Abstract

A double Roman dominating function on a graph is a function with the properties that if , then vertex u is adjacent to at least one vertex assigned 3 or at least two vertices assigned 2, and if , then vertex u is adjacent to at least one vertex assigned 2 or 3. The weight of f equals . The double Roman domination number of a graph G is the minimum weight of a double Roman dominating function of G. A graph is said to be double Roman if , where is the domination number of G. We obtain the sharp lower bound of the double Roman domination number of generalized Petersen graphs , and we construct solutions providing the upper bounds, which gives exact values of the double Roman domination number for all generalized Petersen graphs . This implies that is a double Roman graph if and only if either (mod 3) or .

1. Introduction

Let be a graph without loops and multiple edges, where and are the vertex set and edge set of G, respectively. If , we say that vertices u and v are adjacent, and v is a neighbor of u. The neighborhood of u, is the set of all neighbors of u, so , and . The set of consecutive integers between a and b with is denoted by and is abbreviated to for short. For convenience, we write when and, similarly, when .

A set D of vertices of G is a dominating set if every vertex in has at least one neighbor in D. The domination number is the cardinality of a minimum dominating set of G. A double Roman dominating function (DRDF) on a graph is a function with the properties that

- , then vertex u is adjacent to at least one vertex assigned 3 or at least two vertices assigned 2 under f;

- if , then vertex u is adjacent to at least one vertex assigned 2 or 3 under f.

In other words, if vertices represent provinces of Roman empire and DRDF represents roman legions, any province either must have a legion that protects it, or, it has to have at least two available legions in the neighborhood that may intervene without leaving the domestic province unprotected. The weight of f equals . The double Roman domination number of a graph G is the minimum weight of a double Roman dominating function of G. A DRDF f is a -function of G if . Given a double Roman dominating function f, we obtain a partition of the vertex set , where . A vertex u is DR-dominated if it is either in or if and it has a neighbor in or if and u has at least one neighbor in or two neighbors in . On the other hand, any partition in which every vertex is DR-dominated obviously gives rise to a double Roman dominating function.

Domination in graphs with its many varieties has been studied extensively in the past [1,2]. Roman domination and double Roman domination is a rather new variety of interest [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Very recently, double Roman domination for cardinal products of graphs was studied in [12], and double Roman trees were characterized in [13]. Cartesian products of certain circles are shown to be double Roman in [14]. It is known that the decision problem associated with is NP-complete for bipartite and chordal graphs, undirected path graphs, chordal bipartite graphs, and circle graphs [15,16,17]. Closely related problems to double Roman domination were studied in [18,19,20].

In this work we will study DRDF on generalized Petersen graphs P(3k, k). More precisely, we will give exact values of the double Roman domination number for all generalized Petersen graphs P(3k, k).

Petersen graphs are among the most interesting examples when considering nontrivial graph invariants. The domination and its variations of generalized Petersen graphs have attracted considerable attention, see for example [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Let n and k be integers where , , and . The generalized Petersen graph is a graph with vertex set and edge set , where , , , , , and subscripts are reduced modulo n. If , we define , , , , for any integer i. Recalling that the subscripts are taken modulo n, it is clear that ; hence, the Petersen graph has exactly k distinct , .

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we mention related previous work, give some more formal definitions, and we formally state our main result. The following sections provide the proof of Theorem 2. In Section 3, the upper bound and the small cases are elaborated. Section 4 is devoted to the proof of the lower bound. Concluding remarks are given in the last section.

2. Preliminaries and Main Result

Beeler et al. [4] initiated the study of the double Roman domination in graphs. They showed that and defined a graph G to be double Roman if , where is the domination number of G. Among other things, Beeler et al. obtained the following result that we recall for a later reference:

Proposition 1

([4]). In a double Roman dominating function f of weight , no vertex needs to be assigned the value 1.

Zhao et al. [29] studied the domination number for the generalized Petersen graphs for integer constants . They obtained upper bound on for general c, and showed that

Theorem 1

([29]). for any .

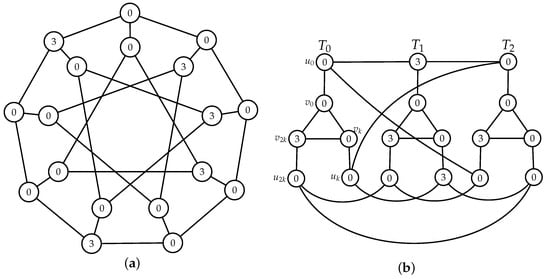

Note that by Proposition 1, we can restrict attention to the DRDF of a graph G with no vertex assigned the value 1. Furthermore, it is easy to see that DRDF of a given graph is not unique. For example, has DRDF’s with value 3 on two vertices and DRDF’s with value 2 on three vertices. Here we will, without loss of generality, consider -functions with minimal . In Figure 1, a DRDF of is given that has minimal number of vertices in , in fact . On the left (a), the usual drawing is given, while on the right (b), we introduce another way of drawing that will be used in the sequel. The vertices are organized according to the triangles, . Vertices of triangle and its neighbors, , are indicated in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

A double Roman dominating function (DRDF) of . Standard drawing (a) and alternative drawing used in this work (b).

In this paper, we provide the double Roman domination numbers of all Petersen graphs and characterize the double Roman graphs among them.

Below we prove Propositions 2 and 3 which imply our main result

Theorem 2.

and its corollary (using Theorem 1):

Corollary 1.

The generalized Petersen graph is a double Roman graph if and only if either (mod 3) or .

In the next section we recall the exact values of for (Lemma 1) and give a sharp upper bound for the general case (Proposition 2). In Section 4 we provide a sharp lower bound (Proposition 3). Lemma 1, Proposition 2, and Proposition 3 together clearly imply Theorem 2.

3. The Upper Bound

In this section, we construct double Roman dominating functions establishing upper bounds for the double Roman dominating numbers. In fact, by Theorem 2 it turns out that these DRDFs are optimal.

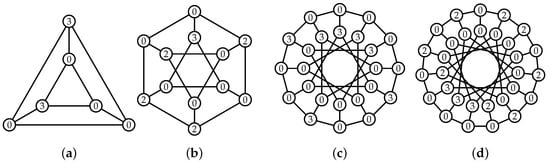

First, let us consider for . It is straightforward to check that the DRDF in Figure 1 and Figure 2 are optimal. We omit the details. For later reference, we state the observation as

Figure 2.

(a) A DRDF of ; (b) A DRDF of ; (c) A DRDF of ; (d) A DRDF of .

Lemma 1.

, , , , and .

In general, the upper bounds are given by

Proposition 2.

For any integer it holds .

Proof.

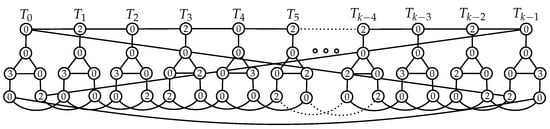

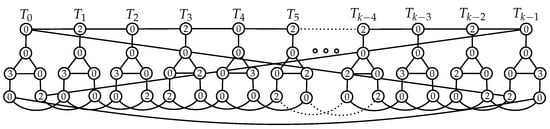

By Lemma 1, the statement holds for . For we provide different constructions depending on . We use a pattern with 6 rows and k columns to represent a DRDF as follows.

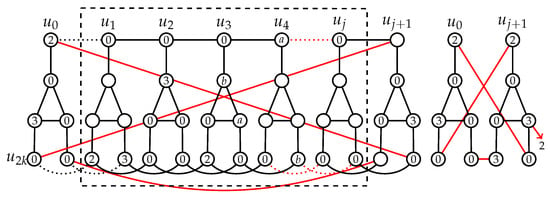

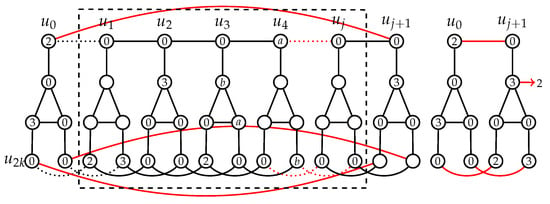

All the constructions below have a part with a repeated pattern and a fixed part at the end. The symbol “−” means that we repeat the leftmost six (or, in one case three) columns of the corresponding pattern times. Hence, we have ℓ repetitions of the pattern plus the rightmost part.

For with , let

It is straightforward to see that f is a DRDF of (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A DRDF of with

For with , let

Then f is a DRDF of .

For with , let

Then f is a DRDF of .

For with , let

Then f is a DRDF of .

For with , let

Then f is a DRDF of . □

4. The Lower Bound

Proposition 3.

For any integer it holds .

We start by some definitions that are used in the proof of the lower bound and in formulation of the results. Recall that we can restrict our attention to the -functions with no vertex assigned the value 1, and in addition, consider only -functions with minimal .

For a DRDF f, let and . Clearly, and as . In other words, for the Petersen graph we have and subscripts of vertices and are taken modulo , but there are exactly k distinct , and therefore subscripts of , and are taken modulo k. Note also that we have and .

As proof that the lower bound is long, we divide the section in several subsections. First, we provide algorithms that for construct a from . In the second subsection, some more definitions and facts are given. Third, fourth, and fifth subsections provide analyses of three special cases. Finally, the proof of Proposition 3 is given.

4.1. Constructions of from for

In this subsection, we describe Algorithms 1–3 that construct from for .

| Algorithm 1: (Algorithm A). |

Input: the graph , , integers and . Output: the graph . Step 1: remove the set of vertices , , along with their incident edges, and denote the resulting graph by Q; Step 2: define the edge set , , and define the graph to have the vertex set and the edge set . return |

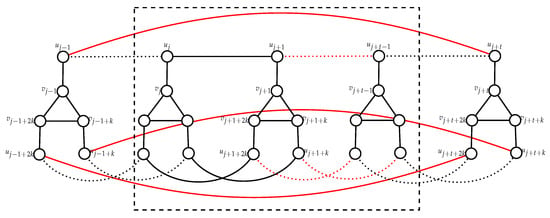

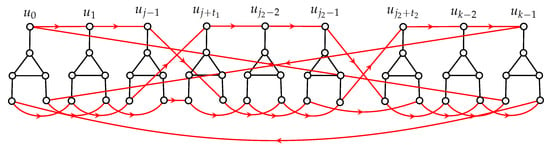

The following lemma is immediate (see Figure 4), and the proof is omitted.

Figure 4.

Illustrating Algorithm A for constructing from .

Lemma 2.

The graph returned by Algorithm A is isomorphic to .

| Algorithm 2: (Algorithm B). |

Input: the graph , , integers and . Output: the graph . Step 1: if , remove the set of vertices , , along with their incident edges, and denote the resulting graph by Q; if , remove the set of edges between and and let Q be a graf and , , ; Step 2: define the edge set , , and define the graph to have the vertex set and the edge set . return |

Lemma 3.

The graph returned by Algorithm B is isomorphic to .

Proof.

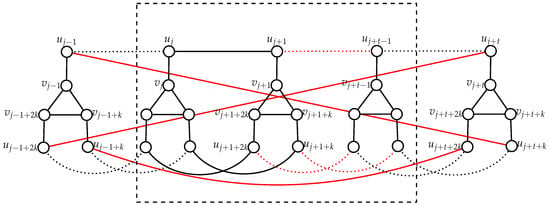

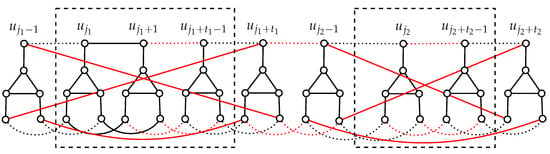

Consider the cycle (see Figure 5). Now we relabel the vertices of as and consider a function with and for each . It can be verified that h is an isomorphism from to and the proof is complete. □

Figure 5.

Illustrating Algorithm B for constructing from .

| Algorithm 3:(Algorithm C). |

Input: the graph , , integers and , where: for , , for , , and for , and . Output: the graph . Step 1: let : for , remove the set of vertices , , along with their incident edges, for , remove the set of edges between and , and denote the resulting graph by Q; Step 2: define the edge set , , , , and define the graph to have the vertex set and the edge set . return |

Lemma 4.

The graph returned by Algorithm C is isomorphic to .

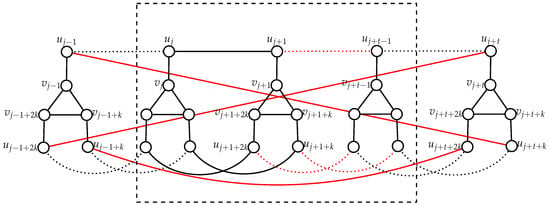

Proof.

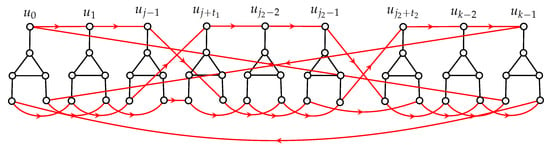

Result of Algorithm C is illustrated on Figure 6. Consider a cycle (see Figure 7 with red arrow lines). Now we relabel the vertices of as and consider a function with and for each . It can be verified that h is an isomorphism from to , and the proof is complete. □

Figure 6.

Illustrating Algorithm C for constructing from .

Figure 7.

A cycle containning all vertices of U in .

4.2. Useful Lemmas and Definitions

Lemma 5.

Let and let f be -function of . Then for each , and if is minimal then for each .

Proof.

Since vertices of can only be DR-dominated by vertices of , we have . Assume that for some . Then let , and for . Clearly, is a DRDF with ; hence, f is not -function, a contradiction. It follows that for each .

Let suppose now that is minimal and for some . Then we must have , and by symmetry, we may assume and for every . To DR-dominate , we must have for some . Then we can construct a function with , and for each . Thus, we have and , contradicting with the assumption that is minimum. □

Lemma 6.

Let and let f be a -function of , such that is minimal. If for some , then .

Proof.

First we will show that there exists -function f such that at least one vertex of is DR-dominated by vertices in for each . Clearly, if for some , or if for some , the statement is true. By Lemma 5, we have ; therefore, it remains to consider the case and . We can construct a function with , and for each . Then, is a DRDF with , as desired. Note that .

Let and let f be -function of , such that is minimal. Assume that and for some . Clearly, then we have , and, without loss of generality, we may assume . It is easy to see that if or then f is not minimal because we can define another function with , (or , respectively), and elsewhere. It remains to consider the case where and , i.e., and . Note that in the case and an arbitrary vertex of the set can be assigned 2 under f.

Let x be the vertex of that is DR-dominated by vertices in . Without loss of generality, we may assume , and . Clearly, if vertex is DR-dominated by vertices in , then f is not minimal because we can define another function with , and elsewhere. It follows that , and , where either or . Now we consider DRDF with , , and for . Thus, we have and , contradicting with the assumption that is minimum. □

From now on we will assume that all DRDFs have minimal . Furthermore, on the basis of the just-proven Lemmas, it is easy to see that we can restrict attention to -functions f of with no neighboring vertices in that are assigned values 2 or more. Formally, for each there are no vertices with , such that both and . It follows, that in each at most one of vertices is assigned by f. Clearly, the case is possible only in with . On the other hand, if then we can assume that and . Thus, in with exactly one of vertices is assigned and two of them are assigned 0. More precisely, for each we have exactly nine possible DRDFs listed below (in the first row are values of vertices of , in the second row are values of vertices of , and each column represents adjacent vertices):

Lemma 7.

Let and let f be a DRDF of . Then for any it holds:

(a) if , then ;

(b) if and , then ;

(c) if and , then ;

(d) if and , then ;

(e) if and , then ;

(f) if and , then ;

(g) if and , then ;

(h) if and , then ;

(i) if and , then ;

(j) if , then .

Proof.

Let f be a DRDF of , , and .

Cases (a,b,c,j). If , then vertices of are DR-dominated by vertices in . In the case (a), exactly one vertex of is dominated by vertices in , and two of them are dominated by two corresponding vertices of which are assigned 3 under f. It follows and thus . In the case (b), two vertices of are dominated by vertices in , and one of them is dominated by the corresponding vertex of , which is assigned 3 under f. Thus, , and the result follows. Similarly, in the case (c), one vertex of is dominated by the corresponding vertex of , which is assigned and the result follows. In the case (j), all vertices of are DR-dominated by vertices in , for which we have three possibilities, i.e., .

Cases (d,e,f,g). If , then one vertex of is DR-dominated by a vertex in , and two of them are dominated by the corresponding vertices of . Consider the values of vertices of , and the result easily follows.

Cases (h,i). In these cases, observe that one vertex of is dominated by a vertex in , which is assigned under f. Hence, as needed. □

Clearly, by symmetry Lemma 7 holds also in the other direction, i.e., for , and , respectively. For example statement (a) can be read as if and , then .

4.3. DRDF with

In Lemmas from 8–11 we will consider DRDF f of with given sequence for some . Without loss of generality, we can set , and in addition we may assume that and . It is easy to see that f is defined as where , and exactly one of the vertices of is assigned 3. Note that we can assume that and because the vertex is DR-dominated by . Furthermore, by Lemma 7 statement (h) we see . In particular, the sequence gives rise to the sequence .

In Lemmas 8–10 we suppose that . Clearly, for and we have ; thus, observations consider the Petersen graphs with .

Let f be a DRDF of . For integer j taken modulo k we denote and .

Lemma 8.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that . If then there exists .

Proof.

Let and let f be a given DRDF of . Suppose to the contrary, that and for each . Then, either or . It follows that either or for each .

For a DRDF f we have . Since and , we may assume . Hence, , a contradiction with . □

Lemma 9.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that . Assume that and let . If for each then and .

Proof.

Let and let f be a given DRDF of with . Let . Then we have and . Without loss of generality, let j be the minimal integer such that , thus we may assume .

(A) First we will prove that . Suppose to the contrary there exists such that and . Then and ; therefore, , thus we have .

We will consider the following two cases.

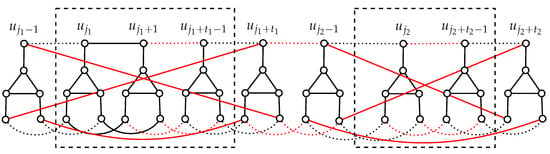

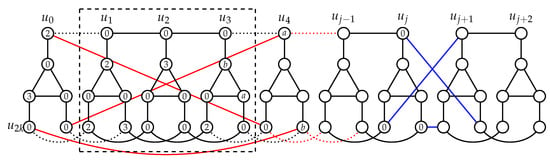

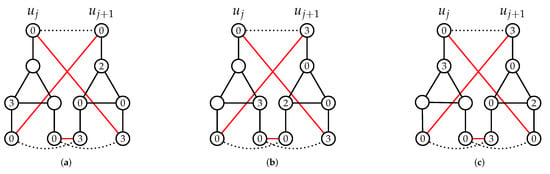

- Case 1: Suppose that .We apply Algorithm C with , , , on a graph . For the resulting graph we have , and by Lemma 4 we have (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Constructing in the proof of Lemma 9, Case 1.Now we let , and furthermore we set ; hence, , , and all vertices of are DR-dominated in a graph . The neighbors of vertices and are pairwise assigned the same values by and f in graph and in graph , respectively. Hence, all vertices of are DR-dominated in a graph . Clearly, if then all vertices of and are DR-dominated in graph . If then there are three different possibilities of assigned values under f of vertices of (see Figure 9). We can see that in all three cases the vertex in has a neighbor in with assigned value in graph . Clearly, these vertices are also adjacent in ; hence, all vertices of are DR-dominated in graph . Furthermore, in all three cases, all vertices of are DR-dominated in graph (see Figure 9). Therefore, is a DRDF of graph .

Figure 8. Constructing in the proof of Lemma 9, Case 1.Now we let , and furthermore we set ; hence, , , and all vertices of are DR-dominated in a graph . The neighbors of vertices and are pairwise assigned the same values by and f in graph and in graph , respectively. Hence, all vertices of are DR-dominated in a graph . Clearly, if then all vertices of and are DR-dominated in graph . If then there are three different possibilities of assigned values under f of vertices of (see Figure 9). We can see that in all three cases the vertex in has a neighbor in with assigned value in graph . Clearly, these vertices are also adjacent in ; hence, all vertices of are DR-dominated in graph . Furthermore, in all three cases, all vertices of are DR-dominated in graph (see Figure 9). Therefore, is a DRDF of graph . Figure 9. The DRDF’s for three subcases of Case 1 in Lemma 9.By assuming that for each , it follows hence , contradicting the assumption .

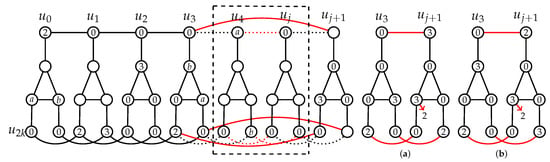

Figure 9. The DRDF’s for three subcases of Case 1 in Lemma 9.By assuming that for each , it follows hence , contradicting the assumption . - Case 2: Assume that .Note that in this case, by Lemma 7 statement (g), we have . From it follows that exactly one of the vertices from is assigned 3 by f. We consider each of these cases below.Case 2.1: Let . Then, and (.We apply Algorithm B with and on a graph , and by Lemma 3, for the resulting graph we have (see Figure 10). Now we let , and in addition we set and ; hence, all vertices of and are DR-dominated in a graph . Even more, we can set , and all vertices remain DR-dominated in a graph . Therefore, is a DRDF of with . Because of the condition , and since and , it follows that . By assumption, we have a contradiction.

Figure 10. Case 2.1 of Lemma 9: .Case 2.2: Let . Then and (.We apply Algorithm A with and on a graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have (see Figure 11). Now we let , and additional we set and ; hence, all vertices of and are DR-dominated in a graph . Similarly as in Case 2.1, we can see that there exists a DRDF of with and , a contradiction.

Figure 10. Case 2.1 of Lemma 9: .Case 2.2: Let . Then and (.We apply Algorithm A with and on a graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have (see Figure 11). Now we let , and additional we set and ; hence, all vertices of and are DR-dominated in a graph . Similarly as in Case 2.1, we can see that there exists a DRDF of with and , a contradiction. Figure 11. Case 2.2 of Lemma 9: .Case 2.3: Let . Then and (.We apply Algorithm A with and on a graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have (see Figure 12). Now we let , additional we set either if , or if (see Figure 12, cases a,b); hence, all vertices of and are DR-dominated in a graph . Similarly as before, in both possibilities, there exists a DRDF of with ; hence, . Recalling the assumption that for each , it follows leading to contradiction.

Figure 11. Case 2.2 of Lemma 9: .Case 2.3: Let . Then and (.We apply Algorithm A with and on a graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have (see Figure 12). Now we let , additional we set either if , or if (see Figure 12, cases a,b); hence, all vertices of and are DR-dominated in a graph . Similarly as before, in both possibilities, there exists a DRDF of with ; hence, . Recalling the assumption that for each , it follows leading to contradiction. Figure 12. Case 2.3 of Lemma 9: .

Figure 12. Case 2.3 of Lemma 9: .

(B) Now assume that there exists such that and .

First assume that . Then , where if .

Because of the condition , it follows that ; therefore, we have . Hence, , which is in contradiction with the assumption . So, we can restrict attention to .

In continuation, the reasoning is analogous to the proof of Case (A). Instead of we consider , and similarly, we apply algorithms on graph ; Algorithm C with , , and in Case 1, Algorithm B and Algorithm A with and in Cases 2.1 and 2.2, respectively; and Algorithm A with and in Case 2.3. □

Lemma 10.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that . Suppose that and let . If for each then and .

Proof.

Let and let f be a given DRDF of with . Let . Then we have and . Without loss of generality, let j be the minimal integer such that ; thus, we may assume .

(A) Assume that . Then ; therefore, , and it follows that . By Lemma 7 statement (f), we have , and thus . Note also that . Namely, if then because of statement (c) of Lemma 7 and if then because of the condition .

We first observe that we have to consider only . The argument is as follows. If , then . Because of the condition , and because of and , it follows that . Thus, , but by assuming , it is a contradiction. Therefore . We will consider the following two cases.

- Case 1: Suppose that . Then (.We apply Algorithm A with and on graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have .Now we let , and in addition we set either ( if ), or (, and if ). Then, in both cases, all vertices of are DR-dominated in a graph . The neighbors of vertices of have pairwise the same assigned values by and f in a graph and in a graph , respectively. hence all vertices of are DR-dominated in graph . Therefore is a DRDF of with , where is equal to 0 if .Because of the condition , and because of and , it follows, that .By assuming, for each , it follows but , a contradiction.

- Case 2. It remains consider the case when . Then . We apply Algorithm A with and on graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have . Now we let , and in addition we set , , and . Similarly as in Case 1, it follows, that is a DRDF of with , and thus, , a contradiction.

(B) Now assume . We will consider the following two cases.

- Case 1. Suppose that . Then (. We apply Algorithm A with and on a graph , and by Lemma 2, for the resulting graph we have .Now we let , and in addition we set . Then, in both cases, all vertices of and are DR-dominated in a graph . Therefore is a DRDF of with . Similarly as before, it follows , but , a contradiction.

- Case 2. It remains consider the case when . Then . We apply Algorithm B with and on a graph , and by Lemma 3, for the resulting graph we have . Now we let , and in addition we set . Similarly as in Case 1, it follows, that is a DRDF of with , a contradiction.

□

Lemma 11.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that for any . If for each then .

Proof.

Let and let f be a DRDF of as given. Observe that if then and .

Let and assume that . By Lemma 8, there exists such that and . By Lemmas 9 and 10 we have . It follows that either or , without loss of generality, say . Then, using Lemma 7 statement (a), we have , a contradiction. Thus . □

4.4. DRDF with

Lemma 12.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that for some . If for each , then .

Proof.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that for some . By Lemma 7, statements (b) and (j), we have and . Furthemore, by Lemma 7, statements (g) and (h), we have and . Therefore, the given sequence gives rise to the sequence .

If then and .

Let and, without loss of generality, we set . Then, , and by symmetry we may assume that , and . It is easy to see that and , otherwise some vertices of are not DR-dominated. In particular, f of vertices of is given by where and exactly one vertex of is assigned 3. Note that we have either ( and ) or , otherwise vertex is not DR-dominated. We will consider the following two cases.

- Case 1. Assume that . Then . We apply Algorithm B with and on graph . For the resulting graph we have , and by Lemma 3, we have . Now we define as follows; we set , , , and for each . It is straightforward to check that in , all vertices are DR-dominated by , hence is a DRDF of . As , it follows that . Hence, assuming that for each , we have , as needed.

- Case 2. Assume now that . Then , otherwise vertex is not DR-dominated, and hence . Furthermore, if then , and if then , otherwise vertices and , respectively, are not DR-dominated. We apply Algorithm A with and on graph . For the resulting graph we have , and by Lemma 2, we have . Now we define as follows; for each . On , we set , , , and for each . On , we set , , , and for each . It is straightforward to check that in , all vertices are DR-dominated by , hence is a DRDF of . As , it follows that . Hence, assuming that for each , we have , as needed.

□

4.5. DRDF with

Lemma 13.

Let and f be a DRDF of such that for some . If for each , then .

Proof.

Let and let f be a DRDF of such that = for some . By Lemma 7, statements (f,j), we have , , and .

Without loss of generality, we set . Then and by symmetry we may assume that , , and . Furthermore, we have ; therefore, exactly one vertex of and exactly one vertex of are assigned 3, and all other vertices of are assigned 0 by f.

Now we will observe values of vertices of . If then and , otherwise vertices and are not DR-dominated. If then either or , and in both cases otherwise vertex is not DR-dominated. More precisely, if then and , and if then and .

Similarly, for vertices of we have the next two possibilities; if , then and and if then and either or .

First we will consider the case where either or . Then it only remains to consider the case where .

- Case 1. Assume that or . Without loss of generality, let . Then and . Furthermore, if then and , if then and , if then and .We apply Algorithm A with and on graph . For the resulting graph we have , and by Lemma 2, we have . Let . It is straightforward to check that in (in all three cases), all vertices are DR-dominated by , therefore is a DRDF of , where . Hence, assuming that for each , we have , as needed.

- Case 2. Assume now that . Then .We apply Algorithm B with and on graph . For the resulting graph we have , and by Lemma 3, we have . Now we define as follows; we set , , and for each . It is straightforward to check that in , all vertices are DR-dominated by , hence is a DRDF of where . Hence, assuming that for each , we have , as needed.

□

4.6. Last Subcase in the Proof of Proposition 3

Lemma 14.

Let and let f be a DRDF of Petersen graph , such that, for each , and . Then .

Proof.

Let and let f be a DRDF of Petersen graph , such that for each , and . We will prove that the average weight is at least 5, i.e., that or, equivalently, that .

Clearly, if for each i, then . By Lemma 7, we know that there are exactly five possible sequences for which , in particular: . By assumption, there is no subsequence . Below we will show that for every with we can define a set of such that their average s is at least 15. More formally, for each i with we define a set of indices such that and the average in is . As it will be easy to see that by construction, the sets are pairwise disjoint, it will follow that the average s is at least 15, more precisely .

- Case 1. Assume .In this case . By Lemma 7, statement (c), we have , hence and . Furthermore, by Lemma 7, statement (a), it follows that .If then and , which implies and we define .If then by Lemma 7, statement (c), , thus , and . Hence and , so we can define (and ).

- Case 2. Assume , thus . By Lemma 7, statement (i), we have , thus . By Lemma 7, statement (f), we have , thus .If , then and we can define .Assume now that . It is easy to see there is only one possible continuation of the sequence: . Then , , and by Lemma 7, statement (f), we have , and we define .

- Case 3. Assume ,thus . By Lemma 7, statement (h), we have , hence . Furthermore, by Lemma 7, statement (d), , thus .If , then let .Assume now that . It is easy to see that there exists only one case: . By Lemma 7, statement (d), we have .If , then . Note that and because of Lemma 7, statement (j), we have , and thus .Let . By symmetry, it is enough to consider . There are three possibilities.

- (a)

- Assume first that . Then we have , and .

- (b)

- Suppose now that . Then, by Lemma 7, statement (c), we have . If , then we obtain the sequence which is not possible by assumption. Therefore , and we have , so we can define .

- (c)

- It remains to consider the case when . We can assume because otherwise we have the sequence , which is not possible. Therefore , thus we have . So we can define .

- Case 4. Finally, let .In this case . By Lemma 7, statement (g), we have and , thus and .If or , then or . Assume now that and . It is easy to see that there is exactly one case with that is left to be considered: . Hence, by Lemma 7, statement (i), we have , implying , so we can define .

To conclude the proof, recall that by definitions we know that for each and we have either or . We omit the details. □

4.7. Section Summary

In all cases, elaborated in previous subsections it was proven that a DRDF must have weight at least under various assumptions that cover all possible cases (recall Lemmas 11–14). Therefore, Proposition 3 follows.

5. Conclusions

We established the double Roman domination numbers of all Petersen graphs . In addition, the double Roman graphs are characterized among them. In our future work, we plan to explore similar statements for some other families such as for .

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to writing and elaborating the proofs. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program under grant 2017YFB0802300, Applied Basic Research (Key Project) of Sichuan Province under grant 2017JY0095, and in part by ARRS, the research agency of Slovenia, grants P1-0222, P2-0248, J1-1693, J1-1692, and J2-2512.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to sincerely thank the three anonymous reviewers for constructive remarks that helped us to improve the presentation substantially.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haynes, H.W.; Hedetniemi, S.; Slater, P. Fundamentals of Domination in Graphs, Marcel Dekker. In Fundamentals of Domination in Graphs; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, H.W.; Hedetniemi, S.; Slater, P. Domination in Graphs: Advanced Topics, Marcel Dekker. In Fundamentals of Domination in Graphs; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ahangar, H.A.; Amjadi, J.; Sheikholeslami, S.M.; Volkmann, L.; Zhao, Y. Signed Roman edge domination numbers in graphs. J. Comb. Optim. 2016, 31, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeler, R.A.; Haynes, T.W.; Hedetniemi, S.T. Double Roman domination. Discret. Appl. Math. 2016, 211, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockayne, E.J.; Dreyer, P.A., Jr.; Hedetniemi, S.M.; Hedetniemi, S.T. Roman domination in graphs. Discret. Math. 2004, 278, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, M.A. A Characterization of Roman trees. Discuss. Math. Graph Theory 2002, 22, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Chang, G.J. Upper bounds on Roman domination numbers of graphs. Discret. Math. 2012, 312, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Chang, G.J. Roman domination on 2-connected graphs. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 2012, 26, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlič, P.; Žerovnik, J. Roman domination number of the Cartesian products of paths and cycles. Electron. J. Comb. 2012, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Wu, P.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Zerovnik, J.; Zhang, X. Discharging Approach for Double Roman Domination in Graphs. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 63345–63351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Kang, L.; Xu, G. The exact domination number of the generalized Petersen graphs. Discret. Math. 2009, 309, 2596–2607. [Google Scholar]

- Klobučar, A.; Klobuxcxar, A. Properties of double Roman domination on cardinal products of graphs. Ars Math. Contemp. 2020, 19, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, H.A.; Amjadi, J.; Atapour, M.; Chellali, M.; Sheikholeslami, S.M. Double Roman trees. Ars Combin. 2019, 145, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhou, X. Some Properties of Double Roman Domination. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, H.A.; Chellali, M.; Sheikholeslami, S.M. On the double Roman domination in graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2017, 232, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Henning, M.A.; Pradhan, D. Algorithmic results on double Roman domination in graphs. J. Comb. Opt. 2020, 39, 90–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, N.J.; Rahbani, H. Some progress on the double Roman domination in graphs. Discret. Math. 2019, 39, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, G.; Volkmann, L.; Mojdeh, D.A. Total double Roman domination in graphs. Commun. Comb. Optim. 2020, 5, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Maimani, H.R.; Momeni, M.; Moghaddam, S.N.; Mahid, F.R.; Sheikholeslami, S.M. Independent Double Roman Domination in Graphs. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2020, 46, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimani, H.R.; Momeni, M.; Mahid, F.R.; Sheikholeslami, S.M. Independent double Roman domination in graphs. AKCE Int. J. Graphs Comb. 2020, 17, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzad, A.; Behzad, M.; Praeger, C.E. On the domination number of the generalized Petersen graphs. Discret. Math. 2008, 308, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ebrahimi, B.J.; Jahanbakht, N.; Mahmoodian, E.S. Vertex domination of generalized Petersen graphs. Discret. Math. 2009, 309, 4355–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, B. On the domination number of generalized Petersen graphs P(n, 2). Discret. Math. 2009, 309, 2445–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, P.; Shao, Z.; Rao, Y.; Liu, J. The Double Roman Domination Numbers of Generalized Petersen graphs P(n, 2). Mathematics 2018, 6, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X. The exact domination number of generalized Petersen graphs P(n,k) with n = 2k and n = 2k + 2. Comput. Appl. Math. 2014, 33, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Lin, X.; Yang, Y.; Luo, M. 2-rainbow domination of generalized Petersen graphs P(n, 2). Discret. Appl. Math. 2009, 157, 1932–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G. 2-rainbow domination in generalized Petersen graphs P(n, 3). Discret. Appl. Math. 2009, 157, 2570–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wei, M.; Li, M.; Liu, G. On the double Roman domination of graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 338, 669–675. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zheng, M.; Wu, L. Domination in the generalized Petersen graph P(ck,k). Util. Math. 2010, 81, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).