The numerator polynomial consists of polynomial terms of Cartesian coordinates multiplied by their respective coefficients:

where

denotes the set of valid exponent triplets. The algorithm is designed to numerically determine, for each polynomial term, both the exponent triplet

of the Cartesian monomials

and their corresponding coefficients

.

3.2.1. Exponent Triplet Generation

The set

(from Equation (

12)) of all valid exponent triplets

is strictly determined by two fundamental mathematical constraints: homogeneity and parity constraints.

1. Constraint: Homogeneity

The function, , is a homogeneous function of degree . The partial differential operators , , and are, themselves, homogeneous operators of degree .

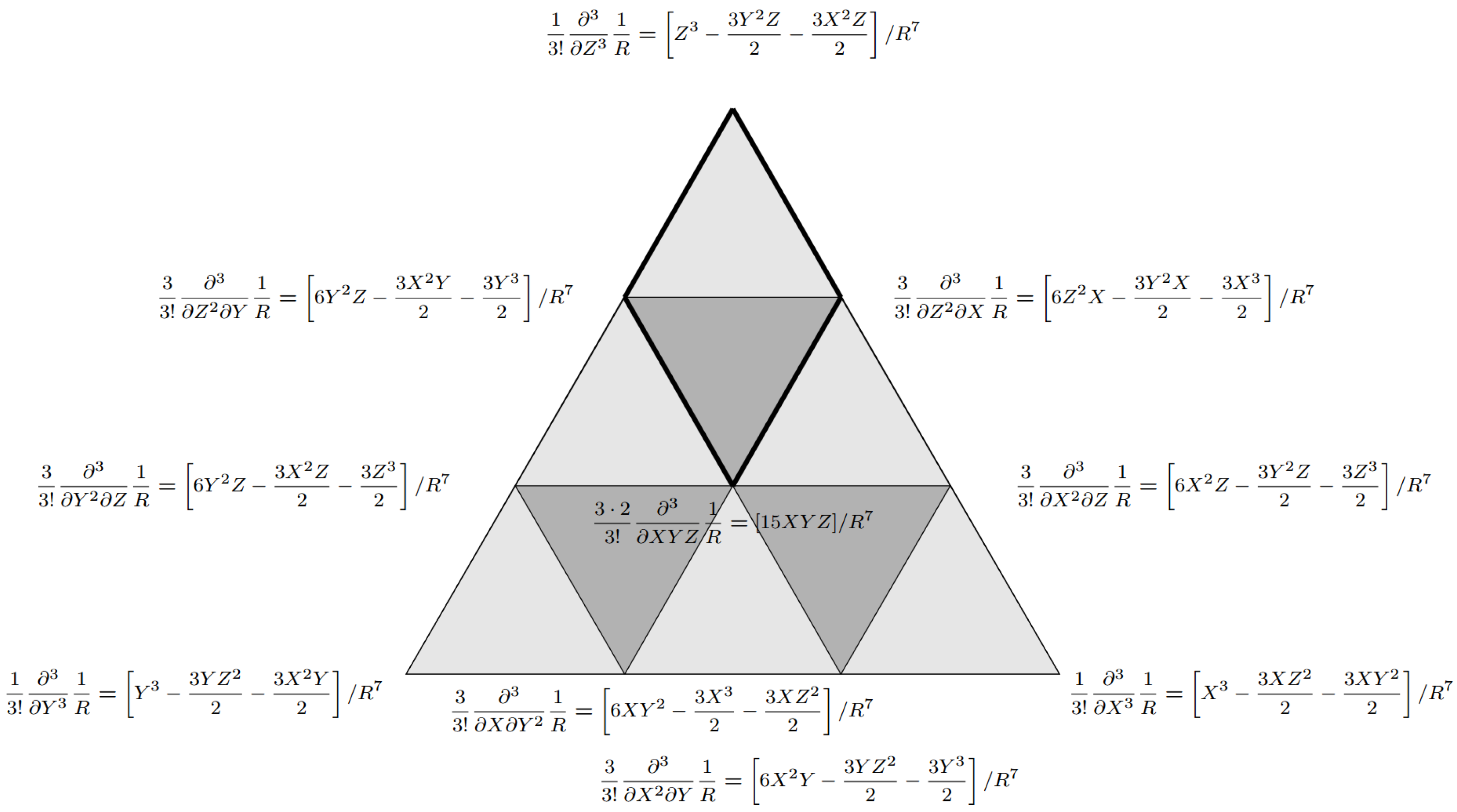

It follows that the n-th order partial derivative is a homogeneous function of degree . Given that the denominator of the expression, , is a homogeneous function of degree , the numerator polynomial must necessarily be a homogeneous polynomial of degree n, such that the total degree of the fraction is .

The condition of homogeneity implies that for every term in the polynomial

, the sum of the exponents must be exactly

n. Therefore, for every element

of the set of exponents, the following must hold:

where

2. Constraint: Parity

The function is an even function with respect to all three coordinates (), as , , and .

The operation of partial differentiation alters the parity of a function:

Consider the operator . When applied to the function:

If l is even, the parity of the resulting function with respect to X remains even.

If l is odd, the parity of the resulting function with respect to X becomes odd.

In general, the parity of the complete function with respect to X must be the same as the parity of l; its parity with respect to Y must be the same as ; and its parity with respect to Z must be the same as .

As the denominator, is also an even function with respect to all three variables; this parity constraint is inherited directly by the numerator polynomial, .

The parity of a polynomial with respect to X is determined by the parity of its constituent exponents. For to satisfy the parity of l, every term must have an exponent i that has the same parity as l. The same holds true for Y and Z. This second set of constraints can be described by the following:

l and i always have the same parity: if l is even, then i is also even; if l is odd, then i is also odd.

and j always have the same parity: if is even, then j is also even; if is odd, then j is also odd.

and k always have the same parity: if is even, then k is also even; if is odd, then k is also odd.

Number of terms

For a given degree

n, order

m, and index

l, the number of terms satisfying the homogeneity and parity constraints is denoted by

. Based on the combinatorial constraints on the exponents

i and

j, three distinct cases arise:

where

denotes the floor operation (rounding down).

3.2.2. Derivation of the Numerator Polynomial Coefficients

The coefficients of the numerator polynomial are generated using a recursive scheme. Each differentiation step () represents a recursive relation that computes the new coefficients from the previous set.

Definition of the Recursive Realtions

Let

denote the coefficient of the monomial

within the

n-th degree numerator polynomial,

. The coefficients (

or

or

) for the

-th order polynomial,

, are given by the following rules, depending on the variable of differentiation. The proof is presented in

Appendix B.

Recursive computation of the coefficients under partial differentiation with respect to X:

Recursive computation of the coefficients under partial differentiation with respect to Y:

Recursive computation of the coefficients under partial differentiation with respect to Z:

The recursion is anchored by the 0-th-order derivative,

, for which the numerator polynomial is

. This provides the initial condition

, with all other coefficients being zero. Any term in the recurrence relations Equations (

14)–(

16) that references a coefficient with a negative exponent (e.g.,

) is defined as zero.

3.2.3. Analytical Solution for the Z-Derivative

Coefficient of the “principal”

term of the Z-Derivative We examine the coefficient of the “principal” term, which is the term containing only the highest power of Z,

, denoted

. Setting

,

, and

in the Z-Derivative Equation (

16):

The first two terms are zero, as they reference coefficients with negative (invalid) exponents. The third term, the only one to survive, simplifies as follows:

This yields a simple recurrence for the principal coefficient,

:

The given recurrence relation can be transformed into a closed-form expression. Starting from the initial condition

, the recurrence

simplifies to

which leads to

This demonstrates that the coefficient for the

term, represented as

, is

Coefficient of the other terms of the Z-Derivative This analysis can be extended to the other terms of the

Z-derivative, which have the form

where

and

A similar, albeit more complex, recurrence relates the coefficient of these terms. Unwinding this

q-based recurrence, applying the binomial theorem to the

term and substituting

yields the general product formula

For Z-Derivatives: Analytical Simplification

The partial differentiation process is always initiated with respect to the Z coordinate. Consequently, in the base case where

(implying purely zonal harmonics), the binomial weights

and

in Equation (

10) all reduce to unity. The remaining normalization terms are the

and the Schmidt correction factor

, which is

in this case. Since for

,

is identical to

, this term can be directly factored out from the raw coefficient in Equation (

17), allowing for the exact analytical cancellation described above.The algorithm performs this analytical cancellation before any numerical computation. The resulting simplified formula, which is now free of the

growth, is then computed. The final and simplified coefficient for a specific monomial

is:

For X/Y-Derivatives: Step-Wise Normalization

For the recursive branches, the normalization factors (

,

,

, and

) from Equation (

10) are not applied at the end, but are applied at each step of the recursion. The factorial growth generated by the recurrence relations (Equations (

14) and (

15)) is immediately cancelled by applying a corresponding normalization factor (

). This ensures all computed coefficients remain bounded and immune to overflow. The normalization factors are decomposed into their recursive ratios (

) and are integrated directly into each step.

During the step, the coefficient or is computed from the preceding coefficients multiplied by a recursive normalization factor ().

A critical detail in Schmidt semi-normalization is the discontinuity between and . The normalization factor includes a multiplier for all orders , which is absent for . Consequently, the recursive ratio must account for this transition when .

The corrected recursive normalization factor is composed of three components. To achieve full normalization, the correction term (

) is adjusted to account for the

scaling factor inherent in the transition from degree

to

n:

where

n is the new total degree,

m is the new total X/Y order,

l is the X order, and

is the Kronecker delta (which equals 1 if

, introducing the necessary

factor, and 0 otherwise).

The factor

encapsulates the transition from iteration

to

n, derived directly from the coefficients in Equation (

10). It is formulated as a product of three distinct components to maintain numerical precision:

Factorial scaling (

): Originates from the Taylor series expansion (

) found in Equation (

10), counteracting the factorial growth of higher-order derivatives.

Combinatorial weight (): Accounts for the binomial distribution of partial derivatives along the Cartesian axes.

Normalization (): The Schmidt normalization factor () standardizes the magnitude of the harmonics, ensuring consistent physical scaling, and gives the name to the combined coefficient.

Numerical Note: If the factorial and normalization terms were applied globally after computing the raw high-order derivatives of , the calculation would fail due to arithmetic underflow (vanishing derivatives) and overflow (huge factorials). By applying these factors incrementally within each recursive step via , the intrinsic decay of the derivatives is continuously balanced by the factorial term (), while the Schmidt component () enforces the physical normalization, keeping the intermediate coefficients within a stable numerical range (∼1.0).

(Differentiation with respect to X)

Substituting into the general form and merging the square roots for simplicity:

(Differentiation with respect to Y)

Similarly for the Y-derivative (where the binomial term results in a factor of

):

By incorporating these recursive factors, the complete, numerically stable form of the recurrence relations is as follows:

The Normalized Recurrence Relations

Normalized recursive computation of the coefficients under partial differentiation with respect to X

Normalized recursive computation of the coefficients under partial differentiation with respect to Y

This normalization method ensures numerical stability by avoiding the ill-conditioned multiplication of terms with an extreme dynamic range. It transforms the operation from a post-process multiplication (involving factorially large terms and infinitesimally small factors) into a sequential process where all intermediate values are kept near unity. This approach not only prevents numerical overflow but also inherently minimizes the propagation of compounding round-off errors.