An Age-Distributed Immuno-Epidemiological Model with Information-Based Vaccination Decision

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Propose an age-distributed epidemic model with information-based vaccination decisions. This study continues the previous works on epidemic models that involve time-since-infection distributed recovery rates and death rates [11,26,58]. This approach allows us to take into account time-dependent recovery and death rates which give a more accurate understanding of epidemic progression than the conventional SIR models.

- Establish the existence and uniqueness of a positive solution for the proposed age-distributed model.

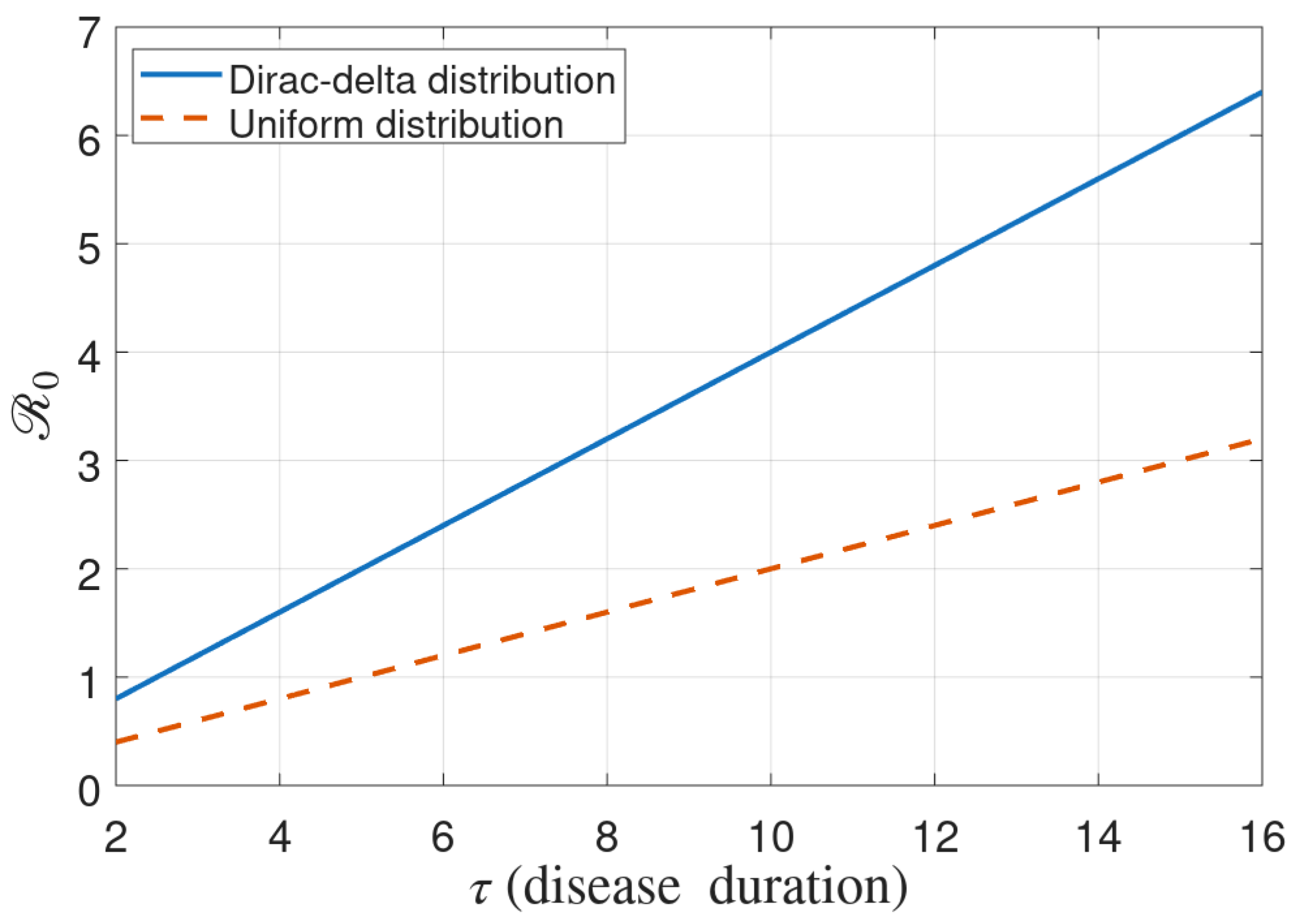

- For the age-independent version of the proposed model, derive the analytical expression of under different choices of recovery and death distributions and determine the bounds for the final size of the epidemic.

- Conduct extensive numerical simulations to explore the effects of various parameters involved in information-based vaccination decisions, such as the impact of the memory kernel and the baseline probability of vaccination.

2. Model Formulation

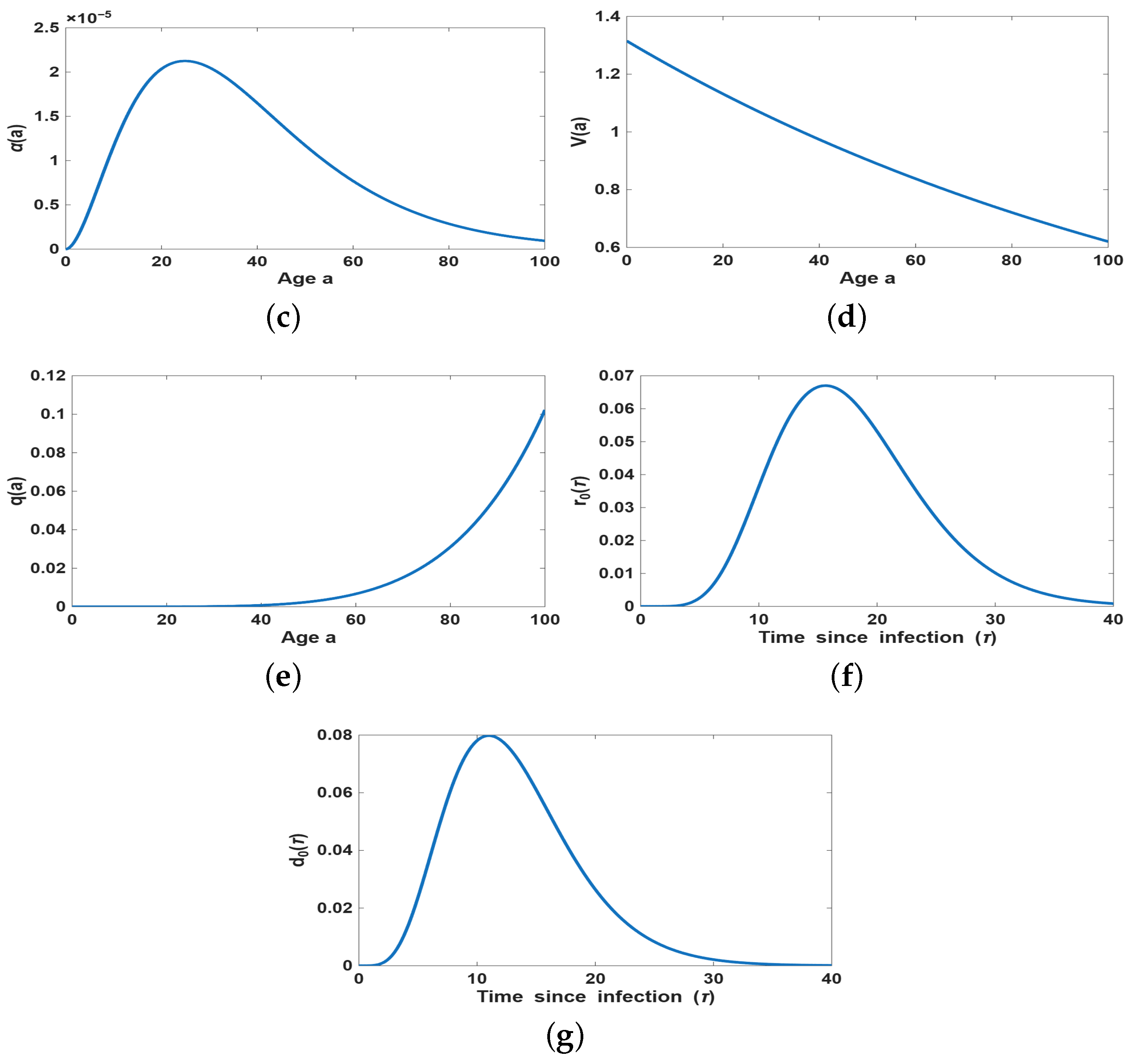

2.1. Distributed Recovery and Death Rates

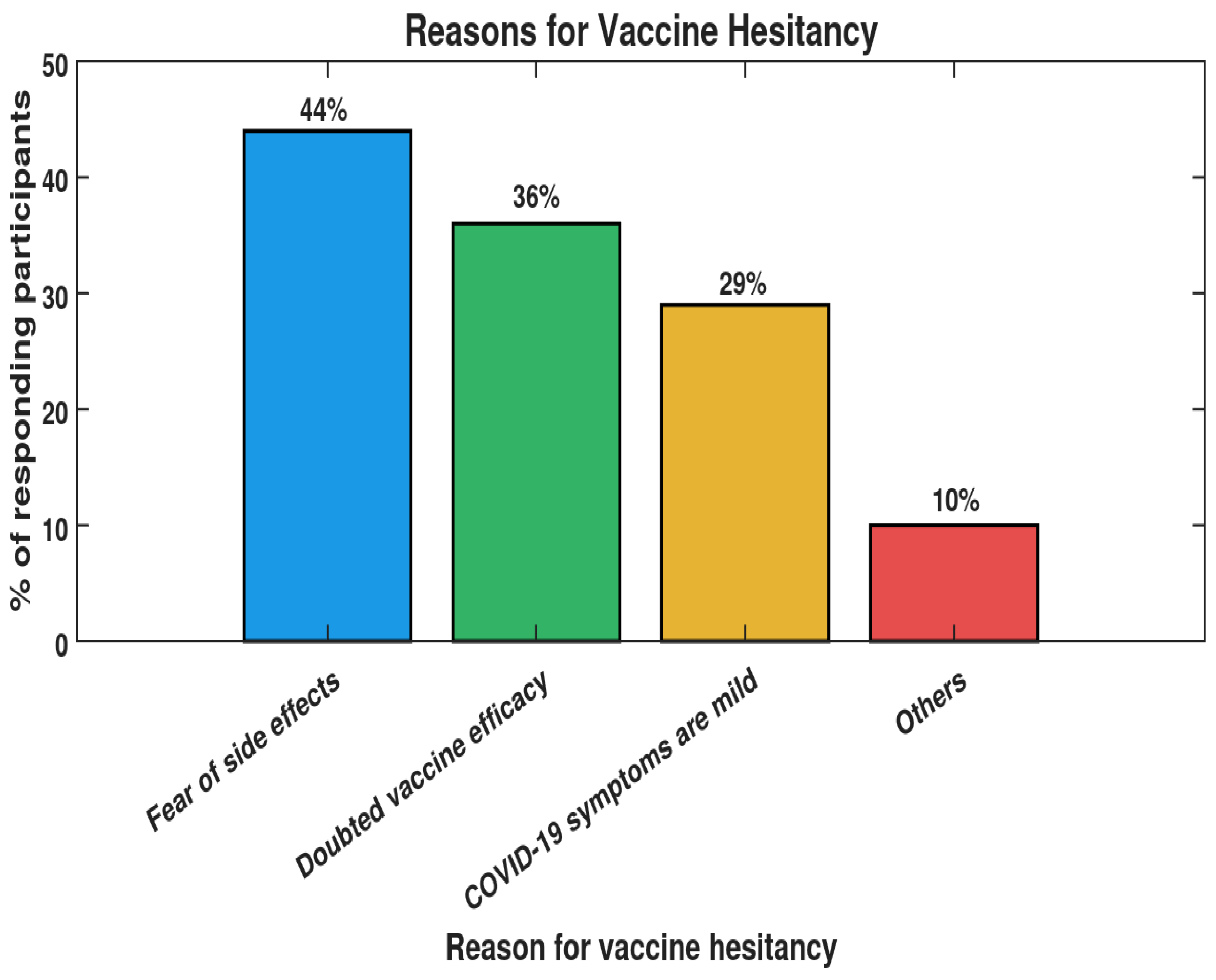

2.2. Information-Based Vaccination

3. Model Without Age Distribution

3.1. Basic Reproduction Number

- Case II: Constant rate of recovery and death. If we assume the uniform distribution of recovery and death rate

3.2. Final Size of Epidemic

4. Numerical Simulations

4.1. Simulation of the Age-Independent Model

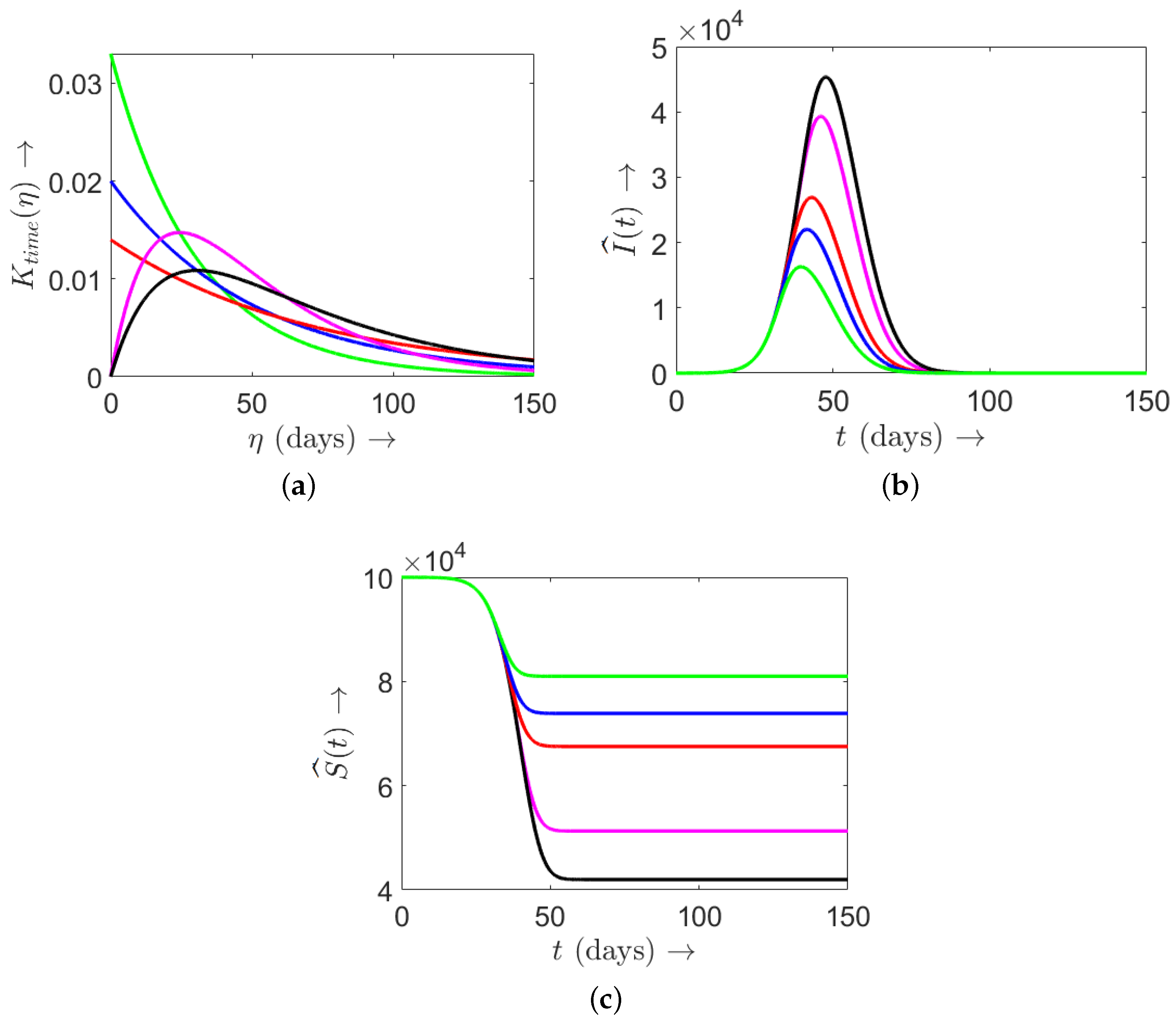

4.1.1. Effect of Memory Kernel

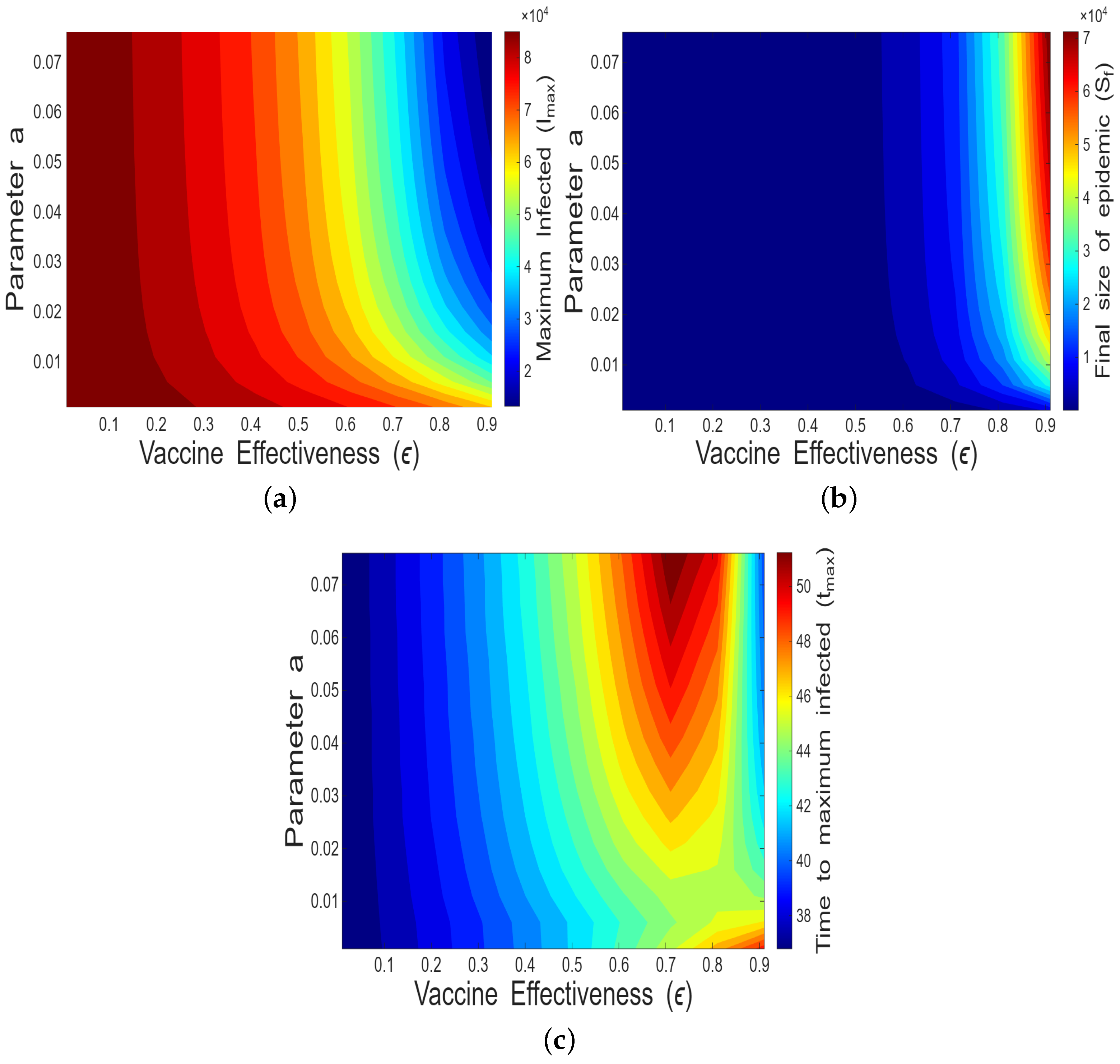

4.1.2. Impact of Vaccine Effectiveness and Decaying Memory

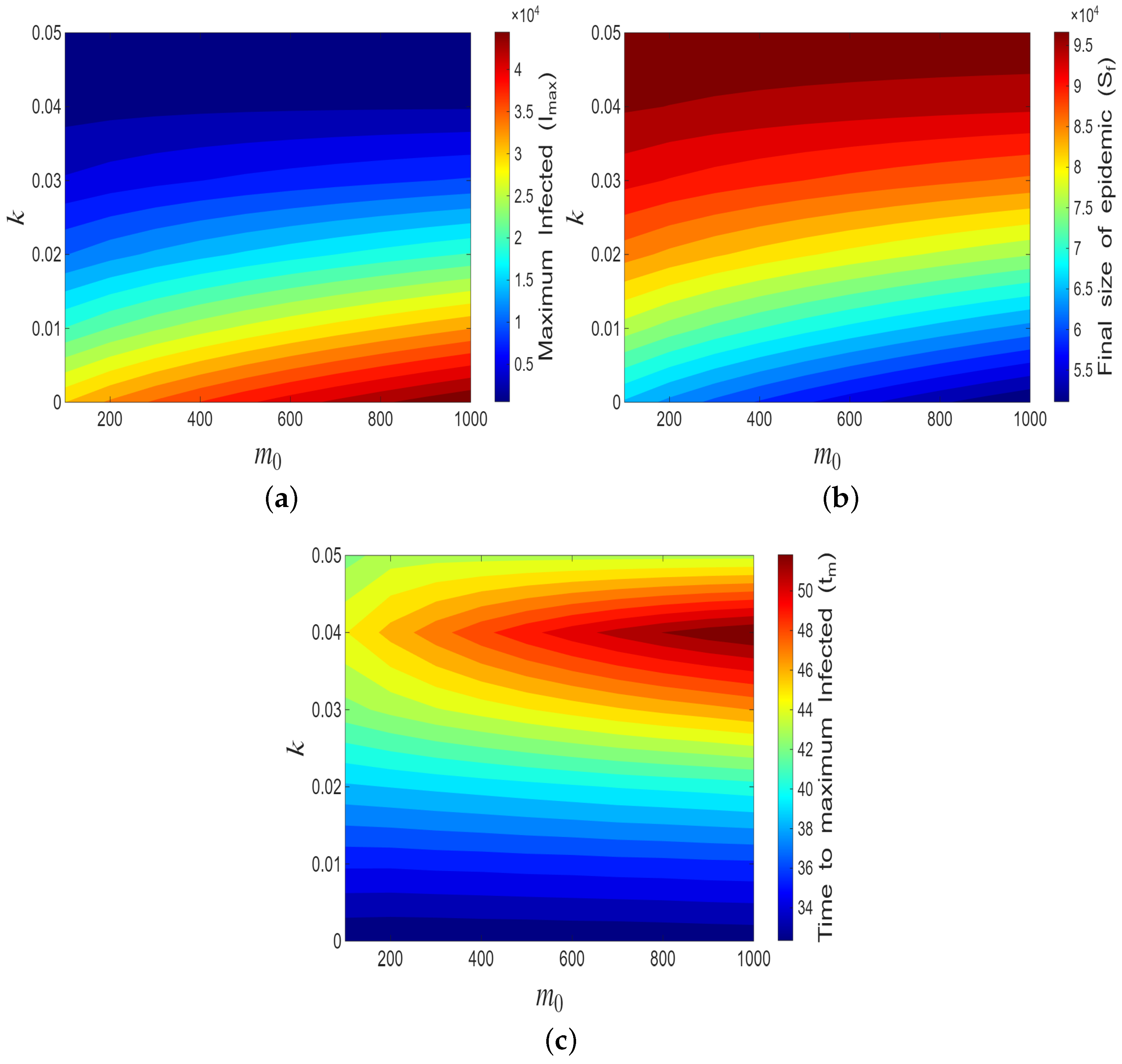

4.1.3. Impact of

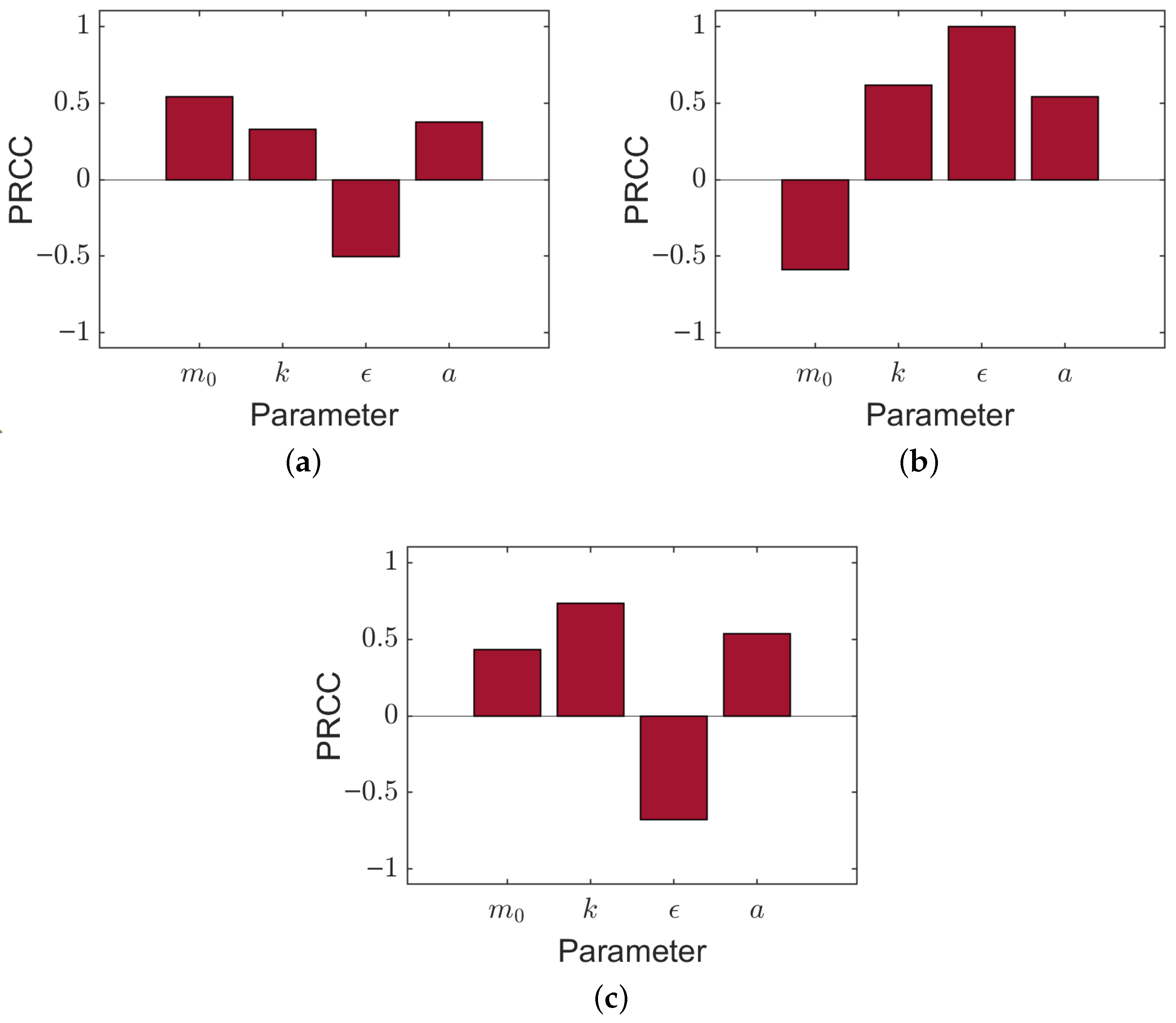

4.1.4. Sensitivity Analysis

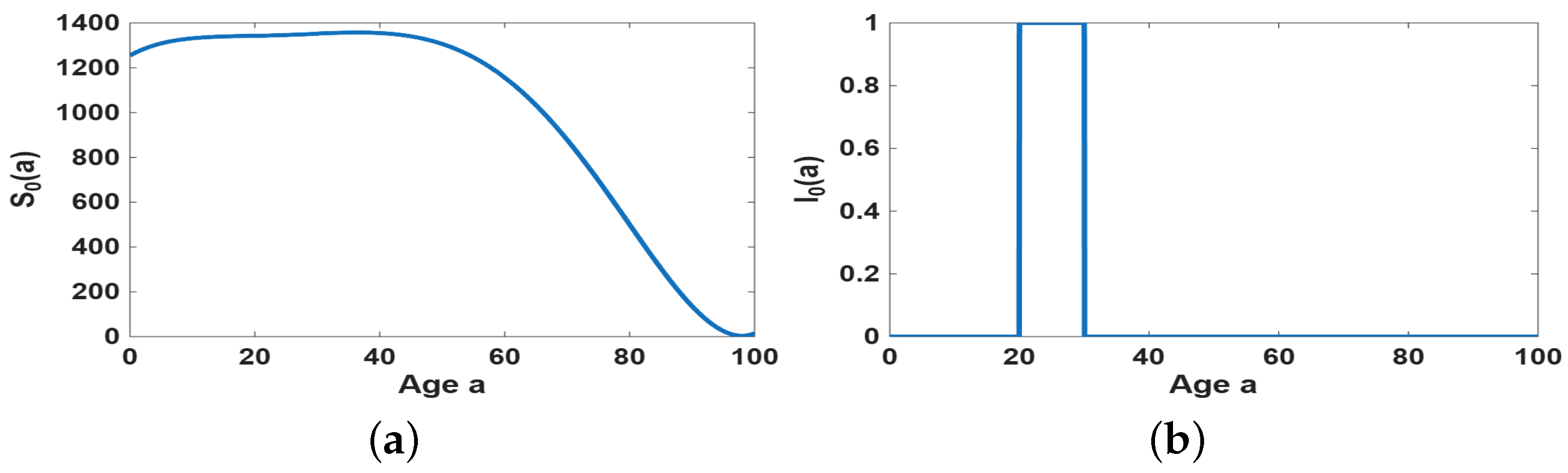

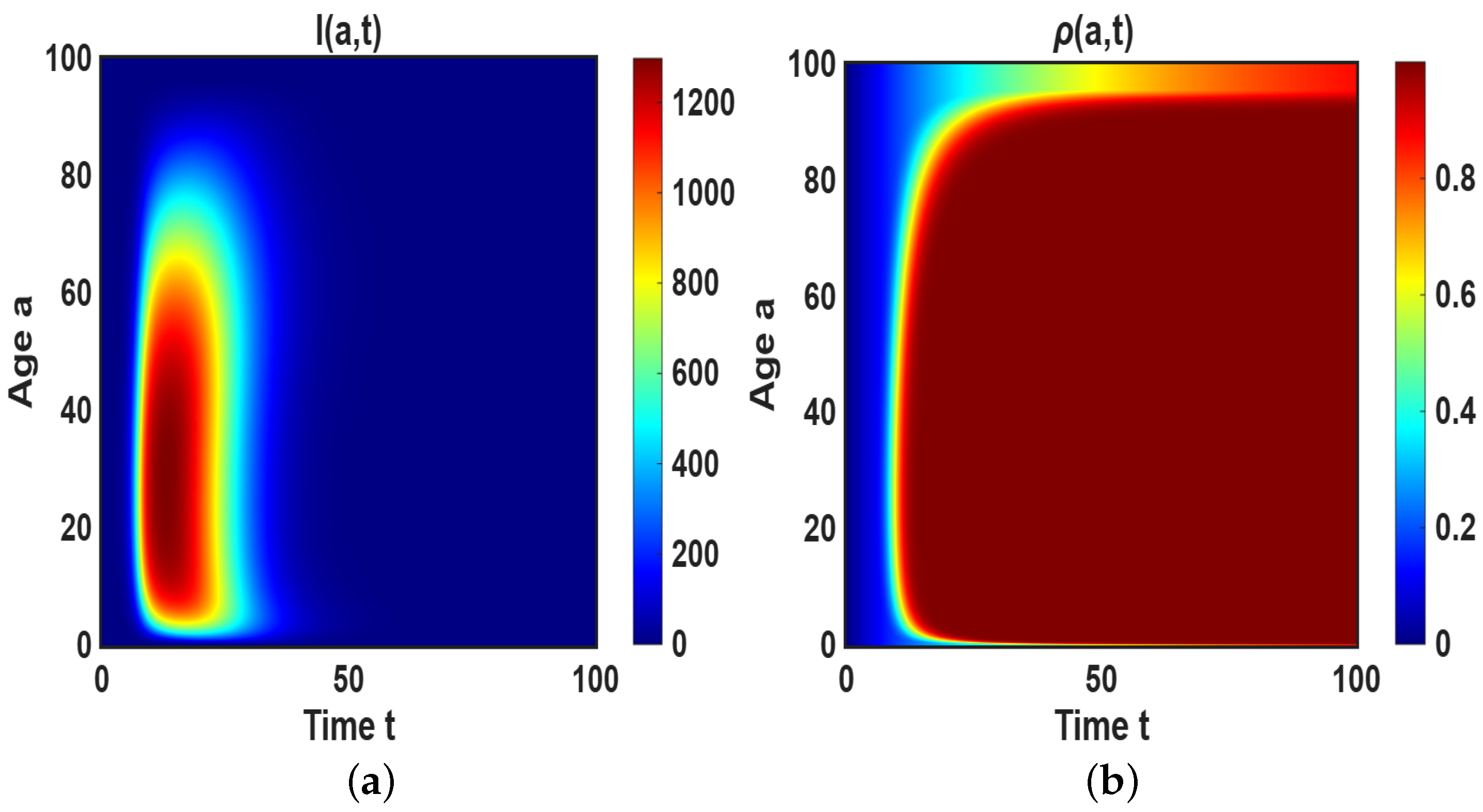

4.2. Simulation of the Age-Dependent Model

4.2.1. Impact of

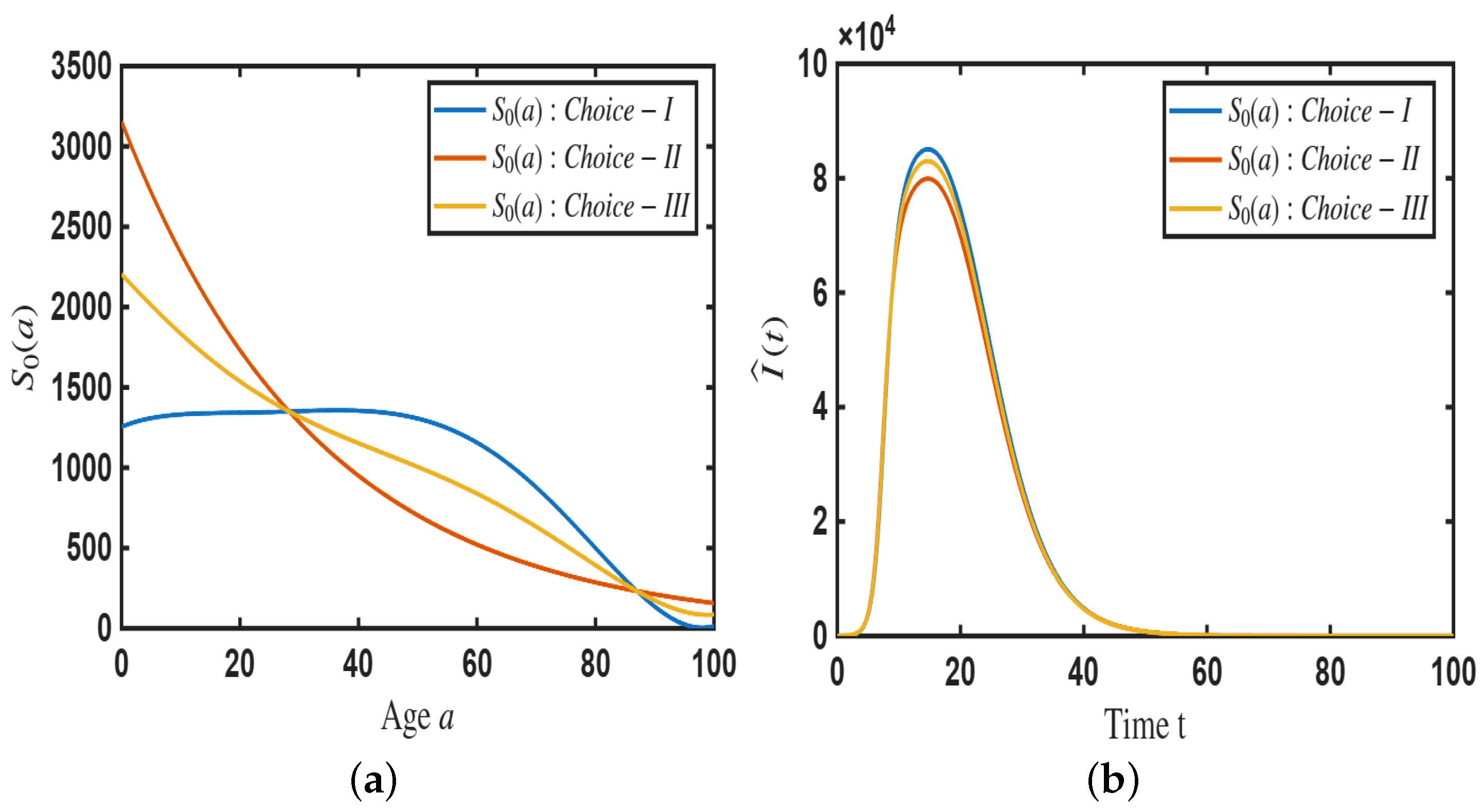

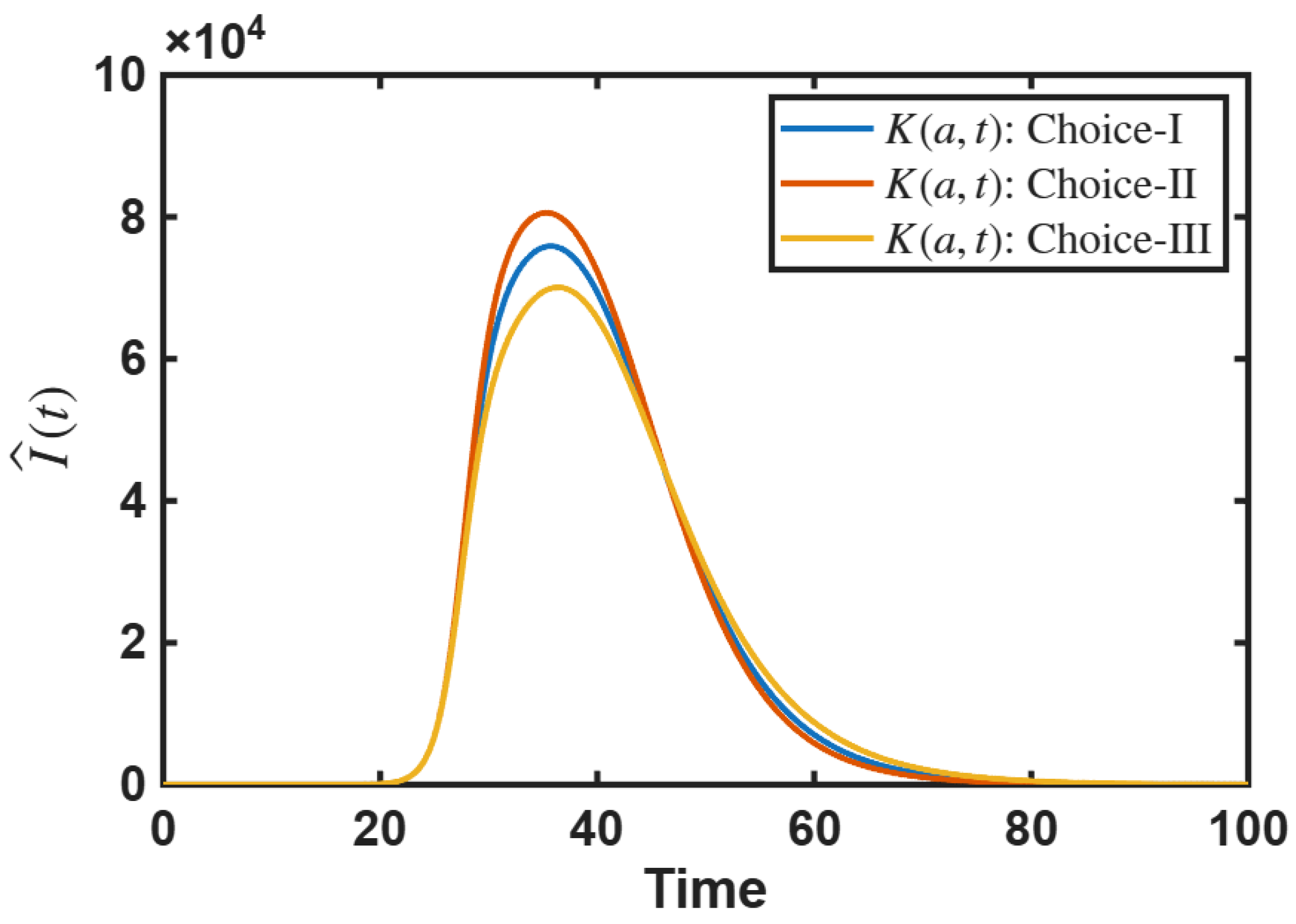

4.2.2. Impact of Age-Dependent Memory Kernel

- Choice-I:

- Choice-II:

- Choice-III:

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The age-distributed model describes disease incidence , and incorporating age-dependent vaccination decisions with the help of a memory kernel enables us to describe how past epidemic information shapes the epidemic outbreak size.

- The initial epidemic pattern is unaffected by the memory kernel, as memory effects are negligible at early stages. However, in later phases, the memory kernel significantly shapes epidemic progression, with short-term memory proving more effective in restraining outbreaks by enabling more adaptive vaccination responses to recent infection trends.

- Along with high vaccine effectiveness (), responsive vaccination (i.e., a higher value of a) is also necessary to successfully reduce the outbreak size.

- The impact of the baseline probability of vaccination (k) on outbreak control is studied.

- Age-dependent initial susceptible population and age-dependent memory kernel can influence the size of epidemic outbreak.

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Existence and Uniqueness of Positive Solution

Appendix A.1. Preliminary Results

Appendix A.2. Positiveness

Appendix A.3. Existence of Unique Positive Solution

- Now, we have

References

- Bacaër, N. Histoires de Mathématiques et de Populations; Cassini: Maidenhead, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack, W.O.; McKendrick, A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1927, 115, 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack, W.O.; McKendrick, A.G. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. ii.—The problem of endemicity. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1932, 138, 55–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack, W.O.; McKendrick, A.G. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. iii.—Further studies of the problem of endemicity. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1933, 141, 94–122. [Google Scholar]

- Martcheva, M. An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 61. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Volpert, V.l; Banerjee, M. Extended seiqr type model for covid-19 epidemic and data analysis. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 7562–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ogueda-Oliva, A.; Ghosh, A.; Banerjee, M.; Seshaiyer, P. Understanding the implications of under-reporting, vaccine efficiency, and social behavior on the post-pandemic spread using physics-informed neural networks: A case study of China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, F. Compartmental models in epidemiology. In Mathematical Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 19–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchnita, A.; Jebrane, A. A hybrid multi-scale model of covid-19 transmission dynamics to assess the potential of non-pharmaceutical interventions. Chaos Solit. Fractals 2020, 138, 109941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, R.J.; Arnott, A.; Lam, C.; Sadsad, R.; Timms, V.; Gray, K.A.; Eden, J.S.; Chang, S.; Gall, M.; Draper, J.; et al. Revealing covid-19 transmission in australia by sars-cov-2 genome sequencing and agent-based modeling. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, M.; Volpert, V. Immuno-epidemiological model-based prediction of further covid-19 epidemic outbreaks due to immunity waning. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 2022, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, M.A.; Sasaki, A. Modeling host–parasite coevolution: A nested approach based on mechanistic models. J. Theor. Biol. 2002, 218, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Bélair, J. Threshold dynamics in an seirs model with latency and temporary immunity. J. Math. Biol. 2014, 69, 875–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, M.; Chattopadhyay, A.K. Effect of vaccine dose intervals: Considering immunity levels, vaccine efficacy, and strain variants for disease control strategy. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, M.J.; Eames, K.D. Networks and epidemic models. J. R. Soc. Interface 2005, 2, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, B.Y.; Kohane, I.S.; Mandl, K.D. An epidemiological network model for disease outbreak detection. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, N.; Burini, D.; Outada, N. Pandemics of mutating virus and society: A multi-scale active particles approach. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20210161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soubeyrand, S.; Thébaud, G.; Chadoeuf, J. Accounting for biological variability and sampling scale: A multi-scale approach to building epidemic models. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magal, P.; Ruan, S. Age-structured models. In Theory and Applications of Abstract Semilinear Cauchy Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 357–449. [Google Scholar]

- Ducrot, A.; Magal, P.; Ruan, S. Travelling wave solutions in multigroup age-structured epidemic models. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 2010, 195, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, B.; Perasso, A. Threshold behaviour of a SI epidemiological model with two structuring variables. J. Evol. Equ. 2016, 16, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H. Threshold and stability results for an age-structured epidemic model. J. Math. Biol. 1990, 28, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H. Age-Structured Population Dynamics in Demography and Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 287–331. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.-Z.; Yang, J.; Martcheva, M. Age Structured Epidemic Modeling; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 52. [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot, J.; Griette, Q.; Maday, Y.; Magal, P. A Kermack–McKendrick model with age of infection starting from a single or multiple cohorts of infected patients. Proc. R. Soc. A 2023, 479, 20220381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Volpert, V.; Banerjee, M. An epidemic model with time-distributed recovery and death rates. Bull. Math. Biol. 2022, 84, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Magal, P. Data-driven mathematical modeling approaches for COVID-19: A survey. Phys. Life Rev. 2024, 50, 166–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Griette, Q.; Magal, P.; Webb, G. Modeling vaccine efficacy for COVID-19 outbreak in New York City. Biology 2022, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Magal, P.; Seydi, O.; Webb, G. Predicting the cumulative number of cases for the COVID-19 epidemic in China from early data. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 3040–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omame, A.; Abbas, M.; Onyenegecha, C.P. Backward bifurcation and optimal control in a co-infection model for SARS-CoV-2 and ZIKV. Results Phys. 2022, 37, 105481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omame, A.; Okuonghae, D. A co-infection model for oncogenic human papillomavirus and tuberculosis with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2021, 42, 1081–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, B. A note on the direction of the transcritical bifurcation in epidemic models. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 2015, 20, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniya, T. Hopf bifurcation in an age-structured SIR epidemic model. Appl. Math. Lett. 2019, 92, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, D. Hopf bifurcation in epidemic models with a latent period and nonpermanent immunity. Math. Comput. Model. 1997, 25, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderrama, R.; Peressutti, J.; Pinasco, J.P.; Vazquez, F.; de la Vega, C.S. Optimal control for a SIR epidemic model with limited quarantine. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, T.T.; Benyah, F. Optimal control of vaccination and treatment for an SIR epidemiological model. World J. Model. Simul. 2012, 8, 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Nisar, K.S.; Farman, M.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Ravichandran, C. A review of fractional order epidemic models for life sciences problems: Past, present and future. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 95, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Zarin, R.; Khan, S.; Saeed, A.; Gul, T.; Humphries, U.W. Fractional dynamics and stability analysis of COVID-19 pandemic model under the harmonic mean type incidence rate. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 25, 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Zarin, R.; Hussain, G.; Usman, A.H.; Humphries, U.W.; Gomez-Aguilar, J.F. Modeling and sensitivity analysis of HBV epidemic model with convex incidence rate. Results Phys. 2021, 22, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.J.S. A primer on stochastic epidemic models: Formulation, numerical simulation, and analysis. Infect. Dis. Model. 2017, 2, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Satorras, R.; Vespignani, A. Epidemic spreading in scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Satorras, R.; Castellano, C.; Van Mieghem, P.; Vespignani, A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 925–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Al-Ghamdi, A.S.A.-M.; Alassafi, M.O.; AlGhamdi, S.A. Machine learning, deep learning, and mathematical models to analyze forecasting and epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millevoi, C.; Pasetto, D.; Ferronato, M. A Physics-Informed Neural Network approach for compartmental epidemiological models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Kennedy, C.M.; Kevrekidis, P.G.; Zhang, H.-K. A modified PINN approach for identifiable compartmental models in epidemiology with application to COVID-19. Viruses 2022, 14, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, P.; D’Onofrio, A. Modeling the Interplay Between Human Behavior and the Spread of Infectious Diseases; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bauch, C.T.; Bhattacharyya, S.; d’Onofrio, A.; Manfredi, P.; Perc, M.; Perra, N.; Salathé, M.; Zhao, D. Statistical physics of vaccination. Phys. Rep. 2016, 664, 1–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perra, N. Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Phys. Rep. 2021, 913, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galagali, P.M.; Kinikar, A.A.; Kumar, V.S. Vaccine hesitancy: Obstacles and challenges. Curr. Pediatr. Rep. 2022, 10, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support covid-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, L. The sociological study of stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1989, 30, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

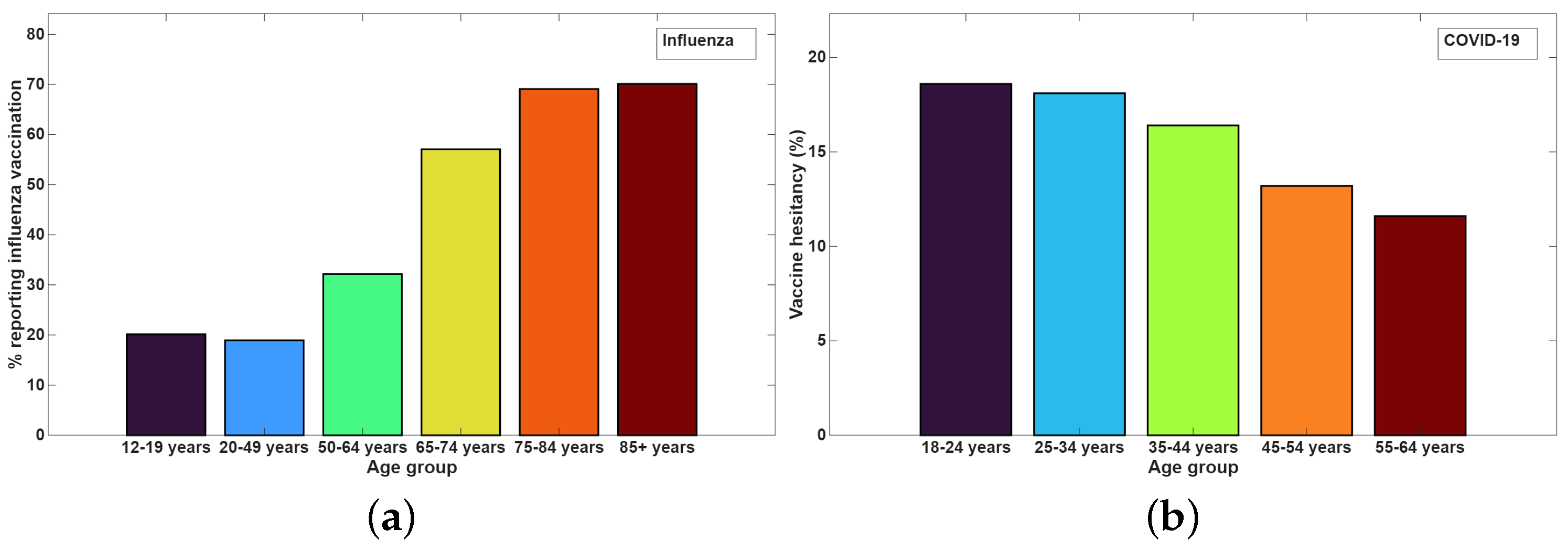

- Buchan, S.A.; Kwong, J.C. Trends in influenza vaccine coverage and vaccine hesitancy in Canada, 2006/07 to 2013/14: Results from cross-sectional survey data. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 4, E455–E462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzinger, M.; Watson, V.; Arwidson, P.; Alla, F.; Luchini, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: A survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e210–e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, F.; Ganesan, S.; James, A.; Zaher, W.A. Understanding perception and acceptance of sinopharm vaccine and vaccination against COVID-19 in the UAE. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordina, M.; Lauri, M.A. Attitudes towards covid-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; Exel, J.V.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? a european survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Volpert, V.; Banerjee, M. An age-dependent immuno-epidemiological model with distributed recovery and death rates. J. Math. Biol. 2023, 86, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G.F.; D’Agata, E.M.C.; Magal, P.; Ruan, S. A model of antibiotic-resistant bacterial epidemics in hospitals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13343–13348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Onofrio, A.; Manfredi, P.; Salinelli, E. Vaccinating behaviour, information, and the dynamics of sir vaccine preventable diseases. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2007, 71, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Volpert, V.; Banerjee, M. An epidemic model with time delay determined by the disease duration. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.; Ghosh, S.; Manfredi, P.; d’Onofrio, A. Spatio-temporal chaos and clustering induced by nonlocal information and vaccine hesitancy in the SIR epidemic model. Chaos Solit. Fractals 2023, 170, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, S.S.; Hogue, I.B.; Ray, C.J.; Kirschner, D.E. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. J. Theor. Biol. 2008, 254, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Dugas, M.; Ramaprasad, J.; Luo, J.; Li, G.; Gao, G. Socioeconomic privilege and political ideology are associated with racial disparity in COVID-19 vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2107873118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watel, P.P.; Seror, V.; Cortaredona, S.; Launay, O.; Raude, J.; Verger, P.; Fressard, L.; Beck, F.; Legleye, S.; l’Haridon, O.; et al. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marca, R.D.; d’Onofrio, A. Volatile opinions and optimal control of vaccine awareness campaigns: Chaotic behaviour of the forward-backward sweep algorithm vs. heuristic direct optimization. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2021, 98, 105768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupica, A.; Manfredi, P.; Volpert, V.; Palumbo, A.; d’Onofrio, A. Spatio-temporal games of voluntary vaccination in the absence of the infection: The interplay of local versus non-local information about vaccine adverse events. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1090–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgaertner, B.; Ridenhour, B.J.; Justwan, F.; Carlisle, J.E.; Miller, C.R. Risk of disease and willingness to vaccinate in the united states: A population-based survey. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y. Willingness to pay for a covid-19 vaccine. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2021, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopi, A.P.; Kumar, S.G.; Subitha, L.; Patel, N. Vaccine hesitancy among the nursing officers working in a tertiary care hospital, Puducherry—A mixed-method study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 22, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjorang, C.; Pangandaheng, N.; Tinungki, Y.; Medea, P.G. The determinants of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in a rural area of an Indonesia–Philippines border island: A mixed-method study. Enferm. Clin. 2022, 32, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, A.; Haile, K.; Timerga, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical and health science students attending Wolkite University in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waezizadeh, T.; Mehrpooya, A.; Rezaeizadeh, M.; Yarahmadian, S. Mathematical models for the effects of hypertension and stress on kidney and their uncertainty. Math. Biosci. 2018, 305, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, M.W.; Sattenspiel, L.; Ntaimo, L. Finding optimal vaccination strategies under parameter uncertainty using stochastic programming. Math. Biosci. 2008, 215, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner, M.; Zehnder, S.; Dietz, K. An age-structured model for measles vaccination. In Models for Infectious Human Diseases: Their Structure and Relation to Data; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Auzenbergs, M.; Fu, H.; Abbas, K.; Procter, S.R.; Cutts, F.T.; Jit, M. Health effects of routine measles vaccination and supplementary immunisation activities in 14 high-burden countries: A Dynamic Measles Immunization Calculation Engine (DynaMICE) modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1194–e1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, S. Sur les opérations dans les ensembles abstraits et leur application aux équations intégrales. Fund. Math. 1922, 3, 133–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable and | Description | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | ||

| Susceptible individuals of age a at time t | ||

| Infected individuals of age a at time t | ||

| Recovered individuals of age a at time t | ||

| Dead individuals of age a at time t | ||

| Newly infected individuals of age a at time t | ||

| Proportion of vaccinated individuals of age a at time t | ||

| Recovery rate distribution of age a at time since infection | ||

| Death rate distribution of age a at time since infection | ||

| Susceptibility rate at the age a | ||

| Viral load at any time during the infectiousness period of an infected individual of age a | ||

| Vaccine effectiveness | ||

| Maximum possible age of an individual | ||

| Probability of vaccine uptake | ||

| Information index in the age group a at time t |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, M.; Volpert, V. An Age-Distributed Immuno-Epidemiological Model with Information-Based Vaccination Decision. Mathematics 2026, 14, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010162

Ghosh S, Banerjee M, Volpert V. An Age-Distributed Immuno-Epidemiological Model with Information-Based Vaccination Decision. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhosh, Samiran, Malay Banerjee, and Vitaly Volpert. 2026. "An Age-Distributed Immuno-Epidemiological Model with Information-Based Vaccination Decision" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010162

APA StyleGhosh, S., Banerjee, M., & Volpert, V. (2026). An Age-Distributed Immuno-Epidemiological Model with Information-Based Vaccination Decision. Mathematics, 14(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010162