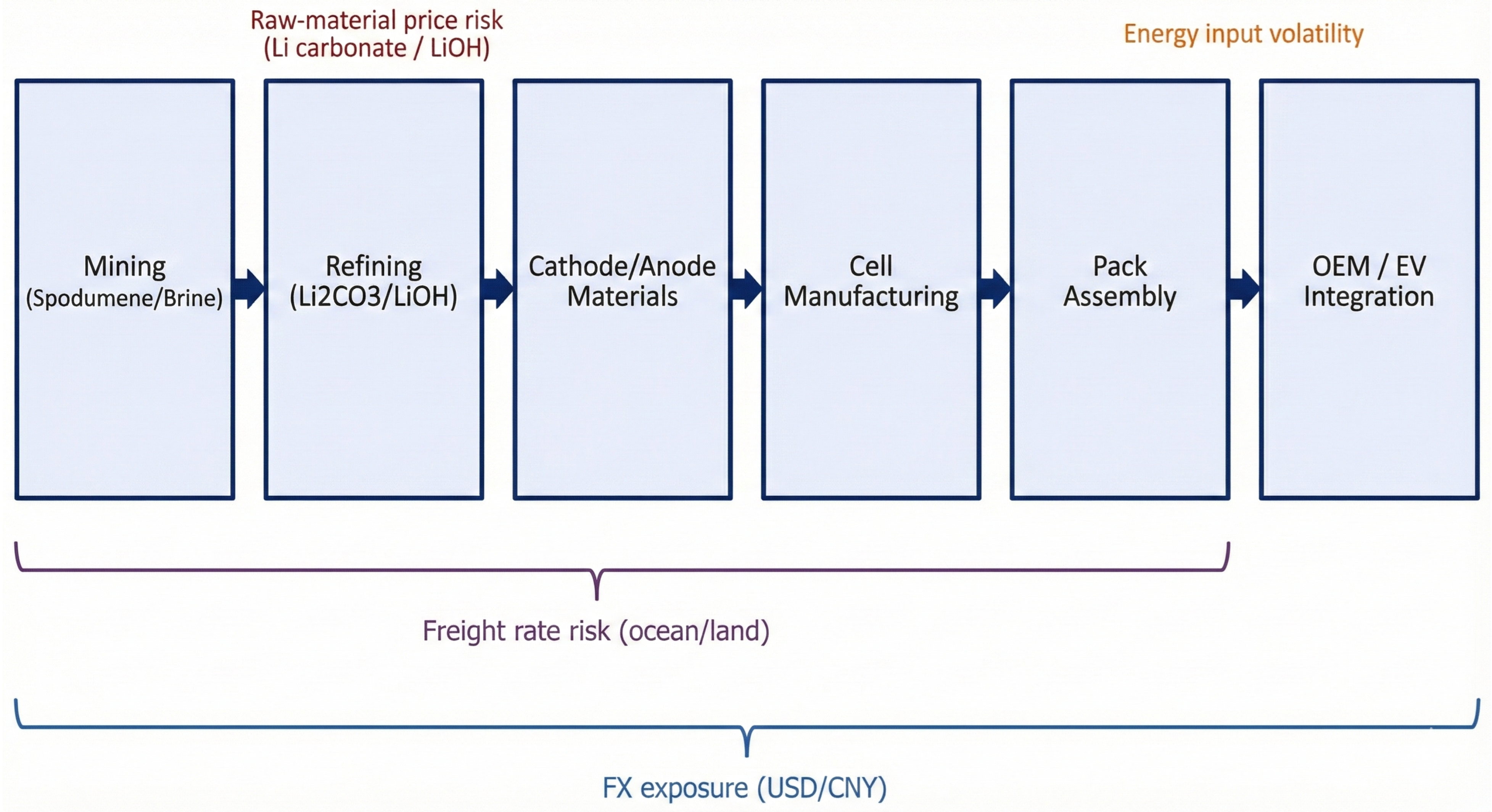

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of the lithium battery supply chain and major risk exposure channels.

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of the lithium battery supply chain and major risk exposure channels.

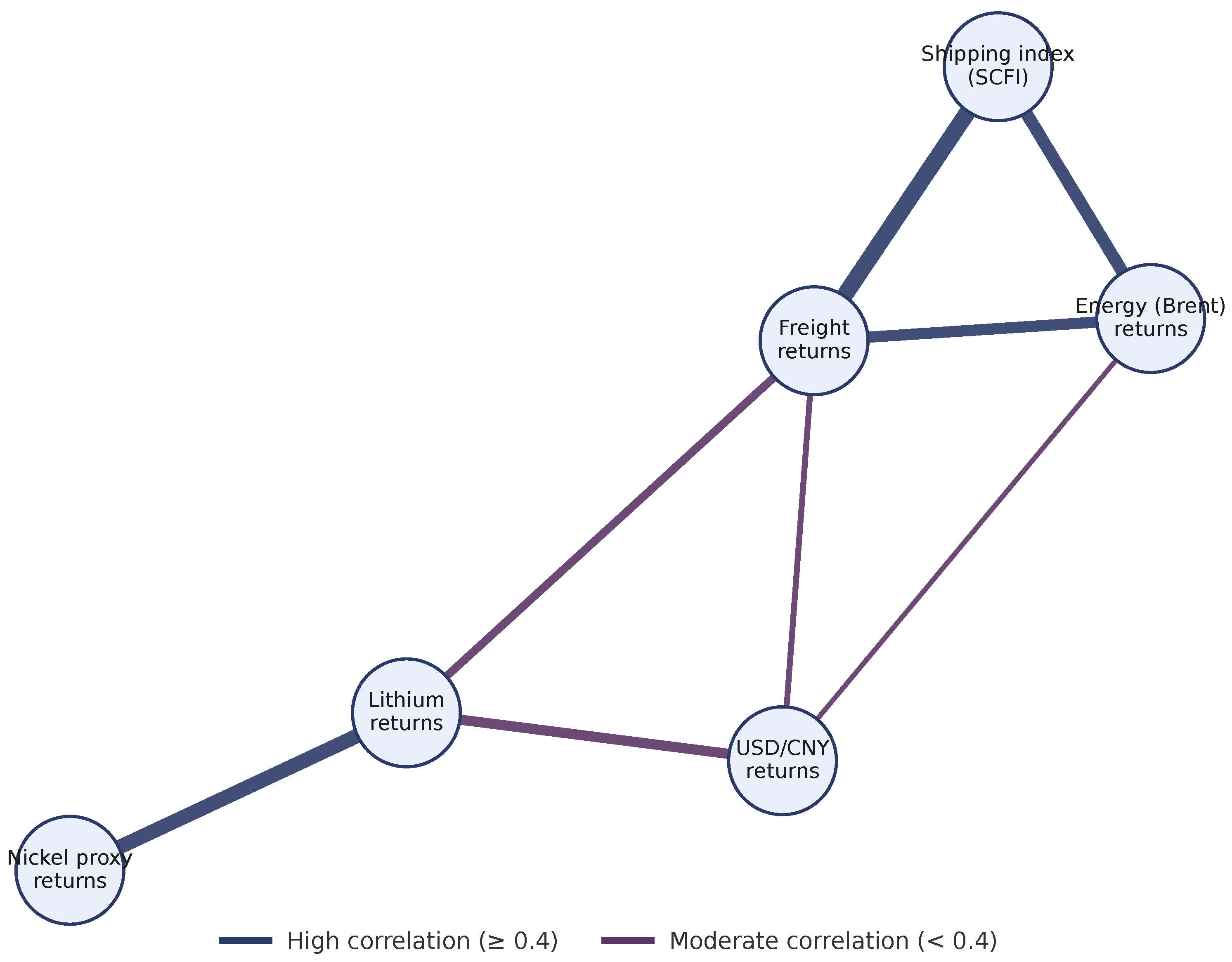

Figure 2.

Illustrative correlation network of lithium, exchange rate, and freight returns.

Figure 2.

Illustrative correlation network of lithium, exchange rate, and freight returns.

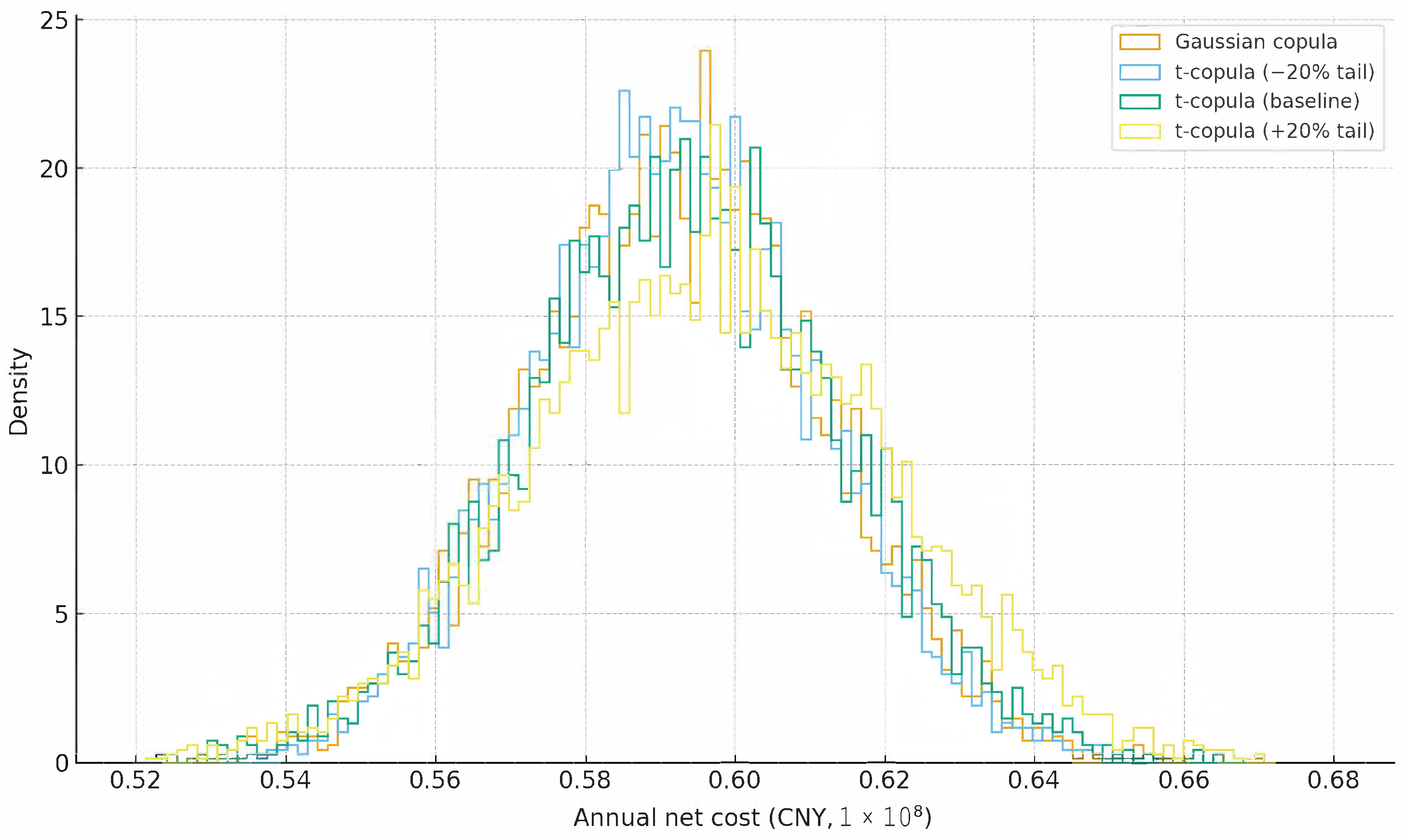

Figure 3.

Sensitivity of the annual net cost distribution to copula specifications in Case Study I. The density plots illustrate the performance of the proposed discrete CVaR hedge under four different dependence structures: a Gaussian copula (orange), the baseline Student-t copula (green), and Student-t copulas with tail dependence parameters decreased by 20% (light blue) and increased by 20% (yellow). The x-axis represents the annual net cost in CNY (), and the y-axis represents the probability density. Observe that the distributions overlap significantly, indicating that the hedging performance is stable across different dependence assumptions. This confirms that the model’s robustness is not driven by a specific choice of copula or tail parameter.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity of the annual net cost distribution to copula specifications in Case Study I. The density plots illustrate the performance of the proposed discrete CVaR hedge under four different dependence structures: a Gaussian copula (orange), the baseline Student-t copula (green), and Student-t copulas with tail dependence parameters decreased by 20% (light blue) and increased by 20% (yellow). The x-axis represents the annual net cost in CNY (), and the y-axis represents the probability density. Observe that the distributions overlap significantly, indicating that the hedging performance is stable across different dependence assumptions. This confirms that the model’s robustness is not driven by a specific choice of copula or tail parameter.

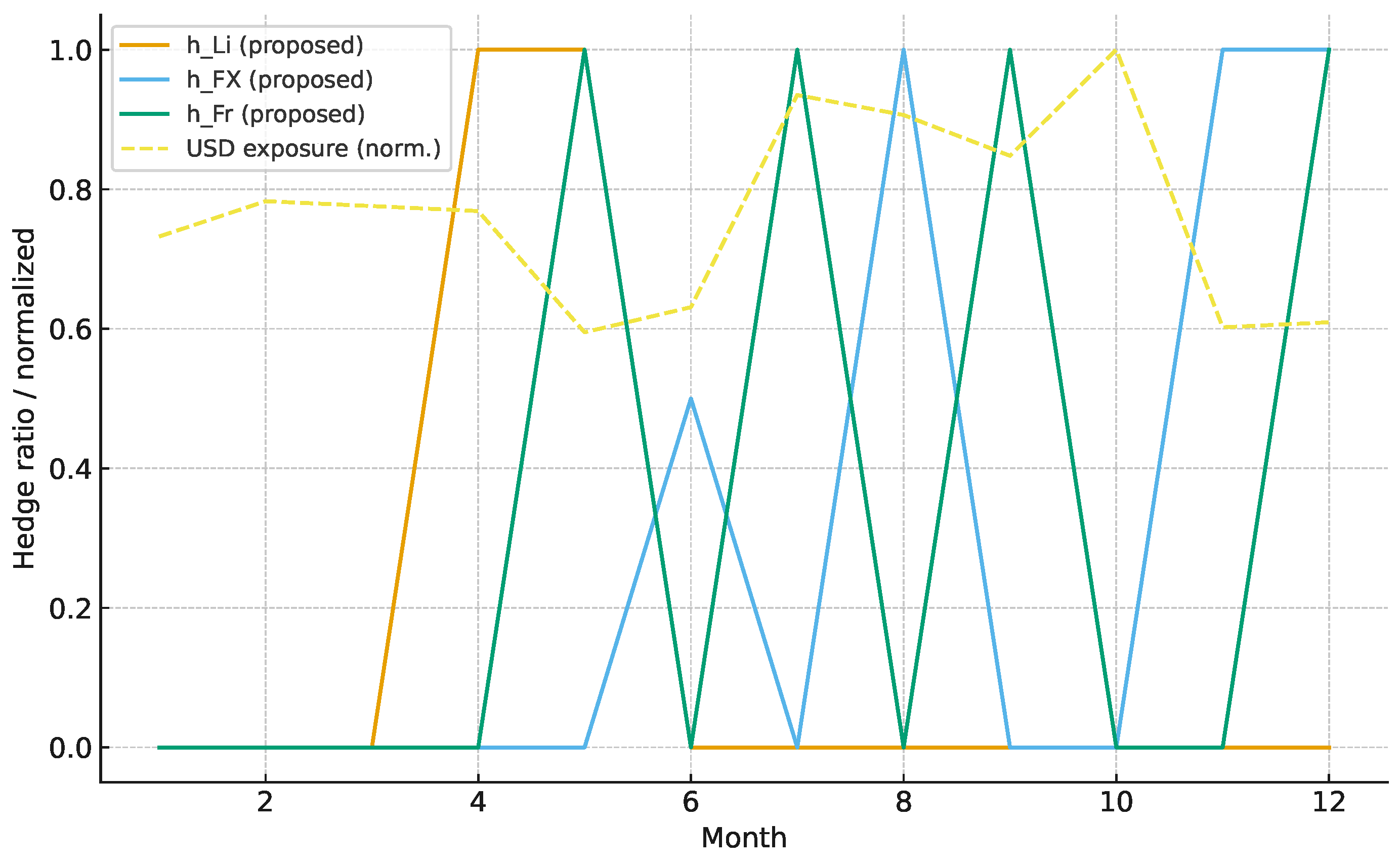

Figure 4.

Discrete hedge ratio dynamics and exposure response over a 12-month horizon. The trajectories display the optimal hedge ratios for lithium (orange solid), foreign exchange (blue solid), and freight (green solid) alongside the normalised USD exposure (yellow dashed). The decision space is restricted to an implementable grid . Observe the “step-like” activation pattern: the model maintains a low or partial hedge (0 or 0.5) during periods of moderate volatility but switches sharply to a full hedge (1.0) when risk metrics cross a critical threshold (e.g., Months 5–8). This demonstrates the model’s sparsity property, acting as a noise filter that ignores minor fluctuations while providing full insulation against significant tail risks.

Figure 4.

Discrete hedge ratio dynamics and exposure response over a 12-month horizon. The trajectories display the optimal hedge ratios for lithium (orange solid), foreign exchange (blue solid), and freight (green solid) alongside the normalised USD exposure (yellow dashed). The decision space is restricted to an implementable grid . Observe the “step-like” activation pattern: the model maintains a low or partial hedge (0 or 0.5) during periods of moderate volatility but switches sharply to a full hedge (1.0) when risk metrics cross a critical threshold (e.g., Months 5–8). This demonstrates the model’s sparsity property, acting as a noise filter that ignores minor fluctuations while providing full insulation against significant tail risks.

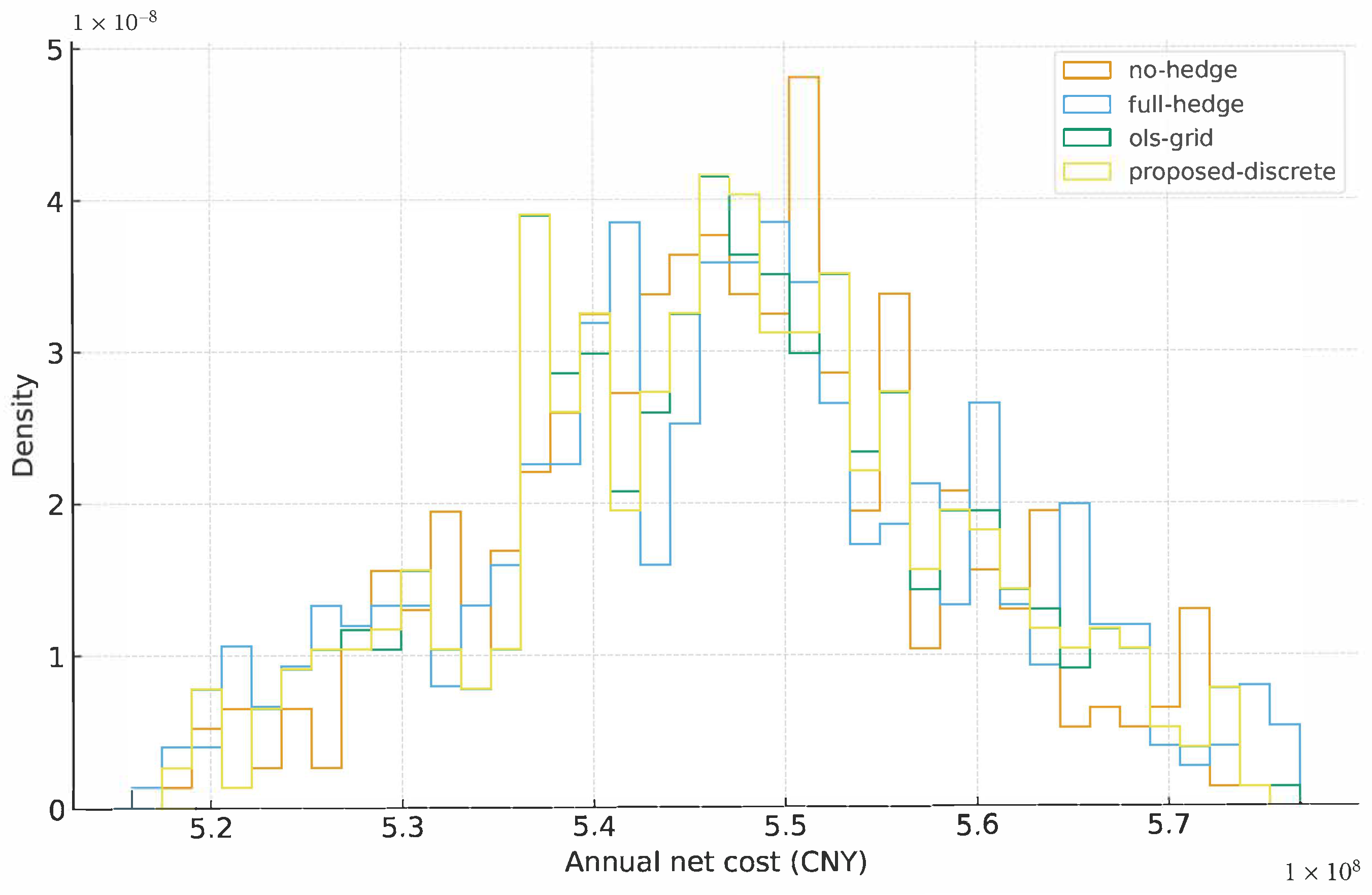

Figure 5.

Probability density estimation of annual net procurement costs under competing strategies. The histograms illustrate the cost distribution profiles for the unhedged baseline (orange), full-hedge (blue), OLS-grid (green), and the proposed discrete CVaR model (yellow). The x-axis represents the annual net cost in CNY, and the y-axis represents the probability density. Note the distinct shape of the proposed discrete strategy (yellow): it achieves a structural advantage by eliminating the long right tail of the unhedged strategy (avoiding extreme losses) while maintaining a lower mean cost than the full-hedge strategy (avoiding expensive over-hedging). This visibly narrower and more symmetric distribution demonstrates the model’s ability to reduce kurtosis and stabilise cash flows without paying the excessive risk premium required by a full-coverage policy.

Figure 5.

Probability density estimation of annual net procurement costs under competing strategies. The histograms illustrate the cost distribution profiles for the unhedged baseline (orange), full-hedge (blue), OLS-grid (green), and the proposed discrete CVaR model (yellow). The x-axis represents the annual net cost in CNY, and the y-axis represents the probability density. Note the distinct shape of the proposed discrete strategy (yellow): it achieves a structural advantage by eliminating the long right tail of the unhedged strategy (avoiding extreme losses) while maintaining a lower mean cost than the full-hedge strategy (avoiding expensive over-hedging). This visibly narrower and more symmetric distribution demonstrates the model’s ability to reduce kurtosis and stabilise cash flows without paying the excessive risk premium required by a full-coverage policy.

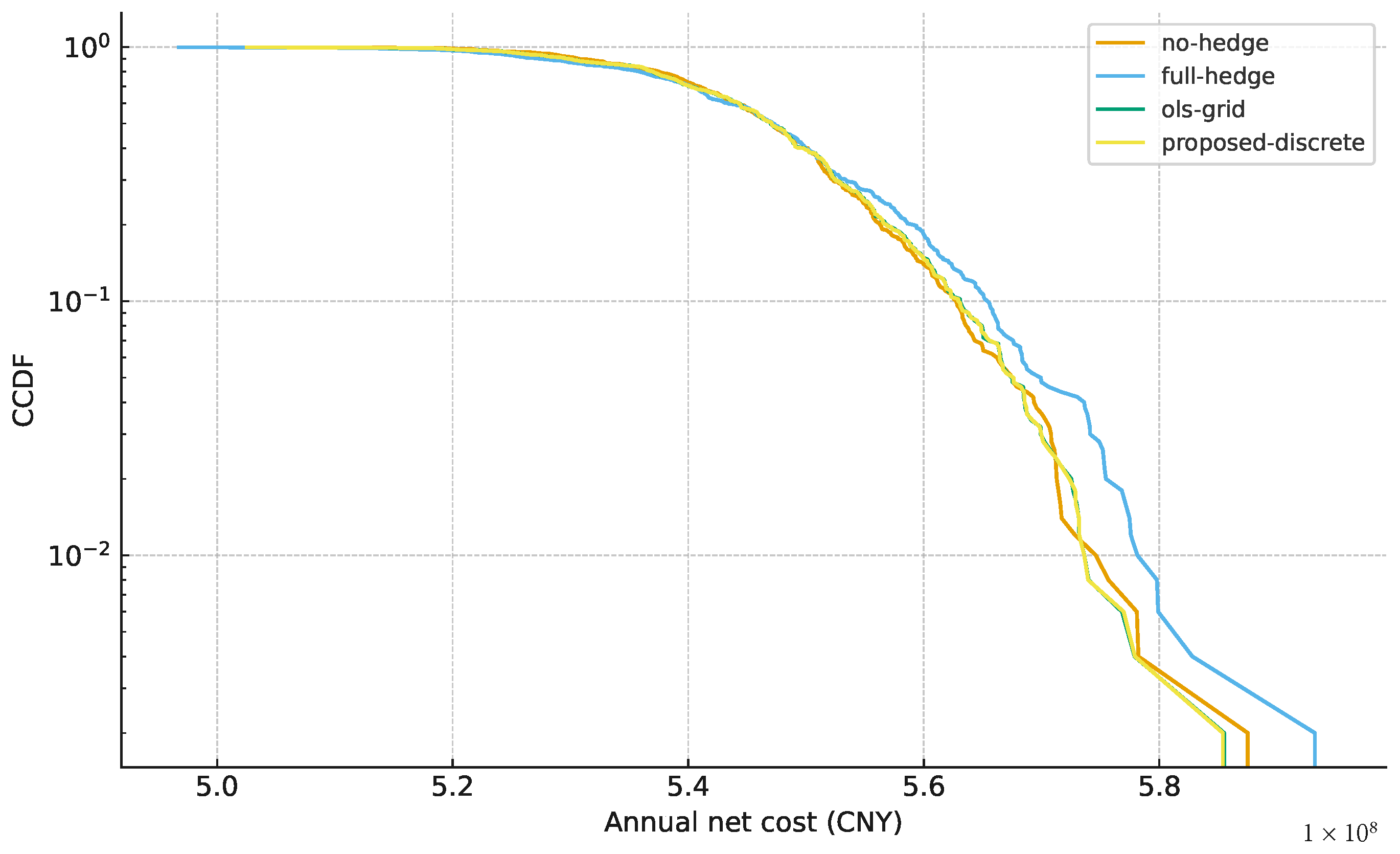

Figure 6.

Tail-risk comparison via Complementary CDF (CCDF) of annual net costs. The curves plot the probability on a logarithmic scale against annual cost in CNY. The strategies compared are the unhedged baseline (orange), full-hedge (blue), OLS-grid (green), and the proposed discrete CVaR framework (yellow). Observe that the proposed discrete strategy (yellow) exhibits the fastest tail decay in the extreme high-cost region (> CNY). Unlike the continuous OLS hedge, which diverges in the deep tail due to parameter sensitivity, the discrete model effectively suppresses extreme outliers. This validates the “regularization” effect of the discrete grid, which filters out estimation noise and minimises the probability of catastrophic loss.

Figure 6.

Tail-risk comparison via Complementary CDF (CCDF) of annual net costs. The curves plot the probability on a logarithmic scale against annual cost in CNY. The strategies compared are the unhedged baseline (orange), full-hedge (blue), OLS-grid (green), and the proposed discrete CVaR framework (yellow). Observe that the proposed discrete strategy (yellow) exhibits the fastest tail decay in the extreme high-cost region (> CNY). Unlike the continuous OLS hedge, which diverges in the deep tail due to parameter sensitivity, the discrete model effectively suppresses extreme outliers. This validates the “regularization” effect of the discrete grid, which filters out estimation noise and minimises the probability of catastrophic loss.

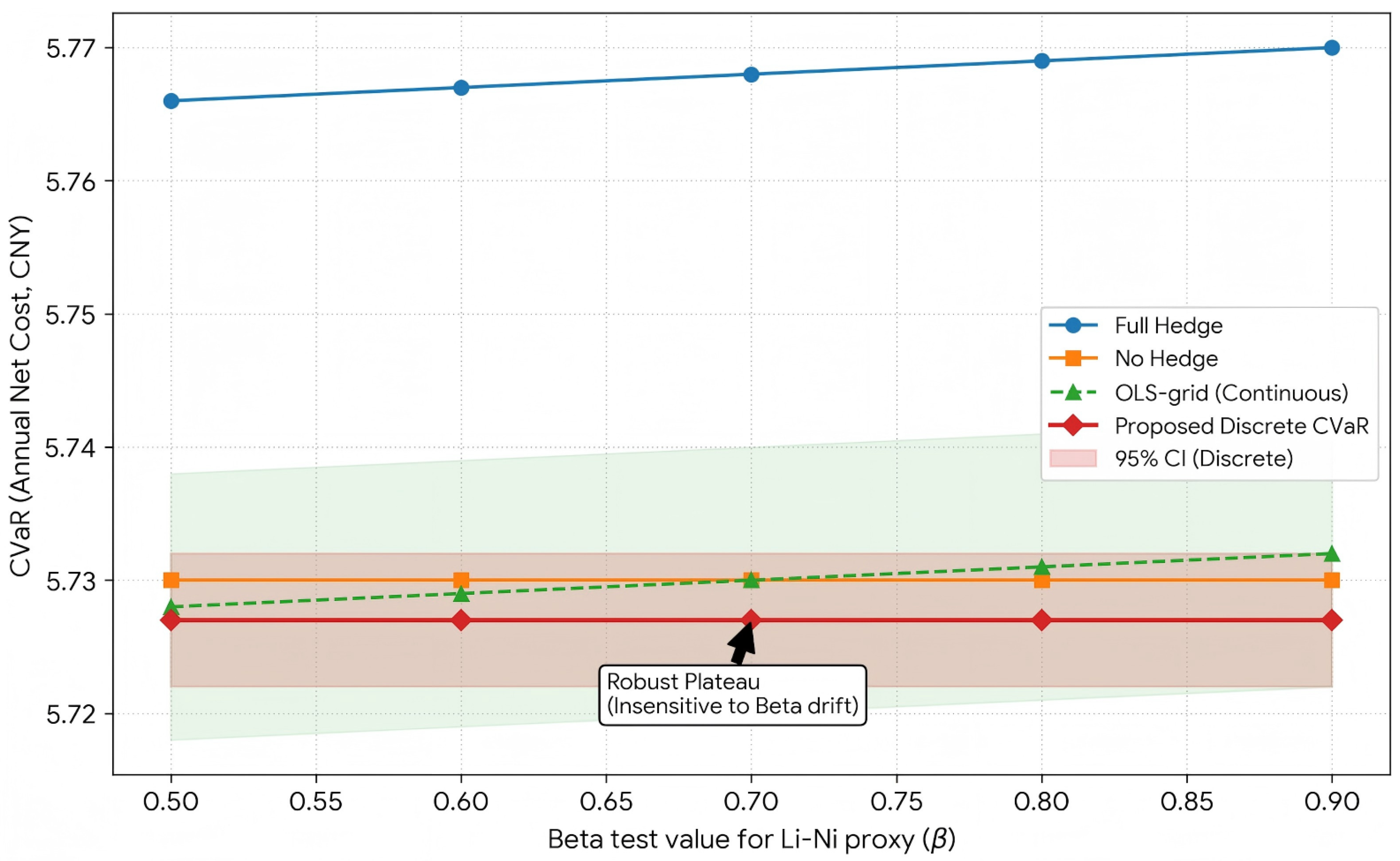

Figure 7.

Parameter-drift robustness of discrete vs. continuous hedges with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. The plot illustrates the sensitivity of the portfolio’s tail risk () to deviations in the estimated regression coefficient () for the Lithium-Nickel proxy. The proposed discrete CVaR strategy (red solid line) is compared against the continuous OLS benchmark (green dashed line), full hedge (blue), and no hedge (orange).The red and green shaded regions indicate the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the discrete and continuous strategies, respectively. Note the “Robust Plateau” exhibited by the discrete strategy: the risk profile remains flat and stable even as the parameter drifts significantly from the baseline. This confirms that the discretization of decision space acts as a filter against estimation error, whereas the continuous OLS hedge deteriorates (slope increases) when the parameter is mis-specified.

Figure 7.

Parameter-drift robustness of discrete vs. continuous hedges with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. The plot illustrates the sensitivity of the portfolio’s tail risk () to deviations in the estimated regression coefficient () for the Lithium-Nickel proxy. The proposed discrete CVaR strategy (red solid line) is compared against the continuous OLS benchmark (green dashed line), full hedge (blue), and no hedge (orange).The red and green shaded regions indicate the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the discrete and continuous strategies, respectively. Note the “Robust Plateau” exhibited by the discrete strategy: the risk profile remains flat and stable even as the parameter drifts significantly from the baseline. This confirms that the discretization of decision space acts as a filter against estimation error, whereas the continuous OLS hedge deteriorates (slope increases) when the parameter is mis-specified.

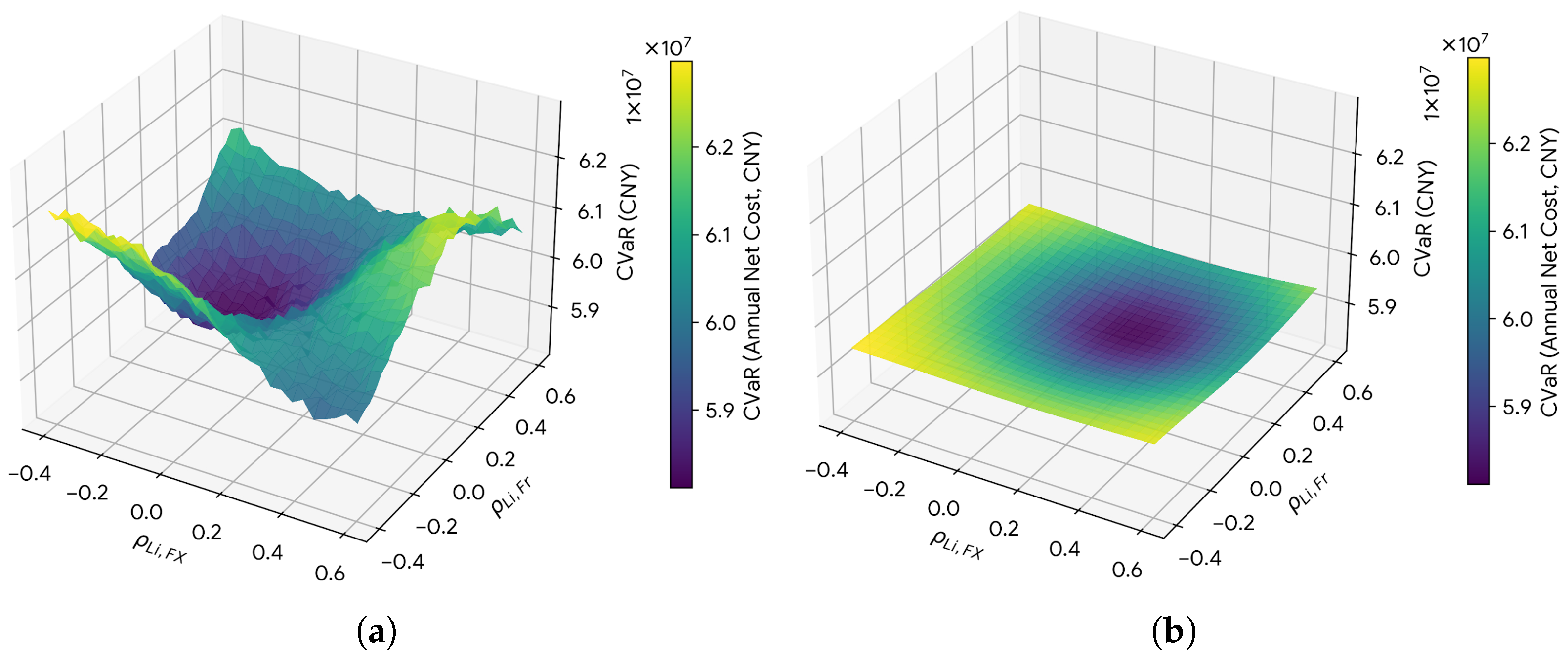

Figure 8.

A 3D comparison of risk surfaces under correlation drift: (a) The continuous benchmark exhibits sharp ridges and steep gradients, indicating high sensitivity to correlation parameters. (b) The proposed discrete strategy exhibits a flat, robust plateau, indicating stability against parameter mis-specification.

Figure 8.

A 3D comparison of risk surfaces under correlation drift: (a) The continuous benchmark exhibits sharp ridges and steep gradients, indicating high sensitivity to correlation parameters. (b) The proposed discrete strategy exhibits a flat, robust plateau, indicating stability against parameter mis-specification.

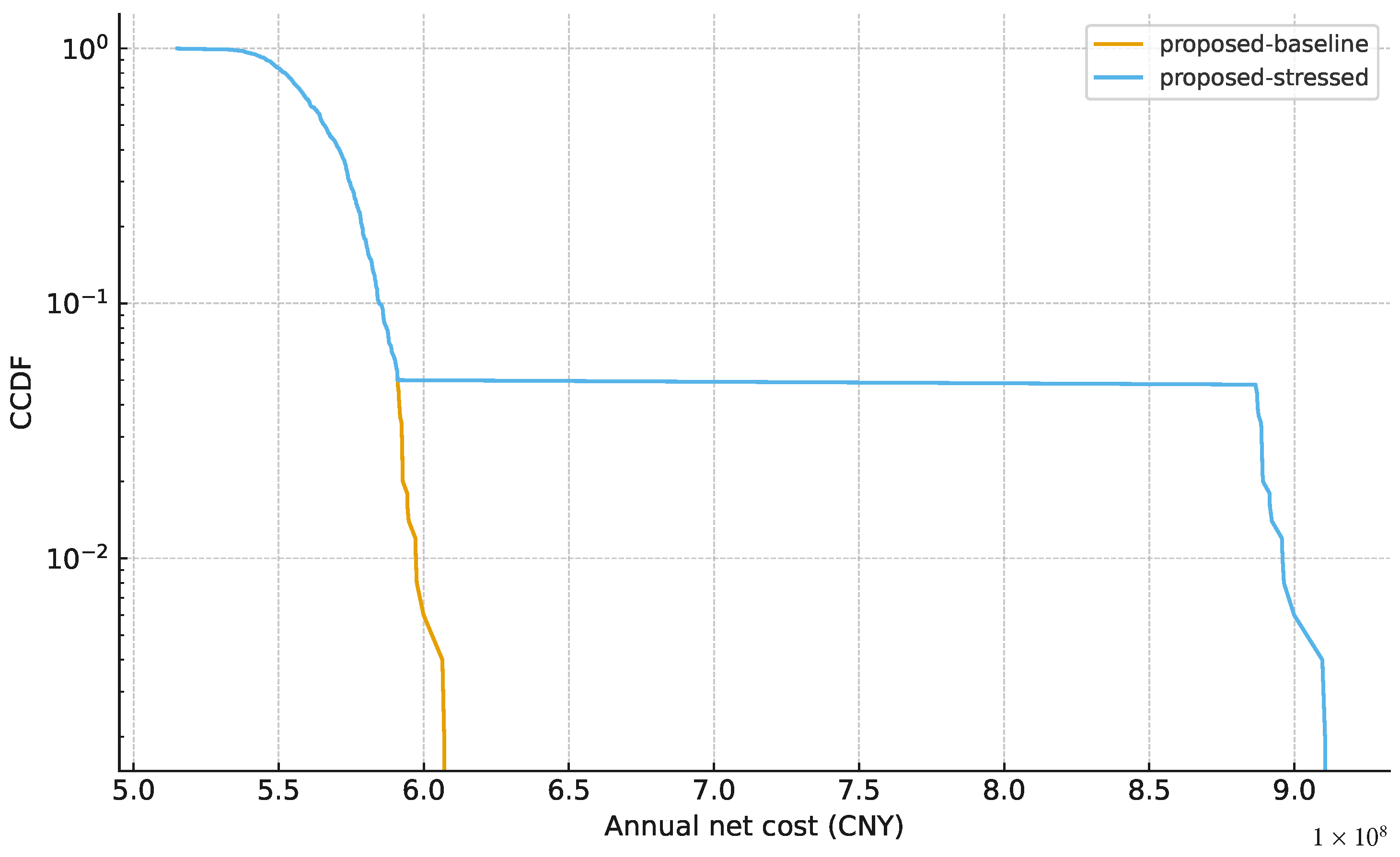

Figure 9.

Extreme-tail amplification dynamics under market stress. The Complementary CDF (log-scale) compares the tail risk of the proposed strategy under calibrated baseline conditions (orange) versus a stressed scenario involving simultaneous shocks and correlation breakdown (blue). Observe the distinct “plateau” in the stressed curve (blue), which extends significantly into the high-cost region (> CNY). This visualises the “tail amplification” effect: while the baseline probability of extreme loss decays rapidly, structural stress creates a “heavy tail” of extreme outcomes. This gap between the curves quantifies the additional liquidity buffer required to survive systemic shocks when market correlations fail.

Figure 9.

Extreme-tail amplification dynamics under market stress. The Complementary CDF (log-scale) compares the tail risk of the proposed strategy under calibrated baseline conditions (orange) versus a stressed scenario involving simultaneous shocks and correlation breakdown (blue). Observe the distinct “plateau” in the stressed curve (blue), which extends significantly into the high-cost region (> CNY). This visualises the “tail amplification” effect: while the baseline probability of extreme loss decays rapidly, structural stress creates a “heavy tail” of extreme outcomes. This gap between the curves quantifies the additional liquidity buffer required to survive systemic shocks when market correlations fail.

Figure 10.

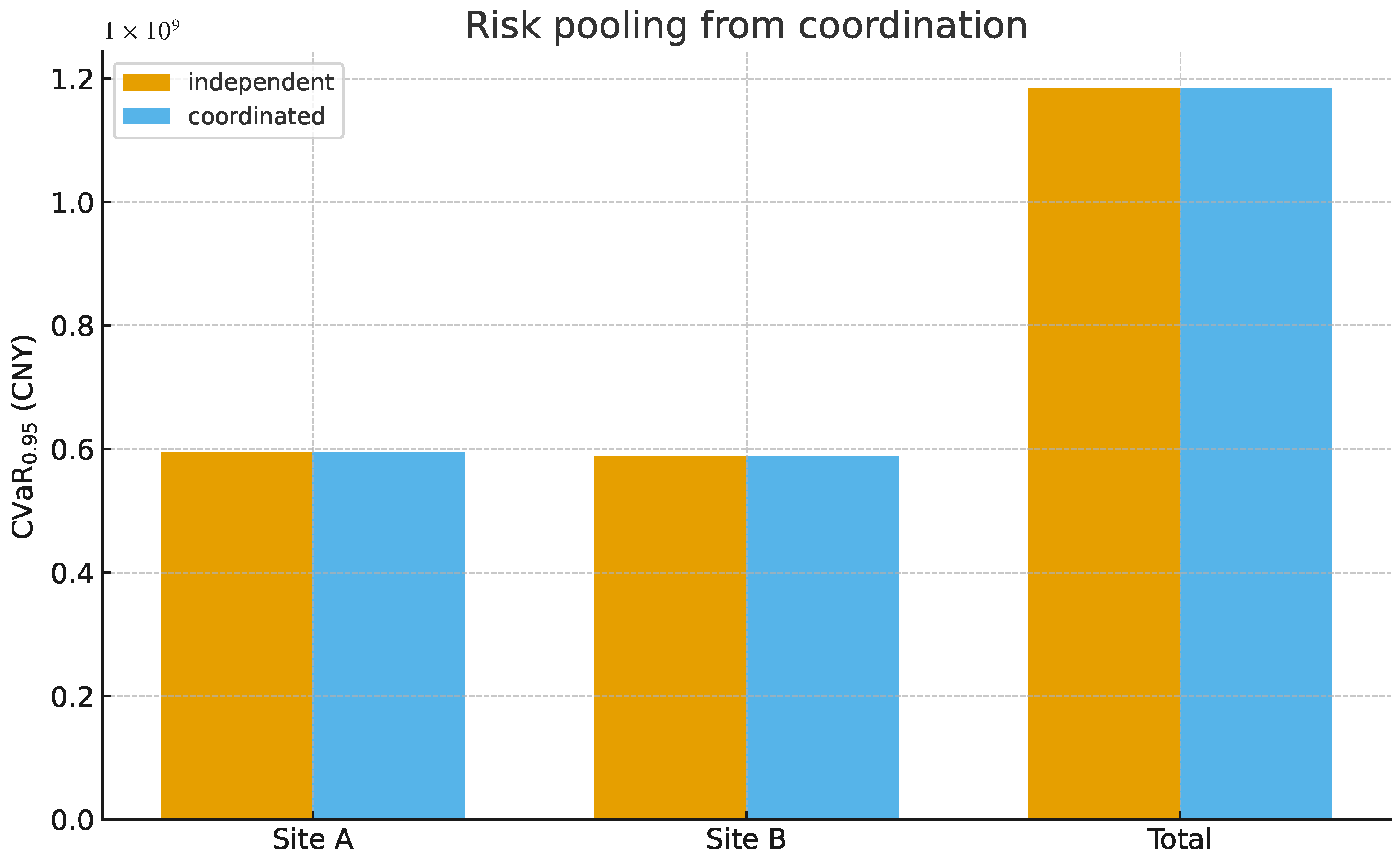

Cross-facility risk pooling: Independent vs. Coordinated Discrete Hedging. The bar chart compares the 95% Conditional Value-at-Risk () for two individual facilities (Site A, Site B) and their aggregated total (Right) under independent (orange) and coordinated (blue) strategies. Observe that, while local risks at Site A and B remain comparable across strategies, the Coordinated strategy optimises the Total group-level exposure. By imposing cross-facility constraints, the discrete model enforces “internal diversification,” preventing scenarios where both facilities simultaneously lock in expensive hedges during transient shocks. This demonstrates that decentralised coordination can stabilise the aggregate corporate outcome without sacrificing local flexibility.

Figure 10.

Cross-facility risk pooling: Independent vs. Coordinated Discrete Hedging. The bar chart compares the 95% Conditional Value-at-Risk () for two individual facilities (Site A, Site B) and their aggregated total (Right) under independent (orange) and coordinated (blue) strategies. Observe that, while local risks at Site A and B remain comparable across strategies, the Coordinated strategy optimises the Total group-level exposure. By imposing cross-facility constraints, the discrete model enforces “internal diversification,” preventing scenarios where both facilities simultaneously lock in expensive hedges during transient shocks. This demonstrates that decentralised coordination can stabilise the aggregate corporate outcome without sacrificing local flexibility.

Figure 11.

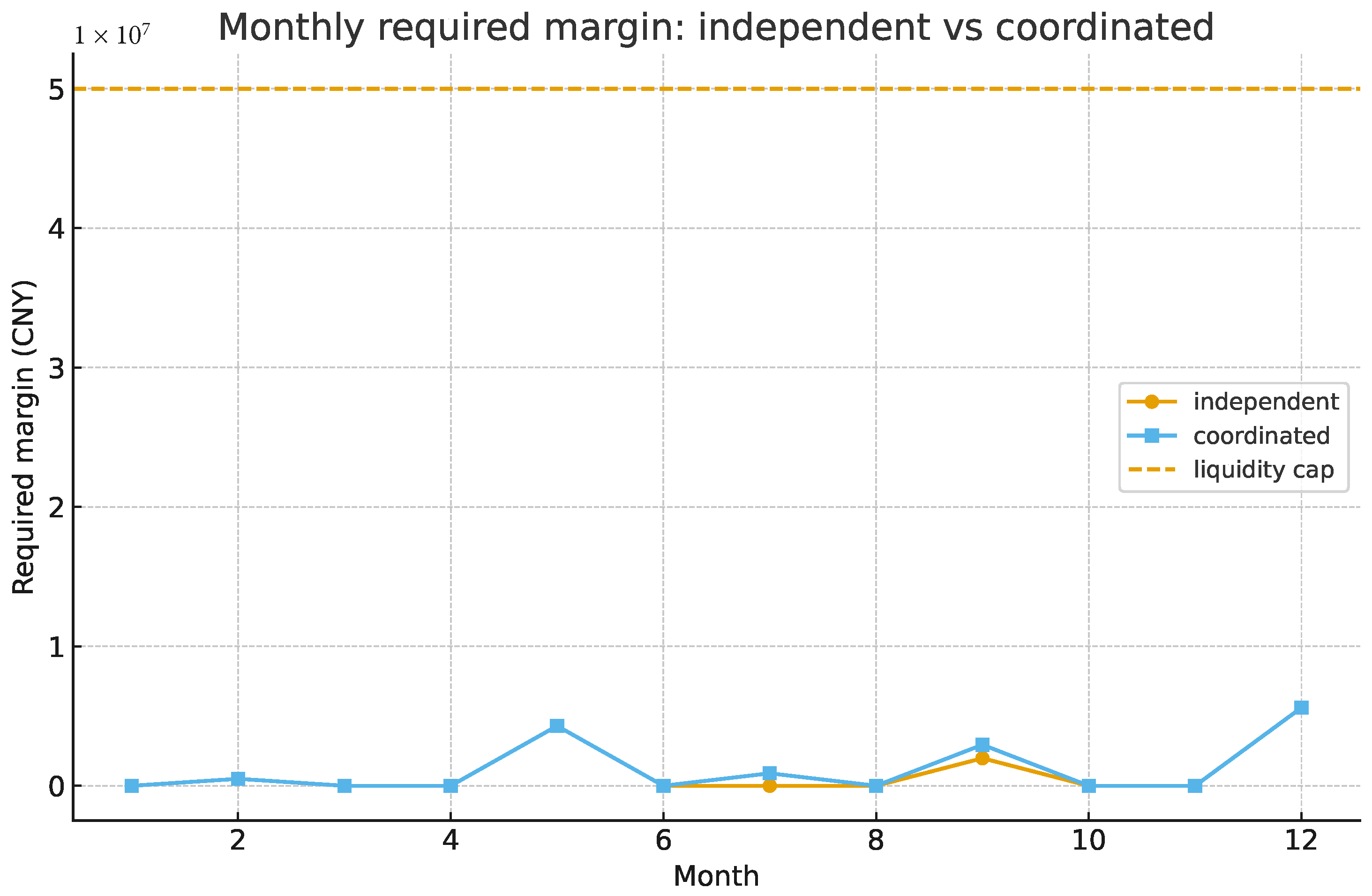

Monthly margin requirement dynamics: Independent vs. Coordinated Hedging. The time-series compares the liquidity outflows (margin calls) required by the Independent strategy (orange) and the Coordinated strategy (blue) against a corporate liquidity cap (yellow dashed). Observe that the Coordinated strategy helps smooth the liquidity demand trajectory. Mechanistically, the discrete coordination constraints prevent simultaneous “long-short” switching across facilities, thereby reducing the volatility of aggregate margin calls. This ensures that the firm’s hedging activities do not trigger unexpected liquidity crises, keeping funding needs predictably low and well within the established capital buffer.

Figure 11.

Monthly margin requirement dynamics: Independent vs. Coordinated Hedging. The time-series compares the liquidity outflows (margin calls) required by the Independent strategy (orange) and the Coordinated strategy (blue) against a corporate liquidity cap (yellow dashed). Observe that the Coordinated strategy helps smooth the liquidity demand trajectory. Mechanistically, the discrete coordination constraints prevent simultaneous “long-short” switching across facilities, thereby reducing the volatility of aggregate margin calls. This ensures that the firm’s hedging activities do not trigger unexpected liquidity crises, keeping funding needs predictably low and well within the established capital buffer.

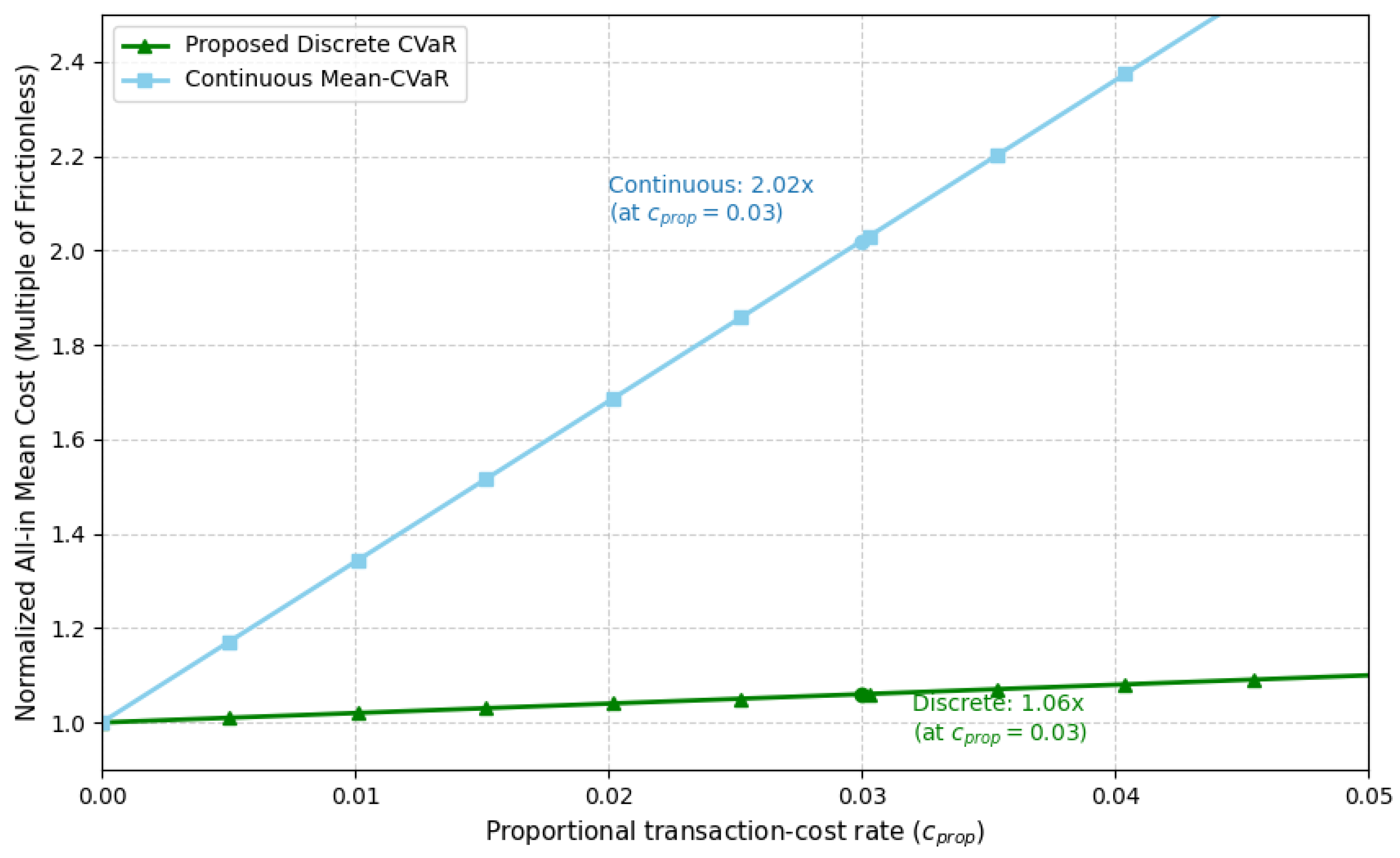

Figure 12.

All-in v transaction-cost rate under a 30% margin haircut. All values are expressed as multiples of the corresponding frictionless Case II mean cost.

Figure 12.

All-in v transaction-cost rate under a 30% margin haircut. All values are expressed as multiples of the corresponding frictionless Case II mean cost.

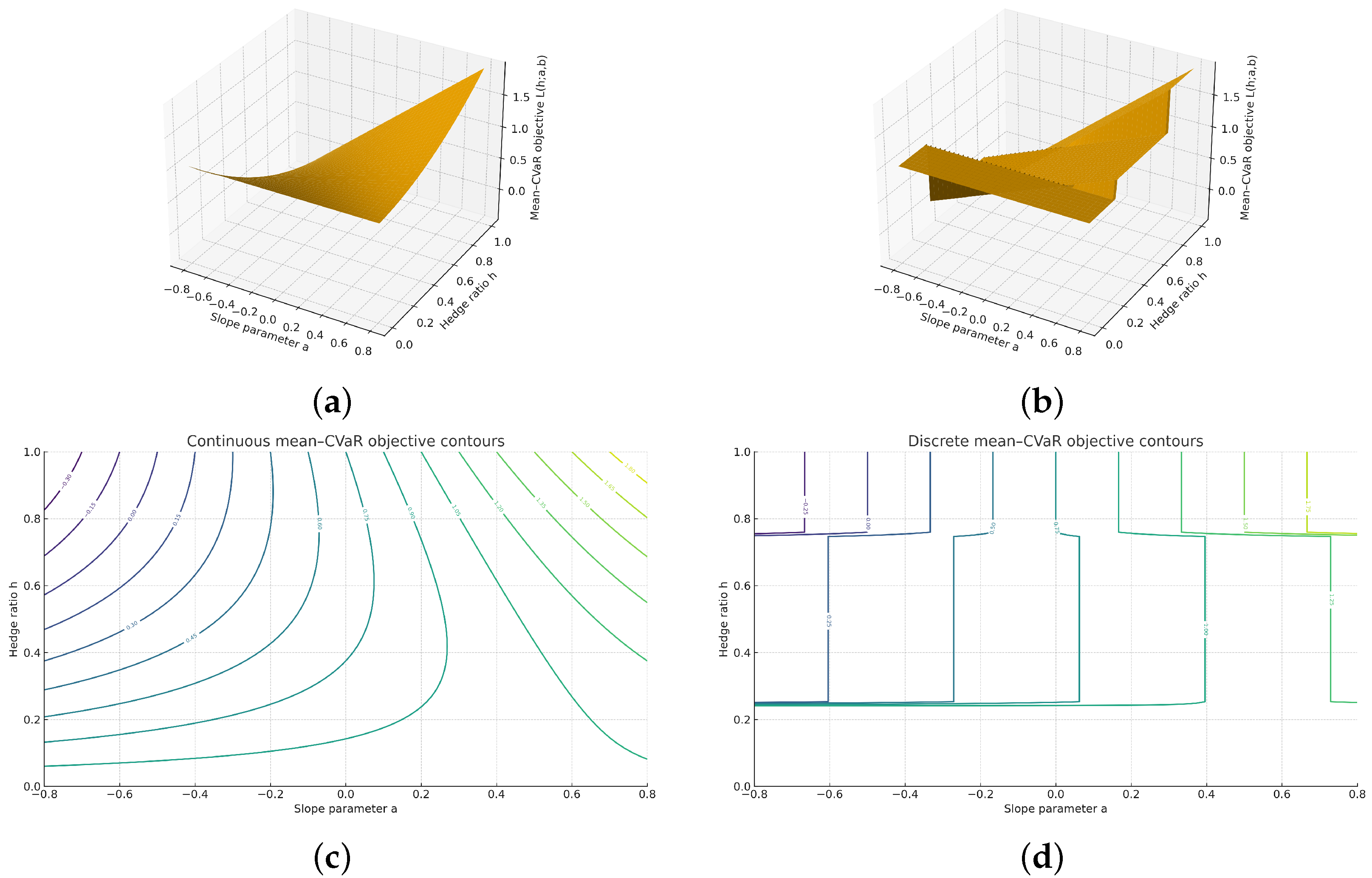

Figure 13.

One-factor toy model illustrating continuous vs. discrete mean–CVaR hedging: Panel (a) shows the continuous mean–CVaR objective as a function of h and a for fixed b; panel (b) shows the corresponding discrete optimum when h is restricted to the grid . Panels (c,d) display the corresponding contour maps (top-down views) for the continuous and discrete cases, respectively, where the color gradient represents the magnitude of the objective function value J.

Figure 13.

One-factor toy model illustrating continuous vs. discrete mean–CVaR hedging: Panel (a) shows the continuous mean–CVaR objective as a function of h and a for fixed b; panel (b) shows the corresponding discrete optimum when h is restricted to the grid . Panels (c,d) display the corresponding contour maps (top-down views) for the continuous and discrete cases, respectively, where the color gradient represents the magnitude of the objective function value J.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of Case Study I mean cost, , and to the copula specification for the joint lithium–freight risk factor.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of Case Study I mean cost, , and to the copula specification for the joint lithium–freight risk factor.

| Copula Specification | | | Mean Cost (CNY) | (CNY) | (CNY) |

|---|

| Gaussian copula | – | 0.00 | | | |

| t-copula () | 9.0 | 0.14 | | | |

| t-copula (baseline) | 7.1 | 0.18 | | | |

| t-copula () | 5.7 | 0.22 | | | |

Table 2.

Performance comparison under stochastic scenarios.

Table 2.

Performance comparison under stochastic scenarios.

| Strategy | Objective | Mean Cost (CNY) | CVaR0.95 (CNY) |

|---|

| No hedge | | | |

| Full hedge | | | |

| OLS-grid | | | |

| Continuous mean–CVaR hedge | | | |

| Proposed discrete CVaR | | | |

Table 3.

Execution statistics: number of hedge switches per factor.

Table 3.

Execution statistics: number of hedge switches per factor.

| Strategy | FX | Li | Freight | Total |

|---|

| Full hedge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OLS-grid | 12 | 10 | 9 | 31 |

| Continuous mean–CVaR hedge | 11 | 11 | 9 | 31 |

| Proposed discrete CVaR | 5 | 6 | 4 | 15 |

Table 4.

Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for mean annual cost and in Case Study I.

Table 4.

Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for mean annual cost and in Case Study I.

| Strategy | Mean Cost (95% CI, CNY) | CVaR0.95 (95% CI, CNY) |

|---|

| No hedge | [, ] | [, ] |

| Full hedge | [, ] | [, ] |

| OLS-grid | [, ] | [, ] |

| Continuous mean–CVaR hedge | [, ] | [, ] |

| Proposed discrete CVaR hedge | [, ] | [, ] |

Table 5.

Summary of robustness under stress scenarios.

Table 5.

Summary of robustness under stress scenarios.

| Stress Type | Stress Dimension | Effect on Mean Cost (Relative to Case I Baseline) | Effect on CVaR0.95 (Relative to Case I Baseline) | Qualitative Robustness Property |

|---|

| Parameter drift | Regression coefficients | Moderate change | Mild increase | Flat CVaR plateau under discrete hedge |

| Correlation stress | Li–Fr dependence | Small change | Mild increase | Convex risk basin around empirical correlation |

| Extreme-tail amplification | Joint shocks | Moderate change | Large reduction | Reduced joint tail clustering under coordination |

| Cross-facility pooling | Heterogeneous exposures | Small change | Mild reduction | Internal diversification through discrete coupling |

Table 6.

Impact of transaction costs and margin haircuts on mean all-in cost and all-in tail risk in the two-facility Case II (values relative to corresponding frictionless Case II outcomes).

Table 6.

Impact of transaction costs and margin haircuts on mean all-in cost and all-in tail risk in the two-facility Case II (values relative to corresponding frictionless Case II outcomes).

| Strategy | | Mean All-in Cost | (All-in) | Total Hedge Switches (per Year) | Margin-Call Months (per Mear) |

|---|

| Discrete CVaR (two-facility) | 0.03 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 18 | 2.0 |

| Continuous CVaR | 0.03 | 2.02 | 1.75 | 40 | 7.5 |

Table 7.

Liquidity stress measures under a 30% margin haircut in the two-facility Case II, relative to the frictionless Case II benchmark.

Table 7.

Liquidity stress measures under a 30% margin haircut in the two-facility Case II, relative to the frictionless Case II benchmark.

| Strategy | Peak Monthly Net Margin Outflow/Baseline Monthly Cost | 95%-CVaR of Cumulative Margin Top-Ups (Share of Annual Budget) | Probability of at Least One Margin Call | Average Number of Margin Calls per Year |

|---|

| Discrete CVaR (two-facility) | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 2.1 |

| Continuous CVaR | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.62 | 7.4 |