Abstract

In 1965, Statz et al. (J. Appl. Phys. 30, 1510 (1965)) investigated theoretically and experimentally the conditions under which spiking in the laser output can be completely suppressed by using a delayed optical feedback. In order to explore its effects, they formulate a delay differential equation model within the framework of laser rate equations. From their numerical simulations, they concluded that the feedback is effective in controlling the intensity laser pulses provided the delay is short enough. Ten years later, Krivoshchekov et al. (Sov. J. Quant. Electron. 5394 (1975)) reconsidered the Statz et al. delay differential equation and analyzed the limit of small delays. The stability conditions for arbitrary delays, however, were not determined. In this paper, we revisit Statz et al.’s delay differential equation model by using modern mathematical tools. We determine an asymptotic approximation of both the domains of stable steady states as well as a sub-domain of purely exponential transients.

1. Introduction

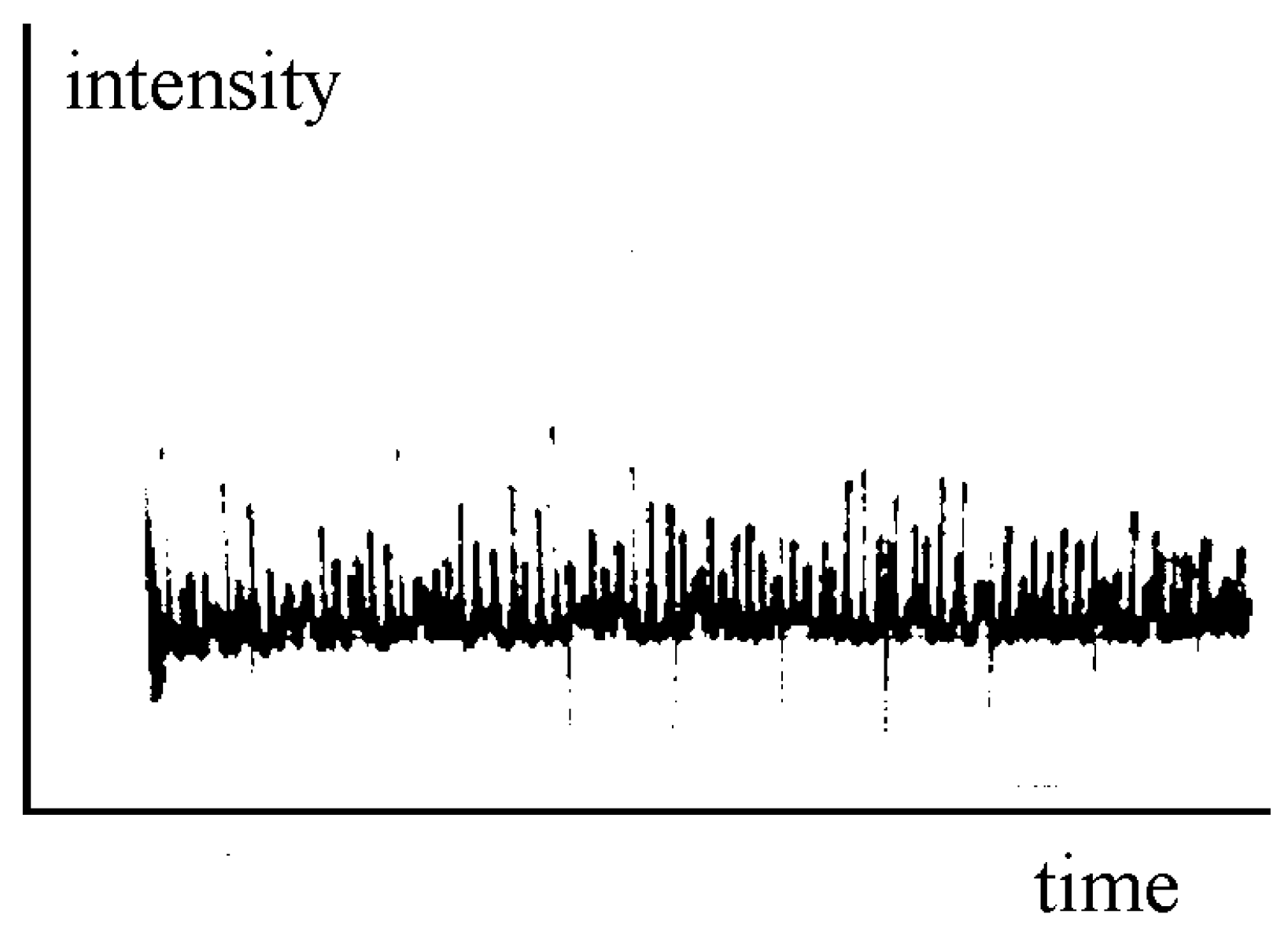

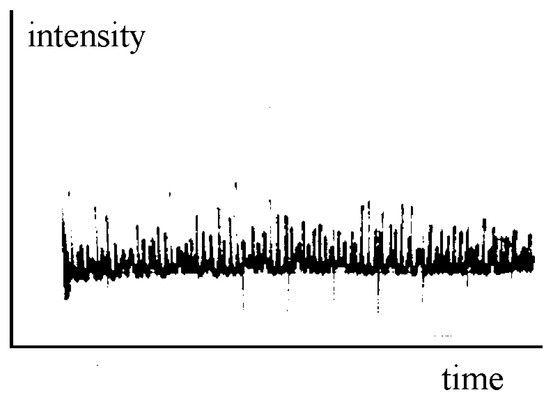

One of the unexpected features of early laser systems was the emergence of output pulsations. Even before the first laser has been built, researchers had undertaken studies of instabilities in masers (a maser is a device that produces coherent electromagnetic waves at microwave frequencies through amplification by stimulated emission. The laser works by the same principle as the maser but produces higher frequency coherent radiation at visible wavelengths) and pulsations were actually observed in ruby masers in 1958 [1,2]. The first working laser was a ruby laser made by Maiman in 1960 (the first laser was a solid-state laser: Ruby emitting at nm. Ruby consists of the naturally formed crystal of aluminum oxide (AlO)) [3]. The complex spiking behavior of ruby lasers [4] was not anticipated and attracted a great deal of theoretical interest (see Figure 1). Similar pulsations have been reported for solid-state, liquid, and gas laser systems.

Figure 1.

High-frequency pulsating oscillations in the maser output. Adapted with permission from Figure 2b of [5] © The Optical Society.

First derived by Statz and de Mars [6], two rate equations provide a fair description of the laser dynamical response. Computer simulations, however, predicted a train of regular and damped spikes at the output of the laser [7,8,9]. They are called “relaxation oscillations” (ROs). This discrepancy between theory and experiment has to do with the fact that the spiking behavior dies out very slowly. Mechanical and thermal shocks and disturbances present in many lasers, and especially the ruby laser, act to continually re-excite the spiking behavior [10].

It is desirable for some applications to have a smooth output with no or very small amplitude modulation. Non-spiking operation has been achieved in ruby lasers [11,12,13,14] by sampling a portion of the output beam with a photodiode and using the detector signal to control the voltage applied to an electro-optic shutter located inside the resonator. In order to obtain spike suppression, the delay time between the detector and the shutter must be much shorter than the spike width of approximately to 1 s [10].

In 1965, Statz et al. [8] investigated theoretically and experimentally the conditions under which spiking in the laser output can be completely suppressed using a delayed optical feedback. They consider the laser rate equations supplemented by a delayed feedback term. The equations in their original form, as well as their formulation in modern notations, are documented in Appendix A. The same stabilization problem due to a delayed feedback has been later considered by Krivoshchekov et al. [15]. Their rate equations are documented in Appendix B. The delay differential equation (DDE) of Statz et al. [8] has been explored numerically, while the DDE problem of Krivoshchekov et al. [15] has been analyzed for small delays and small feedback gains.

To the best of our knowledge, the publication by Statz et al. [8] is the first one in laser physics, where a DDE problem is clearly formulated. The effect of a delayed feedback on a laser is an important topic in laser physics. In particular, semiconductor lasers (SLs) used in our everyday applications are extremely sensitive to optical feedback. Dynamical instabilities were identified in the early 1970s [16,17] and have been studied since then with various motivations [18,19,20].

The plan of the paper is as follows. Section 2 introduces Statz et al. delay equations and analyzes the stability properties of the non-zero intensity steady state. Section 3 reviews the analysis in [15] based on the short delay limit. Lastly, we discuss the role of the damping rate on the stability conditions.

2. Rate Equations

The basic idea of Statz et al. [8] was to provide additional losses in the laser cavity through a negative delayed feedback. Their objective was to determine the feedback conditions for which damped oscillations are replaced by pure exponential decays. In the dimensionless form, the laser rate equations for the intensity output of the laser I and the population inversion D are given by (see Appendix A for details)

where is the pump parameter and is one control parameter. is the ratio of the intensity and population time scales. and denote the gain and the delay of the feedback, respectively. The values of the parameters used in [8] are documented in Appendix A. We note that is small. The limit is singular because multiplies the right hand side of Equation (2). We eliminate this singularity by a change of variables described in Appendix A. The new dependent variables x and y represent deviations of I and D with respect to their steady state values and [21] The new time takes into account the basic time scale of the laser damped ROs when the steady state is slightly perturbed. These equations are

The new parameters and are defined in Appendix A. The term multiplying in Equation (4) describes the slow damping of the free-running laser intensity oscillations. The delayed term in Equation (1) is a second source of dissipation if the delay is small. Assuming we neglect the term multiplying in (4). We obtain

The non-zero intensity steady state is From the linearized equations, we determine the characteristic equation for the growth rate It is given by

Introducing into Equation (7) and taking the real and imaginary parts provide two equations for u and We find

The case of a purely real corresponds to From Equation (8), we determine in implicit form as

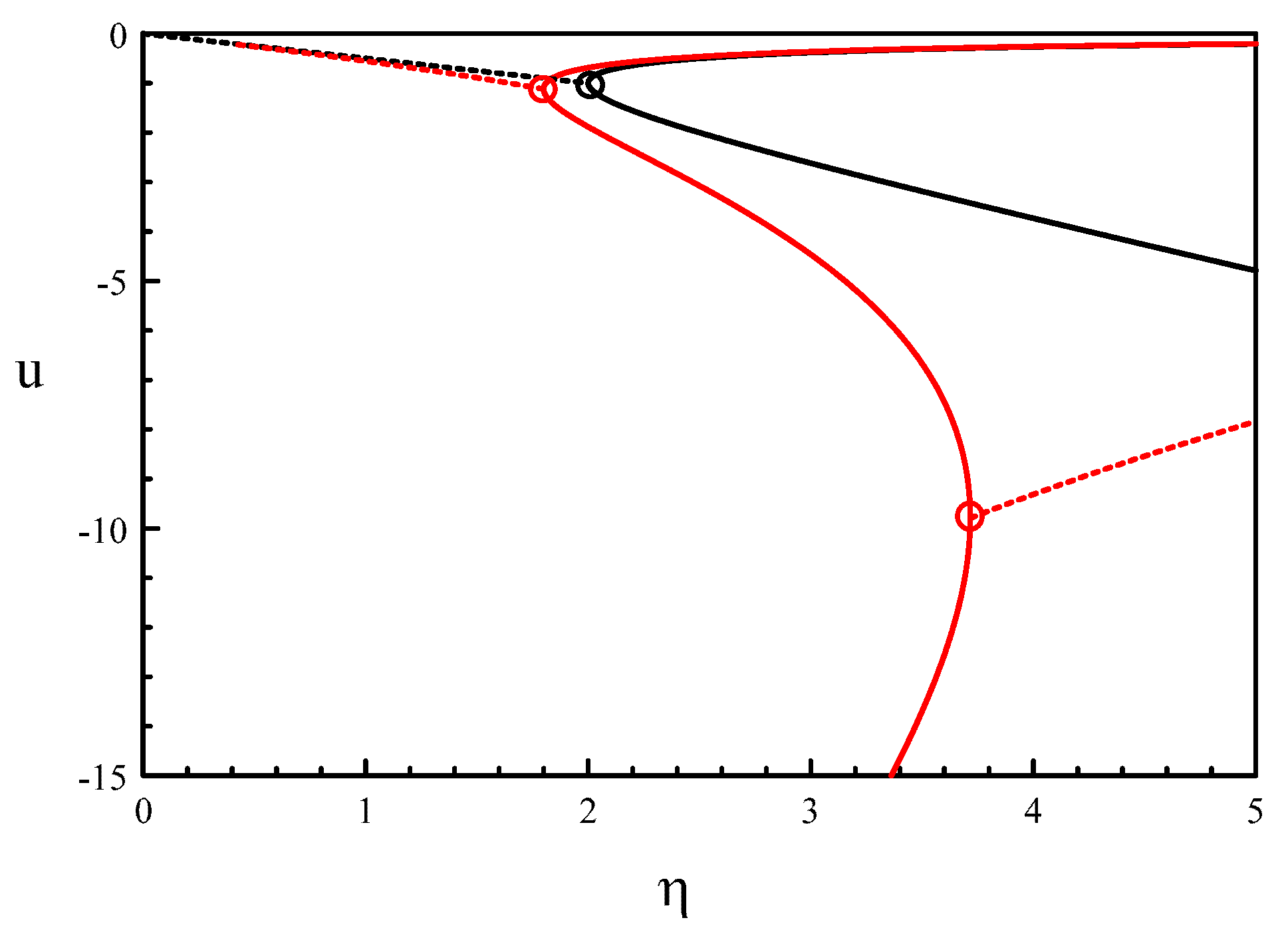

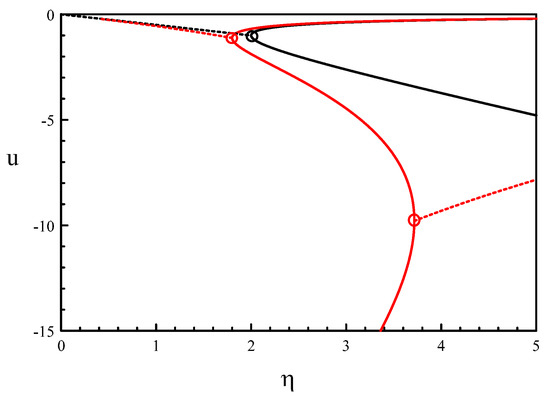

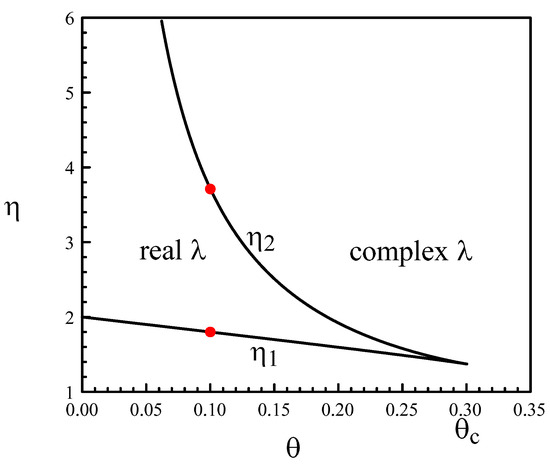

and since . The case of complex has been investigated by solving numerically Equations (8) and (9). Figure 2 represents the real part u as a function of The full lines correspond to real for (black) and (red). The broken lines correspond to complex for (black) and (red). The circles indicate limit points (LPs) where there is a transition between real and complex . If , the domain of pure exponential decays lies between the two red LPs. They are determined by using (10) and by applying the condition We find that in implicit form, is

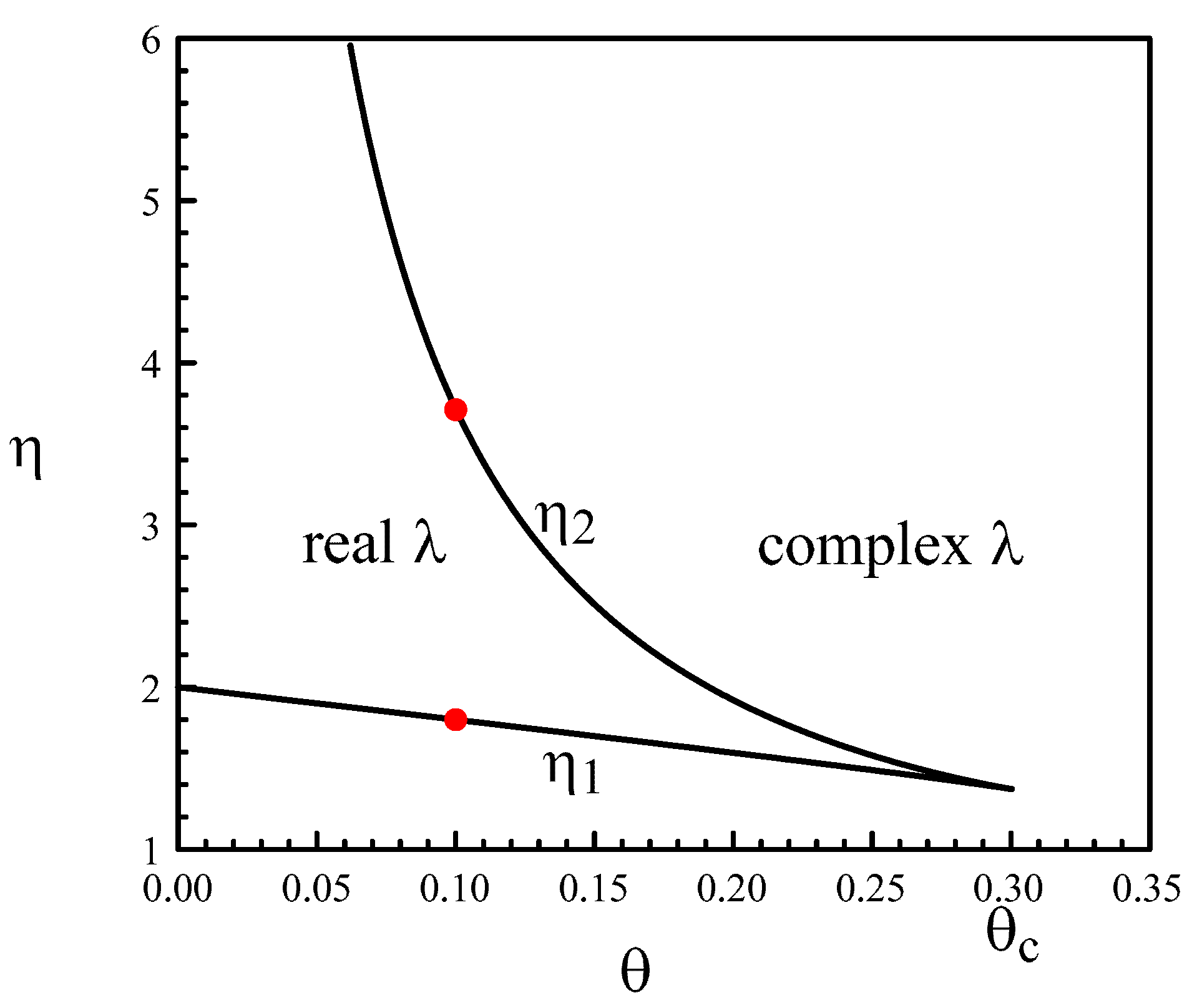

Together with (10), we have a parametric solution for and We proceed as follows. We progressively decrease u from a low negative value and determine from (11). We then use (10) with and determine The solution is shown in Figure 3. There is a critical point above which no real roots are possible. To find its value, we use (11) and determine from the condition We find We substitute this value into (11) and obtain

If we find from (10) and (11), the following approximations for the LPs

The first LP moves to the fixed value , while the second LP moves to infinity in the limit of small delays. The later case will be further analyzed in Section 3.

Figure 2.

Real part u as a function of the feedback rate for (black) and (red). The full and broken lines correspond to real roots and complex roots of the characteristic Equation (7), respectively. Transitions between real and complex roots occur at limit points (encircled).

A Hopf bifurcation instability is possible and corresponds to . From (8) and (9), we determine the conditions

They admit the solutions

where

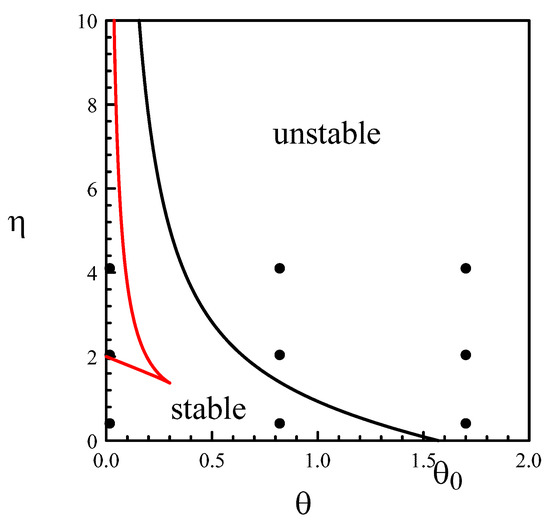

and n is detailed in (18) and (19). The dots in Figure 4 are the values considered by Statz et al. [8] in their numerical simulations (listed in Table A1). As we can see, five dots are in the domain of unstable steady states. The simulations in [8] were limited in integration time but clearly showed growing oscillations for those values (except for the middle point at .

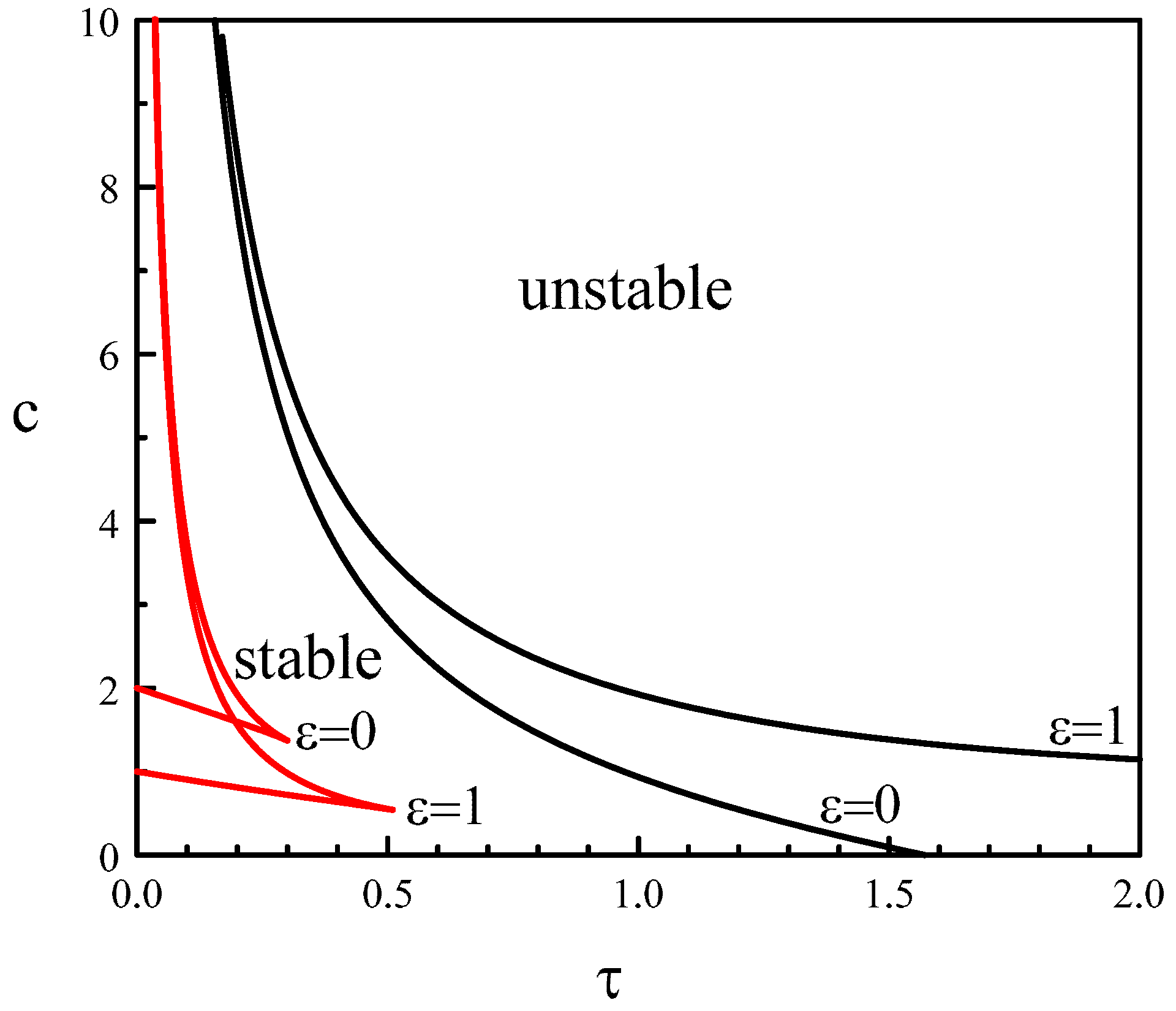

Figure 4.

First Hopf bifurcation line delimiting the domain of stable steady states (black). It is given by (18) with . It contains a smaller domain where the decay to the steady state is purely exponential (red). The dots are the values of the parameters used by Statz et al. [8] in their numerical simulations. They are documented in Table A1.

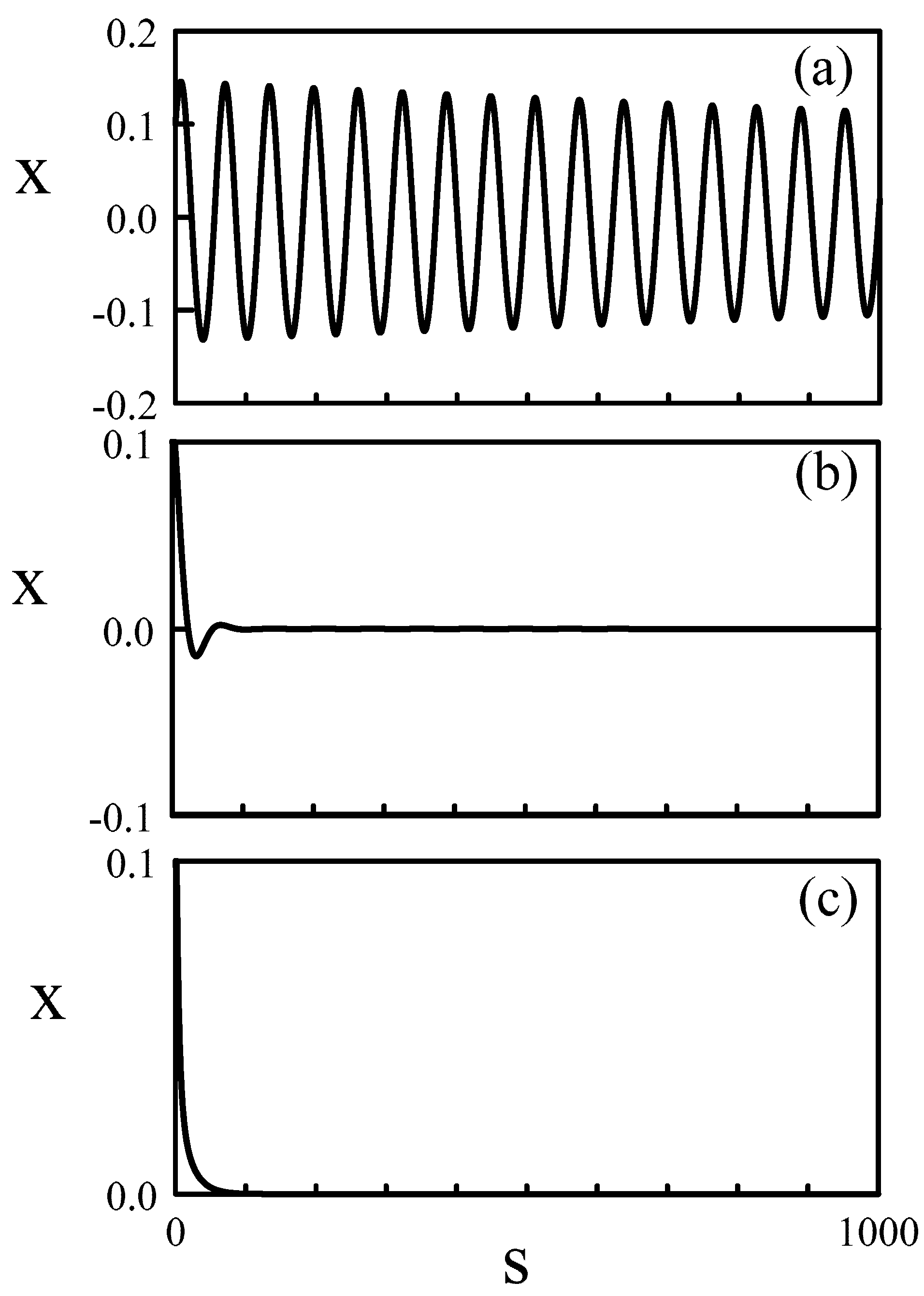

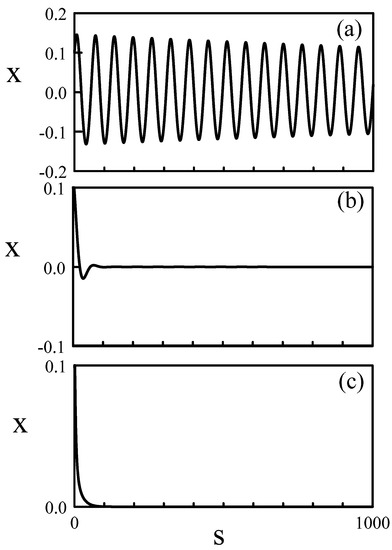

The predictions of the linear stability analysis are verified numerically by simulating Equations (3) and (4). Figure 5a corresponds to (no feedback) and exhibits the slowly damped ROs. Figure 5b is for , which is still part of the domain of decaying oscillations although they are quickly damped. Figure 5c is for , where the decay to the steady state is purely exponential. We note that already for oscillations are strongly damped. This can be explained by considering Equations (3) and (4), and by analyzing the linear stability of The characteristic equation for the growth rate is

If , the damping rate of the RO oscillations is given by

as Assuming the damping rate is

in first approximation as If as in Figure 5, increases linearly with

Figure 5.

Stabilizing effect of the delayed feedback. Equations (3) and (4) have been simulated numerically with increasing values of and with the initial conditions and ( The fixed parameters are (a) , (b) , (c)

3. Small Delay Limit

Statz et al. [8]’s strategy for eliminating undesired laser oscillations is based on the observation that the roots of the characteristic equation are real and negative if in the case of zero delay. In other words, the decay towards the stable steady state is purely exponential if the feedback gain is sufficiently large. Provided that the delay is small, the authors reasonably expected the same transient evolution to the steady state. Krivoshchekov et al. [15] expanded the delayed variable for small as

They then analyzed the stability of the steady state. Instead of (7), the characteristic equation is

The stability condition is

Using Table A2 in Appendix B, (26) can be rewritten in terms of the original parameters as

which is the inequality (5) in [15]. From (25), we determine the conditions for real roots given by

The expansion (24) however does not lead to the second LP because is large The limit where as is however interesting because it suggests that a small delay may lead to sustained oscillations provided the negative feedback rate is sufficiently large. A careful analysis of the linearized equations evaluated at the Hopf bifurcation point suggests the following scalings as

Inserting (28) into Equations (5) and (6) leads to the following equations for and y

In the limit Equation (29) reduces to

which we recognize as Wright equation [22] (or equivalently, the delayed logistic equation, after the change of variable ). This specific limit is documented in [23] (p. 117). Oscillations emerge at with a period and quickly becomes pulsating as is further increased.

4. Discussion

The interest of purely negative real eigenvalues of a DDE is rarely emphasized in the DDE literature essentially devoted to the conditions of oscillatory instabilities. They do, however, play a role in applications, and they strongly depend on the delay.

It is quite remarkable that in 1965, a DDE was analyzed in order to understand how to eliminate undesirable oscillations by using a delayed feedback. Statz et al. [8] were exploring the conditions for purely real eigenvalues as means to obtain exponentially decaying transients. From their experiments and their numerical simulations, they conclude that the delay should be small, and that the feedback gain needs to be sufficiently large. In this paper, we substantiate their findings analytically by determining the conditions

where and admit the approximations (13) and (14) for small delays, respectively, and is given by (12).

The damping rate of the natural laser oscillations is small like for the ruby laser, but also for other solid state and semiconductor lasers. In our analysis, we neglect its contribution because the delay term dominates the stability conditions as the feedback rate is increased. However, there are other problems where the damping rate could be moderate to large. Consider, for example, the delayed Duffing equation, which has benefited from recent mathematical interests [24,25,26]. Duffing equation models an elastic pendulum whose spring’s stiffness is nonlinear. Supplemented by a delayed velocity control term, it is given by

The linearized problem leads to the characteristic equation

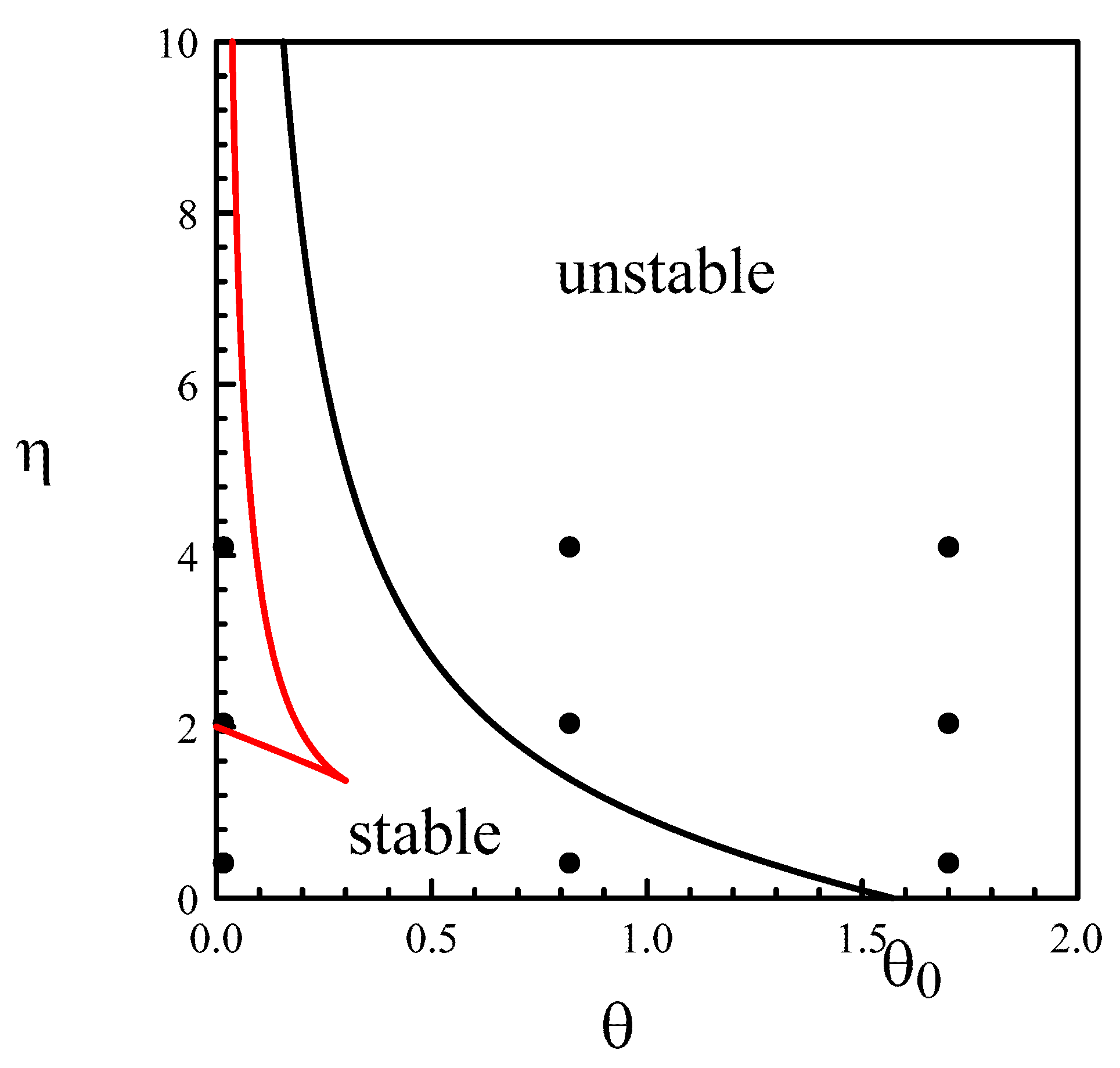

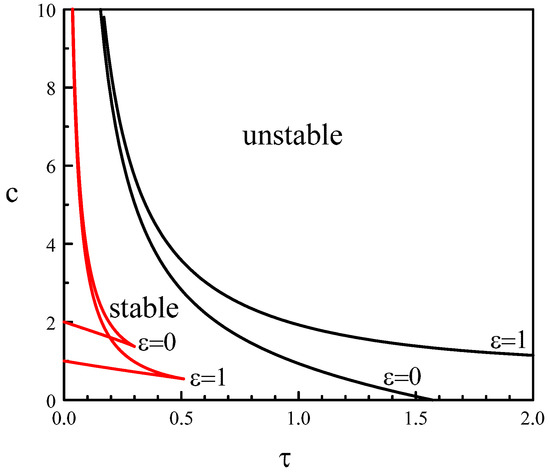

which is Equation (7) supplemented by the term. The analysis of the real and purely imaginary roots of Equation (34) is similar to our previous analysis with In Figure 6, we contrast the stability diagrams of and The domain of purely exponential decay increases with , while the change of stability through a Hopf bifurcation moves to higher delays. This is expected because the damping term contributes to stabilizing the zero solution.

Figure 6.

Stability diagram for the delayed Duffing equation. The first Hopf bifurcation line delimits the domain of stable steady states (black). It contains a smaller domain where the decay to the steady state is purely exponential (red).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A.V.K. and E.A.V. were supported by the Government of Russian Federation (grant 08-08).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. The DDE Problem of Statz et al.

Equations (9) and (10) of Statz et al. [8] for the intensity of the laser field u and the inverted population v are

u and v are normalized such that is the non-zero intensity steady state in the absence of feedback (). The dimensionless time is the original time variable multiplied by the angular optical frequency is the quality factor of the cavity and where is approximately the fluorescent life time. is the dimensionless delay and is the estimated value of the pump parameter. The values of the feedback amplitude b and delay used in the simulations are [8]

In the experiments, a feedback circuit is used with a minimum delay of . In terms of the original delay the delays considered in the simulations are and are of the same range as the delay of the feedback control circuit. The experiments considered a feedback amplitude of approximately and motivated the values of b detailed in (A3).

One parameter can be eliminated by reformulating Equations (A1) and (A2). Specifically, we introduce the new variable D, I and parameter A defined as

Inserting (A4) into Equations (A1) and (A2), we obtain

where

The values of the feedback amplitude are identical to the values of b shown in (A3). The values of the delay corresponding to the values of listed in (A3) are

Equations (A5) and (A6) are the classical rate equations for a Class B laser exhibiting a small [21] The non-zero intensity steady state is given by

We next introduce the basic time scale of the laser equations given by

where is the laser relaxation oscillation frequency defined by

After introducing (A11) into Equations (A5) and (A6), we introduce the new variables x and y defined as the deviations from D and I from their steady state values. Specifically, x and y are related to and as

In terms of s, x and y, Equations (A5) and (A6) become

where the values of the parameters are listed in Table A1. Equations (A14) and (A15) are now in an ideal form for analysis.

Table A1.

Dimensionless parameters and their values.

Table A1.

Dimensionless parameters and their values.

| , | |

Appendix B. The DDE Problem of Krivoshchekov et al.

Equations (1) and (2) of Krivoshchekov et al. [15] are given by

where

Introducing

into Equations (A16) and (A17), we obtain

where the new parameters are

The steady state satisfies

Introducing the new variables x, y and s defined by

we obtain

where the definitions and the values of the parameters are listed in Table A2. Except for the feedback amplitude the definitions of and are the same as for Statz et al. equations (see Table A1).

Table A2.

Dimensionless parameters and their values.

Table A2.

Dimensionless parameters and their values.

References

- Makhov, G.; Kikuchi, C.; Lambe, J.; Terhune, R.W. Maser action in ruby. Phys. Rev. 1958, 109, 1399–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, C.; Lambe, J.; Makhov, G.; Terhune, R.W. Ruby as a maser material. J. Appl. Phys. 1959, 30, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiman, T.H. Stimulated optical radiation in ruby. Nature 1960, 187, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.J.; Nelson, D.F.; Schawlow, A.L.; Bond, W.; Garrett, C.G.B.; Kaiser, W. Coherence, narrowing, directionality, and relaxation oscillations in the light emission from ruby. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1960, 5, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.F.; Boyle, W.S. A continuously operating ruby optical maser. Appl. Opt. 1962, 1, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statz, H.; DMars, G. Transients and Oscillation Pulses in Masers. In Quantum Electronics; Townes, C.H., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960; pp. 530–537. [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmuir, R. Theory of relaxation oscillations in optical masers. J. Elerctron. Control 1981, 10, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staz, H.; DeMars, G.A.; Wilson, D.T. Problem of spike elimination in lasers. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 30, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozyk, J. Observations on a concentric spherical cavity laser oscillator. IEEE J. Quantum. Electr. 1967, 3, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koechner, W. Solid-State Laser Engineering, 6th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, F.R.; Roberts, D.L. Use of electro-optical shutters to stabilize ruby laser operation. Proc. IRE 1962, 50, 2108. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, D.V.; Davis, B.I. High power non-spiking operation of ruby laser. IEEE J. Quantum. Electr. 1966, QE-2, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.H.; Price, E.V. Feedback control of a Q-switched ruby laser. IEEE J. Quantum. Electr. 1966, QE-2, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovberg, R.V.; Wooding, E.R.; Yeoman, M.L. Pulse stretching and shape control by compound feedback in a Q-switched ruby laser. IEEE J. Quantum. Electr. 1975, QE-11, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoshchekov, G.V.; Makukha, V.K.; Tarasov, V.M. Stabilization of ruby laser radiation by an external negative feedback. Sov. J. Quantum Electron. 1975, 5, 394–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, R.F. Self modulation at gigahertz frequencies of a diode laser coupled to an external cavity. Electron. Lett. 1969, 5, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, R.; Mohn, E.; Risch, C.; Salathe, R. Microwave self-modulation of a diode laser coupled to an external cavity. IEEE J. Quantum Electr. 1970, 6, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.M.; Shore, K.A. Unlocking Dynamical Diversity: Optical Feedback Effects on Semiconductor Lasers; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, M.C.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Mirasso, C.R.; Fischer, I. Complex photonics: dynamics and applications of delay-coupled semiconductor lasers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 421–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chembo, Y.K.; Brunner, D.; Jacquot, M.; Larger, L. Optoelectronic oscillators with time-delayed feedback. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2019, 91, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erneux, T.; Glorieux, P. Laser Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.L. An Introduction to Delay Differential Equations with Applications to the Life Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorieva, E.V.; Kaschenko, S.A. Asymptotic Representation of Relaxation Oscillations in Lasers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Davidow, M.; Shayak, B.; Rand, R.H. Analysis of a remarkable singularity in a nonlinear DDE. Nonlear Dyn. 2017, 90, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.M.; Fiedler, B.; Shayak, B.; Rand, R.H. Unbounded sequences of stable limit cycles in the delayed Duffing equation: An exact analysis. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.06533. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, B.; Ĺopez Nieto, A.; Rand, R.H.; Sah, S.M.; Schneider, I.; de Wolff, B. Coexistence of infinitely many large, stable, rapidly oscillating periodic solutions in time-delayed Duffing oscillators. J. Differ. Equ. 2020, 268, 5969–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).