High Expressed Emotion and Warmth among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Questionnaires

- A socio-demographic characteristics form collecting relatives’ gender, age, education, marital status, religion, employment status, income, current residence, financial status, family structure, relation to the patient and professional support (psychiatrist, psychologist, group therapy, etc.).

- Camberwell Family Interview (CFI): EE is assessed using the CFI [24], as used in previous Greek studies [25]. The CFI is the gold standard for assessing EE and is a semi-structured interview of the patient’s key relatives. The CFI has five subscales:

- Criticism: the number of critical comments that the relative makes about the patient.

- Hostility: a global scale that shows the relative’s generalized critical attitude and dislike towards the patient as a person and/or shows the relative’s rejection of the patient (0 = absence of hostility, 1 = hostility as a generalization, 2 = hostility as rejection and 3 = both generalization and rejection).

- Emotional overinvolvement: a global rating taken from the whole interview and scored from 0 to 5. This shows how intrusive, self-sacrificing and/or emotionally over-reactive the relative is towards the patient.

- Positive remarks: a frequency count of the number of positive comments that the relative makes in the interview.

- Warmth: a global scale for the warmth the relatives express towards the patient. The aspects considered are the tone of voice, spontaneity, sympathy, concern, empathy and interest in the person. Warmth is scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 5 (0 = no warmth, 1 = very little warmth, 2 = some warmth, 3 = moderate warmth, 4 = moderately high warmth and 5 = high warmth). For the scope of this data analysis, answers were unified in two categories: some or higher warmth = 1 (scores 2, 3, 4, and 5) and no/very little warmth = 0 (scores 0, 1).

- 3.

- Brief COPE: COPE and its different versions are the most widely used scales for assessing coping [26]. The Greek version of the Brief COPE, which has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties, was used [27]. The Brief COPE is a 28-item scale, and the answers to each item are given on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (I have not been doing this at all) to 4 (I have been doing this a lot). The 28 items represent 14 2-item subscales [28,29]. The higher the score on a certain subscale, the higher the use of the specific coping type for the specific stress and problem. The coping styles can be expected to be adaptive or maladaptive and the creator of the questionnaire, Carver C.S., invited researchers to adapt the items of the COPE according to the researcher’s hypotheses, samples and situations [28]. In the current study, eight COPE scales were considered adaptive (namely acceptance, humor, active coping, positive reframing, planning, use of instrumental support, use of emotional support and religion) and six maladaptive (namely behavioral disengagement, self-distraction, self-blame, denial, venting and substance use) [30].

- 4.

- The World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5): this is one of the most popular questionnaires used to assess wellbeing. It has been translated into over 30 languages and has been implemented in five continents. It is a useful tool for assessing subjective wellbeing, taking into account the last fourteen days, and consists of 5 simple questions that are answered on a 6-point Likert-type scale: all of the time = 5, most of the time = 4, more than half of the time = 3, less than half the time = 2, some of the time = 1 and at no time = 0. After scoring the above five questions, there will be a total score of 0–25. This first score is multiplied by the number 4 and a final score of 0–100 is reached. Lower scores represent a worse wellbeing and higher scores represent a better wellbeing [31]. Moreover, the WHO-5 Well-Being Index is used as a screening tool for depression [32].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

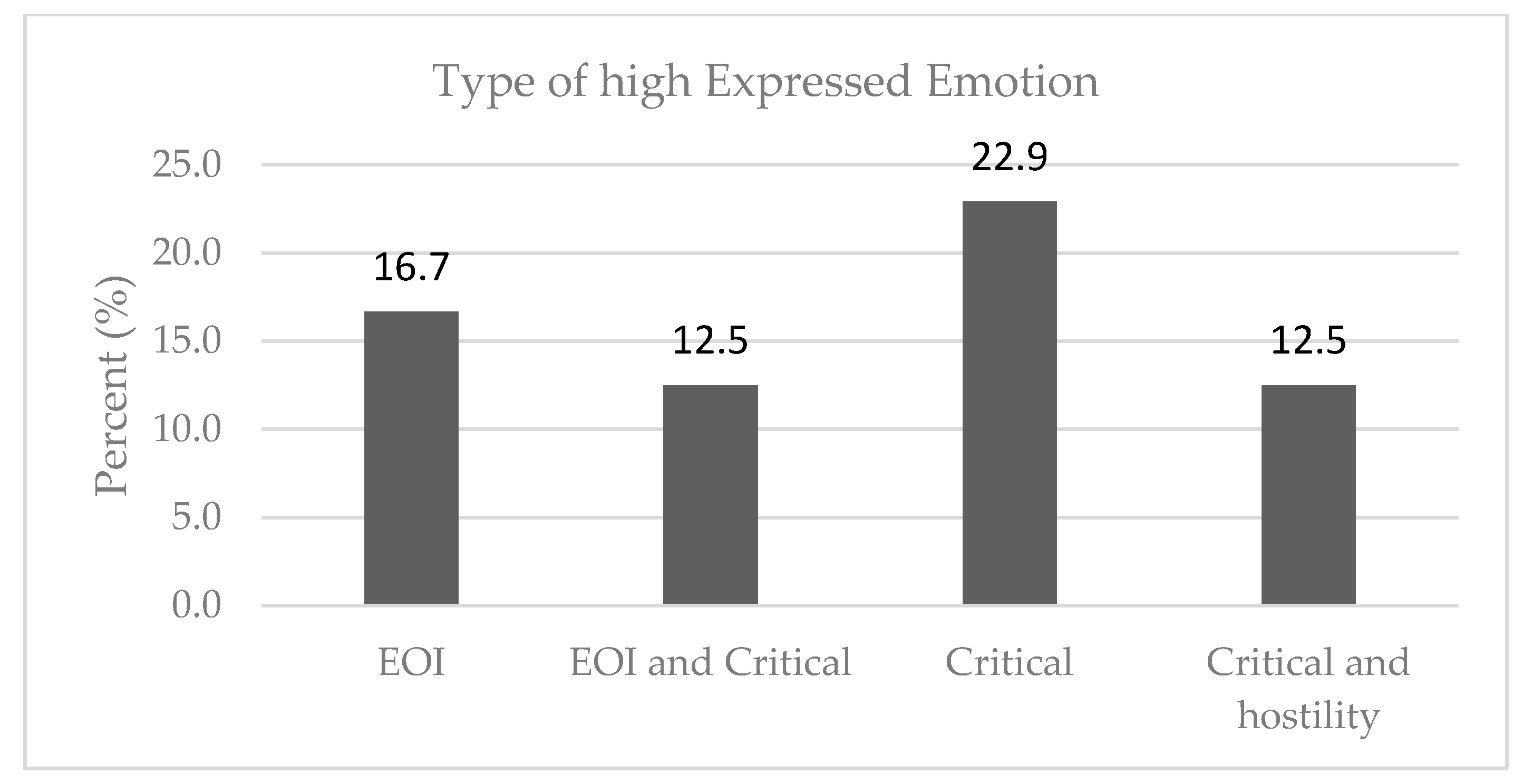

3.2. Expressed Emotion

3.3. Warmth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leff, J.; Vaughn, C. Expressed Emotion in Families; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Butzlaff, R.L.; Hooley, J.M. Expressed Emotion and Psychiatric Relapse: A Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1998, 55, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Pradas, C.; Navarro, J.B.; Pousa, E.; Montero, M.I.; Obiols, J.E. Expressed and Perceived Criticism, Family Warmth, and Symptoms in Schizophrenia. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 16, E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, L.P.; Aakre, J.M.; Docherty, N.M. Schizophrenic Patients’ Perceptions of Stress, Expressed Emotion, and Sensitivity to Criticism. Schizophr. Bull. 2005, 32, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A.; Goldstein, M.J.; Nuechterlein, K.H. Gender Differences in Family Attitudes about Schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 1996, 26, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooley, J.M. Expressed Emotion and Relapse of Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannouli, V.; Tsolaki, M. What Biological Factors, Social Determinants, and Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms of Patients with Mild Alzheimer’s Disease Correlate with Caregiver Estimations of Financial Capacity? Bringing Biases Against Older Women into Focus. ADR 2022, 6, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, M.J.; Hall, D.L.; Carbonella, J.Y.; Weisman de Mamani, A.; Hooley, J.M. Integrity of Literature on Expressed Emotion and Relapse in Patients with Schizophrenia Verified by a p-Curve Analysis. Fam. Proc. 2017, 56, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechnicki, A.; Bielańska, A.; Hanuszkiewicz, I.; Daren, A. The Predictive Validity of Expressed Emotions (EE) in Schizophrenia. A 20-Year Prospective Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.W.; Birley, J.L.T.; Wing, J.K. Influence of Family Life on the Course of Schizophrenic Disorders: A Replication. Br. J. Psychiatry 1972, 121, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claxton, M.; Onwumere, J.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M. Do Family Interventions Improve Outcomes in Early Psychosis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, L.; Yeandle, S. Valuing Carers 2015: The Rising Value of Carers’ Support; Carers: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-873747-52-0. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283726481_Valuing_Carers_2015_-_The_rising_value_of_carers'_support (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Ran, M.-S.; Chui, C.H.K.; Wong, I.Y.-L.; Mao, W.-J.; Lin, F.-R.; Liu, B.; Chan, C.L.-W. Family Caregivers and Outcome of People with Schizophrenia in Rural China: 14-Year Follow-up Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrando, P.; Beltz, J.; Bressi, C.; Clerici, M.; Farma, T.; Invernizzi, G.; Cazzullo, C.L. Expressed Emotion and Schizophrenia in Italy: A Study of an Urban Population. Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 161, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Barrowclough, C.; Lobban, F. Positive Affect in the Family Environment Protects against Relapse in First-Episode Psychosis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, S.R.; Nelson Hipke, K.; Polo, A.J.; Jenkins, J.H.; Karno, M.; Vaughn, C.; Snyder, K.S. Ethnicity, Expressed Emotion, Attributions, and Course of Schizophrenia: Family Warmth Matters. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004, 113, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobban, F.; Postlethwaite, A.; Glentworth, D.; Pinfold, V.; Wainwright, L.; Dunn, G.; Clancy, A.; Haddock, G. A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials of Interventions Reporting Outcomes for Relatives of People with Psychosis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masa’Deh, R. Perceived Stress in Family Caregivers of Individuals with Mental Illness. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2017, 55, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.; Balakrishnan, S.; Ilangovan, S. Psychological Distress, Perceived Burden and Quality of Life in Caregivers of Persons with Schizophrenia. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Pradyumna; Chakrabarti, S. Coping among the Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2015, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A. The Development of Coping: Implications for Psychopathology and Resilience. In Developmental Psychopathology; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–61. ISBN 978-1-119-12555-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shimodera, S.; Mino, Y.; Inoue, S.; Izumoto, Y.; Fujita, H.; Ujihara, H. Expressed Emotion and Family Distress in Relatives of Patients with Schizophrenia in Japan. Compr. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; Berry, K.; Varese, F.; Bucci, S. Are Family Warmth and Positive Remarks Related to Outcomes in Psychosis? A Systematic Review. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1250–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C.; Leff, J. The Measurement of Expressed Emotion in the Families of Psychiatric Patients. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1976, 15, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavreas, V.G.; Tomaras, V.; Karydi, V.; Economou, M.; Stefanis, C.N. Expressed Emotion in Families of Chronic Schizophrenics and Its Association with Clinical Measures. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1992, 27, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. Frequently Used Coping Scales: A Meta-Analysis: Frequently Used Coping Scales. Stress Health 2015, 31, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsou, M.; Panayiotou, G.; Kokkinos, C.M.; Demetriou, A.G. Dimensionality of Coping: An Empirical Contribution to the Construct Validation of the Brief-COPE with a Greek-Speaking Sample. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S. You Want to Measure Coping But Your Protocol’s Too Long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, L.; Spitz, E. Multidimensional assessment of coping: Validation of the Brief COPE among French population. L’encephale 2003, 29, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B. Coping with Severe Mental Illness: Relations of the Brief COPE with Symptoms, Functioning, and Well-Being. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2001, 23, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, T.; Zimmermann, J.; Huffziger, S.; Ubl, B.; Diener, C.; Kuehner, C.; Grosse Holtforth, M. Measuring Depression with a Well-Being Index: Further Evidence for the Validity of the WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) as a Measure of the Severity of Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, D.C.; Ozer, D.J. Evaluating Effect Size in Psychological Research: Sense and Nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 2, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, W.R.; Pratt, K.K.; Hartenstein, J.L.; Jenkins, B.A.; Johnson, G.A. Determining Statistical Signifi Cance (Alpha) and Reporting Statistical Trends: Controversies, Issues, and Facts 1. Compr. Psychol. 2013, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, C.; Sener, S.B.; Angmark, A.; Shaikh, M. Caregiving Processes and Expressed Emotion in Psychosis, a Cross-Cultural, Meta-Analytic Review. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 208, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, D.J. Recent Developments in Expressed Emotion and Schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 160, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutra, K.; Triliva, S.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Stefanakis, Z.; Basta, M.; Lionis, C.; Vgontzas, A.N. Family Functioning in Families of First-Episode Psychosis Patients as Compared to Chronic Mentally Ill Patients and Healthy Controls. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 219, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrà, G.; Montomoli, C.; Clerici, M.; Cazzullo, C.L. Family Interventions for Schizophrenia in Italy: Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 257, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrando, P.; Cecchin, G.; Clerici, M.; Beltz, J.; Milesi, A.; Cazzullo, C.L. Expressed Emotion and Milan Systemic Intervention: A Pilot Study on Families of People with a Diagnosis of Schizophrenia. J. Fam. Ther. 2006, 28, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, I.; Gómez-Beneyto, M.; Ruiz, I.; Puche, E.; Adam, A. The Influence of Family Expressed Emotion on the Course of Schizophrenia in a Sample of Spanish Patients: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 161, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanović, M.; Vuletić, Z.; Bebbington, P. Expressed Emotion in the Families of Patients with Schizophrenia and Its Influence on the Course of Illness. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1994, 29, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, C. Expressed Emotion in Family Therapy: Negative Labelling or an Aid to Recovery? Br. J. Wellbeing 2011, 2, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiono, W.; Kantono, K.; Kristianto, F.C.; Avanti, C.; Herawati, F. Psychoeducation Improved Illness Perception and Expressed Emotion of Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.R.; Nelson, K.A.; Mintz, J. Attributions and Affective Reactions of Family Members and Course of Schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1999, 108, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrowclough, C.; Hooley, J.M. Attributions and Expressed Emotion: A Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 23, 849–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitborde, N.J.K.; López, S.R.; Wickens, T.D.; Jenkins, J.H.; Karno, M. Toward Specifying the Nature of the Relationship between Expressed Emotion and Schizophrenic Relapse: The Utility of Curvilinear Models. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.S.; Knudsen, K.J.; Aschbrenner, K.A. Special Section: A Memorial Tribute: Prosocial Family Processes and the Quality of Life of Persons with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006, 57, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrier, N.; Barrowclough, C.; Andrews, B.; Gregg, L. Risk of Non-Fatal Suicide Ideation and Behaviour in Recent Onset Schizophrenia: The Influence of Clinical, Social, Self-Esteem and Demographic Factors. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.P.; Zinberg, J.L.; Ho, L.; Rudd, A.; Kopelowicz, A.; Daley, M.; Bearden, C.E.; Cannon, T.D. Family Problem Solving Interactions and 6-Month Symptomatic and Functional Outcomes in Youth at Ultra-High Risk for Psychosis and with Recent Onset Psychotic Symptoms: A Longitudinal Study. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 107, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.P.; Zinberg, J.L.; Bearden, C.E.; Lopez, S.R.; Kopelowicz, A.; Daley, M.; Cannon, T.D. Parent Attitudes and Parent Adolescent Interaction in Families of Youth at Risk for Psychosis and with Recent-Onset Psychotic Symptoms: Parent Adolescent Interaction in Family of at-Risk Youth. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2008, 2, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izon, E.; Berry, K.; Law, H.; French, P. Expressed Emotion (EE) in Families of Individuals at-Risk of Developing Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.P.; Gordon, J.L.; Bearden, C.E.; Lopez, S.R.; Kopelowicz, A.; Cannon, T.D. Positive Family Environment Predicts Improvement in Symptoms and Social Functioning among Adolescents at Imminent Risk for Onset of Psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 81, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, M.G.; Taylor, P.J.; Brown, S.L.; Sellwood, W. Attachment, Mentalisation and Expressed Emotion in Carers of People with Long-Term Mental Health Difficulties. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutra, K.; Triliva, S.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Lionis, C.; Vgontzas, A.N. Identifying the Socio-Demographic and Clinical Determinants of Family Functioning in Greek Patients with Psychosis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, T.M. Gender and Emotion Expression: A Developmental Contextual Perspective. Emot. Rev. 2015, 7, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaresha, A.C.; Venkatasubramanian, G. Expressed Emotion in Schizophrenia: An Overview. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2012, 34, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Moone, N.; Harris, P.; Scully, E.; Wellman, N. Understanding the Experiences and Service Needs of Siblings of Individuals with First-Episode Psychosis: A Phenomenological Study: Siblings of People with Psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2012, 6, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, S.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Wade, D.; Howie, L.; McGorry, P. The Impact of First Episode Psychosis on Sibling Quality of Life. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-I.; Hsieh, M.-Y.; Lee, L.-H.; Chen, S.-L. Experiences of Caring for a Sibling with Schizophrenia in a Chinese Context: A Neglected Issue. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 26, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tantawy, A.M.A.; Raya, Y.M.; Zaki, A.-S.M.K. Depressive Disorders Among Caregivers of Schizophrenic Patients in Relation to Burden of Care and Perceived Stigma. Curr. Psychiatry 2010, 17, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Magaña, S.M.; García, J.I.R.; Hernández, M.G.; Cortez, R. Psychological Distress Among Latino Family Caregivers of Adults with Schizophrenia: The Roles of Burden and Stigma. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doval, N.; Sharma, E.; Agarwal, M.; Tripathi, A.; Nischal, A. Experience of Caregiving and Coping in Caregivers of Schizophrenia. Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2018, 12, 113–120B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lambert, C.E.; Lambert, V.A. Predictors of Family Caregivers’ Burden and Quality of Life When Providing Care for a Family Member with Schizophrenia in the People’s Republic of China. Nurs. Health Sci. 2007, 9, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellack, A.S.; Mueser, K.T.; Wade, J.; Sayers, S.; Morrison, R. The Ability of Schizophrenics to Perceive and Cope with Negative Affect. Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 160, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Low EE | High EE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | Effect Size phi | ||

| EE | 17 (35.4) | 31 (64.6) | |||

| Gender | Male | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | 0.135 | 0.22 |

| Female | 9 (28.1) | 23 (71.9) | |||

| Relation | Parent | 10 (25.6) | 29 (74.4) | 0.006 | 0.43 |

| Sibling | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 9 (33.3) | 18 (66.7) | 0.732 | 0.05 |

| Other | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) | |||

| Income | <1000 | 12 (35.3) | 22 (64.7) | 1.000 | 0.01 |

| >1000 | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | |||

| Profession | With their own income | 13 (34.2) | 25 (65.8) | 0.704 | 0.08 |

| Without their own income (students, housekeepers, unemployed) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | |||

| Professional support | No | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0.230 | 0.21 |

| Yes | 16 (40.0) | 24 (60.0) | |||

| Mean ± Std. dev. | Mean ± Std. dev. | p | Effect Size Cohen’s D | ||

| Age (years) | 49.5 ± 17.4 | 51.7 ± 11.8 | 0.940 | 0.16 | |

| Education (years) | 11.7 ± 4.3 | 11.9 ± 3.3 | 0.841 | 0.06 | |

| Number of household members | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 0.035 | 0.65 | |

| Low EE | High EE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scales | Mean ± Std. dev. | Mean ± Std. dev. | P | Effect Size Cohen’s D |

| WHO-5 | 56.0 ± 24.6 | 43.2 ± 19.4 | 0.062 | 0.60 |

| Maladaptive coping | 24.4 ± 6.0 | 25.9 ± 5.1 | 0.346 | 0.28 |

| Adaptive coping | 40.3 ± 6.9 | 41.5 ± 8.5 | 0.503 | 0.14 |

| Demographic Characteristics | No or Very Little Warmth | Some or Higher Warmth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | Effect Size phi | ||

| Warmth | 14 (29.2) | 34 (70.8) | |||

| Gender | Male | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.3) | 0.178 | 0.23 |

| Female | 7 (21.9) | 25 (78.1) | |||

| Relation | Parent | 12 (30.8) | 27 (69.2) | 0.611 | 0.07 |

| Sibling | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 8 (29.6) | 19 (70.4) | 0.936 | 0.01 |

| Other | 6 (28.6) | 15 (71.4) | |||

| Income | <1000 | 9 (26.5) | 25 (73.5) | 0.728 | 0.09 |

| >1000 | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | |||

| Profession | With their own income | 12 (31.6) | 26 (68.4) | 0.704 | 0.08 |

| (students, housekeepers, unemployed) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | |||

| Professional support | No | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0.208 | 0.21 |

| Yes | 10 (25.0) | 30 (75.0) | |||

| Mean ± Std. dev. | Mean ± Std. dev. | P | Effect Size Cohen’s D | ||

| Age (years) | 50.0 ± 13.3 | 51.3 ± 14.3 | 0.768 | 0.09 | |

| Education (years) | 14.1 ± 1.9 | 10.9 ± 3.8 | 0.007 | 0.96 | |

| Number of household members | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 89.0 | 0.729 | 0.09 | |

| No or Very Little Warmth | Some or Higher Warmth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | Effect Size phi | ||

| EE | Low | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) | 0.320 | 0.19 |

| High | 11 (35.5) | 20 (64.5) | |||

| Hostility (2 categories) | No | 9 (23.7) | 29 (76.3) | 0.130 | 0.24 |

| Yes (as generalization, rejection, or both) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | |||

| Mean ± Std. dev. | Mean ±Std. dev. | p | Effect Size Cohen’s D | ||

| CC 1 | 8.4 ± 4.6 | 5.2 ± 4.6 | 0.009 | 0.70 | |

| EOI 2 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 0.002 | 1.18 | |

| Positive Remarks | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 0.179 | 0.57 | |

| No or Very Little Warmth | Some or Higher Warmth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scales | Mean ± Std. dev. | Mean ± Std. dev. | p | Effect Size Cohen’s D |

| WHO-5 | 39.1 ± 20.4 | 51.3 ± 22.0 | 0.073 | 0.56 |

| Maladaptive coping | 28.4 ± 5.0 | 24.1 ± 5.2 | 0.006 | 0.83 |

| Adaptive coping | 42.1 ± 9.7 | 40.6 ± 7.2 | 0.544 | 0.19 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avraam, G.; Samakouri, M.; Tzikos, A.; Arvaniti, A. High Expressed Emotion and Warmth among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Greece. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101957

Avraam G, Samakouri M, Tzikos A, Arvaniti A. High Expressed Emotion and Warmth among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Greece. Healthcare. 2022; 10(10):1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101957

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvraam, Georgios, Maria Samakouri, Anthimos Tzikos, and Aikaterini Arvaniti. 2022. "High Expressed Emotion and Warmth among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Greece" Healthcare 10, no. 10: 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101957

APA StyleAvraam, G., Samakouri, M., Tzikos, A., & Arvaniti, A. (2022). High Expressed Emotion and Warmth among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Greece. Healthcare, 10(10), 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101957