1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) uses neural networks to train computers in the same way as the human brain. In recent years, we have witnessed the development of digital technologies that have been used to collect multidimensional big data. This makes it necessary to obtain new methods for modeling and analysis. The modification of theoretical algorithms is very important for this practice, together with its effective application in different sciences.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) are a special type of neural network that incorporates physics laws into the learning process. They differ from traditional neural networks because PINNs connect domain-specific knowledge to physical principles to increase their predictive capabilities in engineering and scientific contexts. PINNs combine data-driven learning with physics laws and, in this way, they offer a robust tool for solving very complex partial differential equations (PDEs) and ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that arise in mathematical physics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In this context, PINNs are very good at accurately modeling different physics phenomena like fluid dynamics, predicting material characteristics, and solving inverse problems [

2,

6].

As is well known, different physics phenomena are described by different mathematical models and therefore by different nonlinear Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) in general. The corresponding solutions can differ from each other in their structure, their behavior at infinity, etc. We are looking for traveling wave solutions and aiming to draw their profiles as well as to construct appropriate solutions with special physical meaning in laser optics and fluid dynamics. As in many cases, these equations are modeling waves that have different geometrical structures (traveling waves, kinks, solitons, loops, butterflies, ovals, peakons and anti-peakons, among others). We provide in this paper two equations—the Boussinesq Paradigm equation and b-equation—as typical examples of PDEs that have solutions in a special form such as solitons, kinks, and peakons. Special attention is paid to the interactions of two solitons and to the interactions of peakons–kinks by reducing the original equations to the study of a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with a non-smooth right-hand side. In this way, we are able, in some cases, to obtain global first integrals of these systems and to study the interaction of the waves using methods from classical analysis. This is the novelty of the analytical results obtained in this paper.

In this paper, firstly, we shall study the Cauchy problem for the Boussinesq Paradigm equation [

7,

8] as follows:

where

,

,

,

as

The variable

states for a surface elevation,

,

,

,

,

, present two dispersive coefficients and

presents an amplitude parameter. Equation (

1) can be derived by modeling the surface waves in shallow waters. It can also be found in other different fields such as the theory of acoustic waves, in ion-sound waves, plasma and nonlinear lattice waves, etc. [

8].

The dispersive multidimensional Boussinesq equation [

7,

8] and its generalizations—for instance, the

Boussinesq equation and the Boussinesq Paradigm equation—arise mainly in fluid mechanics via the formation of patterns in liquid drops, the vibrations of a single one-dimensional lattice, etc. In the literature [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] there are many developments concerning the Boussinesq equation and its generalizations. A detailed study of the Boussinesq Paradigm Equation (

1) from the point of view of the traveling wave solutions can be found in

Section 3 below. We obtain the solutions in integral form. Moreover, the solitons develop cusp-type singularities and we study the interactions of two solitons as well.

This paper will deal with the interactions of peakon, anti-peakon, and peakon—kink solutions for the generalization of the b-equation [

13], namely an evolution PDE containing both quadratic and cubic nonlinearities:

,

,

are some constants.

When

,

,

, we obtain the Camassa–Holm equation, and when

,

, we have the cubic nonlinear evolution equation [

9]. Usually, when studying the interactions of (anti)peakons and kink waves, we look for solutions of (2) in a special form which we call Ansatz. In this way, we reduce the equation to a system of ODE with jumps because of the non-smooth right-hand side. Then, we obtain global first integrals. Applying some restrictions, we can solve the obtained ODE in quadratures or in special elementary functions—elliptic ones. We shall find the solutions in explicit form and we shall study their interactions using classical analytical methods. A geometrical interpretation of the collision of this kind of waves is given in

Figure 1.

In this paper, we shall study Equations (1) and (2) by applying a new methodology, namely Physics-Informed Cellular Neural Networks (PICNNs). In this way, we will be able to obtain soliton solutions of (1) and peakon-kink solutions of (2). We shall develop an artificial intelligence algorithm based on PICNNs for the interactions of soliton and peakon-kinks waves which arise from Equations (1) and (2). The algorithm for obtaining soliton and peakon-kink solutions and their interactions will be presented in detail in

Section 5.

We shall present a brief comparison with other investigations in the field of PINNs. Raissi et al. [

4,

5] used Gaussian process regression to construct representations of a linear operator functional, accurately derive the solution, and provide uncertainty estimates for various physical problems. This study was then extended in [

6]. Various articles have been published in which the new concepts of PINNs are presented. For example, researchers have previously addressed the potential, limitations, and applications of straight and inverse problems for three-dimensional flows [

1] or comparison with other machine learning techniques. An introduction to PINNs that covers the basics of machine learning and neural networks can be found in the work of Kolmansberger et al. [

2]. In the literature, PINNs are also compared with other methods that can be applied to solve PDEs, such as the one based on the Feynman–Katz theorem [

3]. Finally, PINN codes have been extended to solve integro-differential equations or stochastic differential equations. In Ref. [

14], a bilinear neural network method for solving nonlinear PDE is presented. In Ref. [

15], Lax pairs-informed neural networks (LPNNs) for finding wave solutions are provided. To the authors’ knowledge, cellular neural networks have not previously been incorporated into PINNs’ architecture. This is the novelty of the obtained AI algorithm in this paper.

This paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce Physics-Informed Neural Networks.

Section 3 deals with some analytical results related to Equation (

1), as well as the interactions of soliton waves which arise. In

Section 4, we obtain analytically the interaction of peak (antipeak)-kink solitons. In

Section 5, we develop the concept of Physics-Informed Cellular Neural Networks and apply them to study the models under consideration. We develop an artificial intelligence algorithm based on PICNNs. The obtained results will be presented numerically by computer simulations using the NVIDIA package [

16].

2. Physics-Informed Neural Networks

Introduced in 2017 in the papers [

4,

5] and then in 2019 [

6], PINNs are a new class of neural networks which can solve nonlinear partial differential equations. Raisi et al. present PINNs as a new method for finding solutions to the Allen–Cohn, Schrödinger, and Burgers equations. In these papers, they show that PINNs are able to handle two problems—forward and inverse problems. For solving forward problems they illustrate how to evaluate the solutions of the governing equations, while in the inverse problems the parameters of the models are obtained though learning process from the observation data. Since the introduction of PINNs, many papers have been published which present new concepts for solving different types of equations [

1,

2,

3,

14,

15]. In these papers, the potential and applications of PINNs in both forward and inverse problems, as well as a comparison with existing machine learning algorithms, are described. In Ref. [

2], Kolmansberger et al. present an introductory course on PINNs. Also, PINNs are compared with different methods for solving differential equations. The PINN approach has been applied to various types of differential equations, such as integro-differential equations, stochastic differential equations, etc.

In

Figure 2, we present the scheme of the main blocks of PINN architecture:

There are three main blocks—including neural networks and PINNs which, through automatic differentiation, incorporate the governing differential equations and loss function minimization block.

Let us consider a general type of partial differential equation written in the following form,

where the solution is

,

x is the space variable in the one-dimensional domain

and

is a physical parameter which takes different values in

. If we have parametric problems then

can be considered as the second variable, while for inverse problems it is unknown. We can add boundary conditions (BCs) and initial conditions (ICs) for the forward problems, unless, for the inverse problems, additional conditions should be added, such as, for example, the known solution at some values of

x.

We shall introduce vector

for all unknown parameters of the deep neural network for both forward and inverse problems, and

in the case of inverse problems. Therefore, the neural network should learn to approximate the governing differential equations by finding

, which is obtained by minimizing the loss function depending on the differential equation

, the boundary conditions

, and some known data

, all of which are weighted:

Usually, in the PINN approach, the loss function

can be defined as follows:

where the residual equation is evaluated as a set of

points denoted as

. These points are called collocation points. When we add the boundary data in the training data set, the neural network is able to learn to approximate the solution at the boundaries where the known solutions are available. Therefore, PINNs can solve PDE in inverse problems in a data-driven manner.

PINNs have many advantages in comparison to traditional numerical methods. One of these advantages is numerical simplicity; in PINNs, we do not need discretization as we do in finite-difference methods. Moreover, the number of the collocation points is not high in order to guarantee the convergence of the training process. Another advantage is that after the training is complete, the solution is predicted on any other grid different from the collocation grid, which is not the same as the traditional numerical methods where additional interpolation is needed.

3. Analytical Results Concerning Equation (1)

In this section, we shall present some analytical results concerning the Cauchy problem for the Boussinesq Paradigm Equation (

1). Let us put in Equation (

1)

,

. We shall look for traveling waves solutions of the form

,

,

. We shall integrate (1) in

two times and we shall take the integration constants equal to zero. So, we obtain

i.e.,

Below, we shall illustrate the

method [

8]. For this purpose, we put

with

,

,

as unknown parameters.

Now, we shall substitute (8) in (7). It is known that the function

and it can be seen that

satisfies the ODE

. Therefore, for

, we get

i.e.,

Then,

So, we obtain

which, in fact, generates a traveling wave solution

of (1),

.

In (11),

,

. Consequently,

,

,

It is possible to obtain (11) using the fact that for

, i.e.,

and evidently

,

, etc.

Now, we shall study the problem of the interaction of solitary waves which satisfy the 1D version of (1) with , , and , .

In [

7], it is shown that (1) has the traveling wave solution, represented by solitons

or . The maximum of is attained at the line .

We shall investigate the Cauchy problem for (1) with initial data

Equation (

1) is nonlinear PDE and therefore

in the general case.

We shall apply a new conservative finite difference scheme for (1) and we shall consider two cases:

Case (i). , , , , , , , .

Therefore,

and

are two solitons which move in opposite directions. At some point, they collide and a new wave arises. This wave is weaker than the initial waves in the sense that its amplitude is smaller. In time, the initial two solitons increase and continue to travel with the same shapes as they had before the collision (see

Figure 3):

Case (ii). , , , , , ,

In this case, the soliton blows up after the collision and the absolute value of the amplitude increases. The blow-up time .

4. Interaction of Kink-Peakon Solutions to the B-Equation (2)

We shall apply the following Ansatz of the solution to the b-equation [

13]:

In [

13], it is proved that when

and

is arbitrary, the amplitudes

and the position functions

must satisfy the system of an ODE of the following type:

In the case when we have an interaction of a single kink and

N-peakons, the Ansatz for the solution

v is similar to (14) (when

,

):

In Formula (16)

,

. In this case, the ODEs which are satisfied by

,

,

are very complicated and we shall omit their formulation (see [

13]).

Let us assume that in (15),

. Put

,

. Therefore, (15) takes the form

From the first two equations, we obtain

and from the second and the third equations, we get

where

.

We shall make the following change

. In this way,

and the function

is unknown,

. Then, (19) takes the following form

Equation (

20) is a linear ODE with respect to the unknown function

and the independent variable

, so

Therefore, we obtain

and certainly

is a first integral of (17). Let

. We shall find

as a solution of the ODE

, and therefore

We shall study the zeroes of the cubic polynomial . If has three simple zeroes , , then the integral , is real. In the case when has one simple zero and two complex-valued zeros then is a logarithm of the second order of the non-vanishing polynomial of , which is multiplied by of a linear function of . Since the inversion of the function is non-explicit, it is better to work with definite integrals such as, for example, , etc.

The system (17) can be solved as and .

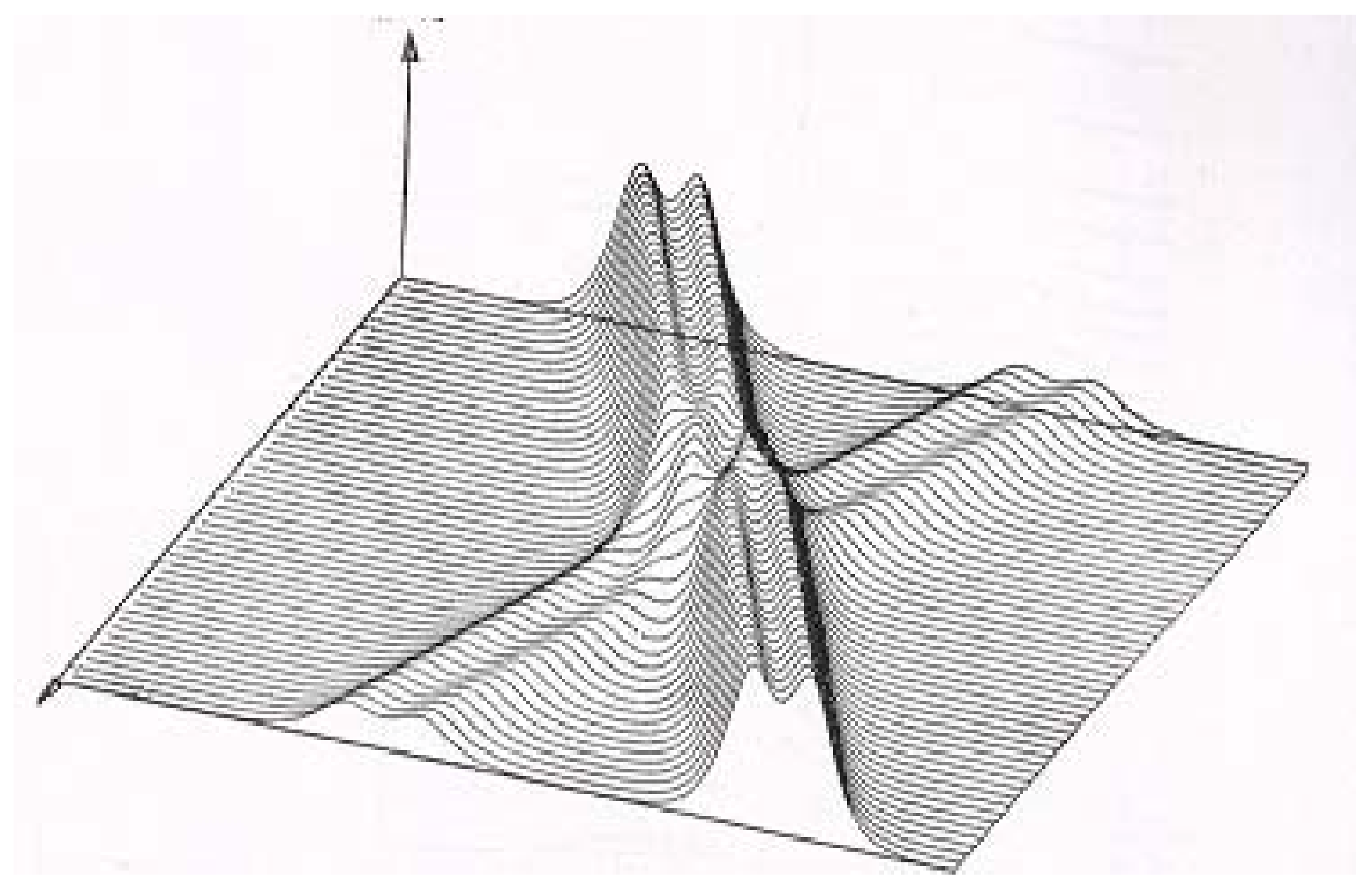

A qualitative picture of the interaction between kink and peakon waves, which is described by the b-Equation (

2), is given in

Figure 4.

5. A Physics-Informed Cellular Neural Networks Algorithm for Studying Interactions Between Solitons and Rock Waves

In [

17], it is shown that some autonomous cellular neural networks (CNNs) represent accurate approximations of the nonlinear partial differential equations. This is possible because the CNN solutions of nonlinear PDE are continuous in time, discrete in space, continuous in parameters, and continuously bounded in value.

In

Figure 5, the architecture of a 2D grid of CNNs is presented. The squares are the cells

. All cells are identical. The structure of a single cell is given in the figure—it consists of a feedback template, a control template, bias, and cell input and output. The interaction of each cell with its neighbor cells is obtained through feedback from other cells. Usually the cells are nonlinear dynamical systems. The interaction between cells is linear, which means that the spatial structure of CNNs is linear and for this reason they are very suitable for solving physics and engineering problems.

In [

17,

18], the state equation of CNN is described by:

where

is the state variable,

is the output of the CNN,

is the one-dimensional Laplace template,

is the one-dimensional nonlinear Laplace template, ∗ is the convolution operator defined in [

18], and

is a bias.

In this paper, we develop a new AI algorithm for solving nonlinear PDE–Physics-Informed Cellular Neural Networks (PICNNs). PICNNs are able to approximate the solutions of nonlinear PDEs with very high accuracy in real time. We shall find the loss function of PICNNs in the following integral form:

where

is the approximate solution of the PDE (3) and function

defines the problem’s data. This formulation is necessary for both the theoretical study and for the implementation of PICNNs. During the training of PICNNs, the network parameters

are recovered.

During numerical analysis, usually we approximate the solution

of the PDE (3) with the algorithm which computes

. The estimation of the global error is the main problem of the algorithms. Here, we propose the following global error estimation:

We are looking for a set of parameters,

, such that

.

In the process of numerical discretization, the most important are the stability, consistency, and convergence of the algorithm. Therefore, the discretization error is found in terms of consistency and stability, which is a basic aspect of study in numerical analysis. In PICNNs, the convergence and stability of the algorithm are estimated with the learning process of neural networks connected to data and physical principles.

In [

19], the authors present a neural network which has a

activation function and only two hidden layers, where

is considered. In this way, the authors find the function

v with a bound in a Sobolev space:

where

N is the number of training points,

are known constants which are independent of

N, and

v belongs to the Sobolev space

W.

In order to validate the accuracy of predictions made by PICNNs, we compute the relative

error between the predicted

solution and the exact

solution by the following formula [

20]:

where

are the collocation points in the spatial–temporal domain.

In this paper, we develop a new AI algorithm for training PICNNs in the following way:

Input BC and IC, Collocation points for coordinates.

1. Perform initialization of the iterations .

2. Non-dimensionalize the Boussinesq Paradigm Equation (

1) (b-Equation (

2), respectively).

3. Present the solution of (1) (respectively (2)) by cellular neural network .

4. Use the activation function and initialize the cellular neural network.

5. Train PICNNs with the minimum total loss function

6. Update the model parameters:

7. If then

(i) Save the model parameters.

(ii) Update the minimum loss

(iii) Initialize the counter.

If the termination criterion is satisfied, then stop the training loop.

Otherwise, increase the counter.

End of algorithm.

Applying the above PICNN algorithm using Python 3.8 on a computer equipped with NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 graphics card from the NVIDIA Corporation [

16], we obtain the following results:

In

Figure 6, using a PICNN, we identify the interaction of two solitons

and

of the Boussinesq Paradigm Equation (

1) with the following parameters

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

. We apply a four-layer CNN with 80 neurons each. The network is trained with 20,000 iterations followed by 20,000 steps on a spatial–temporal domain. The resulting relative

error is found to be

. The solitons move in opposite directions and when they collide, a new weaker wave arises. The initial two solitons continue to travel after the collision with the same shape.

In

Figure 7, the results obtained by PICNNs present the interaction of peakon-kink waves in the case

and

. The CNN architecture consists of five layers with 80 neurons each. The training of the network is provided by 20,000 iterations and the relative

error is calculated

.

The main advantage of the PICNN algorithms is that they are very fast. This is due to the spatial structure of the CNN. Another advantage is that we obtain the solutions in real time. For the boundary conditions, we shall use Dirichlet boundary conditions. Usually, PICNN are mesh-free and they allow the computation of the solutions after a training stage. Moreover, PICNNs make the solutions differentiable by applying an analytical gradient. By using the same optimization problem, PICNNs can solve both forward and inverse problems.

6. Discussion

PICNNs have many advantages, but they still have limitations and challenges. Here, we shall discuss some of the constraints and challenges connected to the applications of PICNN algorithms. These include the complexity of the computations, data scarcity, automatic differentiation of the complex mathematical physics equations, as well as robustness and some generalizations.

In this discussion, we shall comment on some of the potential future research on PICNN which can lead to the advancement of the field. This could include, for instance, novel AI algorithms for training neural networks, as well as improving the efficiency of the algorithms. In particular, interdisciplinary collaborations are very helpful for exchanging ideas about problem solving, optimizing the stability and convergence of the algorithms, etc. The connection between physics and machine learning can lead to in-depth investigations of relevant problems and optimization of the algorithms. The link between engineering and data science contributes to specific knowledge in fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, and feature engineering. PICNN algorithms contribute to materials science by optimizing new materials and contribute to robotics and nanotechnology by enhancing autonomous system and control techniques.

In conclusion, the interdisciplinary property of PICNN algorithms significantly improves reliability and model transparency, solving real-world problems. The full potential of PICNNs focused on these applications may address very complex problems because it can simplify our understanding of the models with regard to physics and data relationships. In this way, PICNNs can contribute to scientific discovery and innovative AI engineering tools.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we developed a new AI algorithm for studying the interactions between solitons and peakons-kinks based on Physics-Informed Cellular Neural Networks (PICNNs). These kinds of waves arise from the Boussinesq Paradigm equation and the b-equation, respectively. We presented some analytical results for the two equations under consideration. Usually, such equations arise in fluid mechanics.

We presented a short overview of Physics-Informed Neural Networks. Then, we introduced PICNNs which were able to present solutions to nonlinear PDEs in real time. We developed an AI algorithm based on PICNNs and presented simulations created using the NVIDIA package. The computer simulations illustrated the theoretical results in the paper. The AI algorithm has many advantages, such as fast approximations due to automatic differentiation, real-time solutions, the simplicity of the algorithm, etc. In future work, this algorithm can be applied for solving different problems in the fields of quantum mechanics and materials science.