Abstract

Commutation is a judicial policy that is implemented in most countries. The recidivism rate of commuted prisoners directly affects people’s perceptions and trust of commutation. Hence, if the recidivism rate of a commuted prisoner could be accurately predicted before the person returns to society, the number of reoffences could be reduced; thereby, enhancing trust in the process. Therefore, it is of considerable importance that the recidivism rates of commuted prisoners are accurately predicted. The dynamic adjusting novel global harmony search (DANGHS) algorithm, as proposed in 2018, is an improved algorithm that combines dynamic parameter adjustment strategies and the novel global harmony search (NGHS). The DANGHS algorithm improves the searching ability of the NGHS algorithm by using dynamic adjustment strategies for genetic mutation probability. In this paper, we combined the DANGHS algorithm and an artificial neural network (ANN) into a DANGHS-ANN forecasting system to predict the recidivism rate of commuted prisoners. To verify the prediction performance of the DANGHS-ANN algorithm, we compared the experimental results with five other forecasting systems. The results showed that the proposed DANGHS-ANN algorithm gave more accurate predictions. In addition, the use of the threshold linear posterior decreasing strategy with the DANGHS-ANN forecasting system resulted in more accurate predictions of recidivism. Finally, the metaheuristic algorithm performs better searches with the dynamic parameter adjustment strategy than without it.

1. Introduction

Parole is the temporary and conditional release of a prisoner prior to the completion of their maximum sentence period. Commutation is the substitution of a lesser penalty for that originally given at the time of conviction. However, whether on parole or commutation, if the prisoner reoffends it can cause social disruption. This highlights the need for accurate recidivism predictions for parolees and commutation offenders. Carroll et al. [1] stated that “in Pennsylvania, the parolees with alcohol problems, younger parolees, and those originally convicted of property crimes (rather than assaultive or drug crimes) were more likely to commit new crimes on parole. Offenders with past heroin use were convicted of more serious crimes on parole. Absconding was significantly more predictable for cases with prior convictions, previous parole violations, and miscellaneous negative statements by the institution about the inmate’s personality.” In Williams’ paper [2], they demonstrated that in California, non-sex offenders, drug registrants, offenders with more than one felony conviction, frequently unemployed offenders, offenders with unstable living arrangements, offenders aged 25 to 30, previous parole violators, and unmarried offenders were more likely to abscond without leave. MacKenzie and Spencer [3] showed that in northern Virginia, offenders committed more crimes when they had high-risk behaviors such as using drugs, alcohol abuse, and carrying a gun; conversely, they committed fewer crimes when they were employed or lived with spouses. In Benda’s paper [4], the findings indicated that caregiving factors have an inverse relationship with the rate of recidivism. Therefore, low self-control, drug use and sales, gang membership, peer association with criminals, carrying weapons, and poor social skills have a positive relationship with recidivism rates. Trulson et al. [5] stated that “generally, males, those younger at first contact with the juvenile justice system, those with a greater number of felony adjudications, gang members, institutional dangers, those in poverty, and those with mental health issues were significantly more likely to recidivate.” Previous studies have focused on qualitative research or statistical analysis. However, over the past two decades, many artificial intelligence methods, such as the artificial neural network (ANN) [6,7], support vector machine (SVM) [8], association rule (AR) [9], etc., have been developed and applied in many problems. Among these methods, the artificial neural network has been widely used to solve numerous types of forecasting problems and could derive a better accuracy than SVM in supervised learning [8,10]. Therefore, this paper adopted ANN as its forecasting tool.

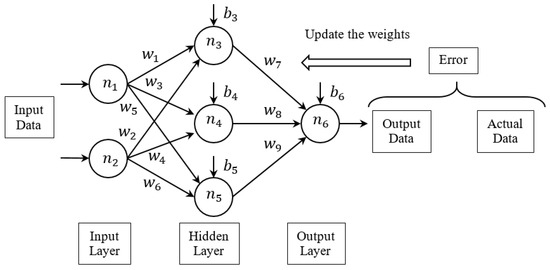

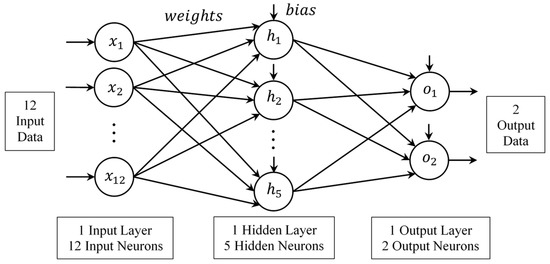

An ANN is a computational mechanism that is inspired by the human brain. A typical ANN structure, also known as a multilayer perceptron (MLP), contains a number of layers each composed of several basic components. The first layer is called input layer; the last layer is called output layer, and the other layers are hidden layers [11]. There are two types of basic components in a typical neural-network structure, namely, neurons and the links between them, as shown in Figure 1. The neurons are the processing elements, and the links are the interconnections. Every link has a corresponding weight parameter or bias parameter. When a neuron receives stimuli from other neurons via the links, it processes the information and produces an output. There are three kinds of neurons, and as per the layers, they are categorized as input, hidden, and output. Input neurons receive stimuli from outside the network. Hidden neurons receive stimuli from neurons at the front of the network and relay the output to neurons at the back of the network. Output neurons transfer the output externally [12].

Figure 1.

Typical neural-network structure.

In the ANN system, the weights were updated by a systemic algorithm during the learning process. The backpropagation (BP) learning algorithm is the most popular procedure for training an ANN [13]. Initially, the weights and biases are assigned randomly. The BP uses gradient descent to search the point(s) with minimum error on an error surface (error as a function of the ANN weights and biases). In other words, the weights and biases are updated using the error, which is calculated with the output and actual data. Once the neural network training was completed, we could predict or classify new data using the calculation with the received stimuli (the new input data), the weights, and the biases. However, the gradient descent, i.e., the learning process of the backpropagation network (BPN), is easy to trap within the local optimum.

To eradicate the aforementioned disadvantage of BPN, combinations of different metaheuristic algorithms and ANN (metaheuristic-ANN) are used, as presented in many studies. Kattan and Abdullah [14] trained the ANNs for pattern-classification problems using the harmony search (HS) algorithm. Tavakoli et al. [11] used the HS-ANN, novel global harmony search ANN (NGHS-ANN), and intelligent global harmony search ANN (IGHS-ANN) for three well-known classification problems. Kumaran and Ravi [15] combined the ANN and the HS algorithm for forecasting long-term, sector-wise electrical energy use. Göçken et al. [16] integrated metaheuristic and ANN algorithms for improved stock price prediction. In these papers, the results showed that metaheuristic-ANN has a better forecasting ability than BPN. Moreover, in the past two decades, HS and varied HS algorithms have been widely proposed, discussed, and applied to many studies. Therefore, we combined different HS and ANN algorithms in this paper.

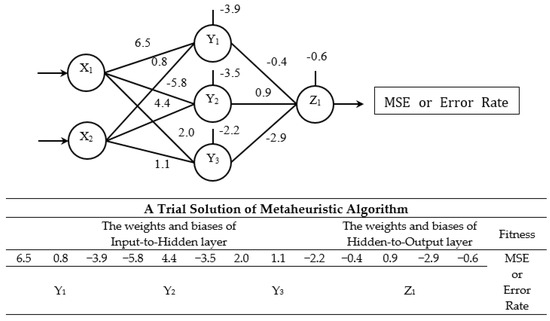

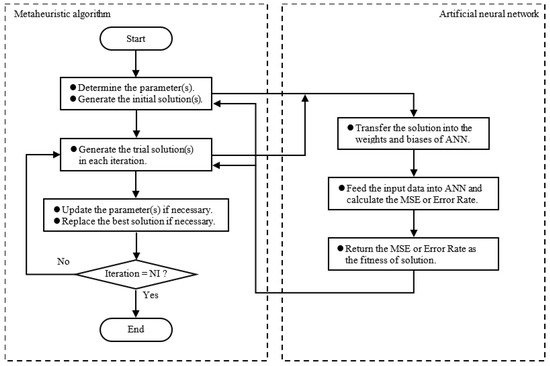

Metaheuristic-ANN involves a trial solution of metaheuristic algorithms with set weights and biases. Metaheuristic-ANN used a random search mechanism to determine the best weights and biases to minimize forecasting error, such as the mean squared error (MSE), the error rate, and so on. Figure 2 shows a small sample presenting the relationship between a metaheuristic algorithm and ANN. There are two input neurons, three hidden neurons, and one output neuron in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows the procedure of Metaheuristic-ANN. The MSE and error rates are given in Equations (1) and (2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between metaheuristic algorithm and artificial neural network (ANN).

Figure 3.

Procedure of Metaheuristic-ANN.

A dynamic adjusting novel global harmony search (DANGHS) algorithm [17], as proposed in 2018, is a novel metaheuristic algorithm that combines a novel global harmony search (NGHS) [18,19,20] with dynamic adjusting parameter strategies. In NGHS, the value of the genetic mutation probability () is a fixed given value. However, the searching ability of a metaheuristic algorithm can be improved by the appropriate parameters; the importance of which has been described in many studies [11,18,19,20,21,22]. Therefore, in DANGHS, the genetic mutation probability is dynamically adjusted for each iteration. Chiu et al. [17] found that the DANGHS algorithm is more efficient and effective than other HS algorithms. However, in their paper, they used the DANGHS algorithm to solve 14 benchmark continuous optimization problems only. In this paper, we would like to investigate the searching performance of DANGHS algorithm further. Therefore, a DANGHS-ANN recidivism forecasting system was proposed for the purposes of this paper. According to the numerical results, the DANGHS-ANN system provided more accurate forecasts than the five other systems (BPN, HS-ANN, IHS-ANN, SGHS-ANN, and NGHS-ANN).

The remainder of this paper is divided into three sections. Section 2 introduces the harmony search (HS), improved harmony search (IHS), self-adaptive global best harmony search (SGHS), novel global harmony search (NGHS), and dynamic adjusting novel global harmony search (DANGHS) algorithms. Section 3 discusses the experiments carried out to test and compare the performances of the six forecasting systems. Conclusions and suggestions for future research are provided in Section 4.

2. A Review of Five Harmony Search Algorithms

In this section, HS, IHS, SGHS, NGHS, and DANGHS are reviewed.

2.1. Harmony Search Algorithm

Geem, Kim, and Loganathan [23] first proposed the HS algorithm in 2001. In concept, HS is similar to other metaheuristic algorithms such as genetic algorithm (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and ant colony optimization (ACO). These algorithms combine the rules of randomness to imitate the processes that inspired them. The HS algorithm draws its inspiration from the improvisation process of musicians, such as a jazz trio, and not from biological or physical processes [11,14].

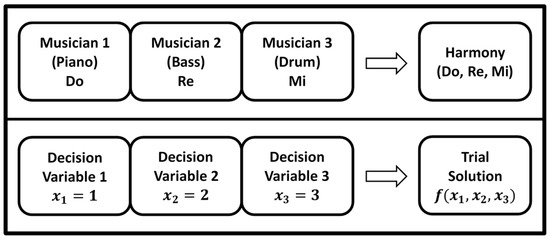

In musical improvisation, musicians play pitches within a set range, and then combine and order them to form a harmony. If the harmony is pleasant, it is stored in each musician’s memory thereby increasing the possibility of performing it again in the future [24]. Similarly, in engineering optimization, each decision variable initially selects a value within a given, feasible range, and then combines all the variables together to give a single solution vector [20]. In the HS algorithm, the trial solution (harmony) for the problem is be comprised of several decision variable values (pitches). Thus, a pleasing harmony means a good trial solution to the problem [11]. If all the decision variable values compose a good trial solution, then the decision variable values are stored in each variable’s memory. Therefore, the possibility of generating a good solution in the future is increased [20]. Figure 4 shows a comparison between music improvisation and engineering optimization. In Figure 4, each musician of the jazz trio plays an instrument simultaneously to form a harmony. The pitch of the piano represents the value of the decision variable 1.

Figure 4.

Comparison between music improvisation and engineering optimization.

The HS algorithm consists of several parameters. These parameters are the harmony memory size (m), the harmony memory considering rate (HMCR), the pitch adjusting rate (PAR), the bandwidth (BW), and the maximum number of iterations (NI). Among these parameters, the HMCR, PAR, and BW are particularly important because the HS generates a new trial solution from harmony memory (HM) or random selection according to the HMCR, and then the HS adjusts the new trial solution using the PAR and BW. The whole search process of HS algorithm can be described as the following steps.

- Step 1: Determine the problem and initial algorithm parameters, including m, HMCR, PAR, BW, current iteration = 1, and NI.

- Step 2: Generate the initial solutions (harmony memory) randomly and calculate the fitness of each solution.

- Step 3: Generate a trial solution by HMCR, PAR, and BW. The pseudocode of HS algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 The Pseudocode of HS |

| 1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: 7: 8: 9: 10: 11: 12: 13: 14: 15: |

Here, D represents the number of problem dimensions. , , and represent the random numbers in the region of [0, 1]. represents the jth component of the ith solution in current iteration . represents the lower bound for decision variables , and represents the upper bound.

- Step 4: If the trial solution is better than the worst solution in the HM, replace the worst solution by the trial solution.

- Step 5: If the maximum number of iterations NI is satisfied, return the best solution in the HM; otherwise, the current iteration = + 1 and go back to step 3.

2.2. Improved Harmony Search Algorithm

Mahdavi, Fesanghary, and Damangir [25] presented the IHS algorithm in 2007 for solving optimization problems. The main difference between IHS and the traditional HS method is that two key parameters are adjusted in each iteration, demonstrated by Equations (3) and (4). These parameters are PAR and BW. In their paper, they state that PAR and BW are important parameters to search decision variable values. These two parameters can potentially be useful in speeding up the convergence rate of the HS to the optimal solution. Therefore, the fine adjustment of these parameters is of particular interest.

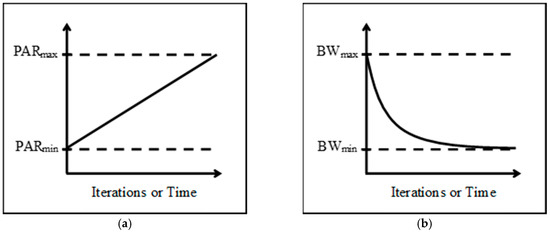

In Equation (3), represents the pitch adjustment rates in the current iteration ; is the minimum adjustment rates, and is the maximum adjustment rates. In Equation (4), is the distance bandwidth in current iteration ; is the minimum bandwidth, and is the maximum bandwidth. Figure 5 shows that the PAR and BW values vary dynamically with the iteration number.

Figure 5.

(a) Linear variation of pitch adjusting rate (PAR) with the iteration number; (b) nonlinear variation of bandwidth (BW) with the iteration number.

2.3. Self-Adaptive Global Best Harmony Search Algorithm

In 2010, Pan et al. [21] introduced the SGHS algorithm for continuous optimization problems. The main difference between the SGHS and traditional HS method is that HMCR and PAR are dynamically adjusted using a normal distribution and BW is altered for each iteration.

In each iteration , SGHS generated the value of by the mean HMCR () and its standard deviation. Similarly, the value of was calculated by the mean PAR () and its standard deviation. In their paper, the is in the range of [0.9, 1.0] and the standard deviation of HMCR is 0.01; the is in the range of [0.0, 1.0] and the standard deviation of PAR is 0.05.

Furthermore, when the generated harmony was better than the worst harmony in HM, SGHS recorded the and . After a specified learning period (LP), SGHS recalculated the by averaging all the recorded values during the learning period. In the same way, was recalculated by averaging all the recorded values. In subsequent iterations, SGHS generated new and values by the new , , and the given standard deviation.

In addition, was decreased in the first half iterations in Equation (5), and then was a fixed value () in the second half iterations.

The whole search process of SGHS algorithm can be described as the following steps.

- Step 1: Determine the problem and initial algorithm parameters, including m, ,, , , LP, current iteration = 1, and NI.

- Step 2: Generate the initial solutions (harmony memory) randomly and calculate the fitness of each solution.

- Step 3: Generate the algorithm parameters in current iteration , including , , and .

- Step 4: Generate a trial solution by , , and . The pseudocode of SGHS algorithm is shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 The Pseudocode of SGHS [21] |

| 1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: 7: 8: 9: 10: 11: 12: 13: 14: 15: |

Here, represents the jth component of the best solution in current iteration .

- Step 5: If the trial solution is better than the worst solution in the HM, replace the worst solution by the trial solution and record the values of HMCR and PAR in current iteration .

- Step 6: Recalculate the and .

- Step 7: If the maximum number of iterations NI is satisfied, return the best solution in the HM; otherwise, the current iteration = + 1 and go back to Step 3.

2.4. Novel Global Harmony Search Algorithm

Zou et al. proposed the NGHS algorithm in 2010 for task assignment problems [18], continuous optimization problems [19], and unconstrained problems [20]. The NGHS algorithm is an improved algorithm that combines HS, PSO [26,27,28,29], and GA [30,31,32]. A prominent characteristic of PSO is that individual particles attempt to imitate the social experience. This means that the particles are affected by other better particles in the PSO algorithm. A prominent characteristic of GA is that it is possible for the trial solution to escape from the local optimum by mutation. In other words, NGHS tries to generate a new trial solution by moving the worst solution toward the best solution or by mutation. In addition, HMCR, PAR, and the BW are excluded from NGHS, while the genetic mutation probability () is included. Moreover, NGHS replaces the worst solution in HM with a new solution, even if the new solution is worse than the worst solution. The above three characteristics are the key differences between HS and NGHS algorithms. The whole search process of NGHS algorithm can be described as the following steps.

- Step 1: Determine the problem and initial algorithm parameters, including m, , current iteration = 1, and NI.

- Step 2: Generate the initial solutions (harmony memory) randomly and calculate the fitness of each solution.

- Step 3: Generate a trial solution by . The pseudocode of NGHS algorithm is shown in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 The Pseudocode of NGHS [18,19,20] |

| 1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: 7: 8: 9: 10: 11: 12: |

Here, represent the trust region. represents the jth component of the worst solution in current iteration .

- Step 4: Replace the worst solution by the trial solution, even if the trial solution is worse than the worst solution.

- Step 5: If the maximum number of iterations NI is satisfied, return the best solution in the HM; otherwise, the current iteration = + 1 and go back to Step 3.

2.5. Dynamic Adjusting Novel Global Harmony Search

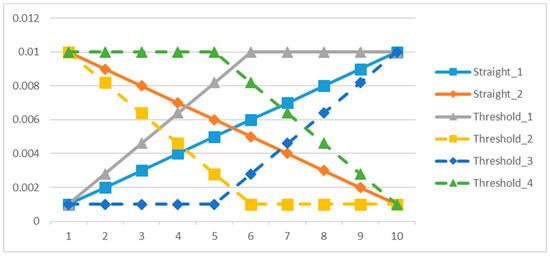

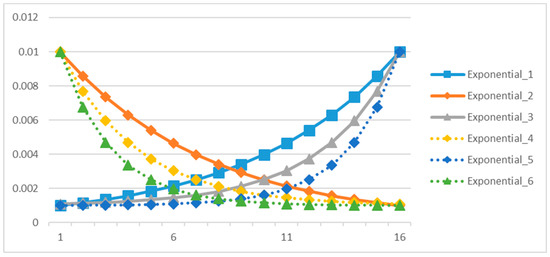

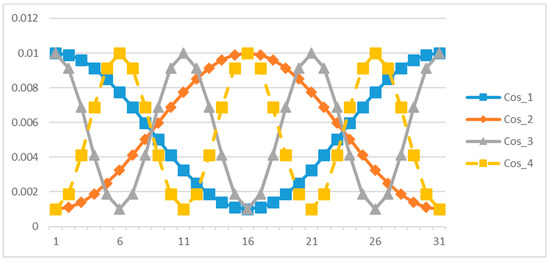

Chiu et al. [17] firstly proposed the DANGHS algorithm for continuous optimization problems. As mentioned above, the main difference between DANGHS and NGHS is that the parameter, mutation probability (), is dynamically adjusted in each iteration by the adjustment strategy. However, Chiu et al. pointed out that the mutation probability can be adjusted using different strategies. Hence, there are 16 different strategies investigated in their paper. All 16 strategies are shown in Table 1, and Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 are used to illustrate them. In Table 1, is the mutation probability in the current iteration , is the minimum genetic mutation probability, is the maximum genetic mutation probability, is the modification rate, and is the coefficient of cycle.

Table 1.

Sixteen dynamic adjustment strategies.

Figure 6.

Straight linear and threshold linear strategies.

Figure 7.

Exponential strategies.

Figure 8.

Concave cosine and convex cosine strategies.

3. Experiments and Analysis

3.1. Data Setting

The investigation samples were provided by the Information Department of the Taiwan Ministry of Justice. The samples are criminal tracing records established over three years, from July 16, 2007 to July 15, 2010. The data is solely used for academic research on predicting recidivism. In order to ensure personal privacy, the samples were preprocessed (deidentification).

The total number of samples collected for this paper was 9498. Of the samples, 8569 were male and 929 were female. For the purposes of this paper, the definition of recidivism was “having a record of prosecution.” Of the samples collected, 5408 (56.94%) were recidivists and 4090 (43.06%) were non-recidivists. The input and output variables that were used are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Input and output variables.

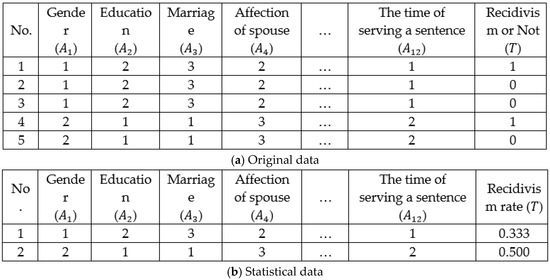

Of the original 9498 samples, some were found to have the same combination of input variables, but had different output variables, as shown in Figure 9a. Such samples make it impossible to accurately train the ANN. Therefore, in this paper, we used a statistical method to recalculate the output variable as the recidivism rate, as shown in Figure 9b. After recalculation, the total number of samples was 6825. A recidivism rate above or equal to 0.5 was defined as high, and a rate below 0.5 was defined as low, as shown in the last column of Table 2.

Figure 9.

Example of the original data and the statistical data. (a) Original data; (b) statistical data.

Lastly, proper data representation plays an important role in the design of a successful ANN [33]. Therefore, the output variable was categorized according to two binary numbers which represented the rate of recidivism where 10 represented a low rate, 01 a high rate, and all data in between 0.1 and 0.9 were standardized. Hence, there are 12 and 2 neurons in the input and output layers, respectively.

3.2. Computing Environment Settings

We used Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 C# (64-bit) as the compiler for writing the program to find the solution. The solution-finding equipment comprised an Intel Core (TM) i7-4720HQ (2.6 GHz) CPU, 8 GB of memory, and Windows 10 home edition (64-bit) OS.

3.3. Experimental Structure and Results of BPN

In the BPN experiments, 65% of the samples were used for training, 25% for validation, and 10% for testing [34]. However, the performance of the forecasting system could be affected by the quality of the training samples. To prevent this, previously conducted studies have used K-fold cross validation. In this paper, we also used K-fold cross validation (K = 10) for repeated experiments to verify the robustness of the experimental results under different training samples. In each K-fold experiment, 30 independent experiments were carried out. The total number of training iterations (epochs) is 10,000. The number of hidden layers used is one, and the number of hidden neurons (NHN) is set at five in Equation (6) [33]. In Equation (6), represents the number of input neurons, and represents the number of output neurons. Therefore, the total number of weights and biases are 77, and the example-to-weight ratio (EWR) is 88.64, as calculated in Equation (7). Dowla and Rogers [35] and Haykin [36] found that the EWR needs to be larger than 10. Hence, in this paper, the ANN is of a reasonable and acceptable structure. Figure 10 shows the MLP structure used in this paper.

Figure 10.

Multilayer perceptron structure.

For the purposes of this study, the investigation is a classification problem, in which the forecasting output is either of a high (10), or low (01), recidivism rate. Therefore, the prediction error used is the error rate, as given in Equation (2).

Lastly, we used the trial and error method to decide the best learning rate (η) and momentum (α) of BPN. We define three kinds of learning rate, which are 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3. However, Zupan and Gasteiger suggest the learning rate and the momentum are equal to 1 [37]. Therefore, the three kinds of momentum are 0.9, 0.8, and 0.7. The trial and error experimental results are shown in Table 3. In Table 3, LR represents the learning rate, MT represents the momentum, Std represents the standard deviation, and each value represents the mean error rate of 30 independent experiments. For example, 3.37 × 10−1 represents the mean error rate of 30 independent experiments where LR is set to 0.1, MT is set to 0.9, and K is set to 1. Based on the mean (3.25 × 10−1, 3.53 × 10−1, and 3.52 × 10−1) and the p-value, we can observe that the error rate (where the learning rate is set to 0.1 and the momentum is set to 0.9) is significantly smaller than the other two parameter combinations in the training, validation, and testing datasets.

Table 3.

Trial and error experimental results of backpropagation network (BPN).

3.4. Experimental Results of the Metaheuristic-ANN Forecasting System

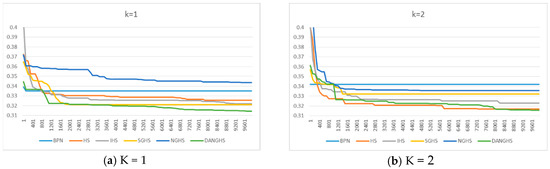

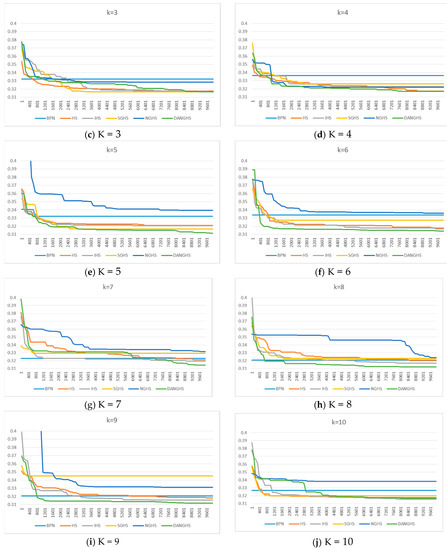

We combined the DANGHS algorithm with ANN (DANGHS-ANN) to solve the recidivism rate prediction problem. In order to verify the performance of the DANGHS-ANN forecasting system, we compared the extensive experimental results of DANGHS-ANN with five other systems, including various HS-ANNs and one BPN. We referred to previous references [17,20,21,22] and used the trial and error method to decide the parameters of different HS algorithms. The parameters of the compared HS algorithms are shown in Table 4. In each algorithm, in each K-fold experiment, thirty independent experiments (n) were carried out with 10,000 iterations. There was no overtraining detected in the metaheuristic-ANN forecasting system. Therefore, we combined the training and validation datasets into the learning dataset. This means that 90% of the samples were used for learning and 10% for testing. The experimental results from the learning and testing datasets, obtained using the 16 different adjustment strategies in the DANGHS-ANN forecasting system, are shown in Table 5 and Table 6. The experimental results from the learning and testing datasets, as obtained using the six different forecasting systems, are shown in Table 7 and Table 8. Figure 11 presents a typical solution history graph of the six different forecasting systems along with the various iterations. Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14 present the comparison between actual and predictive recidivism for the six forecasting systems.

Table 4.

Parameters of compared harmony search (HS) algorithms.

Table 5.

Experimental results of learning dataset of 16 strategies in the DANGHS-ANN systems.

Table 6.

Experimental results of testing dataset of 16 strategies in the DANGHS-ANN systems.

Table 7.

Experimental results of learning dataset of six forecasting systems.

Table 8.

Experimental results of testing dataset of six forecasting systems.

Figure 11.

Typical convergence graph of six different forecasting systems. (a) K = 1; (b) K = 2; (c) K = 3; (d) K = 4; (e) K = 5; (f) K = 6; (g) K = 7; (h) K = 8; (i) K = 9; (j) K = 10.

Table 9.

Comparison between the actual and predictive recidivism in BPN system.

Table 10.

Comparison between the actual and predictive recidivism in HS-ANN system.

Table 11.

Comparison between the actual and predictive recidivism in IHS-ANN system.

Table 12.

Comparison between the actual and predictive recidivism in SGHS-ANN system.

Table 13.

Comparison between the actual and predictive recidivism in NGHS-ANN system.

Table 14.

Comparison between the actual and predictive recidivism in DANGHS-ANN system.

In Table 5, several experimental results are given. Firstly, in the learning dataset where K = 1, the error rate (3.1190 × 10−1) with threshold linear posterior decreasing strategy (Threshold_4) is lower than those of the other strategies. Secondly, the mean of error rate (3.1132 × 10−1) with Threshold_4 is the lowest of all strategies. Thirdly, the standard deviation (1.2896 × 10−6) where Threshold_4 is lower than those of the other strategies. Lastly, according to the p-value, the error rate for Threshold_4 is significantly lower than those of the other strategies, except for the straight linear decreasing strategy (Straight_2).

In Table 6, several experimental results are given. Firstly, in the testing dataset where K = 1, the error rate (3.3934 × 10−1) with the threshold linear posterior decreasing strategy (Threshold_4) is lower than those of the other strategies. Secondly, the mean of error rate (3.3878 × 10−1) with Threshold_4 is the lowest of all the strategies. Thirdly, the standard deviation (3.2137 × 10−5) with the threshold linear prior increasing strategy (Threshold_1) is lower than those of the other strategies. However, according to the p-value, the error rate with Threshold_4 is significantly lower than those of the other strategies, except for strategy Straight_2. Based on the experimental results in Table 5 and Table 6, the best strategy for the DANGHS-ANN forecasting system, and specifically for the recidivism prediction problem, is the threshold linear posterior decreasing strategy.

In Table 7, several experimental results are given. Firstly, in the learning dataset, the DANGHS-ANN error rates are the lowest of all the other forecasting systems, for all K-fold experiments. Additionally, the DANGHS-ANN mean of error rate (3.1132 × 10−1) and standard deviation (1.1356 × 10−3) are the lowest of all the forecasting systems. This means that the forecasting ability of the DANGHS-ANN system is relatively robust. Also, according to the p-value, the DANGHS-ANN error rate is significantly lower than the other systems in the learning dataset. The mean of error rate of the IHS-ANN system (3.1315 × 10−1) is lower than that of the HS-ANN system (3.1357 × 10−1), and the mean of error rate of the DANGHS-ANN system (3.1132 × 10−1) is lower than that of the NGHS-ANN system (3.1545 × 10−1).

In Table 8, several experimental results are given. Firstly, in the testing dataset, most of the DANGHS-ANN error rates are smaller than those of the other forecasting systems, except where K = 2 and K = 7. Where K = 2 and K = 7, the IHS-ANN system has the lowest error rate (3.3982 × 10−1 and 3.4056 × 10−1). Secondly, the DANGHS-ANN mean of error rate (3.3878 × 10−1) is lower than those of the other forecasting systems. Thirdly, the SGHS-ANN standard deviation (5.7819 × 10−3) is the lowest of all the forecasting systems. This means that the forecasting ability of the SGHS-ANN system is relatively robust. However, according to the p-value, the error rate of the DANGHS-ANN system is significantly lower than the other systems in the testing dataset. Lastly, the IHS-ANN mean of error rate (3.4039 × 10−1) is lower than that of the HS-ANN system (3.4126 × 10−1), and the DANGHS-ANN mean of error rate (3.3878 × 10−1) is lower than that of the NGHS-ANN system (3.4421 × 10−1).

In Figure 11, four experimental results are given. Firstly, the BPN system graph displays a horizontal line, this means that it would easily fall within the local optimum, and unlikely escape it. According to the SGHS-ANN and NGHS-ANN graphs, they also easily fall within the local optimum in the latter iterations. However, the HS-ANN, IHS-ANN, and DANGHS-ANN graphs show that these three systems continuously decrease the error rate as the iterations progress. Moreover, according to the NGHS-ANN and DANGHS-ANN graphs, we find that the DANGHS-ANN error rate is lower than that of the NGHS-ANN system. In other words, the DANGHS-ANN system has a better forecasting ability than the NGHS-ANN system.

Finally, we analyze and discuss the comparison between actual and predictive recidivism. In Table 9, the number of predictions of low recidivism by the BPN system is 2652, of which the actual number of high recidivisms is 886, and the rate of high recidivism is 33.41%. In Table 10, the number of predictions of low recidivism by the HS-ANN system is 2596, of which the actual number of high recidivisms is 841, and the rate of high recidivism is 32.40%. In Table 11, the number of predictions of low recidivism by the IHS-ANN system is 2397, of which the actual number of high recidivisms is 767, and the rate of high recidivism is 32.00%. In Table 12, the number of predictions of low recidivism by the SGHS-ANN system is 2807, of which the actual number of high recidivisms is 931, and the rate of high recidivism is 33.17%. In Table 13, the number of predictions of low recidivism by the NGHS-ANN system is 2401, of which the actual number of high recidivisms is 792, and the rate of high recidivism is 32.99%. Lastly, in Table 14, the number of predictions of low recidivism by the DANGHS-ANN system is 2508, of which the actual number of high recidivisms is 798, and the rate of high recidivism is 31.82%.

Particular attention is paid to the decisions made for managing the prisoners. For example, the management decision for prisoners predicted to fall within the high recidivism category is to “continue serving their sentences.” Therefore, this kind of decision will positively affect the safety of the public. Conversely, prisoners that are predicted to fall within the low recidivism category will re-enter society by commutation or parole. Their behavior thereafter could directly affect the safety of the public. The purpose of this paper is to develop a recidivism rate forecasting system to reduce the associated reoffences and improve public acceptance of commutation and parole policies. According to the above argument, the type I error of the traditional presumption of innocence principle is not applicable to this paper. Therefore, in Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14, in the BPN forecasting system the prisoners which are predicted to fall into the low recidivism category had the highest actual recidivism rate (33.41%) amongst all forecasting systems. However, with the DANGHS-ANN forecasting system, the prisoners which were predicted to fall into the low recidivism rate category had the lowest actual recidivism rate (31.82%).

According to the above experimental results, the DANGHS-ANN system was the most accurate in comparison with BPN and the four other HS-related ANN forecasting systems used for the prediction of recidivism rates of commuted prisoners.

4. Conclusions and Future Research

We presented a combined DANGHS-ANN forecasting system. Extensive experiments and comparisons were carried out to solve the problem of accurately predicting recidivism rates for commuted prisoners. The experimental results provide several findings that are worth noting.

Firstly, using the threshold linear posterior decreasing strategy with the DANGHS-ANN forecasting system yielded the best results for recidivism prediction. Additionally, according to the p-value and convergence graph, DANGHS-ANN outperformed the five other forecasting systems (BPN, HS-ANN, IHS-ANN, SGHS-ANN, and NGHS-ANN).

Secondly, it was found that using metaheuristic-ANN with the dynamic parameter adjustment strategy, such as DANGHS-ANN and IHS-ANN, could result in improved forecasting performance as opposed to using systems without the dynamic parameter adjustment strategy, such as NGHS and the HS. In other words, using a parameter adjustment strategy improves the prediction ability of the NGHS-ANN forecasting system. This conclusion is aligned with the study by Chiu et al. [17].

Finally, by comparing and analyzing actual versus predicted recidivism, it is shown that the DANGHS-ANN model proposed in this paper could reduce the number of prisoners with a high recidivism rate being granted commutation or parole. Thereby, the proposed forecasting system could reduce the occurrence of recidivism and improve the public’s opinion of the commutation and parole policy. In conclusion, DANGHS-ANN is the more accurate and acceptable forecasting system.

It is worth noting that we still have many factors that have not been considered in this paper. Thus, we could further explore these factors in the future. First, we investigated the performance of proposed forecasting system DANGHS-ANN in the fixed structure of MLP. In the future, we could investigate the robustness of the DANGHS-ANN in different structures of MLP or in the input data sets with noise. Second, in this paper, we used BPN and several HS-ANNs to forecast the recidivism rate. However, there are many metaheuristic algorithms and forecasting methods, such as differential evolution (DE), PSO, AR, SVM, etc. In the future, we could use different artificial intelligence methods to solve this problem. Third, we investigated the performance of the dynamic adjusting parameter mechanism in the DANGHS algorithm only. In the future, we could investigate the performance of combining different dynamic adjusting parameter mechanisms into other metaheuristic algorithms, such as teaching learning based optimization (TLBO) [38], modified coyote optimization algorithm (MCOA) [39], Harris hawks optimization (HHO) [40], etc.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.-C.S. and C.-Y.C.; methodology, P.-C.S.; software, P.-C.S.; validation, P.-C.S.; formal analysis, P.-C.S.; resources, C.-H.C.; data curation, C.-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.-C.S.; writing—review and editing, P.-C.S.; visualization, P.-C.S.; supervision, C.-Y.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the reviewers for their constructive comments and Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| ACO | ant colony optimization |

| ANN | artificial neural network |

| AR | association rule |

| BP | backpropagation |

| BPN | backpropagation network |

| BW | bandwidth |

| coefficient of cycle | |

| DANGHS | dynamic adjusting novel global harmony search |

| DE | differential evolution |

| EWR | example-to-weight ratio |

| GA | genetic algorithm |

| HHO | Harris hawks optimization |

| HM | harmony memory |

| HMCR | harmony memory considering rate |

| HS | harmony search |

| IGHS | intelligent global harmony search |

| IHS | improved harmony search |

| current iteration | |

| K | K-fold cross validation |

| LP | learning period |

| m | harmony memory size |

| MCOA | modified coyote optimization algorithm |

| MLP | multilayer perceptron |

| MSE | mean squared error |

| n | total number of experiments |

| NGHS | novel global harmony search |

| NHN | number of hidden neurons |

| NI | maximum number of iterations |

| number of input neurons | |

| number of output neurons | |

| PAR | pitch adjusting rate |

| genetic mutation probability | |

| PSO | particle swarm optimization |

| SGHS | self-adaptive global best harmony search |

| SVM | support vector machine |

| TLBO | teaching learning based optimization |

References

- Carroll, J.S.; Wiener, R.L.; Coates, D.; Galegher, J.; Alibrio, J.J. Evaluation, Diagnosis and Prediction in Parole Decision Making. Law Soc. Rev. 1982, 17, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.P.; McShane, M.D.; Dolny, H.M. Predicting Parole Absconders. Prison J. 2000, 80, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, D.L.; Spencer, D.L. The Impact of Formal & Social Controls on the Criminal Activities of Probationers. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2002, 39, 243–276. [Google Scholar]

- Benda, B.B. Survival Analysis of Criminal Recidivism of Boot Camp Graduates Using Elements From General & Developmental Explanatory Models. Int. J. Offender Ther. 2003, 47, 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Trulson, C.R.; Marquart, J.W.; Mullings, J.L.; Caeti, T.J. In Between Adolescence and Adulthood: Recidivism Outcomes of a Cohort of State Delinquents. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2005, 3, 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-I.; Jung, H.-S. Automatic Ship Detection Using the Artificial Neural Network and Support Vector Machine from X-Band Sar Satellite Images. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemitzi, A.; Lakshmi, V. Estimating Groundwater Abstractions at the Aquifer Scale Using GRACE Observations. Geosci. J. 2018, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-L.; Tien, F.-C. Reclaim wafer defect classification using SVM. In Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Industrial Engineering & Management Systems Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–10 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moodley, R.; Chiclana, F.; Caraffini, F.; Carter, J. A product-centric data mining algorithm for targeted promotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 3, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, F.-C.; Sun, T.-H.; Liu, M.-L. Reclaim Wafer Defect Classification Using Backpropagation Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Recent Development in Engineering and Technology, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–24 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, S.; Valian, E.; Mohanna, S. Feedforward neural network training using intelligent global harmony search. Evol. Syst. 2012, 3, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-J.; Gupta, K.C.; Devabhaktuni, V.K. Artificial Neural Networks for RF and Microwave Design—From Theory to Practice. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Thch. 2003, 51, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, I.A.; Hajmeer, M. Artificial neural networks: Fundamentals, computing, design, and application. J. Microbiol. Methods 2000, 43, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattan, A.; Abdullah, R. Training of feed-forward neural networks for pattern-classification applications using music inspired algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2011, 9, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran, J.; Ravi, G. Long-term Sector-wise Electrical Energy Forecasting Using Artificial Neural Network and Biogeography-based Optimization. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2015, 43, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göçken, M.; Özçalıcı, M.; Boru, A.; Dosdogru, A.T. Integrating metaheuristics and Artificial Neural Networks for improved stock price prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 44, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-Y.; Shih, P.-C.; Li, X. A Dynamic Adjusting Novel Global Harmony Search for Continuous Optimization Problems. Symmetry 2018, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Gao, L.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. A novel global harmony search algorithm for task assignment problem. J. Syst. Softw. 2010, 83, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Gao, L.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Li, Y. A novel global harmony search algorithm for reliability problems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2010, 58, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Gao, L.; Wu, J.; Li, S. Novel global harmony search algorithm for unconstrained problems. Neurocomputing 2010, 73, 3308–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.K.; Suganthan, P.N.; Tasgetiren, M.F.; Liang, J.J. A self-adaptive global best harmony search algorithm for continuous optimization problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2010, 216, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valian, E.; Tavakoli, S.; Mohanna, S. An intelligent global harmony search approach to continuous optimization problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 232, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W.; Kim, J.H.; Loganathan, G.V. A new heuristic optimization algorithm: Harmony search. Simulation 2001, 76, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, M.G.H.; Mahdavi, M. Global-best harmony search. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 198, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Fesanghary, M.; Damangir, E. An improved harmony search algorithm for solving optimization problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 188, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 4–6 October 1995; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.H.; Chen, L.F.; Su, C.T. A new particle swarm feature selection method for classification. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2014, 42, 507–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Vuković, N.; Mitić, M.; Miljković, Z. Integration of process planning and scheduling using chaotic particle swarm optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 64, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, N.; Hemayed, E.E.; Fayek, M.B. A GA-based approach for epipolar geometry estimation. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2013, 27, 1355014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metawaa, N.; Hassana, M.K.; Elhoseny, M. Genetic algorithm based model for optimizing bank lending decisions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 80, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S. Design of distributed database systems: An iterative genetic algorithm. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2015, 45, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, T. Practical Neural Network Recipes in C++; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780124790407. [Google Scholar]

- Looney, C.G. Advances in feedforward neural networks: Demystifying knowledge acquiring black boxes. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 1996, 8, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowla, F.U.; Rogers, L.L. Solving Problems in Environmental Engineering and Geosciences with Artificial Neural Networks; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0262515726. [Google Scholar]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0023527617. [Google Scholar]

- Zupan, J.; Gasteiger, J. Neural Networks for Chemists: An Introduction; VCH: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 3527286039. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, R.V.; Savsani, V.J.; Vakharia, D.P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput. Aided Des. 2011, 43, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cao, Y.; Dai, L.V.; Yang, X.; Nguyen, T.T. Optimal Power Flow for Transmission Power Networks Using a Novel Metaheuristic Algorithm. Energies 2019, 12, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).