Lightweight and Accurate Table Recognition via Improved SLANet with Multi-Phase Training Strategy

Abstract

1. Introduction

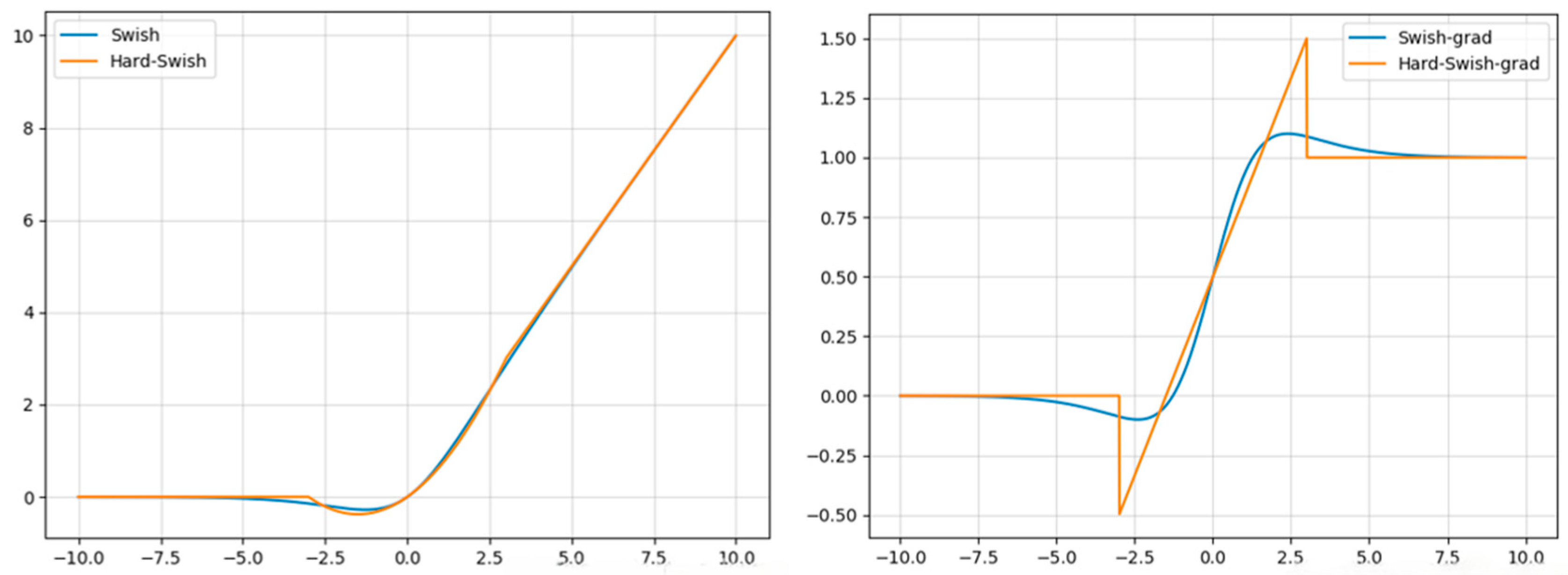

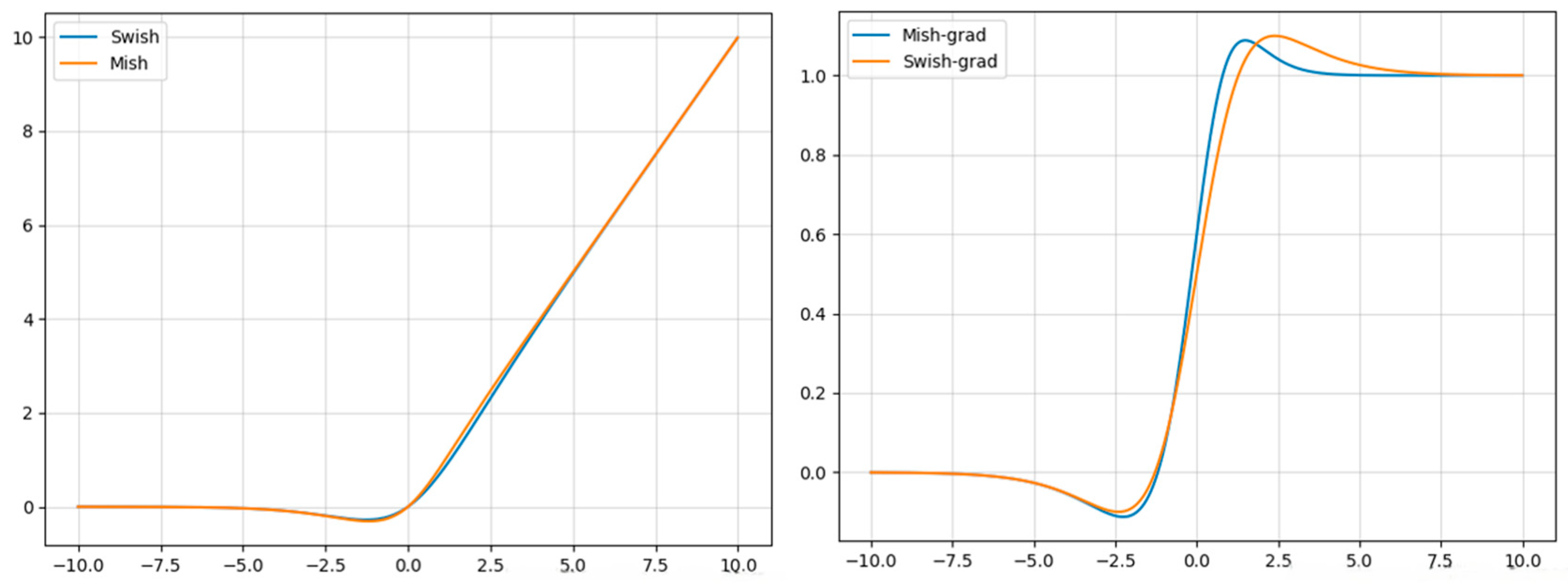

- Activation Function Optimization. We replace H-Swish with the smoother and fully differentiable Mish activation function, improving feature representation and gradient flow in the PP-LCNet backbone.

- Inference Acceleration via EOS Termination. We introduce an end-of-sequence (EOS) token that enables early stopping during decoding, eliminating redundant computation caused by SLANet’s fixed maximum sequence length.

- Progressive Multi-Phase Training Strategy. We design a progressive three-phase training scheme, coarse learning, fine-tuning, and high-resolution refinement, to stabilize convergence and enhance structural sequence modeling. This staged curriculum provides a more effective optimization path than a single fixed learning rate.

2. Related Work

2.1. Heuristic-Based Table Structure Recognition

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Table Structure Recognition

3. Methodology

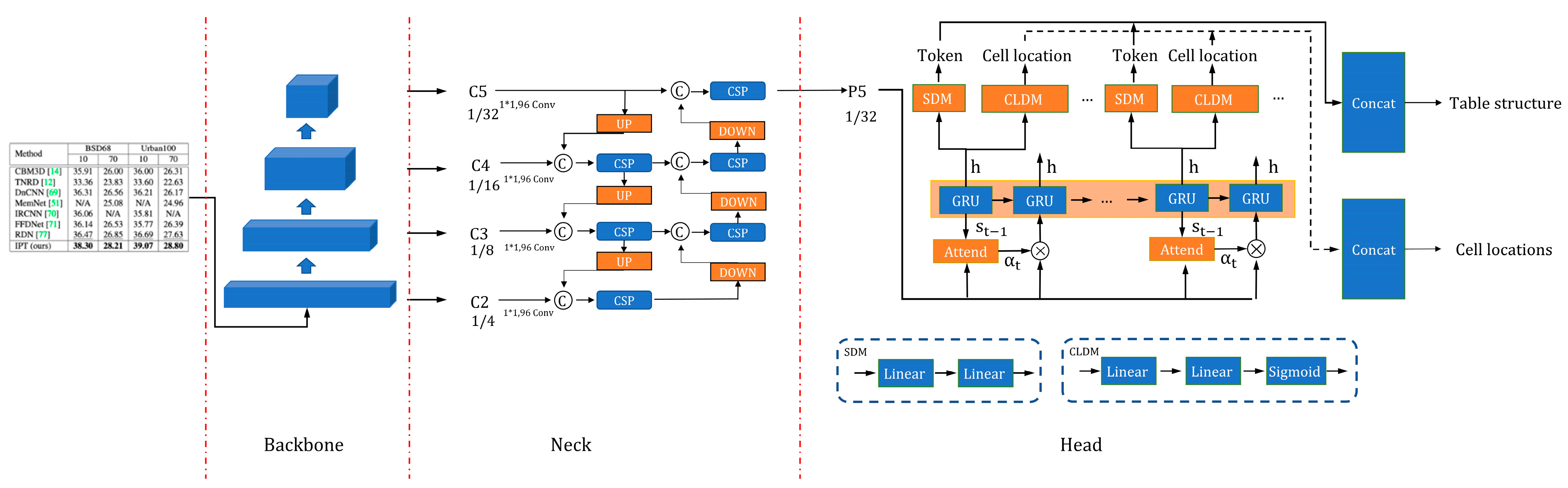

3.1. Baseline SLANet

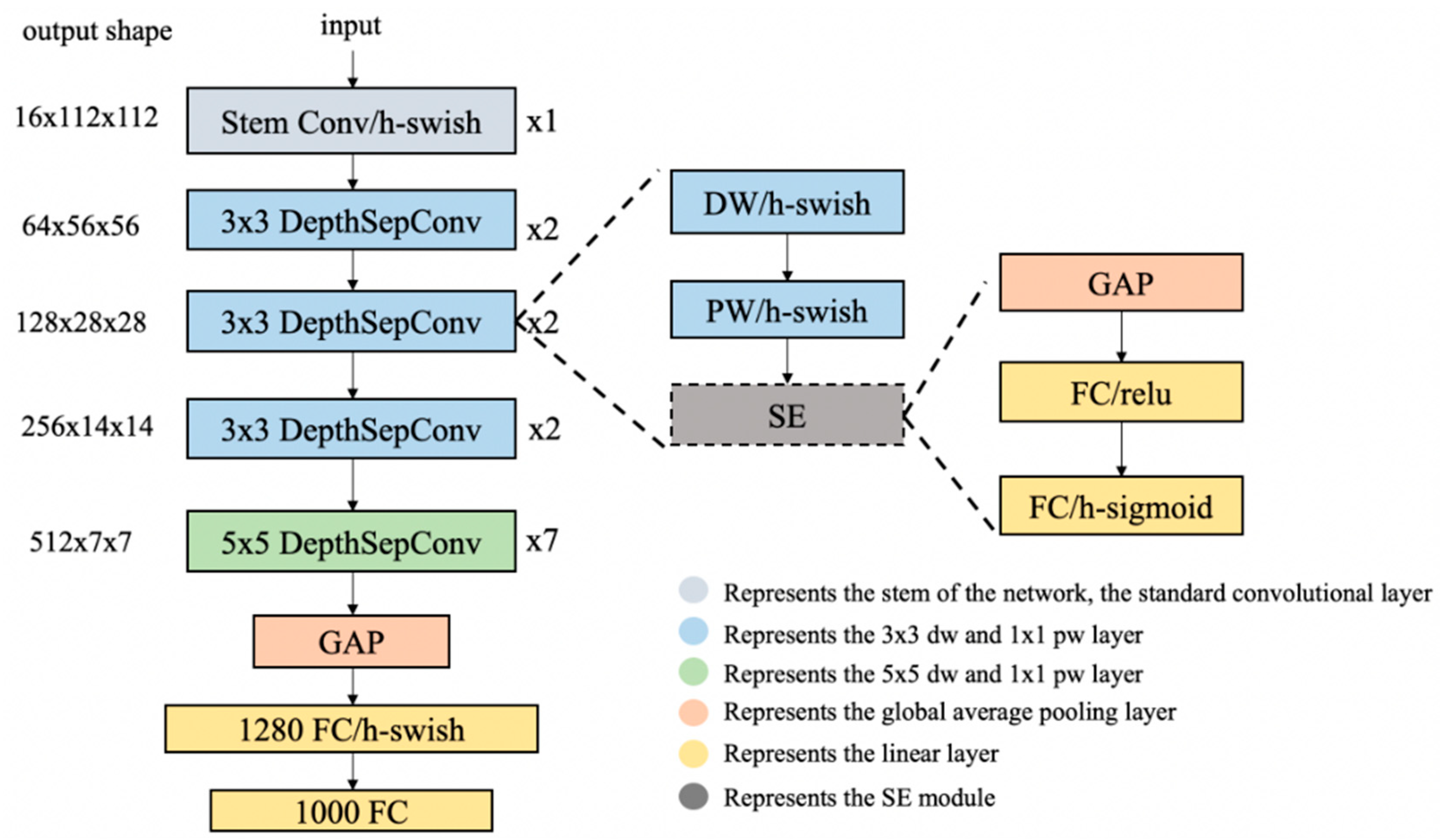

- employing more effective activation functions,

- selectively inserting squeeze-and-excitation (SE) modules,

- introducing larger convolution kernels at appropriate positions, and

- utilizing a larger 1 × 1 convolution layer after the global average pooling layer.

3.2. Activation Function Optimization

3.3. EOS-Based Inference Optimization

| Algorithm 1. Decoding loop with EOS termination strategy |

| Input: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Output: |

|

|

| 1. Initialize |

| 2. For t = 1 to Lmax do: |

| 3. // Decode step |

| 4. |

| 5. // Select the token with the highest probability |

| 6. |

| 7. // Store predictions |

| 8. Append |

| 9. Append |

| 10. Append |

| 11. // EOS Termination Check (Optimization) |

| 12. If EOS exists in the history of all samples in the batch then: |

| 13. Break Loop |

| 14. // Update input for the next time step |

| 15. |

| 16. End For |

| 17. Return |

| Algorithm 2. Original decoding loop in SLANet |

| Input: |

|

|

|

|

| Output: |

|

|

| 1. Initialize |

| 2. For t = 1 to Lmax do: |

| 3. // Decode step |

| 4. |

| 5. // Select the token with the highest probability |

| 6. |

| 7. // Store predictions regardless of completion |

| 8. Append |

| 9. Append |

| 10. // Update input for the next time step |

| 11. |

| 12. End For |

| 13. Return |

3.4. Progressive Multi-Phase Training Strategy

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Environment

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

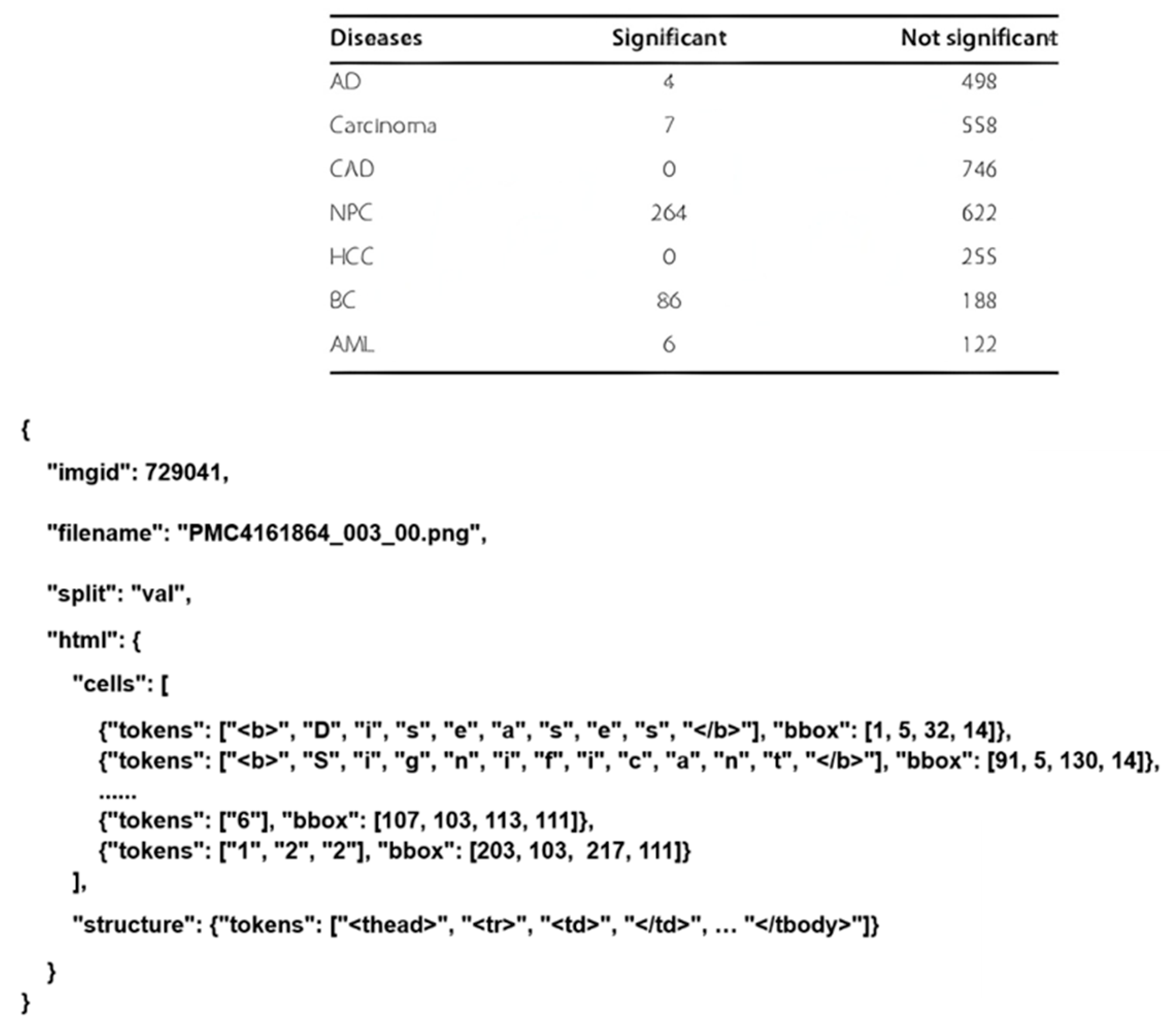

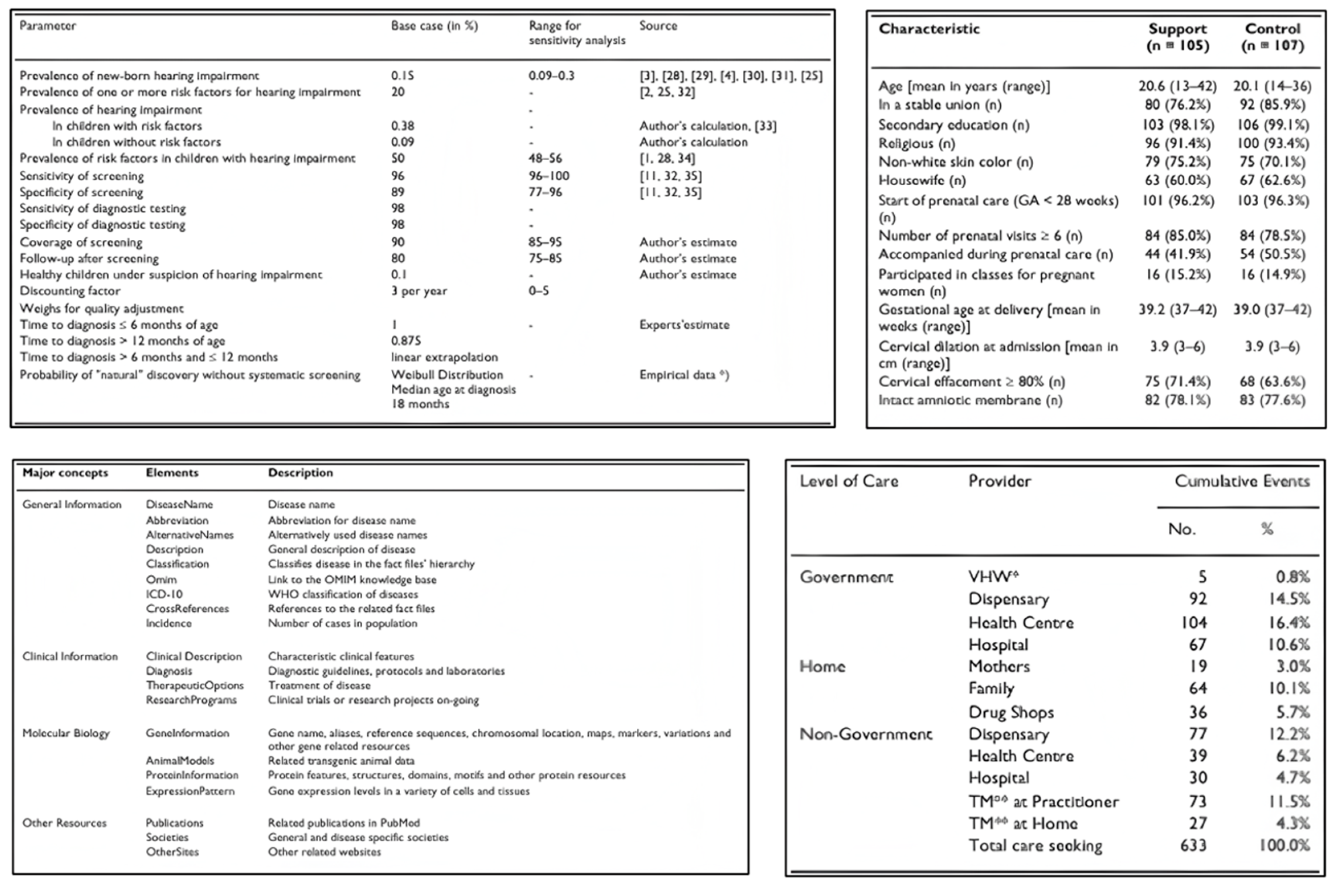

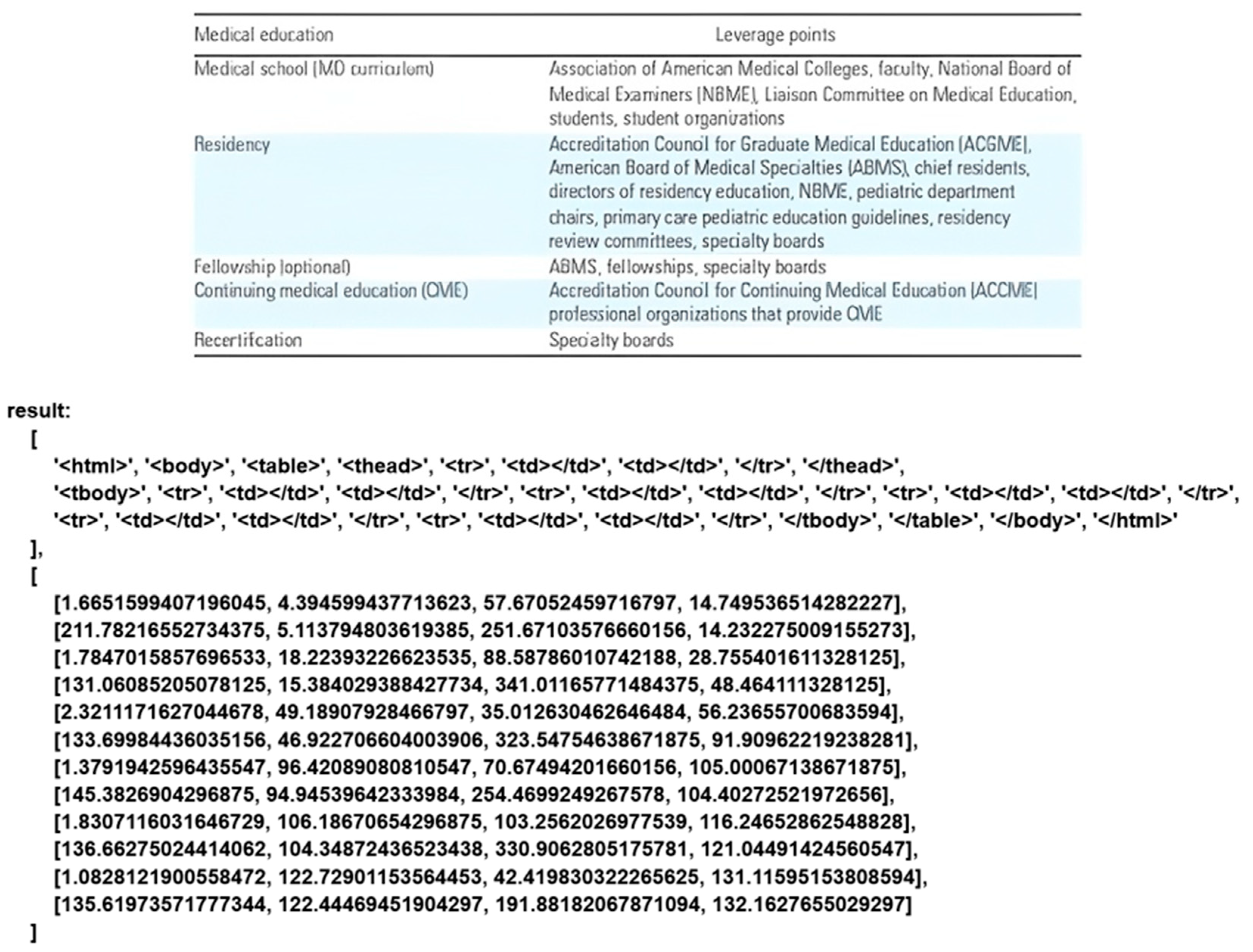

4.3. Dataset

4.4. Experimental Results and Ablation Study

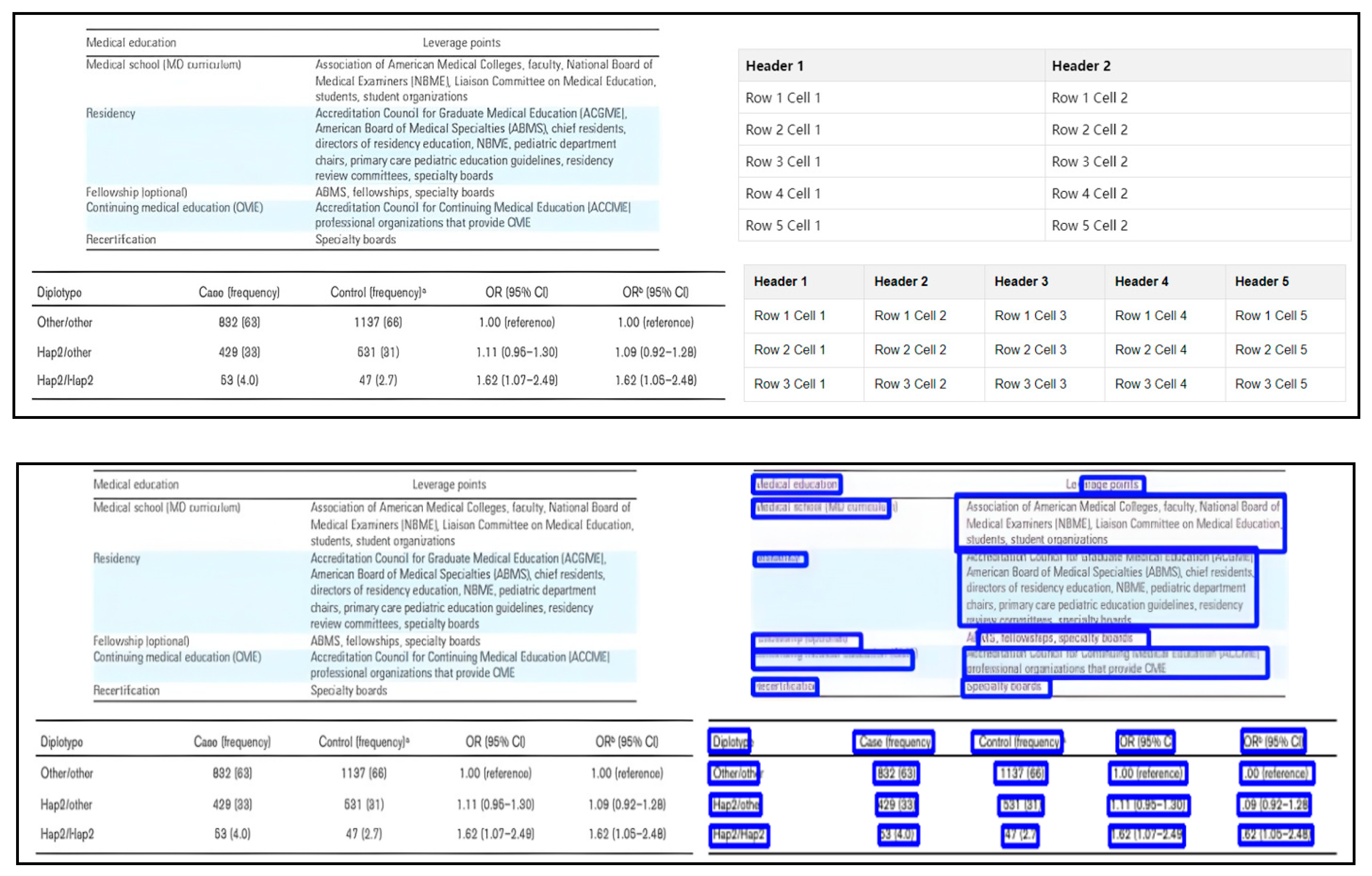

4.5. Qualitative Results

4.6. Limitation and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kasem, M.S.; Mahmoud, M.; Yagoub, B.; Senussi, M.F.; Abdalla, M.; Kang, H.S. HTTD: A Hierarchical Transformer for Accurate Table Detection in Document Images. Mathematics 2025, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; ShafieiBavani, E.; Jimeno Yepes, A. Image-based table recognition: Data, model, and evaluation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 564–580. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.; Xiao, B.; Simsek, M.; Kantarci, B.; Khan, S.; Alkheir, A.A. TableStrRec: Framework for table structure recognition in data sheet images. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recognit. 2024, 27, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, M.; Abdallah, A.; Berendeyev, A.; Elkady, E.; Mahmoud, M.; Abdalla, M.; Taj-Eddin, I. Deep Learning for Table Detection and Structure Recognition: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Wang, J. TABLET: Table Structure Recognition using Encoder-only Transformers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR) 2025, Wuhan, China, 16–21 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Guo, R.; Zhou, J.; An, M.; Du, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Yu, D. Pp-structurev2: A stronger document analysis system. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.05391. [Google Scholar]

- Itonori, K. Table structure recognition based on textblock arrangement and ruled line position. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Tsukuba, Japan, 20–22 October 1993; pp. 765–768. [Google Scholar]

- Rahgozar, M.A.; Fan, Z.; Rainero, E.V. Tabular document recognition. In Document Recognition; SPIE: St Bellingham, WA, USA, 1994; Volume 2181, pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama, Y. A method for table structure analysis using DP matching. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995; Volume 2, pp. 583–586. [Google Scholar]

- Zuyev, K. Table image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Ulm, Germany, 18–20 August 1997; Volume 2, pp. 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Kieninger, T.G. Table structure recognition based on robust block segmentation. In Document recognition V; SPIE: St Bellingham, WA, USA, 1998; Volume 3305, pp. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kieninger, T.; Dengel, A. Applying the T-RECS table recognition system to the business letter domain. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 September 2001; pp. 518–522. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Phillips, I.T.; Haralick, R.M. Table structure understanding and its performance evaluation. Pattern Recognit. 2004, 37, 1479–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishitani, Y.; Fume, K.; Sumita, K. Table structure analysis based on cell classification and cell modification for xml document transformation. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 31 August–1 September 2005; pp. 1247–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.-F.; Qu, H.-R.; Su, W.-H. From sensors to insights: Technological trends in image-based high-throughput plant phenotyping. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-F.; Qin, Y.-M.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Xu, M.; Schardong, I.B.; Cui, K. RA-CottNet: A Real-Time High-Precision Deep Learning Model for Cotton Boll and Flower Recognition. AI 2025, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yan, C.; Wang, H.; Xie, X. ROS-SAM: High-Quality Interactive Segmentation for Remote Sensing Moving Object. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X.; Li, N.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Hancock, E.R. Attribute subspaces for zero-shot learning. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 144, 109869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Bai, X.; Huang, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhou, J.; Harada, T. Goal-Oriented Gaze Estimation for Zero-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3794–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Tupaj, S.; Shi, Z.; Chang, C.H.; Alam, H. Extracting Tabular Information from Text Files; EECS Department, Tufts University: Medford, OR, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Cui, L.; Huang, S.; Wei, F.; Zhou, M.; Li, Z. Tablebank: Table benchmark for image-based table detection and recognition. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; pp. 1918–1925. [Google Scholar]

- Long, R.; Wang, W.; Xue, N.; Gao, F.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, G.S. Parsing table structures in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 944–952. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, K.A.; Liwicki, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.A.; Afzal, M.A.; Afzal, M.Z. Current status and performance analysis of table recognition in document images with deep neural networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 87663–87685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tensmeyer, C.; Morariu, V.I.; Price, B.; Cohen, S.; Martinez, T. Deep splitting and merging for table structure decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, S.; Agne, S.; Wolf, I.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. Deepdesrt: Deep learning for detection and structure recognition of tables in document images. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Kyoto, Japan, 9–12 November 2017; Volume 1, pp. 1162–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Fateh, I.A.; Rizvi, S.T.R.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. Deeptabstr: Deep learning based table structure recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 1403–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal, S.S.; Vishwanath, D.; Rahul, R.; Sharma, M.; Vig, L. Tablenet: Deep learning model for end-to-end table detection and tabular data extraction from scanned document images. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.; Khalid, S.M.D.; Shahzad, M.A.; Shafait, F. Table structure extraction with bi-directional gated recurrent unit networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 1366–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Li, Q.; Tao, D. Res2tim: Reconstruct syntactic structures from table images. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 749–755. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Yu, B.; Wang, W.; Tao, D.; Li, Q. Tgrnet: A table graph reconstruction network for table structure recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 1295–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, H.; Gao, F.; Long, R.; Bu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Li, L.; Yao, C.; Yu, Z. LORE: Logical location regression network for table structure recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 2992–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Yan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, F.; Liu, X. GFTE: Graph-based financial table extraction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Virtual Event, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 644–658. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Rosenberg, D.; Mann, G. Challenges in end-to-end neural scientific table recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 894–901. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Kanervisto, A.; Ling, J.; Rush, A.M. Image-to-markup generation with coarse-to-fine attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 980–989. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Qi, X.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, D.; Gao, P.; Xiao, R. Pingan-vcgroup’s solution for icdar 2021 competition on scientific literature parsing task b: Table recognition to html. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.01848. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, N.; Yu, W.; Qi, X.; Chen, Y.; Gong, P.; Xiao, R.; Bai, X. Master: Multi-aspect non-local network for scene text recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 117, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PaddlePaddle. PaddleOCR: PP-Structure Table. Available online: https://github.com/PaddlePaddle/PaddleOCR/tree/release/2.5/ppstructure/table (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Qiao, L.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Pu, S.; Niu, Y.; Ren, W.; Tan, W.; Wu, F. Lgpma: Complicated table structure recognition with local and global pyramid mask alignment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Lausanne, Switzerland, 5–10 September 2021; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

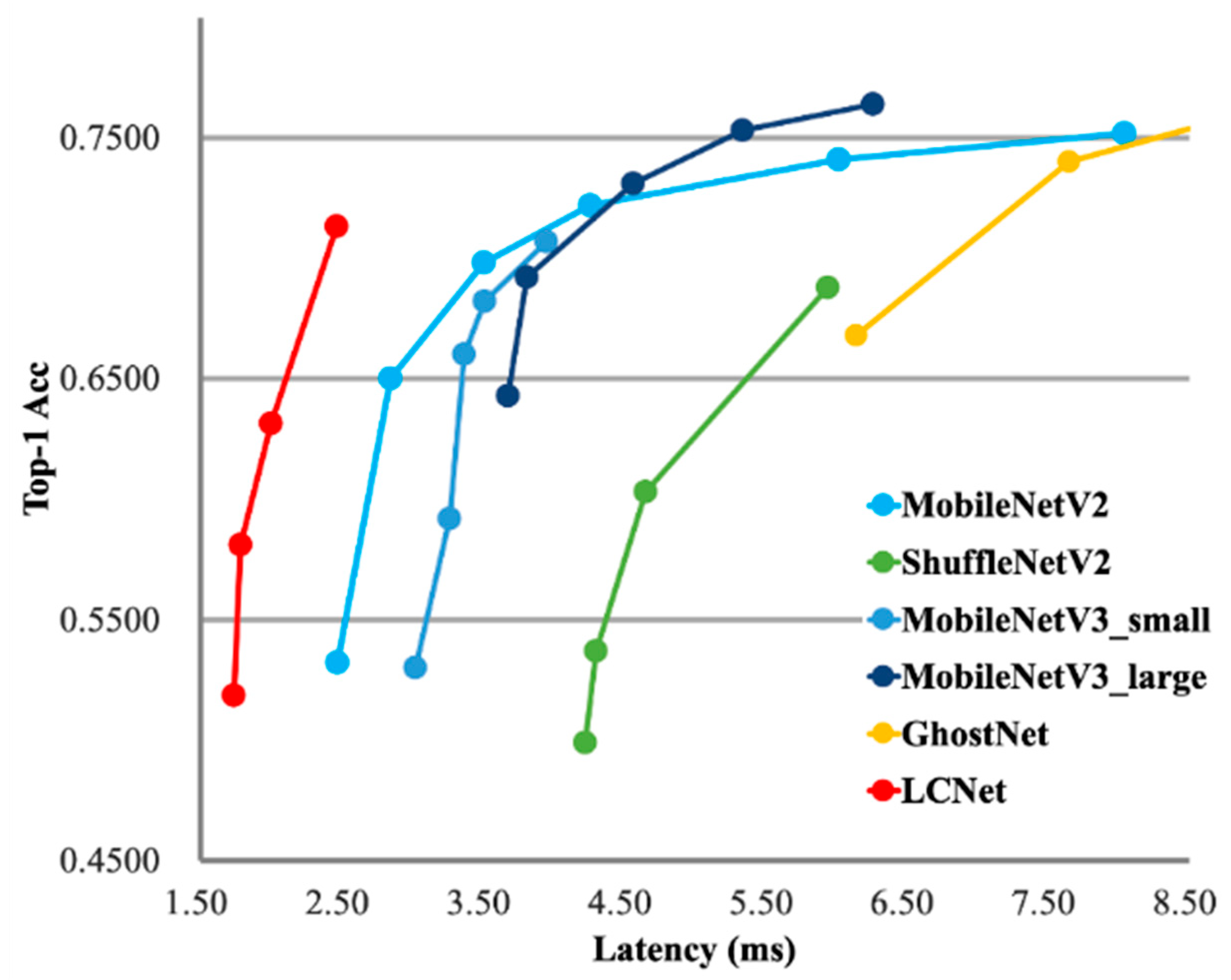

- Cui, C.; Gao, T.; Wei, S.; Du, Y.; Guo, R.; Dong, S.; Lu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, Q.; et al. PP-LCNet: A lightweight CPU convolutional neural network. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

| Approach | Representative Methods | Main Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heuristic-based | T-Recs [11], Wang et al. [13] | No training data needed; interpretable. | Lacks robustness; fails on complex/irregular layouts; requires handcrafted rules. |

| Detection/Segmentation | DeepDeSRT [25], TableNet [28] | Visual intuition; good for row/col extraction. | Post-processing is complex; struggles with spanning cells and empty cells. |

| Logical Location | LORE [33], TGRNet [31] | Direct coordinate regression. | High computational cost for graph construction; difficulty fusing multimodal features. |

| Image-to-Sequence | SLANet [6], TABLET [5] | End-to-end; outputs editable code (HTML). | Heavy models (e.g., TABLET) are slow; Light models (e.g., SLANet) lack accuracy. |

| Activation Function | Accuracy (%) | Inference Time (mS) |

|---|---|---|

| H-Swish | 75.99 ± 0.49 | 766 |

| Swish | 76.52 ± 0.53 | 810 |

| Mish | 77.04 ± 0.69 | 850 |

| Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | Inference Time (MS) | TEDS (%) | TEDS-Struct (%) | Model Size (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGPMA | 65.74 | 1654 | 94.70 | 96.70 | 177 |

| TABLEREC-RARE | 71.73 | 779 | 93.88 | 95.96 | 6.8 |

| SLANET | 75.99 | 766 | 95.74 | 97.01 | 9.2 |

| TABLET | 89.22 | 1521 | 96.79 | 97.67 | 45.5 |

| OURS | 77.25 | 774 | 96.67 | 97.83 | 9.6 |

| Strategy | Accuracy (%) | Inference Time (MS) | Model Size (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLANET | 75.99 | 766 | 9.2 |

| +MISH | 76.98 | 850 | 9.6 |

| +EOS | 77.01 | 745 | 9.6 |

| +T_STAGE | 77.25 | 774 | 9.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mao, L.; Xiao, Y.; Du, K.; Shen, J.; Xie, X. Lightweight and Accurate Table Recognition via Improved SLANet with Multi-Phase Training Strategy. Mathematics 2026, 14, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010025

Mao L, Xiao Y, Du K, Shen J, Xie X. Lightweight and Accurate Table Recognition via Improved SLANet with Multi-Phase Training Strategy. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Liu, Yujie Xiao, Kaihang Du, Jie Shen, and Xia Xie. 2026. "Lightweight and Accurate Table Recognition via Improved SLANet with Multi-Phase Training Strategy" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010025

APA StyleMao, L., Xiao, Y., Du, K., Shen, J., & Xie, X. (2026). Lightweight and Accurate Table Recognition via Improved SLANet with Multi-Phase Training Strategy. Mathematics, 14(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010025