1. Introduction

Labor market rigidities affect macroeconomic response to shocks and the business cycle dynamics (see, for example, Nickell, Nunziata, and Ochel [

1]; Trigari [

2]; Barbier-Gauchard, Betti, and De Palma [

3]; and Morin [

4]). Gnocchi, Lagerborg, and Pappa [

5] demonstrate that labor market institutions, such as rigidities preventing the adjustment of real wages, play a significant role in business cycle fluctuations, based on an analysis of data from 19 OECD countries spanning 1971–2007. These empirical observations have important implications for both business cycle models and policymaking. Modeling wage restrictions is vital for understanding the economy, while real wage rigidities, such as collective bargaining, should be treated as endogenous due to their connection to macroeconomic dynamics.

Recent studies emphasize the importance of unionized labor market structures for the economy—for instance, Montebello, Spiteri, and Von Brockdorff [

6]; Perone [

7]; and Boeri and Jimeno [

8]. In most OECD countries, collective wage bargaining is a distinctive feature of labor markets, with considerable differences in the centralization of the wage bargaining process, ranging from highly centralized, such as Norway, to completely decentralized, such as the United States. In centralized countries, negotiations generally involve a few large labor unions that set wages at the national or industry/sectoral level (see, for example, Nickell, Nunziata, and Ochel [

1] and Visser [

9]). These sector-specific labor unions are known to consider broader economic conditions and internalize their wage settlements’ aggregate effects. Numerous studies have investigated the strategic interactions between wage setting and monetary policy (strategic monetary policy literature)—in a closed economy context, see, for example, Sidiropoulos and Zimmer [

10]; Di Bartolomeo et al. [

11]; Diana and Sidiropoulos [

12]; Cukierman and Lippi [

13]; Bratsiotis and Martin [

14]; Lippi [

15]; and Soskice and Iversen [

16]; in an open economy setting, see, for example, Acocella, Di Bartolomeo, and Tirelli [

17]; Coricelli, Cukierman, and Dalmazzo [

18]; Cavallari [

19]; Cuciniello [

20,

21]; and Cukierman and Lippi [

22].

However, these studies have not explicitly addressed the omission of large labor unions’ strategic interactions with policymakers in a

fully micro-founded model or built on a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) framework. Notable exceptions include Acocella et al. [

23]; Chrysanthopoulou and Sidiropoulos [

24]; Gnocchi [

25]; and Coricelli et al. [

26]. Nevertheless, the aforementioned studies are within a closed economy framework.

Incorporating large unions’ strategic interactions with policymakers into a fully micro-founded DSGE framework is crucial for understanding their impact on macroeconomic stability, policy effectiveness, and equilibrium determinacy. This is particularly important beyond merely understanding unions’ strategic behavior in an open economy for various reasons. First, a fully micro-founded DSGE framework incorporates the intertemporal decisions of agents, ensuring that large unions’ strategic wage setting is endogenously linked to aggregate macroeconomic dynamics. Without this, existing models risk overlooking second-round effects and how these strategic interactions contribute to business cycle fluctuations and macroeconomic stability. Second, unlike partial equilibrium or static models used by earlier contributions, a DSGE approach allows for feedback loops where unions’ wage setting affects monetary policy, which in turn influences employment, inflation, and income—ultimately shaping unions’ future decisions. Third, existing models (e.g., Cuciniello [

21,

27]) examine the strategic behavior of large unions in open economies but do not systematically address how these interactions affect equilibrium determinacy (i.e., whether the economy has a unique, stable equilibrium). A fully micro-founded DSGE framework ensures that the determinacy conditions are explicitly incorporated, avoiding multiple or indeterminate equilibria that could lead to self-fulfilling expectations and policy inefficacy.

Therefore, early contributions in a fully micro-founded DSGE model overlook potential interactions between the economy’s openness, large unions, and monetary policymakers. This is paradoxical, given that historically, agreements between the government and social partners have played a significant role in policymaking, particularly as part of disinflation strategies to address the challenges of globalization and monetary unification in Europe (see, for example, Avdagic [

28]; Avdagic and Visser [

29]; and Ceron, Curini, and Negri [

30]).

In this paper, we address this inconsistency. We focus on whether and how macroeconomic institutions and open economy parameters may affect the framework for monetary policy analysis in an open economy, i.e., the aggregate dynamics of the economy, the conditions for the existence of a unique rational expectations equilibrium, and the economy’s dynamic response to shocks.

To this end, we construct a small open economy DSGE model with monopolistic competition, nominal rigidities, and a unionized labor market. The model comprises representative households, intermediate and final goods-producing firms, a central monetary authority, and large labor unions that engage in centralized wage bargaining. Open economy features include imperfect capital mobility and imported consumption goods, as well as exchange rate dynamics driven by uncovered interest parity. Households maximize intertemporal utility derived from consumption and disutility from labor. Firms operate under monopolistic competition and Calvo-type price stickiness. Intermediate goods producers hire labor from a centralized unionized labor market to produce output. A subset of firms re-optimize prices each period. Labor unions set nominal wages, internalizing the effect of wage outcomes on the economy.

We extend the open economy New Keynesian DSGE model by incorporating the interactions between large unions and the monetary authority operating under different interest rate rules. Specifically, the policy rate may react to home inflation, output gap, and/or real exchange rate fluctuations. A DSGE framework allows for a comparative dynamic analysis, showing whether certain policies lead to self-reinforcing wage pressures, unemployment persistence, or excessive exchange rate volatility. Unlike the standard case of atomistic unions—small unions whose individual decisions do not impact on aggregate outcomes— large unions anticipate that their wage demands lead to higher marginal cost, optimal prices, and aggregate price index for home goods. This, in turn, affects output and employment through three channels. First, fluctuations in target variables trigger a monetary response from the central bank. Nominal interest rates change, and consumption, output, and employment change, too. We refer to this as the monetary policy effect. Notably, the monetary policy response is heterogeneous and conditional on the specific policy target. For instance, an anti-inflationary monetary authority will raise nominal interest rates to curb home inflation. In contrast, an accommodative monetary authority, prioritizing output stabilization, will focus more on mitigating output fluctuations. Second, changes in home inflation alter the expected home inflation rate in the next period, changing real rates and consumption, output, and employment. This is the intertemporal substitution effect. Third, according to the open economy effect, wage-driven price increases provoke real appreciation, reducing demand, but higher exports and risk-sharing partially offset this.

These are the key effects that large unions internalize when adjusting their wage demands in response to policy actions and external conditions. Wage moderation hinges not only on central wage bargaining but also on monetary policy regimes and open economy parameters. In our setting, a monetary authority concerned about output and/or exchange rate stability induces unions to be more aggressive in their wage requests, while the opposite holds (moderation of wage claims) when the monetary policy reacts to variations in inflation. A high degree of openness and strong substitutability between domestic and foreign goods result in more moderate wage claims.

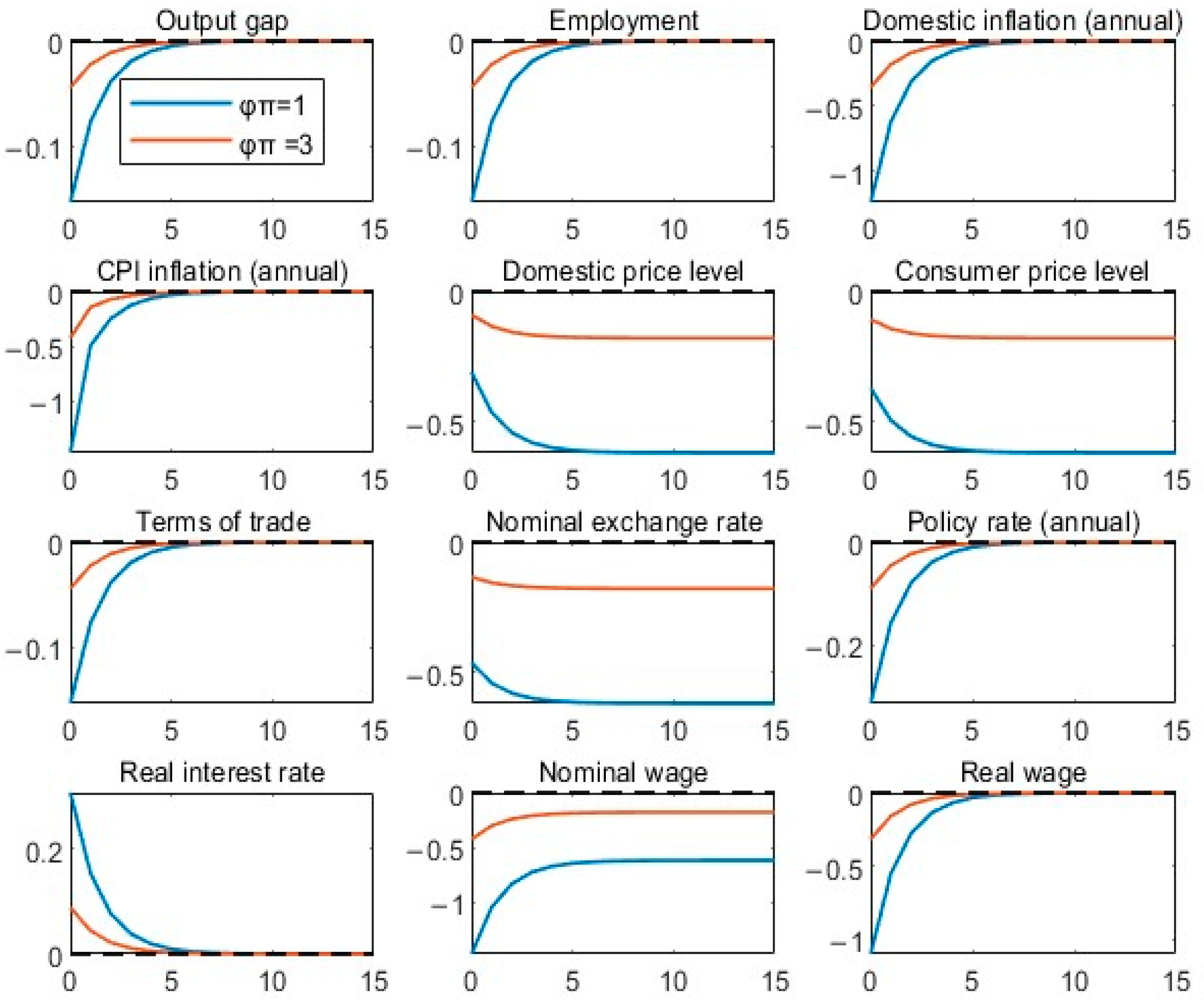

Interestingly, this novel wage-based mechanism alters the New Keynesian Phillips curve, with implications for the conduct of monetary policy, particularly in shaping the economy’s response to shocks and equilibrium determinacy. To illustrate the quantitative relevance of this novel wage mechanism under various monetary policy regimes, we analyze its impact on the equilibrium values of key endogenous variables. These values are computed analytically and numerically in response to a temporary monetary policy shock. We find that the equilibrium is contingent on interactions among large unions, the economy’s openness, and monetary policy regimes through the internalization effect. Additionally, since the slope of the New Keynesian Phillips curve is steeper than in the standard case of atomistic unions, the effects of a monetary policy shock are amplified relative to the standard case of atomistic unions.

This paper also demonstrates that unionized labor markets play a crucial role in shaping the determinacy properties of the rational expectations equilibrium across different monetary policy frameworks and timing. Determinacy refers to the uniqueness of the rational expectations equilibrium. It ensures that the model yields one forward-looking solution path in response to shocks, avoiding sunspot equilibria and policy ineffectiveness (Blanchard and Kahn [

31]). Our study establishes conditions for ensuring uniqueness and local stability of equilibrium. In open economy New Keynesian models, equilibrium outcomes are influenced by the interaction between monetary policy rules, trade openness, and labor market structures. The central bank’s response to domestic inflation—critical for preventing indeterminacy and instability—depends on the internalization behavior of large unions, key open economy dynamics, and policy parameters.

This paper contributes to the literature by explicitly incorporating unionized labor market structures—via the wage-setting behavior of large unions—into a small open economy DSGE framework. It bridges two strands of macroeconomic research: the strategic monetary policy literature (e.g., Coricelli, Cukierman, and Dalmazzo [

18]; Cavallari [

19]; and Cuciniello [

20,

21]) and open economy monetary policy within DSGE settings (e.g., Gali and Monacelli [

32]). This paper offers new insights into how union coordination interacts with monetary policy regimes and trade openness to shape macroeconomic stability and the dynamic behavior of the economy. These findings enhance our understanding of monetary policy design in economies with strong labor institutions and external trade exposure—an area that remains underexplored in the existing DSGE literature.

The study by Juvonen [

33] is the closest to the analysis presented in this paper as it examines wage-setting coordination in a two-sector, open economy dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model. The main difference from our study is that Juvonen’s analysis focuses on the impact of strategic interaction between the tradable and non-tradable sectors on steady-state allocations and the dynamic behavior of the economy.

This paper’s organization is as follows: In

Section 2, we outline our small open economy model with large unions.

Section 3 analyzes the large unions’ internalization effect under openness and different monetary policy settings.

Section 4 discusses the modified aggregate dynamics, i.e., we look at how interactions between large unions and monetary policy in an open economy affect the behavior equations of our model.

Section 5 examines the real effects of interactions among unions, openness, and central banks under different interest rate rules.

Section 6 analyzes the conditions under which the rational expectation equilibrium is determined.

Section 7 concludes the paper.

3. The Internalization Effect Under Openness and Different Monetary Policy Settings

In this section, we elaborate on the internalization effect—large unions’ capacity to internalize the macroeconomic consequences of wage hikes—in an open economy setting and under different monetary policy rules.

For

, each large union internalizes the effect of its wage decision to a series of aggregate variables, such as domestic inflation, employment, etc. As in Gnocchi [

25], we assume that unions compute these elasticities by taking as given the expectations about variables in the next period and looking at the log-linearized first-order conditions.

In a symmetric equilibrium, each large union anticipates that

The union’s ability to internalize the consequences of its own actions on aggregate nominal wage is proportional to union size. For a similar result in a closed economy framework, see Bratsiotis and Martin [

14]; Lippi [

15]; and Gnocchi [

25]; while for an open one, see Cuciniello [

20,

21,

27]. Conversely, under the assumption of atomistic unions, i.e.,

, the internalization effect disappears.

Interestingly, the incentive to moderate or not wage claims relies on the elasticity of labor demand perceived by the

-th union for each of its members,

. For

, each union perceives that its wage influences labor demand for each of its members through two channels, represented by the two terms of the R.H.S of Equation (35).

The elasticity of labor demand perceived by the z-th union

is the weighted combination of two effects. First, the

substitution effect, captured by

, reflects that a higher wage of the z-th union relative to the wage of other unions leads firms to substitute away from its labor varieties (e.g., Lippi [

15] and Cukierman and Lippi [

22]). Second, the

output effect is represented by the elasticity of aggregate labor demand to the real consumer wage of the

-th union,

(e.g., Coricelli et al. [

26] and Bratsiotis and Martin [

14]).

As will be demonstrated later,

differs from the one found in the relevant New Keynesian literature (e.g., Gnocchi [

25]; Cuciniello [

21]; Chrysanthopoulou and Sidiropoulos [

24]) in two respects. First, conditional on the assumed monetary policy rule, the effect of wage hikes on aggregate labor demand might be either positive or negative. Second, in an open economy context,

incorporates the concern of large unions for the economy’s external sector. Therefore, there is a novel mechanism in an open economy context, which we label

open economy effect.

When the monetary authority is concerned only with variations in inflation, i.e.,

is equal to

where

Θ if

and

are sufficiently high. Also, the elasticity of

with respect to

is given by

Each union realizes that a wage hike leads to higher marginal cost and, hence, higher prices for those firms that are able to re-optimize in each period. Consequently, the aggregate price index for home goods rises, too. This increase in negatively impacts output and employment through three effects.

First, the increase in

, due to the inflationary wage rise, triggers the anti-inflationary monetary authority’s response through (27a). This rise of the nominal interest rate results in lower consumption, output, and employment. This is the

monetary policy effect, represented by the term

in Equation (36). Gnocchi [

25] and Chrysanthopoulou and Sidiropoulos [

24] find a similar effect.

Second, the increase in

affects the real interest rate

and thus the intertemporal plans for consumption. Lower current aggregate demand lowers output and employment. This is the

intertemporal substitution effect, captured by the term

, as in Chrysanthopoulou and Sidiropoulos [

24]).

Yet, in an open economy, there is an additional effect, which we label the open economy effect This effect, captured by the term in Equation (36), operates through trade unions’ concern about the economy’s external sector. This effect incorporates (i) the expenditure switching effect and (ii) the effect on consumption through the risk-sharing condition, seen in Equation (17). According to the expenditure-switching effect, each union recognizes that wage increases—by driving up the prices of domestic goods—lead to a substitution effect, where consumers in the home country (union members) shift from the now more expensive domestic products to relatively cheaper foreign alternatives. Additionally, increases in driven by wage pressures through Equation (13) raise , causing real appreciation. This real appreciation affects domestic consumption through the risk-sharing transfer of resources (Equation (17)), ultimately reducing aggregate demand and domestic economic activity. However, this decline is partially or fully offset by a positive direct demand effect from higher exports, as increased total consumption in a foreign country boosts its demand for home-produced goods. Additionally, there is a positive effect on domestic consumption linked to international risk-sharing, given the implied higher world consumption.

Two additional comments are worth noting. First, the sign of the open economy effect depends on the relative magnitude of Θ and, consequently, on and . The contractionary (expansionary) effect prevails when (), meaning that if and are sufficiently high, the contractionary effect dominates, which is the assumption made in this analysis. Second, the open economy effect is more substantial the more open the economy is (high values of ) and is more important when wage bargaining is more centralized (high values of ). In both cases, the internalization effect is stronger, and are higher, increasing the incentive to moderate wages.

Under baseline parameter values (see

Section 2.6), it is easy to show that

, and thus the incentive to moderate wages, is an increasing function not only of the degree of central wage setting,

, but also the degree of openness in the economy,

, and other open economy parameters such as

and

and the degree of monetary policy anti-inflationarity,

. Formally,

This dependence of on , , and is of vital importance to the model; because of this, institutions affect labor supply (wage-setting equation) and consequently, the aggregate dynamics (New Keynesian Phillips curve).

Note that when the monetary authority is concerned only with variations in output, i.e., (27b), then

is given by (39).

, and consequently, large unions’ incentive to moderate wages, relies not only on the intertemporal substitution effect and the monetary policy effect, captured by the term , but also on the open economy effect and the monetary policy effect, represented by the term in Equation (39). Both the intertemporal substitution effect and the open economy effect decrease output, triggering the output-responsive (accommodative) monetary policy to lower the interest rate to boost output. The successive is getting smaller, ensuring that the sum converges.

In this particular case,

is negatively associated with the degree of monetary policy accommodation,

, since the negative impact of wage demands on employment (either through the real interest rate or the open economy effect) triggers the countercyclical monetary policy [through the policy rule (27b)]. The monetary authority decreases nominal interest rate, leading to higher output, and hence, employment. Therefore, a higher degree of monetary policy accommodation,

, is associated with lower values of

and, thus, with aggressive wage hikes. This is the exact opposite of the result obtained in the case of strict inflation targeting.

In the case of the canonical current Taylor rule, i.e., (27c), we obtain that

equals

Aside from the anti-inflationary policy effect and the output-responsive policy effect expressed by the term and the intertemporal substitution effect and the monetary policy effect, , there is also the open economy effect and the monetary policy effect represented by the term . It can be easily shown that high values of moderate wage hikes as , whereas high values of have the opposite effect since

When the central bank follows a current Taylor rule augmented with exchange rate, i.e., (27d),

is given by

In this case, there is an additional effect relative to Equation (41). Each union recognizes that wage increases—by driving up the prices of domestic goods—lead to an increase in the overall price level (). As a result, and through Equation (14), the real exchange rate depreciates (), which triggers a monetary policy response, leading to a reduction in the nominal interest rate. The reduction in the interest rate stimulates consumption, which subsequently boosts output and employment. The additional term in Equation (42) represents the exchange rate effect and the monetary policy effect. Notably, this term has a positive sign—in contrast to the other terms. Therefore, when the central bank responds to exchange rate movements, might be positive or negative. For low values of the exchange rate coefficient, i.e., , remains negative. The opposite holds for , and turns positive.

Lastly, when the central bank follows a forward-looking version of the Taylor rule, equals (39) since unions compute elasticities, taking as given expectations about variables in the next period.

Proposition 1. Wage moderation depends not only on but also, through , on the open economy parameters, and . Additionally, the impact of monetary policy on wage-setting behavior is not uniform across different policy regimes, since the monetary policy coefficients ( ) have a different impact on wage claims. While strict inflation targeting may amplify certain effects, output-responsive or exchange rate-inclusive rules introduce additional complexities for policymakers.

Independently of the monetary policy regime, it can be easily shown that when unions’ wage demands consider the open economy effect. Unions’ wage claims are more aggressive in an open economy than in a closed one.

4. Equilibrium Dynamics: A Canonical Representation

Log-linearizing the model around the non-stochastic steady state allows to fully characterize the equilibrium dynamics at a first-order accuracy. The model consists of the following equations: the IS curve, which represents the demand side; the aggregate supply curve, often called the New Keynesian Phillips curve (NKPC); a relationship between terms of trade and output and exchange rate; and a simple (i.e., non-optimized) monetary policy rule. The IS curve is

where

is the output gap, and

denotes the natural output (or flexible-price output). Thus,

assesses the extent to which the output differs from the flexible-price equilibrium output due to the nominal inertia present in the model. Also,

and

if

and

are sufficiently high. Note also that inserting for

from

(this is Equation (29) in Gali and Monacelli [

32]), and taking into account that

is exogenous to domestic allocations, the IS curve can be written as

where

is the natural (flexible) real rate, which is equal to

Equation (43b) shows that the output gap depends on expectations about its future value and a term reflecting the real interest rate gap. Also,

. Equation (43b) is the standard IS curve in the open economy (Gali and Monacelli [

32]).

It can be easily shown that there is an equivalence between

and

:

In addition, the real exchange rate is related to the terms of trade according to the following equation:

As for the monetary policy rule tracked by the central bank, we consider a variety of simple policy rules given by the Equation (27a)–(27e).

The New Keynesian Phillips curve is given by

Expression (47) states that the current home inflation rate, , is determined by the output gap, , and expected home future inflation,

Interestingly, this is a modified New Keynesian Phillips Curve. The modification is due to large unionized labor markets (

). The New Keynesian Phillips curve slope,

, Equation (48), through

, is determined by the interactions between large unions, the economy’s openness, and the monetary policy regimes.

where

Note that by iterating Equation (48) forward to the infinite future, we observe that monetary policy indirectly influences inflation through the expectations channel. Equation (49) illustrates the impact of the expected future stream of output gaps on the current level of home inflation. This impact is conditional on the internalization effect of large unions. An anticipated future economic expansion would increase domestic inflation today in proportion to large unions’ wage claims.

It is more likely that large unions’ wage claims become more aggressive, and consequently, the New Keynesian Phillips curve becomes steeper, when

(i.e., the degree of openness in the economy) is lower. As we have already mentioned, in our setting, openness in the economy may, however, discourage wage demands through the open economy effect. Additionally, the higher

is (i.e., the degree of wage-setting centralization), the more aggressive large unions’ wage claims and the steeper the New Keynesian Phillips curve. The same result holds in a closed economy. For instance, see Gnocchi [

25] and Chrysanthopoulou and Sidiropoulos [

24]. However, the steepness of the New Keynesian Phillips curve is not uniformly linked to the monetary response; rather, it depends on the specific reaction of the central banker. If the monetary authority focuses solely on inflation, then

is negatively related to

. However, when the monetary authority also considers output and/or exchange rate fluctuations, the relationship reverses, with

being positively related to

and

.

Proposition 2. In an open economy with large unions, the slope of the New Keynesian Phillips curve depends on the incentive for wage moderation and, hence, on the various characteristics of institutions and the open economy parameters. Formally, in an open economy with large unions, we obtain

Proposition 2 has significant implications for the economy’s response to shocks and the formulation of monetary policy. The following two sections analyze these issues.

6. Determinacy of the Rational Expectations Equilibrium

The concepts of equilibrium uniqueness and multiplicity have been central to rigorous discussions and ongoing research in the economics literature. Determinacy pertains to the conditions under which a dynamic system follows a single, well-defined equilibrium trajectory. Multiple equilibria may arise in DSGE models when the conditions for a unique rational expectations equilibrium are not met—typically due to weak monetary policy responses. In such cases, the model becomes indeterminate, meaning agents’ expectations are not uniquely pinned down by fundamentals and can lead to self-fulfilling outcomes (so-called sunspot equilibria). This undermines the stabilizing role of monetary policy and introduces greater macroeconomic volatility.

In this section, we extend the literature on determinacy issues of New Keynesian open economy models. This literature has heavily relied on the degree of trade openness; see, for example, De Fiore and Liu [

49]; Karagiannides and Liambas [

50]; and Clarida et al. [

39]. Clarida et al. [

51] and Taylor [

52] argue that responding to real interest rates can be destabilizing. Froyen and Guender [

53] emphasize the role of exchange rates, whereas Barnett and Eryilmaz [

54] note that open economies exhibit complex behaviors, complicating policy design.

In our framework, a key research question is whether the interactions between large unions and monetary policy in a small open economy influence equilibrium determinacy. Based on Blanchard and Khan’s [

31] methodology, we analyzed the determinacy properties of the basic Taylor rule, covering a range of specifications from simple (current and forward) inflation targeting and simple output targeting to the canonical (current and forward) Taylor rules. This methodology relies on the number of eigenvalues inside the unit circle, given the number of non-predetermined variables of the model. By rearranging the Equations (28), (43b), (45)–(47), and (27a)–(27e), we first write the system in the form

, where

are the non-predetermined variables, and

denotes the exogenous disturbances. For a first-order stochastic difference equation system with two equations in domestic inflation and the output gap, the Jacobian matrix

C characterizes the system’s dynamics. The eigenvalues

and

are obtained by solving the characteristic equation

. This gives a second-order characteristic polynomial,

. For a unique and stable solution, both eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix C must lie outside the unit circle, meaning their modulus must be greater than one (Blanchard and Kahn [

31]). According to the Schur–Cohn criterion, this condition holds if and only if both of the following two conditions are fulfilled:

and

.

6.1. Strict Inflation Targeting and Determinacy

The central bank is assumed to follow an interest rate rule of the form (27a), reacting to current inflation. Thus, the model consists of Equations (28), (43b), and (47), together with policy (27a). Substituting Equations (27a)–(43) for

and rearranging the terms, the system can be written in the form

,

Notice that there are two endogenous variables: inflation rate,

and output gap,

. There is no predetermined variable in the model. To verify that

is the unique solution, we need to check the determinacy properties of the system Equation (83). In accordance with Blanchard and Kahn [

31], under a current inflation-targeting rule, the equilibrium determinacy of system Equation (83) obtains if and only if monetary policy is

active (Leeper [

55]). That is,

The Taylor principle prescribes the necessary and sufficient condition for equilibrium determinacy. The monetary authority should increase the nominal interest rate by more than one-for-one in response to a rise in inflation to avoid multiple equilibria and control inflation. Note that the determinacy region does not depend on structural parameters of the model. However, this is not always true.

6.2. Strict Output Targeting and Determinacy

We might assume that the monetary authority reacts to variations in current output gap. The model consists of Equations (28), (43b), and (47), together with policy (27b). After proper substitutions and rearrangements, the system can be written in the form

,

Following Blanchard and Kahn [

31], the system (85) has a unique equilibrium solution for the output gap and the inflation rate if and only if the number of the matrix C’s eigenvalues that are outside the unit circle is equal to the number of forward-looking (non-predetermined) variables, which is two. Then, with a current-looking rule of the form (27b), the open economy New Keynesian model described by system Equation (85) has a unique stationary equilibrium if and only if

The interest rate should not respond too vigorously to changes in output as this leads to an indeterminate rational expectations equilibrium when the New Keynesian Phillips curve is flatter (low values of . In our model, the latter is true for low values of or/and or for higher values of and

6.3. Current Taylor Rule and Determinacy

In this section, we assume that the central bank reacts to both current domestic inflation and output gap. The model consists of Equations (28), (43b), and (47), together with policy (27c). Substituting Equations (27c)–(43) for

and rearranging the terms, the system can be written in the form

,

For equilibrium determinacy, the number of eigenvalues of

C outside the unit circle must equal the number of non-predetermined endogenous variables (Blanchard and Kahn [

31]). In this case, there are two non-predetermined endogenous variables. According to the Schur–Cohn criterion, both eigenvalues of C are outside the unit circle if the following conditions are fulfilled:

Higher values of the output coefficient allow the central bank to react only weakly (less aggressively) to inflation for the equilibrium to be determined. Similarly, a lower (NKPC slope) enables the monetary authority to react less aggressively to inflation for the equilibrium to be determined. In our model, a lower is associated with lower values of or/and or with higher values of and .

6.4. Taylor Rule Augmented with Exchange Rate and Determinacy

The Taylor rule has been augmented with an exchange rate target, in addition to output and inflation, to account for the significant role exchange rate fluctuations play in open economies, influencing inflation dynamics, external competitiveness, and financial stability. In this case, the model consists of Equations (28), (43b), and (45)–(47), together with the interest rate rule (27d). After proper substitutions and rearrangements, we can write the system of equations in the form

as follows:

As before, we examine the determinacy conditions of the system Equation (89). There are two non-predetermined variables,

and

. Given monetary policy based on the current-looking Taylor rule augmented with the exchange rate, the open economy New Keynesian model described by the system Equation (89) has a unique stationary equilibrium if and only if

It is worth stressing that including exchange rate (as well as output) targeting increases the options available to the monetary authority. Even a small exchange rate coefficient allows the central bank to react only weakly to inflation (to be less aggressive). Again, the range of determinacy varies with large unions’ internalization effect.

6.5. Forward Taylor Rule and Determinacy

A Taylor rule with current-looking output but forward-looking inflation targeting, i.e., (27e), provides a reasonably good description of the way major central banks around the world behave (Clarida, Gali, and Gertler [

37]). In this case, we can write the system in the standard form,

Following Blanchard and Kahn [

31], the system Equation (91) has a unique equilibrium solution for the output gap and the inflation rate if and only if in terms of the monetary coefficient it must be the case that

Monetary policy has both an

upper and a

lower bound for the rational expectations equilibrium to be unique (equilibrium determinacy). The upper bound, 1+

, implies that the interest rate should, however, not respond too vigorously to changes in domestic inflation expectations, as this could lead to an indeterminate rational expectations equilibrium. Bernanke and Woodford [

56] discuss this property of expectation-based policy rules in detail.

Targeting output in addition to inflation impacts both these bounds. In addition, both these bounds are functions of the interactions among openness, large labor unions, and monetary policy through the composite parameter .

Proposition 4. The determinacy of rational expectations equilibrium in open economy New Keynesian (NK) models depends on the interplay between monetary policy rules, trade openness, and labor market structures. The extent to which the monetary authority responds aggressively to domestic inflation to prevent indeterminacy and explosive solutions is influenced by the internalization effect of large unions and, consequently, by open economy parameters and monetary policy coefficients.

7. Discussion

In centralized wage bargaining systems, a few large unions negotiate wages at the national or sectoral level (Visser [

9]). However, general equilibrium models have typically assumed the presence of atomistic unions, thereby neglecting potential interactions between policy and labor union decisions. This study extends the open economy New Keynesian framework by incorporating the strategic interactions between large labor unions and monetary policy, demonstrating their impact on macroeconomic stability, monetary transmission mechanisms, and equilibrium determinacy.

One key insight is that monetary policy regimes influence union wage demands, shaping inflation dynamics and output fluctuations. Under strict inflation targeting, unions moderate wage claims due to the stronger disciplinary effect of monetary policy. Conversely, when the central bank prioritizes output stabilization or reacts to exchange rate fluctuations, unions pursue more aggressive wage demands, amplifying inflationary pressures. This highlights the importance of policy coordination in economies with centralized wage bargaining, where the central bank’s stance can alter unions’ incentives and macroeconomic outcomes. Moreover, unions perceive the impact of wage increases on external competitiveness and domestic demand and consequently alter their wage behavior. Therefore, policy frameworks must consider the openness of the economy in unionized economies, as trade integration alters shock transmission and equilibrium conditions.

In summary, this study has suggested the stabilization role of institutions, particularly a concentrated labor market in an open economy with heterogeneous monetary policy regimes, when large unions take the external sector into account. It would be interesting to allow for a non-trivial policy problem and characterize the optimal monetary policy in a fully micro-founded open economy framework (as in Gali and Monacelli [

32] and Gali [

35]), incorporating unionized labor markets and sectoral wage bargaining.

We acknowledge that the real-world behavior of trade unions is influenced by institutional heterogeneity and political dynamics. Institutional heterogeneity includes variations in wage bargaining structures (e.g., at the firm, sector, or national level), union density and coverage, coordination mechanisms, and legal frameworks governing collective bargaining. Political dynamics may include government ideology, the presence of tripartite structures, political cycles, and broader historical or social trust conditions that shape labor relations (e.g., severe crisis). These factors can critically affect the extent to which unions internalize macroeconomic constraints, such as trade openness or policy targets. For instance, in times of severe crisis (e.g., Eurozone debt crisis, COVID-19), governments may appeal to “wage moderation in the national interest.” Unions may accept lower wage growth if trust and cooperation with government are strong. Governments may also decentralize wage bargaining (e.g., Italy, Greece under structural adjustment programs). This weakens centralized union coordination, leading to more fragmented wage outcomes and potentially more inflationary pressure. This, in turn, may affect the degree of the internalization effect assumed in our model. Exploring how such institutional diversity interacts with monetary policy regimes remains a promising avenue for future research and could form the basis of a separate theoretical and/or empirical study.

This study provides a theoretical exploration of the interaction between unionized wage setting, trade openness, and monetary policy regimes. However, the model is not empirically estimated and has not been validated against real-world data. Future research could address this by estimating the model using structural Bayesian methods and incorporating cross-country data on union behavior, wage coordination, and openness. Empirical validation using panel data from economies with varying degrees of openness and union influence would further help assess the robustness of the theoretical predictions. This is a further possible extension that we leave for future research.