Close-Form Design Quantiles Under Skewness and Kurtosis: A Hermite Approach to Structural Reliability

Abstract

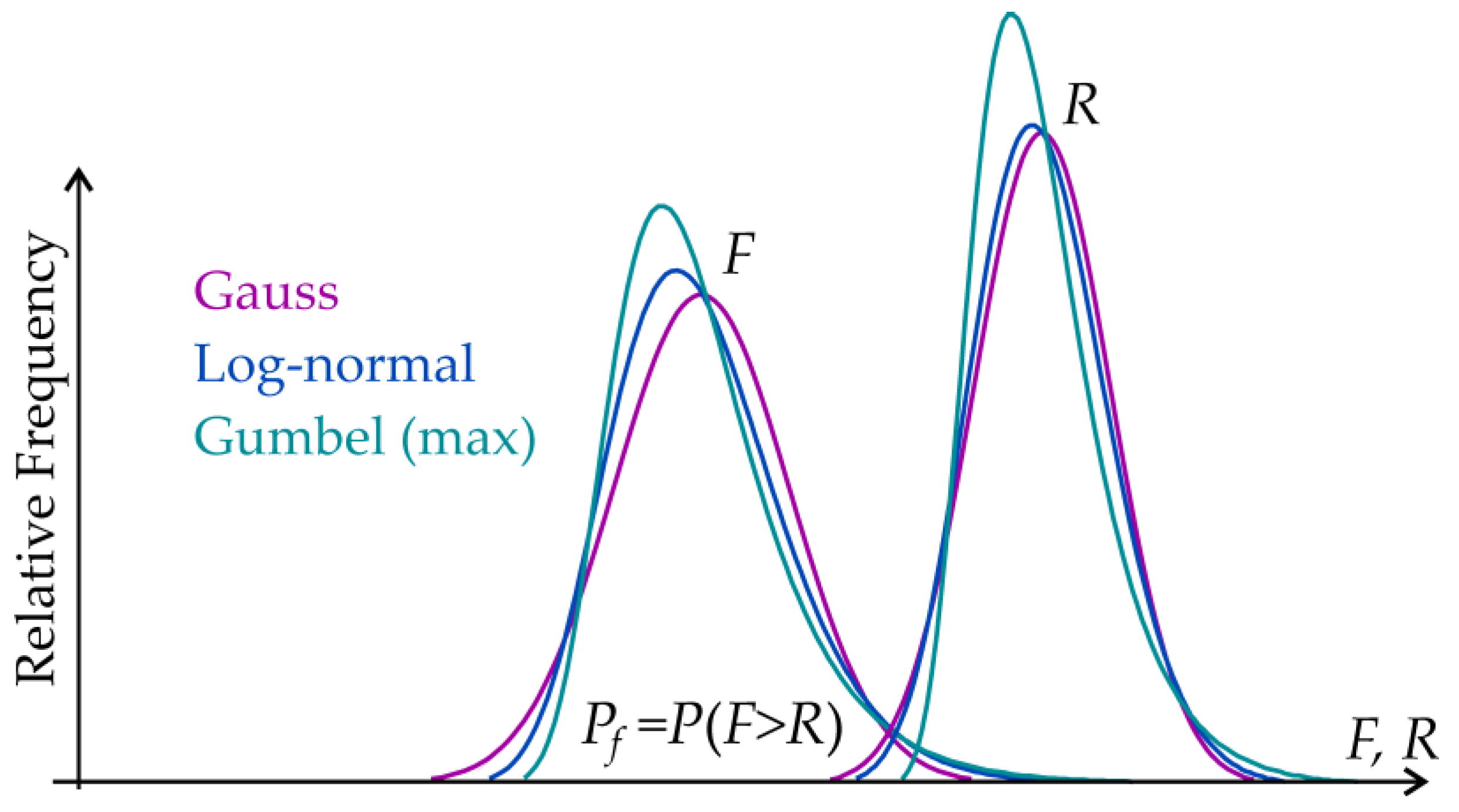

1. Introduction

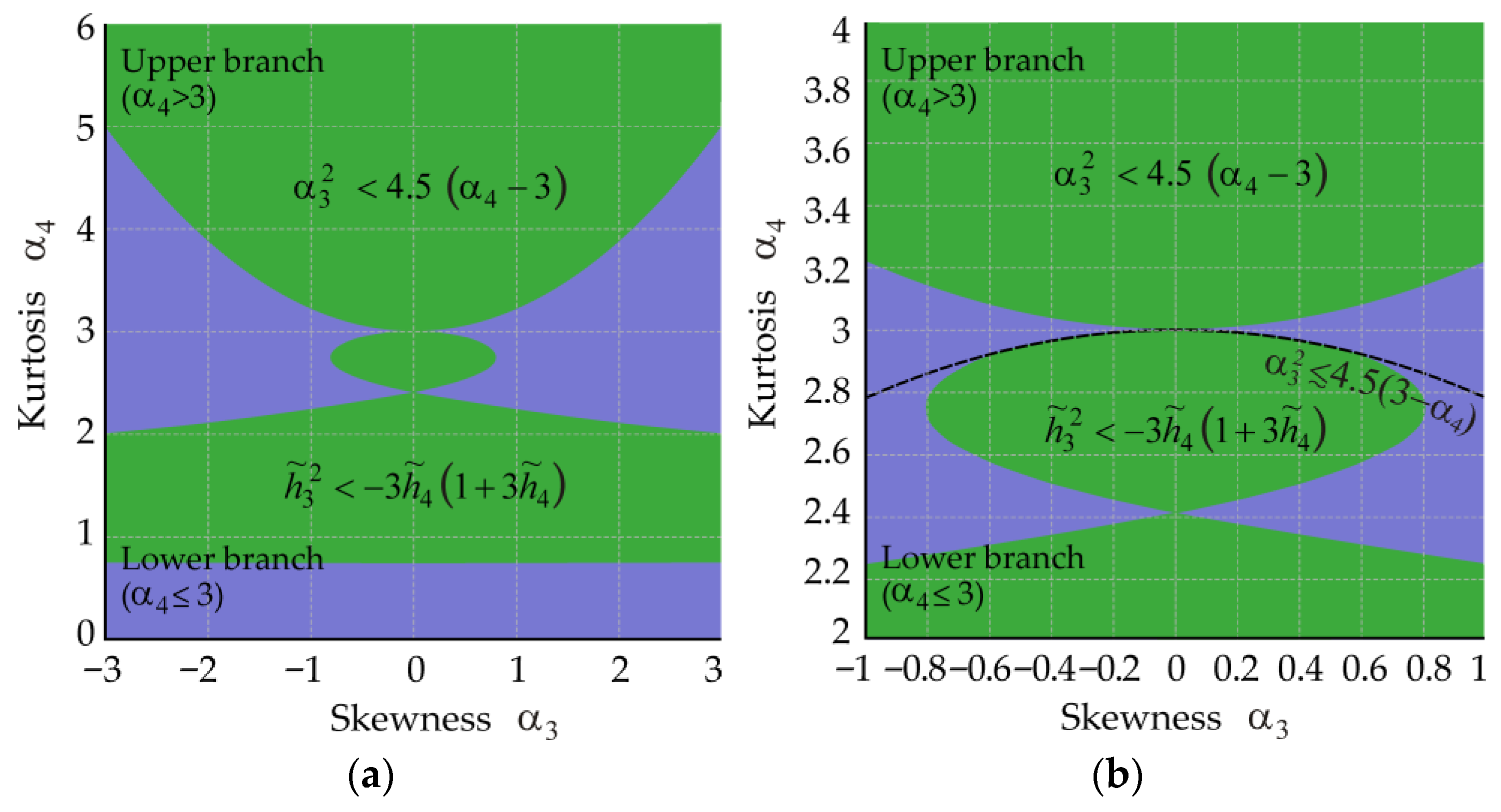

2. Hermite Models for Tail-Sensitive Reliability

3. Hermite Model: Map, Densities, and Properties

3.1. Polynomial Map and Parameterisation

3.2. Density Derivations

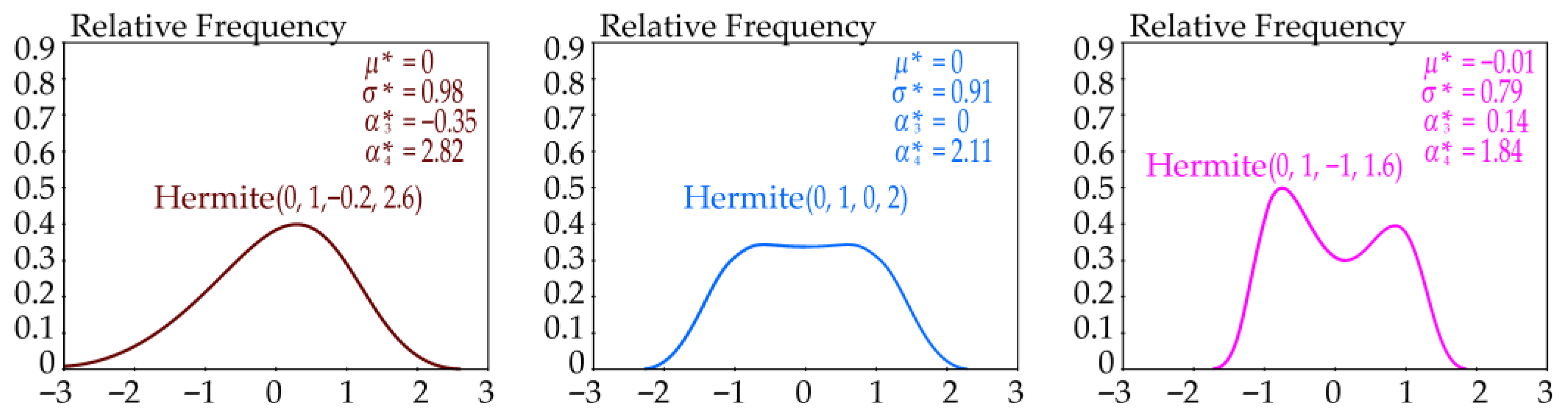

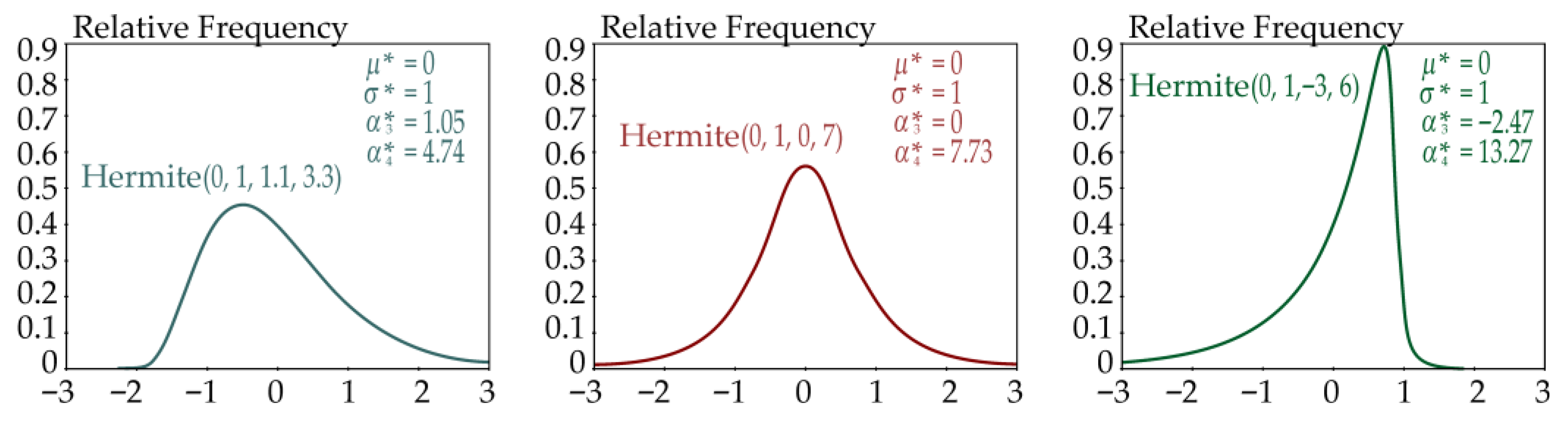

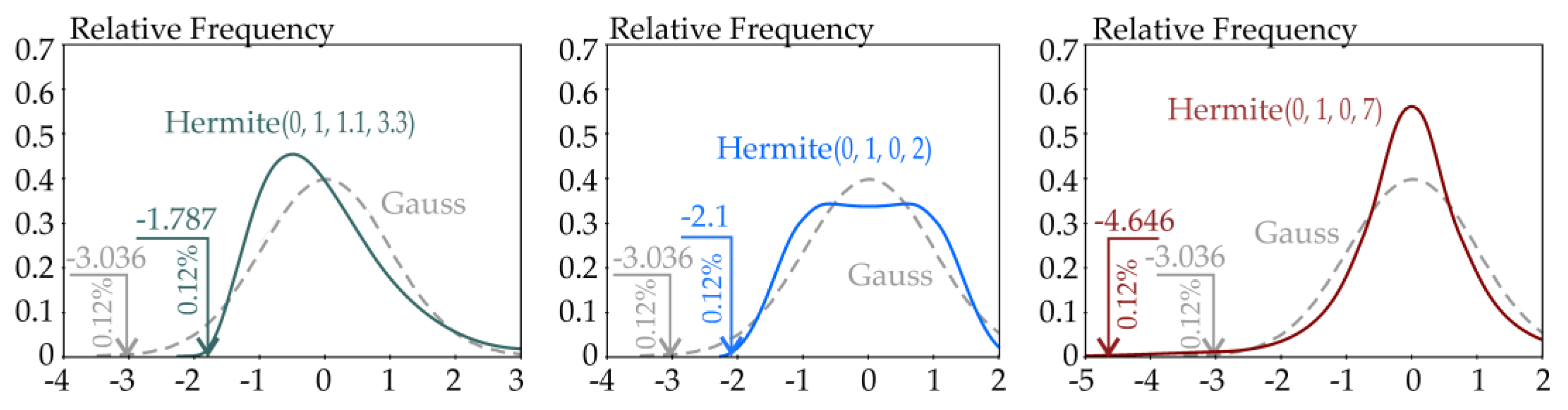

3.2.1. Lower-Branch Density (α4 ≤ 3)

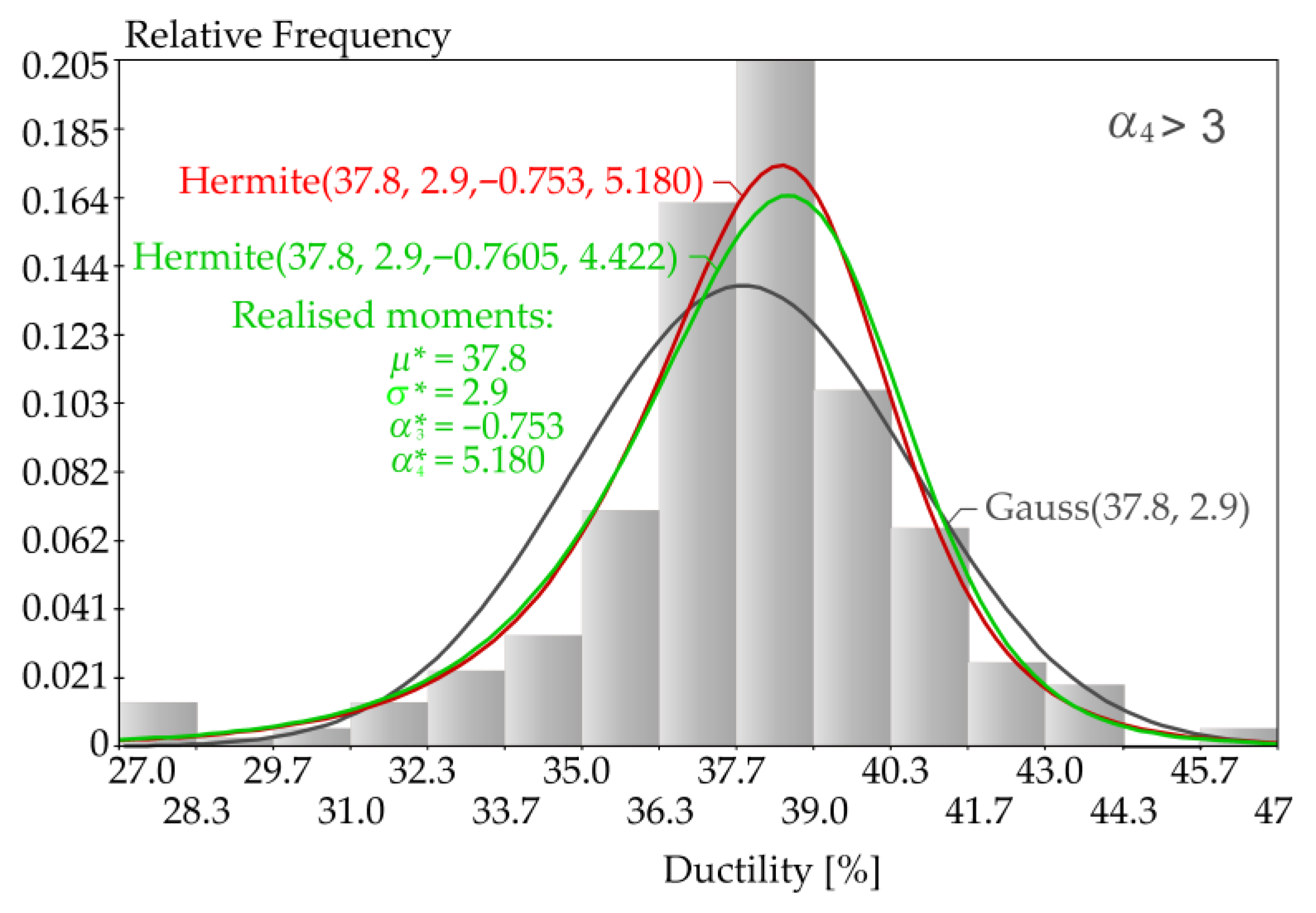

3.2.2. Upper-Branch Density (α4 > 3)

3.3. Properties and Admissible Sets

3.3.1. Non-Negativity and Monotonicity

3.3.2. Realised Moments

3.4. Implementation and Workflow

- Compute , and kt from α3 and α4.

- Select the branch: apply the Winterstein correction for α4 ≤ 3, or the Cardano inversion for α4 > 3.

- Verify the admissibility conditions, Equation (25) for the lower branch or Equation (27) for the upper branch.

- Evaluate the density using the function above.

- If the admissibility conditions are violated, the Hermite PDF cannot be used directly. In such cases, an alternative parametric or non-parametric model, which is better suited to the empirical histogram, must be adopted.

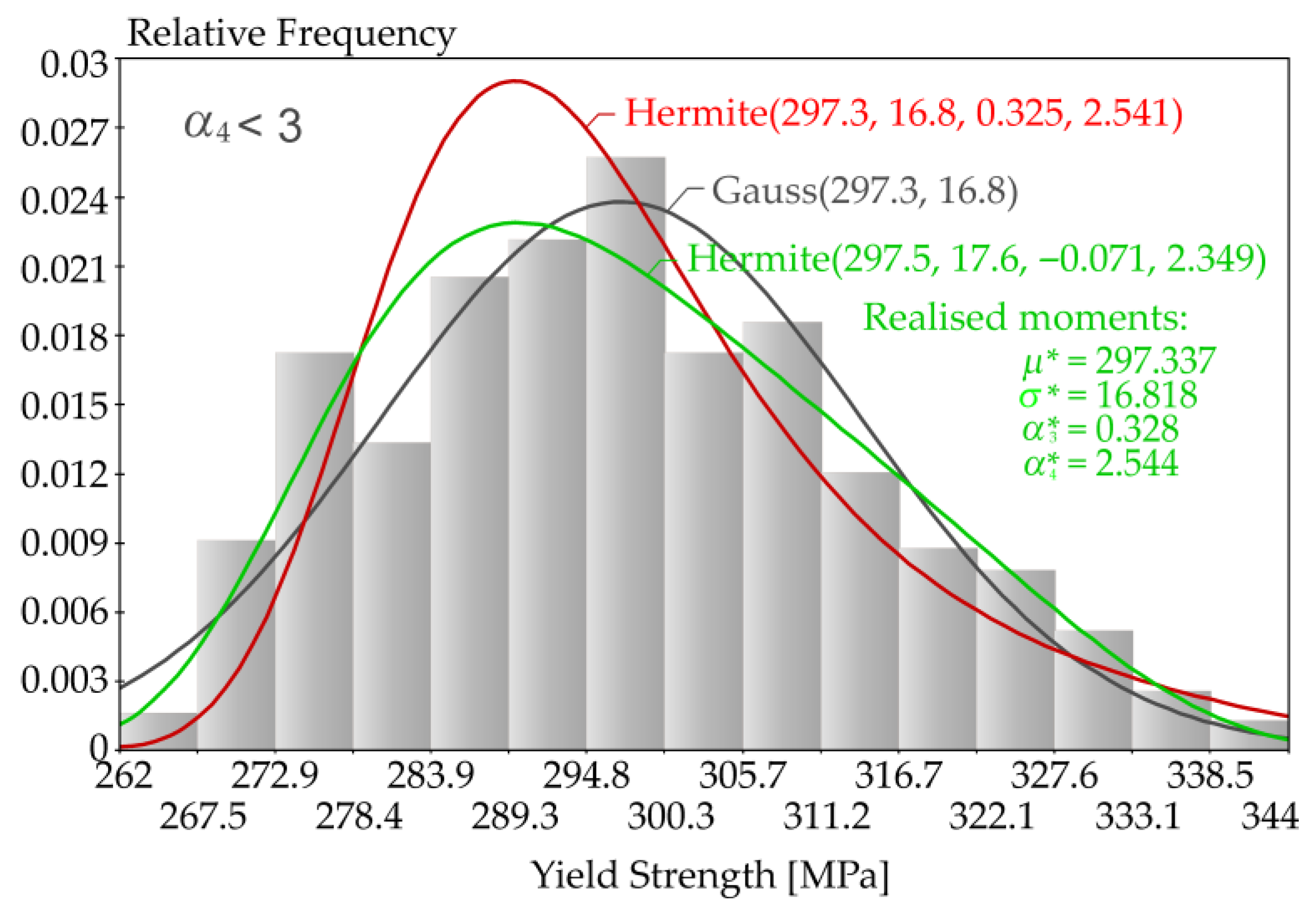

4. Fitting and Validation on Materials Data

4.1. S235 Yield Strength (Lower Branch)

4.2. S235 Ductility (Upper Branch)

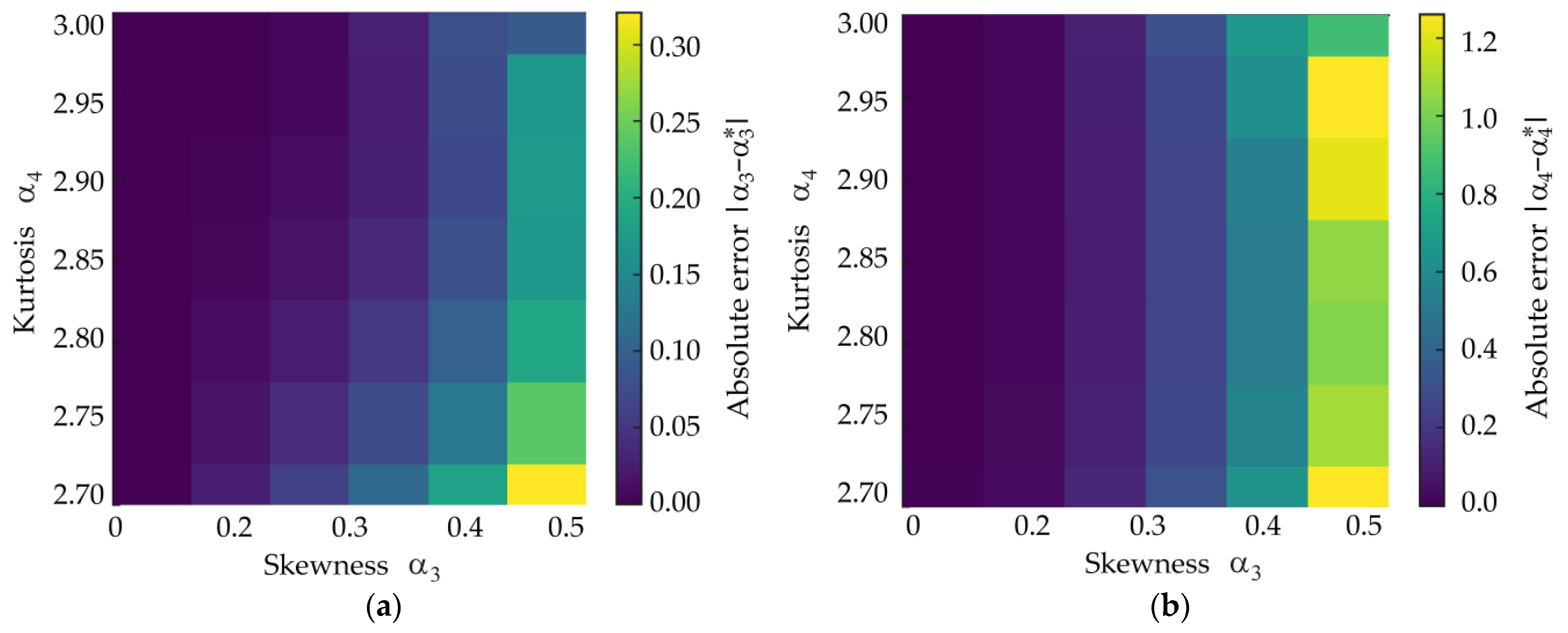

4.3. Extreme-Moment Inputs

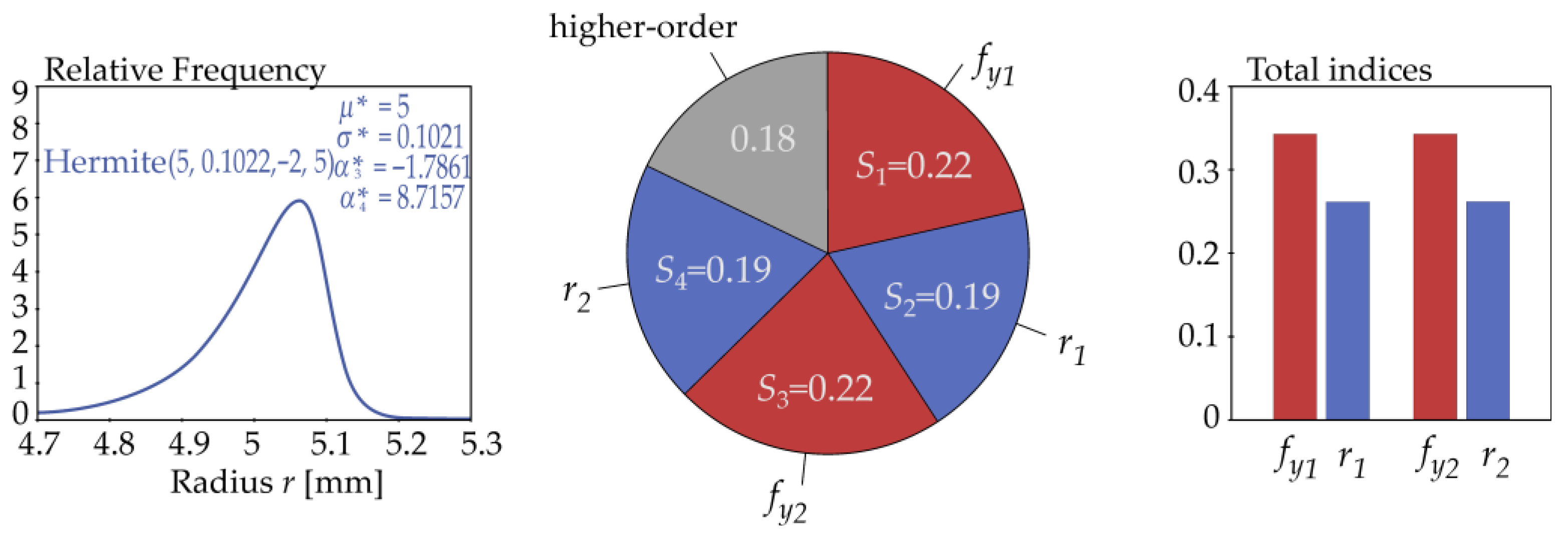

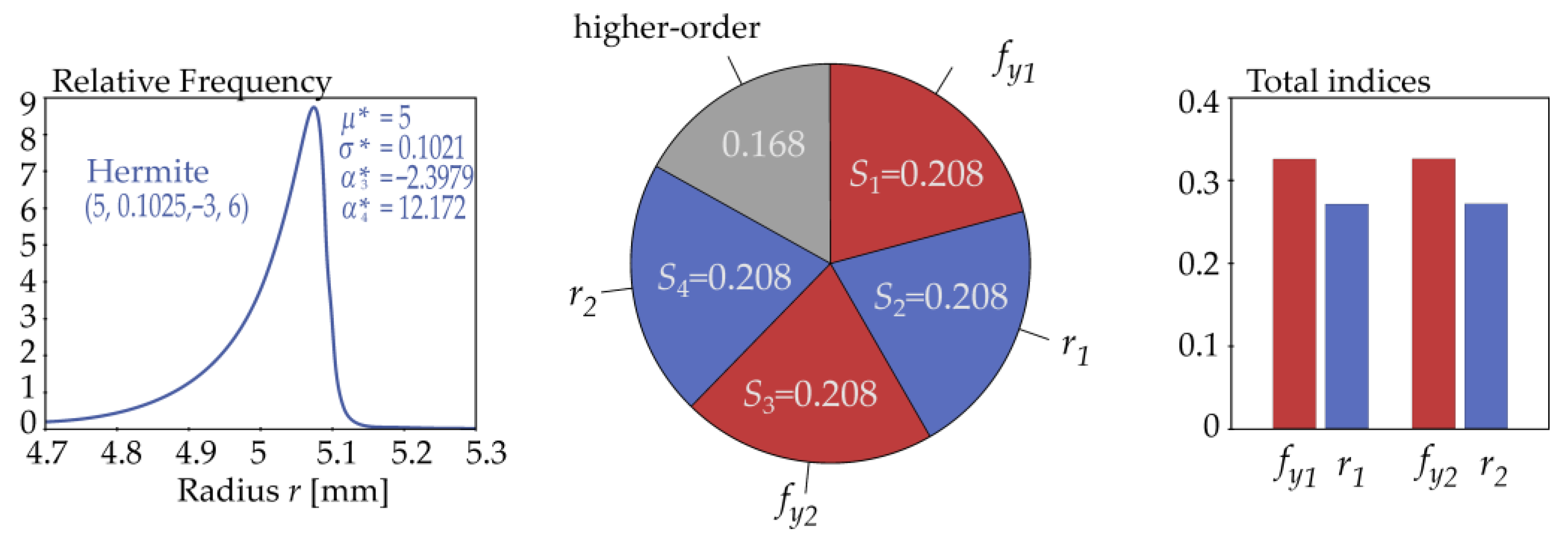

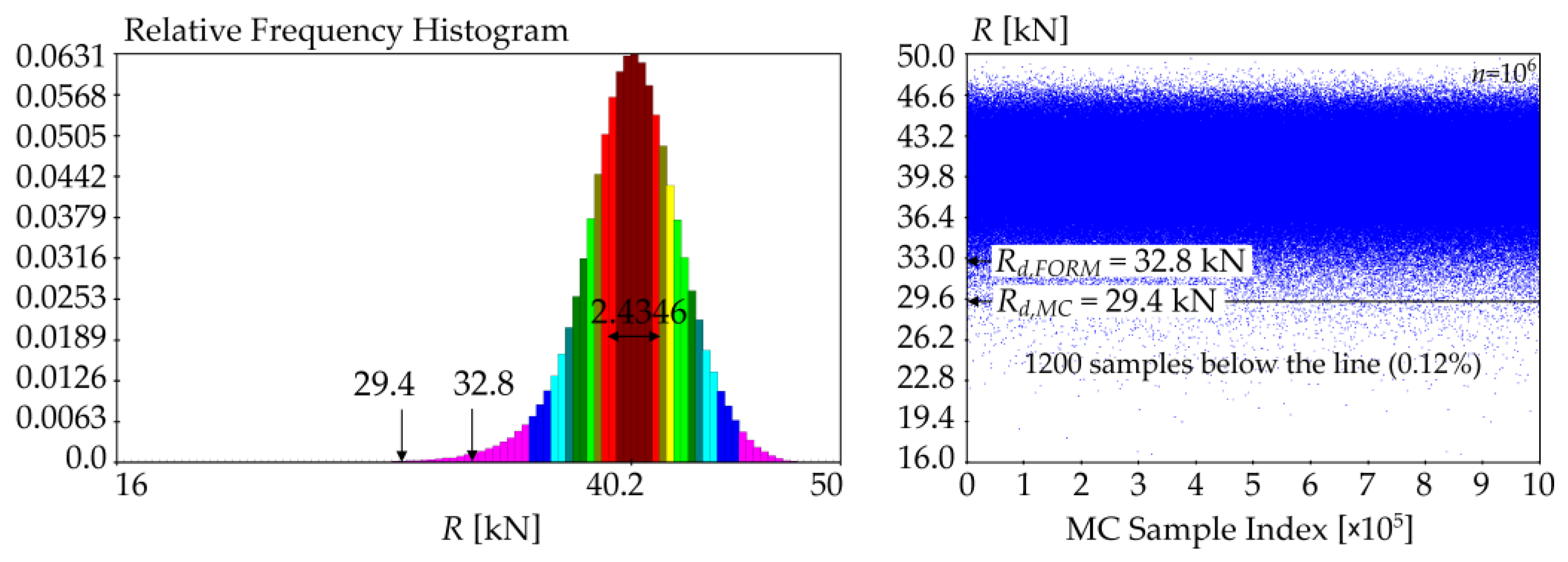

5. Reliability Application

5.1. Design Quantiles

5.1.1. EN 1990 Quantile

5.1.2. Hermite Quantile (Closed Form)

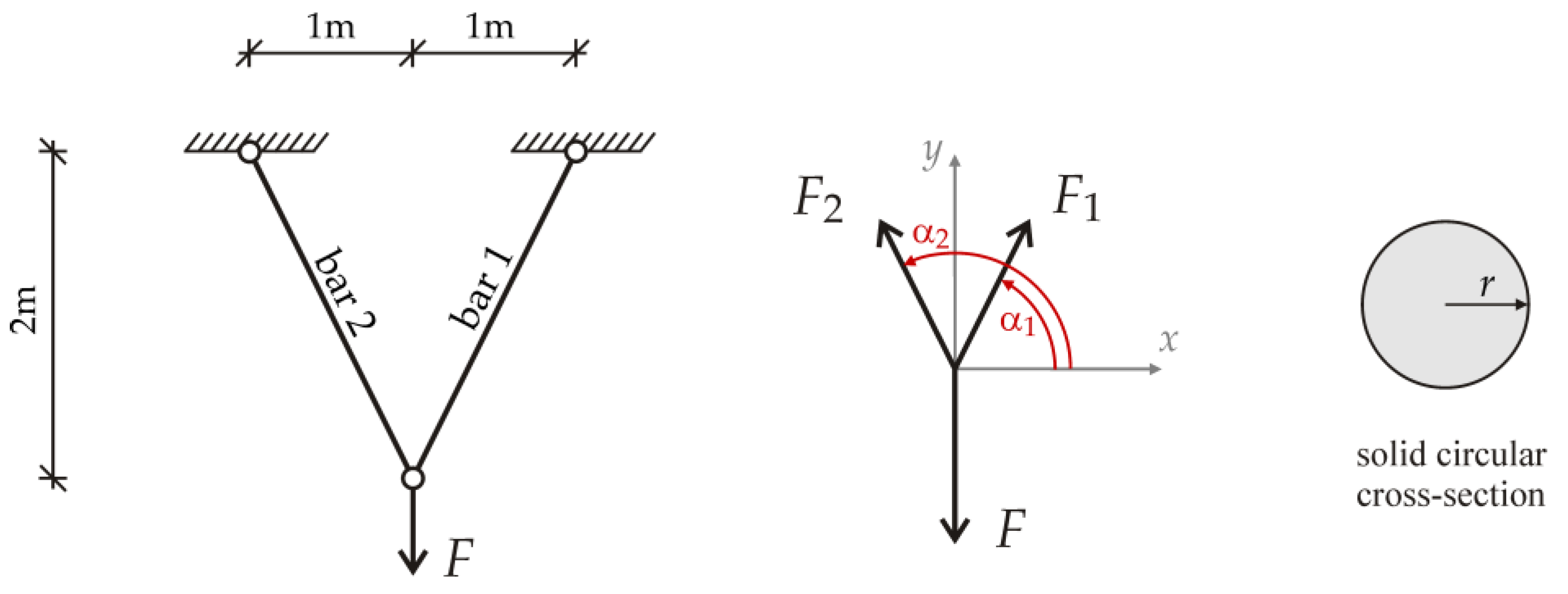

5.2. Case Study: Pin-Jointed Tie System

5.2.1. Inputs Random Quantities

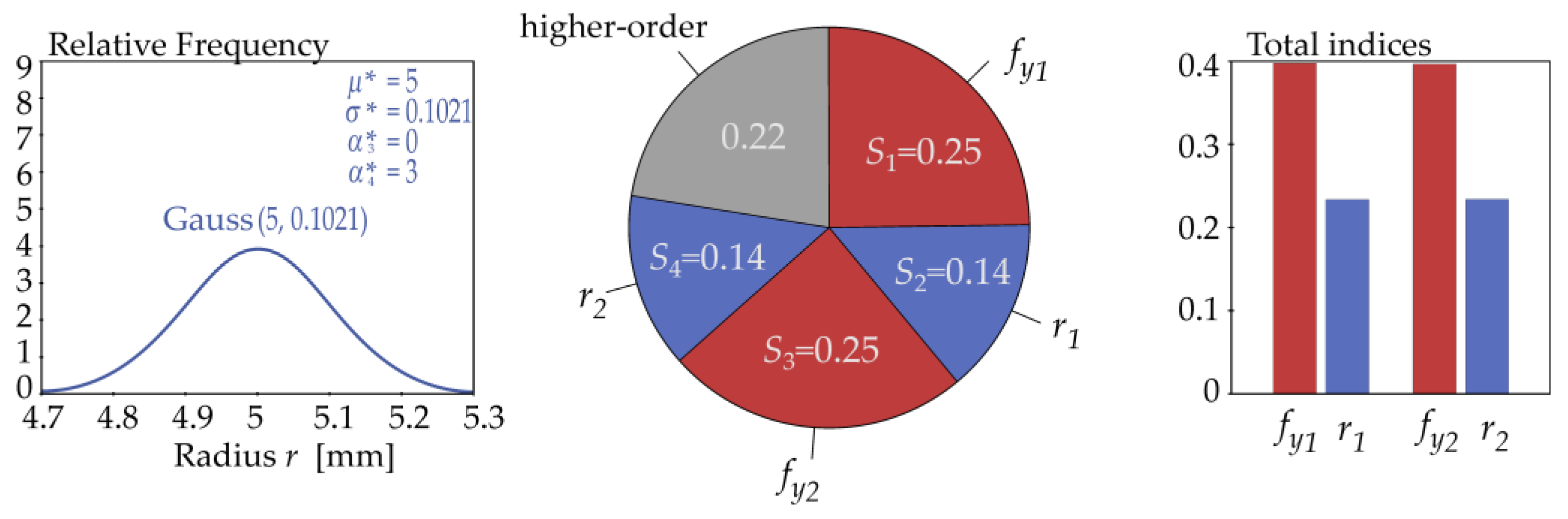

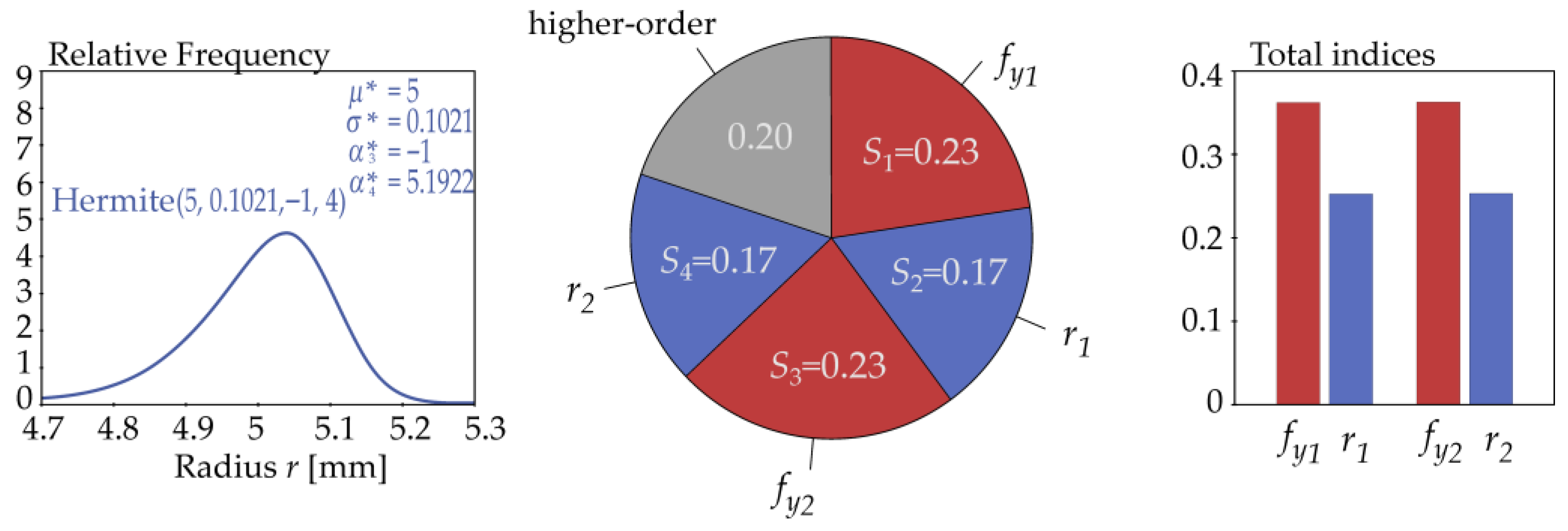

5.2.2. Sobol Sensitivity Analysis of Resistance

5.2.3. Output Statistics and Design Quantiles

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

| cdf | cumulative distribution function |

| EN 1990 | Eurocode 1990: Basis of Structural Design |

| FORM | First Order Reliability Method |

| GSA | Global Sensitivity Analysis |

| MC | Monte Carlo simulation |

| probability density function | |

| RC2 | Reliability Class 2 |

| SSA | Sobol Sensitivity Analysis |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- EN 1990:2002; Eurocode—Basis of Structural Design. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- Kamiński, M.; Błoński, R. Analytical and Numerical Reliability Analysis of Certain Pratt Steel Truss. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Kaewunruen, S. Machine learning and traditional approaches in shear reliability of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 251, 110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, X.; Zheng, W.; Liu, P. Improved Calculation of Load and Resistance Factors Based on Third-Moment Method. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, F.; Wang, F. A Second-Order Second-Moment Approximate Probabilistic Design Method for Structural Components Considering the Curvature of Limit State Surfaces. Buildings 2025, 15, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Dai, X. Extreme-Value Combination Rules for Tower–Line Systems Under Non-Gaussian Wind-Induced Vibration Response. Buildings 2025, 15, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yuan, G.; Li, C.B.; Zhang, X.; Li, L. Dynamic Analysis and Extreme Response Evaluation of Lifting Operation of the Offshore Wind Turbine Jacket Foundation Using a Floating Crane Vessel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Weng, G.; Cheng, Z. Influence of Load Partial Factors Adjustment on Reliability Design of RC Frame Structures in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, M.; Fang, W.; Li, Q.; Xu, K.; Huang, H.; Feng, Y. Time-Dependent Reliability Estimation of Bridge Structures with Auto-Correlated Stochastic Processes Based on the Gaussian Copula Function. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutanen, T. Combination of Variable Loads in Structural Design. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, Z. Reliability Analysis of the Lateral Torsional Buckling Resistance and the Ultimate Limit State of Steel Beams with Random Imperfections. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2015, 21, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, R.; Nassar, M. A New Exponential Distribution to Model Concrete Compressive Strength Data. Crystals 2022, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndeba, B.S.; El Alani, O.; Ghennioui, A.; Benzaazoua, M. Comparative Analysis of Seasonal Wind Power Using Weibull, Rayleigh and Champernowne Distributions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obulezi, O.J.; Semary, H.E.; Nadir, S.; Igbokwe, C.P.; Orji, G.O.; Al-Moisheer, A.S.; Elgarhy, M. Type-I Heavy-Tailed Burr XII Distribution with Applications to Quality Control, Skewed Reliability Engineering Systems and Lifetime Data. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 144, 2991–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Jiang, B.; Lei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W. Reliability Analysis of Normal, Lognormal, and Weibull Distributions on Mechanical Behavior of Wood Scrimber. Forests 2024, 15, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, Y.M.; Marikhin, V.A.; Myasnikova, L.P. Tensile Strength Statistics of High-Performance Mono- and Multifilament Polymeric Materials: On the Validity of Normality. Polymers 2023, 15, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhajjar, R. Fat-Tailed Failure Strength Distributions and Manufacturing Defects in Advanced Composites. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-H.; Lee, S.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Lim, J.-S. Reliability Assessment of Statistical Distributions for Analyzing Dielectric Breakdown Strength of Polypropylene. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanem, E.; Gramstad, O.; Babanin, A.; De Bin, R.; Trulsen, K. On the Distribution of Ocean Wave Crest Heights in Varying Wave Conditions. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2024, 10, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Xiong, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, S. Study on the Probabilistic Characteristics of Forces in the Support Structure of Heliostat Array Based on the DBO-BP Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, Q.; Mao, Y.; Chen, G.; Xue, L.; Lu, H.; Shi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Song, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Multi-Locus Genome-Wide Association Study and Genomic Selection of Kernel Moisture Content at the Harvest Stage in Maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 697688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, M.; Martínez-Cáceres, C.M.; Jornet-García, A.; Moya-Villaescusa, M.J. The Efficacy of a Deproteinized Bovine Bone Mineral Graft for Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Histologic Study in Humans. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S.H.; Dang, H.-K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Thai, D.-K. Stochastic Nonlinear Inelastic Analysis for Steel Frame Structure Using Monte Carlo Sampling. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindra, D.; Kala, Z.; Kala, J. Flexural Buckling of Stainless Steel CHS Columns: Reliability Analysis Utilizing FEM Simulations. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 188, 107002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterstein, S.R. Nonlinear Vibration Models for Extremes and Fatigue. J. Eng. Mech. 1988, 114, 1772–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achamyeleh, T.; Çamur, H.; Savaş, M.A.; Evcil, A. Mechanical strength variability of deformed reinforcing steel bars for concrete structures in Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhang, T.; Jin, Q. Investigation of Wind Pressure Dynamics on Low-Rise Buildings in Sand-Laden Wind Environments. Buildings 2025, 15, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Ren, C.; Liu, M.; Zhou, T. A Novel Non-Gaussian Analytical Wake Model of Yawed Wind Turbine. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2025, 259, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundu, M. Mathematical Model to Determine the Weld Resistance Factor of Asymmetrical Strength Results. Structures 2017, 12, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-G.; Lu, Z.-H. Estimation of Load and Resistance Factors Using the Third-Moment Method Based on the 3P-Lognormal Distribution. Front. Archit. Civ. Eng. China 2011, 5, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ji, X.; Zhao, Y.-G. Structural Reliability Assessment Using Quartic Normal Transformation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochocki, W.; Obara, P.; Radoń, U. Impact of the Wind Load Probability Distribution and Connection Types on the Reliability Index of Truss Towers. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2020, 58, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhao, Y.-G.; Lu, Z.-H. Unified Hermite Polynomial Model and Its Application in Estimating Non-Gaussian Processes. J. Eng. Mech. 2019, 145, 04019001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.-N.; Shen, F.-Q.; Cui, C.-X. The Inverse Transformation of L-Hermite Model and Its Application in Structural Reliability Analysis. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gurley, K.R.; Prevatt, D.O. Probabilistic Modeling of Wind Pressure on Low-Rise Buildings. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2013, 114, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, D.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Yoon, S.W. Non-Gaussian Properties and Extreme Values of Net Pressure on a Dome with a Central Opening. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nie, S.; Liu, M.; Yang, Q.; Guo, K. Two Parallel Cable Trusses-Supported Photovoltaic System: Extreme Wind-Induced Response and Displacement-Based Gust Response Factors. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerod. 2025, 265, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-G.; Lu, Z.-H. Fourth-Moment Standardization for Structural Reliability Assessment. J. Struct. Eng. 2007, 133, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-P.; Hu, D.-Z.; Zhang, L.-W.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y. L-Moments-Based FORM Method for Structural Reliability Analysis Considering Correlated Input Random Variables. Buildings 2023, 13, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Y.M. A New Distribution for Fitting Four Moments and Its Applications to Reliability Analysis. Struct. Saf. 2013, 42, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ding, C. Adaptive Hermite Distribution Model with Probability-Weighted Moments for Seismic Reliability Analysis of Nonlinear Structures. ASCE–ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2021, 7, 04021052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoël, V. Moment-Based Hermite Model for Asymptotically Small Non-Gaussianity. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 144, 116061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Lu, Z.-H.; Zhao, Y.-G. Simulating Non-Stationary and Non-Gaussian Cross-Correlated Fields Using Multivariate Karhunen–Loève Expansion and L-Moments-Based Hermite Polynomial Model. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 216, 111480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Pang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S.; Xu, B. A Novel Method for Simulating Large-scale 3D Non-Gaussian Random Fields in Geotechnical Engineering. Comput. Geotech. 2026, 189, 107621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.T.; Kim, H. Estimating Skewness and Kurtosis for Asymmetric Heavy-Tailed Data: A Regression Approach. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-G.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Lu, Z.-H. A Flexible Distribution and Its Application in Reliability Engineering. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 176, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Lu, Z.-H.; Li, C.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-G. Dynamic Reliability Analysis for Non-Stationary Non-Gaussian Response Based on the Bivariate Vector Translation Process. Probab. Eng. Mech. 2021, 66, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Hong, L. Study of the Kurtoses Transmission of Linear Structures under Stationary Non-Gaussian Random Loadings. J. Vib. Control 2025, 31, 1438–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Hong, L.; Zang, L. Research on Response Kurtosis Estimation in Linear Structures Subjected to Nonstationary Random Excitation: An Envelope-Based Method. Shock Vib. 2024, 2024, 9998563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Z. Influence of Ground Motion Non-Gaussianity on Seismic Performance of Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Yu, K.; Fan, W.; Xin, S. Frequency-Domain Analysis and Dynamic Reliability Assessment of Random Vibration for Non-Classically Damped Linear Structure under Non-Gaussian Random Excitations. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264, 111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yao, W. A Conditional Probability Density Function Model for Fatigue Damage Estimation in Broadband Non-Gaussian Stochastic Processes. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 197, 108958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Wang, C. Estimation of Fatigue Damage under Uniform-Modulated Non-Stationary Random Loadings Using Evolutionary Power Spectral Density Decomposition. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 226, 112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, A.; Wolfsteiner, P. Fast Assessment of Non-Gaussian Inputs in Structural Dynamics Exploiting Modal Solutions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 112396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodahl, N.; Skrede, S.O.; Grytoyr, G.; Gregersen, K. Fatigue Damage Summation with Bias Correction. Mar. Struct. 2026, 105, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Sweetman, B.; Tang, S. Impact of Non-Gaussian Winds on Blade Loading and Fatigue of Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J. Novel Hermite Polynomial Model Based on Probability-Weighted Moments for Simulating Non-Gaussian Stochastic Processes. J. Eng. Mech. 2024, 150, 04024006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-G.; Wang, T.; Ji, X.; Huang, G. Quartic Hermite polynomial model-based translation method for extreme wind load estimation. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 245, 105653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianculescu, D.; Anghel, C.G. Innovative Explicit Relations for Weibull Distribution Parameters Based on K-Moments. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Neuhäusler, J.; Denk, M.; Renken, F.; Kellner, L.; Schubnell, J.; Jung, M.; Rother, K.; Ehlers, S. Statistical Characterization of Stress Concentrations along Butt Joint Weld Seams Using Deep Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaras, Ž.; Lukoševičius, V.; Bazaraitė, E. Structural Materials Durability Statistical Assessment Taking into Account Threshold Sensitivity. Metals 2022, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Ka, T.A.; Li, X.; Sun, K.; Qin, K.; Noor E Khuda, S.; Tafsirojjaman, T. Evaluation of Tensile Strength Variability in Fiber Reinforced Composite Rods Using Statistical Distributions. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 10, 1506743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, M.; Rehman, K.U.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Shatanawi, W. Predicting the Strengths of Date Fiber Reinforced Concrete Subjected to Elevated Temperature Using Artificial Neural Network and Weibull Distribution. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra de Lima, N.; Pontes, M.; Silva, D.; Manta, R.C.; Teti, B.S.; Nascimento, H.C.B.; Santos, L.B.T.; Lima, N.B. Evaluation of Probability Distributions in the Study of Characteristic Compressive Strength of Metakaolin Concrete Blocks. Ambiente Construído 2025, 25, e138069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, C.-C.; Ho, N.-K. Best Fit of Statistical Distribution to Compressive Strength of Green Concrete Produced in the Northern area of Vietnam. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcher, J.; Kala, Z.; Holický, M.; Fajkus, M.; Rozlívka, L. Design Characteristics of Structural Steels Based on Statistical Analysis of Metallurgical Products. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2004, 60, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, Z.; Melcher, J.; Puklický, L. Material and Geometrical Characteristics of Structural Steels Based on Statistical Analysis of Metallurgical Products. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2009, 15, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockenbrough, R.L. MTR Survey of Plate Material Used in Structural Fabrication—Final Report, Part A: Yield–Tensile Properties; American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC): Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kala, Z. Sensitivity Analysis in Probabilistic Structural Design: A Comparison of Selected Techniques. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharian, P.; Naderpour, H.; Sharbatdar, M.K.; Ghasemi, S.H. Advancements in structural target reliability: A comprehensive examination of theories and practical applications (2013–2024). Structures 2024, 66, 106930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panther, L.; Wagner, W.; Freitag, S. A Consistently Linearized Spectral Stochastic Finite Element Formulation for Geometric Nonlinear Composite Shells. Comput. Mech. 2025, 75, 1655–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puman, E.; Lellep, J. Analysis of Elastic Conical Shells of Variable Thickness with Rib-reinforcement. Acta Comment. Univ. Tartu. Math. 2025, 29, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benasciutti, D.; Tovo, R. Frequency-based Analysis of Random Fatigue Loads: Models, Hypotheses, Reality. Mater. Wiss. Werksttech. 2018, 49, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 10060:2003+A1:2008; Hot Rolled Round Steel Bars for General Purposes—Dimensions and Tolerances on Shape and Mass. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- Kala, Z.; Valeš, J.; Jönsson, J. Random Fields of Initial Out of Straightness Leading to Column Buckling. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2017, 23, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quantity | Density | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield strength fy1 | 297.5 | 17.6 | −0.071 | 2.349 | Hermite |

| Radius r1 | 5 | 0.1021 | Hermite | ||

| Yield strength fy2 | 297.5 | 17.6 | −0.071 | 2.349 | Hermite |

| Radius r2 | 5 | 0.1021 | Hermite |

| Density of Input Radius r | [kN] | [kN] | [-] | [-] | Rd,FORM [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauss(5, 0.1021) | 40.1431 | 2.2494 | 0.2161 | 3.0073 | 33.3048 |

| Hermite(5, 0.1021, −1, 4) | 40.1513 | 2.3351 | −0.0784 | 3.6834 | 33.0523 |

| Hermite(5, 0.1022, −2, 5) | 40.1611 | 2.4039 | −0.4209 | 5.9759 | 32.8532 |

| Hermite(5, 0.1025, −3, 6) | 40.1702 | 2.4539 | −0.6874 | 7.8546 | 32.7103 |

| Density of Output Resistance R | Rd,HERM-INT [kN] (n. integration) | Rd,HERM [kN] Equation (47) | Rd,FORM [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hermite(40.1443, 2.2517, 0.2051, 2.898) | 34.0463 | 34.2636 | 33.3048 |

| Hermite(40.1513, 2.3351, −0.0781, 3.6634) | 31.8476 | 31.8312 | 33.0523 |

| Hermite(40.1611, 2.4039, −0.4164, 5.5009) | 29.0760 | 29.0463 | 32.8532 |

| Hermite(40.1702, 2.4539, −0.6821, 6.7349) | 27.5294 | 27.4957 | 32.7103 |

| Input Model for Radius r | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | Rd,FORM [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauss(5, 0.1021) | 40.1388 | 2.2484 | 0.2158 | 3.0188 | 33.3037 |

| Hermite(5, 0.1021, −1, 4) | 40.1458 | 2.3343 | −0.0510 | 3.3672 | 33.0496 |

| Hermite(5, 0.1022, −2, 5) | 40.1583 | 2.3928 | −0.3085 | 3.9855 | 32.8843 |

| Hermite(5, 0.1025, −3, 6) | 40.1692 | 2.4346 | −0.5002 | 4.6400 | 32.7681 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kala, Z. Close-Form Design Quantiles Under Skewness and Kurtosis: A Hermite Approach to Structural Reliability. Mathematics 2026, 14, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010070

Kala Z. Close-Form Design Quantiles Under Skewness and Kurtosis: A Hermite Approach to Structural Reliability. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleKala, Zdeněk. 2026. "Close-Form Design Quantiles Under Skewness and Kurtosis: A Hermite Approach to Structural Reliability" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010070

APA StyleKala, Z. (2026). Close-Form Design Quantiles Under Skewness and Kurtosis: A Hermite Approach to Structural Reliability. Mathematics, 14(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010070