1. Introduction

The development of next-generation mobile systems, particularly sixth-generation (6G) communications, is recognized as an important global objective. Extensive research efforts continue to address the performance demands of future wireless networks [

1,

2]. Mobile communications have rapidly advanced during the past decade and now form a fundamental infrastructure for society and industry. According to the Ericsson Mobility Report [

3], mobile data traffic increased more than fifteen-fold from 2017 to 2022 and the number of mobile subscriptions is expected to reach approximately 4.4 billion by the end of 2027.

The rapid growth of traffic and the rising requirements for quality of service (QoS) highlight the need for multiple access schemes that improve both spectral and energy efficiency. Conventional orthogonal multiple access (OMA) assigns wireless resources in orthogonal time or frequency domains. OMA is simple and experiences limited interference, but its strict orthogonality reduces spectral efficiency and limits the achievable data rates of users, particularly those at the cell edge [

4,

5]. As a result, OMA is not sufficient for supporting the massive connectivity and high data rate demands of future networks.

To overcome these limitations, multi-antenna technologies such as multiple input multiple output (MIMO) were introduced in 4G and 5G systems. These techniques enable spatial division multiple access (SDMA) [

6]. SDMA uses spatial resources and multi-antenna processing at the transmitter to serve multiple users at the same time on the same frequency resources. Each user decodes its signal by treating residual interference as noise.

Multiple access schemes have also evolved toward non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) to improve spectral efficiency. NOMA allows multiple users to share the same resource block and relies on successive interference cancellation (SIC) at the receiver [

4]. However, its multi-layer SIC structure makes the scheme highly vulnerable to error propagation, and the dependence on accurate channel state information (CSI) becomes more severe as the number of layers increases. These limitations reduce the robustness of NOMA in practical wireless environments. Even in multiple-input-single-output (MISO) networks, the channel strength alone is not sufficient for user separation, which makes it difficult for NOMA to achieve the theoretical capacity [

5].

In the context of 6G communications, multiple access schemes are required not only to achieve high spectral efficiency, but also to provide robustness, flexibility, and reliable QoS support under heterogeneous user demands and imperfect channel conditions. Compared to power-domain NOMA, which relies heavily on accurate SIC ordering and is vulnerable to error propagation, rate-splitting multiple access (RSMA) offers a more flexible interference management mechanism by splitting messages into common and private streams and combining this with MIMO-based linear precoding. This structure allows RSMA to partially decode interference when beneficial and treat residual interference as noise otherwise, effectively bridging the extremes of SDMA and NOMA. As a result, RSMA is inherently more robust to imperfect CSI, receiver limitations, and heterogeneous QoS requirements, which are key challenges anticipated in 6G networks. A concise comparison between power-domain NOMA and RSMA is summarized in

Table 1.

Motivated by these requirements, RSMA has gained significant attention as a promising approach for 6G and beyond. RSMA divides each user message into a common stream and a private stream and combines this with MIMO-based linear precoding [

5]. Because of these advantages, RSMA has been studied in a variety of scenarios, including OFDM systems [

7], adaptive power allocation [

8], unmanned aerial vehicle communications [

9], full-duplex transmission [

10], and heterogeneous networks [

11]. However, despite its strong theoretical performance, the practical implementation of RSMA requires solving complex resource allocation problems, particularly the joint optimization of power allocation, precoder design, user scheduling, and subcarrier assignment, which remains highly challenging in practice.

Most existing studies address these challenges through instantaneous optimization, focusing on per-slot performance under instantaneous CSI, and do not explicitly account for long-term QoS guarantees. To cope with these challenges, several studies employ iterative optimization methods such as the Dinkelbach algorithm [

12] and successive convex approximation (SCA) [

13,

14]. These approaches may achieve near-optimal solutions, but they are typically applied within a single time slot and therefore focus on instantaneous performance. For example, the authors in [

13,

14] maximized the weighted sum rate (WSR) or sum rate under perfect CSI, while the authors in [

12] improved energy efficiency under instantaneous minimum data rate constraints. The authors in [

15] studied sum rate maximization with instantaneous QoS constraints, and the authors in [

16] improved the average sum rate under imperfect CSI. However, these works fundamentally rely on instantaneous CSI and do not provide mechanisms for guaranteeing long-term QoS, which is essential in environments with channel fading, interference variability, and user mobility. Similar reliability-aware and long-term optimization perspectives have recently been investigated in related wireless and edge computing systems [

17]. In particular, the instantaneous data rate constraints in [

12,

13] cannot guarantee long-term service requirements, and the average performance improvement in [

16] does not explicitly ensure long-term QoS for individual users.

In this situation, opportunistic scheduling has attracted attention as an effective approach for satisfying time-average QoS constraints. Prior works on OMA and NOMA show that opportunistic scheduling can achieve high throughput and maintain proportional fairness, and studies on multi-carrier NOMA demonstrate that long-term QoS constraints can be satisfied using stochastic optimization [

18]. However, these approaches cannot be directly applied to RSMA because the RSMA structure requires joint optimization of common/private power allocation and precoder design, which significantly increases the complexity of long-term resource allocation. This creates a gap between RSMA’s theoretical benefits and its ability to provide long-term QoS guarantees in practical systems.

To bridge this gap, this paper develops an opportunistic scheduling framework for multi-carrier RSMA systems that explicitly incorporates time-average QoS constraints. The novelty of the proposed approach lies in the problem formulation and system-level integration, rather than in the optimization technique itself. By leveraging stochastic dual optimization, the proposed framework decomposes the long-term problem into tractable per-slot subproblems with adaptive effective weights. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed approach enables RSMA to achieve both high spectral efficiency and reliable long-term QoS guarantees in dynamic fading environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the system model and problem formulation.

Section 3 introduces the proposed scheduling framework.

Section 4 explains the detailed algorithms.

Section 5 provides simulation results.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

We consider a downlink system where a base station (BS) equipped with

transmit antennas communicates with

J single-antenna user equipments (UEs). The total bandwidth

B is divided into

N subcarriers. We define the subcarrier index set as

The transmit power allocated to subcarrier

is denoted by

, and the BS transmit-power constraint is given by

where

is the maximum available BS transmit power.

2.1. Channel Model

The complex channel vector between the BS and UE

j on subcarrier

n is modeled as

where

denotes the large-scale fading coefficient, and

represents the small-scale Rayleigh fading vector. The large-scale fading coefficient is expressed as

where

is the path loss at distance

between the BS and UE

j,

is the log-normal shadow fading component, and

is the BS transmit antenna gain.

2.2. Noise and Interference Model

The receiver noise consists of thermal noise and a receiver noise figure (NF). Letting

be the subcarrier bandwidth, the noise power on each subcarrier is given as

where

To incorporate external interference, we model the effective noise as

where

is the interference factor that captures the relative level of external interference.

2.3. RSMA Transmission Structure

RSMA generalizes both SDMA and NOMA and can offer superior performance. However, the number of common streams and SIC layers increases system complexity. Accordingly, to ensure practical implementation, we assume that each subcarrier is assigned to a UE pair and a simplified two-UE RSMA structure is adopted. Following [

12], zero-forcing (ZF) precoding is applied to the private streams, whereas the common stream employs a precoder designed to enhance the common rate of the scheduled UE pair.

For a UE pair

, where

denotes the set of all possible UE pairs, if subcarrier

n is assigned to this pair, the private rate of UE

, assuming perfect SIC of the common stream, is given by

The signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR)-related term

is defined as

where

denotes the normalized channel vector, and

is the power allocated to the private stream of UE

k on subcarrier

n. For compact notation, we define the ZF orthogonality factor as

which allows rewriting (

9) as

The decoding rate of the common stream for UE

is

where

denotes the power allocated to the common stream on subcarrier

n. Since both UEs must decode the common stream, the achievable common rate is

By substituting the ZF private precoder and the common stream precoder obtained as in [

19] into (

12), the common rate can be expressed in closed form as

where

To represent how the common rate is shared between the two UEs, let

denote the portion of the common rate allocated to UE

k, satisfying

We further define a binary scheduling variable

indicating whether subcarrier

n is assigned to UE pair

. That is,

if the pair is scheduled on subcarrier

n, and

otherwise. Using this notation, the total data rate of UE

j over all subcarriers can be expressed as

2.4. Optimization Problem

We now formulate the optimization problem considered in this work. To effectively capture long-term performance, we adopt a time-slotted system with time-varying channels. The objective is to maximize the long-term WSR while ensuring that each UE satisfies its long-term QoS requirement. Before presenting the optimization problem, we introduce two simplifying assumptions that reduce computational complexity while preserving the generality of the proposed scheduling framework.

We first assume equal per-stream power allocation within each subcarrier, i.e.,

Second, we assume equal common-rate splitting between the two UEs assigned to a subcarrier, i.e.,

These assumptions are introduced to simplify the intra-subcarrier RSMA transmission structure, so that the focus of this work remains on the design of the proposed scheduling framework, which will be detailed in the subsequent sections. While more flexible RSMA designs may allow additional degrees of freedom through per-stream power loading and adaptive common-rate splitting, incorporating such variables would significantly increase the coupling and nonconvexity of the per-slot optimization problem, making it difficult to solve.

It is important to emphasize that the adopted assumptions do not alter the fundamental principles of RSMA. In particular, the common and private message transmission structure, as well as the partial interference decoding mechanism, are fully preserved. Only the intra-subcarrier power and rate partitioning are simplified, which allows the resulting problem to remain tractable while retaining the essential interference management capability of RSMA.

Moreover, the proposed scheduling framework is not inherently tied to these specific assumptions. More sophisticated power allocation or common-rate splitting strategies can be incorporated without modifying the structure of the long-term stochastic optimization or the scheduling policy developed in this paper. A detailed characterization of the optimality gap with respect to fully adaptive RSMA designs is beyond the scope of this work and is left for future investigation.

With these assumptions, the long-term WSR maximization problem is formulated as the following stochastic optimization problem:

where

denotes the weight assigned to UE

j, and

represents the minimum required long-term average data rate for UE

j. In the optimization problem in (21), the objective function (21a) represents the WSR evaluated over an infinite time horizon. Constraint (21b) ensures that each UE meets its long-term QoS requirement, Constraints (21c) and (21d) enforce the per-slot transmit-power limitations at the BS, and Constraints (21e) and (21f) guarantee that at most one UE pair is scheduled on each subcarrier in each time slot.

4. Per-Slot Problem Solution

In this section, we address the per-time slot optimization problem that appears as the inner maximization step of the dual formulation derived in

Section 3. For a fixed dual vector

, problem (

) in (

26) aims to maximize the instantaneous WSR with effective weights

. The per-slot optimization problem can be written as

For simplicity, the slot index

t is omitted, as the problem is solved independently in each time slot. Constraints (30b)–(30e) enforce the per-slot BS power limit, the nonnegativity of allocated power, and the binary UE pair selection, while guaranteeing that at most one UE pair is scheduled on each subcarrier. Because the WSR is a nonlinear function of both

and

, the optimization problem (30) is a MINLP and is, in general, computationally intractable to solve exactly.

To efficiently solve (30), we decompose the problem into two sequential subproblems: (i) subcarrier–UE pair matching with fixed power, and (ii) power allocation optimization with fixed matching. This decomposition is widely adopted in prior work and aligns well with the structure of subcarrier-based multiuser transmission.

4.1. Subcarrier–UE Pair Matching Optimization

Fix the per-subcarrier power to the equal value

. Under this assumption, problem (30) reduces to the following integer linear program (ILP):

where

denotes the WSR contribution of assigning UE pair

to subcarrier

n when

. It is noteworthy that although the matching constraints are defined per subcarrier, the objective function includes user-specific dual variables associated with long-term QoS constraints, which introduce coupling across subcarriers and prevent purely greedy solutions from being optimal in general.

Although (31) contains binary variables, its constraint matrix has a special structure that enables an efficient solution.

Theorem 2.

The constraint matrix associated with the subcarrier–UE pair matching problem in (31) is totally unimodular (TU). Consequently, its LP relaxation always yields an integer optimal solution.

Sketch of Proof. Each variable appears in exactly one matching constraint, and the resulting constraint matrix is an incidence matrix of a partitioned assignment structure. Such matrices are known to be TU, and therefore every vertex of the relaxed feasible polytope is integral. □

Because of Theorem 2, the optimal UE pair matching can be obtained directly through an LP solver, yielding a polynomial-time solution.

4.2. Power Allocation Optimization

After determining the optimal matching

, we optimize the transmit power across subcarriers. The remaining problem is

where

represents the subcarrier contribution. Letting

denote the UE pair scheduled on subcarrier

n, that is,

and

for all

, the subcarrier contribution can be given as

Because all RSMA private and common rates are strictly increasing in , the following result holds.

Theorem 3.

In the per-slot power allocation problem (32)

, the optimal solution satisfiesThat is, the BS always allocates all available transmit power. Sketch of Proof. All terms are strictly increasing in . Any unused power can always increase the objective by assigning it to an arbitrary subcarrier, contradicting optimality. □

Using Theorem 3, we apply a projected gradient-based iterative update:

followed by

where

is a step size satisfying standard diminishing conditions.

4.3. Unified Algorithm

The proposed per-slot solution for problem () consists of two stages:

Stage 1 (Matching): Solve the LP relaxation of (31) to determine the optimal UE pair for each subcarrier.

Stage 2 (Power Allocation): For the obtained matching, solve (32) using projected gradient iterations to allocate power across subcarriers.

This two-stage approach provides an efficient and practical per-slot solution. The complete per-slot WSR maximization process is summarized in Algorithm 2, which integrates both the matching and power allocation stages.

| Algorithm 2 Per-Slot WSR Maximization for RSMA |

Require: Channel state , effective weights , total power , step sizes - 1:

Initialize per-subcarrier power for all n - 2:

Stage 1: Subcarrier–UE Pair Matching - 3:

for each subcarrier n and each pair do - 4:

Compute WSR metric using - 5:

end for - 6:

Solve the LP relaxation of (31) and obtain the optimal matching - 7:

For each n, determine the scheduled pair such that - 8:

Stage 2: Power Allocation - 9:

Set iteration index - 10:

repeat - 11:

for each subcarrier n do - 12:

Compute gradient - 13:

end for - 14:

Select an anchor subcarrier index k - 15:

for each do - 16:

Update - 17:

end for - 18:

Set - 19:

- 20:

until convergence of or maximum iteration is reached - 21:

Output: and as the per-slot scheduling and power allocation solution

|

Remark 2

(Computational Complexity Discussion). The proposed scheduling framework is designed to maintain tractable per-slot complexity. Specifically, the dual update step involves simple scalar operations per user and incurs negligible overhead. The main computational burden lies in solving the per-slot problem , which is decomposed into a subcarrier–UE pair matching stage and a power allocation stage. The matching problem is solved via a linear program with a TU structure, resulting in polynomial-time complexity. The subsequent power allocation is handled by a gradient-based iterative method with a limited number of iterations. As a result, the overall per-slot complexity scales polynomially with the number of users and subcarriers, making the proposed framework suitable for centralized scheduling implementations with moderate system dimensions. Further complexity reduction via heuristic matching or iteration truncation is possible and left for future work.

5. Numerical Results

This section presents numerical results illustrating the performance of the proposed opportunistic RSMA scheduling framework. All simulations follow the system model described in

Section 2. Unless otherwise specified, all data rates are shown in bps/Hz.

5.1. Simulation Setup

We evaluate the proposed scheduling framework under the system model described in

Section 2. The BS uses

antennas and serves

users. We allocate a total bandwidth of

MHz and divide it uniformly into

subcarriers, resulting in

MHz per subcarrier. The BS transmits with a total power of

W.

We compute the noise power on each subcarrier using a thermal noise density of

dBm/Hz and a receiver noise figure of

dB, following (

5) and (

6). We apply an antenna gain of

dB. To capture external interference, we model the effective noise as

with interference factor

. We distribute users uniformly within a ring-shaped region defined by inner radius

m and outer radius

m. The BS and UE heights are set to

m and

m, respectively. We operate at carrier frequency

MHz.

With these settings, we model the large-scale fading using the Hata Urban model:

In addition, we generate shadow fading as a log-normal random variable with standard deviation

dB.

5.2. RSMA-NOMA Performance Comparison

We compare the proposed method against a baseline two-user NOMA scheme. To ensure a fair and controlled comparison, we apply the following setup. Both RSMA and NOMA employ the same subcarrier–UE pair matching, which we obtain from the LP relaxation of (31). For NOMA, the power allocation within each scheduled user pair is determined using the strategy proposed in [

25], which is optimal for two-user NOMA under the considered channel model and can be straightforwardly adapted to our system setting. All remaining system components, including channel realizations, noise power, interference levels, and the overall scheduling procedure, are kept identical for both schemes. This guarantees that any performance difference arises solely from the physical-layer transmission strategy.

Figure 1 illustrates the WSR performance as functions of the number of subcarriers

N and the number of users

J in

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b, respectively. The results show that RSMA consistently outperforms NOMA across all considered scenarios. Moreover, as

N or

J increases, the performance gap becomes more pronounced, owing to the enhanced flexibility of RSMA in managing interference through joint private and common stream transmission. In contrast, despite employing optimal power allocation on each subcarrier, NOMA remains fundamentally limited by its two-user superposition and successive interference cancellation (SIC) structure, which restricts its ability to flexibly manage multiuser interference.

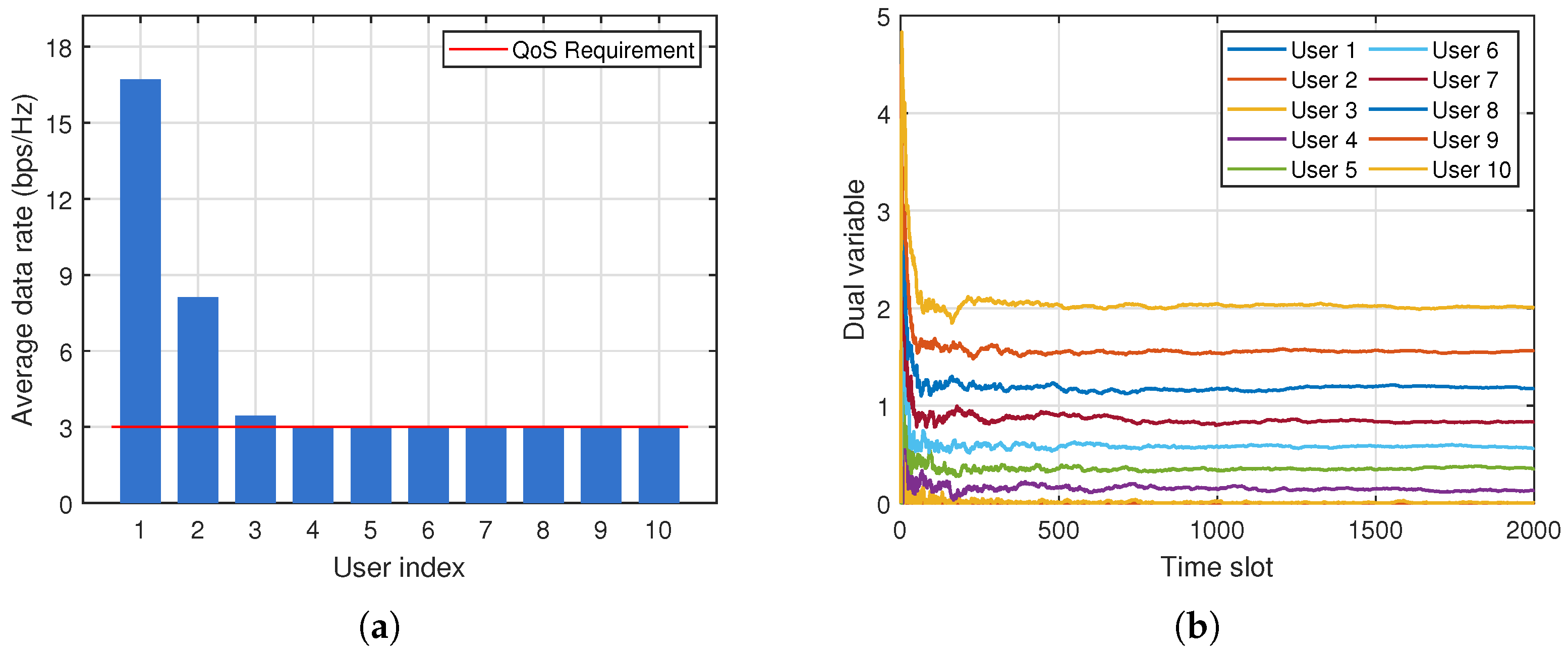

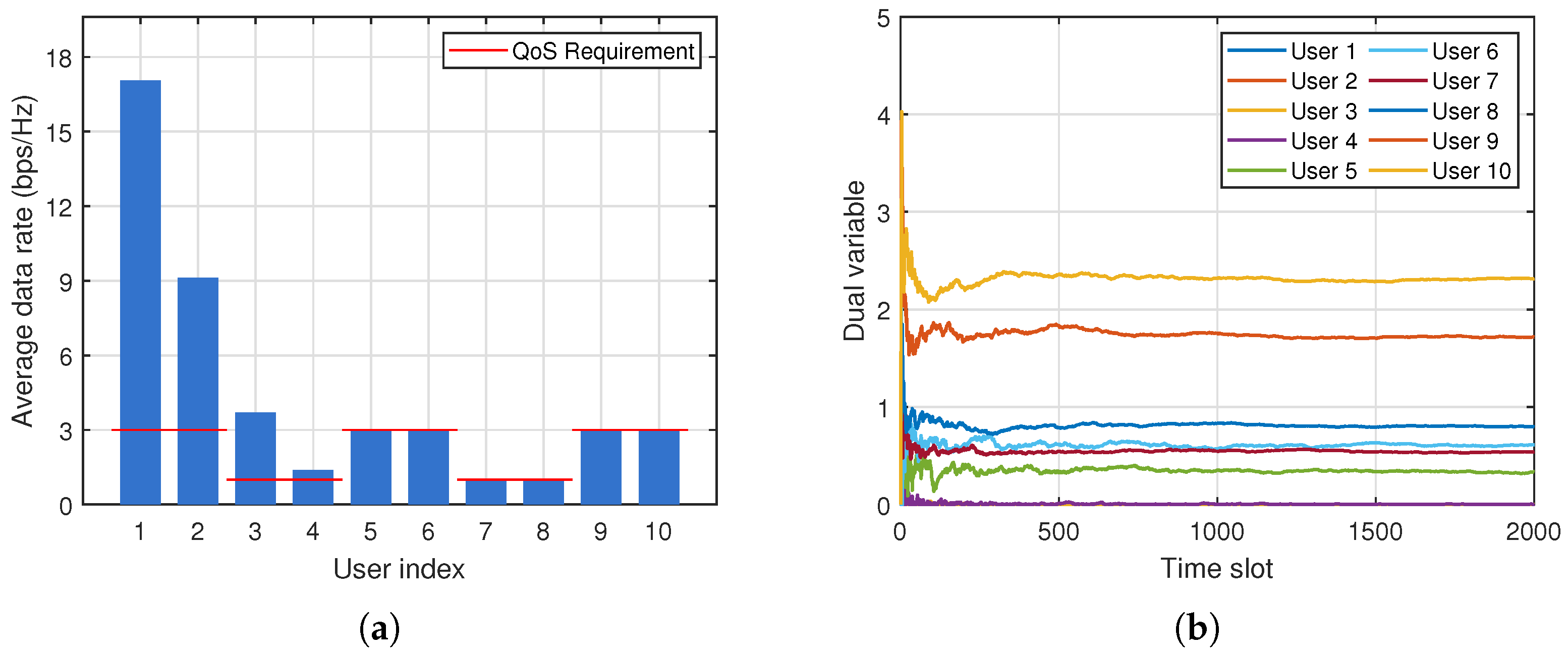

5.3. Long-Term QoS Satisfaction Analysis

We now evaluate the long-term QoS satisfaction achieved by the proposed dual-based opportunistic scheduling framework.

To clearly observe QoS satisfaction, user locations are set deterministically as

The dual variables are updated over 2000 time slots, each using an independently sampled channel realization.

We consider two scenarios:

Uniform QoS: all users require bps/Hz.

Heterogeneous QoS: users require 3 bps/Hz, while users require 1 bps/Hz.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show that all users meet their long-term QoS requirements in both scenarios. Users closer to the BS achieve higher long-term rates due to stronger channels, whereas distant users obtain lower rates. The dual update mechanism automatically compensates for this disparity by increasing the

values of weaker users, which raises their scheduling priority.

In the heterogeneous QoS scenario, users with stricter QoS requirements often experience early rate deficits. Their dual variables therefore increase more aggressively, which boosts their scheduling priority until their long-term rate requirements are satisfied. Consequently, users with larger QoS targets tend to converge to higher steady-state values, although the exact values depend on channel conditions and scheduling dynamics.

In summary, the proposed RSMA-based opportunistic scheduler achieves (i) reliable long-term QoS satisfaction, (ii) significantly higher WSR than NOMA, and (iii) robust adaptation to heterogeneous user demands and channel disparities.

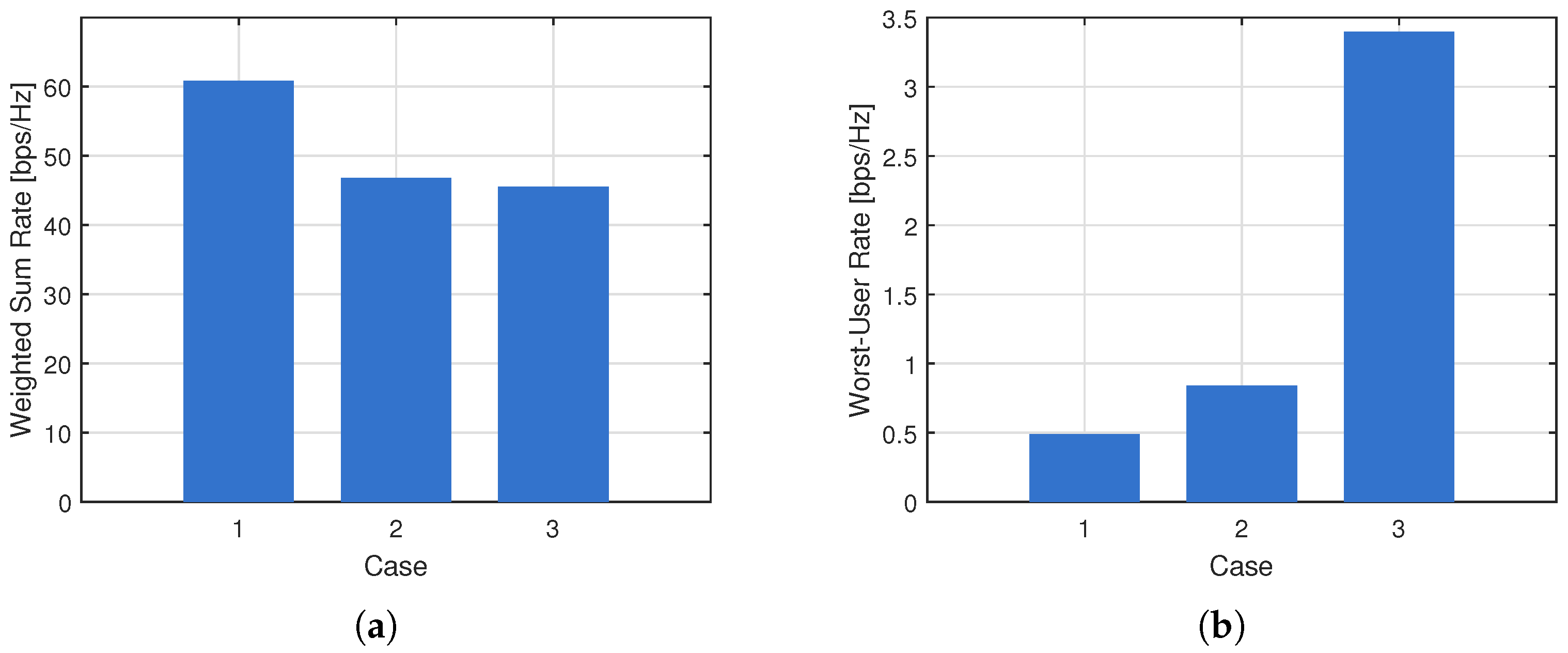

5.4. Impact of Weight Selection

To further examine the robustness of the proposed scheduling framework with respect to system design parameters, we investigate the impact of different WSR weight configurations. In particular, this study explores how user-priority weighting affects the long-term performance of the proposed approach, while keeping the minimum average rate requirements unchanged.

We consider three different WSR weight configurations, while fixing the minimum average rate requirement of all users to bps/Hz. The user locations are identical to those in the previous experiments, where users with smaller indices are located closer to the base station and thus experience more favorable average channel conditions. The weight vectors are normalized to have the same total sum and are designed such that larger weights are progressively assigned to users with poorer channel conditions. Specifically, Case 1 employs uniform weights across all users, whereas in Case 2 and Case 3, increasing priority is given to users with higher indices.

Figure 4 shows the resulting long-term performance over 2000 time slots, where independent channel realizations are generated at each slot. As shown in

Figure 4a, the weighted sum rate decreases from Case 1 to Case 3. This behavior is expected, since assigning larger weights to users with poorer channel conditions forces the scheduler to allocate more resources to satisfy their QoS requirements, thereby reducing the achievable system-level throughput. In contrast,

Figure 4b shows that the achievable rate of the weakest user increases significantly as its associated weight becomes larger. This confirms that the proposed scheduling framework effectively adapts resource allocation according to the prescribed weight configuration, prioritizing disadvantaged users when required.

These results highlight the flexibility and robustness of the proposed RSMA-based scheduling framework. By adjusting the user weights, the system can explicitly control the tradeoff between spectral efficiency and user fairness, while still satisfying the long-term QoS constraints for all users.