Abstract

Locating arrays (LAs) can be used to detect and identify interaction faults among factors in a component-based system. The optimality and constructions of LAs with a single fault have been investigated extensively under the assumption that all the factors have the same values. However, in real life, different factors in a system have different numbers of possible values. Thus, it is necessary for LAs to satisfy such requirements. We herein establish a general lower bound on the size of mixed-level -locating arrays. Some methods for constructing LAs including direct and recursive constructions are provided. In particular, constructions that produce optimal LAs satisfying the lower bound are described. Additionally, some series of optimal LAs satisfying the lower bound are presented.

1. Introduction

Testing is important in detecting failures triggered by interactions among factors. As reported in [1], owing to the complexity of information systems, interactions among components are complex and numerous. Ideally, one would test all possible interactions (exhaustive testing); however, this is often infeasible owing to the time and cost of tests, even for a moderately small system. Therefore, test suites that provide coverage of the most important interactions should be developed. Testing strategies that use such test suites are usually called combinatorial testing or combinatorial interaction testing (CIT). CIT has shown its effectiveness in detecting faults, particularly in component-based systems or configurable systems [2,3].

The primary combinatorial object used to generate a test suite for CIT is covering arrays (CAs). CAs are applied in the testing of networks, software, and hardware, as well as construction and related applications [4,5,6]. In a CA, the factors have the same number of values; however, in real life, different factors have different numbers of possible values. Thus, mixed-level CAs or mixed covering arrays (MCAs) are a natural extension of covering arrays, which improve their suitability for applications [1,7,8,9,10,11]. A CA or MCA as a test suite can be used to detect the presence of failure-triggered interactions; however, they do not guarantee that faulty interactions can be identified. Consequently, tests to reveal the location of interaction faults are of interest. To address this problem, Colbourn and McClary formalized the problem of non-adaptive location of interaction faults and proposed the notion of locating arrays (LAs) [12].

LAs are a variant of CAs with the ability to determine faulty interactions from the outcomes of the tests. An LA with parameters d and t is denoted by -LA, where d and t represent the numbers of faulty interactions and of components or factors in a faulty interaction, respectively. t is often called strength. When the number of faulty interactions is at most, instead of exactly d, we use the notation -LA to denote it. Generally, testing with a -LA can not only detect the presence of faulty interactions, but can also identify d faulty interactions. Similarly, using a -LA as a test suite allows one to identify all faulty interactions if the number is at most d.

LAs have been utilized in measurement and testing [13,14,15]; however, theoretical studies on LAs are still in an early stage. For example, when the number of factors is arbitrary, only the minimum number of tests in -LA and -LA is known precisely [16]. For other cases, the minimum number of rows in an LA is known only when the number of factors is small [17,18]. When , three recursive constructions are provided in [19]. Apart from these few direct and recursive constructions, computational methods are applied to construct -LAs. Some of these methods use a constraint satisfaction problem (CSP) solver and a satisfiability (SAT) solver [20,21,22]. Lanus et al. [23] described a randomized computational search algorithm called partitioned search with column resampling to construct -LAs. Furthermore, column resampling can be applied to construct -LA with [24]. The second and third authors extended the notion of LAs to expand the applicability to practical testing problems. Specifically, they proposed constrained locating arrays (CLAs) which can be used to detect and locate failure-triggering interactions in the presence of constraints. Computational constructions for this variant of LAs can be found in [25,26,27].

Although a few mathematical constructions exist for -LAs and -LAs, these methods do not treat cases where different factors have difference values. For real-world applications, it is desirable for LAs to satisfy such requirements. Herein, we focus on mixed-level -LAs, which is equivalent to mixed-level -LAs, as we show later.

The contribution of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We provide a lower bound on the size of minimum (i.e., optimal) mixed-level -LAs in a form of a mathematical expression.

- We developed several new mathematical constructions of mixed-level -LAs.

- We prove some conditions that ensure the existence of mixed-level -LAs that achieve the aforementioned lower bound. We also provide mathematical constructions for these optimal mixed-level LAs.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the definitions of basic concepts, such as MCAs and LAs. A general lower bound on the size of mixed-level -LAs is established in Section 3, which will be regarded as benchmarks for the construction of optimal LAs with specific parameters. Some methods for constructing LAs including direct and recursive constructions are provided in Section 4. In particular, some constructions that produce optimal LAs satisfying the lower bound will be described in this section. Section 5 contains some concluding remarks.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Definitions and Notations

The notation represents the set , while the notations and t represent positive integers with . We herein model CIT as follows. Suppose that k factors denoted by exist. The ith factor has a set of possible values (levels) from a set , where . A test is a k-tuple , where for . A test, when executed, has the following outcome: pass or fail. A test suite is a collection of tests, and the outcomes are the corresponding set of pass/fail results. A fault is evidenced by a failure outcome for a test.

Let be an array with entries in the jth column from a set of symbols. A t-way interaction is a possible t-tuple of values for any t-set of columns, denoted by . We denote for the set of rows of A in which the interaction is included. For an arbitrary set of t-way interactions, we define . We use the notation to denote the set of all t-way interactions of A.

The array A is termed MCAs, denoted by MCAλ if for all t-way interactions T of A. In other words, A is an MCA if each sub-array includes all the t-tuples times at the least. Here, the number of rows N is called the array size. The number is termed as the array index. The number of columns k is called the number of factors (or variables), number of components or degree. The word “strength” is generally accepted for referring to the parameter t. When , the notation MCA is used.

When , an MCAλ is merely a CAλ. When in a CA, we omit the subscript. Without loss of generality, we often assume that the symbol set sizes are in a non-decreasing order, i.e., . Hereinafter, these assumptions will continue to be used. When , the presence of the ith factor does not affect the properties of the mixed covering arrays; thus, we often assume that for .

Following [12], if, for any with , we have

then the array A is regarded as a -LA and denoted by -LA. Similarly, the definition is extended to permit sets of at most d interactions by writing in place of d and permitting instead and . In this case, we use the notation -LA. Clearly, the condition is satisfied if In the following, we fully apply this fact.

We herein focus on -LA in this paper. One of the main problems regarding -LA is the construction of such LAs having the minimum N when other parameters have been fixed; however, this is a difficult and challenging problem. The larger the strength t, the more difficult it is to construct a minimum LA. We use the notation -LAN to represent the minimum number N for which a -LA exists. A -LA is called optimal if -LAN.

Lemma 1.

[21] Suppose that A is an array. A is a -LA if and only if it is a -LA and an MCA.

Lemma 1 shows that A is a -LA if A is an MCA and whenever and are distinct t-way interactions. We use this simple fact hereinafter.

2.2. Applications

As stated in Section 1, testing of information systems is the major application of mixed-level LAs. For example, suppose that we want to test a web browser-based software system. Also suppose that using test parameter analysis [2], we have successfully extracted factors and their values to be tested as shown in Table 1. In this example, a test is a tuple of size and there are a total of possible tests.

Table 1.

Factors and values of a web browser-based software system.

Table 2 shows a set of tests that consists of nine of these possible tests. The test set is identical to a -LA, which is represented by the transpose of the following array.

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

Table 2.

Test sets corresponding to locating arrays (LAs).

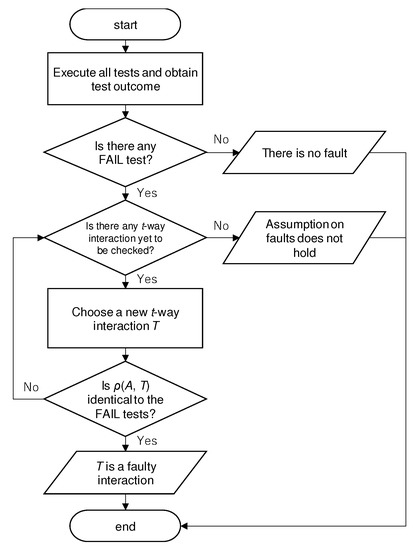

Due to the property that the -LA has, up to one faulty interaction of strength two can always be located using the outcomes of executing these tests. For example, interaction (Chrome, Pro) is faulty if and only if the outcomes of tests 1 and 4 are fail and the others are pass. In mathematical notation, in this case, the interaction is represented as and the set of all present faulty interactions is trivially . The rows (tests) that contain the faulty interaction is , and by definition, never holds for any other such that . The process of locating faulty interactions is schematically presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of locating a fault interaction using a -LA A. is the rows (tests) in which t-way interaction T is included. If no tests failed, then it is concluded that no faults exist. Otherwise, every t-way interaction T is examined: If coincides with the set of FAIL tests, then T is determined to be faulty. If there is no such T, then it is concluded that the assumption on faults does not hold. In this case, for example, there can be multiple faults.

Another application example than information system testing is screening experiments, which aim to identify interactions that are most influential on a response of a complex system. Compared to exhaustive full-factorial designs, using locating arrays as experimental designs greatly decreases the number of design points, thus reducing the cost of experiments. In [13], mixed-level LAs were applied to the screening experiment for TCP throughput of a mobile wireless network.

3. A Lower Bound on the Size of -LA

A benchmark to measure the optimality for -LA is described in this section. It follows from Lemma 1 that A is a -LA only if A is an MCA, which implies that for any t-way interaction T of A. Consequently, -LAN, where . Suppose that A is a -LA with , where . Then, A is an MCA by Lemma 1. Because , we have for any t-way interaction . As , there exists at least one t-way interaction such that . Thus, for a certain . This contradicts the fact that A is a -LA. This observation implies the following lemma.

Lemma 2.

Let . Then, -LAN.

It is remarkable that the lower bound on the size of -LA in Lemma 2 can be achieved. We will present some infinite classes of optimal -LA satisfying the lower bound in the next section. When , where , we can obtain a lower bound on the size of -LA by a similar argument to the proof of Theorem 3.1 in [18]. We state it as follows.

Lemma 3.

Let . If , where , then -LAN.

Proof.

Let A be a -LA. We can obtain an array by selecting the last columns of A (if , then is merely A). In the array , for any , we write , where .

As stated above, for any t-way interaction T of . Consequently, and hold. It is deduced that . It is clear that is a -LA by Lemma 1. Thus, in any two of sets, s with share no common elements. Hence, , which implies that , i.e., . Hence, . □

Based on and in Lemma 3, the following corollary can be easily obtained. It serves as a benchmark for a -LA, which was first presented in [18].

Corollary 1.

Let and k be integers with . Then, -LAN.

In a -LA, we often assume that . Lemma 2 and Lemma 3 consider the cases and , respectively. The left case is , which is considered in the following lemma.

Lemma 4.

Let . If , then -LAN, where

Proof.

From the above argument, it is known that -LAN. Suppose that A is a -LA, where and . Select the last columns of A to form an array . Clearly, is a -LA. Similar to the proof of Lemma 3, we can prove that . When , we can obtain . For , we prove that , i.e., . Without loss of generality, suppose that contains two parts: the first part is an array B containing an sub-array comprising all t-tuples over ; the left part is an array C; (if , then ).

If , then at least one -way interaction exists such that it is not included by any row of C (If , then all the -way interactions satisfy the condition. We can choose an arbitrary one). Hence, we have for any t-way interaction . Since A is a -LA, for any t-way interaction . It is clear that with .

Because , at least one t-way interaction exists such that . Otherwise, for any t-way interaction , which implies that , but . It follows that , where is a certain t-way interaction of . It is obvious that . Consequently, is not a -LA. Thus, . Consequently, if . □

Combining Lemmas 2–4, a lower bound on the size of -LA can be obtained, which serves as a benchmark to measure the optimality.

Theorem 1.

Let . Then, -LAN

- 1.

- , if ;

- 2.

- , if , where ;

- 3.

- , if and ;

- 4.

- , if and .

Table 3 presents a lower bound on the size of certain mixed-level -LAs. The first column lists the types, while the second column displays the lower bound on the size of mixed-level -LAs with the type. The last column presents the size obtained by simulated annealing [28].

Table 3.

Lower bounds on the size of -LA.

A -LA is called optimal if its size is -LAN. In what follows, we focus on some constructions for mixed level LAs from combinatorial design theory. Some constructions that produce optimal LAs satisfying the lower bound in Lemma 2 will also be provided.

4. Constructions of -LA

Some constructions and existence results for -LA are presented in this section.

4.1. Methods for Constructing -LA

In this subsection, we modify some constructions for MCAs to the case of -LAs. The next two lemmas provide the “truncation” and “derivation” constructions, which were first used to construct mixed CAs.

Lemma 5.

(Truncation) Let . Then, -LAN-LAN.

Proof.

Let A be a -LA with -LAN. Delete the ith column from A to obtain a -LA. Thus, -LAN-LAN. □

Lemma 6.

(Derivation) Let . Then -LAN-LAN, where .

Proof.

Let A be a -LA with -LAN. By Lemma 1, A is an MCA and a -LA. For each , taking the rows in A that involve the symbol x in the ith columns and omitting the column yields an MCA. We use to denote the derived array. Next, we prove that is a -LA. In fact, for any -way interactions and with , if , we can form two t-way interactions and by inserting into and , respectively. Hence, , where but . Consequently, A is not a -LA. It is clear that -LAN for . Thus, -LAN. □

The following product construction can be used to produce a new LA from old LAs, which is a typical construction in combinatorial design.

Construction 1.

(Product Construction) If both a -LA and an MCA exist, then a -LA exists, where . In particular, if both a -LA and a -LA exist, then a -LA also exists, where .

Proof.

Let and be the given -LA and MCA, respectively. We form an array as follows. For each row of A and each row of B, include the row as a row of , where .

From the typical method in design theory, the resultant array is an MCA, as both A and B are MCAs. By Lemma 1, we only need to prove that is a -LA. Suppose that , where and with . It is noteworthy that the projection on the first component of and is the corresponding t-way interaction of A, while the projection on the second component is the corresponding t-way interaction of B. Therefore, A is not a -LA. The first assertion is then proved because a -LA is an MCA. The second assertion can be proven by the first assertion. □

The following construction can be used to increase the number of levels for a certain factor.

Construction 2.

If a -LA exists, then a -LA exists, where and .

Proof.

Let be the given -LA with entries in the ith column from a set of size . For a certain , we replace the symbols in the ith column of A by , respectively. We denote the resultant array by . Clearly, permuting the symbols in a certain column does not affect the property of -LAs. Thus, is also a -LA, where entries in the ith column of from the set . Subsequently, write . It is easy to prove that M is a -LA and an MCA. By Lemma 1, M is the desired array. □

The following example illustrates the idea in Construction 2.

Example 1.

The transpose of the following array is a -LA

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Replace the symbols by in the 3th column, respectively. Juxtapose two such arrays from top to bottom to obtain the following array M; we list it as its transpose to conserve space.

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

It is easy to verify that M is a -LA.

Replace the symbol 0 by 2 in the 3th column. Juxtapose two such arrays from top to bottom to obtain the following array ; we list it as its transpose to conserve space.

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

It is easy to verify that is a -LA. □

Remark 1.

Construction 2 may produce an optimal -LA. For example, a -LA is shown in Table 1. By Construction 2, we can obtain a -LA, which is optimal by Lemma 4.

Fusion is an effective construction for MCAs from CAs, for example, see [29]. As with CAs, fusion for -LAs guarantees the extension of uniform constructions to mixed cases; however, fusion for a -LA may not produce mixed-level -LAs. This problem can be circumvented by introducing the notion of detecting arrays (DAs). Suppose that all the factors have the same levels. If, for any with and any , we have then the array A is called a -DA or a -DA.

Construction 3.

(Fusion) Suppose that A is a -DA with . If A is also a -LA, then a -LA exists, where .

Proof.

Let A be a -DA over the symbol set V of size v. Suppose that are positive integers with . It is clear that there exists a certain such that and , where . We select elements from V in the ith column of A to form the element sets , respectively. The elements in are identical with , respectively. Then, we obtain an array . Clearly, is an MCA. We only need to prove that is a -LA by Lemma 1, i.e., for any two distinct t-way interactions and , we have . It is clear that and when and . Hence, .

When and , we can obtain a t-way interaction of A, where . If , then ; however, ; as such, it is a contradiction that A is a -DA. If and , then the similar argument can prove the conclusion.

When and , it is clear that if . The case remains to be considered. Without loss of generality, suppose that elements are identical with . It is clear that and can be obtained from and by fusion, respectively, where and are sets of t-way interactions with . If , then . It is a contradiction that A is a -LA because the existence of -LA implies the existence of -LA [12]. □

Constructions 2 and 3 provide an effective and efficient method to construct a mixed-level -LA from a -LA. The existence of -DA with implies the existence of -LA [12]. Hence, the array A in Construction 3 can be obtained by a -DA, which is characterized in terms of super-simple OAs. The existence of super-simple OAs can be found in [17,30,31,32,33,34]. It is noteworthy that the derived array is not optimal. In the remainder of this section, we present two “Roux-type” recursive constructions [35].

Construction 4.

If both a -LA and a -LA exist, then a -LA exists, where .

Proof.

Let A and B be the given -LA and -LA, respectively. Clearly, if , then A is the required array. Now, suppose that . Insert a column vector of length to the front of the ith column of B to form an array , where . Let . Clearly, M is an MCA [9]. By Lemma 1, we only need to prove that M is a -LA, i.e., for any two distinct t-way interactions and , where and . Next, we distinguish the following cases.

Case 1. and

In this case, because A is a -LA, , as A is part of M.

Case 2. and or and

When and , if , then . Thus, . If , then must be included by rows of , where ; however, it must not be included by any row of A. Clearly, must be included by some rows of A. Consequently, . When and , the same argument can prove the conclusion.

Case 3. and

Clearly, holds whenever . If , then , which implies that . If , then and must be included by some rows for a certain , where . Because B is a -LA, , which implies . □

More generally, we have the following construction.

Construction 5.

Let and . If a -LA, -LA, a -LA and -LA exist, then a -LA exists, where .

Proof.

We begin with a -LA, an array A that is on . Let and be two sets with and such that and , respectively. Suppose that , an array, is a -LA, which is on . For each row , of , add to obtain a k-tuple , . Then, we obtain a array from , denoted by B. Similarly, from a -LA, we obtain a array, denoted by C. For each pair , we construct k-tuple for each row of the given -LA. These tuples result in a array, denoted by D.

Denote , and . We claim that F, an array, is a -LA which is on .

Clearly, F is an MCA . To prove this assertion, we only need to demonstrate that for any two distinct t-way interactions and . By similar argument as the proof of Construction 4, we can prove the conclusion except for the case where and , , and . In this case, and are only included by some rows of D. If , then . Consequently, , which implies that by the construction of D. It is a contradiction with being a -LA. The proof is completed. □

4.2. Constructions and Existence of Optimal -LA

Let . An array A is called if for any t-way interaction and for any t-way interaction . If an optimal -LA with exists, then the following condition must be satisfied.

Lemma 7.

Let . If A is an optimal -LA with . Then, A is an .

Proof.

Let A be the given optimal -LA with . Then, A is an MCA by Lemma 1. Because , we have for any t-way interaction . It follows that for any t-way interaction of A from the definition of -LA, where . Hence, A is an , as desired. □

Clearly, an is not always a -LA. Next, we present a special case of , which produces optimal -LAs. First, we introduce the notion of mixed orthogonal arrays (MOAs).

An MOA, or MOA is an array with entries in the ith column from a set of size such that each sub-array contains each t-tuple occurring an equal number of times as a row. When , an MOA is merely an orthogonal array, denoted by OA.

The notion of mixed or asymmetric orthogonal arrays, introduced by Rao [36], have received significant attention in recent years. These arrays are important in experimental designs as universally optimal fractions of asymmetric factorials. Without loss of generality, we assume that . By definition of MOA, all t-tuples occur in the same number of rows for any sub-array of an MOA. This number of rows is called index. It is obvious that indices exist. We denote it by . If for any , then an MOA is termed as a pairwise distinct index mixed orthogonal array, denoted by PDIMOA. Moreover, if for a certain holds, then it is termed as . It is clear that in the definition of .

Example 2.

The transpose of the following array is a .

□

The following lemma can be easily obtained by the definition of ; therefore, we omit the proof herein.

Lemma 8.

Suppose that . If A is a , then and , where and .

Lemma 9.

Let . If a PDIMOA exists, then a -LA exists. Moreover, if , then the derived -LA is optimal.

Proof.

Let A be a PDIMOA. Clearly, A is an MCA. By Lemma 1, we only need to prove that implies , where and are two t-way interactions. In fact, if , then , which contradicts the definition of a PDIMOA. The optimality can be obtained by Theorem 1. □

We construct an optimal -LA with in terms of . First, we have the following simple and useful construction for . A similar construction for MOAs was first stated in [37].

Construction 6.

Let and . If a exists, then a also exists.

Proof.

Let A be with . We can form an array by replacing the symbols in by those of . It is easily verified that is the required . □

The following construction can be obtained easily; thus, we omit its proof.

Construction 7.

Let and . If both a and a exist, then a exists. In particular, if both a and an OA exist, then a exists.

Next, some series of optimal mixed-level -LAs are presented. First, we list some known results for later use.

Lemma 10.

[38] An OA exists for any integer .

The existence of s is determined completely by the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

Let . A exists if and only if for .

Proof.

The necessity can be easily obtained by Lemma 8. For sufficiency, we write for . Clearly, and for . We list all t-tuples from to form an MOA, which is also a . Apply Construction 7 with an OA given by Lemma 10 to obtain the required . □

More generally, we have the following results.

Theorem 3.

Let and , where , . Then, a exists.

Proof.

Let . Then, , where . By Theorem 2, a with exists. Apply Construction 6 to obtain a as desired. □

Theorem 4.

Let with . Then, an optimal -LA exists.

Proof.

First, we construct a array : , where and ; and for .

We prove that A is an optimal -LA. Optimality is guaranteed by Theorem 1. It is clear that A is . Consequently, and , where . It is clear that and . We only need to prove . In fact, by construction, for a certain but , where , which implies . Thus, A is a -LA by Lemma 1. □

The following example illustrates the idea in Theorem 4.

Example 3.

The transpose of the following array is an optimal -LA

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Theorem 5.

Let with . Then, an optimal -LA exists.

Proof.

First, we construct a array as follows:

When , let be a array with for and be an arbitrary element for with . Let and . It is easy to prove that M and N are the required arrays if and , respectively. □

The following results need the notion of a Latin square. A Latin square of order n is an array of n symbols in which each symbol occurs exactly once in each row and in each column. The diagonal of such a square is a set of entries that contains exactly one representative of each row and column, respectively. A transversal is a diagonal in which none of the symbols are repeated. For , there exists a Latin square of order n with n distinct transversals [39].

Theorem 6.

Let and . Then, an optimal -LA exists.

Proof.

Let with , where . For , a latin square of order w with w disjoint transversals, denoted by , exists. We take each of the w disjoint transversals from as a column to form a array , which, clearly, is also a Latin square. Let . The permutation is applied to the columns of L to obtain a new array denoted by . If L is a Latin square of w, then are also Latin squares of order w. The corresponding columns of and for have no common symbols.

Let be a array. It is easy to verify that A is a -LA. For each part of A, we can construct a array of the form . Next, juxtapose these resultant arrays to obtain a array , which is easily verified to be a -LA. Continue this process until the array B can be obtained. Clearly, B is a -LA.

Let . Suppose C is a array with entries from , where . Write ; if , if . It is easy to verify that is the required array. □

The following theorem considers the case .

Theorem 7.

Let be a positive integer. Then an optimal -LA exists.

Proof.

Let . We only need to construct a -LA, A, because is the required array. As , the number of occurrences of 0, 1 should be at least 2. It is easy to prove that all the different column vectors of length v with entries from form the -LA as desired. Thus, all that remains is to calculate the number of all the different column vectors. Write x and y as the number of 0s and 1s in a column vector of length v, respectively. Clearly, and . Because there exist x positions with 0s, the number of different column vectors is . Consequently, the number of all the different column vectors is . □

5. Concluding Remarks

LAs can be used to generate test suites for combinatorial testing and identify interaction faults in component-based systems. In this study, a lower bound on the size of -LAs with mixed levels was determined. In addition, some constructions of -LAs were proposed. Some of these constructions produce optimal locating arrays. Based on the constructions, some infinite series of optimal locating arrays satisfying the lower bound in Lemma 2 were presented. Obtaining new constructions for mixed-level -LAs and providing more existence results are potential future research directions.

Author Contributions

Computing and writing, C.S. and T.T., writing, literature survey and editing, H.J. and T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China No. 11301342 and Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Grant No. 17ZR1419900.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Colbourn, C.J.; Martirosyan, S.S.; Mullen, G.L.; Shasha, D.E.; Sherwood, G.B.; Yucas, J.L. Products of mixed covering arrays of strength two. J. Comb. Des. 2006, 14, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D.R.; Kacker, R.N.; Lei, Y. Introduction to Combinatorial Testing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, C.; Leung, H. A survey of combinatorial testing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2011, 43, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourn, C.J. Combinatorial aspects of covering arrays. Le Matematiche (Catania) 2004, 58, 121–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, K.; Colbourn, C.J. Two-stage algorithms for covering array construction. J. Comb. Des. 2019, 27, 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, N.J.A. Covering arrays and intersecting codes. J. Combin. Des. 1993, 1, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.M.; Dalal, S.R.; Parelius, J.; Patton, G.C. The combinatorial design approach to automatic test generation. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1996, 13, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.M.; Dalal, S.R.; Fredman, M.L.; Patton, G.C. The AETG system: An approach to testing based on combinatorial design. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1997, 23, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Shi, C.; Wang, C.M.; Yan, J. Mixed covering arrays of strength three with few factors. J. Stat. Plan. Infer. 2011, 141, 3640–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.; Stardom, J.; Stevens, B.; Williams, A. Covering arrays with mixed alphabet sizes. J. Comb. Des. 2003, 11, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, G.B. Optimal and near-optimal mixed covering arrays by column expansion. Discrete Math. 2008, 308, 6022–6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Colbourn, C.J.; McClary, D.W. Locating and detecting arrays for interaction faults. J. Combin. Optim. 2008, 15, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaco, A.N.; Colbourn, C.J.; Syrotiuk, V.R. Locating arrays: A new experimental design for screening complex engineered systems. SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 2015, 49, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, R.; Mehari, M.T.; Colbourn, C.J.; Poorter, E.D.; Syrotiuk, V.R. Screening interacting factors in a wireless network testbed using locating arrays. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 10–14 April 2016; pp. 650–655. [Google Scholar]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Syrotiuk, V.R. Coverage, Location, Detection, and Measurement. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Chicago, IL, USA, 11–15 April 2016; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Fan, B.L.; Horsley, D. Disjoint spread systems and fault location. SIAM J. Discrete Math. 2016, 30, 2011–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Tang, Y.; Yin, J.X. The equivalence between optimalb detecting arrays and super-simple OAs. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2012, 62, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Colbourn, C.J.; Yin, J.X. Optimality and constructions of locating arrays. J. Stat. Theory Pract. 2012, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Fan, B.L. Locating one pairwise interaction: Three recursive constructions. J. Algebra Comb. Discrete Struct. Appl. 2016, 3, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T.; Kojima, H.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsuchiya, T. Finding minimum locating arrays using a SAT solver. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Tokyo, Japan, 13–17 March 2017; pp. 276–277. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, T.; Kojima, H.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsuchiya, T. Finding minimum locating arrays using a CSP solver. Fundam. Inform. 2020, 174, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamoto, T.; Kojima, H.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsuchiya, T. Locating a Faulty Interaction in Pair-wise Testing. In Proceedings of the IEEE 20th Pacific Rim International Symposium on Dependable Computing, Singapore, 18–21 November 2014; pp. 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lanus, E.; Colbourn, C.J.; Montgomery, D.C. Partitioned Search with Column Resampling for Locating Array Construction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Xi’an, China, 22–23 April 2019; pp. 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, S.A.; Sarkar, K.; Colbourn, C.J.; Syrotiuk, V.R. Separating Interaction Effects Using Locating and Detecting Arrays. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Combinatorial Algorithms, Singapore, 16–19 July 2018; pp. 349–360. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Kitamura, T.; Choi, E.H.; Tsuchiya, T. A Satisfiability-Based Approach to Generation of Constrained Locating Arrays. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops, Vasteras, Sweden, 9–13 April 2018; pp. 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Tsuchiya, T. Constrained locating arrays for combinatorial interaction testing. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1801.06041. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Tsuchiya, T. Deriving Fault Locating Test Cases from Constrained Covering Arrays. In Proceedings of the IEEE 23rd Pacific Rim International Symposium on Dependable Computing (PRDC), Taipei, Taiwan, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, T.; Kojima, H.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsuchiya, T. Using simulated annealing for locating array construction. Inf. Soft. Tech. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Kéri, G.; Rivas Soriano, P.P.; Schlage Puchta, J.C. Covering and radius-covering arrays: Constructions and classification. Discret. Appl. Math. 2010, 158, 1158–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, Y.H. The Existence of SSOAλ(2,5,v)′s. Master’s Thesis, Soochow University, Suzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, S. On simple and supersimple transversal designs. J. Comb. Des. 2000, 8, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, C.M. Optimum detecting arrays for independent interaction faults. Acta Math. Sin. Eng. Ser. 2016, 32, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Yin, J.X. Existence of super-simple OAλ(3,5,v)’s. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2014, 72, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yin, J.X. Detecting arrays and their optimality. Acta Math. Sin. Eng. Ser. 2011, 27, 2309–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, G. K-Propriétés dans des Tableaux de N Colonnes; Cas Particulier de la K-Surjectivité et de la K-Permutivité. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Paris, Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.R. Some Combinatorial Problems of Arrays and Applications to Design of Experiments. A Survey of Combinatorial Theory; Srivastava, J.N., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.Z.; Ji, L.J.; Lei, J.G. The Existence of Mixed Orthogonal Arrays with Four and Five Factors of Strength Two. J. Combin. Des. 2014, 22, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayat, A.S.; Slone, N.J.A.; Stufken, J. Orthogonal Arrays; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Dinitz, J.H. The CRC Handbook of Combinatorial Designs; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).