Abstract

Control charts are commonly used tools that deal with monitoring of process parameters in an efficient manner. Multivariate control charts are more practical and are of greater importance for timely detection of assignable causes in multiple quality characteristics. This study deals with multivariate memory control charts to address smaller shifts in process mean vector. By adopting a new homogeneous weighting scheme, we have designed an efficient structure for multivariate process monitoring. We have also investigated the effect of an estimated variance covariance matrix on the proposed chart by considering different numbers and sizes of subgroups. We have evaluated the performance of the newly proposed multivariate chart under different numbers of quality characteristics and varying sample sizes. The performance measures used in this study include average run length, standard deviation run length, extra quadratic loss, and relative average run length. The performance analysis revealed that the proposed control chart outperforms the usual scheme under both known and estimated parameters. An application of the study proposal is also presented using a data set related to Olympic archery, for the monitoring of the location of arrows over the concentric rings on the archery board.

1. Introduction

Statistical process control (SPC) is a collection of useful tools that handle the variations occurring in process parameters. It helps us to monitor any irregularities happening in the process behavior with respect to parameters of concern such as location and dispersion. It is comprised of many useful tools including a cause-and-effect diagram, check sheet, control chart, histogram, pareto chart, scatter diagram, and flowchart (stratification). A combination of all such tools is formally known as an SPC took-kit. All of these SPC tools have their own specific objectives, for example, the cause-and-effect diagram identifies the possible causes for a problem and carries out sorting of ideas into useful categories, the check sheet is used to collect and analyze data, the pareto chart filters the more significant factors, the scatter diagram shows the relationships among different factors in the process, and the flow chart separates the data gathered from various sources. The control chart gets the highest rank in the SPC tool-kit because of its ability to study/analyze process abnormalities over time. These abnormalities cause variations in the process output that may lead to deterioration of the process quality. These variations may be natural (random) or un-natural (systematic) and control charts have the ability to differentiate between these two types of variations. The natural variations are acceptable to the process, but un-natural variations are of concern to the process engineers, as delay in their identification may result into huge loss to the process owners.

In real process scenarios, we come across different quality characteristics of interest that need our attention in a process. This leads us to simultaneous handling of such variables in a multivariate set up, named multivariate SPC. The multivariate control charts are very important tools in timely identification of any changes in multiple quality characteristics of interest in a process. In the recent decades, multivariate control charts received attention because of advancements in computational facilities used as main barriers in their implementation. The three popular categories of univariate control charts (Shewhart, exponential weighted moving average (EWMA), and cumulative sum (CUSUM)) are equally effective in multivariate setup, namely, multivariate Shewhart (the well know Hotelling’s T2, [1,2]); multivariate EWMA, that is, MEWMA ([3,4]); and multivariate CUSUM, that is, MCUSUM ([5,6,7]).

The literature on multivariate SPC control charts spans multiple directions that might be of concern in process monitoring such as detections of shifts in mean vector and variance covariance matrix, interpretations of out of control signals, principal components, regression adjustments and so on. The authors of [8] discussed multivariate charts for the monitoring of individual observations. The study of [3] gave a review on multivariate control charts. Other studies [5,6,9] have extended the ideology of the study of [10] towards designing quality control charts with the scope of monitoring two or more related characteristics jointly. The work of [9] suggested the use of simultaneously classical CUSUM control charts for related observations. The authors of [5] recommended two multivariate CUSUM control charts for jointly monitoring of related characteristics. First, the multivariate CUSUM chart converts the related characteristics into scalar quantity, and then formulates the structure of the control chart, while the second CUSUM procedure forms a CUSUM vector directly from the observations. Later, the work of [6] also recommended two multivariate CUSUM control charts, name and . The input statistic of the control chart is based on a quadratic form using a vector of accumulated observations. The control chart uses the scalar quantity computed through a quadratic form based on the current observation vector.

The work of [11] extended the idea of [12] for related quality characteristics, and proposed a multivariate exponential weighted moving average (MEWMA) control chart. Some of the modification in multivariate classical control charts can be seen in [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] and the references therein. The authors of [24] extended the study of [25] known as a homogeneously weighted moving average (HWMA) control chart for the multivariate setup, and named it the MHWMA control chart. The HWMA and MHWMA control charts assign a specific weight to the current observation, and the remaining weight is equally assigned to the rest of the observations for effective process monitoring.

The remaining part of the article is arranged as follows: Section 2 describes the preliminaries and some existing multivariate control charts available; Section 3 provides the charring structure of proposed multivariate control chart; Section 4 provides performance measures and evaluation of the proposed chart and estimation effects, along with a comparative analysis with some existing charts; Section 5 provides an illustrative example that demonstrates the implementation of the proposal; and finally, Section 6 concludes the study and provides some future recommendations.

2. Preliminaries and Existing Multivariate Control Charts

Let be a dimensional vector having multivariate normal distribution with (mean vector) and (variance-covariance matrix), written as follows: . Here, is mean vector and is a matrix. For our study purposes, we will use for the known mean vector and for the known variance–covariance matrix. The , , are defined, respectively, as follows:

Let be the sample matrix consisting of as the () observation of the () quality charectersitic on the () sample. The multivariate data structure can be presented as given in Table A1 (Appendix A).

Let and be the dimensional sample mean vector and sample variance–covariance matrix and), respectively. These are defined as follows:

, , for and

Analogue with , where

In practice, when and are unknown, both are estimated from in-control Phase I for each sample of sample size as follows:

where and . The diagonal elements of are means of sample variances associated to quality characteristics and off-diagonal are means of sample covariances, obtained from samples. It is to be missioned that refers to the mean vector of a particular sub-group, while refers to overall the mean vector of all the m sub-groups.

We provide brief details of some common multivariate chats and propose a new control chart (for known and unknown parameters) for the mean vector.

2.1. Existing Multivariate Charts

The following section expresses the charting structures of existing multivariate control charts including /Hotelling’s , , , , and charts by [2,5,6,11,24], respectively.

2.1.1. and Hotelling’s Charts

The Shewhart multivariate process control chart based on the weighted Mahalanobis distance of the sample mean from the process mean is (cf. [2]) as follows:

As , the control charting statistics (1) follows distribution (Chi-square probability distribution with t degrees of freedom), which gives an out-of-control signal, if, where . ( is the -dimensional upper percentage point of the distribution) is a specified control limit. The study of [1] proposed the special case of (1) to monitor sample point as for. By replacing and with and , respectively, the expression (1) becomes the following:

Under the assumption that the samples are independent and the joint distributions of the variables is the multivariate normal, follows times distribution with degree of freedom and (cf. [26]). Expression (2) becomes at , which is called Hotelling’s chart for individuals (cf. [7]). The Hotelling’s chart gives an out-of-control signal if , where .

2.1.2. Chart

The study of [5] proposed two multivariate CUSUM charts. One of these charts (the superior one) is based on the charting statistics:

where , , , and . The MCUSUM chart gives an out-of-control alarm if

where is chosen to achieve a desired value of in-control average run length (ARL).

2.1.3. Chart

The work of [6] proposed two invariant multivariate CUSUM charts. Both charts are based on the quadratic forms of the mean vector and can be distinguished with respect to the accumulation (i.e., the sum).

Chart: The accumulates the vectors and then generates the quadratic forms, while in, initially, the quadratic form is produced for each , and then these are accumulated at a later stage.

where the number of subgroups since the most recent renewal (i.e., zero value) of the CUSUM. As can be written as

the vector represents the difference between the accumulated sample average and the target mean. Therefore, at time, the multivariate process mean may be estimated as . The norm of is a measure of the distance between the estimate and the target, mathematically defined as follows:

A multivariate control chart can be constructed by defining chart as

and

The multivariate process thorough this multivariate CUSUM chart will be declared as out-of-control if, where is chosen to achieve a desired value of in-control ARL.

Chart: In the chart, if accumulation function is applied after taking the square of the distance of each sample mean from , it results in a new structure. As a result, we evaluate of the sample mean as follows:

having a with degrees of freedom (on-target) and a non-central (off-target). A one-sided CUSUM structure is given as follows:

where = 0. An out-of-control signal is alarmed if, where is set according to a desired in-control ARL.

2.1.4. Chart

The work of [11] developed the multivariate EWMA () chart to quickly detect shifts in the process mean vector from the target vector , and its statistic is defined as follows:

where, initially, , of the smoothing constant with , (usually in practice ), and is the identity matrix (cf. [11]). The process gives an out-of-control signal in chart when

where is selected to get the chosen in-control average run length. The term is an asymptotic variance–covariance matrix (as) defined as , while is the time varying variance–covariance matrix. Symbolically, for the chart for asymptotic and time varying cases, we may write as and , respectively. It is to be noted that, when, the chart is converted to Hotelling’s chart. (cf. [11]).

2.1.5. Chart

The study of [24] proposed a multivariate homogeneously weighted moving average () chart for the mean vector. The plotting statistic of chart is given as follows:

where represents the sample average of the previous information up to and including the observation, . For the case of equal , the will be in Equation (12).

The chart indicates a signal if

where and are set based on the in-control average run length (), and refers to the variance–covariance matrix defined as follows:

If = 1, the monitoring statistic in Equation (12) becomes and the variance of in Equation (14) becomes () and (). Further details can be seen in [24].

3. The Proposed Control Chart for Subgroups

The proposed multivariate homogeneous weighted moving average () assigns a certain weight to current sample and the remaining weight is uniformly distributed among the previous samples. The charting statistic of this chart, for subgroups of size n, is defined as follows:

This can also be extended as follows:

where denotes the sample mean vector for sample, and is the mean vector based on the means of preceding samples. Initially, the value of is set equal to the in-control sample mean vector, that is, . As mentioned earlier, the quality characteristic. So, it is a well-known fact that the distribution of the sample mean vector is also normal with and , that is, (cf. [27]). The process signals in chart when

where is set according to a pre-specified in-control, and is the variance–covariance matrix at time defined as follows:

If = 1, we have (cf. Equation (15)), and the variance of in Equation (14) becomes () and (). The mean and variance under in-control situation are derived in the Appendix A.

Estimation of Unknown Parameters for MHWMAP Chart for Subgroups

According to [4], the sampling distribution of charting statistics of a chart should be accounted for variation because it may seriously affect the in-control and out-of-control performance. The denial of this variation may cause a significant increase in the number of false alarms in the case of small sample size data in Phase I. The estimation error is inversely proportional to sample size of Phase I data ([4]).

As in the previous Section 2.1, we usually assume normality and known parameters such as mean vector and variance–covariance matrix (cf. [24]). However, these parameters, that is, and , are not always known in practice, and hence estimation is used, which ultimately affects charts’ performance. In this section, we study the performance of the MHWMA chart under the estimation case. When the and are unknown, they are usually estimated based on subgroup (of a fixed size) from an in-control, where and. The estimators of and are and. The study of [27] showed that the in-control estimator of the mean vector and the matrix.

In this study, we discuss two cases, namely Case I and Case II:

Case I: The values of and are known and the control limits for Case I are defined in (19);

Case II: The values of and are estimated from Phase I as . and (derived in Appendix A–III). On the basis of and , the process gives an out-of-control signal in chart when

where is chosen to achieve a desired in-control performance measure, and is the covariance matrix at time point defined as follows:

The estimated mean and estimated variance under the in-control situation are derived in the Appendix A.

4. Performance Evaluations and Comparisons

The current section comprises of a set of performance measures that are based on the run length observations. These performance measures, namely, average run length (), standard deviation of the run length extra quadratic loss (), relative average run length (), and performance comparison index (), are analyzed to examine and compare the detection capability of different charts. The studies the performance of a chart at each shift separately, while, , and deal with the overall shift range. The term δ can be defined as, where is out-of-control mean vector (cf. [24]). These measures are defined as follows.

Average Run Length (ARL) is the expected number of points prior to a point indicates an out-of-control signal by the chart. The and are two types of ARL mentioned as the in-control and out-of-control situation of a process, respectively. ARL0 and ARL1 are the average number of samples desired to get a false alarm in an in-control situation and a shift in an out-of-control situation, respectively. , a chart with a lower is considered as an efficient chart relative to another chart (cf. [28]). The best chart acquires a lower number of samples to detect the shift in the minimum ARL value. ARL has been used as a performance measure in many research articles such as [29,30].

Along with , we have also reported standard deviation of run length () to assess the behavior of the run length distribution (cf. [31]), which measure of the spread in the run length around its center.

Extra Quadratic Loss (EQL) is a measure used to assess the overall ability of a chart (cf. [32,33,34]). Mathematically, . The distribution of is uniform with density function over the entire shift range (cf. [28,35]). The probability distribution of (other than normal distribution) has a partial impact on EQL-based performance of charts (cf. [36]). The best performing chart has a minimum EQL value as compared with any competing chart. A control chart exhibiting superior EQL performance under uniform distribution of shift also offers superior performance under non-uniform cases.

Relative Average Run Length (RARL) inspects the overall performance of a chart relative a benchmark chart (cf. [33]). Mathematically, it is defined as , where and are the ARL of a specific chart and the standard charts, respectively, at. For a standard chart, the RARL is equal to 1.

Performance Comparison Index (PCI) evaluates the performance of control charts based on the EQL. It is defined as the ratio of EQL value of a specific chart to EQL value of optimum chart (cf. [37]). Analogous with RARL, PCI may also get two values: PCI = 1 and PCI > 1 for best and competing charts, respectively. Mathematically, . As RARL and PCI have similar interpretations, they may be used instead of each other. One may see more details of these performance measures in [32,37] and the references therein.

4.1. Monte Carlo Simulation Procedure

The Monte Carlo simulation technique is used to get am estimated solution of certain mathematical and statistical complixities. The literature on this simulation technique can be seen in [38,39,40], and the references therein. In order to find the values ARLs and SDRLs, a Monte Carlo simulation study based on 50,000 replications is carried out in R language (cf. [41]) by setting; ; ; and . For a suitable number of Monte Carlo simulation iterations in quality control, one may see [40,42,43]. The aforementioned computational methods are quite popular for control charts (cf. [44,45]). The calculation technique is described as follows:

- Generate the random samples from multivariable normal distribution and compute the values of the charting statistics Hotelling’s,, , , , and .

- Establish the control limits for all charting statistics.

- Calculate the values of ARL and SDRL for each charting statistics at changing shift values (0.50, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3) for fixed.

In order to compute other performance measures, we applied famous numerical integration procedures (such as Simpson/Trapezoidal methods) through these steps.

- Multiply ARL with and inverse of range of values as .

- Get by integrating the result (obtained in step i) over range using the Simpson or Trapezoidal integration technique.

- Take the ratio of the s of a specific to optimum/standard charts and multiply with the inverse of entire range of .

- Calculate by integrating the output over range.

- Get PCI by taking the ratio of of a particular chart to the optimum/standard chart.

4.2. Performance Analysis and Comparisons

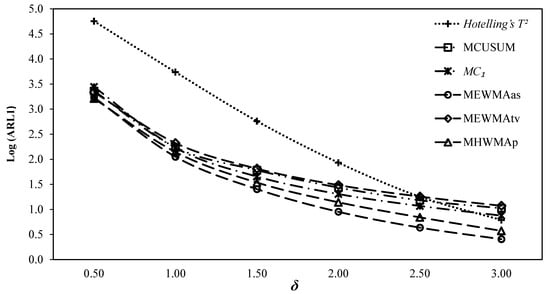

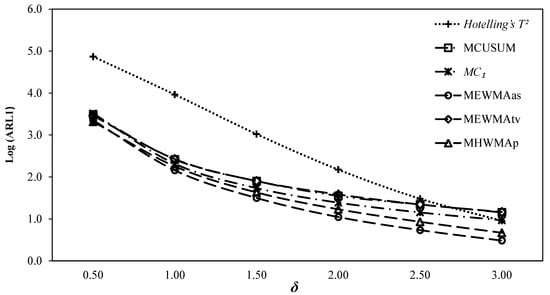

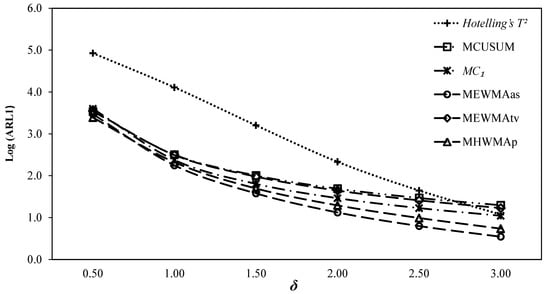

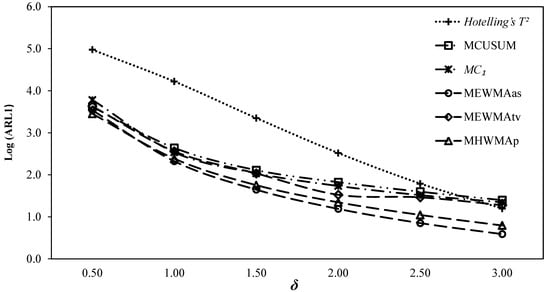

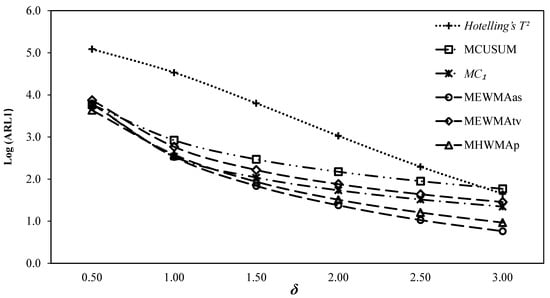

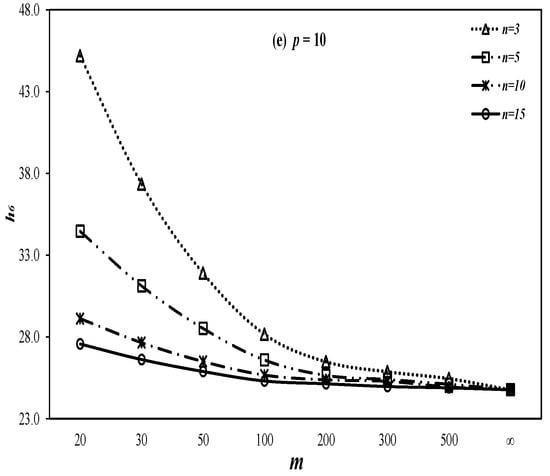

This section provides a comparative analysis of understudy and proposed charts using two methods, namely, (i) point to point shifts approach and (ii) entire shift range approach. The first approach is used to calculate ARL values, while the second is used to obtain the values of EQL, RARL, and PCI measures. The ARL values are obtained for understudy charts and the values are plotted along with values for a better comparative view (cf. Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). On the basis of the ARL1 values, we calculated the cumulative , and values, namely, , and , respectively, and the results are given in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. On the basis of Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, we have also provided the superiority order understudy charts at varying choices of and δ in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Average run length (ARL) comparisons for. MEWMA, multivariate exponential weighted moving average; MHWMA, multivariate homogeneously weighted moving average; MCUSUM, multivariate CUSUM.

Figure 2.

ARL comparisons for.

Figure 3.

ARL comparisons for.

Figure 4.

ARL comparisons for.

Figure 5.

ARL comparisons for.

Table 1.

Cumulative extra quadratic loss (EQL) values for different charts. MEWMA, multivariate exponential weighted moving average; MHWMA, multivariate homogeneously weighted moving average; MCUSUM, multivariate CUSUM.

Table 2.

Cumulative relative average run length (RARL) values for different charts.

Table 3.

Cumulative performance comparison index (PCI) values for different charts.

Table 4.

Superiority order of multivariate charts at varying .

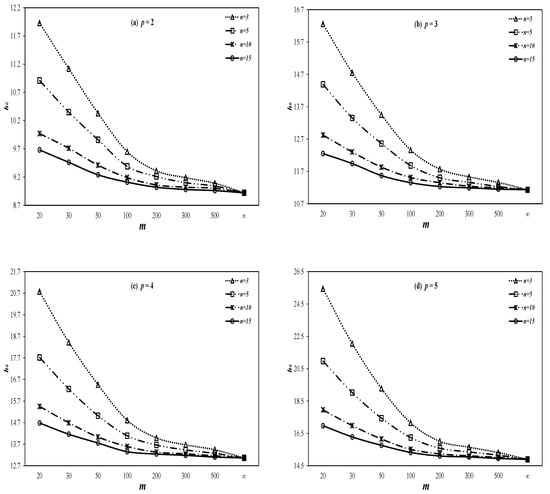

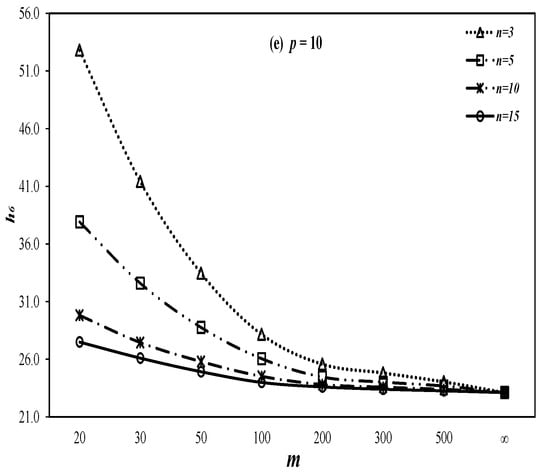

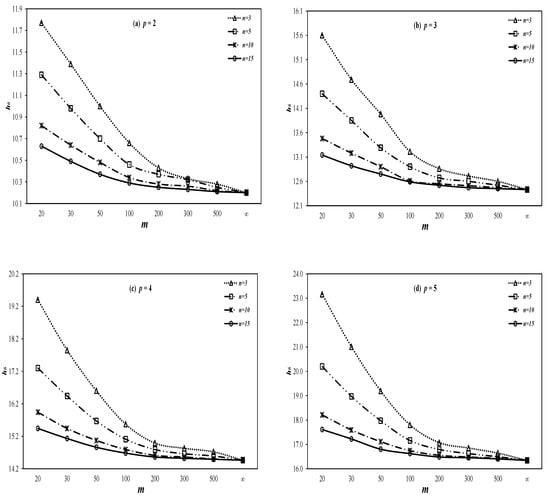

In order to study the estimation effect of parameters on and, the related results are provided in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively. For this, we produced the and values at );. For the suitable choice of subgroup size , the literature may be recommended in this direction, for example, see [46,47] and the references therein. It is to be noted that the estimated . and results converge to the results for the known parameter if .

Table 5.

Estimation effect on ARL0 values.

Table 6.

Estimation effect on SDRL0 values.

The best performing chart will exhibit the lowest ARL curve, which means that a lower number of samples are required for a shift in the detection.The findings are summarized as follows.

CASE I: Analysis under known parameters

It can be observed from the ARL curve for (cf. in Figure 1) that and charts outperform, , , and Hotelling’s charts. The chart has smaller ARL values at , and larger values at than the chart. The chart has a smaller ARL value than at , and vice versa at. The chart has smaller values than the and charts, respectively, at , while the traditional Hotelling’s chart has minimum ARL values at all values of.

Overall, it can be observed that the chart outperforms the other charts at small shifts, while the chart does with the increasing shift. The Hotelling’s chart exhibits the worst performance at the shift range of, while the other charts exhibit performance in between the best and worst charts. The above performance order based on the cumulative performance measures provided in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 for can be observed in Table 4.

It can be observed from the ARL curve for given in Figure 2 that the and charts outperform,, , and Hotelling’s charts. The chart has smaller ARL values at , and larger values at than the chart. The chart has a smaller ARL value than at. The chart has smaller values than the and charts, respectively, at and the and charts, respectively, at. The usual Hotelling’s chart has minimum values at all values of.

Overall, it can be observed that the . chart exhibits the best performance compared with the other charts at small shifts, while the chart does with the increasing shift. The Hotelling’s chart exhibits the worst performance at the entire shift range, while the other charts exhibit performance in between the best and worst charts. The above performance order based on the cumulative performance measures provided in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 for can be observed in Table 4.

It can be observed from the ARL curve for given in Figure 3 that the and charts outperform, , , and Hotelling’s charts. The chart has smaller ARL values at , and larger values at than the chart. The chart has smaller ARL values than the and charts, respectively, at. The chart has smaller values than the and charts, respectively, at and the and charts, respectively, at. The usual Hotelling’s chart has minimum values at all values of.

Overall, it can be observed that the chart exhibits the best performance compared with the other charts at small shifts, while the chart does with the increasing shift. The Hotelling’s chart exhibits the worst performance at the entire shift range, while the other charts exhibit performance in between the best and worst charts. The above performance order based on the cumulative performance measures provided in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 for can be observed in Table 4.

It can be observed from the ARL curve for given in Figure 4 that the and charts outperform, , , and Hotelling’s charts. The chart has smaller values at , and larger values at than the chart. The chart has smaller ARL values than the and charts, respectively, at. The chart has smaller values than the and charts, respectively, at and the and charts, respectively, at. The usual Hotelling’s chart has minimum ARL values at all values of.

Overall, it can be observed that the chart exhibits the best performance compared with the other charts at small shifts, while the chart does with the increasing shift. The Hotelling’s chart exhibits the worst performance at the entire shift range, while the other charts exhibit performance in between the best and worst charts. The above performance order based on the cumulative performance measures provided in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 for can be observed in Table 4.

It can be observed from the ARL curve for given in Figure 5 that performs better than the, , and charts at , respectively, but shows inferior performance o the chart at , respectively. The chart shows better performance than the and charts at. The chart shows better performance than the . and charts, respectively, at and the charts, respectively, at. The usual Hotelling’s chart has minimum ARL values at all values of.

Overall, it can be observed that the chart exhibits the best performance compared with the other charts at small shifts, while the chart does with the increasing shift. The Hotelling’s chart exhibits the worst performance at the entire shift range, while the other charts exhibit performance in between the best and worst charts. The above performance order based on the cumulative performance measures provided in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 for can be observed in Table 4.

Some specific findings regarding Case I are listed below:

- The values of the proposed and other competing charts decrease as the value of decreases, and vice versa. For example, at and 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, the values of chart are 24.80, 27.55, 29.61, 31.56, and 37.87, respectively. This reveals that the detection ability of charts improves as the number of variables increases in multivariate monitoring. A similar type of behavior can be observed for other charts (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

- The chart exhibits the best performance at small followed by. For example, at, the values of chart are 3.44, 3.70, 3.95, and 4.73, while those of the chart are 3.56, 4.56, 4.29, and 5.54 for 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. At, the values of chart are 5.10, 5.72, 6.38, and 6.84, while those of the chart are 5.23, 5.82, 6.25, and 6.65 for 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

- The Hotelling’s chart exhibits the most inferior performance among all charts. For example, for and , the for Hotelling’s chart, while 28.8, 31.3, 25.3, 28.1, and 24.8 for , , , , and charts, respectively. Similarly, for and , the for Hotelling’s chart, while 43.2, 43.9, 44.3, 44.1, and 37.87 for , , , , and charts, respectively. The inferiority of Hotelling’s chart can be observed for other choices of (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

CASE II: Analysis under estimated parameters

In order to examine the estimation effect of unknown parameters, we have observed that the and values are affected because of the control limits based on estimated values of parameters. The detailed results about the estimation effect of parameters on and values (at varying choices of, , , and ), provided in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively, are given as follows:

- The values are inversely related with the value of in the case of estimated parameters. This means that, as the number of variables increases in the multivariate set up, the values decrease. For example, for, , and , the 91.12, 65.51, 48.25, 36.36, and 8.87 at 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10, respectively (see Table 5). We may also oberserv behavior of the 115.34, 83.32, 64.08, 51.48, and 19.13 at 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10, respectively (see Table 6).

- The values based on estimated parameters decrease as the value of smoothing parameter increases. This means that the in-control moved downward as . For example, at the = 132.80, 147.64, 160.42, 167.85, 173.39, and 178.77 at respectively (see Table 5). Similarly, we may observe the results at , where the = 131.47, 163.29, 198.09, 212.99, 222.16, and 229.72 at respectively (see Table 6).

- As the sample size and/or sub-group size increase, the false alarms produced by chart decrease, which means that the estimated version of converges to as. For instance, for, as increases from 3 to 15, the increases from 110.26 to 169.61.72 at ; as increases from 30 to 500, the increases from 110.26 to 187.72 at (see Table 5). Similar behavior of the results can be observed as , because, if increases from 3 to 15, the increases from 122.86 to 145.34 at ; if increases from 30 to 500, the increases from 122.86 to 155.36 at (see Table 6).

The Corrected Control Limits: As we observed in Case II above, values are affected owing to the estimation effects in our control limits. Consequently, it is necessary to revise the control limits’ coefficient in order to attain the desired. For our study purposes, we have worked out the corrected control limits coefficients for our proposed chart at various choices of,), and ). The resulting coefficients are provided in Table 7 at some useful combinations of , . Moreover, we have also produced some selective graphs of the control limits’ coefficient versus at various choices of , , and . The resulting graphs are provided in Figure 6 and Figure 7. It may observed from these tables and figures that the corrected limits get closer to the known limit (limit of the case of known parameter) with the increase in either or or both of these quantities.

Table 7.

Corrected control limits coefficients h_6.

Figure 6.

Control limit curves of proposed chart under estimated parameters with λ = 0.1.

Figure 7.

Control limit curves of proposed chart under estimated parameters with λ = 0.2.

Case when the parent distribution is heavy tailed: Throughout the paper so far, we have assumed that the variables of interest follow a multivariate normal distribution. This subsection provides the effect of deviation from normality in terms of a heavy tailed distribution, that is, multivariate t-distribution. The in-control ARL values for the proposed chart under known parameters case are given in Table 8, where the data are generated from multivariate t-distribution with degrees of freedom. The table clearly shows that the ARL values of the proposed chart get close to 200 as we increase the value of , and finally implies . This is in line with the multivariate distributional theory that the multivariate T-distribution tends to multivariate normal distribution as . For the smaller values of , the ARLs are substantially smaller than 200, implying that the constants evaluated in Table 7 are not appropriate.

Table 8.

ARL values of MHWMA chart for multivariate T-distribution.

5. An Application

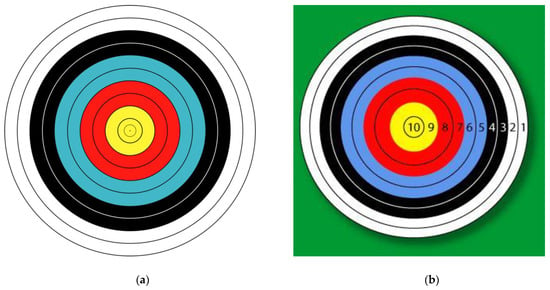

Illustrating the proposed control charts using a real dataset is common practice; see, for example, [48]. For illustration purpose in the current study, we used a data set related to Olympic archery, for the monitoring of location of arrows over the concentric rings on the archery board (cf. [7]). Target archery is the most standard form of archery directed by the World Archery Federation, in which participants shoot at stationary circular targets at varying distances. The size of the target varies and is usually measured as a 122 cm face for a distance of 70 m, all containing 10 concentric rings, representing different sectors to score. The outermost two rings (rings 1 and 2) are white, rings 3 and 4 are black, rings 5 and 6 are blue, rings 7 and 8 are red, and rings 9 and 10 (the innermost) are gold (cf. Figure 8a).

Figure 8.

Description of target archery.

The scoring criterion is as follows: we add up all the points based on the arrows hitting different rings as mentioned above. The innermost ring gets a score of 10 and the outermost ring gets a score of 1, and for the inner rings, the score gradually decrease from 10 to 1 (cf. Figure 8b). The first 72 shots in finishes of three arrows of the ranking round of a particular archer with 24 subgroups were collected when the process was working under in-control state (i.e., Phase I) in order to estimate the unknown parameters. We used these estimated values of parameters and computed trail control limits. By plotting the Phase I data on these trail control limits, we found the first six points out of the control limits (which means that the process was not in-control when these samples were collected). Hence, we discarded first six samples from our Phase I data and revised our estimates to compute revised control limits.

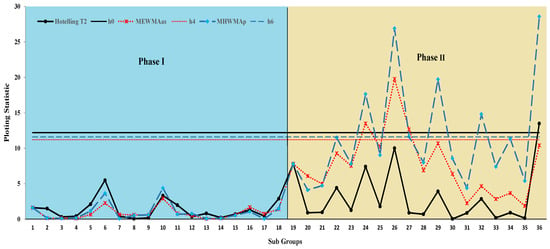

Now, we have 18 subgroups containing 54 shoots of the elimination round in Phase I, and another 18 additional subgroups consisting of 54 shoots of the elimination round with the same subgroup size, which were collected in Phase II. Setting in-control under Hotelling’s , the , and charts are made with , , , and , respectively. In order to demonstrate the application of study, we plotted the values of charting statistics (calculated from Phase I and Phase II data) of the Hotelling’s , , and charts against their respective control limits in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of proposed and existing chart under the target archery dataset.

From Figure 9, it can be observed that the Hotelling’s, , and charts are detecting an upward and downward shift in the process. The Hotelling’s chart indicates the first out-of-control signal at the last sample, while the chart triggers the first out-of-control signal at the 24th sample. The proposed chart detects the first out-of-control signal at the 24th sample (cf. Figure 9). Moreover, the Hotelling’s , , and proposed charts detect 1, 3, and 7 out-of-control signals (cf. Figure 9), respectively, which means that the proposed chart has better detection ability than the other charts. These results display the supremacy of the proposed chart against the competing charts, and these results are also consistent with the findings of the study.

The property of better detection ability of MHWMAp chart claimed in Section 5 has a strong connection with the findings of Section 4, where the superiority of the proposal is established based on RL properties. These properties are based on the repeated iterations from a theoretical model by fixing ARL0 at a specific level for all of the charts under investigation, in order to maintain uniformity in performance evaluation. The RL analysis is also carried out at varying shifts, and the resulting outcomes are presented in tabular and graphical forms (cf. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 and Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), where the study proposal exhibits a clear dominance over others. Therefore, the feature of better detection in our application leads to justified conclusions, which will be acceptable to practitioners and quality control engineers.

6. Summary, Conclusions, and Future Recommendations

In this study, we proposed a new weighting scheme to design an efficient structure for proposed multivariate homogeneous weighted moving average chart. We developed the control charting structure of the proposed chart along with some existing Hotelling’s,, , , and charts. We investigated the performance of all charts under different numbers of quality characteristics and varying sample sizes and perceived that the performance of charts improves as the number of variables increases in the monitoring of the multivariate process. Overall, the proposed chart exhibits the best performance and Hotelling’s chart shows the worst performance. The performance of the proposed chart is seriously affected by the usage of a small number of Phase I samples at the estimation stage. Moreover, the in-control performance of the proposed chart is inversely related to the increment in the number of variables and smoothing parameter.

The current study can be extended by using different sampling strategies including ranked set sampling, two phases sampling, and so on in multivariate control charting. Moreover, the current study may also be extended for different runs rules schemes of quality control. Last, but not least, the current study can be of potential use in manufacturing and services processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A., M.R., and S.A.; methodology, N.A. and S.A.; software, N.A. and S.A.; validation, M.A. and B.Z.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, M.R.; resources, M.A.; data curation, M.A. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, N.A., M.R., and B.Z.; visualization, S.A. and N.A.; supervision, M.R.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, grant number SB191047

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the referees for their valuable comments that helped to improve the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| X | Vector of multivariate variables |

| Mean vector | |

| Variance–covariance matrix | |

| Number of variables | |

| Multivariate normal distribution | |

| As the () observation of the () quality Charectersitic on the () sample | |

| sample mean vector | |

| sample variance–covariance matrix | |

| Known mean vector | |

| Known variance–covariance matrix | |

| Estimator of | |

| Estimator of | |

| Chi-qquare probability distribution with t degrees of freedom | |

| Control limit of Hotelling’s charts when and are used | |

| Plotting statistics of Hotelling’s chart when and are estimated | |

| Control limit Hotelling’s chart when and are used | |

| Distribution with degree of freedom and | |

| Charting statistic of chart | |

| Charting statistic of chart | |

| Constant of chart | |

| Plotting statistic of chart | |

| Vector forchart | |

| Number of subgroups | |

| Plotting statistic ofchart | |

| Control limit of chart | |

| Scalar observation for chart | |

| Plotting statistic of chart | |

| Control limit of chart | |

| Observations vector for the chart | |

| Vector of constant | |

| Identity matrix | |

| Plotting statistic of Chart | |

| Asymptotic variance-covariance matrix of Chart | |

| Control limit of Chart | |

| Observations vector for control chart | |

| Plotting statistic of control chart | |

| Inverse variance covariance matric for control chart | |

| Control limit of control chart | |

| Represents the variance of statistic when = 1 | |

| Observations vector for chart | |

| Plotting statistic of chart | |

| Inverse variance covariance matric for the chart | |

| Control limit of the chart | |

| Estimator of | |

| Estimator of | |

| Multivariate normal distribution of | |

| shift | |

| Out-of-control mean vector | |

| Maximum value of | |

| Minimum value of |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Multivariate data structure.

Table A1.

Multivariate data structure.

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

Let be the data vectors of size n, which are independently sampled from a multivariate normal distribution at time with mean vector and variance–covariance matrix.

- For an in-control processNow,By substituting from (A1), becomesFor an in-control process and withAs and are vectors consisting of independent random sample values, therefore,, soNow,As and are independent sample means vector, therefore, soBy substituting from (A3), becomesAs the variance of a constant is zero, hence

- For an in-control processAs are the sample means vector of first sample, respectively, and all these means vector are independent of the next, that is, means vector. This indicates that, hence

- For in-control process

- For in-control processAs the estimators of and are and, hence (A6) and (A7) become the following, respectively:and

References

- Hotelling, H. Multivariate Quality Control-Illustrated by the Air Testing of Sample Bombsights; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, C.A.; Montgomery, D.C. A review of multivariate control charts. IIE Trans. 1995, 27, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Maravelakis, P.E. The Performance of the MEWMA Control Chart when Parameters are Estimated. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 1803–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosier, R.B. Multivariate Generalizations of Cumulative Sum Quality-Control Schemes. Technometrics 1988, 30, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatiello, J.J.; Runger, J.C. Comparisons of Multivariate CUSUM Charts. J. Qual. Technol. 1990, 22, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Fernandez, E. Multivariate Statistical Quality Control Using R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-5452-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, N.D.; Young, J.C.; Mason, R.L. Multivariate Control Charts for Individual Observations. J. Qual. Technol. 1992, 24, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, W.H.; Ncube, M.M. Multivariate CUSUM Quality-Control Procedures. Technometrics 1985, 27, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.S. Continuous Inspection Schemes. Biometrika 1954, 41, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, C.A.; Woodall, W.H.; Champ, C.W.; Rigdon, S.E. A Multivariate Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Control Chart. Technometrics 1992, 34, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.W. Control Chart Tests Based on Geometric Moving Averages. Technometrics 1959, 1, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Zahran, A.R. A Multivariate Adaptive Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Control Chart. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2010, 39, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, M.; Smith, I.; Assareh, H.; Mengersen, K. Implementation of multivariate control charts in a clinical setting. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2010, 22, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, K.; Tsung, F. A Variable-Selection-Based Multivariate EWMA Chart for Process Monitoring and Diagnosis. J. Qual. Technol. 2012, 44, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H. Variable Sampling Rate Multivariate Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Control Chart with Double Warning Lines. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2013, 10, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Tsung, F.; Zou, C. A new multivariate EWMA scheme for monitoring covariance matrices. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 2834–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jun, C.-H. A new multivariate EWMA control chart via multiple testing. J. Process Control 2015, 26, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsung, F.; Wang, K. Adaptive Charting Techniques: Literature Review and Extensions BT—Frontiers in Statistical Quality Control 9; Lenz, H.-J., Wilrich, P.-T., Schmid, W., Eds.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 19–35. ISBN 978-3-7908-2380-6. [Google Scholar]

- Psarakis, S. Adaptive Control Charts: Recent Developments and Extensions. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2015, 31, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Yu, J.; Kim, S.B. Adaptive nonparametric control chart for time-varying and multimodal processes. J. Process Control 2016, 37, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; AL-Marshadi, H.A.; Khan, N. A New X-Bar Control Chart for Using Neutrosophic Exponentially Weighted Moving Average. Mathematics 2019, 7, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajadi, J.O.; Riaz, M. Mixed multivariate EWMA-CUSUM control charts for an improved process monitoring. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2017, 46, 6980–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, N.A.; Abbasi, S.A.; Smith, A.N.H.; Anderson, M.J.; Pawley, M.D.M. A Multivariate Homogeneously Weighted Moving Average Control Chart. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 9586–9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N. Homogeneously weighted moving average control chart with an application in substrate manufacturing process. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 120, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersimis, S.; Panaretos, J.; Psarakis, S. Multivariate Statistical Process Control Charts and the Problem of Interpretation: A Short Overview and Some Applications in Industry. In Proceedings of the 7th Hellenic European Conference on Computer Mathematics and Its Applications, Athens, Greece, 22–24 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.W. An Introduction to Multivariate Statistical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-471-36091-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Jiao, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. An enhanced adaptive CUSUM control chart. IIE Trans. 2009, 41, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Does, R.J.M.M. An Alternative to the Bivariate Control Chart for Process Dispersion. Qual. Eng. 2008, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.A.; Miller, A. MDEWMA chart: An efficient and robust alternative to monitor process dispersion. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2013, 83, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Nazir, H.Z.; Riaz, M.; Lin, Z. An Efficient Nonparametric EWMA Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Chart for Monitoring Location. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2017, 33, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Riaz, M.; Abbasi, S.A.; Lin, Z. On efficient median control charting. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2014, 37, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Riaz, M.; Omar, H.M.; Xie, M. Alternative methods for the simultaneous monitoring of simple linear profile parameters. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 97, 2851–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridy, S.; Maged, A.; Kaytbay, S.; Araby, S. Effect of sample size on the performance of Shewhart control charts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 90, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.R.; Stoumbos, Z.G. Control Charts and the Efficient Allocation of Sampling Resources. Technometrics 2004, 46, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Wen, D.; Wu, Z.; Khoo, M.B. A comparison study on effectiveness and robustness of control charts for monitoring process mean and variance. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2012, 28, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tsung, F. A comparison study of effectiveness and robustness of control charts for monitoring process mean. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.P.; Casella, G. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-4419-1939-7. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, C.P.; Casella, G. Introducing Monte Carlo Methods with R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4419-1575-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mundform, D.J.; Schaffer, J.R.; Kim, M.-J.; Shaw, D.; Thongteeraparp, A.; Supawan, P. Number of Replications Required in Monte Carlo Simulation Studies: A Synthesis of Four Studies. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2011, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Maillardet, R.; Robinson, A. Introduction to Scientific Programming and Simulation Using R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781466569997. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-J. Number of Replications Required in Control Chart Monte Carlo Simulation Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, J.R.; Kim, M.-J. Number of Replications Required in Control Chart Monte Carlo Simulation Studies. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2007, 36, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, Q.-U.-A.; Riaz, M.; Ahmad, S. On designing a new Tukey-EWMA control chart for process monitoring. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 82, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Mahmood, T.; Abbasi, S.A.; Abbas, N.; Ahmad, S. Linear profile monitoring using EWMA structure under ranked set schemes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 91, 2751–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, W.; Kallenberg, W.C.M. Estimation in Shewhart control charts: Effects and corrections. Metrika 2004, 59, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Mehmood, R.; Ahmad, S.; Abbasi, S.A. On the Performance of Auxiliary-based Control Charting under Normality and Nonnormality with Estimation Effects. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2013, 29, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Naya, S.; Fernández-Casal, R.; Zaragoza, S.; Raña, P.; Tarrío-Saavedra, J. Constructing a Control Chart Using Functional Data. Mathematics 2020, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).