More generally, under certain conditions, we can prove that the action of the EH group on is doubly transitive.

Proof. Similar to the proof of Proposition 3, we assign a lexicographic order to the set : column-wise from left to right and top to bottom in each column. Let S be the smallest tableau in this order. Let Z be the Young tableau obtained by filling the boxes row-wise from top to bottom and from left to right in each row. By using induction on the size of the Young diagram, we can see that Z is the largest tableau in the lexicographic order.

To establish the doubly transitivity of the EH group action, it is sufficient to prove that any Young tableau can be transformed into S by an EH group element while preserving the Young tableau Z. Actually, it is enough to prove that for any Young tableau , there exists an EH group element that moves T to a tableau smaller in the lexicographic order, with fixing the tableau Z. Since this process is finite, it will eventually stop, with the final tableau being S, while the tableau Z remains unchanged.

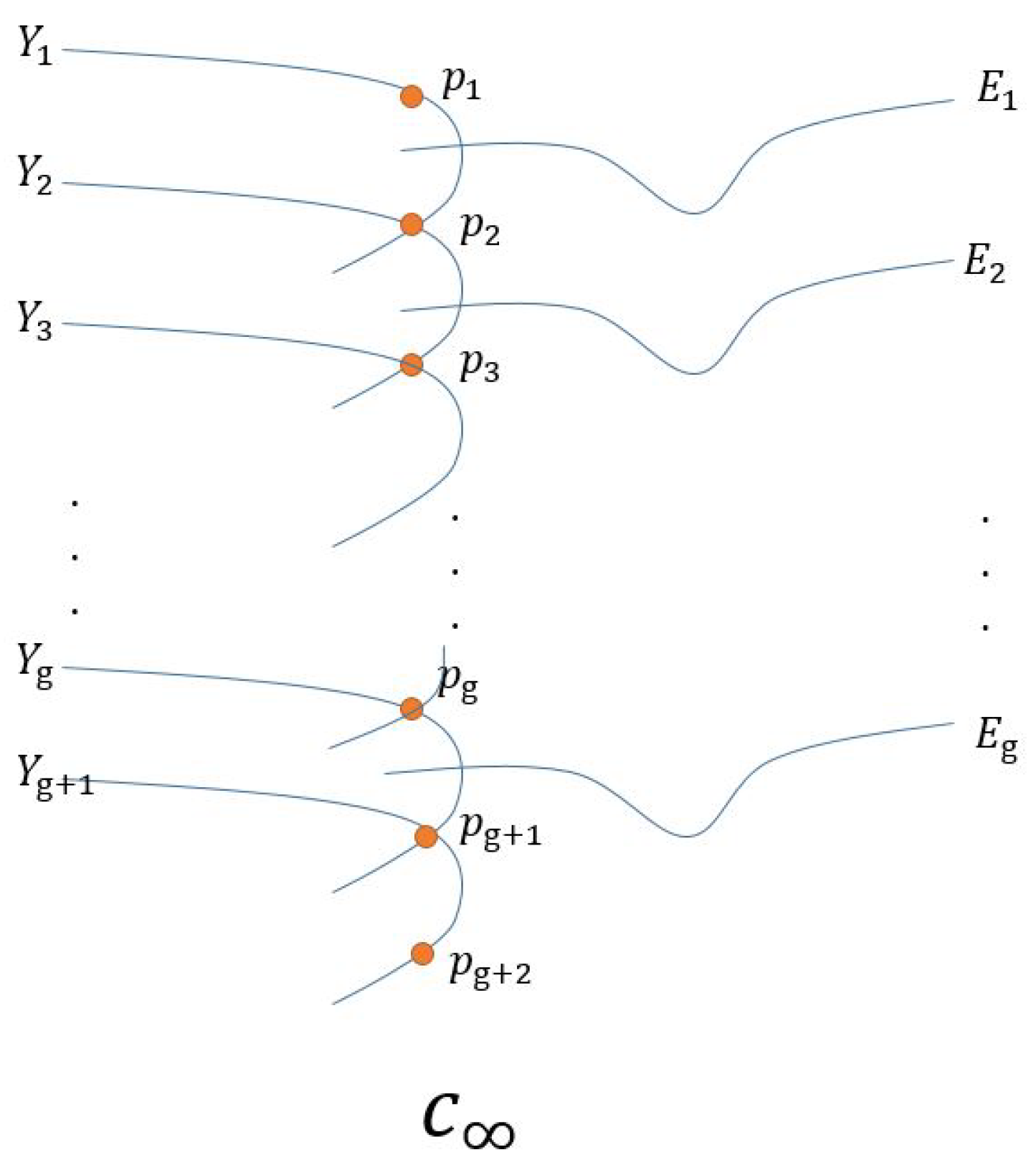

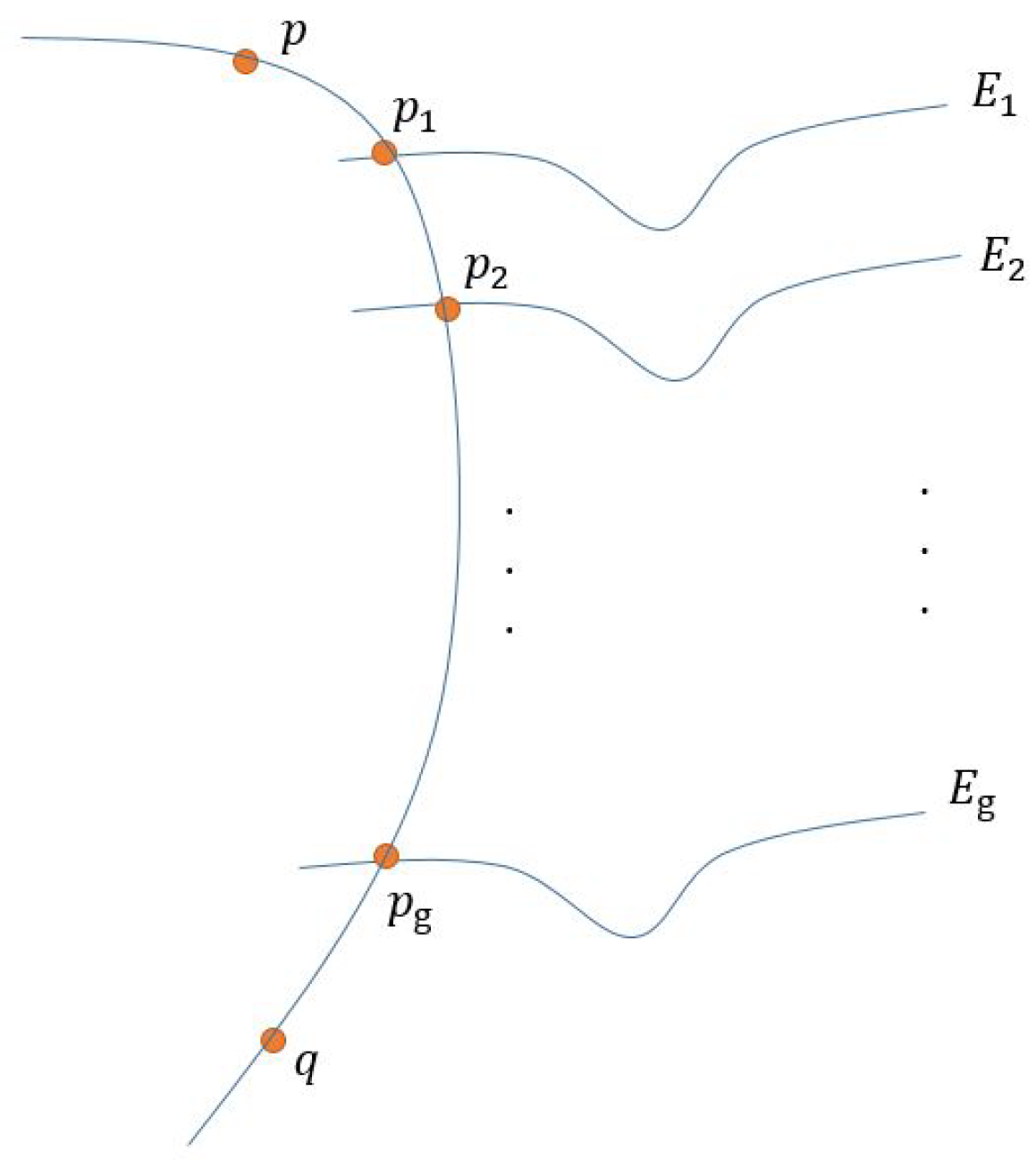

Given a Young tableau

, let

be the first integer in the lexicographic order that differs from

S. Let

represent the integer in the box located at the

i-th (starting from 1) row from top to bottom and the

j-th (starting from 1) column from left to right in tableau

T. The integer

M cannot appear to the left of or above the box containing

, because at these positions,

T and

S are identical, and

is the first different integer. Therefore,

M can only lie above and to the right of

. Let

,

. We denote their distance as

We aim to exchange

M with

in

T, while keeping

Z fixed, so that

T becomes a Young tableau with a smaller lexicographic order. If

M and

are in the same row in

Z, then the group action

is sufficient to achieve this. Therefore, we only need to consider the case where

M and

are not in the same row. Let us assume

M is at the end of the

i-th row and

is at the beginning of the

-th row in

Z. If the distance between

M and

in

Z is not equal to

L, i.e.,

then the group action

can exchange

M with

in

T while fixing

Z. Therefore, in the following proof, we always assume

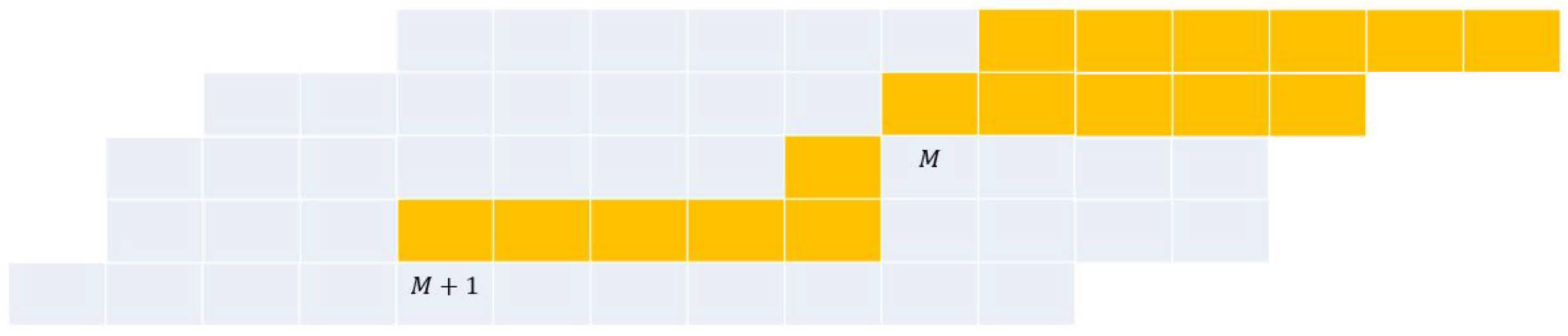

Now we consider the position of and let . Then the possible positions of are as follows:

- (1)

;

- (2)

;

- (3)

;

- (4)

;

- (5)

.

Case 1: If

, we can use the group action

to exchange

M with

. Since

is in the same row as

M in

Z,

fixes

Z. Then, we apply the group action

to exchange

M with

in

T. Given that

the action

fixes

Z. Thus, the composition of these two group actions exchange

M with

in

T while keeping

Z unchanged.

Case 2: If

, the proof follows a similar approach to that in Case 1. First we use the group action

to exchange

M with

while maintaining

Z. Subsequently, we apply the group action

to exchange

M with

in

T. Since

the action

fixes

Z. Therefore, the composition of these two group actions achieves the goal.

Case 3: If

, meaning

and

are in the same column, then

must be directly above

. If not,

M would also have to be positioned between

and

, contradicting our assumption. In this case,

M must be positioned in one of the upper-left corners of the columns to the right of the column containing

. This is because the smallest integer in these columns is

M. Additionally, according to Assumption (1), we have

which is a contradiction. Therefore, this case cannot occur.

If , indicating that is in one of the columns to the left of , then M must be in the first box of the column it belongs to. As in the previous case, M must be in one of the upper-left corners of the columns to the right of the one containing . Thus, by using a similar argument, we arrive at a contradiction in this case as well.

Case 4: If

, i.e.,

is above

M, then it must be adjacent to

M; otherwise, there would be no integer between

and

M to fill in. In this case, we can first exchange

M with

in

T using

. Note that this exchange also affects

M and

in

Z. Next, we exchange

and

M in

using

. Since

and

M in

are separated by a distance of

, they remain unchanged in

. Finally, we exchange

M with

in

using

, resulting in

while

and

M in

are in the same column and thus remain unchanged. Therefore,

fixes

Z and reduces

to

in

T, hence

This process does not require the conditions.

Case 5: If is in the same row as M, then must be adjacent to M. Note that we have already addressed Case 3, so we assume . In this case, we consider the position of . If is also in the same row and adjacent to , we continue this process with , and so on, until we find such that M are consecutive in the same row, but is not. Let . Since , it must be that .

Subcase 5.1: If

, meaning that

is in the same column as

, then

must be adjacent to

, as the integers

are not in this column. Therefore,

, which means

and

M are in adjacent rows. Additionally, since

is the first integer in the Young tableau

T that differs from

S, there are no integers lying above

. Hence, the condition (1) implies that

M must be in the first row. According to Condition (3)

in the second row, there must be exactly

boxes to the left of

boxes. Condition (2) implies that

hence

M can only be at the end of the first row in

Z. This means that the first row of

T is

, namely, the first row of

T is exactly the same as the first row of

Z.

We proceed by using induction on the number of rows to prove that, when the first row of T is the same as that of Z, T can be moved to a lexicographically smaller tableau through an EH group action. If , then the Young diagram has only two rows. The first row of T is identical to that of Z, so there is only one way to fill the second row, which implies T is the same as Z. However, this contradicts the assumption that . Therefore, this case cannot occur when .

If , by the induction hypothesis, for Young diagrams with s rows satisfying the conditions, the action of the EH group on all of its Young tableaux is doubly transitive. Let be the sub-Young diagram of obtained by removing the first row. Similarly, let and be the Young tableaux obtained by removing the first row from T and Z, respectively. Then the has s rows and , are Young tableaux of satisfying the conditions.

We can identify actions

on the set of Young tableaux of

with actions

on the tableaux of

that have the same first row as

Z, since actions

do not change the integers

in the first row. If

is not the lexicographically smallest Young tableau of diagram

, then by the induction hypothesis, there exists an EH group action

such that

in the lexicographic order and consequently,

. If

is the lexicographically smallest Young tableau of

, then since

,

must be in the same column as

and directly below

. Now, we first exchange

M with

in

T using

, which simultaneously changes

Z. Next, we apply

to exchange

and

in

. Since the distance between

and

in

is

, no changes occur in

. Finally, we exchange

M with

in

using

, resulting in

Because

and

M in

are in the same column, they remain unchanged. Thus,

fixes

Z and reduces

to

M in

T, hence

Therefore, the claim is proved according to the induction hypothesis. Also note that this induction depends on proving other cases of the lemma, but other cases do not need induction, thus avoiding circular reasoning.

Subcase 5.2: If , that is and are in different columns, then we consider the position of .

Subcase 5.2.1: If

, then

, hence there is no integer above

M. If

M is not in the first row, then by Assumption (1),

which is a contradiction. Therefore,

is the first row of

T. This means that the first row of

T is exactly the same as the first row of

Z. We have already addressed such a case in Case 5.1, so we are done.

Subcase 5.2.2: If , Let . Similarly, the possible positions for are as follows:

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

.

We can sequentially exchange adjacent pairs of to move to the original position of in T. This reduces to Cases 1, 2, or 3, which have been proved earlier. Thus, through a composition of several group actions, we can exchange M with in the tableau T to obtain a Young tableau with a smaller lexicographic order. However, we need to check that Z remains unchanged after these actions.

If , i.e., M is at the end of the first row in Z, then since , the numbers , are also in the first row in Z. Hence, the actions leave Z unchanged. If , the length of the i-th row is at least as long as the row containing M in T. Consequently, , all lie in the same row of Z, keeping Z unchanged. Since M and are in different rows, it follows that . Therefore, we have completed the proof of Case 5.

Combining all the cases above, we are done. □

Using the doubly transitivity of the EH group action, we can establish that the EH group is actually a very large subgroup. Under certain conditions, it is either the alternating group or the full symmetric group. To begin, let us revisit a classical theorem in group theory.

This theorem tells us that we need to find a nontrivial element that moves only a sufficiently small number of elements.

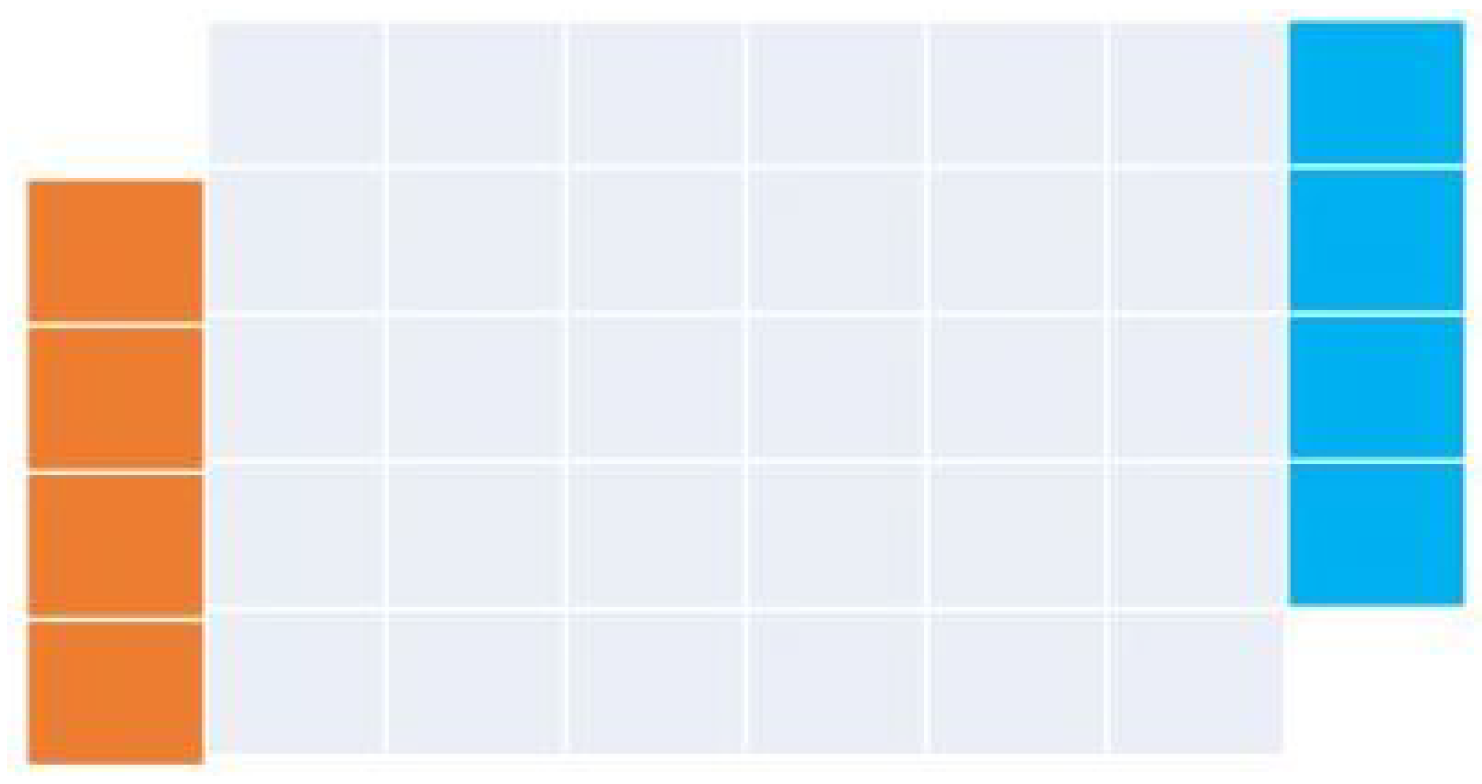

Proof. Let s be the length of the first column of and be the length of the first row. Additionally, let be the distance from the lower-left corner to the upper-right corner of the Young diagram .

If the ramification sequence

satisfies

we consider the EH group element

. Let

A be the set of all Young tableaux moved by

, i.e., those not fixed by

. Let

T be a Young tableau in

A. Since

L is the farthest distance between two boxes in

and

L can only be the distance between the lower-left corner

and the upper-right corner

of

. Thus, the integers in the lower-left box or the upper-right box must be

. Since the total number of boxes in the first column and row is

and the integers filled in the boxes except the lower-left and upper-right boxes must be less than

, the numbers filled in the first row and column are exactly

. Now, consider

and

. Since

is the smallest integer after removing the first row and first column, we have

. Similarly,

is the second smallest integer after removing the first row and first column, so either

or

.

We construct three Young tableaux from T. The tableau is obtained by exchanging with , by exchanging with , and by first exchanging with , and then with . Due to the special positions of and , the resulting tableaux are still Young tableaux. Since each of has at least one of and not in the lower-left corner or the upper-right corner, they will all be fixed by .

For any

with

, we can similarly construct the corresponding three tableaux

. Next, we show that

and

are distinct Young tableaux. By construction,

is different from

and

. Moreover, since the lower-left corner and the upper-right corner of

are

, and those of

are

and

, respectively,

is different from

. The tableaux

and

are obtained by the actions

and

on

T and

S, respectively. If

, then the distances between

and

in

and

are different, so

. If

, then

. Since

, we have

Therefore,

is different from

. Similarly, by symmetry,

is distinct from

and

is distinct from

as well.

and

are obtained from

and

, respectively, by exchanging

with

. If the positions of

and

are different, then

. If the positions of

in

and

are the same, then the positions of

and

would be completely identical, contradicting the distinctness of

and

. Hence,

and

must be distinct. Therefore,

are mutually distinct Young tableaux.

By constructing for each T in A, we obtain a new set of Young tableaux. Similarly, sets can be obtained. As argued earlier, the sets have equal cardinality and are pairwise disjoint. Therefore, the number of Young tableaux moved by is at most one-quarter of the total number of Young tableaux.

If the ramification sequence

does not satisfy

we then consider the EH group element

. The proof follows a similar approach to the previous case. Let

A be the set of all Young tableaux moved by

. For any

, the lower-left corner and the upper-right corner of

T are

and

. We denote the Young diagram obtained from removing the first row and first column of

as

. If

has only one upper-left corner, it must be in the first row of

. Given that the smallest integer in

is

, the upper-left corner of

must be

, and

must be adjacent to

either to the right or below. Since the upper-left corner is in the first row of

,

cannot be in the same row as

or

.

For T, we construct as follows: is obtained from T by exchanging with , by exchanging with , and by first exchanging with and then with . The resulting tableaux are still Young tableaux. By arguments analogous to those used previously, and are pairwise distinct Young tableaux. Therefore, similarly, we can conclude that the number of Young tableaux moved by is at most one-quarter of all Young tableaux.

If has more than one upper-left corner, we choose any two of them, denoted as and . For any , we construct corresponding tableaux as follows: is obtained from exchanging with , by exchanging with , and by exchanging with . Since both and are upper-left corners, the resulting tableaux remain Young tableaux after these exchanges. Moreover, the tableaux are fixed by the EH group element . Finally, using similar reasoning, we conclude that the number of Young tableaux moved by is at most one-quarter of all Young tableaux. □