1. Introduction

Engineering is an imperfect science. Noisy measurements from sensors in state estimation [

1,

2], a constantly changing environment in guidance [

3,

4,

5], and improperly actuated controls [

6] are all major sources of error. The more these sources of error are understood, the better the final product will be. Ideally, every variable with some sort of uncertainty associated with it would be completely and analytically described with its probability density function (pdf). Unfortunately, even if this is feasible for the initialization of a random variable, its evolution through time rarely yields a pdf with an analytic form. If the pdf cannot be given in analytic form, then approximations and assumptions must be made.

In many cases, a random variable is quantified using only its first two moments—as with the unscented transform [

7]—and a further assumption is that the distribution is Gaussian. In cases where the variable’s uncertainty is relatively small and the dynamics governing its evolution are not highly nonlinear, this is not necessarily a poor assumption. In these cases, the higher order moments are highly dependent on the first two moments; i.e., there is a minimal amount of unique information in the higher order moments. In contrast, if either the uncertainty is large or the dynamics become highly nonlinear, the higher order moments become less dependent on the first two moments and contain larger amounts of unique information. In this case, the error associated with using only the first two moments becomes significant [

8,

9].

One method of quantifying uncertainty that does not require an assumption of the random variable’s pdf is polynomial chaos expansion (PCE) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. PCE characterizes a random variable as a coordinate in a polynomial vector space. Useful deterministic information about the random variable lies in this coordinate, including the moments of the random variable [

15]. The expression of the coordinate depends on the basis in which it is expressed. In the case of PCE, the bases are made up of polynomials that are chosen based on the assumed density of the random variable; however, any random variable can be represented using any basis [

16]. It is strongly noted that assuming the density of the random variable simply eases computation; with enough computing power, any random variable can be quantified with any basis [

17]. The most common basis polynomials are those that are orthogonal with respect to common pdfs, such as the Hermite-Gaussian and Jacobi-beta polynomial-pdf pairs.

Polynomial chaos has been used to quantify and propagate the uncertainty in nonlinear systems including fluid dynamics [

18,

19,

20,

21], orbital mechanics in multiple element spaces [

22], and has been expanded to facilitate Gaussian mixture models [

23]. While polynomial chaos has been well-studied for variables that exist in the

n-dimensional space of real numbers (

), many variables do not lie in this field. The variables that are of concern in this paper are angular variables. When estimating an angular random variable, such as the true anomaly of a body in orbit or vehicle attitude, a common approach is to assume that the variable is approximately equal to its projection on

and use methods designed for variables on that space. When the uncertainty is very small, this approximation is relatively effective; however, as the uncertainty increases, this approximation becomes invalid. Recently, work on directional statistics has been incorporated into state estimation, providing a method for estimating angular random variables directly on the

n-dimensional special orthogonal group (

) [

24,

25,

26]. Recent work [

27] has shown that polynomial chaos can be used to estimate the mean and variance of one-dimensional angular random variables and the set of equinoctial orbital elements elements [

28]. In neither case was a correlation estimated that included an angular state.

The sections of this paper include a detailed discussion of orthogonal polynomials in

Section 2, including those that are orthogonal on the unit circle and two of the more common circular pdfs. In

Section 3 an overview of polynomial chaos is given as well as the extension that has been made to include angular random variables, including the correlation between two angles. Finally, in

Section 4, numerical results are presented comparing the correlation between two angular random variables calculated using Monte Carlo and PCE.

2. Orthogonal Polynomials

Let

be an

n-dimensional vector space. A basis of this vector space is the minimal set of vectors that spans the vector space. An orthogonal basis is a subset of bases consisting of exactly

n basis vectors such that the inner product between any two basis vectors,

and

, is proportional to the Kronecker delta (

). Given mathematically with angle brackets, this orthogonal inner product takes the following form:

where

m and

n are part of the set of positive integers, including zero. In the event

, the set is termed orthonormal. The

standard basis vector of

is generally the

vector of the

n-dimensional identity; however, there are infinitely many bases for each vector space. It should be noted that it is not a requirement that a basis be orthogonal, merely linearly independent; however, the use of non-orthogonal bases is practically unheard-of.

An element

can be expressed in terms of an ordered basis

, as the linear combination

where

is the coordinate of

. While any set of independent vectors can be used as a basis, different bases can prove beneficial—possibly by making the system more intuitive or more mathematically straightforward. When expressing the state of a physical system, the selection of a coordinate frame is effectively choosing a basis for the inhabited vector space. Consider a satellite in orbit. If the satellite’s ground track is of high importance (such as weather or telecommunications satellites), an Earth-fixed frame would be ideal. However, in cases where a satellite’s actions are dictated by other space-based objects (such as proximity operations), a body-fixed frame would be ideal.

It is common to constrict the term vector space to the spaces that are easiest to visualize, most notably a Cartesian space, where the bases are vectors radiating from the origin at right angles. The term vector space is much more broad than this though. A vector space need only contain the zero element and be closed under both scalar addition and multiplication, which applies to much more than vectors.

Most notable in this work is the idea of a polynomial vector space. Let

be an

-dimensional vector space made up of all polynomials of positive degree

n or less with standard basis

. The inner product with respect to the function

on the real-valued polynomial space is given by

where

is a non-decreasing function with support

and

f and

g are any two polynomials of degree

n or less. A polynomial family

is a set of polynomials with monotonically increasing order that are orthogonal. The orthogonality condition is given mathematically as

where

is the polynomial of order

k,

c is a constant, and

is the support of the non-decreasing function

. Note that while polynomials of negative orders (

), referred to as Laurent polynomials, exist, they are not covered in this work.

The most commonly used polynomial families are categorized in the Askey scheme, which groups the polynomials based on the generalized hypergeometric function (

) from which they are generated [

29,

30,

31].

Table 1 lists some of the polynomial families, their support, the non-decreasing function they are orthogonal with respect to (commonly referred to as a weight function), and the hypergeometric function they can be written in terms of. For completeness,

Table 1 lists both continuous and discrete polynomial groups; however, the remainder of this work only considers continuous polynomials.

2.1. Polynomials Orthogonal on the Unit Circle

While the Askey polynomials are useful in many applications, their standard forms place them in the polynomial ring , or all polynomials with real-valued coefficients that are closed under polynomial addition and multiplication. These polynomials are orthogonal with respect to measures on the real line. In the event that a set of polynomials orthogonal with respect a measure on a curved interval (e.g., the unit circle) is desired, the Askey polynomials would be insufficient.

In [

32], Szegő uses the connection between points on the unit circle and points on a finite real interval to develop polynomials that are orthogonal on the unit circle. Polynomials of this type are now known as Szegő polynomials. Since the unit circle is defined to have unit radius, every point can be described on a real interval of length

and mapped to the complex variable

, where

i is the imaginary unit. All use of the variable

in the following corresponds to this definition. The orthogonality expression for the Szegő polynomials,

, is

where

is the complex conjugate of

and

is the monotonically increasing weight function over the support. Note that, as opposed to Equation (

2a), the Kronecker delta is not scaled, implying all polynomials using Szegő’s formulation are orthonormal.

While the general formulation outlined by Szegő is cumbersome—requiring the calculation of Fourier coefficients corresponding to the weight function and large matrix determinants—it does provide a framework for developing a set of polynomials orthogonal with respect to any conceivable continuous weight function. In addition to the initial research done by Szegő, further studies have investigated polynomials orthogonal on the unit circle [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Fortunately, there exist some polynomial families that are given explicitly, such as the Rogers-Szegő polynomials. The Rogers-Szegő polynomials have been well-studied [

39,

40,

41] and were developed by Szegő based on work done by Rogers over the

q-Hermite polynomials. For a more detailed description of the relationship between the Askey scheme of polynomials and their

q-analog, the reader is encouraged to reference [

31,

42].

The generating function for the Rogers-Szegő polynomials is given as

where

is the

q-binomial

The weight function that satisfies the orthogonality condition of these polynomials is

In addition to the generating function, a three-step recurrence [

43] exists, which is given by

For convenience, the first five polynomials are:

As is apparent, the q-binomial term causes the coefficients to be symmetric, which eases computation, and additionally, the polynomials are naturally monic.

2.2. Distributions on the Unit Circle

With the formulation of polynomials orthogonal on the unit circle, the weight function

has been continuously mentioned but not specifically addressed. In the general case, the weight function can be any non-decreasing function; however, the most common polynomial families are those that are orthogonal with respect to well-known pdfs, such as the ones listed in

Table 1. Because weight functions must exist over the same support as the corresponding polynomials, pdfs over the unit circle are required for polynomial orthogonal on the unit circle.

2.2.1. Von Mises Distribution

One of the most common distributions used in directional statistics is the von Mises/von Mises-Fisher distribution [

44,

45,

46]. The von Mises distribution lies on

(the subspace of

containing all points that are unit distance from the origin), whereas the von Mises-Fisher distribution has extensions into higher dimensional spheres. The circular von Mises pdf is given as [

24]

where

is the mean angular direction on a

interval (usually

),

is a concentration parameter (similar to the inverse of the standard deviation), and

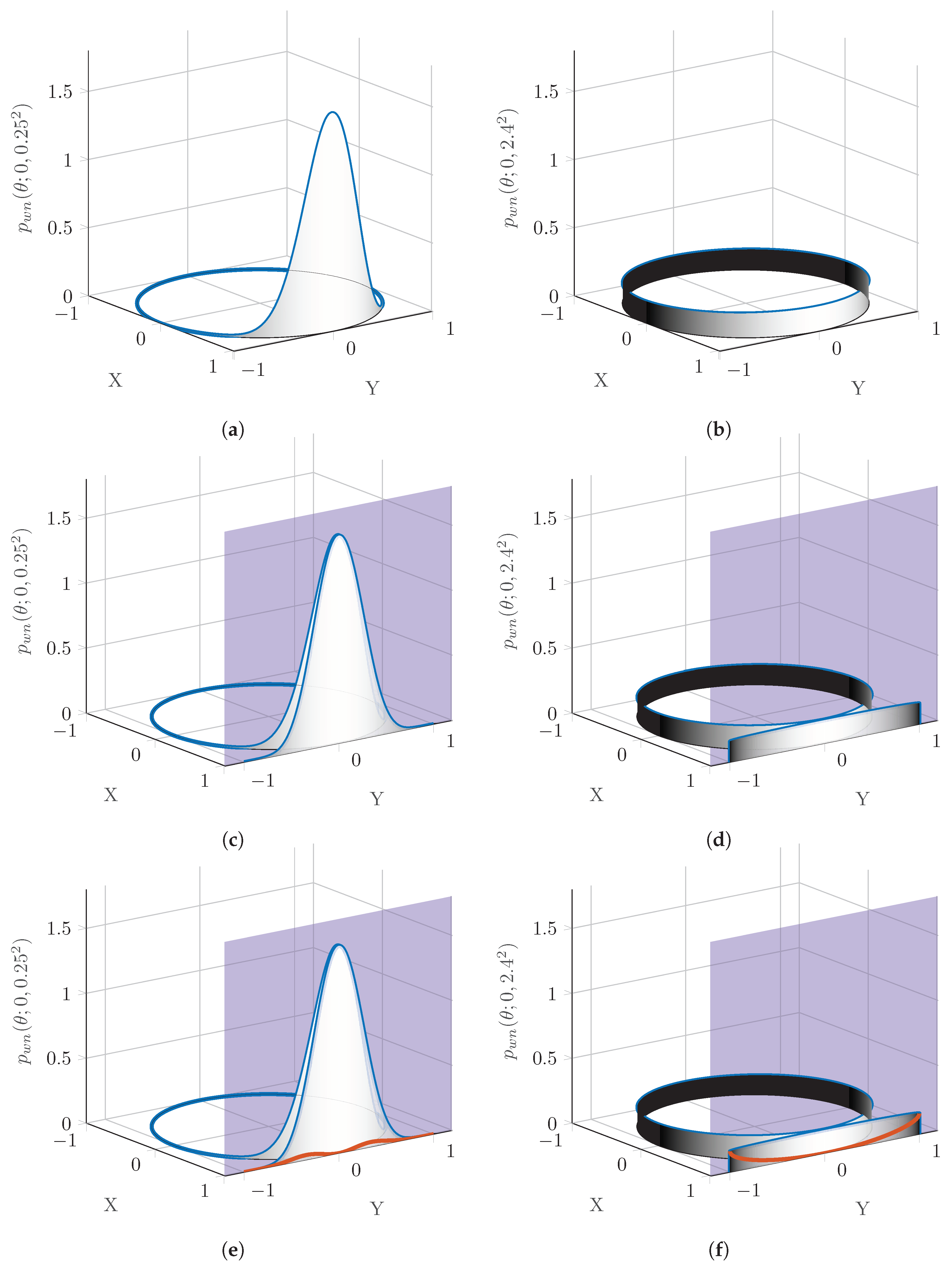

is the zeroth order modified Bessel function of the first kind. The reason this distribution is so common is its close similarity to the normal distribution. This can be seen in

Figure 1a, where von Mises distributions of various concentration parameters are plotted.

2.2.2. Wrapped Distributions

The easiest to visualize circular distribution, or rather group of distributions, that is discussed is the set of wrapped distributions. The wrapped distributions take a distribution on the real line and wrap it onto the unit circle according to

where the support of

is an interval of

, and the domain of

is an interval on

with length

. For example, wrapping a normal distribution takes the pdf

where the domain of

x is

, and

and

are the mean and standard deviation, respectively, and wraps it, resulting in the wrapped pdf (in this case wrapped normal)

where the domain of

is an interval on

with length

. Zero-mean normal distributions with varying values of

are wrapped, with the results shown in

Figure 1b.

Recall the weight function of the Rogers-Szegő polynomials in Equation (

4). As the log function is monotonically increasing, the term

increases monotonically as

q decreases. Observing the extremes of

q: as

q approaches 1,

approaches 0, and as

q approaches 0,

approaches

∞. Letting

and

, this becomes a zero-mean wrapped normal distribution.

It is clear from

Figure 1 that both distributions described previously have strong similarities to the unwrapped normal distribution.

Figure 1 also shows the difference in the standard deviation parameter. Whereas the wrapped normal distribution directly uses the standard deviation of the unwrapped distribution, the von Mises distribution is with respect to concentration parameter that is inversely related to the dispersion of the random variable. This makes the wrapped normal distribution slightly more intuitive when comparing with an unwrapped normal distribution.

2.2.3. Directional Statistics

The estimation of stochastic variables generally relies on calculating the statistics of that variable. Most notable of these statistics are the mean and variance, the first two central moments. For pdfs (

) on the real line that are continuously integrable, the central moments are given as

where

is the support of

. Although less utilized in general, raw moments are commonly used in directional statistics and are given as

or

where the slight distinction is that the integration variable is within the variable

. In addition, mean direction and circular variance are not the first and second central moments [

24]. Instead, both are calculated from the first moment’s angle (

) and length (

):

where

is the

-norm. From Mardia [

24], the length can be used to calculate the circular variance

and circular standard deviation

according to

Effectively, as the length of the moment decreases, the concentration of the pdf about the mean direction decreases and the unwrapped standard deviation (USTD) increases. Note that while the subscript in Equations (7) and (8) is 1, there are corresponding mean directions and lengths associated with all moments; however, these are rarely used in applications.

3. Polynomial Chaos

At any given instance in time, the deviation of the estimate from the truth can be approximated as a Gaussian distribution centered at the mean of the estimate. The space of these mean-centered Gaussians is known as a Gaussian linear space [

11]; when that space is closed (i.e., the distributions have finite second moments), it falls into the Gaussian Hilbert space

. At this point, what is needed is a way to quantify

, as this gives the uncertainty between the estimate and the truth. This can be achieved by projecting

onto a complete set of orthogonal polynomials when those basis functions are evaluated at a random variable

. While the distribution at any point in time natively exists in

, its projection onto the set of orthogonal polynomials provides a way of quantifying it by means of the ordered coordinates, as in Equation (

1).

The homogeneous chaos [

10] specifies

to be normally distributed with zero mean and unit variance (i.e., unit Gaussian), and the orthogonal polynomials to be the Hermite polynomials due to their orthogonality with respect to the standard Gaussian pdf [

47]. Not only does this apply for Gaussian processes, but the Cameron-Martin theorem [

48] says that this applies for any process with a finite second moment. Although the solution does converge as the number of orthogonal polynomials increases, further development has shown that, for different stochastic processes, certain basis functions cause the solution to converge faster [

16], leading to the more general polynomial chaos (PC).

To begin applying this method mathematically for a general stochastic process, let a stochastic variable,

, be expressed as the linear combination over an infinite-dimensional vector space, i.e.,

where

is the deterministic component and

is an

-order orthogonal basis function evaluated at, and orthogonal with respect to, the weight function,

. The polynomial families listed in

Table 1 have been shown by Xiu [

16] to provide convenient types of chaos based on their weight functions.

In general, the elements of the coordinate (

) are called the polynomial chaos coefficients. These coefficients hold deterministic information about the distribution of the random variable; for instance, the first and second central moments of

can be calculated easily as

where

denotes expected value.

Now, let

be an

n-dimensional vector. Each of the

n elements in

are expanded separately; therefore, Equation (

9) is effectively identical in vector form

Because the central moments are independent, the mean and variance of each their calculations similarly do not change. In addition to mean and variance, the correlation between two random variables is commonly desired. With the chaos coefficients estimated for each random variable and the polynomial basis known, correlation terms such covariance can be estimated.

3.1. Covariance

Let the continuous variables

a and

b have chaos expansions

The covariance between

a and

b can be expressed in terms of two nested expected values

the external of which can be expressed as a double integral yielding

where

and

are the supports of

a and

b respectively. Substituting the expansions from Equation (

11) into Equation (

12) and acknowledging that the zeroth coefficient is the expected value gives

Note the change of variables between Equations (

13a) and (13b). This is possible because the random variable and the weight function (

and

in this case) are over the same support. Additionally, the notation of the support variable is changed to be consistent with the integration variable.

As long as the covariance is finite, the summation and the integrals can be interchanged [

49], giving a final generalized expression for the covariance to be

In general, no further simplifications can be made; however, if the variables

x and

z are expanded using the same set of basis polynomials, then integration reduces to

containing a single variable with respect to the base pdf. Taking advantage of the basis polynomial orthogonality yields the following simple expression:

Combined with the variance, the covariance matrix of the

system of

x and

z just discussed is given as

For an

n-dimensional state, let

be the

matrix for the

n, theoretically infinite, chaos coefficients. Written generally, the covariance matrix in terms of a chaos expansion is

In cases where orthonormal polynomials are used, the polynomial inner product disappears completely leaving only the summation of the estimated chaos coefficients

3.2. Coefficient Calculation

The two most common methods of solving Equation (

9) for the chaos coefficients are sampling-based and projection-based. The first, and most common, approach requires truncating the infinite summation in Equation (

9) to yield

where the truncation term

N, which depends on the dimension of the state

n and the highest order polynomial

p, is

Drawing

Q samples of

, where

, and evaluating

and

at these points effectively results in randomly sampling

directly. After initial sampling,

can be transformed in

x (commonly

x is taken to be time so this indicates propagating the variable forward in time) resulting in a system of

Q equations with

unknowns that describe the pdf of

after the transformation that is given by

This overdetermined system can be solved for using a least-squares approximation. The coefficients can then be used to calculate convenient statistical data about (e.g., central and raw moments).

While the sampling-based method is more practical to apply, the projection based method is not dependent on sampling the underlying distribution. Projecting the pdf of

onto the

basis yields

The inner product is with respect to the variable

; therefore, the coefficient

acts as a scalar. The inner product is linear in the first argument; therefore, the summation coefficients can be removed from the inner product without alteration, that is

In contrast, if the summation is an element of the second argument, the linearity condition still holds; however, the coefficients incur a complex conjugate. Recall the basis polynomials are generally chosen to be orthogonal, so the right-hand inner product of Equation (

19) reduces to the scaled Kronecker delta, resulting in

This leaves only the

term (with the constant

), and an equation that is easily solvable for

is

which almost always requires numeric approximation.

3.3. Implementation Procedure

For convenience, the procedure for estimating the mean and covariance of a random state is given in Algorithm 1. Let

be the state of a system with uncertainty defined by mean

and covariance

subject to a set of system dynamics over the time vector

T. The algorithm outlines the steps required to estimate the mean and covariance of the state after the amount of time specified by

T.

| Algorithm 1 Estimation of mean and covariance using a polynomial chaos expansion. |

- 1:

procedurePCE_EST() ▹ Estimation of and using PCE - 2:

for to T do - 3:

Draw samples of based on chaos type ▹ Either randomly or intelligently - 4:

▹ Sample based on - 5:

from propagating based on state dynamics - 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

end for - 10:

return - 11:

end procedure

|

3.4. Complex Polynomial Chaos

While polynomial chaos has been well-studied and applied to a various number of applications in

, alterations must be made for the restricted space

due to its circular nature. A linear approximation can be made with little error when a circular variable’s uncertainty is small; however, as the uncertainty increases, the linearization can impose significant error.

Figure 2 shows the effects of projecting two wrapped normal distributions with drastically different standard deviations onto a tangent plane. The two wrapped normal distributions are shown in

Figure 2a,b, with USTDs of

and

rad, respectively. Clearly, even relatively small USTDs result in approximately uniform wrapped pdfs.

One of the most basic projections is an orthogonal projection from an

n-dimensional space onto an

dimensional plane. In this case, the wrapped normal pdf is projected orthogonally onto the plane

, which lies tangent to the unit circle at the point (1,0), coinciding with the mean direction of both pdfs. The plane, and the projection of the pdf onto this plane are shown in

Figure 2c,d. Approximating the circular pdf as the projected planar pdf comes with an associated loss of information. At the tangent point, there is obviously no information loss; however, when the physical distance from the original point to the projected point is considered, the error associated with the projected point increases. As is the case with many projection methods concerning circular and spherical bodies, all none of the information from the far side of the body is available in the projection. The darkness of the shading in all of

Figure 2 comes from the distance of the projection where white is no distance, and black is a distance value of least one (implying the location is on the hemisphere directly opposite the mean direction).

To better indicate the error induced by this type of projection,

Figure 2e,f also include a measure that shows how far the pdf has been projected as a percentage of the overall probability at a given point. At the tangent point, there is no projection required, therefore the circular pdf has to be shifted

in the

x direction. As the pdf curves away from the tangent plane, the pdf has to be projected farther. The difference between

Figure 2e and

Figure 2f is that the probability approaches zero nearing

in

Figure 2e; therefore, the effect of the error due to projection is minimal. In cases where the information is closely concentrated about one point, tangent plane projections can be good assumptions. Contrarily, in

Figure 2f the pdf does not approach zero, and therefore the approximation begins to become invalid. Accordingly, the red error line approaches the actual pdf, indicating that the majority of the pdf has been significantly altered in the projection.

In addition to restricting the space to the unit circle, most calculations required when dealing with angles take place in the complex field. In truth, the bulk of expanding polynomial chaos to be suitable for angular random variables is generalizing it to complex vector spaces. Previous work by the authors [

27] has shown that a stochastic angular random variable can be expressed using a polynomial chaos expansion. Specifically, the chaos expansion is one that uses polynomials that are orthogonal with respect to probability measures on the complex unit circle as opposed to the real line.

3.5. Szegő-Chaos

For the complex angular case, the chaos expansion is transformed slightly, such that

where, once again,

. The complex conjugate is not required in Equation (

21), but it must be remembered that the expansion must be projected onto the

conjugate of the expansion basis in Equation (20b). While ultimately a matter of choice, it is more convenient to express the expansion in terms of the conjugate basis, rather than the original basis.

Unfortunately, while the first moment is calculated the same for real and complex valued polynomials, the real valued process does not extend to complex valued polynomials. This is because of the slightly different orthogonality condition between real and complex valued polynomials. While the inner product given in Equation (

2a) is not incorrect, it is only valid for real valued polynomials. The true inner product of two functions contains a complex conjugate, that is

The difference between and is that the complex conjugate has no effect on . Fortunately, the zeroth polynomial of the Szegő polynomials is unitary just like the Askey polynomials. The complex conjugate has no effect; therefore the zeroth polynomial has no imaginary component and is calculated the same for complex and purely real valued random variables.

The complex conjugate of a real valued function has no effect; therefore, the first moment takes the form;

In general, calculation of the second raw moment and the covariance cannot be simplified beyond

The simplification from Equation (

14) to Equation (

15) as a result of shared bases can similarly be applied to Equation (

24). This simplifies Equation (

24) to a double summation but only a singular inner product (i.e., integral), i.e.,

The familiar expressions for the second raw moment given in Equation (10b) and the covariance given in Equation (

16) are special cases for

rather than general expressions.

3.6. Rogers-Szegő-Chaos

The Rogers-Szegő polynomials and the wrapped normal distribution provide a convenient basis and random variable pairing for the linear combination in Equation (

21). The Rogers-Szegő polynomials in Equation (

3) can be rewritten according to [

39]

where

q is calculated based on the standard deviation of the unwrapped normal distribution:

. These polynomials satisfy the orthogonality condition

where

is the theta function

which is another form of the wrapped normal distribution. Note the distinction between the variables

and

.

For convenience, the inverse to the given theta function is

The inverse of the theta function is particularly useful if the cumulative distribution function (cdf) is required to draw random samples. The number of wrappings in Equation (26) significantly affects the results. For reference, the results presented in this work truncate the summation to .

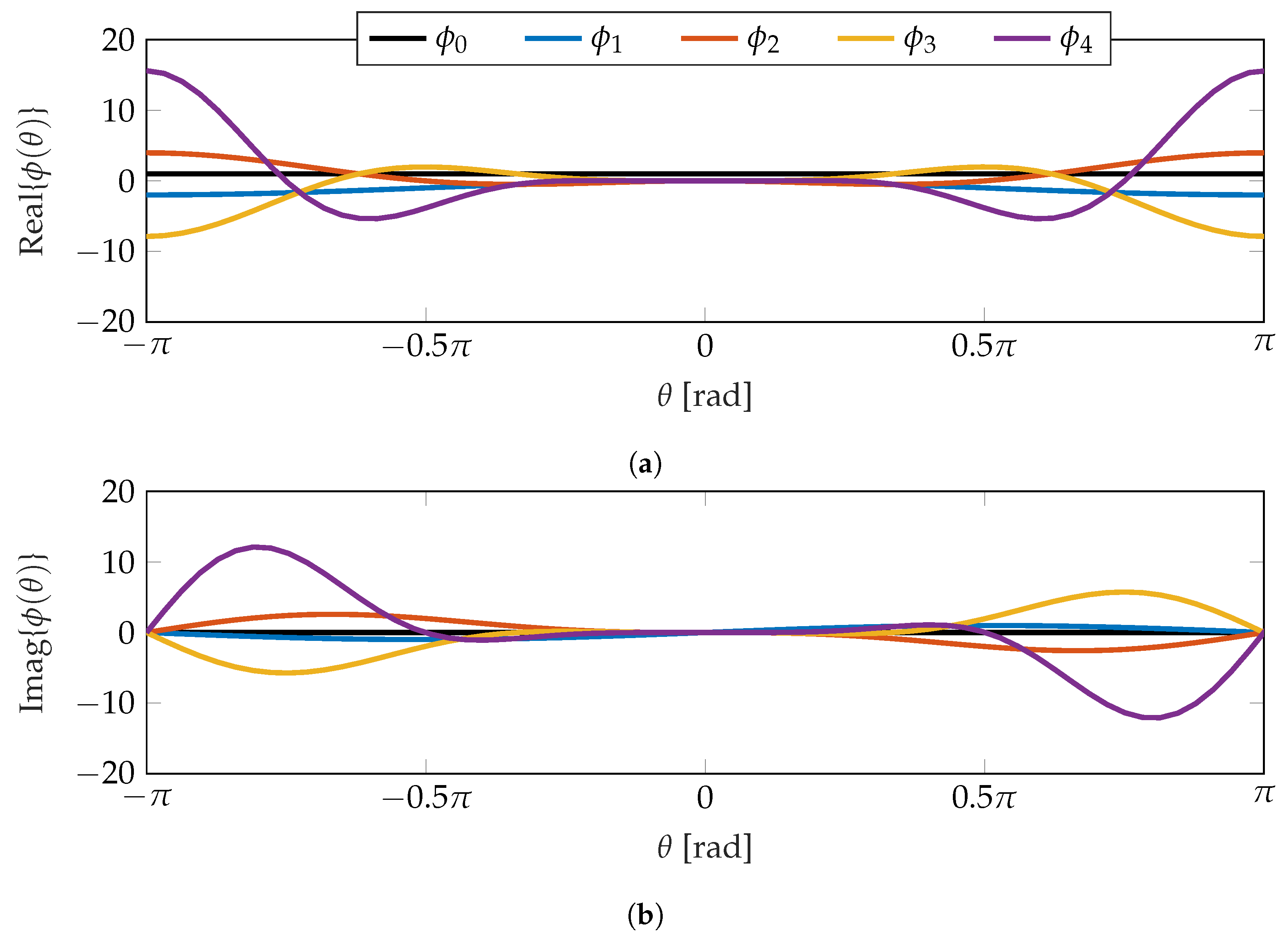

Written out, the first five orders of this form of the Rogers-Szegő polynomials are

and are shown graphically in

Figure 3. Because the polynomials are complex valued, the real and imaginary components are show, separately. In both cases, the polynomials are oscillatory, with the real component being symmetric about

, and the imaginary component being antisymmetric about

. Additionally, the amplitude of the oscillations increase both with increasing order and distance from

.

The zeroth polynomial is one, as is standard; therefore, the difference between the two generating functions given in Equations (25) and (26) will only be apparent in the calculation of moments beyond the first.

3.7. Function Complexity

As is to be expected, the computational complexity increases with increasing state dimension. It is therefore of interest to develop an expression that bounds the required number of function evaluations as a function of number of states and expansion order. Due to the many different methods of calculating inner products, all with different computational requirements, the number of functional inner products is what will be enumerated.

Let be a P-dimensional state vector consisting of angular variables, and let be the expansion order of each element in , where is the set of natural numbers, including zero. The number of inner products required to calculate the chaos coefficients in Equation (20b) for element is , where and is the element of .

Assume that the mean, variance, and covariance are desired for/between each element. The mean does not require any extra inner products, since the mean is simply the zeroth coefficient. The variance from Equation (

23) requires an additional

inner products for a raw moment, or

inner products for a central moment. Similarly, the covariance from Equation (

24) between the

and

elements requires

additional evaluations for a raw moment and

for a central moment. Combining these into one expression, the generalized number of inner product evaluations for raw moments with

is

and for central moments is

It should be noted that this is the absolute maximum number of evaluations that is required for an entirely angular state. In many cases inner products can be precomputed, the use of orthonormal polynomials reduces the coefficient calculation inner products by two, and expansions using real valued polynomials do not require these inner product calculations at all.

4. Numerical Verification and Discussion

To test the estimation methods outlined in

Section 3.5, a system with two angular degrees of freedom is considered. The correlated, nonlinear dynamics governing this body, the initial mean directions

/

, initial USTDs, and constant angular velocities

/

are given in

Table 2.

For every simulation, the run time is 4 s with

being

s; this equates to 81 time steps in each simulation. In

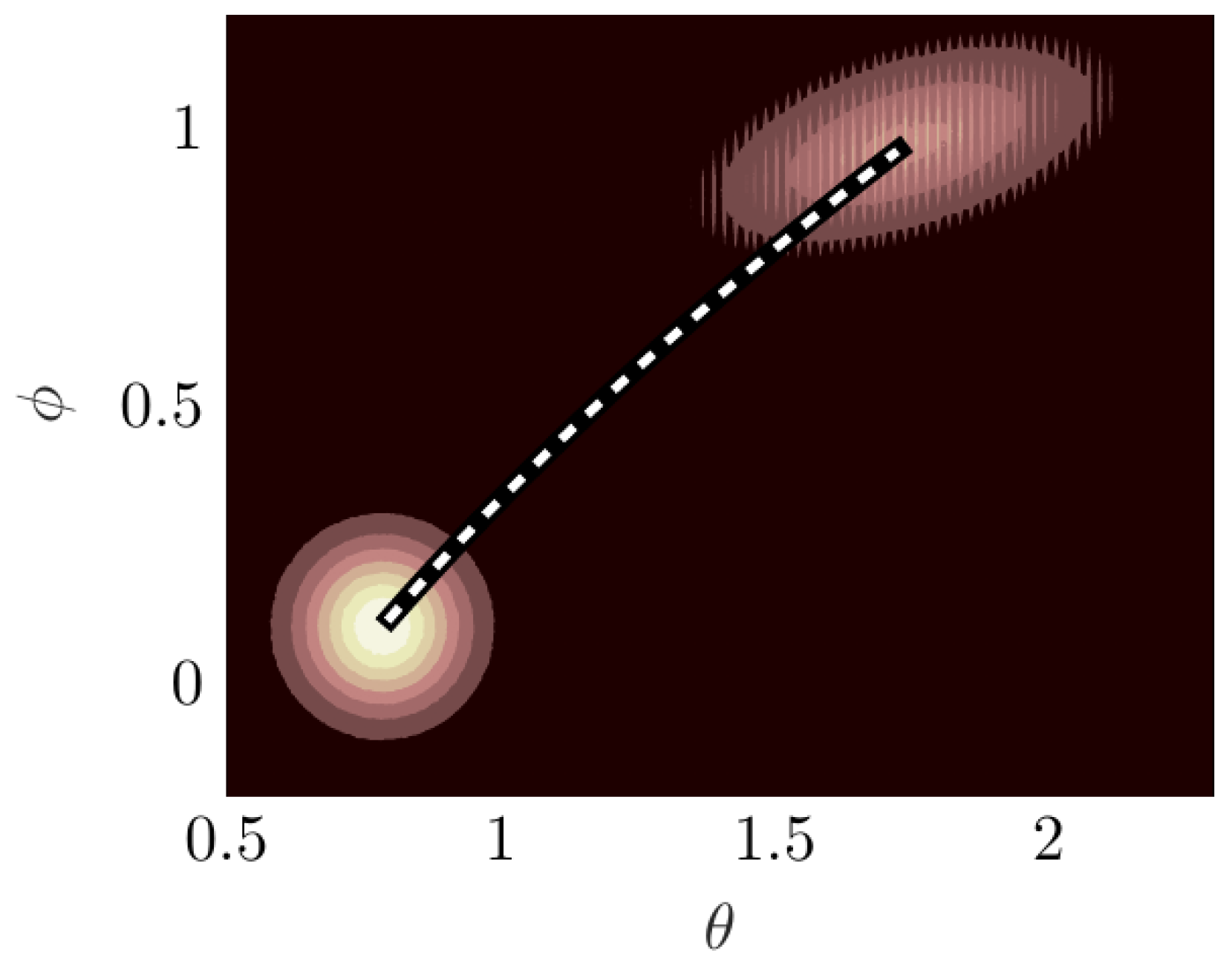

Figure 4, the joint pdf propagates from the initial conditions (bottom left) to the final state (top right). The initial joint pdf clearly reflects an uncorrelated bivariate wrapped normal distribution. After being transformed by the dynamics, the final joint pdf exhibits not just translation and scaling, but also rotation: indicating a non-zero correlation between the two angles, which is desired.

For a practical application, the mean and standard deviation/variance of each dimension, as well as the covariance between dimensions is desired. When dealing with angles, the mean direction and the standard deviation can be obtained from the first moment, omitting the second moment. Therefore, only the first moment and the covariance will be discussed. Recall the equations for the first moment and covariance are in terms of chaos coefficients and are given generally in Equations (

22) and (

24). Because two angles are being estimated, the supports of the integrals in Equations (

22) and (

24) are set as

: but it should be noted that the support is not rigidly defined this way, the only requirement is that the support length be

.

Rather than exploit the computational efficiency of methods such as quadrature integral approximations on the unit circle [

50,

51,

52], the integrals are computed as Riemann sums. Therefore, it is necessary to determine an appropriate number of elements that provides an adequate numerical approximation, while remaining computationally feasible.

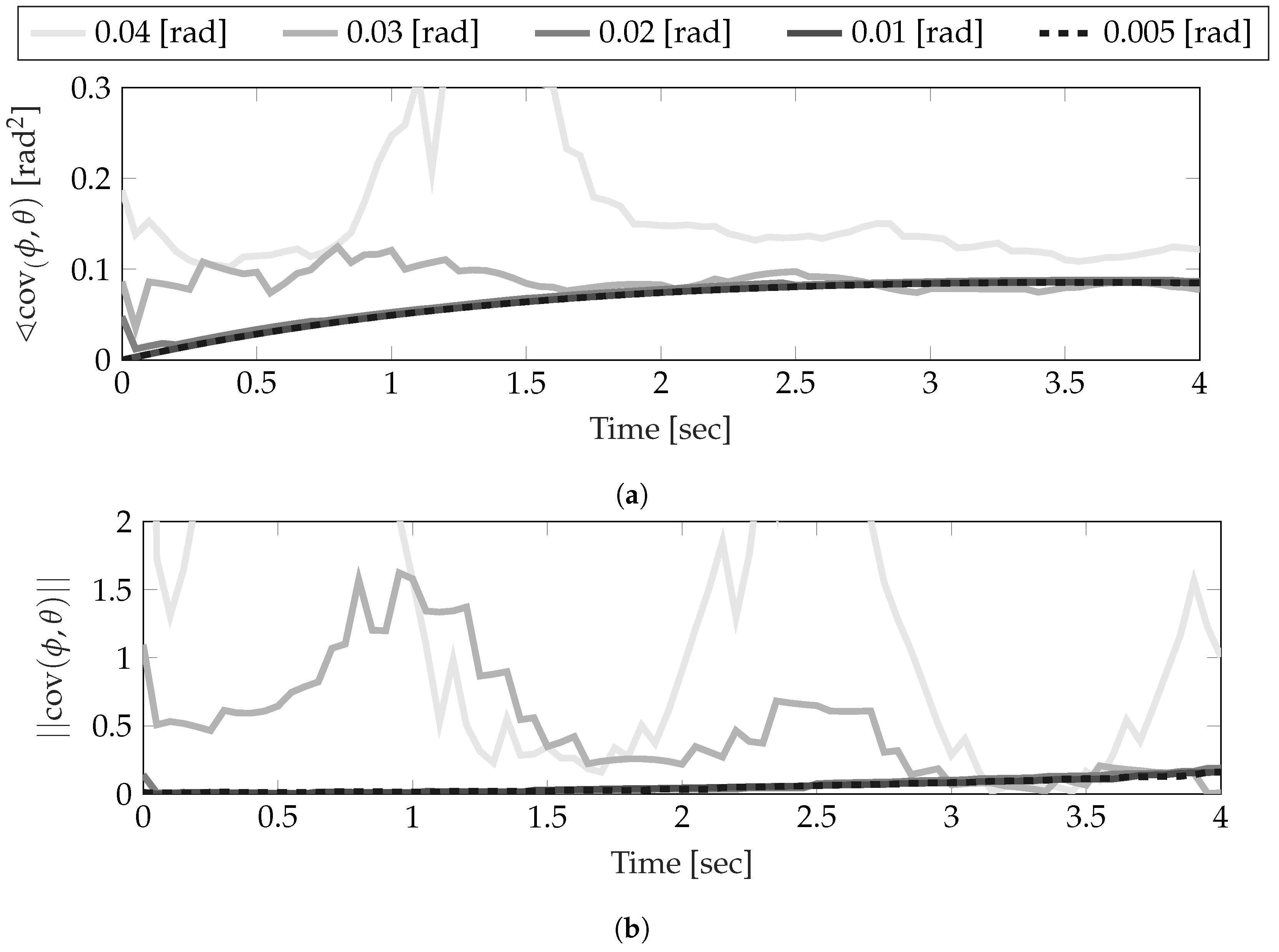

Figure 5 show the settling effect that decreasing the elemental angle has on the estimation of the covariance. Note that this figure is used to show the sensitivity of the simulation to the integration variable rather than the actual estimation of the covariance, which will be discussed later in this section. Both plots show the relative error of each estimate with respect to a Monte Carlo simulation of the joint system described in

Table 2. Clearly, as the number of elements increases, the estimates begin to converge until the difference between

rad (629 elements) and

rad (1257 elements) is perceivable only near the beginning of the simulation. Because of this, it can reasonably be assumed that any error in the polynomial chaos estimate with

is not attributed to numerical estimation of the integrals in Equations (

22) and (

24). Additionally, these results should also indicate the sensitivity of the estimate to the integration variable. Even though the dynamics used in this work’s examples result in a joint pdf that somewhat resembles wrapped normal pdfs, the number of elements used in the integration must still be quite large. The final numerical element that must be covered is the Monte Carlo. For these examples,

samples are used in each dimension.

In each of the examples in

Section 4.1, the polynomial chaos estimate first evaluates the Rogers-Szegő polynomials at each of the 1257 uniformly distributed angles (

), solves Equation (20b) for the chaos coefficients, and uses Equations (

22) and (

24) to estimate the mean and covariance. After this, the 1257 realizations of the state (

) are propagated forward in time according to the system dynamics. At each time step the system is expanded using polynomial chaos to estimate the statistics.

4.1. Simulation Results

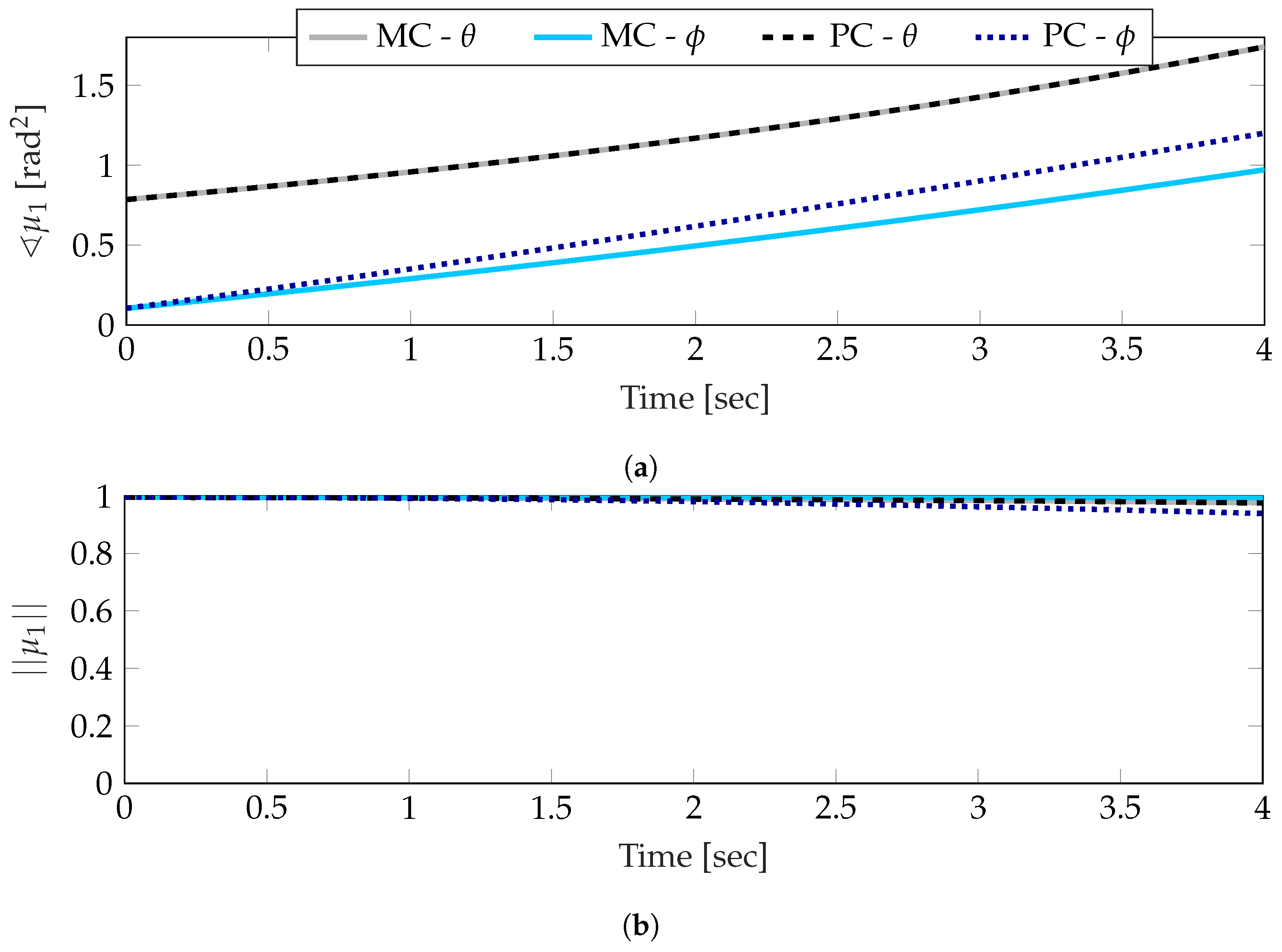

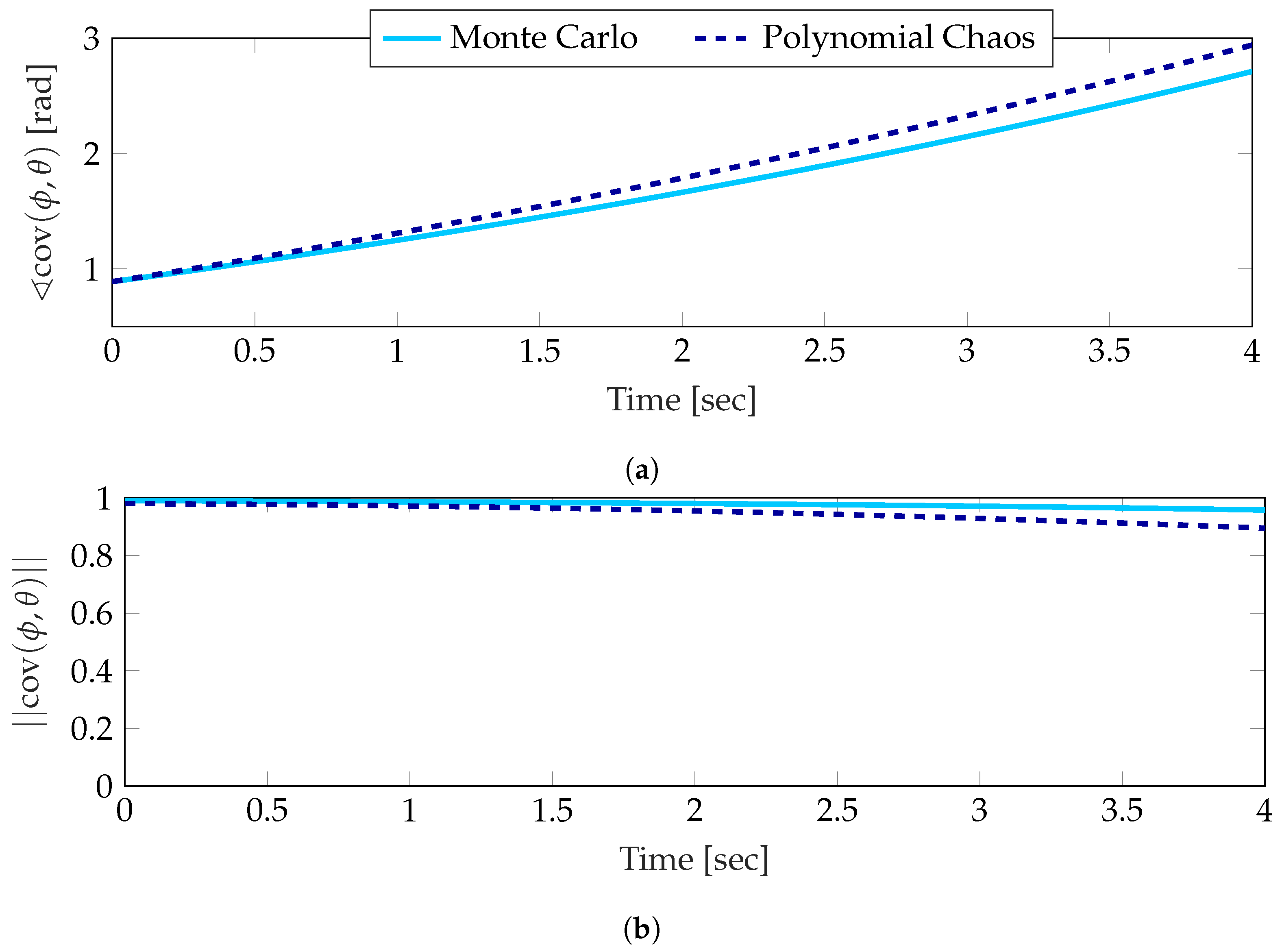

The estimations of the first moment and covariance of the system described by the simulation parameters in

Table 2 are shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. In both cases, the angle and length of the estimate are presented, rather than the exponential form used in the polynomial chaos expansion. This representation much more effectively expresses the mean and concentration components of the estimate, which are directly of interest when examining statistical moments.

Beginning with the mean estimate from a fifth order polynomial chaos expansion in

Figure 6, the mean direction of the angle

is nearly identical to the Monte Carlo estimate, while the estimate of

begins to drift slightly as the simulation progresses. Of the two angles, this makes the most since; recalling

Table 2, only the dynamics governing

are correlated with

, the dynamics governing

are only dependent on

. In comparison, the estimates of the lengths are both much closer to the Monte Carlo result. Looking closely at the end of the simulation, it can be seen that, again,

is practically identical, and there is some small drift in

downwards, indicating that the estimate reflects a smaller concentration. Effectively, the estimation of the mean reflects some inaccuracy; however, this inaccuracy is partly reflected in the larger dispersion of the pdf.

Similarly to the mean, a small drift can be seen in the estimate of the covariance in

Figure 7. In both cases the initial estimate is nearly identical to the Monte Carlo result; however, throughout the simulation a small amount of drift becomes noticeable. While this drift is undesirable, the general tracking of the polynomial chaos estimate to the Monte Carlo clearly shows that the correlation between two angles can be approximated using a polynomial chaos expansion.

4.1.1. Unwrapped Standard Deviation and Joint PDF Assumptions

From the discussion of the generating function for the Rogers-Szegő polynomials Equation (

25), it is clear that these polynomials are dependent on the USTD. Unfortunately this means that the polynomials are unique to any given problem, and while they can still be computed ahead of time and looked up, it is not as convenient as problems that use polynomials that are fixed (e.g., Hermite polynomials).

Additionally, the inner product in Equation (

23), which describes the calculation of the covariance, requires the knowledge of the joint pdf between the two random variables. In practice, there is no reasonable way of obtaining this pdf; and if there is, then the two variables are already so well know, that costly estimation methods are irrelevant.

It is therefore of interest to investigate what effects making assumptions about the USTD and the joint pdf have on the estimates. The basis polynomials are evaluated when solving for the chaos coefficients Equation (20b) and when estimating the statistical moments Equations (

22)–(

25) at every time step. If no assumption is made about the USTD, then the generating function in Equation (

25) or the three step recursion in Equation (

5) must be evaluated at every time step as well. In either case, the computational burden can be greatly reduced if the basis polynomials remain fixed, requiring only an initial evaluation. Additionally, if the same USTD is used for both variables, than the simplification from two to one integrals in Equation (

25) can be made.

While only used in the estimation of the covariance, a simplification of the joint pdf will also significantly reduce computation and increase the feasibility of the problem. The most drastic of simplifications is to use the initial, uncorrelated joint pdf. Note that the pdf used in the inner product is mean centered at zero (even for Askey chaos schemes); therefore, the validity of the estimation will not be effected by any movement of the mean.

Assuming the USTD to be fixed at

for both random variables and the joint pdf to be stationary throughout the simulation led to estimates that are within machine precision of the unsimplified results in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. This is to be expected when analyzing Askey-chaos schemes (like Hermite-chaos) that are problem invariant. In instances where the USTD of the wrapped normal distribution is low enough that probabilities at

are approximately zero, the wrapped normal distribution is effectively a segment of the unwrapped normal distribution, because the probabilities beyond

are approximately equal to zero. However, in problems where the USTD increases, the wrapped normal distribution quickly approaches a wrapped uniform distribution, this makes the time-invariant USTD a poor assumption. While a stationary USTD assumption may not hold as well for large variations in USTD, highly correlated, or poorly modeled, dynamical systems, it shows that some assumptions and simplifications can be made to ensure circular polynomial chaos is a practical method of estimation.

4.1.2. Chaos Coefficient Response

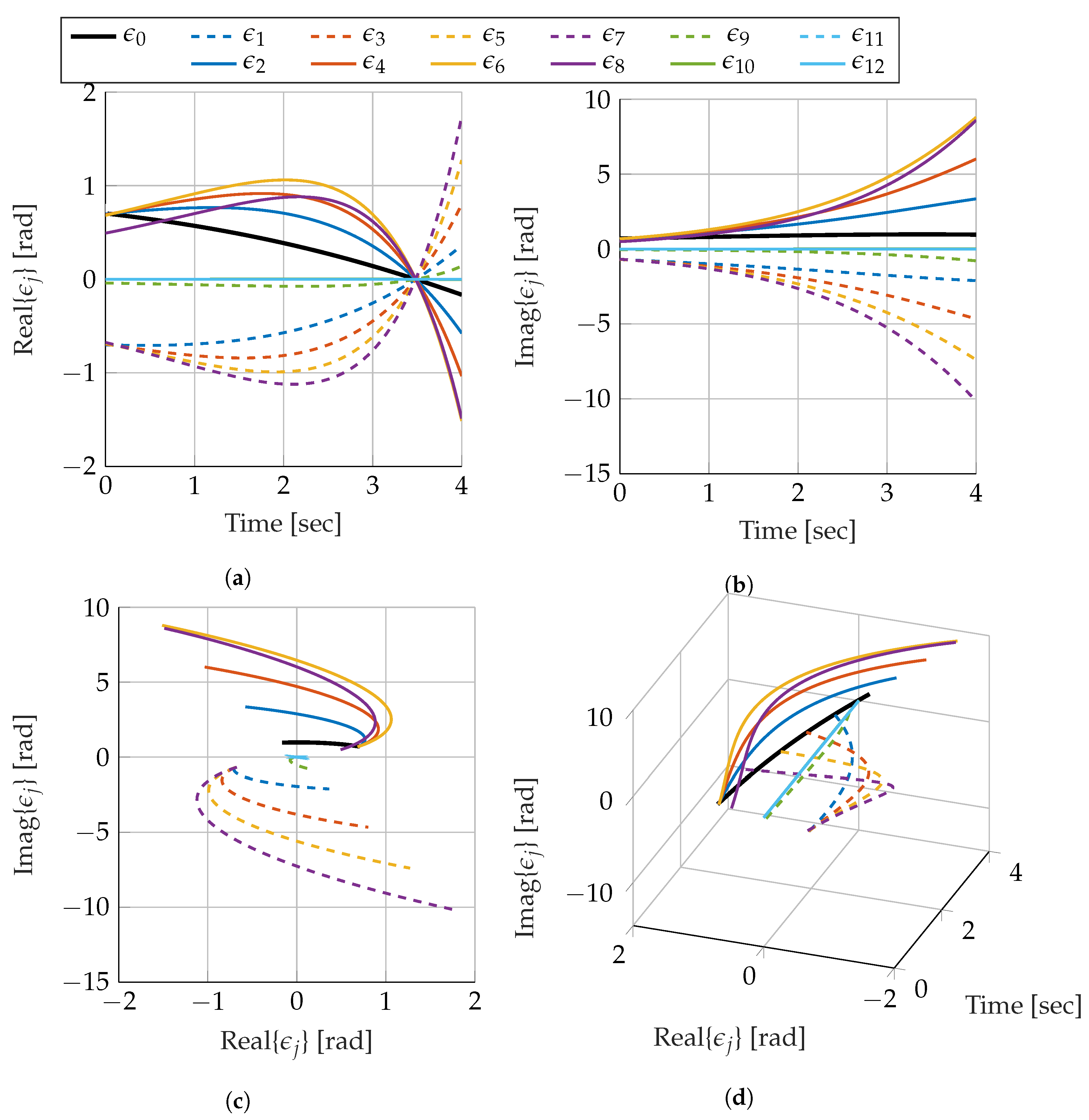

The individual chaos coefficients are not always inspected for problems using Askey-chaos simply due to the commonality of Askey-chaos. The adaptation of polynomial chaos to use the Szegő polynomials, and thus expanding from real to complex valued estimates presents a case that warrants inspection of the chaos coefficients.

Figure 8 show the time evolution of the first 13 chaos coefficients (including the zeroth coefficient) that describe the random variable

.

What becomes immediately apparent is that the coefficients are roughly anti-symmetrically paired until the length of the coefficient begins to approach zero. In this specific case, the eighth coefficient in

Figure 8 initiates this trend. This is the first coefficient that does not have an initial estimate coinciding with lower ordered coefficients. All coefficients following this one show very little response to the system. This is to be expected. Recall the calculation of the chaos coefficient includes the product of polynomial and pdf as well as a division by the self inner product of each polynomial order (i.e.,

). The polynomial and pdf product have opposing behaviors when approaching

from 0. Whereas the polynomial oscillation amplitude increases, the tails of the pdf approach probability values of zero. This ensures the growth in the higher order polynomials is mitigated.

For brevity, only the coefficients from the variable

are shown. These have a much more interesting response than

due to the nature of the dynamics. The most notable part of the coefficients from

is that none of the coefficients ever move beyond the complex unit circle, which from

Figure 8c, is clearly not the case for

. In fact, the coefficients describing

stay close to the complex unit circle and just move clockwise about it. Similarly, the eighth and higher coefficient lengths begin collapse to zero rad. For this problem (and presumably most problems) almost all of the information is coming from the first two coefficients. Comparing the estimates using two, three, and ten coefficients yields the same results to within machine precision. This is not surprising when considering the inner products (

Table 3) that are required to estimate the covariance; each of the inner products are effectively zero when compared with

and

. While having to only compute two significant chaos coefficients makes computation easier, it also limits the amount of information that is used in the estimate; however, for simple problems such as this one, two significant coefficients are satisfactory.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

One method of quantifying the uncertainty of a random variable is a polynomial chaos expansion. For variables that exist only on the real line, this type of expansion has been well studied. This work developed the alterations that must be made for a polynomial chaos expansion to be valid for random variables that exist on the unit circle, specifically the complex unit circle (where the y coordinate becomes imaginary).

Previous work has shown that polynomial chaos can be used with the Rogers-Szegő polynomials to estimate the raw moments of a random variable with a wrapped normal distribution. A generalized set of expressions for the mean and covariance of multi-dimensional systems for both real and complex systems has been presented that do not make the assumption that each variable has been expanded with the same set of basis polynomials. An example of two angular random variables—one with correlated dynamics, and one without—has been presented. The mean of each random variable as well as the covariance between them is estimated and compared with Monte Carlo estimates. In the case of the uncorrelated random variable, the mean estimates are highly accurate. For the correlated random variable, the estimate is found to slowly diverge from the Monte Carlo result. A similar small divergence is observed in the covariance estimate; however, the general trend is similar enough to indicate the error is not in the formulation of the complex polynomial chaos. Additionally, an approximation to the basis polynomials and time-varying joint probability density function (pdf) is made, without loss of accuracy in the estimate. From the estimates of the mean and covariance, it is clear that the Rogers-Szegő polynomials can be used as an effective basis for angular random variable estimation. However, for more complex problems, different polynomials should be considered, specifically polynomials with an appropriate number of non-negligible self inner products.