Abstract

We discuss a generalization of Berrut’s first and second rational interpolants to the case of equally spaced points on a triangle in .

1. Introduction

Berrut [1,2,3] introduced two versions of a univariate rational interpolation procedure that has proven to be efficient and effective, even for equally spaced points in an interval. Of note is that the complexity of these procedures is linear in the number of points. The derivation of these procedures is based on the classical Whittaker–Shannon sampling theorem [4,5,6]).

Theorem 1.

Suppose that and that for . Then

where, as usual,

is the sinc function.

In the case of f with domain restricted to some compact subinterval of say to considering equally spaced points with we may consider the partial sum

where we have set .

Figure 1 shows a plot of the approximant and of the function where it is evident that when increasing n the quality of the approximation improves.

Figure 1.

for and and .

While (2) no longer reproduces f for all it is an interpolant in that

as easily follows from the cardinality property of the translated sinc functions, i.e.,

This interpolant was already studied by de la Vallée Poussin (1908) who showed that under some weak regularity conditions on

with error essentially of . The reader interested in further details may find them in the excellent survey by Butzer and Stens [7].

In order to alleviate the poor approximation quality of , Berrut in [2] suggested normalizing the Formula (2) for to obtain what we refer to as the first Berrut rational interpolant:

remains an interpolant of f at the nodes but has the advantage of reproducing constants, that is if then .

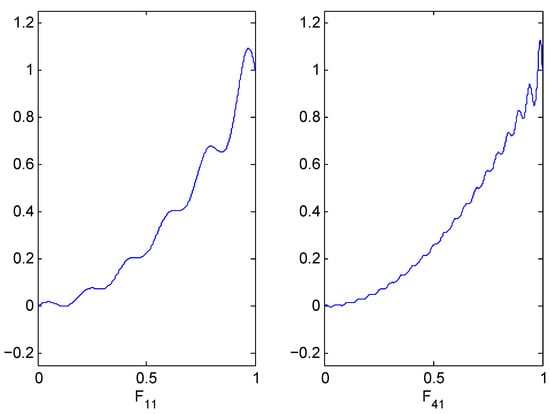

An example of this first interpolant is shown in Figure 2 again for and .

Figure 2.

Berrut for and and .

Remark 1.

Besides being an improved approximant, is also numerically stable as its associated Lebesgue constant has growth, as was shown in [8].

Berrut also proposed a second improvement by making a simple boundary adjustment in the definition of to obtain an interpolant that also reproduced polynomials of degree one. Specifically, let

where

Remark 2.

Floater and Hormann ([9]) subsequently introduced the more general formula

where the weights are chosen so that reproduces polynomials of degree at most d

In the specific case of equally spaced nodes their formula for the reduces to

where , by assumption.

The cases of correspond to Berrut’s first and second interpolants, respectively.

In this work we will consider bivariate extensions of Berrut’s first and second interpolants. The more general Floater-Hormann case will be the topic of a subsequent paper.

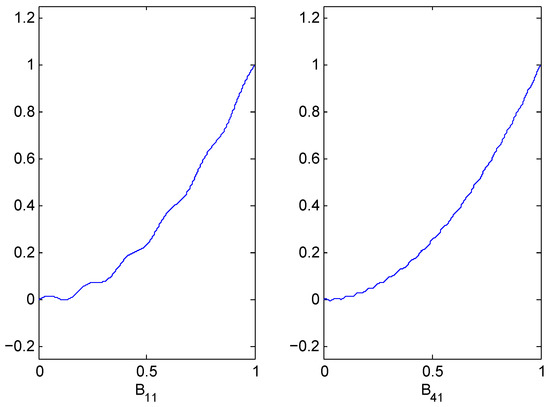

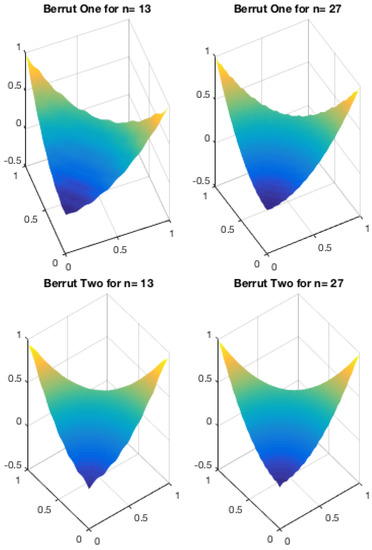

In Figure 3 we show a comparison between the Berrut interpolants for and .

Figure 3.

and for and .

2. The Extension of Berrut’s First Interpolant to Equally Spaced Points on a Triangle

The bivariate Whittaker–Shannon sampling operator is defined as follows. Set and then

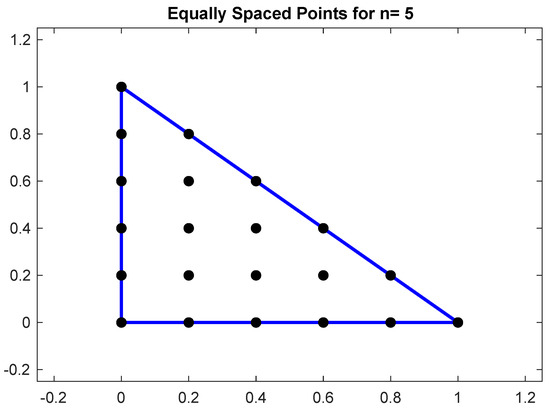

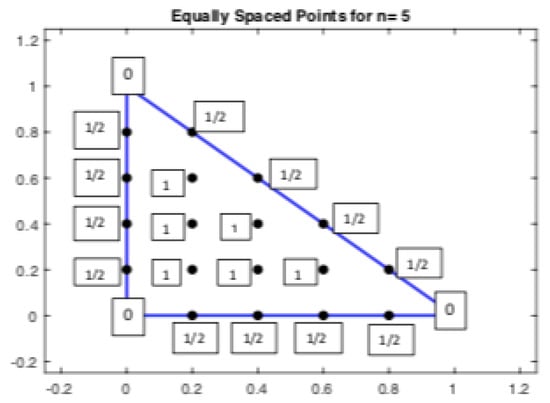

We can now truncate triangularly (this is equivalent to consider equally spaced points on the triangle, as illustrated in Figure 4). Let

be the standard triangle in and set

Figure 4.

Equally Spaced Points in a Triangle.

Furthermore, by normalizing as in the one-dimensional Berrut case, we get

Finally we simplify, just as in the univariate case, to get

Remark 3.

Of course the summation can be truncated to regions P other than just the triangle to obtain multivariate versions of the Berrut rational interpolation at integer lattice points contained in P. However, we consider in this first work only the case of a triangle.

Proposition 1.

We have that is an interpolant, i.e.,

and that reproduces constants. Moreover, restricted to the vertical grid lines and horizontal grid lines agrees with the univariate Berrut interpolant for the interpolation points along those lines.

Proof.

It is easy to verify these properties. Interpolation is guaranteed by the singularities at the interpolation points while the reproduction of constants is self evident.

To see the grid line first rationalize by multiplying the numerator and denominator by where

to obtain

Restricting, for example to the vertical grid line we obtain

However the product

unless . Hence

which is exactly the univariate Berrut interpolant for the function along that the line . □

Remark 4.

The restriction of to the upper edge is not a univariate Berrut interpolant, as is easy to confirm. It follows that is not symmetric with respect to the barycentric coordinates of the triangle.

As we have seen, the formula (11) can be rationalized by multiplying the numerator and denominator by where

Indeed, writing let

be the resulting polynomial for the denominator in (11). The zeros of correspond to poles in the expression for and are obviously problematic. We conjecture however that there are no poles inside the triangle, but have been able to prove this only for to date. We remark that although the univariate arguments used by Berrut (and more generally by Floater and Hormann) do extend easily to the tensor product case, they do not, to the best of our knowledge, extend easily to the triangular case which we are considering.

Our method to do this is elementary, but computationally expensive. Consider first the case. Then

Clearly for but this can also be confirmed by the use of barycentric coordinates. Indeed, let so that . In particular, the triangle T is given by

Then, homogenizing and simplifying we have

As all the coefficients of are non-negative, it follows that on the interior of the triangle T. By, the previous proposition, we know that there are also no boundary poles on the edges and . The upper edge () needs to be checked separately, which is easily done.

For higher degrees n it is convenient to change variables letting so that

where

Then, ignoring the factor and, by an abuse of notation, suppressing the primes,

a polynomial of degree 4. It can be homogenized to

which becomes, upon setting ( in barycentric coordinates),

Not all the coefficients are non-negative and hence we cannot immediately conclude that on T. However, we may degree elevate this expression, i.e., multiply by a factor (cf. e.g., [10]). If it is the case that all the coefficients of the product

are non-negative, it follows that on T. (The lowest power r with this property is related to the so-called Bernstein degree of .) In this case, consider what occurs if . Then

The minimum non-zero coefficient, 1 in this case, provides a certificate of positivity for on the interior of T (where ). Separate certificates for the boundary can be obtained by setting and respectively. However, as already noted, the restrictions of the bivariate interpolant to the edges and are the univariate Berrut interpolants and hence have no poles there. The upper edge needs to be done separately.

By these means we may, with the assistance of a computer algebra system, prove the following positivity result.

Proposition 2.

For at least

Proof.

We produced a positivity certificate for the stated values of n using the Matlab Symbolic Toolbox and the following code.

The minimal values of degree elevation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Degree Elevation r for Degree n.

Notice that the minimal elevation degree r grows quite quickly with n. In principle one can continue with this procedure proving positivity for one degree n at a time. A general proof evades us for the time being. □

In the univariate case it is known that in fact there are no real poles whatsoever. In contrast, in the bivariate case there are real poles, however, due to Proposition 2 they are necessarily outside the triangle.

Proposition 3.

For any set of weights the denominator

has real zeros at for and .

Proof.

Notice that

However, for we must have for all with i.e., either or (or both). Hence at least one of the products

must be zero, and thus . □

Remark 5.

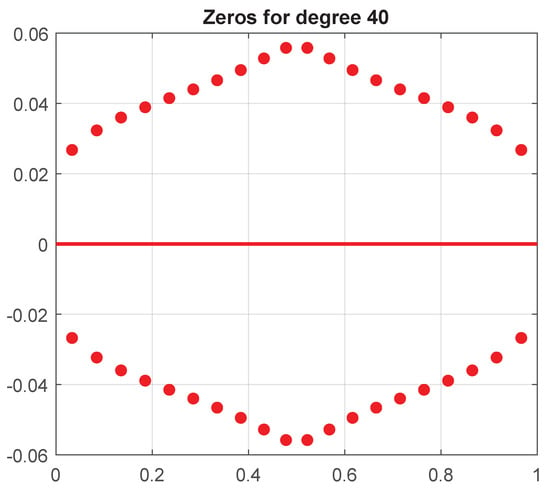

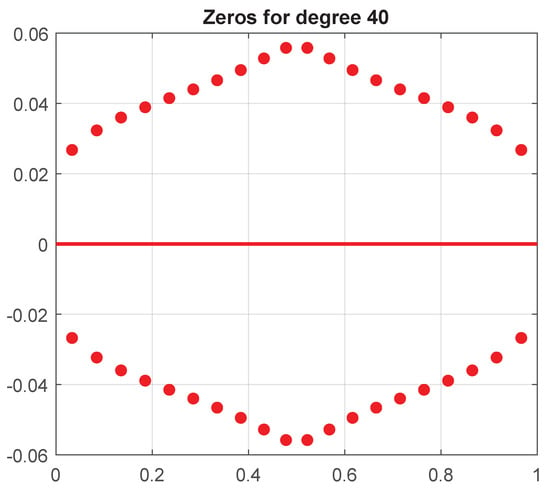

While there are no real poles in the univariate case, there are complex poles. Figure 5 shows these poles for degree . In fact it is possible to analyze the asymptotics of these poles. Indeed, it was shown in [4] that

where is the so-called Bateman G-function

Letting we obtain

However, notice, from the defining formula, that

so that the zeros of are aysmptotically the zeros of divided by n. In particular, one may find numerically that

is a zero of and hence is approximately a zero of . Consequently, in the univariate case, there are complex poles of distance order to the interval whereas in the bivariate case there are real poles of this same order of distance to the triangle T.

Figure 5.

Univariate Poles for Degree .

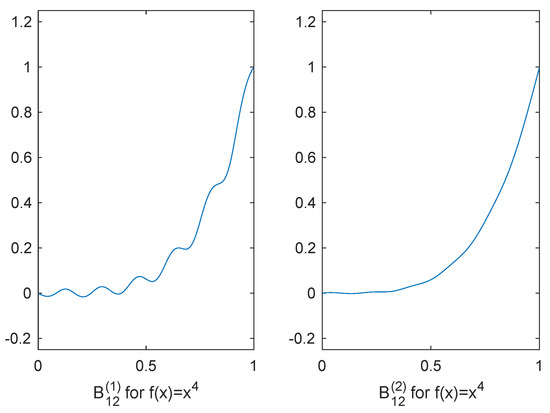

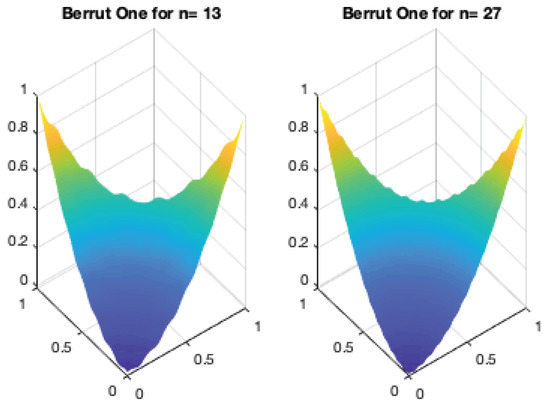

Finally, we show some examples of this bivariate interpolant. Figure 6 shows the bivariate extension of Berrut’s first interpolant for the function and .

Figure 6.

Bivariate Berrut One for .

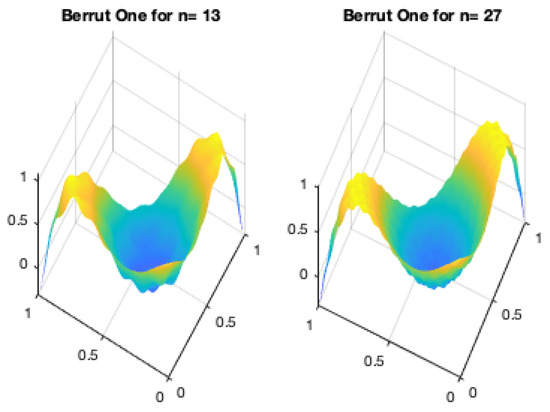

Figure 7 shows the interpolant of for the same degrees.

Figure 7.

Bivariate Berrut One for .

One may notice that the interpolant is reasonable for higher values of n but leaves room for improvement.

A Hybrid Interpolant

For any linear interpolant it is possible, by means of a so-called Boolean sum, to create a hybrid version that reproduces any specifed finite dimensional subspace of functions, the most common example of such being the space of polynomials of degree one. Indeed, for example, if denotes the linear interpolant of f at the three vertices of i.e.,

then for we may defined

where is the interpolant of .

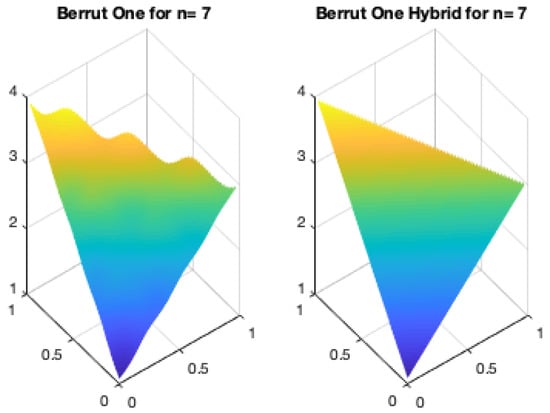

Figure 8 give a comparison between the original and its hybrid version, for and .

Figure 8.

Berrut One and its Hybrid for and .

3. The Extension of Berrut’s Second Interpolant to Equally Spaced Points on a Triangle

Berrut’s second interpolant (for when the boundary points are included) involves the introduction of weights, adjusted at the boundary, to ensure the reproduction of linears. In general, for weights we define

In the bivariate case the reproduction of linears splits into n odd and n even cases. We consider first the n odd case for which we define the weights

(i.e., 0 at the three vertices, at the interior edge points and 1 at the triangle interior points). The case is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Weights on the triangle.

Proposition 4.

For odd and weights given by (13), reproduces polynomials of degree one.

Proof.

We remark that the case has all weights zero, and hence is not relevant. □

We will make use of univariate reproduction formulas for Berrut’s second interpolant.

Lemma 1.

For any points and weights

if and only if

Proof.

We calculate

□

Lemma 2.

Consider the weights

with a parameter. Then for and any or and m odd

Proof.

By Lemma 1 we need only show that .

The case is the result first proved by Berrut and hence we leave out the details. In case and m is odd then we calculate

as this is an alternating sum of with an even () number of terms. □

Now to prove Proposition 4. We wish to show that

for any . Clearly it suffices to show this for which we now proceed to do. First note that, by scaling by a factor of n this is equivalnet to showing that

Now write the summation by rows as

For the first row, the weights correspond to the lower edge and are

and we apply the univariate Lemma with and to obtain

For the other rows, the weights are

and we may apply the univariate Lemma with and to obtain

For the top row (actually a singleton), and so there is nothing to do. □

Remark 6.

The zero weights at the vertices means that will not interpolate at those points. It will however provide an order approximation to the corresponding value of f, provided it is minimally smooth. The approximation properties of these interpolants will be discussed in a forthcoming work.

Just as in the first interpolant case, by Lemma 3, there are poles at . However, just as in the first case, there are no poles in the triangle T.

Proposition 5.

For at least

Proof.

We do this in exactly the same manner as in the first case, by using degree elevation to produce a positivity certificate, one degree at a time. The minimal values of degree elevation are displayed in Table 2. □

Table 2.

Degree Elevation r for Degree n.

The n even case splits into two subcases.

n, A Multiple of Four

In case n is a multiple of four we introduce the weights of 1 at interior points and along each edge

where the bracketed by to the left and right is the middle entry, (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Above: Berrut’s one. Below: Berrut’s two.

We first remark that in the univariate case the rational interpolant with these weights, for n a multiple of four, reproduces linears.

Lemma 3.

For n a multiple of four and the weights given by (14),

Proof.

Applying Lemma 1 we calculate

and the result follows. □

Proposition 6.

For the weights given by (14) and n a multiple of four, the Berrut two extension reproduces linears.

Proof.

We will show that

for any . Again, it suffices to show this for i.e., that

We again proceed row by row. The bottom row is the case discussed in Lemma 3. The other rows, other than for follow from the case of Lemma 2. For we have

Now we claim that

from which the result for the th row follows. To see this just note that for row

The row is completely analogous. □

Just as in the previous cases, by Lemma 3, there are poles at . However, we conjeture that there are no poles in the triangle T.

Proposition 7.

For at least

Proof.

We do this in exactly the same manner as before, by using degree elevation to produce a positivity certificate, one degree at a time. The minimal values of degree elevation are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Degree Elevation r for Degree n.

This concludes the proof. □

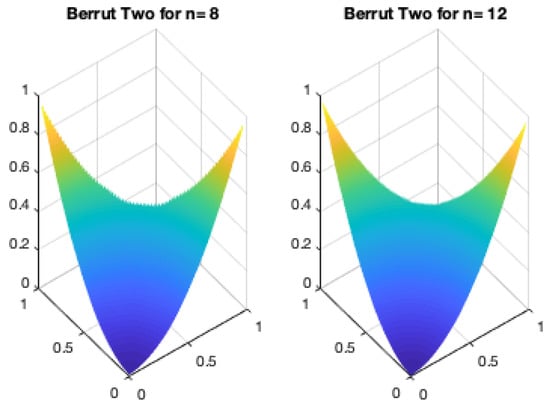

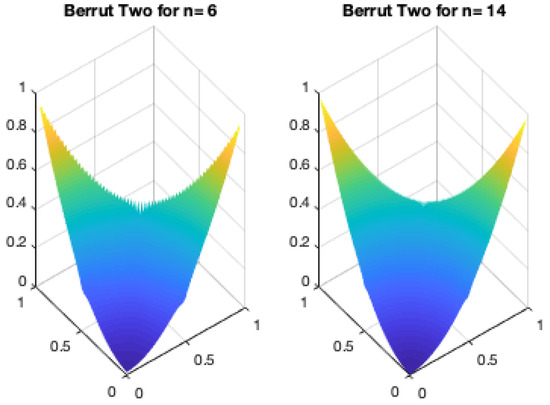

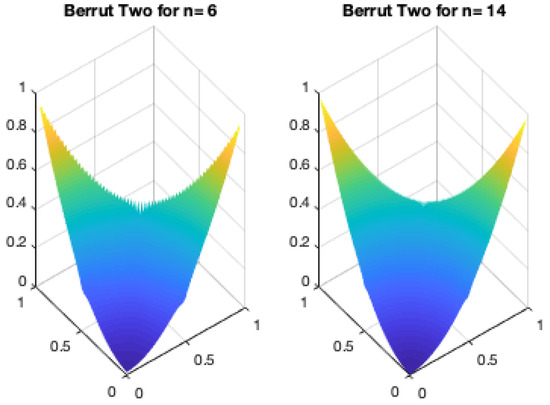

Figure 11 shows the result of interpolating for and .

Figure 11.

Berrut Two for n a multiple of four.

4. n Even, But n/2 Odd

In case n is even but not a multiple of four, i.e., is odd, we introduce the weights of 1 at interior points and along each edge

where the 0 in the middle is the entry, .

We first remark that in the univariate case the rational interpolant with these weights, for n even but odd, reproduces linears.

Lemma 4.

For n even but odd, and the weights given by (15),

Proof.

By Lemma 1, we need only show that

However, in this case

as both are alternating sums of with an even number of terms, for the first sum and for the second. □

Proposition 8.

For n even but odd and the edge weights given by (15), the generalized Berrut interpolant reproduces linears.

Proof.

We again go row by row. The bottom row is the case of Lemma 4. The rows with at the beginning and end are the classical Berrut case, whereas the middle row with weights

is handled by Lemma 2 as, by assumption, is odd (Figure 12). □

Figure 12.

Berrut Two for n even but odd and .

Remark 7.

There are, as always, poles oustide of the triangle T and we conjecture that there are again no poles inside T.

Author Contributions

Writing—review & editing, L.B. and S.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by INdAM-GNCS funds 2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work has been accomplished within the “Rete Italiana di Approssimazione” (RITA), the thematic group on “Approximation Theory and Applications” of the Unione Matematica Italiana (UMI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berrut, J.-P. Baryzentrische Formulen zur trigonometrischen Interpolation I. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 1984, 35, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrut, J.-P. Barycentric Formulae for Cardinal (SINC-) Interpolants. Numer. Math. 1989, 54, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrut, J.-P. Rational functions for guaranteed and experimentally well-conditioned global interpolation. Comput. Math. Appl. 1988, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bos, L.; De Marchi, S. On the Whittaker–Shannon sampling by means of Berrut’s rational interpolant and its extension by Floater and Hormann. East J. Approx. 2011, 17, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whittaker, E.T. On the functions which are represented by the expansions of the interpolation theory. Proc. Roy. Soc. Edinb. 1915, 35, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butzer, P.L.; Stens, R.L. Sampling theory for not necessarily band-limited functions: A historical overview. SIAM Rev. 1992, 34, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, L.; De Marchi, S.; Hormann, K. On the Lebesgue constant of Berrut’s rational interpolation at equidistant nodes. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2011, 236, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Floater, M.S.; Hormann, K. Barycentric rational interpolation with no poles and high rates of approximation. Numer. Math. 2007, 107, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powers, V.; Reznick, B. Polynomials that are positive on an interval. Trans. AMS 2000, 352, 4677–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).