Abstract

In this paper, we explore the latent structures for panel data models in presence of available prior information. The latent structure in panel models allows individuals to be classified into several distinct groups, where the individuals within the same group share the same slope parameters, while the group-specific parameters are heterogeneous. To incorporate the prior information, we design a new alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) algorithm based on the pairwise group fused Lasso penalty approach. The asymptotic properties and the convergence of ADMM algorithm are well established. Simulation studies demonstrate the advantages of the proposed method over existing methods in terms of both estimation efficiency and detection accuracy. We illustrate the practical utility of the proposed procedure by analyzing the relationship between electricity consumption and GDP in China.

MSC:

62J07

1. Introduction

Panel data models are widely encountered in many substantial areas in both econometric and statistics. When conducting analyses for panel data, conventional approaches typically assume that the slopes of regressors are completely homogeneous across all individuals [1]. However, such homogeneity assumptions are not in accordance with reality through many practical analyses. See, for example, [2,3,4], to name a few. From the perspective of model strategy, the complete homogeneity assumption ignores individual-specific heterogeneity, which is quite important in panel data analysis. On the other hand, estimating parameters for each individual separately is feasible for achieving complete heterogeneity, but the estimators and relevant inferences are inefficient or even imprecise, as the time dimension T is usually very short. To strike a balance between completely homogeneous and fully heterogeneous models, a natural way is to assume that the panel units can be classified into several unknown groups, where the members within a group share the same slope parameters, while the slopes across different groups are different. In this way, the convergence rate of estimators changes from to , where is the total number of individuals in the kth group. The group structure here is called latent structure [5], and the identification of latent structures is sometimes called homogeneity structure learning [6,7] or subgroup identification [8].

1.1. Literature Review

The existing literature on exploring the latent group structure can be roughly classified into three categories based on different perspectives. First, researchers have found that identifying the latent group can be formulated into a penalization estimation context, such that modern feature selection techniques [9,10] can be employed. A pivotal contribution in this area can be traced back to [5], who developed a novel variant of the Lasso estimator called Classifier-Lasso (C-Lasso). The penalty form of C-Lasso takes an additive-multiplicative form, which forces the parameters of individuals into several groups for a given number of groups. This method had subsequently been extended in various panel models, such as [11,12,13,14]. Recently, ref. [15] proposed a new penalized estimation procedure based on the pairwise adaptive group fused Lasso (PAGFL) penalty, which can automatically identify latent group structures by shrinking the difference in slopes between two individuals towards zero. Compared to C-Lasso, this approach is guaranteed to converge to a unique global minimizer. Second, note that clustering panel individuals into groups is essentially a supervised clustering problem. Hence, the classical K-means algorithm can be adapted to the panel regression framework with group structures with slight modifications. Research in this direction includes [2,16,17]. The third popular approach is based on the sequential binary segmentation algorithm (SBSA) of [18] which was originally designed for structural break detection. Ref. [19] employed the SBSA to detect latent group structures in nonlinear panel models, which consists of two steps: first, sorting the preliminary unconstrained consistent estimators of the regression coefficients, and then performing break point detection. The individuals within adjacent estimated change points therefore form a group. This idea has subsequently been extended by [20,21] to detect the latent structures in spatial dynamic panels and time-varying panels.

These methods make important contributions but often ignore the use of prior information. It is well-known that incorporating prior information in economic and statistical modeling can help improve estimation performance. For example, in the application of predicting clinical measures from neuroimages, ref. [22] proposed a sparse fused group Lasso method that incorporates spatial and group structure information to enhance prediction accuracy. Similarly, ref. [23] detected the sparsity and homogeneity of regression coefficients with imposed prior constraints. To quickly identify clustered patterns in spatial regression and reduce computational burden, ref. [24] built a minimum spanning tree (MST) based on the spatial neighborhood information, and then detected homogeneity in coefficients based on the tree. Along this line, ref. [25] proposed a new MST by leveraging the concept of network topology and the local model similarity, simultaneously. Numerical experiments and real-world data analysis in the literature demonstrated that incorporating more prior information can achieve better estimation and clustering efficiency.

In panel data analysis, researchers often have access to prior information before economic modeling, such as existing research conclusions or objective geographic information. For example, ref. [15] used the preliminary individual-specific estimator to construct the data-adaptive weights in PAGFL. The adaptive weights can be regarded as the indicator for similarity among units that implies the likelihood of two units being in the same group. One important example, which is closely related to this work, is [26], who extended the idea of [6] and exploited a panel-CARDS algorithm. This method first sorts all individuals based on a preliminary estimator, and then constructs an ordered partition set for the individuals. By applying shrinkage estimation between and within the segments, the latent structure can be identified in a data-driven manner. Notably, constructing the rank mapping from the preliminary estimates effectively borrows prior information. Another leading example arises from [2], who studied grouped fixed effects and assumed that some coefficients do not change across individuals. This model setup also posits the prior information that the coefficients of certain regressors are homogeneous across individuals. Hence, as noted by [2] in their supplementary material, adding prior information on the structure of unobserved homogeneity deserves further investigation, and we are currently working on this issue.

1.2. Contributions and Organization

This paper mainly focuses on incorporating the prior information to improve the latent structures detection performance. The contributions are as follows. First, we provide a general prior information framework that can be represented as a constrained region for regression coefficients for panel models. To identify the latent group structure and utilize the prior information, we develop a novel penalized estimation scheme based on the concave pairwise fusion penalty combining the constraint information. Second, due to the restrictions imposed by the prior constraint, traditional numerical optimization algorithms cannot be directly applied here. To implement the proposed approach, we further design an alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) algorithm [27] for solving the constrained fused Lasso problem. The ADMM algorithm is straightforward and easy to implement using free software such as R. Additionally, we have developed a new R package phpadmm to facilitate the estimation procedures described in this paper, which is available upon request. Third, we also demonstrate the convergence property of the ADMM algorithm and the asymptotic results for the estimators. We validate the theoretical results through simulation studies and real-world application. Fourth, we apply the proposed latent structures detection procedure to investigate the relationship between electricity consumption and GDP in China, a significant topic that has garnered considerable interest in the field of energy economics, and find four subgroups among the 30 provinces.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We illustrate the proposed ADMM estimation method in Section 2. The convergence of the algorithm and the asymptotic theory for the estimators are examined in Section 3. Section 4 compares the finite sample performance of different methods. We investigate the effect of electricity consumption on GDP using proposed methodology in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper. The proofs and additional testing procedure are given in the Appendix.

Notation. Throughout this paper, we adopt the following notations. Denote as a zero vector, as a unit vector, and as a identity matrix. Let be the inner product of two vector and with the same dimension. For an matrix , we denote its transpose as and . Throughout this paper, a superscript zero on any quantity refers to the corresponding true quantity, which is a fixed number, vector or matrix.

2. Model and Proposed Estimation Method

2.1. Panel Heterogeneity with Prior Constraint Information

Let be the real-valued dependent variable and a vector of regressors for and , where i and t index the individual and time respectively. We consider the following linear panel model with grouped latent structures pattern:

where is the fixed individual effect for the ith individual, is error term with mean zero, and is a vector of unknown coefficients for the ith individual. The set of coefficients admits the following latent grouping structure

where is an unknown integer, for any , and represents the common slope parameters for the kth subgroup. The set forms a partition of and for any .

Let be a coefficient matrix, and let . In this paper, we assume that the prior information can be formulated as a constrained region, i.e.,

where is a non-empty convex set, which is quite general. For example, in a cross-province panel data analysis, one may consider that the provinces in neighboring regions are more likely to belong to the same group. We can incorporate geographical information into . Similarly, in financial studies, the financial returns of similar industry sectors tend to share the same scores on the common factors. In addition, when , group identification in (2) simplifies to the no-prior information situation, which has been discussed by e.g., [5,12,13]. The convex set is user-specified that can include equality constraints, inequality constraints, or other constrained forms depending on practical considerations. To enhance the readability of this paper, we summarize the key notations in Table 1.

Table 1.

The notations in our working model.

Prior information is typically known and significant, especially in the context of this paper. As mentioned earlier, several existing methods has utilized the prior information in identifying the latent group structures in panel models, including the ordering-based method [26], and the adaptive weights in the group fused Lasso penalty [15]. In essence, these two methods both make use of the distance between any two units’ initial slope estimators. In contrast, our method generalizes the definition of prior information including both the equality and inequality constraints. We summarize the differences between the existing works and our framework about prior information in Table 2. Effectively utilizing this prior information can enhance both homogeneity detection and parameter estimation accuracy. Our objective in this paper is to explore how to incorporate these prior constraints (3) into the process of detecting homogeneity.

Table 2.

Comparison with other literature in latent structures identification for panel models.

2.2. A Regularized Approach

To detect homogeneity in panel data models, one may utilize the K-means clustering method, as demonstrated by [2,8], or the binary segmentation method proposed by [28]. However both methods struggle to incorporate prior information effectively. In this paper, we consider a regularized approach with a concave pairwise fusion penalty to detect homogeneity in model (1). This method was firstly applied in [29] for subgroup analysis and has been extensively employed in various fields, such as precision medicine. After concentrating out the fixed effects, the objective function can be represented as

where and in which and , is penalty functions and is a tuning parameters that control the degree of penalty on . There are a total of terms in , which encourages shrinkages of the pairwise differences in slopes for any two subjects. This regularized adjustment can identify the latent homogeneous structures for the coefficients . Ref. [30] pointed out that the non-convex penalties should satisfy four conditions, and the smoothly clipped absolute deviation (SCAD) [9] and minimax concave (MCP) [31] penalties are adequate choices.

To further incorporate the prior constraint condition (3), we introduce a new regularized term and rewrite the objective function (4) as

where is an indicator function for , equaling a constant when belongs to and otherwise. It should be noted that directly minimizing the Equation (5) is computationally challenging, since the SCAD and MCP penalties are not convex, and the pairwise fusion penalization term is non-separable concerning in the estimation. To achieve computational feasibility, we formally propose an ADMM algorithm to minimize (5).

2.3. ADMM Implementation

ADMM algorithm is an optimization algorithm that is particularly useful for solving optimization problems with specific structures, such as those involving separable or block-separable objective functions [27]. The key idea of the ADMM algorithm is to decompose a global optimization problem that is hard to solve into several small pieces that can be solved more easily. In terms of our optimization problem, following the principle of ADMM, we first introduce two sets of auxiliary parameters and to reparameterize the objective function (5) as a constrained optimization problem

where and . To solve (6), we use the ADMM algorithm to solve the following augmented Lagrangian function

where , are Lagrange multipliers, and , are two fixed augmented parameters. The ADMM algorithm has the advantage of decomposing (7) into several manageable subsets. Along this line, we consider alternating minimization for each block of parameters and . Specifically, given the current values at the mth iteration, denoted as , the ADMM computation at the th iteration proceeds as follows:

For the first minimization problem in (8), is the minimizer of

By simple algebraic manipulation, we can rewrite it in matrix form

where is a vector with , is a matrix with , and is a matrix, where ⊗ represents the Kronecker product, and is the vector with one at the ith component, and zeros elsewhere. Notably, the minimizer has a closed-form solution:

For in (9), it is actually a standard convex optimization problem, since we only need to minimize

where . In practical implementation, we employ the quadratic programming algorithm by the R function “solve.QP” available from the package quadprog.

For in (10), by discarding the terms that are independent of , we just need to minimize

where . For the MCP with , the updated has a closed-form solution

For the SCAD penalty with , the update is given by

where is the groupwise soft-thresholding operator with if and 0 otherwise.

As suggested by [27], a reasonable termination criterion for an ADMM algorithm is that both the primal and dual residuals are sufficiently small. In this paper, the primal and dual residuals are defined as

and

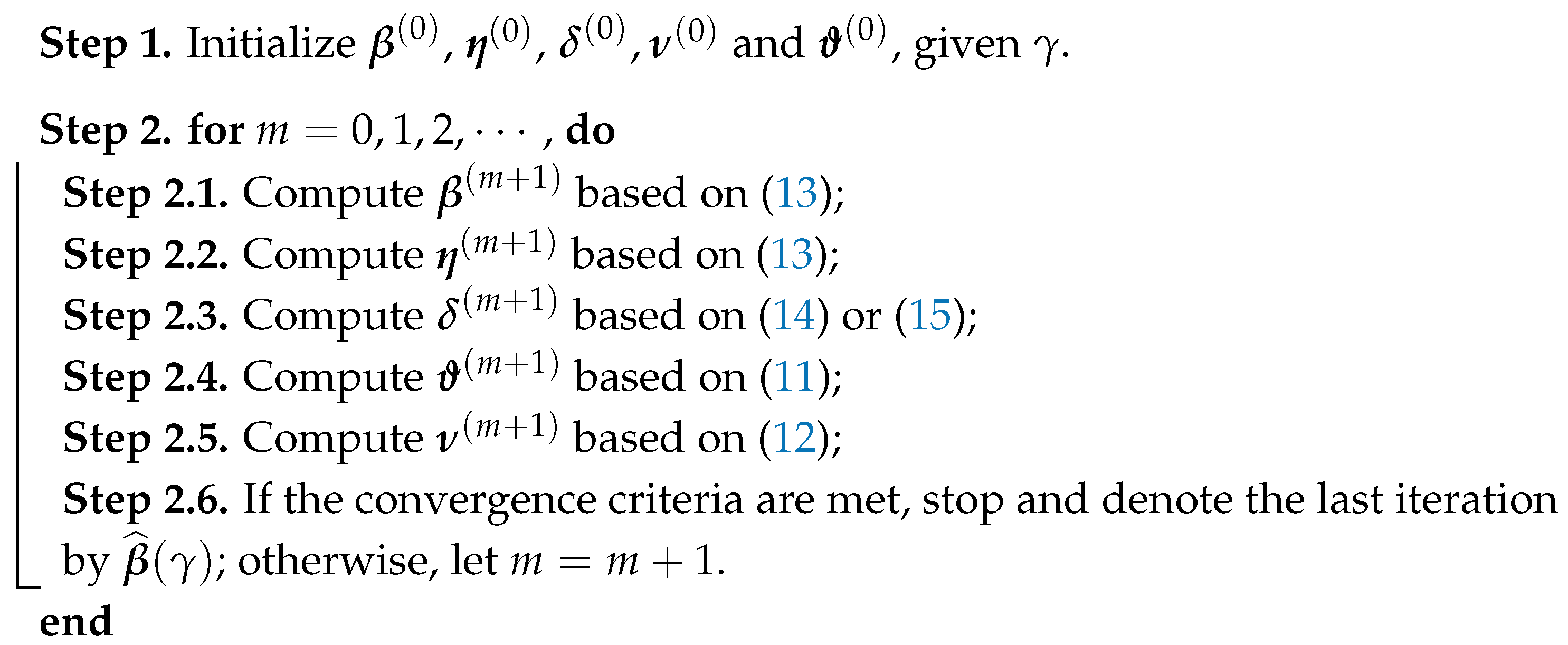

respectively. When for and hold, where and are pre-specified feasible primal and dual tolerances, we stop the iteration. We summarize the above procedures in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: ADMM algorithm for panel data models with prior constraints |

|

2.4. Initial Values and Tuning Parameter

In nonconvex optimization, selecting an appropriate initialization for parameters is crucial, because this will not only produce an optimal solution but also significantly accelerate the iterations. As proposed by [26], we set the initial values for as the estimators without the latent group structure, that is

Solve the optimization problem yields the least square estimates

for . Then, set , , , and . The question arises regarding how to determine the tuning parameters , and . Following [29], we set and .

The selection of is particularly important, since the performance of group structures identification depends on . Following the strategy of [5], we minimize the following BIC-type criterion function:

where is the sum of squared residuals, and denotes the number of groups corresponding to . Here, the positive constant that depends on N and T serve as a balance between the degrees of freedom and the model fitting errors. To select the optimal , define a grid of points with equal spacing. To speed up the computation, we employ the warm start strategy. Specifically, for each , we compute the solution path under the initial value . The optimal value for is defined as .

3. Theoretical Analysis

In this section, we mainly discuss the the convergence of the ADMM Algorithm 1, and establish the asymptotic property of the proposed estimator.

3.1. Convergence of the Algorithm

Under some mild conditions, the convergence of the ADMM algorithm can be guaranteed. For the iterated sequence , there exists a global minimizer satisfying the first order condition for a stationary point The following proposition illustrates the convergence of Algorithm 1.

Proposition 1.

Proposition 1 indicates that Algorithm 1 converges if both the primal feasibility and dual feasibility hold. The proof of this proposition follows a strategy similar to that in [29], and the detailed proof is postponed to the Appendix.

3.2. Asymptotic Property

We now establish the theoretical properties of the penalized estimator. First, we introduce some notations. Let and . Let be an arbitrary K-partition of . We define

where . Denote as the number of elements in the kth group. Define as the scale penalty function and as its first-order derivative. We then introduce the following assumptions.

Assumption 1.

(i) is stationary strong mixing for each i with mixing coefficients . satisfies for some constant and . (ii) The random variables are independent, and for some constant and . (iii) There exists two positive constants and such that and . (iv) The error term satisfies , and . (v) either tends to infinity or remains fixed as and .

Assumption 2.

(i) The function is symmetric, non-decreasing and concave on . It satisfies and is constant for all for some constant . (ii) The derivative satisfies and is continuous except for a finite number of values of t.

Assumption 3.

(i) There exist positive definite matrices for such that as or . (ii) Let . Then as or where equals if is not exogenous and 0 otherwise.

Assumption 4.

as where

Assumption 5.

As (, and .

Assumption 1(i,ii) imposes some conditions on , which are quite common in panel data models. Assumption 1(iii,iv) specifies moment conditions on the regressors and the noise term , respectively. Assumption 1(v) allows the number of elements in each group to be finite, which distinguishes it from the conditions set forth in [5]. Assumption 2 is standard for concave penalty functions, such as SCAD and MCP. Assumption 4 is utilized to study the asymptotic normality of the proposed estimators. Finally, Assumptions 4 and 5 are adapted from [5] to demonstrate the classification consistency described in (18).

Once is given, the estimated group pattern can be directly derived by classifying the coefficients ’s into groups. We denote as the estimated number of groups and as the common slope shared by the kth group for . By definition, the estimated group pattern is given by

We then have the following limiting distribution for .

Theorem 1.

Suppose that Assumption 1–3 hold. Then,

for as or .

Theorem 1 demonstrates that the group-specific estimator possesses the asymptotic normality properties with a convergence rate of . If the group membership is known, the oracle estimator for is given by

As pointed by [5,26], and share similar asymptotic normality. Given the estimated grouping structure , a post-Lasso version of is obtained by

The post-Lasso estimators perform at least as well as the Lasso estimators in terms of convergence rate, but they exhibit a smaller second-order bias, as shown by [32]. It would be interesting to investigate the higher-order asymptotic properties of the post-Lasso estimators within our framework.

We utilize the information criterion defined in (18) to determine the number of groups. The following theorem justifies its asymptotic validity.

Theorem 2.

Suppose that Assumptions A1–A2 and A4–A5 hold. The information criterion in (18) will select a optimal tuning parameter such that the estimated approaches to the oracle estimator with probability approaching 1, and

Theorem 2 indicates that under some mild condition, the minimizer of (18) can only be the one that produces the correct number of groups, as N or T or both go to infinity. Since in the IC (18) plays a crucial role in determining the latent group structures, we follow [5] to pick by trying a list of candidates. Similar to [26], we find that has fairly good sample performance. The same setting is also aplied in the empirical study.

4. Simulation Studies

In this section, we conduct a series of simulation studies to assess the finite sample performance of the proposed method. We consider the following three data generating processes:

4.1. Basic Setup

DGP 1. The first data setting is similar to the GDP 1 in [5]. Here, the observations are generated from a linear panel model where with the fixed effect following an i.i.d. standard normal distribution across time. The error terms and are i.i.d. standard normal and independent of . The slopes of individuals are divided into three groups with a ratio of . The true coefficients are

DGP 2. The DGP 2 is similar to the DGP 3 in [26]. In this setting, the coefficients are divided into eight groups, where the first group accounts for 30% of the total individuals and each of the remaining seven groups shares 10% of individuals. The generation for is similar to DGP 1. The group-specific coefficients take the values

DGP 3. In the third DGP, we let and for . Individuals are also divided into three groups with a ratio of . The true parameter values for each group are

The constraint set for each DGP includes both equality or inequality constraints, which are described as follows.

- (i)

- (equality constraint:) For , the sum of coefficients for each individual is the same. For , the sum of all elements equals zero, and for , the coefficients for the first regressor remain constant across all individuals.

- (ii)

- (inequality constraint:) For , all elements in the coefficient matrix are required to be greater than zero.

Hence, the constrained regions for is

where and . For ,

where . For ,

where .

Throughout these DGPs, we consider the individual sizes and the time spans and 40. The error terms are drawn from a standard normal distribution, independent across i and t, and are also independent of all regressors. The fixed effects and the error terms are mutually independent. For each case, we conduct 300 replications. For comparison, we also consider the results obtained without prior information as reported by [5].

4.2. Simulation Results

We present the frequency with which a specific number of groups is obtained across 300 replications for all DGPs. While the accurate determination of the number of groups is undoubtedly crucial, this metric alone does not provide insight into the degree of similarity between the estimated groups and the true groups. Following [6], we employ the normalized mutual information (NMI) measure to assess the similarity between the estimated group structure and the true group structure . Specifically, for two sets of disjoint clusters and on the same set , the NMI is defined as

where

where denotes the cardinality of set A. Obviously when two groupings are exactly the same, i.e., , we have , and . In general, the NMI measure takes values on , and larger NMI implies the two group structures are closer. To measure the estimation accuracy for slope parameters, we use the average model error, which is defined as .

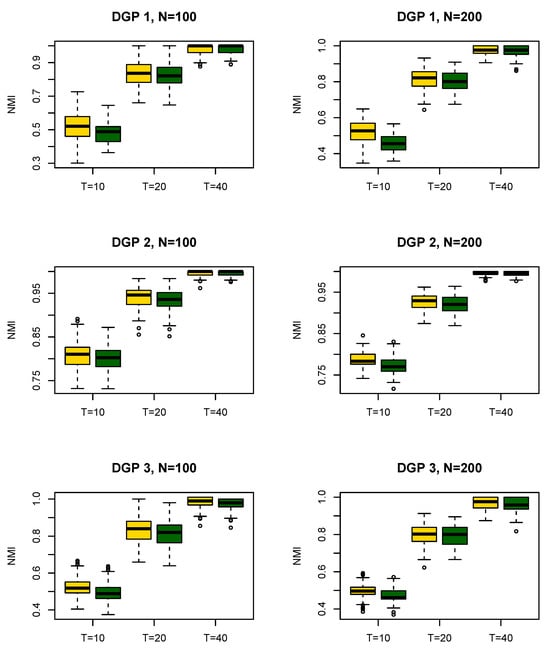

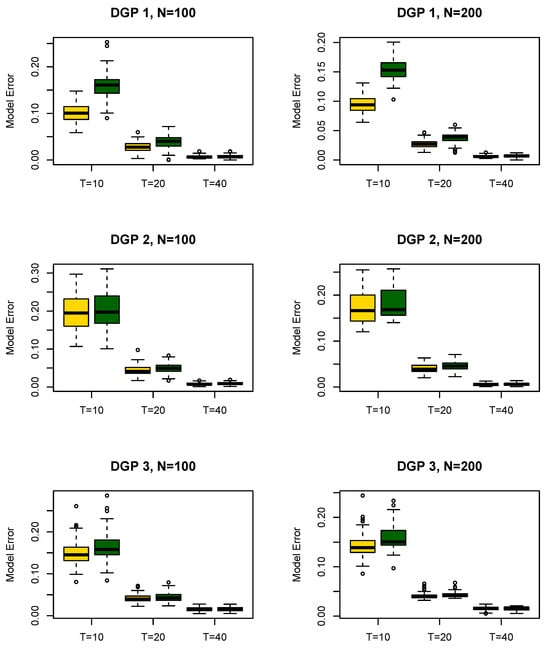

Figure 1 reports the classification results across DGPs 1–3 for difference combinations of N and T. The yellow and green boxes represent the detection results with and without prior constraints, respectively. It shows the NMI between the estimated group structure and the true group structure , and suggests that, as N or T increase, the NMI increases rapidly for both methods. More importantly, our method exhibits higher NMI values across all DGPs, which implies that incorporating prior information can substantially improve the classification performance. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced when T is small. We display the average model estimation error in Figure 2. As expected, the average model estimation error decreases as N or T increase. It is obvious that the proposed parameter estimators has smaller estimation biases, since some prior constraint information can help us to gain the extra efficiency of homogeneity detection.

Figure 1.

The normalized mutual information across different N and T for DGPs 1–3.

Figure 2.

The average model estimation errors across different N and T for DGPs 1–3.

Next, give the number of groups, we focus on the point estimation of the post-Lasso estimator. To save space, we report only the simulation results of the first group-specific parameter of all DGPs in Table 3, based on individuals. The oracle estimators, which assume that the latent group is known, are also included for comparison. As shown in the Table, the biases of the three types of estimators become negligible as T increases, indicating that all the estimators are consistent. Additionally, the standard deviations (SD) are close to their corresponding estimated standard errors (ESE), and the empirical coverage probabilities (ECP) converge to the nominal level of 95%. This validates the asymptotic normality properties of the proposed estimator, as demonstrated in Theorem 1. The no-prior estimators yield relatively smaller ECP and larger biases compared to the other two types of estimators, especially when T is small. Undoubtedly, the oracle estimators perform reasonably well, and our method produce results closer to those of the oracle estimators. In summary, incorporating prior information significantly improves the finite sample performance in terms of estimation efficiency, particularly when the time span is small.

Table 3.

The parameter estimation results of for DGPs 1-3 based on .

5. Empirical Analysis

With the deepening of China’s reform and opening up, the country has undergone profound changes over the past few decades, becoming the second-largest economic entity and the second-largest power consumer in the world. It is well known that electricity plays a crucial role in both human activity and industrial production, including sectors such as communication and engineering. Thus, electricity serves as a solid foundation for economic development. Consequently, many researchers have focused on the relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth. For example, ref. [33] found that real GDP and electricity consumption in China are cointegrated using data from 1971 to 2004. Additionally, ref. [34] investigated the relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth through a panel data analysis. China’s vast territory encompasses 34 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, creating a significant domestic market. This paper primarily focuses on the homogeneous effect of electricity consumption on GDP across these provinces.

GDP is the most closely monitored statistical index in macroeconomics and serves as an important measure of economic development. At the beginning of each year, the Chinese government releases the provincial GDP data for the previous year. The electricity consumption data used in this study are derived from the Li Keqiang Index (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Keqiang_index#) (accessed on 1 February 2025), which has been cited by The Economist as a reliable measure of China’s economy. This index incorporates three indicators electricity consumption, railway cargo volume, and bank lending that reflect the operation of China’s economy more accurately. Due to significant data gaps and challenges in data collection, the Tibet Autonomous Region, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan are excluded from this analysis. Therefore, the study includes a total of 30 provinces, with observations spanning from 2001 to 2019, resulting in and . All data utilized in this study are sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook Database, available at https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj (accessed on 1 February 2025).

We first examine the existence of a homogeneous effect across provinces using a residual-based bootstrapping procedure. The detailed algorithm can be found in the Appendix. The resulting p-value is very close to zero, indicating the statistical significance of the homogeneous effect. Moreover, numerous empirical analyses suggest a positive relationship between GDP and electricity consumption. Therefore, we assume that the coefficients for all provinces are positive as prior information. To investigate this hidden homogeneity, we consider the following linear fixed effects model with a latent group structure:

where is the logarithm of GDP for the ith province at the tth year, represents electricity consumption, characterizes the fixed effect, and is the error term. The prior information here includes a inequality constraint for parameters ’s, i.e., .

Table 4 presents the classification results using two different approaches: the proposed estimator incorporating the inequality constraint and the PGFAL estimator proposed by [15] that does not account for the prior constraint. Using our proposed ADMM algorithm described in Algorithm 1, the provinces are divided into two groups. As shown by the Table, Group 1 includes provinces such as Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Shandong, Shanxi, Shanghai, Sichuan, Xinjiang, Yunnan, and Zhejiang, with an estimated coefficient of 1.1692. Group 2 comprises Beijing, Gansu, Guizhou, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Jiangxi, Ningxia, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Tianjin, and Chongqing, with a significantly higher coefficient of 3.4770.

Table 4.

Classification results among 30 provinces in China.

Group 1 consists largely of provinces from the Eastern and Central regions, characterized by advanced industrialization, technological innovation, and a strong emphasis on services and capital investment. In these regions, the direct relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth is weaker, as economic growth is increasingly driven by non-energy-intensive sectors. While electricity consumption remains significant, its marginal impact on GDP growth is reduced due to energy efficiency improvements and shifts toward high-value-added industries. Group 2, primarily consisting of provinces from the Western and Northeastern regions, shows a stronger dependency of economic growth on electricity consumption. These regions are still in the process of industrialization, infrastructure development, and urbanization, making electricity consumption a crucial driver of economic growth. Beijing, Tianjin, and Chongqing are notable inclusions in Group 2 despite being considered economically advanced. This classification can be explained by the ongoing infrastructure expansion and high-tech investments in these cities, which require substantial energy inputs. Beijing and Tianjin, while economically developed, are still heavily investing in energy-demanding sectors such as smart technologies, urban infrastructure, and research and development. Chongqing, traditionally an industrial city, continues to undergo substantial industrialization and urban expansion, further increasing its reliance on electricity consumption for growth. This observation is consistent with the findings of [35,36], who reported that in Western regions, energy consumption has a significant causal relationship with economic growth, while in Eastern and Central regions, this relationship is less pronounced. This pattern highlights the varying roles of electricity consumption in different stages of industrialization across China provinces, where more industrialized areas show diminishing returns from energy use, and less industrialized areas remain heavily reliant on electricity to drive economic growth.

However, if we do not consider the prior information, the provinces are classified into five groups, which consist of 2, 1, 1, 15 and 11 province(s) with the corresponding group-specific coefficients 0.6935, 0.8715, 0.9837, 1.0879 and 3.4351, respectively. This suggest that imposing the prior information helps to prevent overly divergent groupings, thus leading to more stable classifications. We also calculate the mean squared prediction errors (MSPE) of these two methods. Specifically, the observations of all individuals in the first 12 years are used as the training set, while the observations in the subsequent 7 years serves as the validation set. Based on the identified latent structures, we calculate the MSPE as

where , is the true observation and is the prediction value. As a result, the MSPE of our estimator is 0.8396, while the MSPE without prior information is 3.9443, much larger than our method. The reduced prediction error illustrates that incorporating prior constraint information can improve the predictive performance in latent structures identification for panel models.

6. Discussion

Identifying the latent groups structures in panel data analysis has recently attracted significant research interest. In this paper, we explore a pairwise fusion approach incorporating prior constraint information to identify the group pattern, and design an efficient ADMM algorithm to solve the optimization problem. Simulation studies and a real data application show that the proposed estimators outperform the existing approaches in terms of both detection accuracy and predictive performance. Our work still has its limitations; for example, how to obtain the prior constraint information in practical data analysis. Besides, our asymptotic results are built on the condition that the prior information is correctly specified; however, it remains to be explored when the prior information is misspecified.

There are some interesting issues that warrant further research. First, we only consider the commonly-used linear panel model with individual fixed effects. It is possible to adapt our proposed estimation framework to other panel models with latent group structures, such as the panel models with endogenous regressors [5] or the nonlinear panel models [19]. The specific objective function and estimation routine need to be re-examined. Second, the selection consistency property in Theorem 2 assumes that the true number of groups is fixed. It is appealing to consider a general framework that allows increases with the sample size. However, it may bring additional technical difficulties. Third, it is reasonable to allow for the presence of cross-section dependence in the current models. For such case, utilizing the factor structure [37] or interactive fixed effects [38] is potentially feasible but would require specific efforts. We leave these issues as our future research topics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and X.L.; data curation, M.L.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, Y.L.; methodology, M.L.; project administration, Y.L.; software, M.L.; supervision, Y.L.; validation, X.L.; visualization, Y.L.; writing original draft, X.L. and M.L.; writing review and editing, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This is work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2023JJ40453), Scientific Research Project of Education Department of Hunan Province (No. 23B0086), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72374071).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a publicly accessible repository: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj (accessed on 14 March 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

This appendix mainly contains the technical proofs and the test procedure for heterogeneity.

Appendix B. Proofs

Appendix B.1

Proof of Proposition 1.

Hence,

It holds that

Note that is strong convex and differentiable with respect to , as the Hessian matrix is positive definite. Together with the fact that is convex in , the sequence converges to a stationary point by directly applying the Theorem 4.1 of [39]. Thus we have

and

Moreover, for any , we have

Hence,

By the convexity of concerning , it then follows that

Therefore,

Since and from (A3), we have

So, . Combining with (A4), the proof of Proposition 1 is completed. □

Appendix B.2

Proof of Proposition 1.

We divide the proof of Theorem 1 into several steps:

Step 1: Define as the restricted subspace of where

Suppose that the true latent structure is known, the oracle estimator for is

and the oracle for denoted by is hence given by

Then we have the following lemma. □

Lemma A1.

Suppose that Assumption 1-2 hold. Then with probability , we have .

Proof of Lemma A1.

To prove Lemma A1, it is sufficient to show

where C is some positive constant. Let . For any event , we denote its complement as . By applying the Lemma A.1 in [26], we have:

It is obvious that

Hence, (A6) holds. Compared with Theorem 2 in [26], the oracle estimator of our method has a higher probability of to approach the true , while their method only has the probability . The underlying reason is that we take the concave pairwise fusion penalty to directly detect the homogeneity while [26] adopted the panel-CARDS procedures which required a good preliminary estimates for at first. □

Step 2: Let

be the minimal difference of the common coefficient between two groups. It is important to show the following lemma.

Lemma A2.

Suppose that the Assumptions in Lemma A1 hold. If and where , the objective function (5) has a local minimizer such that

Proof of Lemma A2.

Define

Recall the definition of in (A5). We define the following two mappings:

where is a vector consisting of K blocks with dimension p and the kth block is the common slopes of for , and . Obviously, when belong to , .

From (A7), we have . Define

Hence . We also consider a small neighborhood of :

From Lemma A1, there exists an event such that . For any , let . It is sufficient to show that is a local minimizer of with probability approaching 1. For this, we need to show:

- (1).

- In the event , for any and ;

- (2).

- There exists an event such that . Over the event , there exists a neighborhood of , denoted by such that for any and the inequality strictly holds when .

If both (1) and (2) hold, we have for any and , and therefore is a strict local minimizer of over the event .

We now prove the result in (1). We first show that equals a constant for any . Recall that . Let . Then for any k and m, we have

and

Then . By Assumption 2, is a constant on and therefore is also a constant on . So for all . Note that is strictly convex w.r.t and is the unique global minimizer of , then for all . From (A9), we have and . Hence for all . So (1) is obtained.

We next prove the result in (2). Let where is a positive sequence. For any , we have

By using Taylor expansion, we have

where lies between and for .

For , we have

For each , then and . Thus

Since and lies between and , then

For any , and ,

and hence by assumption 2. Since ,

By using the similar argument, it is easy to show that

Since

we have due to the concavity of . So

For , we let

where . Hence

Note that . By assumption 1, we have and . From (A11), we have . Hence there exists an event such that and over the set , . Then

By choosing sufficient small , we have and . Therefore, for any . The result in (2) is now completed.

Step 3: From Lemma A2, as and , we have and . By conditional probability formula, it yields that

as . Next, let be a Borel-measureable set, then

This means that shares a similar asymptotic distribution with , where

By Assumption 3, we have . Thus the results in Theorem 1 is obtained. □

Appendix B.3

Proof of Theorem 2.

For a given tuning parameter , denote the corresponding parameters estimator as and the mean square error as . Then

By the definition, , which approaches as by Assumption 5. For any , we identify two situations:

Case 1: Under-fitted model. Suppose that with . From Assumption 4, we have

Hence as .

Case 2: Over-fitted model. Consider any other such that . Following Lemma S1.14 in [5], we can obtain . Then by Assumption 5, we have

Combining Case 1 and Case 2 together, the information criterion in (18) can consistently select a optimal tuning parameter , which yields an oracle estimator for with probability approaching 1. □

Appendix C. Testing for Heterogeneity

It is important to determine whether the heterogeneity effect is statistically significant. The hypothesis of no heterogeneity can be represented by

against the alternative hypothesis

Under the null hypothesis, the model is

By applying the fixed-effect transformation, we have

where . The regression parameter can be estimated by OLS, yielding residuals , and the sum of squared errors , where and . The likelihood ratio test of is based on

where is the sum of squared errors using the latent structures model 2, and is the estimated number of groups. The residual variance is given by

However, the asymptotic distribution of is non-standard, making it challenging to tabulate critical values directly. To address this issue, we propose a residual-based bootstrap procedure to calculate the p-values. The detailed procedures are outlined in Algorithm A1.

| Algorithm A1: Residual bootstrap procedure |

|

References

- Hsiao, C. Analysis of Panel Data; Number 54; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme, S.; Manresa, E. Grouped patterns of heterogeneity in panel data. Econometrica 2015, 83, 1147–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Chen, Q. Testing homogeneity in panel data models with interactive fixed effects. Econom. Theory 2013, 29, 1079–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.; Sul, D. Transition modeling and econometric convergence tests. Econometrica 2007, 75, 1771–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Shi, Z.; Phillips, P.C. Identifying latent structures in panel data. Econometrica 2016, 84, 2215–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.T.; Fan, J.; Wu, Y. Homogeneity pursuit. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2015, 110, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Ke, Y.; Li, R. Homogeneity structure learning in large-scale panel data with heavy-tailed errors. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.J.; Zhu, Z. Quantile-regression-based clustering for panel data. J. Econom. 2019, 213, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, R. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2001, 96, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. Stat. Methodol. 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Jin, S.; Su, L. Identifying latent grouped patterns in cointegrated panels. Econom. Theory 2020, 36, 410–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Su, L.; Zhuang, Y. Detecting unobserved heterogeneity in efficient prices via classifier-lasso. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2023, 41, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Ju, G. Identifying latent grouped patterns in panel data models with interactive fixed effects. J. Econom. 2018, 206, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wang, X.; Jin, S. Sieve estimation of time-varying panel data models with latent structures. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabani, A. Estimation and identification of latent group structures in panel data. J. Econom. 2023, 235, 1464–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Bai, J. Panel data models with grouped factor structure under unknown group membership. J. Appl. Econom. 2016, 31, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Identification and estimation in panel models with overspecified number of groups. J. Econom. 2020, 215, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. Estimating multiple breaks one at a time. Econom. Theory 1997, 13, 315–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Su, L. Identifying latent group structures in nonlinear panels. J. Econom. 2021, 220, 272–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wang, W.; Xu, X. Identifying latent group structures in spatial dynamic panels. J. Econom. 2023, 235, 1955–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Phillips, P.C.; Su, L. Panel data models with time-varying latent group structures. J. Econom. 2024, 240, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.C.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Anderson, S.J.; Krafty, R.T. Incorporating prior information with fused sparse group lasso: Application to prediction of clinical measures from neuroimages. Biometrics 2019, 75, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jin, B. Pairwise fusion approach incorporating prior constraint information. Commun. Math. Stat. 2020, 8, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Sang, H. Spatial homogeneity pursuit of regression coefficients for large datasets. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2019, 114, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Z. Learning coefficient heterogeneity over networks: A distributed spanning-tree-based fused-lasso regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2024, 119, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Phillips, P.C.; Su, L. Homogeneity pursuit in panel data models: Theory and application. J. Appl. Econom. 2018, 33, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Parikh, N.; Chu, E. Distributed Optimization and Statistical Learning via the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers; Now Publishers Inc.: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, W. Structure identification in panel data analysis. Ann. Stat. 2016, 44, 1193–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Huang, J. A concave pairwise fusion approach to subgroup analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2017, 112, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.-J.; Kwon, S.; Choi, H. Homogeneity detection for the high-dimensional generalized linear model. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2017, 114, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-H. Nearly unbiased variable selection under minimax concave penalty. Ann. Stat. 2010, 38, 894–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, A.; Chernozhukov, V. Least squares after model selection in high-dimensional sparse models. Bernoulli 2013, 19, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, A.; Lam, P.-L. Electricity consumption and economic growth in china. Energy Policy 2004, 32, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-C.; He, Z.-X.; Long, R.-Y. Factors that influence carbon emissions due to energy consumption in china: Decomposition analysis using lmdi. Appl. Energy 2014, 127, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkemik, K.A.; Göksal, K.; Li, J. Energy consumption and income in chinese provinces: Heterogeneous panel causality analysis. Appl. Energy 2012, 99, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Fu, X.; Wang, S. Economic growth, electricity consumption, and urbanization in china: A tri-variate investigation using panel data modeling from a regional disparity perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. Estimation and inference in large heterogeneous panels with a multifactor error structure. Econometrica 2006, 74, 967–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Li, K.; Su, L. Panel threshold models with interactive fixed effects. J. Econom. 2020, 219, 137–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P. Convergence of a block coordinate descent method for nondifferentiable minimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2001, 109, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).