4.1. Experimental Configuration and Characteristics

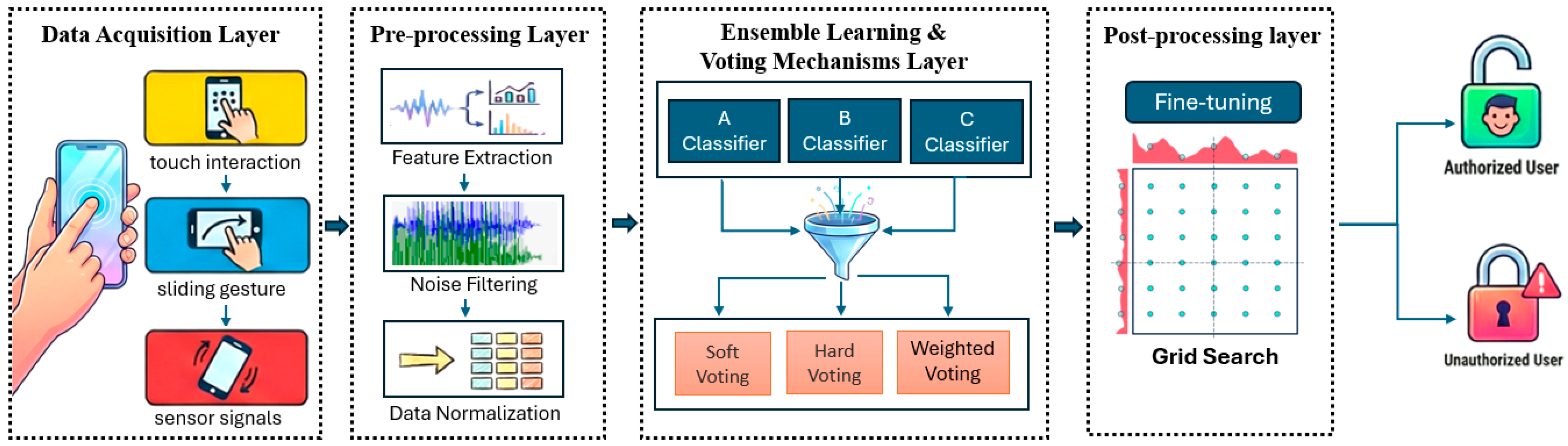

To facilitate experimental reproducibility and ensure the ecological validity of the behavioral dataset, the acquisition was standardized as shown in

Table 3. Data collection was performed using the OPPO A3 Pro smartphone equipped with a MediaTek Dimensity 7050 processor running Android 14. This device served as the edge computing node for capturing high-fidelity telemetry. The study involved 15 participants (10 males, 5 females) to ensure gender diversity in behavioral patterns. The data collection pipeline consisted of three synchronized phases: touch (keystroke dynamics), sliding (geometric trajectory analysis), and sensor signals (IMU sensor fusion). Each data collection session comprised three distinct phases: (1) a numeric keypad interaction requiring discrete taps on specific digits, (2) a trajectory tracing task where users were prompted to follow a geometric template, and (3) a device kinematic task involving physical orientation shifts (tilting the device left or right). This comprehensive sequence was performed over four consecutive rounds, with the first and second rounds utilizing a circular template, while the third and fourth rounds employed a square template to capture variations in motor control across different geometric constraints.

To ensure rigorous evaluation, we implemented a user-dependent, round-based 4-fold cross-validation strategy. Data were partitioned by acquisition phase—using three rounds for training and one for testing—rather than random shuffling. This approach enforces strict temporal isolation, preventing intra-session data leakage while assessing resilience to behavioral drift. Additionally, limitations regarding the cohort size (N = 15) and its impact on generalizability are explicitly acknowledged.

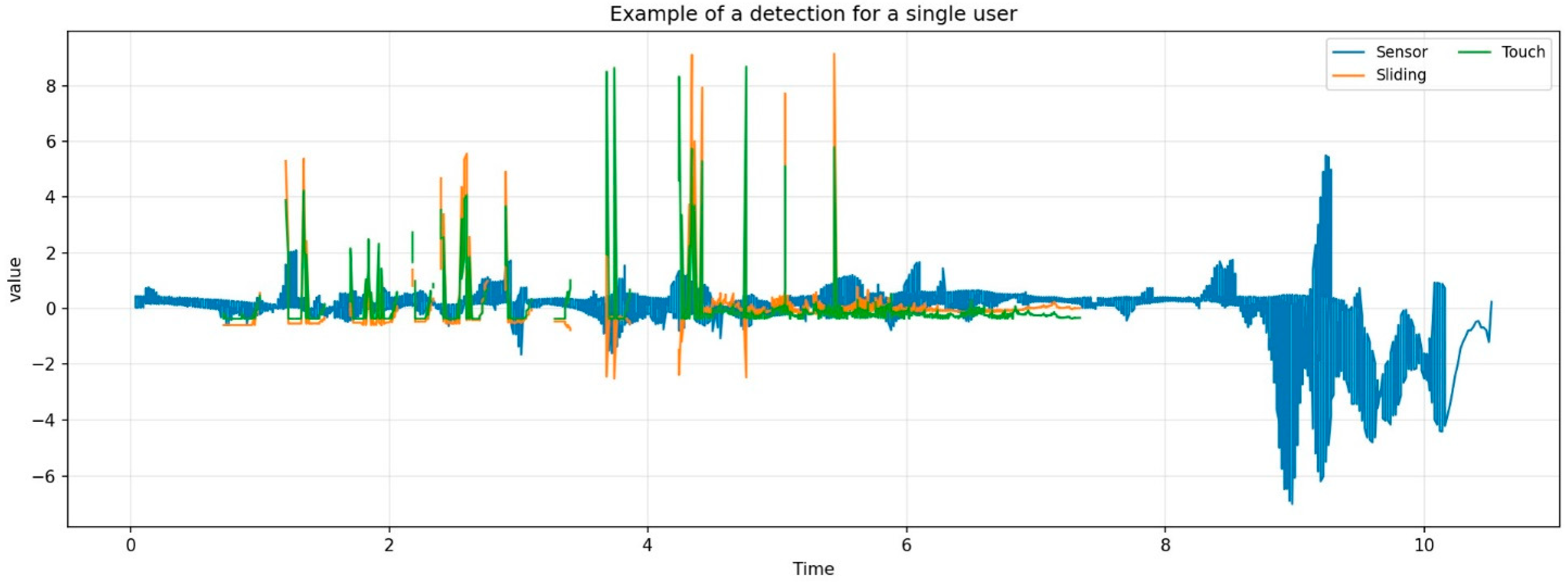

The total dataset comprises 35,519 samples. To simulate realistic zero-trust attack scenarios where unauthorized access attempts significantly outnumber authorized operations, the dataset maintains a strict class imbalance. It contains 1984 positive samples (Target User) and 33,535 negative samples (Unauthorized/Others). A stratified sampling method was employed to divide the dataset into training and testing sets with an 80:20 ratio, ensuring that the temporal integrity of the behavioral sessions was preserved. The temporal fluctuations and signal densities of the three behavioral modalities are illustrated in

Figure 2, providing critical insights into the data acquisition layer’s performance. Visualization reveals a fundamental distinction between the continuous nature of inertial sensors and the event-driven sparsity of interactive gestures. The persistent availability of sensor signals serves as a foundational edge computing node for continuous authentication, ensuring that the authentication framework maintains an uninterrupted security posture across diverse mobile usage scenarios.

4.2. Performance Evaluation of the Optimized Heterogeneous Ensemble

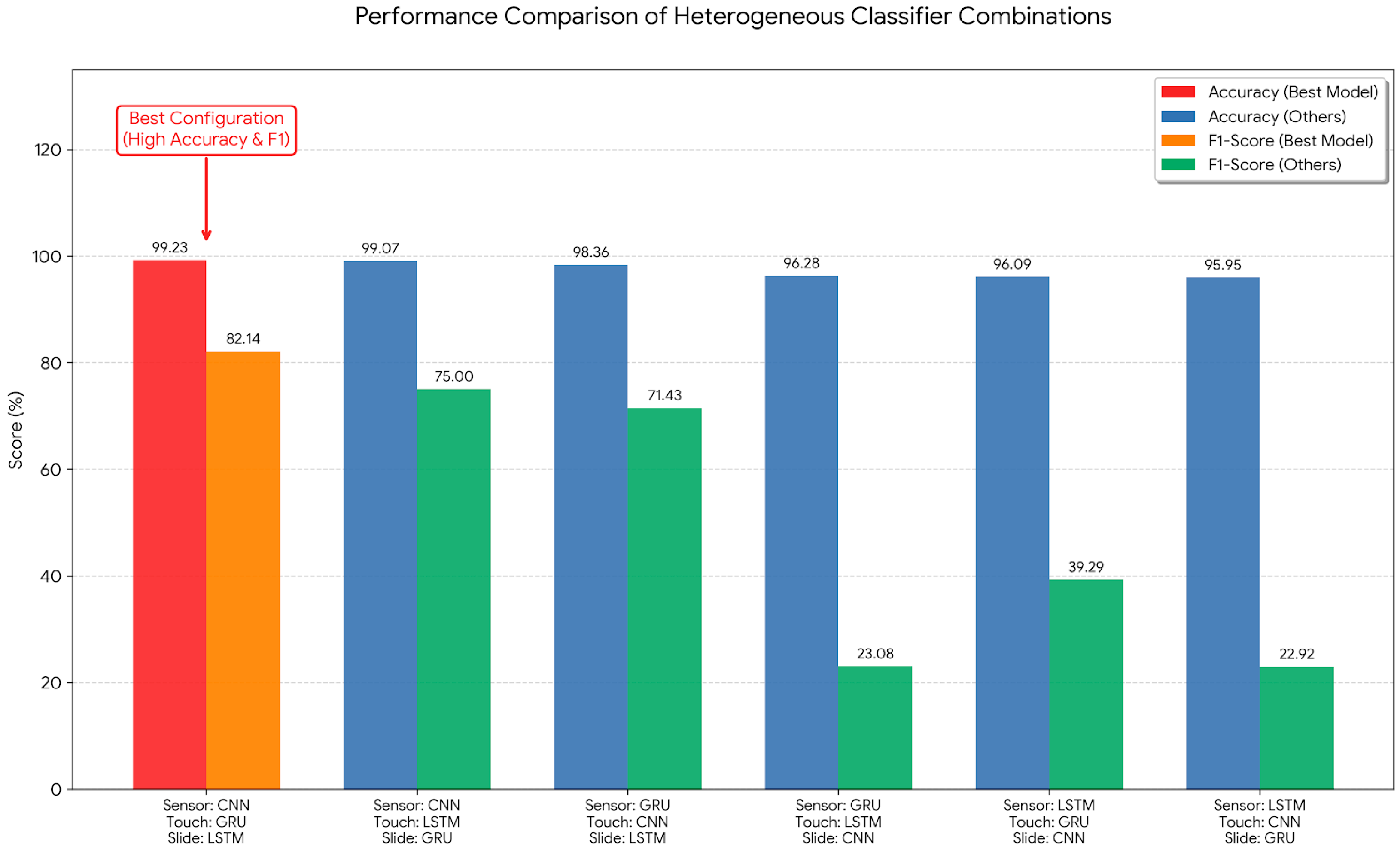

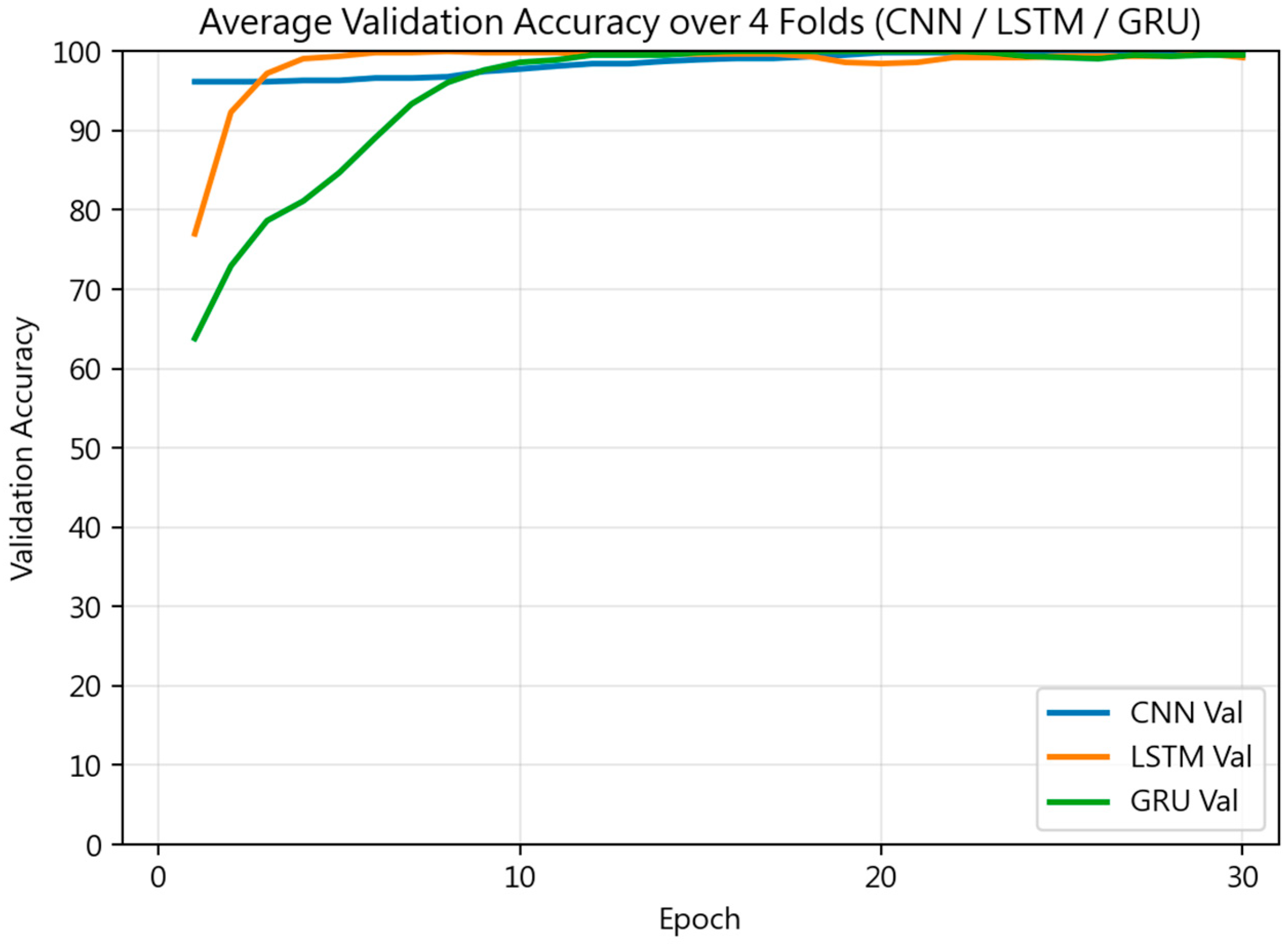

To validate the hypothesis that distinct behavioral modalities require specialized neural topologies, we evaluated the performance of six permutations of CNNs, GRUs, and LSTMs across three data streams: touch, sliding, and sensor signals. The performance metrics of the heterogeneous classifier architectures are illustrated in

Figure 3. The configuration employing CNNs for sensor data, GRUs for touch input, and LSTMs for sliding achieves the highest accuracy and F1-score, confirming the necessity of modality-specific architectural alignment. This architecture attains a peak accuracy of 99.23% and an F1-score of 82.14%. This performance hierarchy can be attributed to the intrinsic properties of each neural architecture. CNNs demonstrate superior capability in modeling high-frequency inertial signals, providing a stable baseline. GRUs are computationally efficient and effectively capture the short-term, sparse characteristics of touch tap events. LSTMs excel at modeling longer-term temporal dependencies inherent in continuous sliding. In contrast, architectures that misalign models with modalities (e.g., using LSTMs for sensor data, CNNs for touch, and GRUs for sliding) suffer significant performance degradation, with F1-scores dropping to as low as 22.92%. These results confirm that a specialized model approach is insufficient for multimodal behavioral biometrics.

A critical challenge in continuous authentication systems is the inherent class imbalance between authorized users and impostor attempts. In this study, the dataset exhibits a significant imbalance ratio of approximately 1:17. Under such conditions, standard voting mechanisms using default decision thresholds (e.g., = 0.5) often yield misleadingly high accuracy by biasing predictions toward the majority negative class. This results in a low True Positive Rate (Recall), rendering the system ineffective for genuine user verification.

To mitigate this, we implemented a systematic GSO strategy to optimize the hyper-parameters, specifically the weight vectors and decision thresholds across hard, soft, and weighted voting architectures.

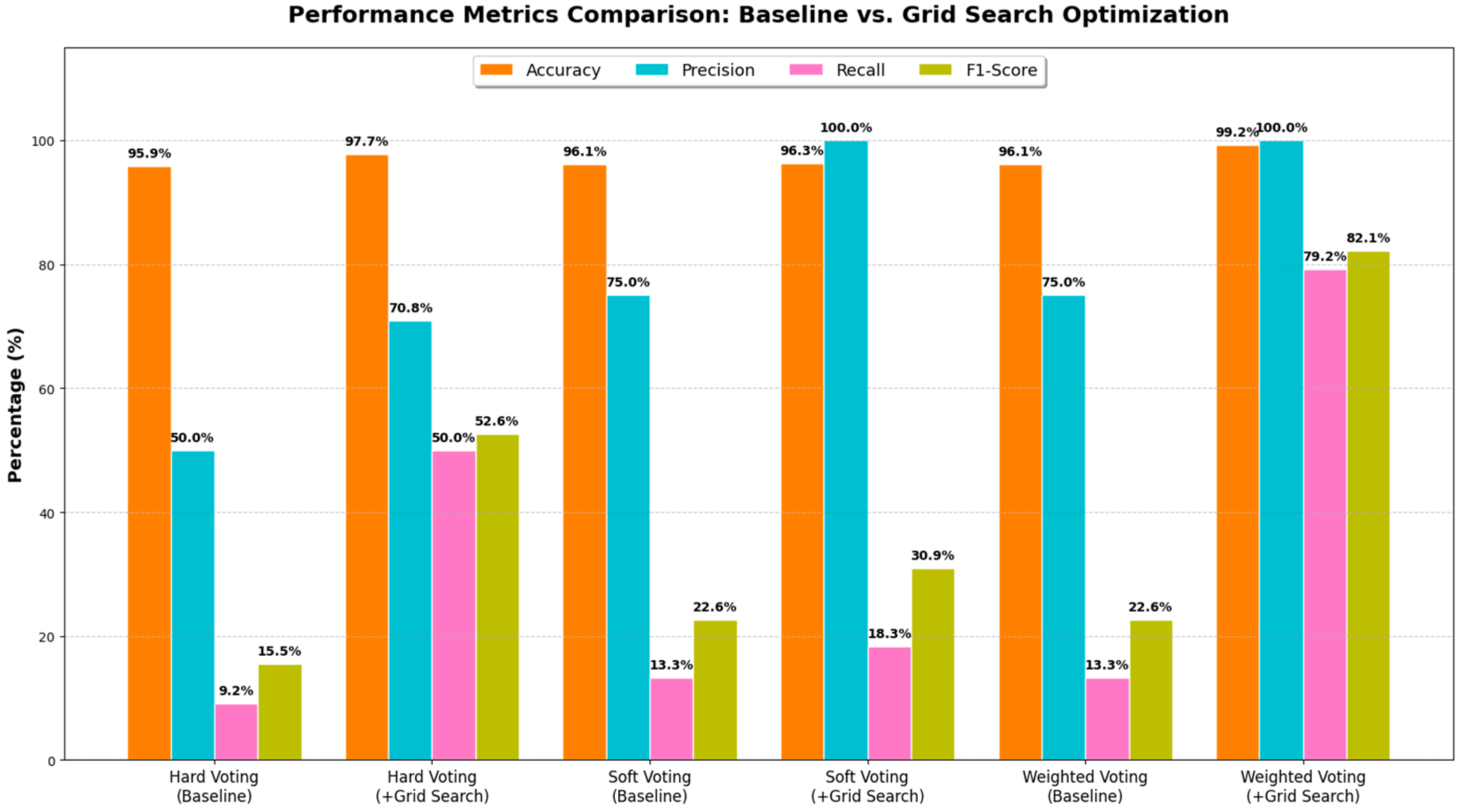

Table 4 details the performance metrics for each mechanism before and after optimization. In the baseline configuration, all three voting methods exhibited poor sensitivity to the authorized user class. As shown in

Table 4, while the baseline hard voting achieved an accuracy of 95.87%, its F1-score was limited to 15.48% due to a critical recall of only 9.17%. Similarly, soft voting and weighted voting produced identical baseline results with an F1-score of 22.62%, indicating that without calibration, the ensemble classifiers failed to effectively distinguish the minority class from the noise of the majority class.

Figure 4 shows the performance comparison of the substantial impact of GSO strategy, particularly on the weighted voting scheme, which demonstrates the most robust balance between precision and recall. These results confirm that a modality-specific model voting strategy is insufficient for behavioral biometrics. The optimized weighted voting mechanism successfully establishes a precise decision boundary that maximizes the detection of authorized users while maintaining zero false acceptances, thereby satisfying the stringent security requirements of the Zero Trust framework.

Table 5 provides a comprehensive performance benchmark, contrasting the singular modalities, CNNs, GRUs, and LSTM against the proposed method that integrates these heterogeneous topologies via a Grid Search-optimized weighted voting scheme. The data indicates that the standalone CNNs exhibit a respectable accuracy of 92.85% by effectively capturing spatial patterns in high-frequency sensor, yet it remains hindered by a relatively low precision of 55.26%, suggesting a propensity for false positives in complex usage scenarios. Similarly, although the GRUs architecture achieves a baseline accuracy of 97.29%, its recall remains capped at 58.33%, demonstrating an inability to resolve the subtle temporal dependencies required for robust identity verification across diverse interaction types.

Empirical results indicate that GSO yielded divergent performance enhancements across the evaluated voting architectures. Hard voting saw a substantial improvement, with its F1-score increasing to 52.60%. Conversely, soft voting demonstrated limited plasticity; despite achieving perfect precision (100.00%), its Recall remained low at 18.33%, resulting in a modest F1-score of 30.95%. This suggests that soft voting, which relies on averaging probability distributions, struggles to resolve confidence ambiguities in highly imbalanced data. The most significant performance gain was observed in the weighted voting mechanism. This approach dynamically assigned optimal weights to the most reliable modalities, particularly sensor data. After fine-tuning the decision threshold, it achieved a peak accuracy of 99.23%. More importantly, it attained a precision of 100.00% and a recall of 79.17%, pushing the F1-score to 82.14%.

To ensure rigorous validation, training and testing sliding windows were kept strictly disjoint, originating from distinct temporal sessions. This design effectively evaluates robustness against intra-subject behavioral drift, mirroring the operational demands of continuous authentication. Regarding the optimization objective, the empirical results in

Table 4 validate the necessity of prioritizing the F1-score over accuracy. Given the severe class imbalance, standard voting mechanisms succumbed to the “Accuracy Paradox,” yielding F1-scores below 23%. In contrast, by shifting the GSO objective to the F1-score, the Weighted Voting mechanism achieved a substantial performance increase to 82.14%. This confirms that decision-level optimization targeting the F1-score is critical for correcting majority-class bias.

The proposed method fundamentally overcomes these constraints by aligning modality-specific data structures with the most appropriate neural inductive biases, assigning CNNs to sensor streams, GRUs to discrete touch events, and LSTM to curvilinear sliding. This architectural synergy, further refined by the systematic optimization of decision thresholds and voting weights, yields a peak accuracy of 99.23% and establishes a near-perfect precision of 100.00%. As visualized in the performance comparison chart, the proposed framework achieves a statistically significant escalation in the F1-score, rising from the 50–55% range seen in standalone models to 82.14%. Furthermore, the reduction in Equal Error Rate (EER) to 0.0016 ± 0.0032 underscores the framework’s efficacy in maintaining a precise decision boundary within the Zero Trust paradigm, ensuring that non-intrusive authentication does not compromise system integrity.

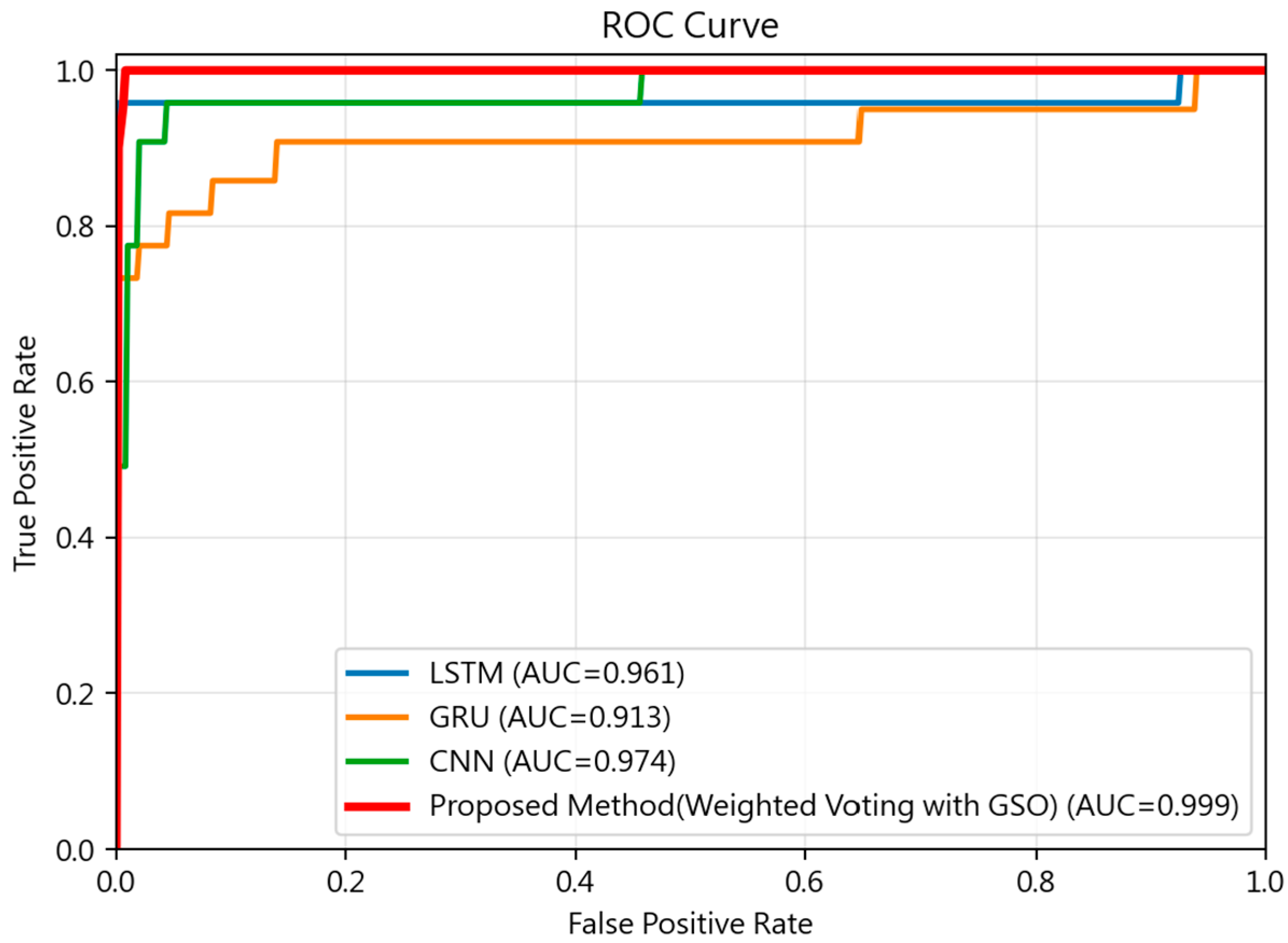

To further evaluate the diagnostic capability and robustness of the proposed framework,

Figure 5 presents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for the individual base classifiers (CNN, LSTM, and GRU) compared against the optimized weighted ensemble. The ROC analysis provides a comprehensive visualization of the performance trade-off between the True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) across varying decision thresholds. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the proposed method achieves a near-ideal Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.999, which significantly exceeds the performance of the standalone CNN (AUC = 0.974), LSTM (AUC = 0.961), and GRU (AUC = 0.913) architectures. This superior discriminative power demonstrates that the GSO strategy effectively aligns the multimodal feature spaces to establish a precise decision boundary. Specifically, the proposed ensemble maintains a high TPR even at extremely low FPR levels—a critical requirement for maintaining a rigorous security posture within ZTA environments without compromising user experience.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Temporal Granularity

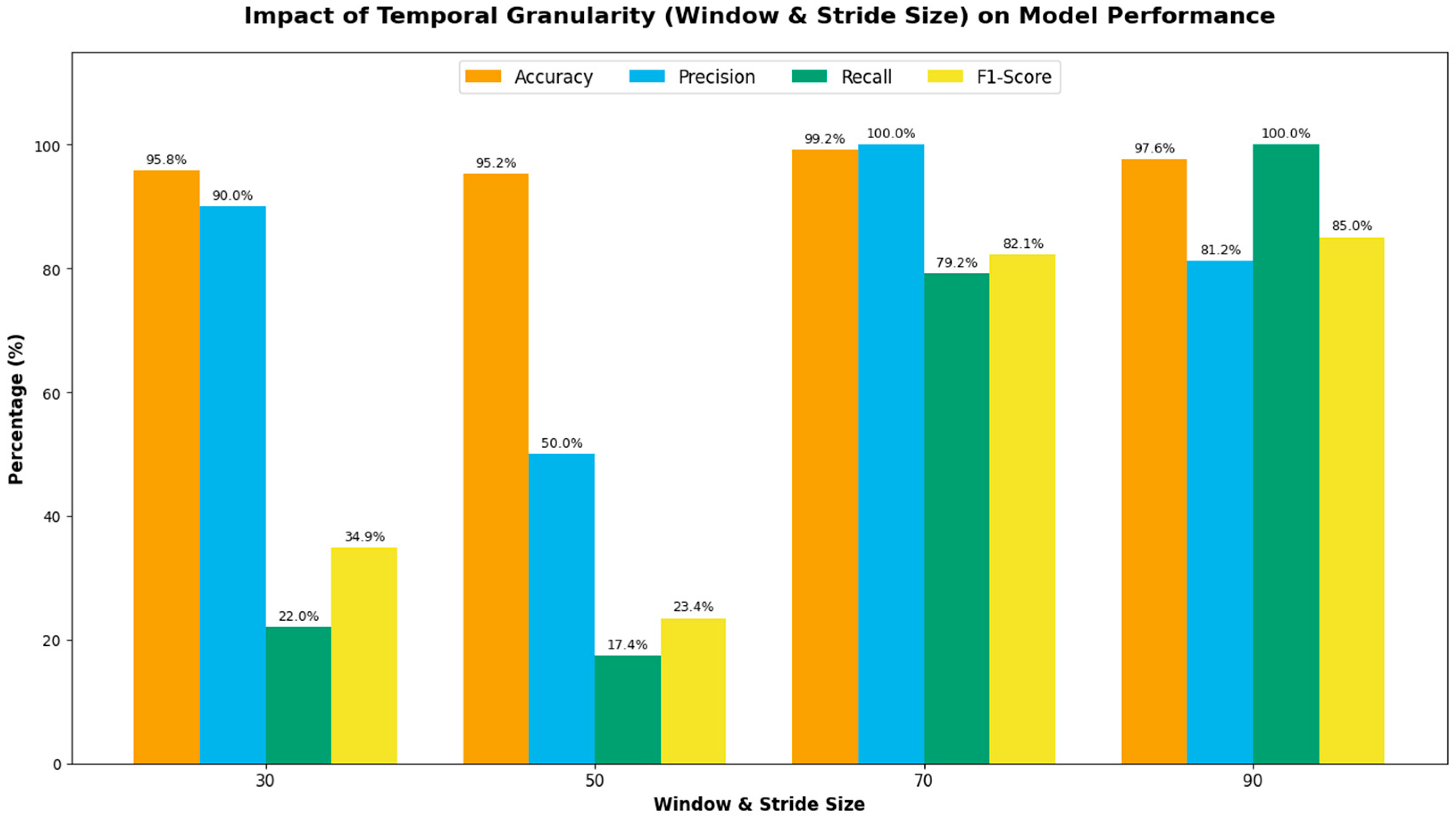

In continuous authentication systems processing time series data, the selection of temporal parameters, specifically window size and stride size is critical. The window size dictates the amount of historical context captured in each input sequence, while the stride size determines the temporal overlap between consecutive sequences. These parameters directly influence the model’s ability to capture latent behavioral patterns and its computational efficiency. In this study, to maintain temporal consistency and avoid data leakage between training and testing sets, the window size was set equal to the stride size. A series of experiments were conducted to evaluate the impact of varying these temporal parameters on the system’s performance.

Table 6 presents the performance metrics obtained for window and stride sizes of 30, 50, 70, and 90 data points.

As detailed in

Table 6 and visualized in

Figure 6, an optimal balance between security and stability was identified at a window and stride size of 70. At this setting, the system achieved the highest accuracy (99.23%) and perfect precision (100.00%), resulting in a robust F1-score of 82.14%. At smaller granularities (W, S = 30 or 50), the models exhibited significantly lower recall (21.96% and 17.37%, respectively) and F1-scores (34.86% and 23.43%). The data suggests that lower temporal granularities fail to capture sufficient latent behavioral context, resulting in elevated false rejection rates. Conversely, increasing the granularity to 90 achieved perfect recall (100.00%) but at the cost of reduced precision (81.25%) and accuracy (97.60%). The decline in precision indicates that excessively large windows may incorporate redundant or noisy data points that degrade the distinctiveness of the user’s behavioral patterns. Consequently, size 70 was established as the optimal operating point for the proposed framework.

While the proposed framework achieves near-perfect precision (>99%), these results should be interpreted within the context of a user-dependent authentication model. Unlike user-independent systems that must generalize across a broad population, our model learns distinctive behavioral signatures for each individual. Furthermore, the multimodal fusion of touch and inertial features significantly reduces ambiguity compared to unimodal approaches. The consistent performance observed across the strict temporal separation of the 4-fold cross-validation further supports the reliability of these results, minimizing the likelihood of overfitting.

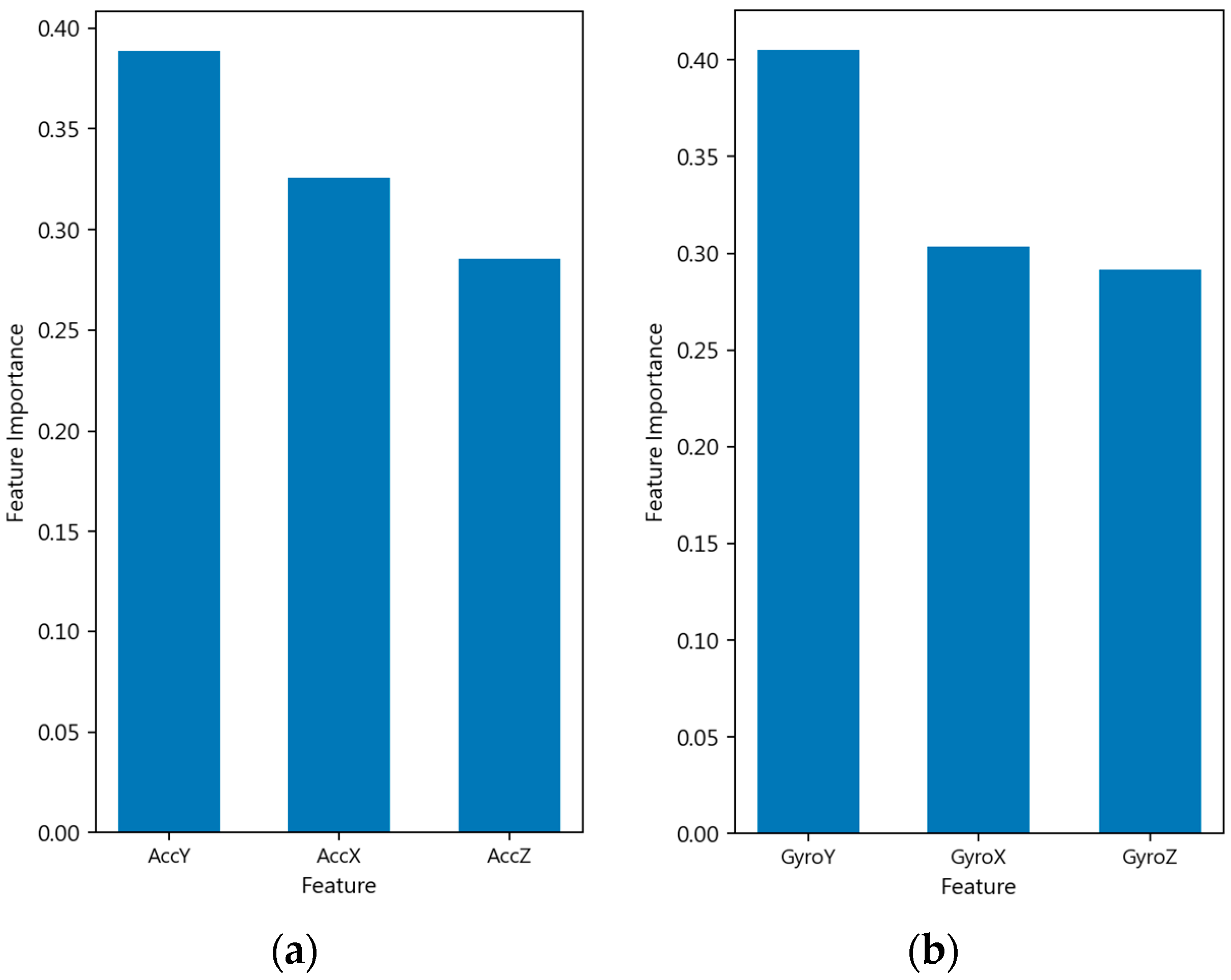

4.5. Interpretability of Kinematic Feature and Trajectory Analysis

To interpret the model’s decision logic, we conducted a feature importance analysis using random forest. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the angular velocity features derived from the Gyroscope dominate the decision boundary. Specifically, GyroY, GyroX, and GyroZ occupy the top rankings with important scores exceeding 0.29. This distribution indicates that the dynamic rotation and orientation changes in the device during usage constitute the primary biometric signature, surpassing linear acceleration features (AccY, AccX, AccZ). While sliding and touch features exhibit lower individual importance scores, they provide essential context-aware cues that complement the continuous sensor.

To evaluate the discriminative power of complex gestural patterns, the experiment incorporated a multi-stage interaction sequence. The experimental results, summarized in

Table 9 reveal that circular trajectories achieved slightly higher classification accuracy (98.46%) compared to square trajectories (98.10%). From a kinematic perspective, circular motion is characterized by higher continuity and smoothness, which leads to more consistent feature representations across different sessions for the same user. In contrast, square trajectories induce significant behavioral variance. The requirement to navigate sharp corners and 90-degree directional changes typically results in momentary deceleration followed by a rapid change in angular velocity. These “corner-turning” kinematics are often executed with less consistency by the same individual across multiple attempts, introducing intra-class noise that complicates the classification boundary. Despite this increased complexity, the square gestures achieved a marginally higher F1-score (66.67%) compared to circular gestures (64.29%), suggesting that the sharp kinematic transitions provide unique anchors for identity verification even if they are more difficult to model precisely.

Despite the framework’s efficacy, three limitations persist. First, the cohort size (N = 15) may constrain generalizability across diverse demographics. Second, controlled data acquisition likely establishes performance upper bounds by omitting “in-the-wild” variables such as locomotion artifacts. Finally, reliance on a single device model introduces hardware dependencies, necessitating future validation across heterogeneous IMU sensitivities to address potential domain shifts.