1. Introduction

Production planning is a critical component of sawmill operations, especially in countries such as Chile, where the forestry sector is both an important economic driver and subject to increasing environmental and social sustainability demands [

1,

2]. Despite this, many sawmills continue to rely on predefined and inflexible log cutting patterns derived from historical and empirical practices, which do not adequately reflect variations in product demand or the characteristics of the available raw material [

3].

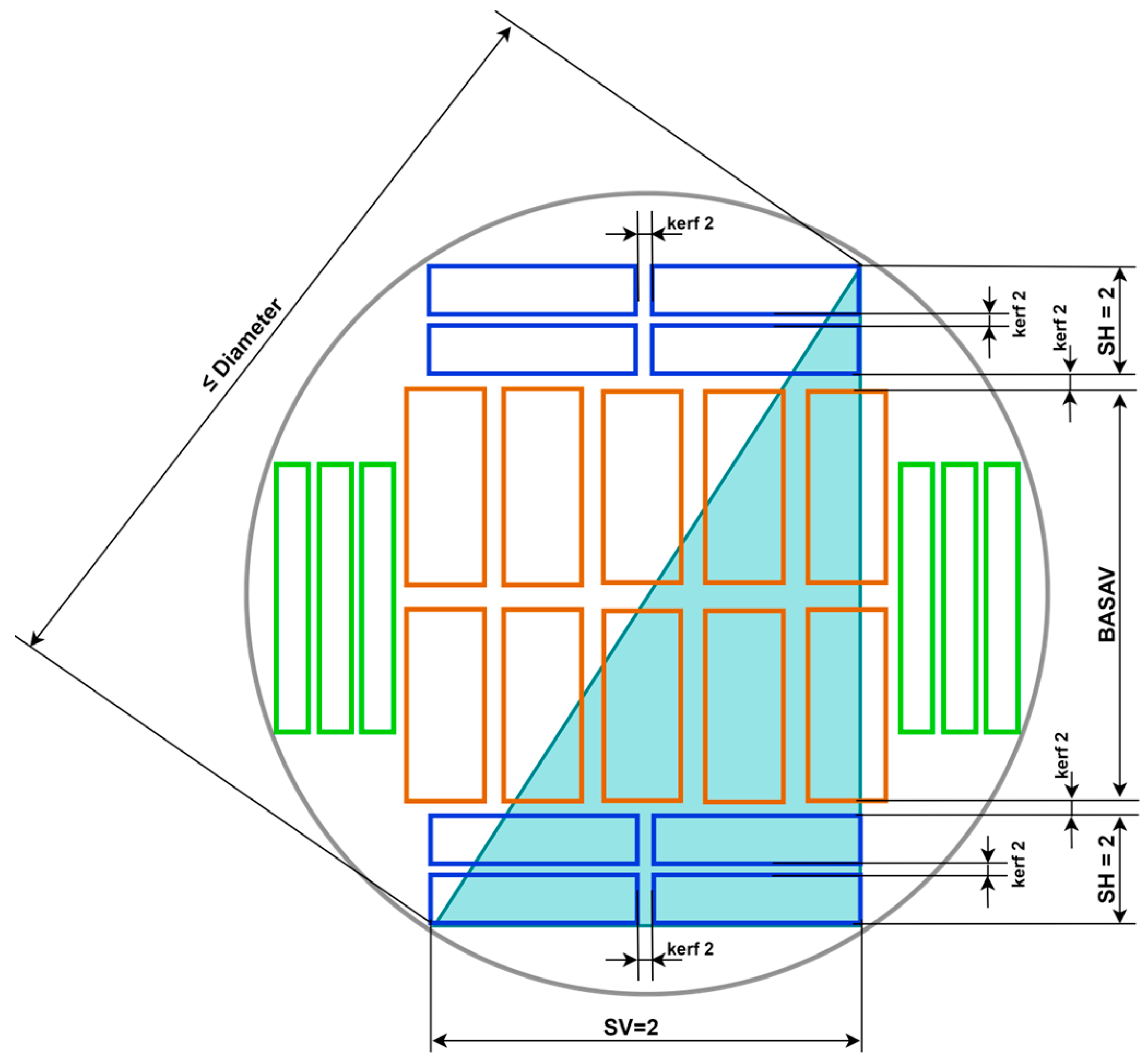

To illustrate this type of configuration,

Figure 1 shows a representative log cutting pattern, where P1, P2, and P3 denote the primary sawn products obtained from the cut. This geometric arrangement serves as the conceptual foundation for the new pattern variants generated in this study, which are designed to better align with sustainability-oriented tactical planning criteria.

Although patterns such as the one in

Figure 1 are technically feasible, using them statically in changing operational contexts can lead to misalignment between planning decisions and actual production conditions, resulting in overproduction, inefficient log utilization, and high volumes of wood residues, all of which undermine profitability and sustainability [

4,

5,

6]. To address these limitations, we develop optimization models that generate cutting patterns adapted to current planning conditions by directly incorporating product demand and log supply. Specifically, we propose two models and a column-generation algorithm that construct flexible cutting configurations aligned with key tactical criteria-resource efficiency, supply-demand balance, and residue reduction [

7,

8]. This approach provides a level of adaptability beyond traditional methods and supports more sustainable tactical decision making in sawmills.

The main motivation for this study, along with its scientific contributions, can be summarized as follows:

A dynamic pattern-generation framework based on column generation, capable of producing cutting configurations that adapt to log availability and product-demand conditions, thereby overcoming the rigidity of the static pattern libraries commonly used in previous studies.

Explicit integration of sustainability-oriented tactical criteria (such as raw-material efficiency, overproduction control, and residue reduction), addressing a critical gap in the literature, where such sustainability dimensions are rarely included in cutting-pattern design.

A Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Programming (MIQCP)-based geometric model that generates new cutting patterns for each diameter class using geometric constraints, improving upon previous approaches that rely on heuristic or pre-generated patterns.

A unified framework that links supply, demand, sustainability-oriented tactical criteria and geometric feasibility, offering greater adaptability than traditional models that rely on fixed cutting configurations.

Validation using industrial benchmark data (including 160 real cutting patterns and realistic supply–demand matrices), providing practical relevance that is seldom achieved in prior studies.

A comparative evaluation of alternative functions objective formulations, enabling the analysis of how different tactical criteria (log minimization, residue minimization, overproduction reduction, and production maximization), affect system performance, an aspect not examined in previous studies.

The literature can be broadly divided into two groups: studies that rely on predefined cutting patterns and those that generate patterns during the solution process. In the first group, static pattern allocation has been addressed through linear programming, heuristics, and simulation. Palma and Vergara [

9] propose a multi-objective model with uncertain preferences, using robust linear programming to select cutting patterns under criteria related to cost, wood residues, and overproduction. Parra Gálvez et al. [

10] combine pre-generated patterns by diameter class with a MILP assignment model; their cant-sawing configuration improves material utilization and reduces overproduction through its dynamic integration with weekly planning.

Ramos-Maldonado et al. [

11] propose a multi-objective MILP that jointly minimizes volume loss and overproduction in small- and medium-sized sawmills, using 160 static patterns together with real log availability and weekly demand matrices; we use this dataset as a benchmark for validation and comparison in our study. Maturana et al. [

12] compare a field heuristic with a generalized lot-sizing MILP and show that the MILP achieves superior demand fulfillment and more efficient use of raw material. In a related experimental study, Vilkovský et al. [

13] examine classical cutting schemes (cant, radial, and tangential) for beech, although without incorporating dynamic optimization.

At smaller operational scales, Câmpu and Derczeni [

14] analyze a manually fed, low-capacity sawmill and highlight its strong reliance on traditional cutting patterns. Todoroki and Rönnqvist [

15], as well as Todoroki [

16], use dynamic programming to integrate primary and secondary breakdown processes with internal defect information, although their approaches do not dynamically modify cutting patterns. Thomas and Buehlmann [

17,

18] quantify the effects of sawing variation (SV): LORCAT simulations show increases of up to 4% in volume recovery and the production of one additional board for larger logs, which can translate into gains of up to USD 336,000 per year for a medium-sized sawmill.

A second line of research focuses on generating cutting patterns during the solution process, sometimes using column-generation techniques. Novak [

19] proposes an early two-component architecture consisting of a heuristic pattern generator by diameter class and a primary assignment model, which is useful when diameter classes allow the design to be modularized without excessive computational effort. Herrera-Medina and Leal-Pulido [

20] adopt a two-stage approach: an integer programming model first produces class-specific optimal patterns, followed by a fractional allocation to meet demand, achieving approximately 75% utilization and 25% waste under idealized conditions.

Acevedo et al. [

5] combine computerized scanning with dynamic programming to generate optimal 3D cutting patterns for radiata pine logs with internal defects, maximizing both yield and net profit. Forghani et al. [

21] propose a flexible system that produces multiple alternative patterns per log and selects the best option using a set-packing model. Vanzetti et al. [

22] exhaustively pre-generate patterns but organize their framework into two modules that can be extended to dynamic pattern generation, a useful feature under volatile demand and inventory conditions. Pradenas et al. [

4] model circular cutting patterns, distinguishing central and lateral zones, using a MIP combined with genetic algorithms and simulated annealing to generate candidate patterns, which are later evaluated with CPLEX to reduce material losses. McPhalen [

23] presents an early dynamic approach based on Dantzig–Wolfe decomposition and dynamic programming to evaluate cutting strategies according to market prices and log profiles. Nordmark and Oja [

24] apply PLS methods to predict cutting value from 3D optical and X-ray scans of Swedish pine; although not a dynamic generation method, their work supports the development of value-driven adaptive cutting systems.

Other studies place a stronger emphasis on operational considerations and sustainability. Manhiça et al. [

25,

26,

27] compare conventional and programmed breakdown strategies for

Pinus spp. in small-scale mills using predefined diameter-class models; employing MaxiTora-designed patterns, they measure output in terms of volume per operator per shift. Programmed breakdown yields lower average efficiency (8.07 vs. 10.18 m

3/operator/shift), a result attributed to limited operator experience; however, with adequate training, programmed approaches can improve accuracy and material utilization [

27]. Kozakiewicz et al. [

28] show that appropriate pattern design can reduce material losses associated with both technology constraints and log quality. Hinostroza et al. [

29] address the problem of packing rectangles into circular sections using a MINLP for small instances and metaheuristics, such as simulated annealing, for larger ones; their geometric framework offers a useful complement to structured optimization models for pattern design. Carreiro et al. [

30] compare volumetric yield and energy consumption across cutting models in portable mills and demonstrate that the choice of pattern directly influences process efficiency.

At the supply-chain level, Fuentealba et al. [

3] integrate forest harvesting and sawmill production using a MILP model combined with column generation. Their approach includes a subproblem that dynamically determines bucking rules based on the dual information from the primary problem, improving tree-to-product allocation under multiple operational constraints. This is conceptually aligned with the work of Maness and Adams [

31], who link bucking and sawing decisions through linear programming and a Dantzig–Wolfe decomposition variant, demonstrating economic gains through iterative feedback. Maness and Norton [

32] extend this idea to a multi-period planning framework that incorporates production, inventory, and raw-material decisions under dynamic market conditions. Related contributions by Novak [

19] and Herrera-Medina and Leal-Pulido [

20] also implement allocation algorithms for sawmill cutting, although without using dual prices or a formal decomposition structure.

Many existing approaches rely on predefined pattern sets or on partial generation schemes that are not fully embedded within formal optimization frameworks, and only a few combines pattern generation with explicit supply-demand control through column generation. This gap motivates the development of a formulation that incorporates tactical sustainability criteria while remaining solvable through exact optimization methods.

In recent years, several contributions have advanced cutting and sawing optimization in the wood-processing industry. Forghani et al. [

21] propose a flexible sawing and product-grading methodology based on CT-scanned log models, in which a mixed-integer optimization phase selects cutting configurations that maximize value yield while accounting for wane and log-shape constraints. Their work illustrates the potential of optimization to exploit internal log information beyond traditional cant-sawing approaches. Other authors have emphasized the influence of log geometry and process variability on yield and recovery. Thomas and Buehlmann [

17] quantify the impact of sawing variation on hardwood lumber recovery under industrial conditions, while Cataldo et al. [

33] show that geometric defects—including taper, sweep, and eccentricity—significantly affect sawing efficiency in Mediterranean hardwood logs, with taper emerging as a dominant predictor of recovery. Together with recent CT-based defect-detection and quality-assessment studies, these contributions underscore the importance of integrating geometric information, defect characterization, and optimization models when designing cutting patterns for modern sawmills.

Recent sustainability-oriented and supply-chain-aware studies have further expanded the scope of optimization in the sawmill and forest industries. Beach et al. [

34] introduce strengthened discretization techniques and hybrid separable relaxations for non-convex mixed-integer quadratically constrained programs (MIQCPs), improving tractability and solution quality in large-scale industrial planning problems and supporting the viability of MIQCP-based pattern generation in wood-processing contexts. Within the broader domain of supply-chain integration, Rodriguez et al. [

35] develop a comprehensive mixed-integer model that links forest harvesting, lumber production, and energy generation, demonstrating how coordinated optimization across stages can enhance both economic and environmental performance in timber-based value chains. Vergara et al. [

36] propose a production-planning heuristic for sawmill operations under demand variability and multi-product requirements, highlighting the practical importance of flexible cutting-pattern generation in modern industrial environments. Collectively, these advances reveal a clear trend: optimization frameworks in forestry are evolving from simple single-stage cutting or harvest-scheduling models toward integrated, multi-objective, multi-stage formulations that consider material use, demand fulfillment, energy, and sustainability criteria. This broader context reinforces the motivation for developing a dynamic pattern-generation model that connects tactical sawing decisions with log-utilization efficiency and supply–demand responsiveness.

From a methodological perspective, recent advances in mixed-integer nonlinear optimization have strengthened the foundation for solving complex industrial planning problems. Bagheri [

37] developed a convexified MIQCP formulation for the optimal operation of energy-storage systems with dynamic ratings, demonstrating that large nonlinear mixed-integer models can be solved efficiently to global optimality using modern optimization tools. Complementing this work, Bagheri et al. [

38] proposed an MIQCP-based multi-objective operational strategy for renewable-integrated distribution systems, showing the practical applicability of MIQCP models for multi-criteria decision making in real industrial environments. In the context of manufacturing optimization, Ma and Shao [

39] introduced an automatic cross-cutting optimization approach that combines computer vision with mixed-integer reasoning to improve cutting precision and material efficiency. Additional industrial contributions, such as the MILP-based capacity-configuration model by Güldorum et al. [

40], further illustrate the growing adoption of mixed-integer methods for large-scale resource-allocation and production-planning problems. Collectively, these advances highlight the suitability of MIQCP and related mixed-integer formulations for representing geometric feasibility relationships and for supporting the pricing subproblems required by column-generation frameworks in cutting-pattern optimization.

Despite these contributions, existing research on sawmill cutting optimization exhibits several important limitations. First, most approaches rely on predefined pattern sets and therefore lack the structural adaptability required to adjust cutting decisions in response to changes in product demand, log availability, or operating conditions. Second, sustainability-oriented criteria—such as minimizing wood residues, improving raw-material efficiency, and controlling overproduction—are rarely integrated explicitly into tactical decision-making models. Third, only a small number of studies validate their methods using industrial benchmark pattern libraries or realistic supply–demand matrices, which limits the practical relevance of their findings. These gaps highlight the need for a dynamic, sustainability-oriented pattern-generation framework that can incorporate industrial data, address tactical planning requirements, and produce cutting configurations consistent with real sawmill constraints.

In response to this gap, the present study develops a methodological framework for dynamically generating log cutting patterns in sawmills using an optimization approach based on column generation. The proposed models explicitly integrate log supply, product demand, and sustainability-oriented objectives to support tactical planning decisions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the mathematical models and the column-generation solution strategy.

Section 3 describes the computational experiments conducted under different objective functions.

Section 4 discusses the results and their implications for tactical sawmill planning. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this study and offers recommendations for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

This section introduces two optimization models and a column-generation algorithm designed to dynamically generate log cutting patterns in sawmills. The primary model, formulated as a mixed-integer linear program (MILP), integrates log supply and product demand, while the secondary model, a mixed-integer quadratically constrained program (MIQCP), generates new patterns guided by the dual prices of the relaxed primary model. Starting from a base set of industrial patterns, the column-generation algorithm iteratively incorporates efficient configurations to improve material utilization, reduce overproduction, and minimize residues. The following subsections describe the structure of the models, the column-generation strategy, and the computational experiments conducted to evaluate their performance under different tactical criteria and demand scenarios.

Before presenting the mathematical formulation, it is important to clarify the operational and geometric assumptions that underpin the proposed methodology. The model assumes that (i) logs within the same diameter class have homogeneous geometric quality, as defects and taper are not explicitly represented at the tactical level; (ii) the sawing process follows a fixed cant-type configuration with constant mechanical parameters and a uniform saw kerf; (iii) processing times, feed speeds, and machine schedules are not modeled, as these correspond to operational-level decisions; (iv) all products generated by a pattern must fit within the circular cross-section of the log, a condition enforced through quadratic geometric constraints in the MIQCP subproblem; (v) each cutting pattern includes at most one central cant product and symmetrically positioned lateral boards, consistent with standard industrial cant-sawing practices; and (vi) log availability and product demand are treated as deterministic inputs for the planning horizon.

2.1. Primary Mathematical Model

The formulation is based on a set of parameters and variables that represent the key features of the cutting process. The log cutting patterns

are modeled as vectors indicating the quantity of product

produced when applying pattern

to a given log (see

Figure 2). Each log class

is associated with a subset of compatible patterns,

, which reflects the geometric and operational constraints that determine its processability in the sawmill.

The parameter represents the portion of the original log volume that is not converted into sawn wood products when applying pattern , including residues such as sawdust, slabs, and off-spec pieces. In turn, denotes the unit volume of product , calculated from its physical dimensions (thickness, width, and length).

The model also incorporates constraints related to raw-material availability. For each diameter class , the parameter defines the available log volume, while the decision variable indicates the number of logs processed using pattern . Finally, the variable represents the overproduction of product , that is, the amount produced in excess of the established demand. This formulation allows for the evaluation of both raw-material utilization efficiency and the degree of alignment between production and demand under different tactical objectives.

The proposed mathematical model represents the product-generation process in a sawmill through the use of log cutting patterns, formulated as a mixed-integer programming model designed to operate within a column-generation framework. This approach enables the iterative construction of an efficient subset of cutting configurations, avoiding the need to pre-enumerate all possible patterns, whose number grows exponentially.

The structure of the model includes sets, parameters, and variables that represent the essential features of the cutting system, along with objective functions and constraints that guide the solution toward different tactical criteria. These components are formally described in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Appendix A lists all indexes, variables, and parameters in summary form.

The proposed primary mathematical model is formulated with sufficient flexibility to incorporate various tactical objectives relevant to the cutting process. Depending on the selected planning criterion, it can be oriented toward minimizing the total volume of logs used, reducing overproduction, or decreasing the amount of residues generated.

Below, we present the general structure of the model together with a baseline formulation that corresponds to the minimization of log usage. Alternative objective functions are described in the experiments section, where their impact on system performance is analyzed.

Equation (1) defines the objective function of the model, which minimizes the total number of logs processed in the system.

Equations (2) and (3) constitute feasibility constraints. Equation (2) is a supply constraint that limits the total volume of logs used in each diameter class according to the available resources in the sawmill. Equation (3) is a demand constraint that ensures that the total quantity of products generated for each type is sufficient to satisfy demand while allowing for possible overproduction .

Finally, Equations (4) and (5) define the domains of the model’s variables: the number of logs processed must be non-negative integers, whereas overproduction is represented by non-negative continuous quantities.

2.2. Secondary Mathematical Model

The secondary model is based on a cant-type sawing scheme, which is widely used in high-production sawmills due to its simple and symmetrical structure. Unlike radial or quality-oriented patterns, the cant pattern permits a regular geometric arrangement of central and lateral products, making it easier to represent through mathematical constraints. Moreover, it has proven effective for both pruned and unpruned logs and is particularly useful in contexts where operational yield and process stability are prioritized [

41]. These characteristics make it a robust and representative alternative for supporting sustainable tactical planning in industrial environments.

Building on this foundation, the secondary model dynamically generates a new cutting pattern for a log of a given diameter, guided by the dual prices obtained from the relaxed primary model. Its objective is to minimize the reduced cost while respecting the geometric constraints that define the arrangement of central and lateral products within the circular cross-section of the log. This structure, consistent with the logic of cant sawing, enables the identification of feasible cutting configurations that adapt dynamically to the tactical objectives defined by the planner.

The secondary problem is formulated as a mixed-integer quadratically constrained programming (MIQCP) because the geometric feasibility of each cutting pattern depends on nonlinear spatial relationships. Ensuring that the central cant and lateral boards fit within the circular log cross-section requires quadratic constraints derived from the Pythagorean theorem. These relationships cannot be captured accurately using linear models. Heuristic methods are fast but do not guarantee optimality. In contrast, the MIQCP formulation ensures geometric validity and supports optimal evaluation, making it the most suitable approach for the pricing subproblem.

The formulation includes sets, parameters, and variables that represent the essential features of the cutting system, together with the objective function and constraints. These components are formally described in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Objective function: Reduced cost of the generated pattern.

Equation (6) represents the objective function that minimizes the reduced cost of the proposed pattern. This function evaluates whether a new cutting pattern is beneficial in the context of the relaxed primary model. A pattern is added to the primary model only if its reduced cost is negative, indicating that it can improve the current solution. The dual prices associated with the supply constraints in Equation (2) are denoted by , while those associated with the demand constraints in Equation (3) are denoted by . The term denotes the quantity of product generated by the new pattern, and corresponds to the coefficient of the objective function used in the primary model.

Equations (7)–(11) ensure that the central product is activated only when the binary variable ; otherwise, its quantities and must be zero. Equation (11) enforces that only one central product can be active in each pattern. In other words, every pattern may contain at most a single type of central product.

- 2.

Geometric location constraint, based on the Pythagorean theorem:

Equation (12) ensures that the rectangular block formed by the central product and its cuts is located within the circular cross-section of the log, applying the Pythagorean theorem.

- 3.

Constraint on the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the central product:

Equations (13) and (14), although not strictly necessary, provide a linear constraint that represents an upper bound on the quantity of central product c that can be obtained.

- 4.

Determination of the dimensions of the central cant:

Equations (15) and (16) define the central cant as the maximum dimension occupied by the central products in the horizontal and vertical directions. This cant serves as a reference for placing the lateral products.

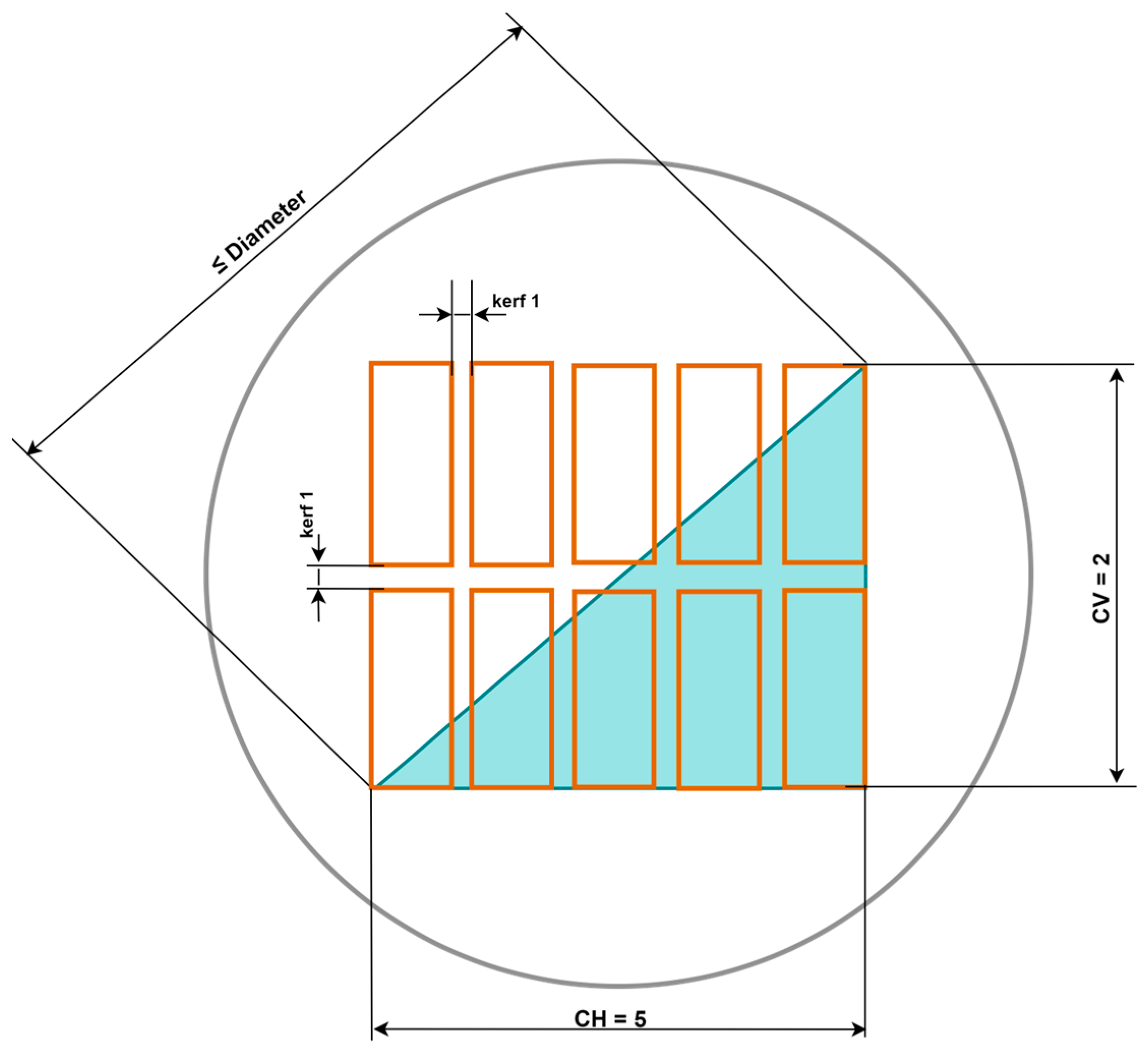

Figure 3 illustrates the rectangular arrangement of central products in the cross-section of the log, considering saw kerf margins (

kerf1) and validation through the Pythagorean theorem, used in Equation (12), to ensure location within the usable area.

Equations (17)–(20) allow each lateral product l to be activated only if . If it is not active, the corresponding quantities must be zero. Equation (21) restricts the solution to at most one type of lateral product active per pattern.

- 2.

Geometric constraint for lateral products, based on the Pythagorean theorem:

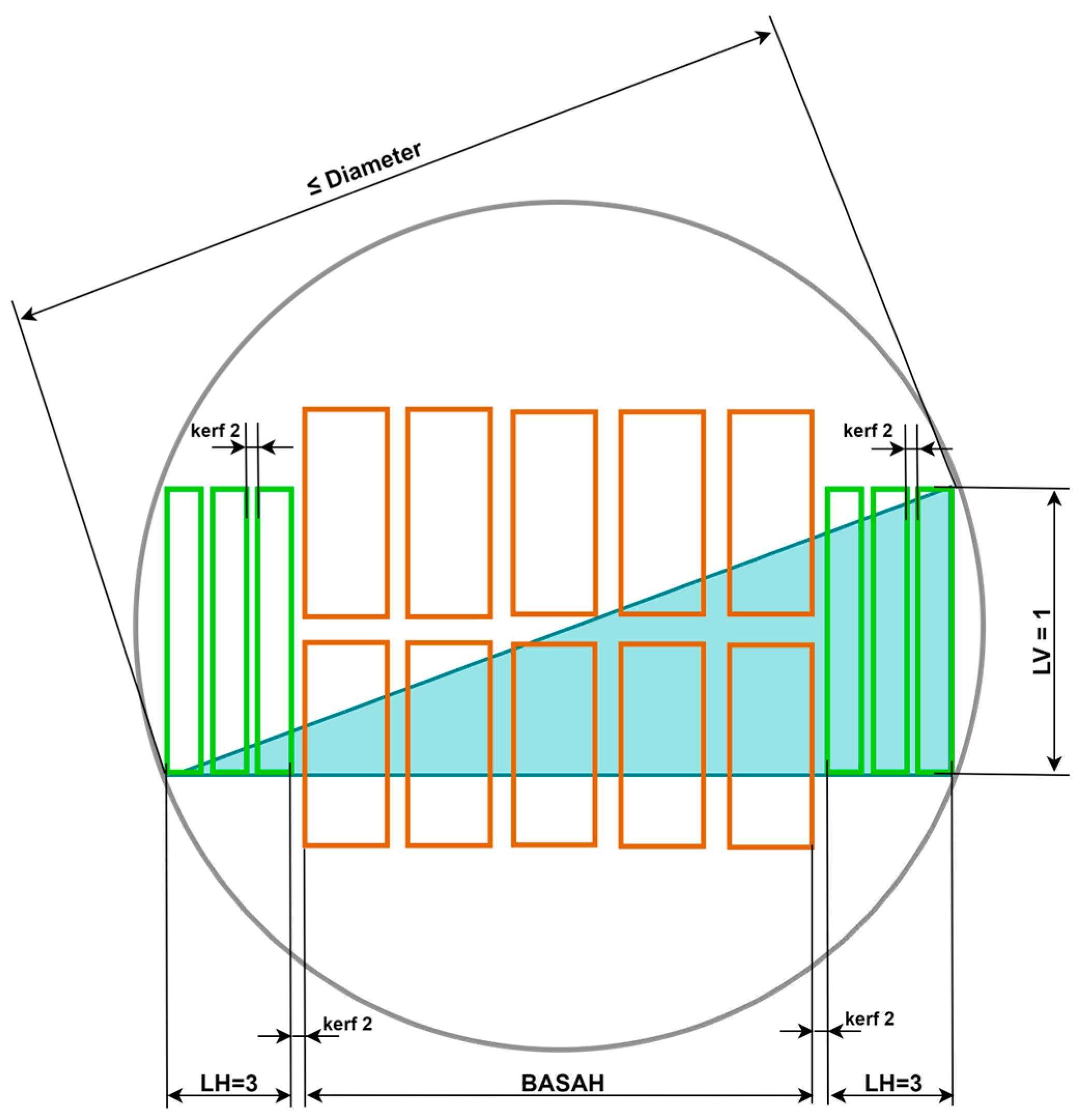

Equation (22) ensures that the arrangement of lateral products does not exceed the circular cross-section of the log. The resulting right-hand lateral product is assumed to be mirrored on the left.

- 3.

Constraint on the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the lateral product:

Equations (23) and (24), although not strictly necessary, provide a linear constraint that represents an upper bound on the quantity of lateral product l that can be obtained.

Figure 4 illustrates the symmetric placement of lateral products on both sides of the central cant (central products), using it as a geometric reference. The validity of product placement is ensured by the Pythagorean theorem used in Equation (22), which guarantees that the lateral pieces comply with the circular constraint imposed by the log’s geometry.

Equations (25)–(28) allow each upper lateral product l to be activated only if . If it is not active, the corresponding quantities must be zero. Equation (29) restricts the solution to at most one upper lateral product active per pattern.

- 2.

Geometric constraint for upper and lower lateral products, based on the Pythagorean theorem:

Equation (30) verifies that the upper lateral products (above the central product) are located within the circumference defined by the log diameter.

- 3.

Constraint on the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the upper and lower lateral products:

Equations (31) and (32), although not strictly necessary, provide a linear constraint that represents an upper bound on the quantity of upper lateral product l that can be obtained.

Figure 5 illustrates the complete arrangement of the generated pattern, after the symmetric placement of the upper and lower lateral products with respect to the central cant. Geometric validation is performed using the Pythagorean theorem, ensuring that all pieces are located within the circular cross-section of the log in accordance with the constraints of the secondary model.

Operational constraint on the first cut of upper lateral products:

Equation (33) establishes that the total width of the upper lateral products cannot exceed the horizontal dimension of the central cant.

Constraints for pattern determination:

Equations (34) and (35) calculate the quantity of products obtained according to the geometric variables of the model.

Equations (36)–(47) specify the nature of each variable in the model as dimensions, quantities, or binary variables.

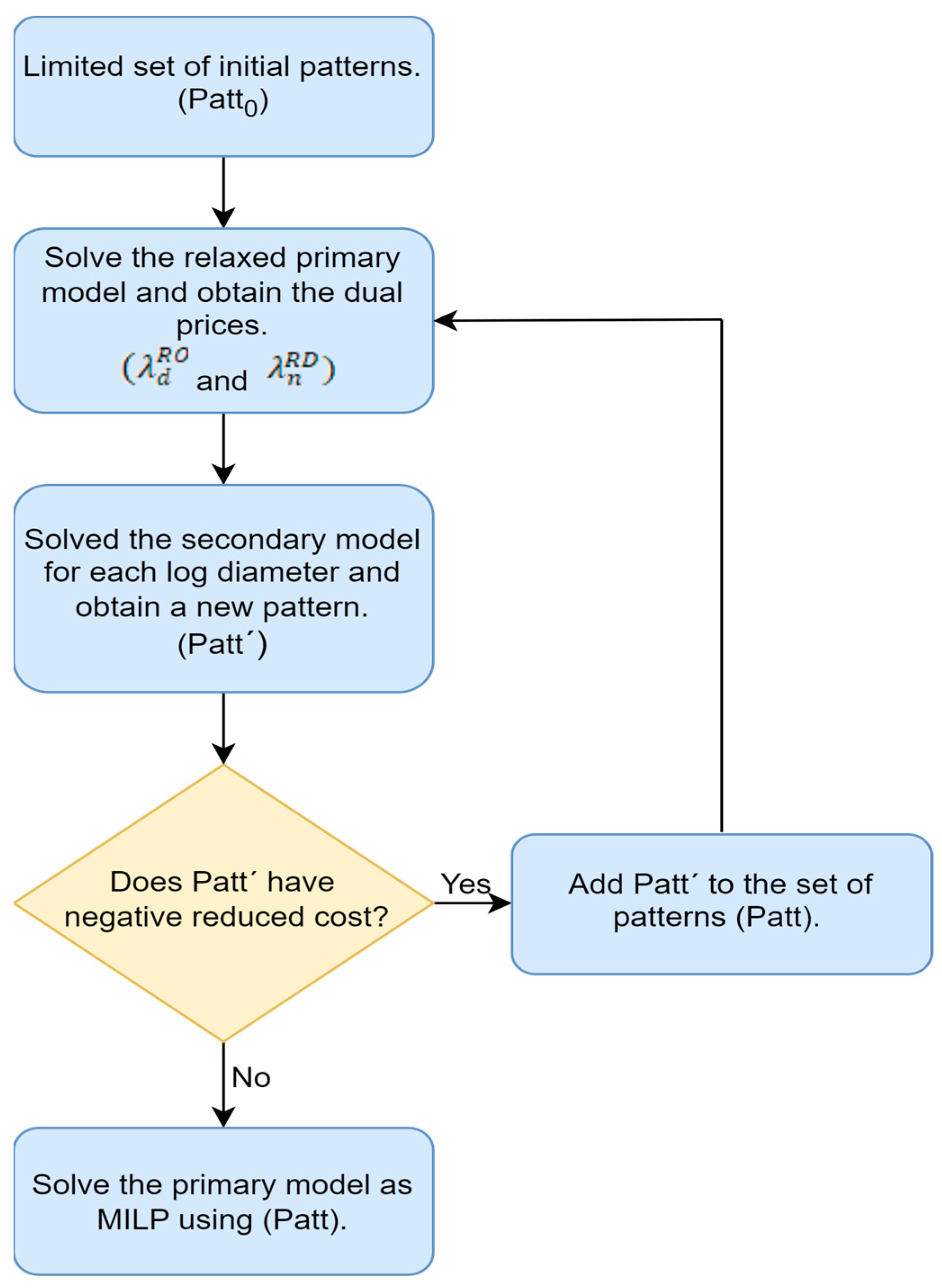

2.3. Solution Strategy: Column Generation

Since the number of log cutting patterns grows exponentially with the number of products, and thus with the number of variables in the primary problem, the proposed model is not solved using the complete set of patterns. Instead, a column generation strategy is employed to iteratively construct an efficient subset of log cutting patterns during the optimization process.

The procedure is based on the column generation method of Gilmore and Gomory [

42], in which the problem is structured into two stages:

The problem is initially solved over a limited set of log cutting patterns, usually trivial or historical ones. Although these initial patterns may or may not be efficient, they ensure model feasibility and serve as the starting point for the iterative process.

In each iteration, the secondary model uses the dual prices obtained from the relaxed primary mathematical model to determine whether a new cutting pattern exists that could improve the current solution. This is evaluated by computing the reduced cost of candidate patterns. If a pattern with negative reduced cost is found, it is incorporated into the set of log cutting patterns in the primary model. The process is repeated until no further improving patterns are identified.

Once no negative reduced-cost pattern exists, column generation stops and we fix the column set. We then solve the resulting integer primary mathematical model to optimality using a commercial MIP solver.

The secondary model was formulated based on log geometry constraints, using the Pythagorean theorem to locate the products within its circumference. The objective is to identify a combination of products that optimizes the objective function of the primary model while satisfying the sawing constraint of the sawmill.

Figure 6 schematically illustrates this procedure:

The column generation procedure is formally described in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Column Generation Procedure |

Input: Initial pattern set Patt0, supply and demand matrices

Output: Final pattern set Patt and how many times each one is used

1: Initialize Patt ← Patt0

2: Solve the relaxed primary model (LP)

3: while improving patterns are found do

4: Obtain dual prices (λdRo, λnRd) from the LP solution

5: for each diameter class d do

6: Solve the MIQCP subproblem using λ*

7: if a pattern with negative reduced cost is found then

8: Add the new pattern to Patt

9: end if

10: end for

11: end while

12: Solve the final primary model as a MILP using Patt |

This approach allows the solution to be iteratively refined, directing optimization toward reducing raw material consumption, minimizing overproduction, or decreasing residues, according to the established objective function. The column generation procedure incorporates the best cutting patterns, reducing the size of the model and the computing time required, without compromising the optimality of the relaxed primary model solution.

2.4. Computational Experiments

To evaluate the performance and flexibility of the proposed model, three computational experiments were designed to analyze its behavior under different conditions. Each experiment addressed a key dimension of the sawmill planning problem: the influence of different optimization criteria, the availability and use of log cutting patterns, and sensitivity to operational constraints.

In all cases, the model was initialized with the benchmark set of 160 industrial log cutting patterns published in Ramos-Maldonado et al. [

11], together with the original log availability (supply) and product demand matrices. These inputs, aimed at maximizing volumetric yield, represent the traditional approach adopted by the industry and constitute a valid baseline for evaluating improvements in efficiency, sustainability, and supply–demand balance.

The purpose of the experiments was to evaluate the convergence behavior and tactical performance of the proposed column-generation framework under different objective functions.

Before addressing the specific experiments, four independent objective functions were defined to optimize different aspects of the cutting process (Equations (48)–(51)):

z1: Minimization of the total volume of logs used, focused on material efficiency.

z2: Minimization of overproduction, oriented toward supply-demand balance.

z3: Minimization of the volume of residues generated, associated with sustainability objectives.

z4: Maximization of the total production volume, representing the classical strategy focused on volumetric yield.

Each of these functions will be used independently in the experiments, allowing us to observe their influence both on the model’s behavior and on the structure of the solutions generated.

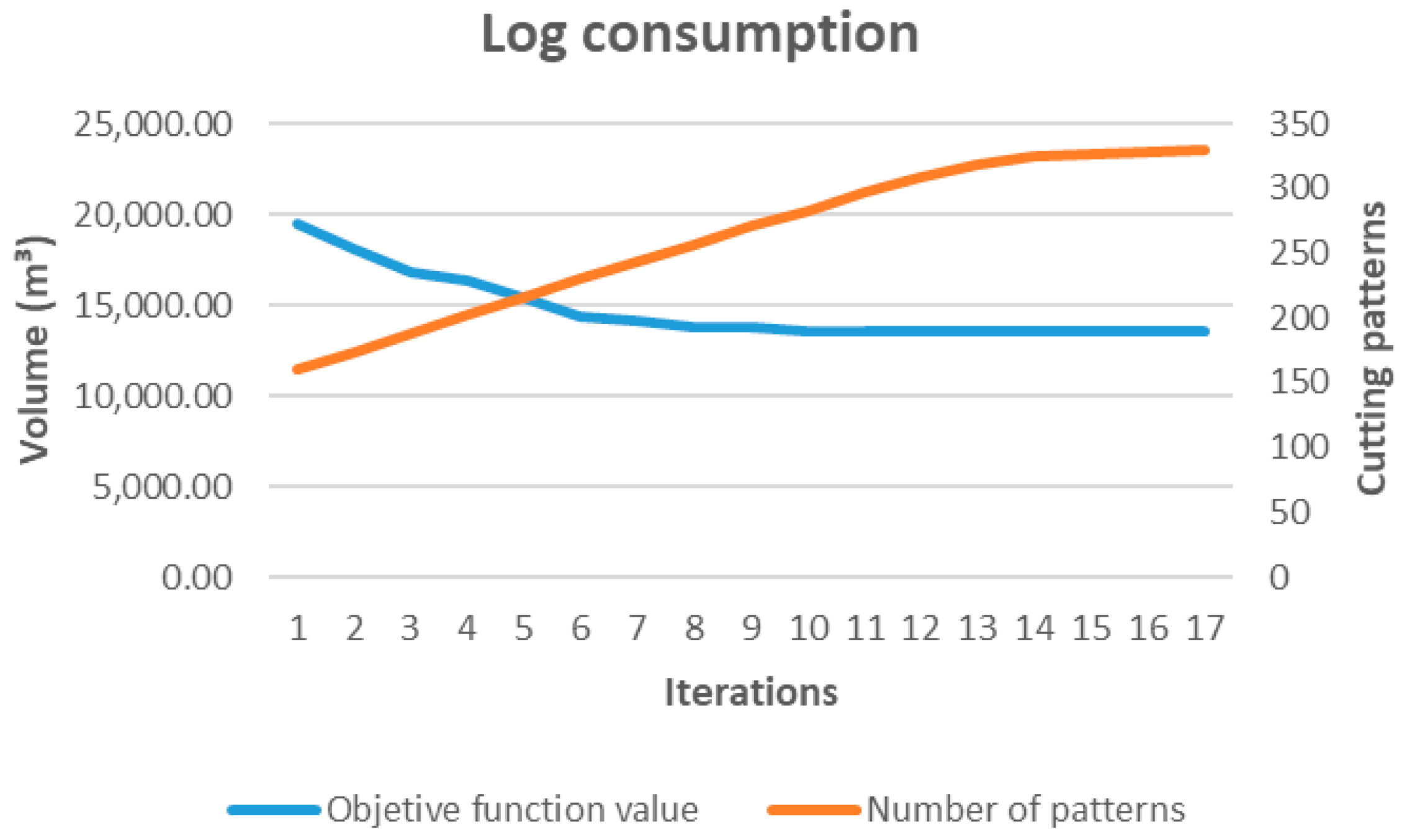

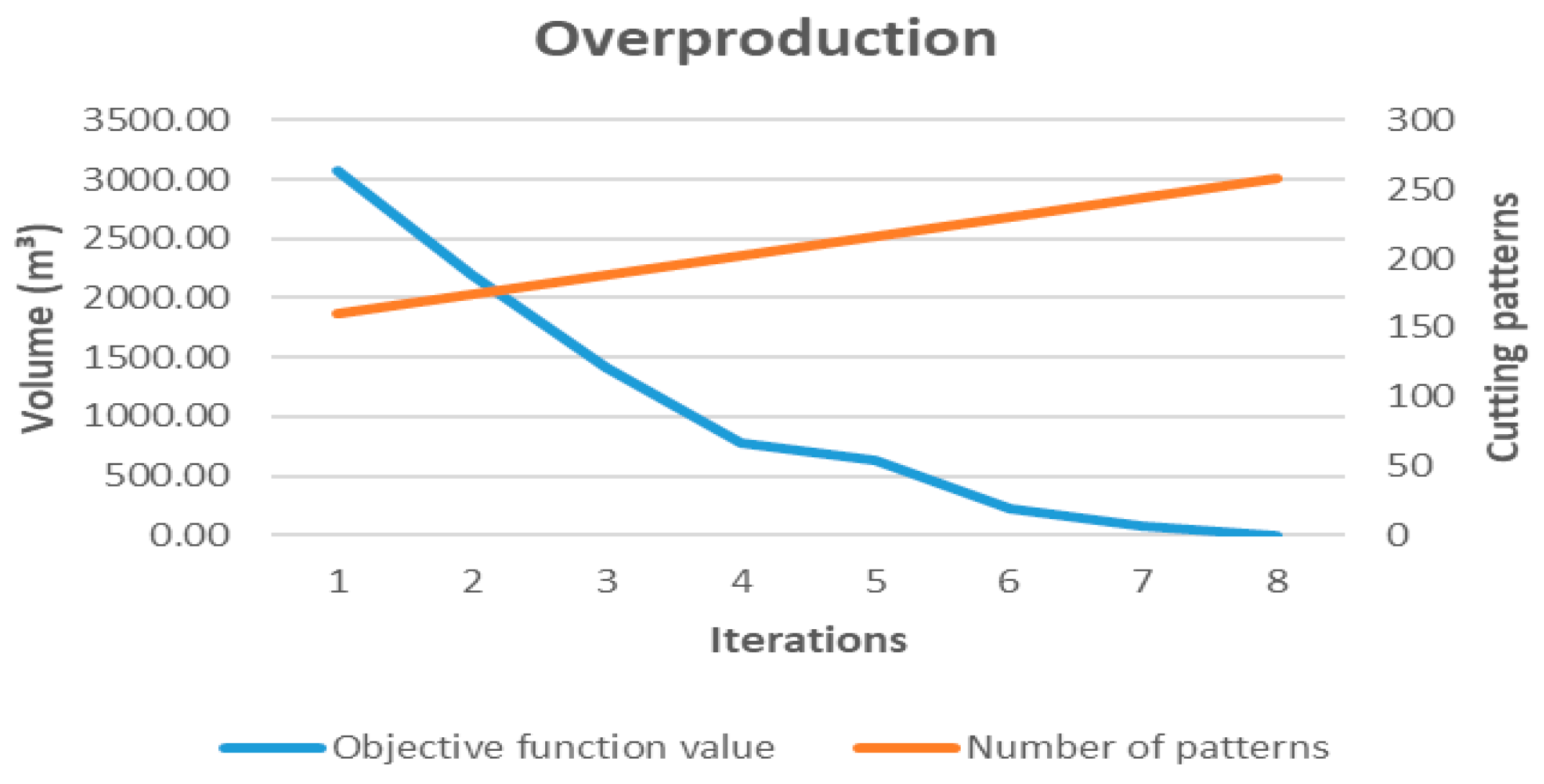

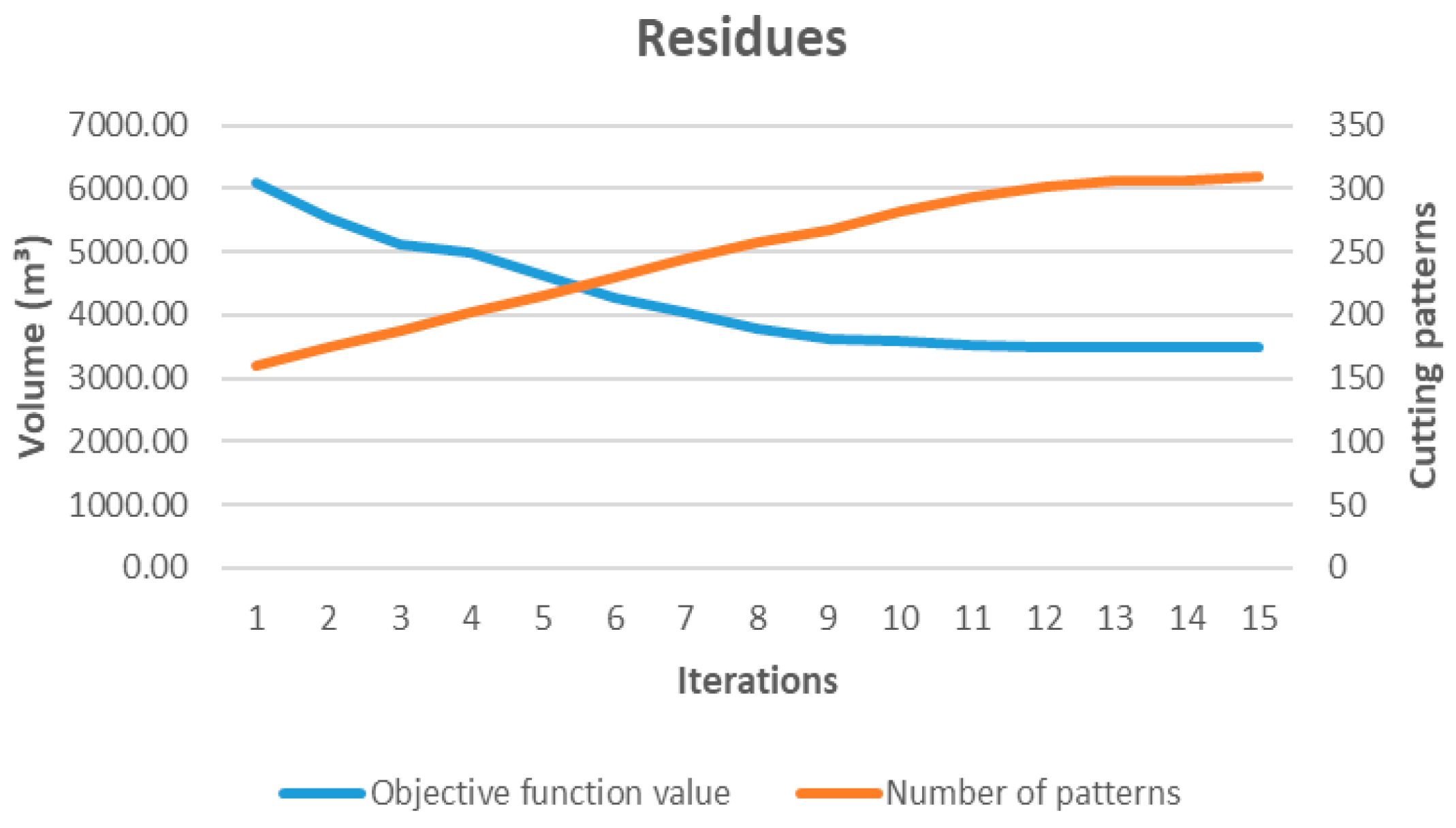

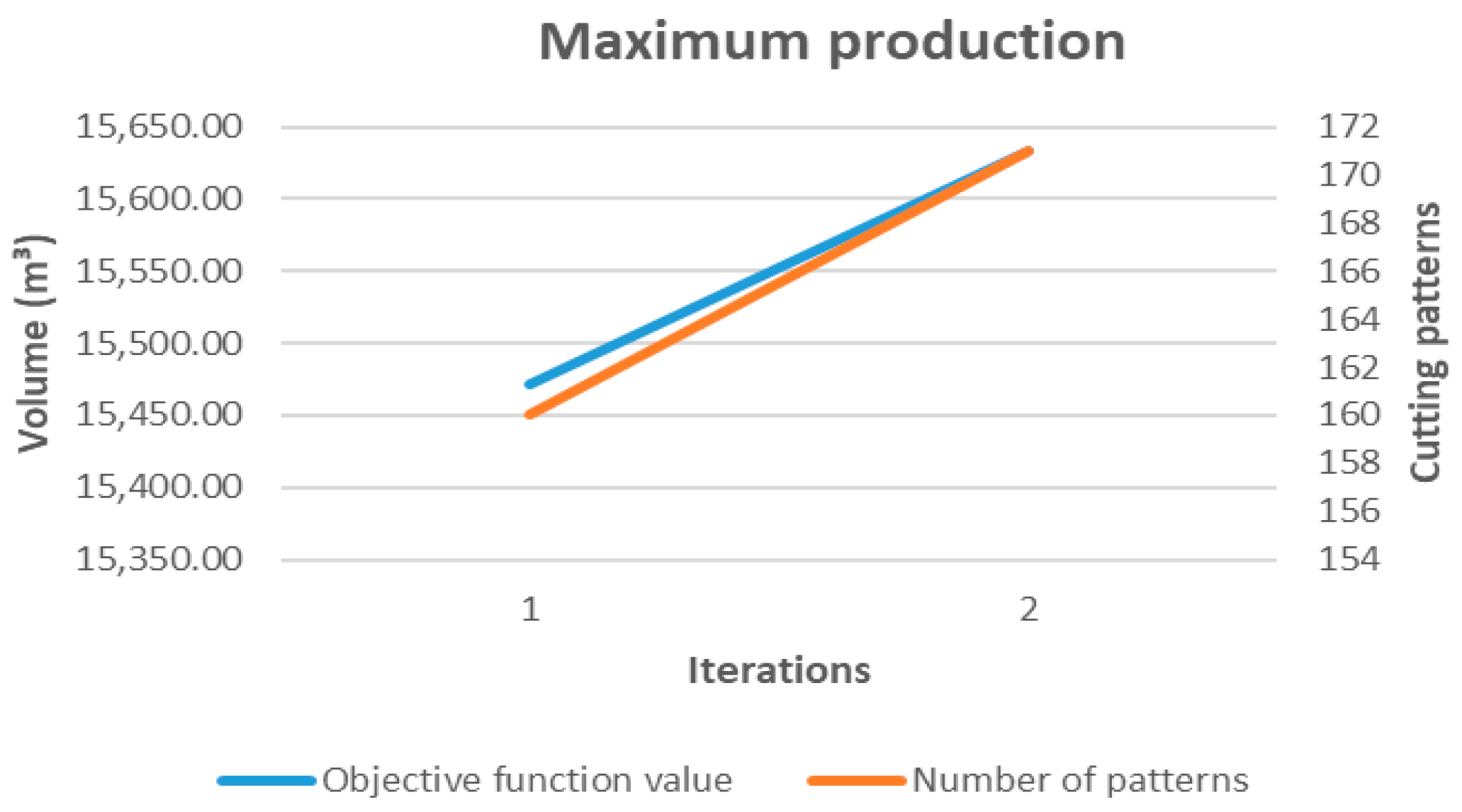

2.4.1. Experiment I: Convergence Assessment of the Column Generation Algorithm

As an initial step, a preliminary experiment was designed to observe the behavior of the proposed model throughout the iterative column generation process. This experiment makes it possible to analyze the evolution of the objective function value and the expansion of the set of log cutting patterns used in each iteration, for each of the objective functions considered.

In this evaluation, the primary model starts with a base set of 160 original patterns, which is progressively expanded by incorporating new patterns obtained from the secondary model, guided by the dual prices of the primary model. This process continues until no patterns with negative reduced cost are identified, which indicates the convergence of the relaxed solution.

For each objective function (z1 to z4), the following indicators are recorded by iteration:

2.4.2. Experiment II: Assessment of Objective Functions

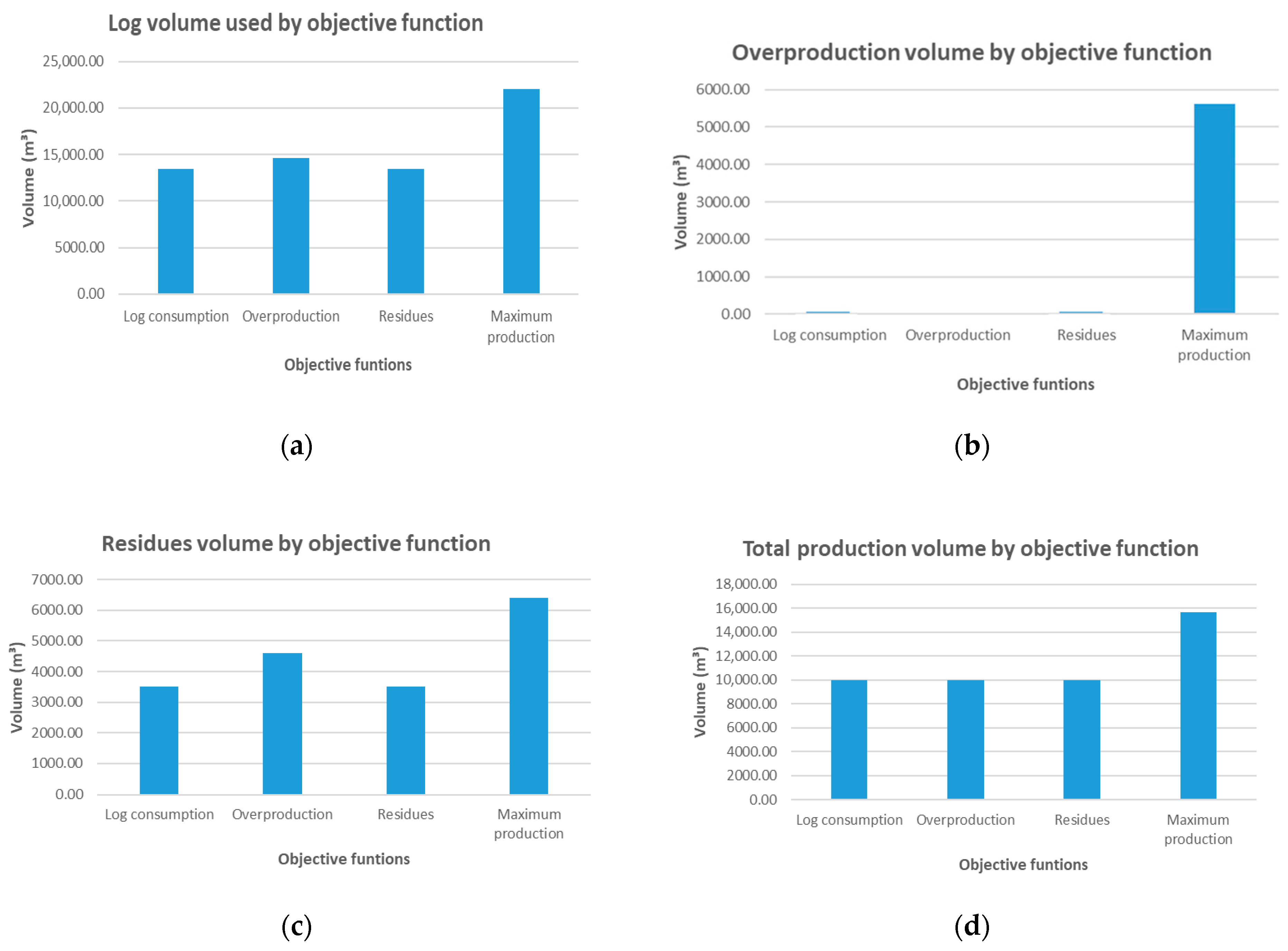

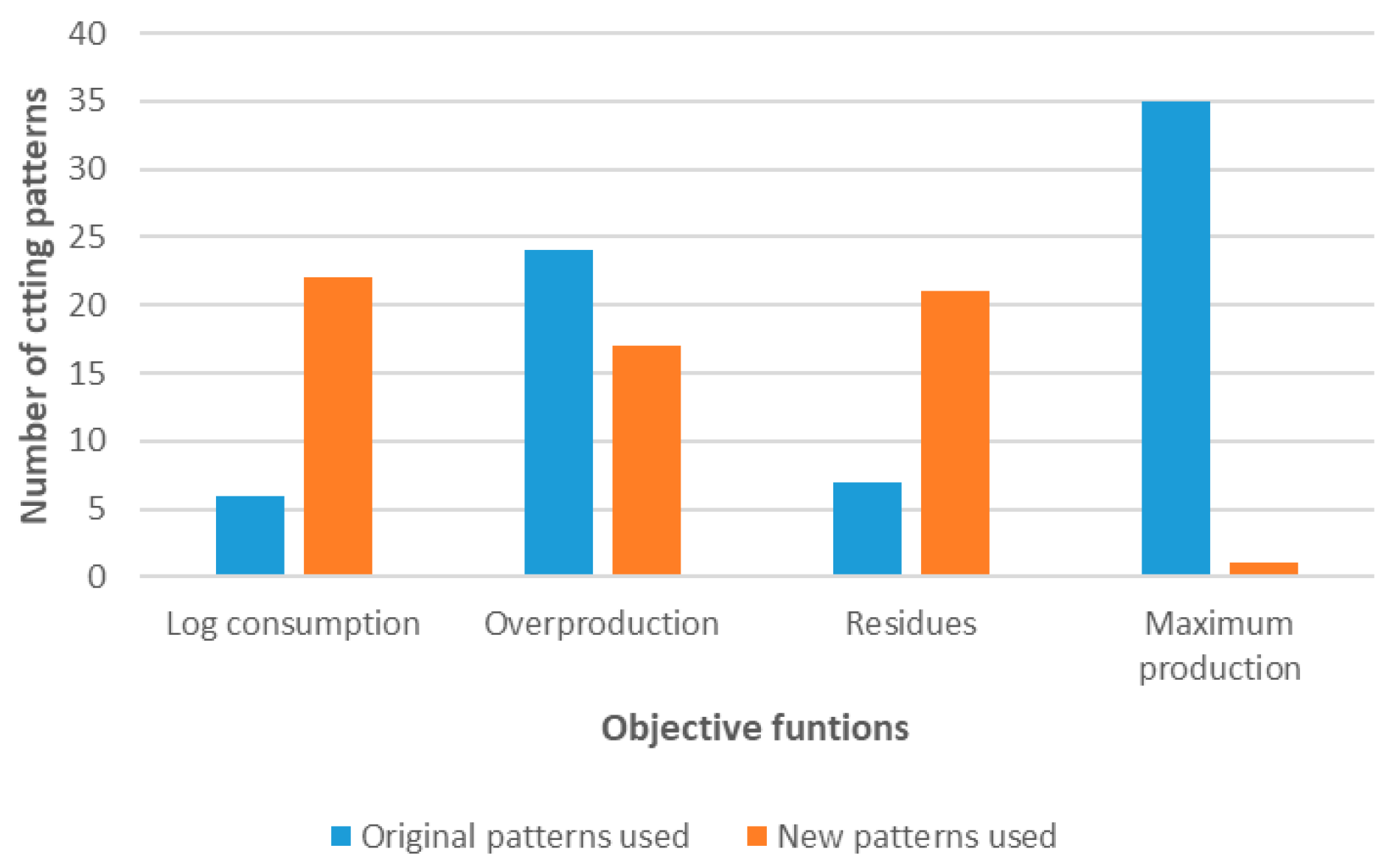

Experiment II aims to analyze how different objective functions affect the model outcomes in terms of efficiency, sustainability, and supply-demand balance. It evaluates whether the dynamic pattern generation strategy can deliver solutions superior to those offered by the base set when the model is optimized under different tactical criteria.

For this purpose, the four alternative objective functions defined for the experiments (z1 to z4) are considered, each oriented towards a key aspect of planning.

Each function is evaluated independently, using the same data instance and base set. The model is allowed to generate new patterns if they contribute to improving the solution under the criterion considered. The results are compared according to key indicators: volume of logs used, overproduction, byproducts, yield, and the number of patterns generated and utilized.

2.4.3. Experiment III: Performance Evaluation Under Restriction on the Number of Log Cutting Patterns

To simulate more realistic operating conditions, this experiment incorporates into the primary model an additional set of constraints that explicitly limit the number of distinct log cutting patterns that can be used in the solution. These constraints allow for analyzing how system performance is affected when the structural complexity of the cutting plan is controlled.

Equations (52) and (53) link the log quantity variable

with a binary activation variable

. This ensures that if a pattern is not activated

, then no logs can be assigned to that pattern (

. The value

is sufficiently large constant.

Equation (54) sets the maximum limit of distinct patterns that can be used in the solution. The parameter

is experimentally controlled and allows for restricting the diversity of active configurations, realistically simulating operational or logistical limitations of the plant.

Equation (55) defines the binary nature of the variable , which indicates whether pattern k is active in the final solution.

This group of constraints acts as a control mechanism on the solution, by conditioning the use of patterns on their explicit activation and restricting how many can be used simultaneously. Their inclusion makes it possible to evaluate how the model’s performance varies under different levels of flexibility, and to determine the balance point between efficiency, demand alignment, and operational simplicity.

The results of these experiments are presented in the following section, providing insight into the performance and adaptability of the proposed model under diverse conditions.

4. Discussion

A meaningful comparison with previous work is possible under the yield-maximization objective. Ramos-Maldonado et al. [

12] evaluate cutting patterns using a production-oriented criterion, which corresponds to our objective function z4. Under this objective, our dynamic pattern-generation approach achieves comparable or superior yield levels while additionally enabling the integration of sustainability-related tactical criteria. This expands the scope of cutting-pattern optimization beyond pure production maximization and demonstrates the added value of dynamic pattern generation for tactical planning.

4.1. Discussion of Experiment I

Experiment I show how the column generation process enables the model to iteratively adapt to different tactical objectives, progressively improving performance through the incorporation of new log cutting patterns. This structural evolution is key in tactical planning contexts for sawmills, where decisions must consider not only productive efficiency but also operational constraints and sustainability goals.

The models developed by Maness and Adams [

31] and by Maness and Norton [

32] used three-phase linear programming (LP) approaches with a variant of the Dantzig-Wolfe decomposition to optimize bucking and sawing processes in export-oriented sawmill planning. Both approaches share similar methodologies. In contrast, the primary model presented in this research is based on mixed-integer linear programming (MILP), while the secondary model employs a MIQCP to generate new cutting patterns. In comparison, refs. [

31,

32] rely on static rules without explicitly presenting their models.

The results show that for functions such as z1 (minimization of log consumption), z2 (minimization of overproduction), and z3 (minimization of residues), the base set of patterns is not sufficient to achieve sustainable solutions. A considerable expansion of the pattern space is required, reflecting the need to generate specific configurations that better balance production objectives, raw material utilization, and demand alignment. This behavior contrasts with z4 (maximization of yield), which converges rapidly using mostly pre-existing patterns, but without optimizing key aspects from an environmental perspective.

From a sustainability standpoint, the model demonstrates its ability to build solutions that reduce forest resource use, avoid overproduction, and decrease residues generation provided that sufficient configurational flexibility is allowed. This is particularly important in scenarios where responsible management, environmental impact, and efficient resource use are strategic decision factors.

Moreover, analyzing the iterative evolution provides useful tactical information: on one hand, it allows for estimating the level of computational effort required depending on the objective function; on the other, it provides planners with a tool to adjust the degree of flexibility in a controlled manner, considering the plant’s real operational capacities.

This experiment fulfills a main methodological purpose: validating that the column generation approach enables progressively more efficient and structurally adaptive solutions to be built from a base set of patterns. However, this analysis was carried out in an ideal environment, at an aggregate level without including details of daily operations.

Although the empirical validation was performed using data from Chilean softwood sawmills, the proposed model is not region or species dependent. Its formulation only requires geometric product definitions, log diameters, and supply-demand matrices, making it directly applicable to other species and industrial contexts without structural modifications.

4.2. Discussion of Experiment II

The results of Experiment II confirm that the choice of objective function has a significant impact both on system performance and on the structure of the solution generated by the model. The functions oriented toward sustainability criteria (z1, z2, z3) promoted a broader exploration of the solution space, which translated into the generation of new log cutting patterns do not present in the base set. This adaptive capacity enabled the model to construct solutions more closely aligned with tactical objectives such as reducing log consumption, minimizing overproduction, and decreasing residues.

Objective function z1, focused on minimizing total log volume, and z3, aimed at reducing waste, relied heavily on new patterns. This highlights the need for specific configurations to optimize forest resource utilization, reflecting a material-efficiency perspective consistent with sustainability principles. This behavior contrasts with z4, centered on maximizing yield, which achieved its objectives almost entirely without generating new patterns. This suggests that traditional yield-oriented patterns are adequate for production strategies focused on total output volume but not necessarily for tactical models prioritizing responsible use of raw material or environmental impact reduction.

For its part, z2 managed to eliminate overproduction without affecting demand fulfillment, though at the cost of generating more residues. This trade-off illustrates a common phenomenon in tactical decision-making: optimizing one indicator (such as overproduction) may lead to deterioration in others (such as waste). This reinforces the need to evaluate solutions across multiple indicators that integrate operational efficiency, demand fulfillment, and sustainability.

The experiment’s results demonstrate that the proposed model, by incorporating column generation and allowing for dynamic pattern creation, provides a highly valuable tool for tactical sawmill planning. Unlike approaches that operate with fixed sets of log cutting patterns, such as the model of Ramos-Maldonado et al. [

11], which focuses on maximizing volumetric yield under predefined supply and demand conditions, the present approach introduces structural flexibility that allows for dynamic responses to system variations. Similarly, the model of Parra Gálvez et al. [

10] structures pattern allocation by diameter class but does not modify the base set during the planning process. Vanzetti et al. [

22] proposes a two-module planning architecture with exhaustive pre-generation, which, while offering some adaptability, does not incorporate dynamic generation mechanisms during problem solving.

In contrast, the model proposed here aligns cutting decisions with broader operational goals, including efficient use of forest resources, reduction in residues, and demand-adjusted production. This positions it as a flexible and sustainable methodological alternative, applicable in industrial contexts where adaptability and commitment to sustainability are priorities.

The dynamic cutting modes produced by the proposed framework operate at a tactical-planning level and are intended to support, rather than replace, the real-time production scheduling systems used in industrial sawmills. In practice, the optimized set of cutting modes can serve as a refined and consistent pattern library available to planners during operational decision making, without requiring direct integration with scheduling software. This supports better alignment between tactical objectives and day-to-day decisions while preserving operational flexibility. Because the model operates at the tactical level, it does not incorporate equipment constraints or machine-capacity restrictions, which are instead addressed by operational scheduling systems used in sawmills.

4.3. Discussion of Experiment III

The results of Experiment III show how restricting the maximum number of log cutting patterns impacts model performance, not only from a technical standpoint but also from a sustainability perspective. This analysis is particularly relevant in the context of tactical planning for sawmills, where decisions must balance efficiency, industrial feasibility, and responsible resource use.

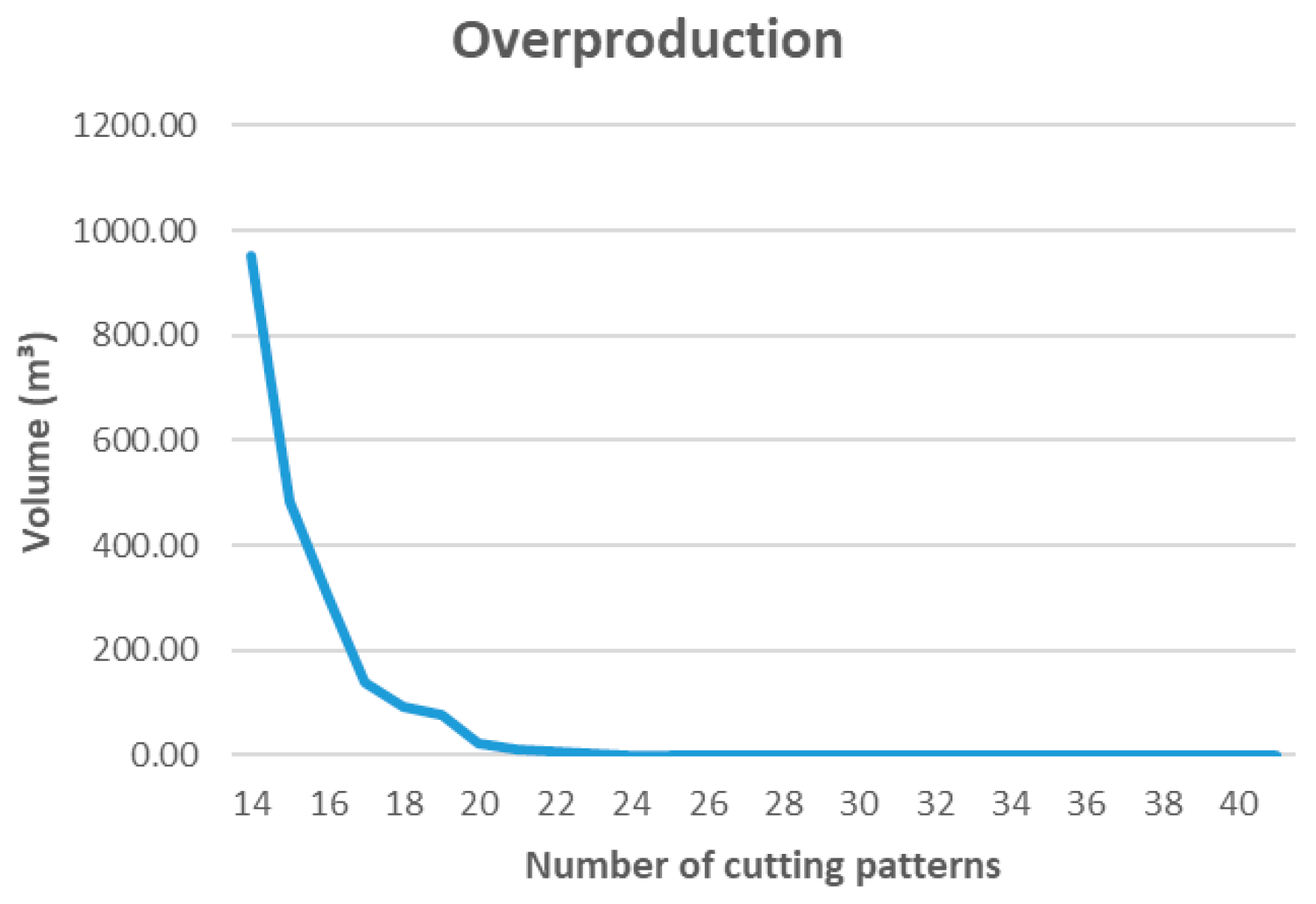

In all cases, the greatest benefits are obtained with the first increases in the number of allowed patterns, reaching a saturation point beyond which improvements are marginal. This is especially evident for overproduction minimization (z2), where the model eliminates overproduction with only 27 active patterns. This precise alignment between production and demand reduces unnecessary energy consumption, inventory costs, and the environmental impact associated with overproduction.

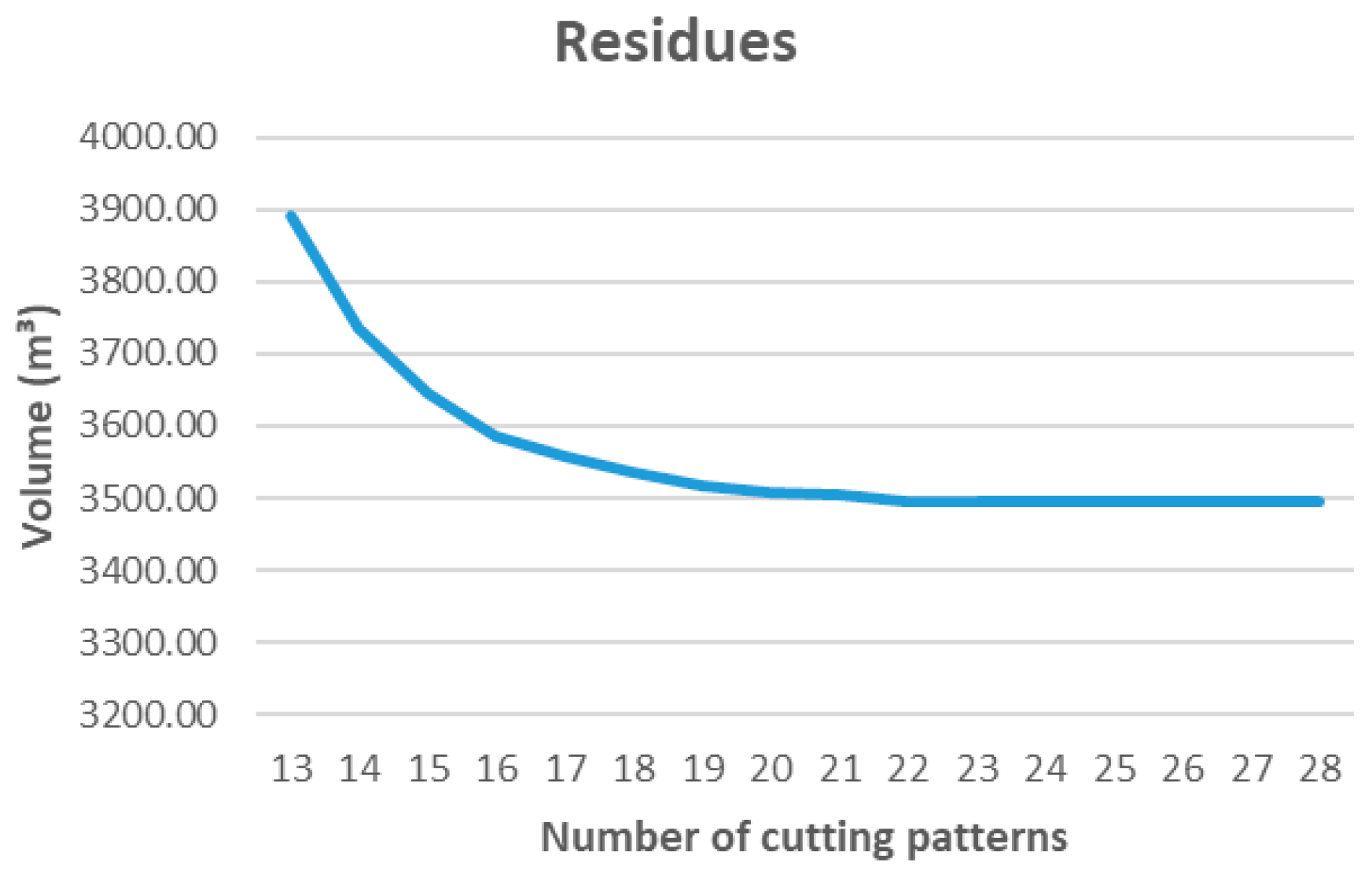

Similarly, functions z1 and z3 (minimization of log use and residues) achieve high levels of material efficiency with a moderate number of patterns. This efficient use of raw material contributes directly to process sustainability by reducing both the need for forest extraction and the generation of solid waste.

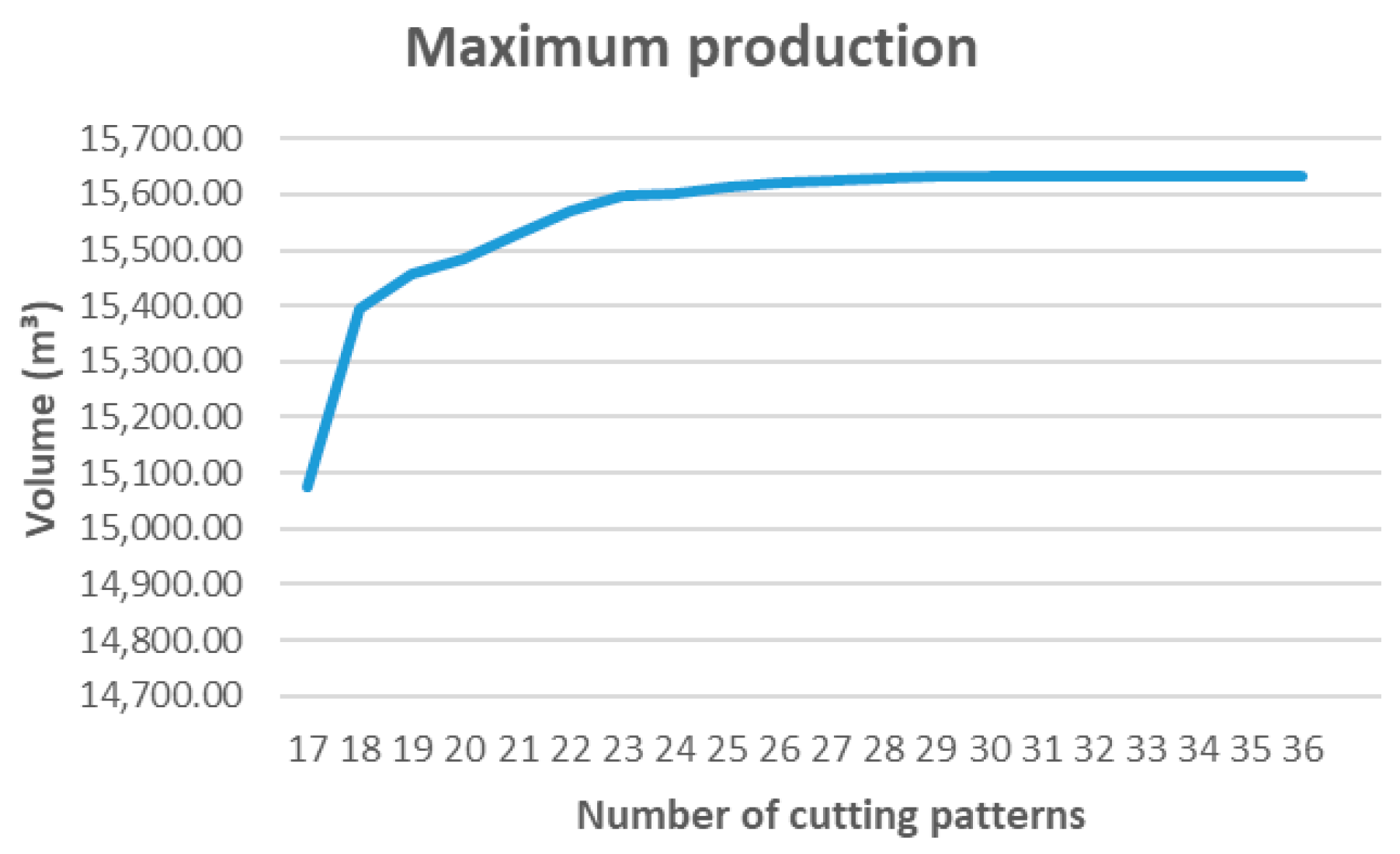

In contrast, yield maximization (z4) requires a larger number of active configurations to reach its optimal value, which may be incompatible with scenarios where operational flexibility or sustainability are priorities. Although this function maximizes the recovery of usable volume, it does not directly consider the balance between production, overproduction, and residues; therefore, its tactical application should be evaluated with caution.

The experiment validates that the proposed model not only enables the generation of efficient solutions but also provides a tool adaptable to the requirements of tactical planning in sawmills, integrating considerations of sustainability and operability. The ability to explicitly control the number of active patterns allows planners to simulate scenarios with different levels of complexity, facilitating more informed, realistic, and environmentally responsible decisions.

This behavior can be interpreted through the well-known elbow method; a heuristic widely used in clustering and optimization that helps identify the point at which marginal improvements cease to be significant as a given parameter increases. In this case, the performance plots by objective function exhibit clear breakpoints that reflect the saturation point beyond which adding more patterns yields no substantial benefits. This pattern justifies the existence of an optimal threshold of structural complexity in the solution, beyond which marginal efficiency decreases considerably [

43].

In real sawmill operations, every change in cutting pattern requires stopping the line to reset saw alignments, feeding systems, and operating parameters. This setup process typically takes between 10 and 20 min, depending on the level of automation and equipment type. Consequently, the number of active patterns shown in

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 not only represents structural flexibility but also the number of production stops required to reach the optimal solution.

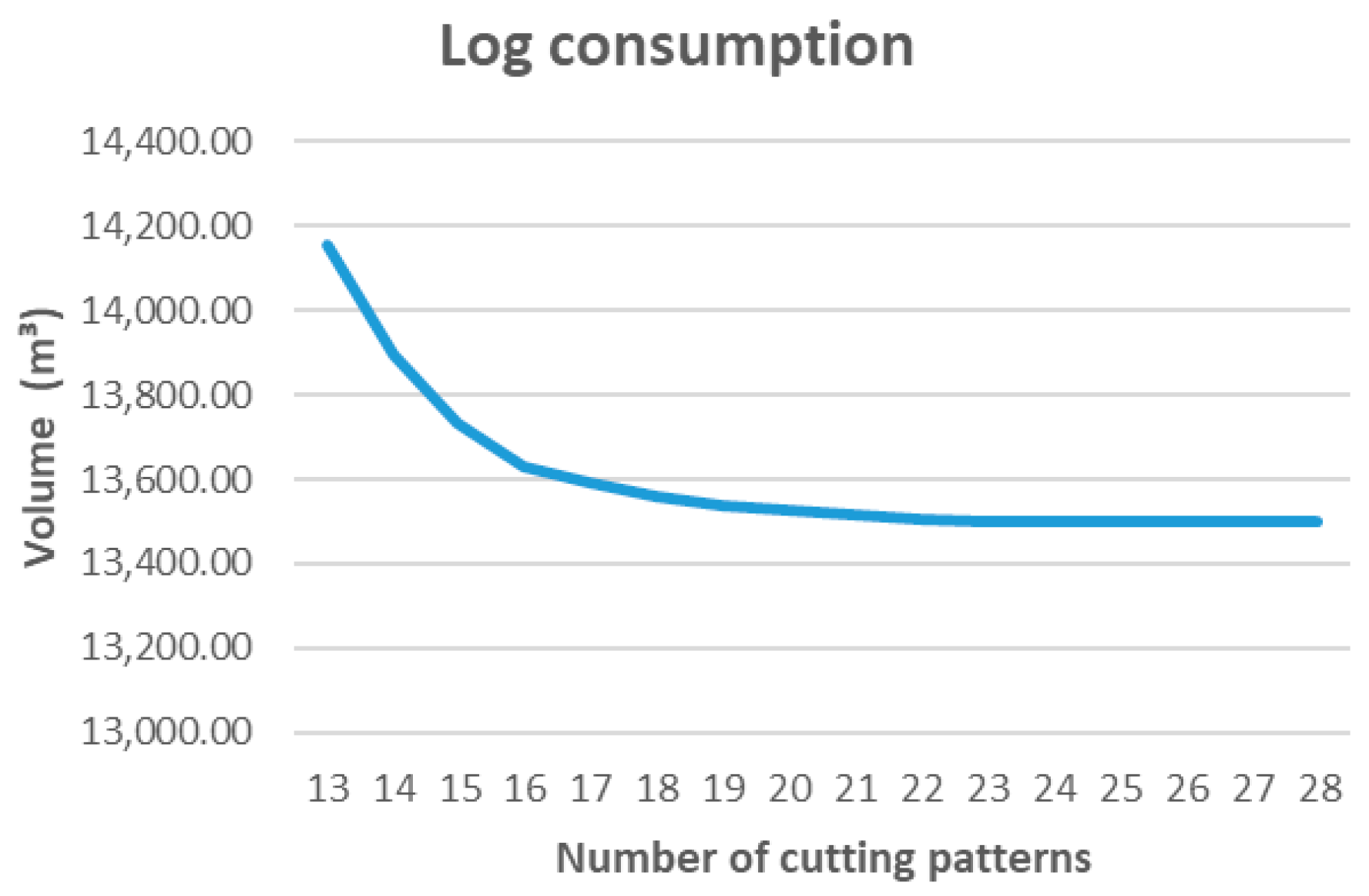

From an operational standpoint, this aspect is crucial because the results indicate that marginal efficiency gains stabilize beyond a certain number of patterns. For instance, in

Figure 13 (log volume minimization), log consumption stabilizes at around 13,500 m

3 with 23 patterns, while the global optimum at 36 patterns improves efficiency by less than 1%. Similarly, in

Figure 15 (residue minimization), waste volume ceases to decrease significantly beyond 25 patterns, with a marginal gain below 1.5% compared to the minimum achieved.

These results suggest that using more than 25–27 patterns provides negligible improvements while increasing the number of operational halts. Assuming an average setup time of 15 min per pattern change, moving from 25 to 35 patterns would result in approximately 2.5 additional hours of downtime per shift, partially offsetting the model’s efficiency gains.

Therefore, the analysis reveals the existence of a practical operating point where the marginal improvement in raw material utilization does not compensate for the additional setup time and cost. This point lies approximately between 20 and 25 active patterns, maintaining over 98% of optimal efficiency while significantly reducing machine adjustments. In this context, planners can prioritize a smaller set of representative patterns that preserve high efficiency and minimize production interruptions, achieving a quantifiable balance between performance, operational availability, and process sustainability.

It is important to note that the threshold of approximately 20–25 active patterns reflect the diminishing-returns behavior inherent to column-generation models: once the most structurally valuable patterns have been introduced, additional patterns contribute progressively smaller improvements. Although the numerical value of the threshold arises from the specific dataset used in this study, the underlying phenomenon is general and not tied to any particular region, species, or product mix. Therefore, the threshold should be interpreted as an empirical illustration of this well-known behavior rather than a universal constant.

4.4. Limitations

The model currently considers only a cant-type sawing scheme, which is the dominant and operationally representative breakdown strategy for the class of softwood sawmills addressed in this study. For these environments, restricting the model to cant sawing does not affect its practical applicability. However, mills that operate with multiple or mixed breakdown strategies would require extensions of the framework. In such cases, incorporating alternative cutting approaches, such as plain sawing, quarter sawing, curve sawing, or grade-oriented breakdown, would likely involve developing secondary models for each pattern family, as embedding several geometric configurations within a single MIQCP formulation would significantly increase computational effort. Exploring these multi-strategy extensions represents a promising direction for future research.

Moreover, the convergence and computational behavior observed in this study correspond to small- and medium-scale instances that are representative of real industrial sawmills. In these settings, the column-generation procedure performs efficiently and does not require stabilization techniques. For hypothetical very-large-scale problems, which exceed the practical size of sawmill planning, additional mechanisms, such as managing redundant intermediate columns or applying stabilization strategies, might be necessary to maintain performance. However, such large-scale scenarios fall outside the operational scope of the sawmills targeted in this work.

The model also assumes deterministic demand conditions and does not incorporate highly fluctuating or stochastic demand scenarios. Since the focus of this study is tactical planning, demand variability was kept fixed across experiments. Extending the framework to uncertainty-aware or volatility-sensitive demand environments represents a valuable direction for future research.

Finally, the model intentionally excludes real-time scheduling considerations such as equipment capacities, saw speeds, processing times, and shift calendars, since these belong to operational-level planning rather than tactical decision making. Incorporating such constraints into an integrated tactical–operational framework represents a potential avenue for future research but lies outside the intended scope of the present model.

4.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

From a theoretical standpoint, this study contributes to the optimization and cutting-stock literature by integrating column generation with an MIQCP-based pricing problem that enforces geometric feasibility. This combination allows for the dynamic creation of cutting patterns beyond predefined libraries, addressing a long-standing limitation in pattern-generation models for sawmills. The formulation presents how nonlinear geometric constraints can be embedded within a decomposition framework, thus extending the applicability of column generation to problems where pattern feasibility relies on non-separable quadratic relationships. These elements provide a methodological contribution that can be adapted to other industries with geometry-dependent cutting processes.

From a practical perspective, the results show that the proposed approach can support real sawmill planning by reducing excessive pattern inventories, minimizing unnecessary pattern changes, and enabling the construction of efficient cutting modes that better align with available log supply and product demand. Because the generated patterns are structurally feasible and interpretable, they can be incorporated into existing digital planning platforms as an updated pattern library for tactical or operational use. Furthermore, the integration of sustainability-oriented objectives, such as reductions in log consumption, residues, and overproduction, offers a pathway for sawmills aiming to adopt environmentally responsible production strategies. These insights present that dynamic pattern generation can serve as a decision-support tool that balances efficiency, operational feasibility, and sustainability in modern sawmill environments.

5. Conclusions

This study presented an optimization model based on column generation for the dynamic construction of log cutting patterns in sawmills, aimed at supporting tactical planning under different criteria. Unlike traditional approaches that use predefined patterns and focus exclusively on maximizing yield, the proposed model enables configurations adapted to different strategic objectives, integrating operational efficiency, residue reduction, and sustainability.

The experimental results showed that the model progressively improves the initial solutions by incorporating new patterns generated according to the tactical objective. This capacity for structural adaptation was key to achieving solutions with lower raw-material consumption, lower overproduction, and a smaller volume of residues, especially in functions z1, z2, and z3. In contrast, yield maximization (z4) showed that a high total production volume can be achieved, but at the cost of higher log consumption, significant overproduction, and elevated residues levels. This behavior indicates that although z4 prioritizes the recovery of usable volume, it does not optimize efficient use of raw material nor promote a balance aligned with sustainability criteria.

When the number of allowed log cutting patterns was restricted, key system indicators, such as log consumption, overproduction, losses, and total production, evolved differently depending on the objective considered. This reveals that it is not possible to improve all tactical criteria simultaneously, since optimizing one may entail deterioration in another. Thus, the model offers a flexible tool that allows the planner to select solutions according to the system’s specific priorities, balancing operational efficiency and sustainability criteria.

Beyond these results, this study provides several broader contributions. The integration of a MILP principal problem with an MIQCP pricing model within a column-generation framework shows that geometrically and dynamically generated cutting patterns can be constructed without relying on predefined industrial libraries of cutting patterns. The experiments also show that dynamic pattern generation can lead to quantitative improvements over the base set, including reductions of approximately 10–15% in log consumption under z1, elimination of overproduction under z2, and waste reductions of around 10–14% under z3. These findings position the proposed methodology as a promising decision-support tool for sawmills aiming to balance production targets with sustainability-oriented objectives.

This research also has limitations. The model assumes a cant-type sawing configuration because this is the most used in sawmills and does not yet incorporate alternative breakdown strategies. Computational performance depends on repeatedly solving an MIQCP pricing problem, which may become more demanding for very large pattern spaces or sawmills with more diverse product catalogs. Although the empirical validation used a dataset derived from Chilean softwood sawmills, the formulation itself is not region- or species-dependent, as it relies only on geometric product definitions and supply–demand matrices.

Looking ahead, several promising directions arise. Future research may extend the framework toward multi-objective optimization to more explicitly evaluate trade-offs between yield, sustainability, and demand satisfaction; incorporate uncertainty in log supply or market demand using stochastic or robust formulations; explore machine-learning-based strategies for predicting feasible geometric layouts or guiding pattern generation; and evaluate additional sawing schemes.

Overall, this study demonstrates that dynamic pattern generation enables more adaptive, sustainable, and operationally feasible decisions in tactical sawmill planning.