Using Design Thinking Method in Academic Advising: A Case Study in a College of Pharmacy in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Stage 1: Empathise

2.2. Stage 2: Define

2.3. Stage 3: Ideate

2.4. Stage 4: Prototype

2.5. Stage 5: Testing (Validation with Collaborators)

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1 Empathise and Stage 2 Define

- Limited awareness of academic rules and regulations

- Work-family life imbalance

- Lack of trust in academic advising and emotional support

- Unfamiliarity with different learning strategies

- Lack of social life at the university

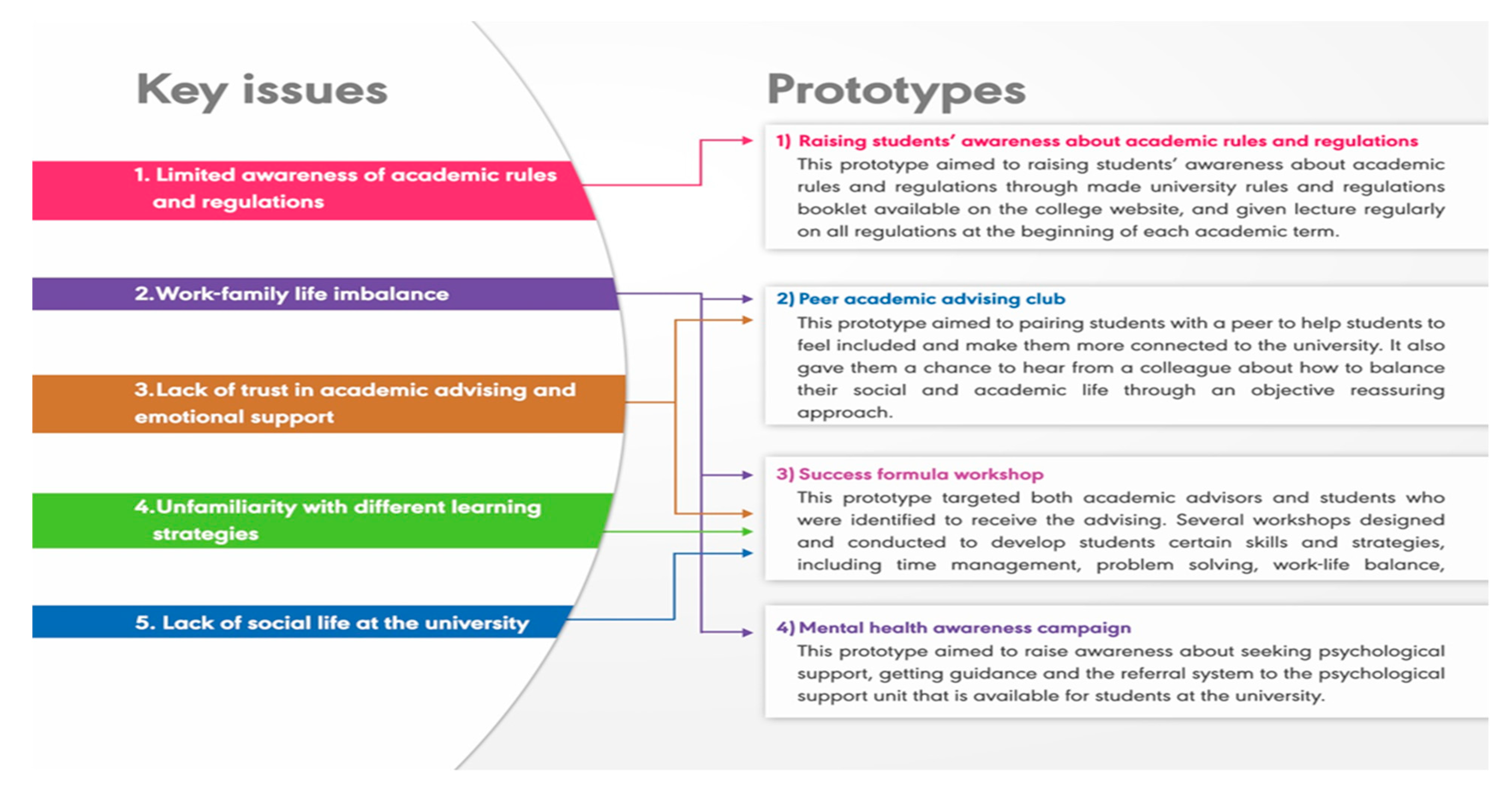

3.2. Stage 3 Ideate and Stage 4 Prototype

3.3. Raising Students’ Awareness about Academic Rules and Regulations

3.4. Peer Academic Advising Club

3.5. Success Formula Workshop

- o

- Problem-solving techniques (fishbone, 5 why, brainstorming, check sheet, Pareto’s Principle of the 80/20 Rule, cost-benefit analysis).

- o

- Work-life balance (work-life triangle, reasons for work-life imbalance, how working hours have changed over time, signs to watch, consequences of losing your work-life balance, work-life balance tips and techniques, time management skills, the Eisenhower matrix, procrastination).

- o

- Real-life examples of students who succeeded in work-life balance (married with kids).

- o

- Real-life examples of students involved in volunteer work.

- o

- Personal values and decision-making.

- o

- Communication skills and volunteer work.

- o

- Learning how to learn (learning in high school versus learning in college, learning taxonomies, strategies for test-taking).

3.6. Mental Health Awareness Campaigns

Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almaghaslah, D.; Alsayari, A.; Alyahya, S.A.; Alshehri, R.; Alqadi, K.; Alasmari, S. Using Design Thinking Principles to Improve Outpatients’ Experiences in Hospital Pharmacies: A Case Study of Two Hospitals in Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2021, 9, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, D. Implementing design thinking in organizations: An exploratory study. J. Organ. Des. 2018, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.P.; Fisher, T.R.; Trowbridge, M.J.; Bent, C. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare 2016, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eines, T.F.; Vatne, S. Nurses and nurse assistants’ experiences with using a design thinking approach to innovation in a nursing home. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dym, C.L.; Agogino, A.M.; Eris, O.; Frey, D.D.; Leifer, L.J. Engineering Design Thinking, Teaching, and Learning. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbell, L. Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I. Des. Cult. 2011, 3, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panke, S. Design Thinking in Education: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges. Open Educ. Stud. 2019, 1, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuhn, T.; Padak, G. From the Co-Editors: Is Academic Advising a Discipline? NACADA J. 2008, 28, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C. Advising by Design: Co-creating Advising Services with Students for Their Success. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Jones, A.D.; Burt, T.D.; Dixon, S.; Hawthorne, M.J. Academic advising: Does it really impact student success? Qual. Assur. Educ. 2013, 21, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Gossett, C.; Simpson, J.; Davis, R. Advising Students for Success in Higher Education: An All-Out Effort. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2019, 21, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, A.E.; Düştegör, D. Prediction of Academic Performance at Undergraduate Graduation: Course Grades or Grade Point Average? Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, Z.; Nazar, H. Exploring the experiences and preparedness of humanitarian pharmacists in responding to an emergency-response situation. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iscan, C.D.; Senemoglu, N. Effectiveness of values education curriculum for fourth grades. Egit. Ve Bilim 2009, 34, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Become a Peer Academic Advisor. Available online: https://paap.due.uci.edu/apply/become-a-paa/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Almanasef, M. Mental Health Literacy and Help-Seeking Behaviours Among Undergraduate Pharmacy Students in Abha, Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ansari, A.; Tantawi, M.E.; AbdelSalam, M.; Al-Harbi, F. Academic advising and student support: Help-seeking behaviors among Saudi dental undergraduate students. Saudi Dent. J. 2015, 27, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peck, A. Peer Involvement Advisors Improve First-Year Student Engagement and Retention. Campus 2011, 16, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, K. Benefits of Peer Advising to Peer Advisers. Mentor Innov. Scholarsh. Acad. Advis. 2008, 10, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Menke, D.J.; Duslak, M.; McGill, C.M. Administrator Perceptions of Academic Advisor Tasks. NACADA J. 2020, 40, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Nichols, C. Do you hear me? Student voice, academic success and retention. Stud. Success 2017, 8, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Close-Ended Question | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| University ID | |

| College | |

| Level | |

| Age | |

| Marital status | |

| Home address | |

| Health status |

|

| Living condition |

|

| Open-Ended Question | |

| Why in your opinion did you obtain this GPA? | |

| Do you have any particular issue that has been affecting your academic achievements? Would you be comfortable to share it with me? | |

| How do you think we can help you (the college, the academic advising unit, academic staff)? | |

| End User Perspectives | Key Problem | Key Management |

|---|---|---|

| Student 3: I did not know much about registration in terms of how many courses [credit hours] I’m supposed to have. Student 11: I wanted to withdraw from a course, but my credit hours would’ve been fewer than 12 and that wasn’t allowed, but I didn’t know that at that time. Student 7: My GPA was less than 2.5 and I got a warning. I wasn’t aware that I’d get one. |

|

|

| Student 5: I live far from campus—about 1.5 h—and having a baby made things even more difficult. Finding a balance between family and studies was challenging. Student 8: I’m expected to help my family with the house chores and sometimes I find it really stressful to manage, especially during mid-terms. Student 19: As a young married woman, I’m struggling to find a balance between university life and family life. Student 20: Being married while studying is hard, but I don’t want to go into details. |

|

|

| Student 4: Sometimes they act like they care, but when I have conflicts in the midterm exam, they don’t seem to care. Student 13: I don’t feel comfortable talking freely with them [academics]. Student 15: I don’t think I can trust them [academics]. |

|

|

| Student 2: I don’t know how to study; I spend so much time in studying. Student 6: All the time I spend studying doesn’t seem to make any difference. This is my last chance; I got my last warning to be expelled from university. |

|

|

| Student 9: I’m between level 5 and level 6. I don’t know anyone in the class. Student 11: I feel isolated, because I’m a repeater and all my batch had already graduated. Student 15: I don’t feel I belong, I’m out of place. I don’t have any friends who would support me. |

|

|

| Statement | Strongly Agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly Disagree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The workshop was applicable to my job | 18 (69.2) | 7 (26.9) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 0 |

| I will recommend this workshop to others | 22 (81.5) | 4 (14.8) | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0 |

| The programme was well placed within the allotted time | 15 (55.6) | 6 (22.2) | 4 (14.8) | 2 (7.4) | 0 |

| The instructor was a good communicator | 22 (81.5) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | 0 |

| The material was presented in an organised manner | 21 (77.8) | 5 (18.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) |

| The instructor was knowledgeable on the topic | 17 (65.4) | 6 (23.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (3.8) |

| I would be interested in attending a follow-up, more advanced workshop on this subject | 22 (88) | 3 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall programme | 18 (72) | 7 (28) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Attendes Opinions about Success Formula Workshop |

|---|

|

| Post-Implementation—Pre-Implementation | N * | Mean Rank | Sum Rank | z | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative ranks | 1 | 1 | 1 | −3.8 | 0.0001 |

| Positive ranks | 18 | 10.5 | 189 | ||

| Equal | 0 | - | - | ||

| Total | 19 | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almaghaslah, D.; Alsayari, A. Using Design Thinking Method in Academic Advising: A Case Study in a College of Pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010083

Almaghaslah D, Alsayari A. Using Design Thinking Method in Academic Advising: A Case Study in a College of Pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2022; 10(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmaghaslah, Dalia, and Abdulrhman Alsayari. 2022. "Using Design Thinking Method in Academic Advising: A Case Study in a College of Pharmacy in Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 10, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010083

APA StyleAlmaghaslah, D., & Alsayari, A. (2022). Using Design Thinking Method in Academic Advising: A Case Study in a College of Pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare, 10(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010083