** | - | 4.85 (1.19) | 1–7 | |

| 4. Psychological well-being | −0.53 *** | −0.62 *** | 0.48 *** | - | 3.08 (0.77) | 1–5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garro, M.; Novara, C.; Di Napoli, G.; Scandurra, C.; Bochicchio, V.; Lavanco, G. The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Loneliness, and Social Support in the Psychological Well-Being of a Group of Italian Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youths. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112282

Garro M, Novara C, Di Napoli G, Scandurra C, Bochicchio V, Lavanco G. The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Loneliness, and Social Support in the Psychological Well-Being of a Group of Italian Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youths. Healthcare. 2022; 10(11):2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112282

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarro, Maria, Cinzia Novara, Gaetano Di Napoli, Cristiano Scandurra, Vincenzo Bochicchio, and Gioacchino Lavanco. 2022. "The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Loneliness, and Social Support in the Psychological Well-Being of a Group of Italian Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youths" Healthcare 10, no. 11: 2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112282

APA StyleGarro, M., Novara, C., Di Napoli, G., Scandurra, C., Bochicchio, V., & Lavanco, G. (2022). The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Loneliness, and Social Support in the Psychological Well-Being of a Group of Italian Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youths. Healthcare, 10(11), 2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112282