Abstract

Disruptive behavior creates a dysfunctional culture that has a negative impact on work relations and influences the quality of care and safety of the patient. The objective of the present work is to provide the best methodological quality scientific evidence available on disruptive behavior at a hospital, the aspect associated with the safety of the patient, and its impact on quality of care. For this, we included studies that addressed the prevalence of disruptive behaviors observed in the area of hospital health and its professionals. The selection, eligibility, data extraction and evaluation of the risk of bias stages were conducted by two researchers, and any discrepancies were solved by a third researcher. The data presented show that disruptive behaviors are frequently observed in the daily life of health professionals, and compromise the quality of care, the safety of the patient, and can lead to adverse effects. The results presented indicate that the appearance of disruptive behaviors compromises the quality of care, the safety of the patient, and the appearance of adverse effects, and can also affect the physical and mental health of the health professionals. PROSPERO registration number: CRD42021248798.

1. Introduction

Although no clear consensus exists about the definition of disruptive behavior, authors agree that it creates a dysfunctional culture that has a negative impact on work relations, making difficult interpersonal communication and influencing the quality of care and safety of the patient [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

According to Meneses et al. [8], the main attributes of disruptive behavior are lack of civility and psychological violence, together with consequences such as moral and psychiatric suffering and broken communication. Important information is not shared, resulting in submission and little autonomy. Health centers cannot protect or ignore intimidating or perturbing behaviors, in order to not promote the insecurity of the patients in work contexts that are not healthy for the entire team [9].

In 2008, the Joint Commission International (JCAHO) considered disruptive behavior as threatening, inappropriate behavior, which has a deconstructive effect on the culture of safety, and for this reason, considered it as a Sentinel Event Alert 40, indicating the importance of preventing, managing, and controlling these behaviors among health professionals, including the managing board of the organization. It proposes eleven institutional strategies, highlighting effective and affective leadership and communication. It states that it is the responsibility of the institution to control a hostile environment and provide a proactive culture for safer care, aside from underlining the increase in healthcare costs [10].

Disruptive behaviors are perceived by health professionals as predictors of adverse events (53%), negative impacts with damage to health care (73%), and a contributor to mortality (25%) [11]. In this scenario, we also find medication mistakes linked to the bad relationship between the doctor and nurse. More specifically, it is attributed to the bad communication of verbal orders from the doctor related to the administration of medicines, when doctors become irritated when nurses do not follow their verbal orders until the content of these orders is not clarified [12]. This reminds us of the importance of the indicator “the spoken repetition of the verbal orders (a standardized manner for ensuring understanding)…” as part of the goal “Facilitate an adequate transfer of information and clear communication” proposed by the National Quality Forum of the United States [13] within the framework of “Safe Practices for Better Health Care”, whose objective is to implement and promote indicators of good practices to improve the level of safety of the patient.

Hicks et al. [14] found a variety of disruptive behaviors which entailed the worst clinical practice results, significantly harming the culture of safety. According to Shen et al. [15], one of the main factors which made it difficult to address disruptive behavior in clinical practice was perhaps the “culture of silence”, turning it into a complex process for health workers and institutions, and influencing the safety of the patient.

Therefore, the objective of the present systematic review is to provide the scientific evidence with the best methodological quality, on disruptive behavior at a hospital, the aspects related to the associated safety of the patient, and its impact on the quality of care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This systematic review study was conducted based on the updated version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, 2020) [16,17]. This study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews platform (PROSPERO), on 27 May 2021 (Registration number: CRD42021248798).

2.2. Selection Criteria

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria adopted in the review are related to the research questions: Which are the most frequent disruptive behaviors in the hospital environment and what are their impacts on the safety of the patient? Which are the triggers of these disruptive behaviors perceived by the health professionals?

Therefore, the inclusion criteria were chosen to start with a condition, context, and population (CoCoPop) [18]. Thus, the following studies were selected: those which addressed the prevalence of disruptive behaviors (Co); developed in the area of hospital health (Co); and which evaluated the disruptive behavior of health professionals (Health professionals who provided direct or indirect care, of any gender or race, with at least 3 months of service at any hospital services or unit), and their consequences on the safety of the patient (Pop). We chose to work with studies published between 2014 and 2021, as we observed that studies about the subject were widely investigated in the last 5 years.

As result, studies with non-resident students and studies conducted strictly with the administration of hospital institutions were excluded.

2.3. Sources of Information and Bibliographic Search

Initially, various search strategies were tried in each database. Based on the greater sensitivity and specificity, a standardized search strategy was defined, after which two researchers performed the search independently. The search terms and descriptors (social behavior, disruptive behavior, patient safety, and health professionals, were combined with the Boolean operators AND / OR. The search strategies adopted were applied to the databases selected (PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO and CINAHL).

After the search was conducted in the databases, the article files were collected with the application Rayyan, with which an initial verification was performed to detect the presence of duplicate articles.

During the selection phase, the titles and abstracts of the articles were read to evaluate their compliance with the eligibility criteria. Then, the complete text of the articles selected was read. Additionally, the references from these articles were examined to detect studies that could be potentially relevant. At all the stages, two reviewers were responsible for the reading of the articles, and when a divergence was observed, a third reviewer was consulted.

2.4. Data Extraction

The general information and methodology utilized were collected from each study: title, first author, year of publication, country, the objective of the study, type of disruptive behavior and its frequency, impact on the safety of the patient, and quality of attention, and lastly, type of measuring tools, data analysis, and main results.

2.5. Evaluation of Risk of Bias

The JBI scale (Joanna Bridges Institute) [19] was utilized to evaluate the methodological quality (risk of bias) of the cohort studies (longitudinal) and cross-sectional. The evaluation process was performed by two independent researchers, and any doubt or disagreement was resolved with the help of a third researcher.

2.6. Data Analysis and Synthesis

The general information and the methods applied in the study were extracted. We collected the name of the authors and year of publication, the size of the sample, the measurement instruments utilized in the evaluation of disruptive behaviors, and the main results presented in each study. There was high heterogeneity in the characteristics and size of the samples, in the results, and in the measurement instruments. For these reasons, quantitative synthesis of the data was not possible.

3. Results

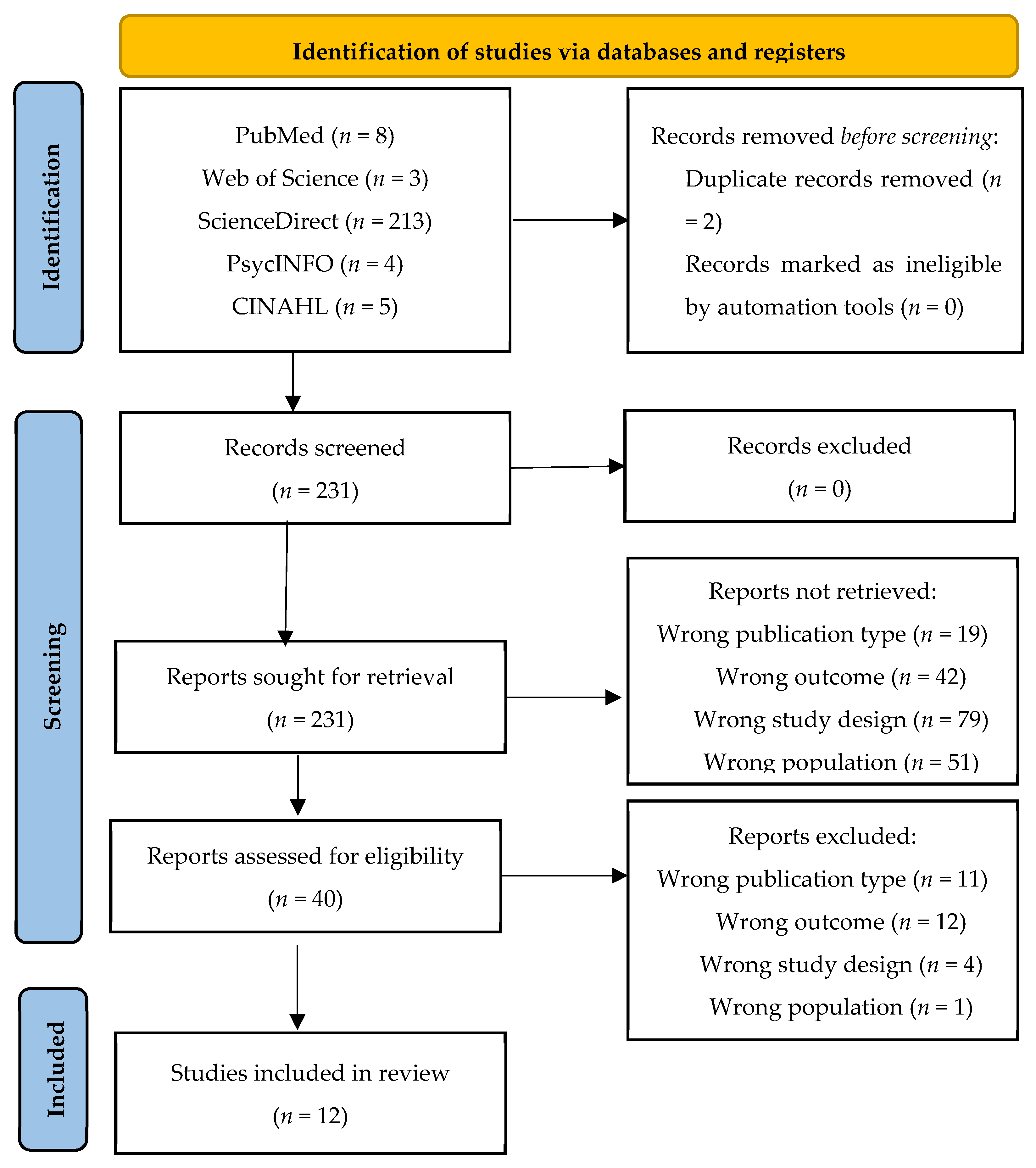

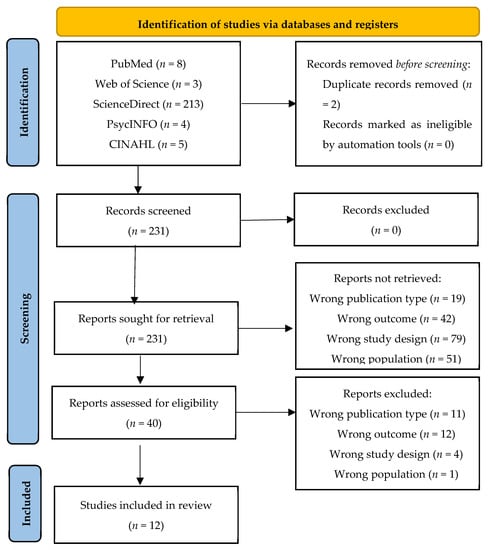

The search in the different databases provided 233 articles, which were screened to evaluate their eligibility. Of these, two were eliminated because they were duplicates. After reading the titles and abstracts, and after reading the complete articles, 12 articles were selected for their systematic review [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This figure shows the flow diagram utilized for the review, based on the PRISMA model (2020).

Of the 12 studies selected, five were conducted in the Unites States [20,23,26,28,29], 2 in Canada [22,30], two in Israel [27,31] and one each in other countries (China, Egypt and Iran) [21,24,25]. The studies included 22,176 health professionals (nurses, doctors, medicine students and technicians).

As for the measurement instruments, high heterogeneity was observed. Different types of scales and questionnaires, validated and adapted to each studied population, were applied. Additionally, these were provided printed or virtually [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Starting with the results described in Table 1, we found that disruptive behavior was frequently observed in the routines of the health professionals [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. With this respect, it was notable that most of the studies on the prevalence of disruptive behaviors in the hospital context could reach or exceed 90% of the occurrence in the last few weeks, months, or years [21,24,25,28,30,31].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review.

The consequences of these disruptive behaviors are documented by health professionals. It was observed that its occurrence can compromise the quality of care, patient safety, and lead to adverse effects [20,21,25,27]. Aside from these negative consequences, it is observed that these disruptive behaviors can lead to physical health (musculoskeletal) and mental (stress, emotional exhaustion, depression, dissatisfaction at work, and sleep disorders) problems of the health professionals in a hospital context [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

In general, the high prevalence of disruptive behaviors and consequences on the quality and safety of the patient, as well as the physical and mental damage of the health professionals re-enforces the need to monitor these behaviors and actions oriented towards collaborative work [31].

With respect to the evaluation of the methodological quality, some weaknesses were found in the evaluation of the exposure, the definition of the criteria to standardize the measurement of the condition, the identification of confounding factors, and the strategies to face these variables (items 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). However, some studies showed an excellent methodological quality [22,26,27].

4. Discussion

The results presented in this systematic review indicate that the appearance of disruptive behaviors can compromise the quality of care, the safety of the patient, and can lead to adverse effects. In the studies included, it was observed that these behaviors can affect the physical and mental health of the health professionals, independently of their profession and length of employment.

At present, the studies on this subject are mainly cross-sectional, through the use of a questionnaire, and are mainly focused on four broad dimensions that are associated with the safety of the patient and the quality of care, considering the possible adverse effects experienced during the process of care derived from the different disruptive behaviors. These dimensions are: Motives and prevalence of disruptive behavior in the health context where the individual factors, the environmental factors, the organizational factors, and the social factors, are relevant, with important correlations observed between abuse and gender, physical abuse and position, and physical abuse and level of education that have generated at least one observed disruptive behavior [30,32,33]; places and moments in which these disruptive behaviors are produced; in this dimension, we highlight the recording of disruptive behavior at emergency services, surgery rooms, and ICU, considered as high complexity due to the variability of the processes and level of care, linked with the physical and emotional workload [20,23]; the types and element characteristics of disruptive behavior: the studies underlined the aspects associated with “intimidation” and “hostility” related with workload and teamwork [26,34]; the strategies and protocols: in most cases, the studies indicated the implementation of a proactive culture by the health professionals in the development of competences in patient safety, team work, and the making of decisions, and by the health institutions, for providing a functional and structural organization for the development of this culture, to promote human qualities at work [8,28,35,36].

With respect to the social-labor variables, a study that analyzed the reports of the notifications observed more disruptive behaviors in the category “physicians” (81%) compared to 52% in the category “nursing”. It was observed that these behaviors result in stress (97%), job dissatisfaction and compromised patient safety (53%), quality of care (72%) and errors (70%) [25].

Another study addressed 2821 nurses, who indicated the existence of a relationship between disruptive behavior and gender. Women indicated that they suffered more verbal and physical abuse than men [28].

Study Limitations

The main limitation of the study is related to the absence of clinical trial studies on disruptive behaviors associated with patient safety. Given the heterogeneity of the studies included in the systematic review, a meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, the findings of this systematic review have led to an update in scientific knowledge in this area, and the results can be further utilized to facilitate decision-making and the implementation of new health policies.

5. Conclusions

The results presented in this systematic review indicate that the appearance of disruptive behaviors compromises the quality of care in the hospital setting. These disruptive behaviors (rudeness, violence in the workplace, feeling of threat, poor distribution of workload and refusal to work in a team) lead to negative consequences, such as the safety of the patient, the appearance of adverse effects, and can also affect the physical and mental health of the health professionals, independently of their profession and the length of employment. Most importantly, it is hoped that these data can be used to develop organizational policies to enhance the workplace and positive patient outcomes within a healthy work environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.-L., C.L.-C. and A.C.D.S.O.; Data curation, P.M.-L. and C.L.-C.; Formal analysis, P.M.-L., C.L.-C. and A.C.D.S.O.; Funding acquisition, P.M.-L.; Investigation, P.M.-L., C.L.-C. and A.C.D.S.O.; Methodology, P.M.-L., C.L.-C., J.L.D.-A., I.J.-R., A.J.R.-M., M.R.-M. and A.C.D.S.O.; Project administration, C.L.-C. and A.C.D.S.O.; Software, P.M.-L., C.L.-C. and A.C.D.S.O.; Supervision, C.L.-C., J.L.D.-A., I.J.-R., A.J.R.-M., M.R.-M. and A.C.D.S.O.; Validation, C.L.-C., J.L.D.-A., I.J.-R., A.J.R.-M., M.R.-M. and A.C.D.S.O.; Visualization, C.L.-C., J.L.D.-A., I.J.-R., A.J.R.-M., M.R.-M. and A.C.D.S.O.; Writing–original draft, P.M.-L., C.L.-C. and A.C.D.S.O.; Writing–review & editing, J.L.D.-A., I.J.-R., A.J.R.-M. and M.R.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| JBI | Joanna Bridges Institute |

| PRISMA-P | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Protocols |

| SR | systematic review |

References

- Rosenstein, A.H. Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. Am. J. Nurs. 2002, 102, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, A.H.; O’Daniel, M. Impact and implications of disruptive behavior in the perioperative arena. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2006, 203, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, A.H.; Naylor, B. Incidence and impact of physician and nurse disruptive behaviors in the emergency department. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 43, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leape, L.L.; Fromson, J.A. Problem doctors: Is there a system-level solution? Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickson, G.; Pichert, J. One step in promoting patient safety: Addressing disruptive behavior. Physician Insurer. Fourth Quart. 2010, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Walrath, J.M.; Dang, D.; Nyberg, D. Hospital RNs’ experiences with disruptive behavior: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2010, 25, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leape, L.L.; Shore, M.F.; Dienstag, J.L.; Mayer, R.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S.P.A.; Meyer, G.S. Perspective: A culture of respect, part 1: The nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meneses, R.; Leitao, I.; Aguiar, L.L.; Oliveira, A.C.S.; Gazos, D.M.; Silva, L.M.S. Evaluating the intervening factors in patient safety: Focusing on hospital nursing staff. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2015, 49, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vessey, J.A.; Demarco, R.; DiFazio, R. Bullying, harassment, and horizontal violence in the nursing workforce: The state of the science. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2010, 28, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Commission. Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentin. Event Alert 2008, 40, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- O’Daniel, M.; Rosenstein, A.H. Professional Communication and Team Collaboration. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses Chapter: Chapter 33; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). Instilling a measure of safety into those whispering down the lane verbal orders. Risk Medicat. Saf. Alert 2001, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum. Safe Practices for Better Health Care: A Consensus Report; Report No.: NQFCR-05-03; NQF: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, S.; Stavropoulou, C. The Effect of Health Care Professional Disruptive Behavior on Patient Care: A Systematic Review. J. Patient Saf. 2020; publish ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.C.; Chiu, H.T.; Lee, P.H.; Hu, Y.C.; Chang, W.Y. Hospital environment, nursephysician relationships and quality of care: Questionnaire survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffman, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 24 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Addison, K.; Luparell, S. Rural Nurses’ Perception of Disruptive Behaviors and Clinical Outcomes: A Pilot Study. Online J. Rural Nurs. Health Care 2014, 14, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoseny, T.A.; Adel, A. Disruptive physician behaviors and their impact on patient care in a health insurance hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2016, 91, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havaei, F.; Astivia, O.L.O.; MacPhee, M. The impact of workplace violence on medical-surgical nurses’ health outcome: A moderated mediation model of work environment conditions and burnout using secondary data. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, R.; Krainovich-Miller, B.; Budin, W.; Djukic, M. Predictors of nurses’ experience of verbal abuse by nurse colleagues. Nurs. Outlook 2018, 66, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Wu, X. A cross-sectional survey on workplace psychological violence among operating room nurses in Mainland China. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2021, 57, e151349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddineshat, M.; Rosenstein, A.H.; Akaberi, A.; Tabatabaeichehr, M. Disruptive Behaviors in an Emergency Department: The Perspective of Physicians and Nurses. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 5, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehder, K.J.; Adair, K.C.; Hadley, A.; McKittrick, K.; Frankel, A.; Leonard, M. Associations between a New Disruptive Behaviors Scale and Teamwork, Patient Safety, Work-Life Balance, Burnout, and Depression. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2020, 46, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskin, A.; Bamberger, P.; Erez, A.; Foulk, T.; Cooper, B.; Peterfreund, I. Incivility and Patient Safety: A Longitudinal Study of Rudeness, Protocol Compliance, and Adverse Events. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2019, 45, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C.R.; Porterfield, S.; Gordon, G.B.S. Disruptive behavior within the workplace. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2015, 28, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecker, M.; Stecker, M. Disruptive staff interactions: A serious source of inter-provider conflict and stress in health care settings. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 35, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafranca, A.; Hiebert, B.; Hamlin, C.; Young, A.; Parveen, D.; Arora, R.C. Prevalence and predictors of exposure to disruptive behaviour in the operating room. Can. J. Anesth. J. Can. D’anesthésie 2019, 66, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warshawski, S. The state of collaborative work with nurses in Israel: A mixed method study. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2016, 31, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, M.; Mokhtari Nouri, J.; Ebadi, A.; Khademolhoseyni, S.M.; Reje, N. The Causes of disruptive behaviors in nursing workforce: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Rev. 2015, 2, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M.G.; Rockne, W.Y.; Braga, R.; Mckellar, S.; Cochran, A. An improved patient safety reporting system increases reports of disruptive behavior in the perioperative setting. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 219, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakhaee, S.; Nasiri, A. Inter-professional Relationships Issues among Iranian Nurses and Physicians: A Qualitative Study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2017, 22, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.; Tschan, F.; Semmer, N.K.; Timm-Holzer, E.; Zimmermann, J.; Candinas, D. Disruptive behavior in the operating room: A prospective observational study of triggers and effects of tense communication episodes in surgical teams. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamblin, L.E.; Essenmacher, L.; Ager, J.; Upfal, M.; Luborsky, M.; Russell, J. Worker-to-worker violence in hospitals: Perpetrator characteristics and common dyads. Workplace Health Saf. 2016, 64, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).