Fracture Evolution in Rocks with a Hole and Symmetric Edge Cracks Under Biaxial Compression: An Experimental and Numerical Study

Abstract

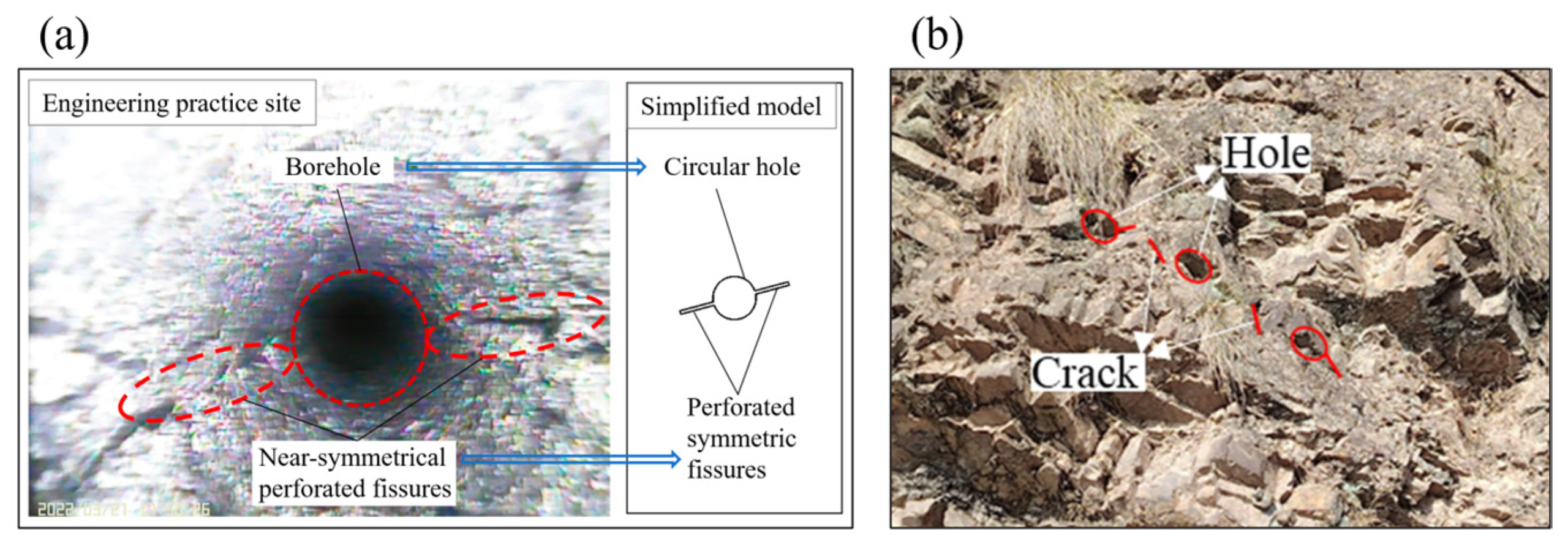

1. Introduction

2. Methods

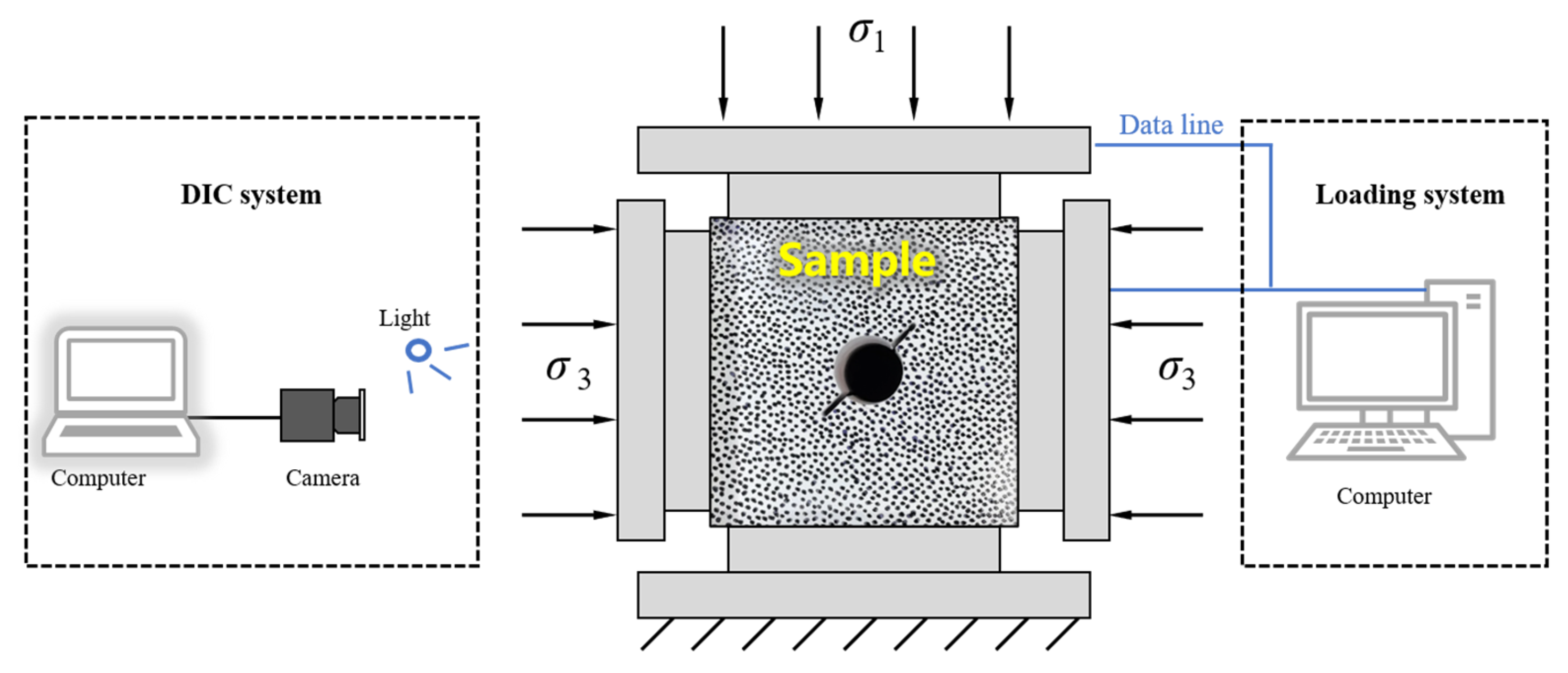

2.1. Experimental Method

2.1.1. Sample Features and Naming Conventions

2.1.2. Experimental System and Procedure

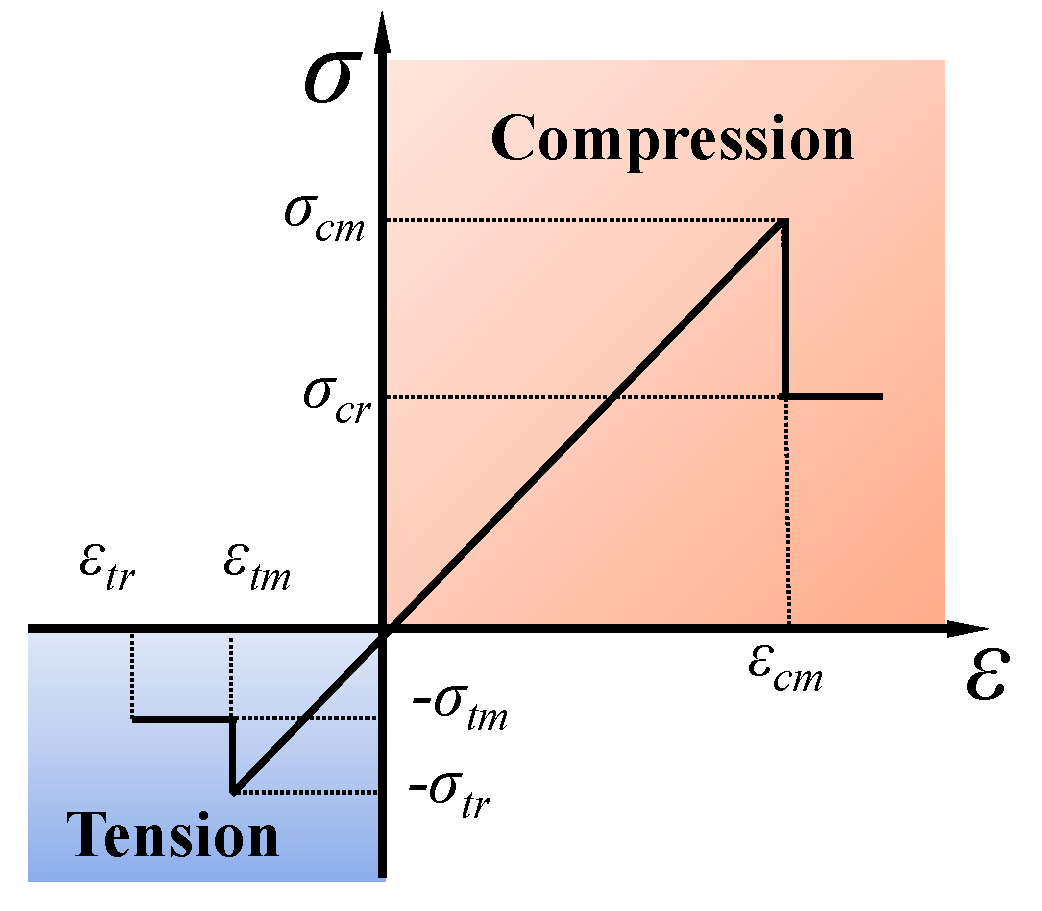

2.2. Numerical Method

2.2.1. Introduction to RFPA Numerical Method

2.2.2. Modeling Process and Numerical Simulation Parameters

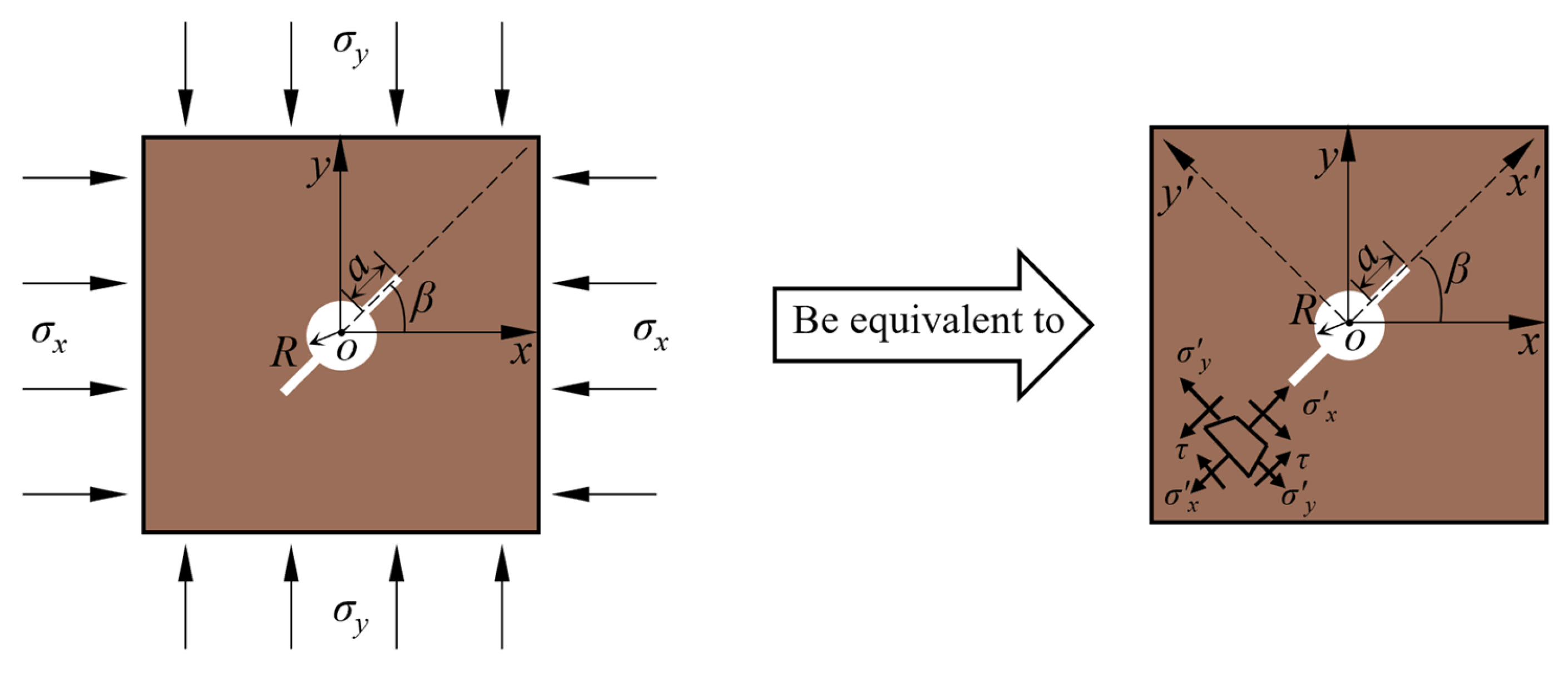

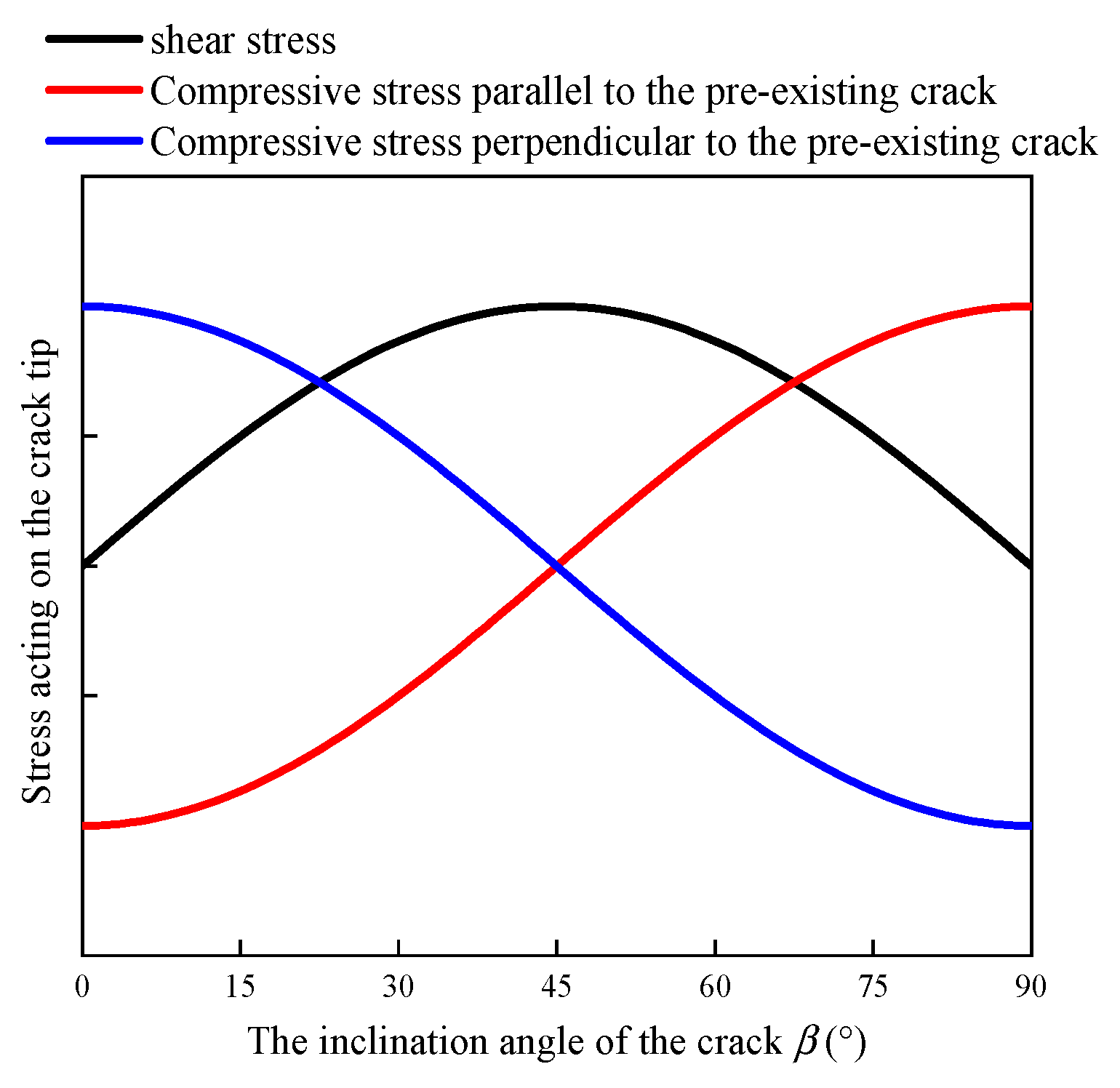

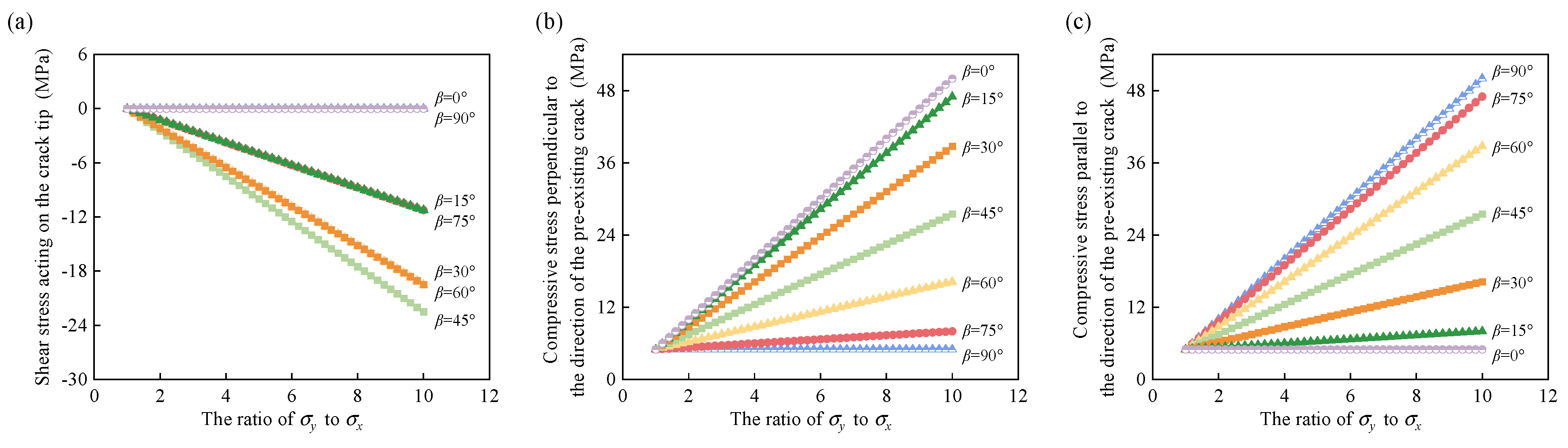

3. Stress Intensity Factors for Symmetrical Inclined Double Cracks at the Circular Hole Edge Under Biaxial Compression

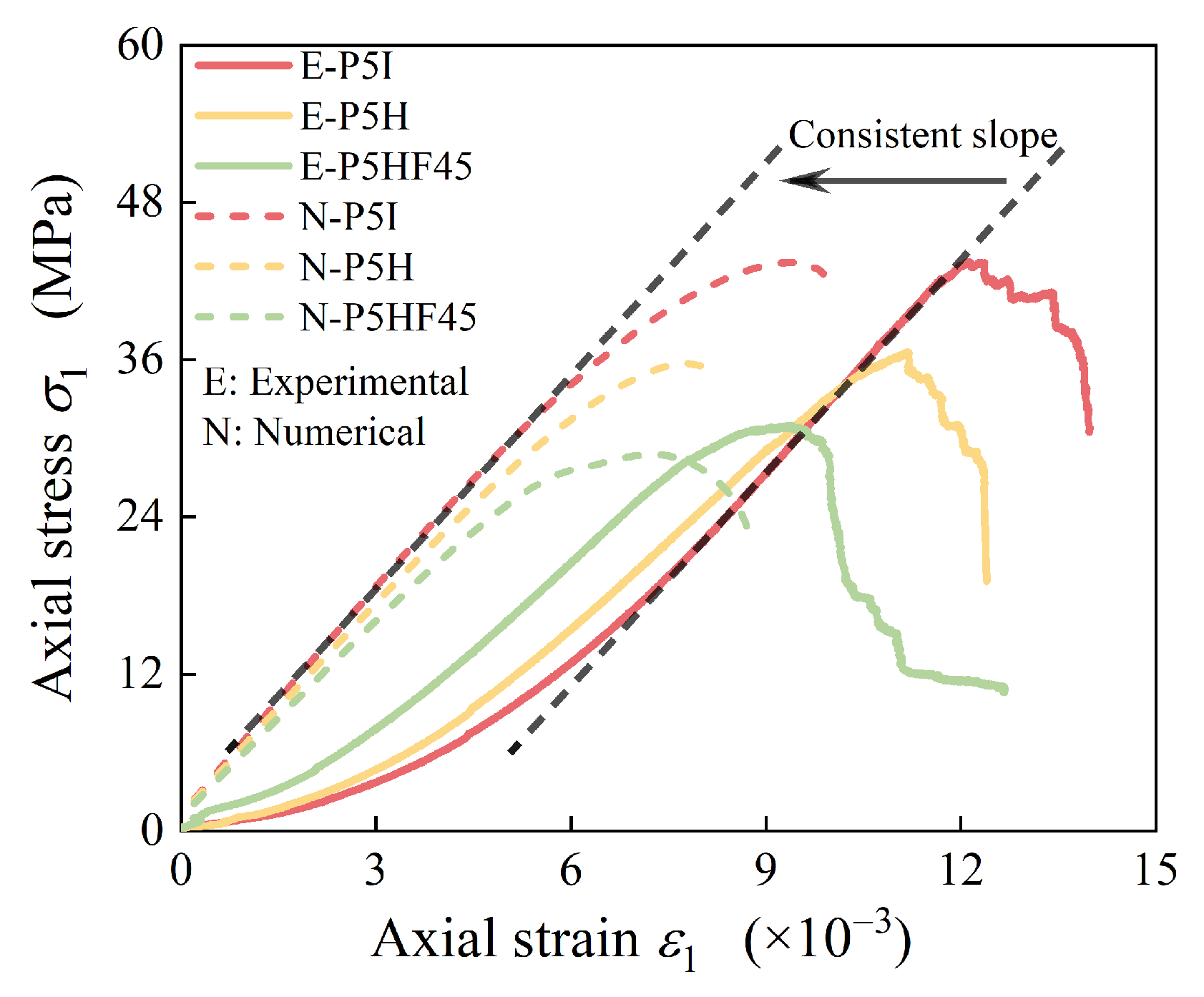

4. Mechanical Properties of Combined Defect Specimens

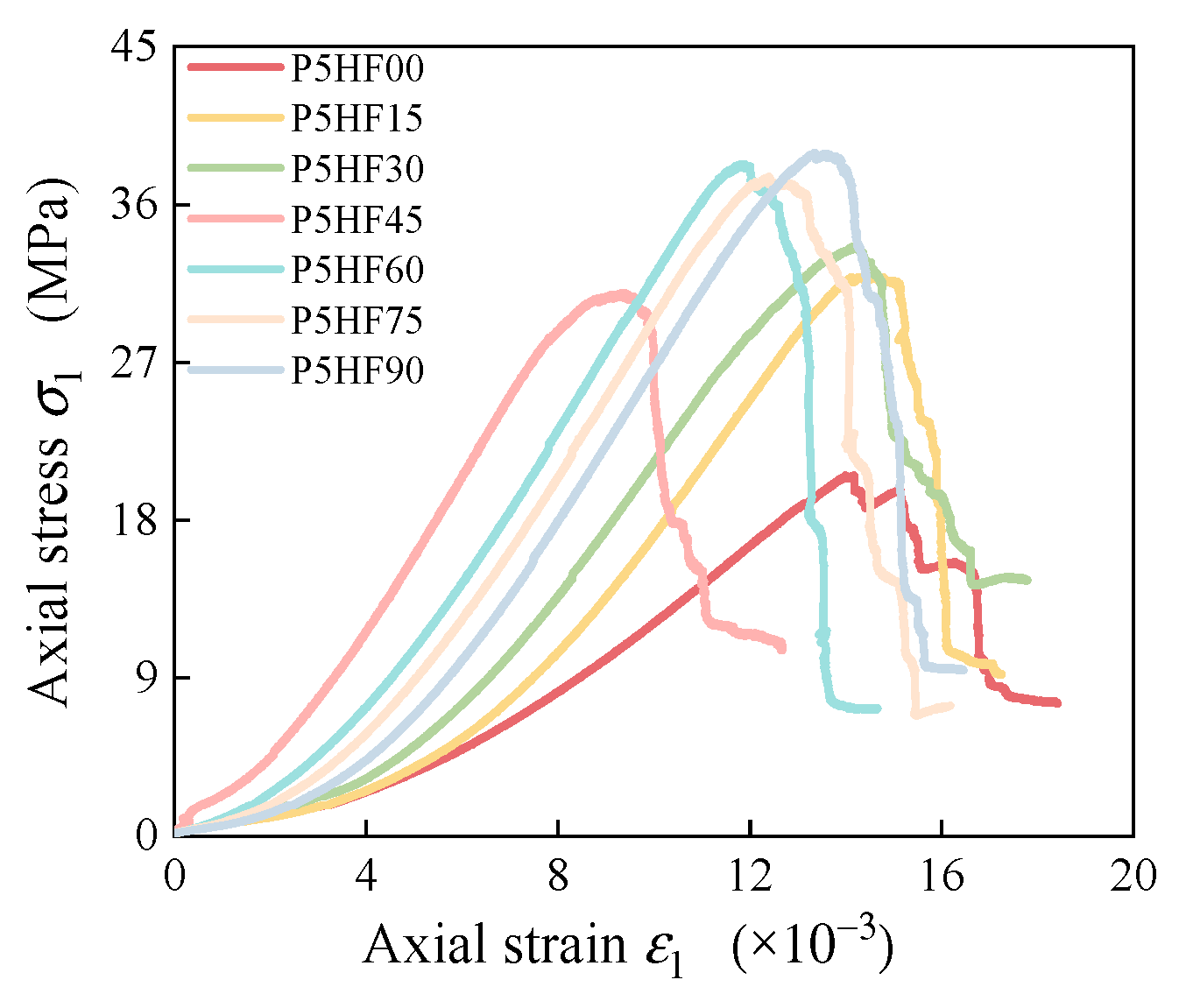

4.1. Stress–Strain Curve and Peak Stress

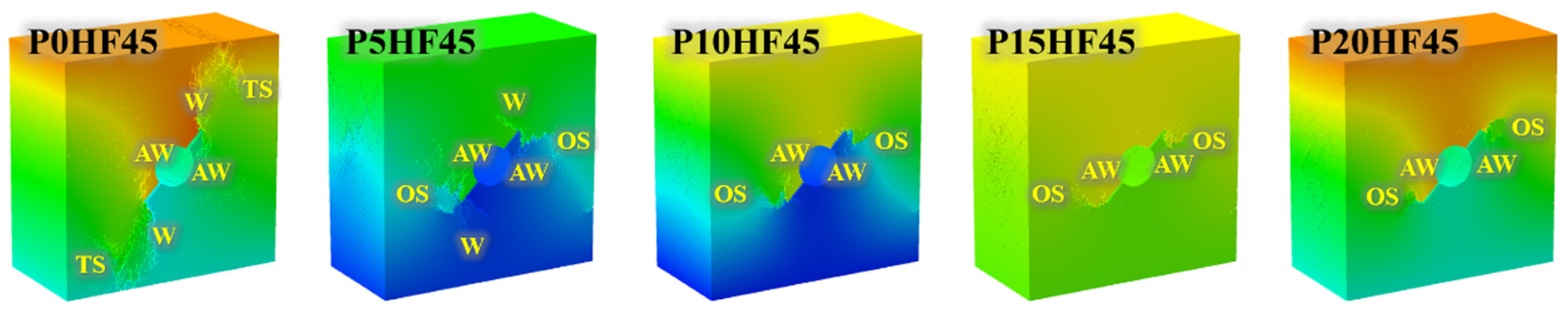

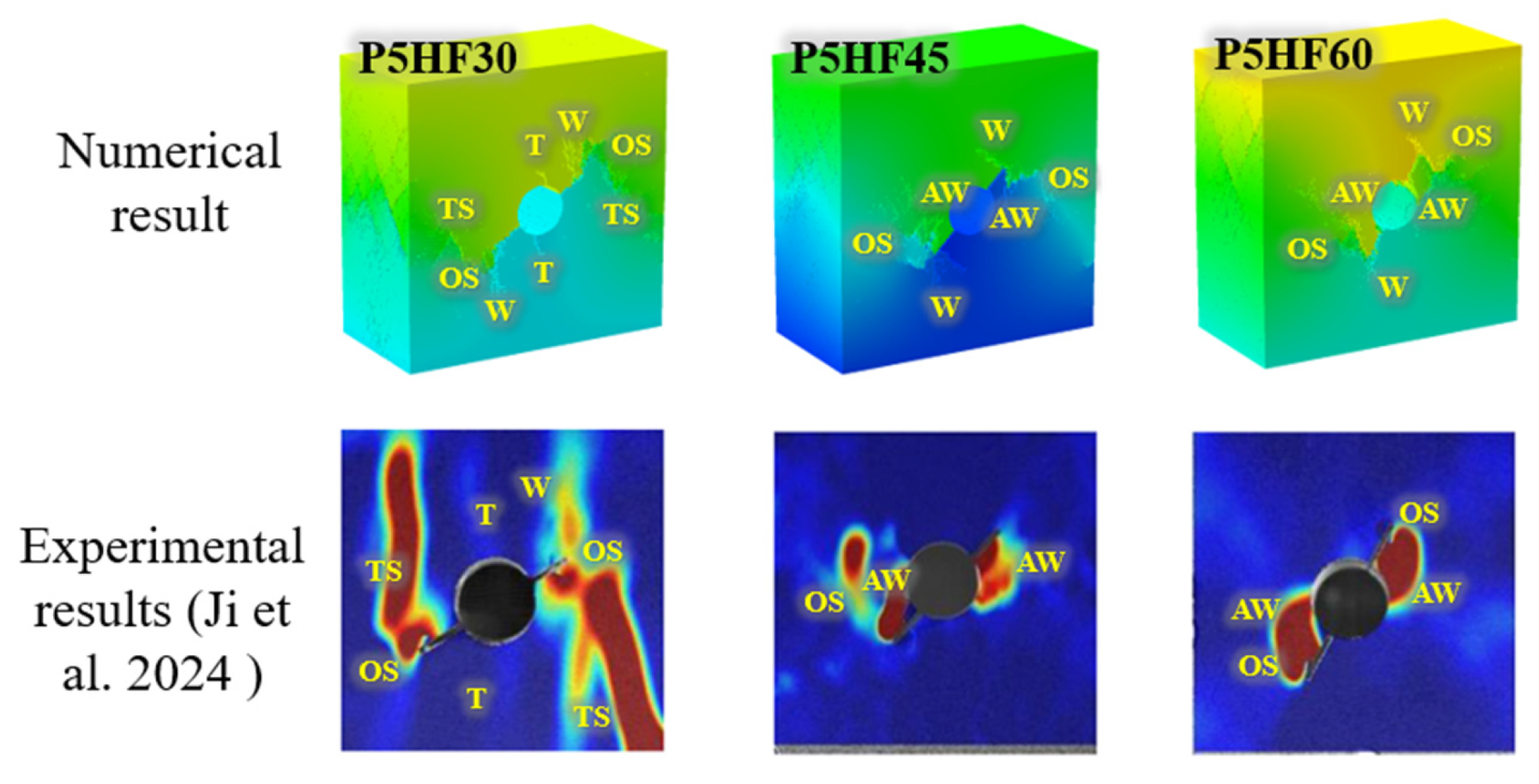

4.2. Fracture Morphology

5. Characteristics of Crack Initiation and Propagation

5.1. Crack Initiation Site

5.2. Crack Propagation

6. Discussion

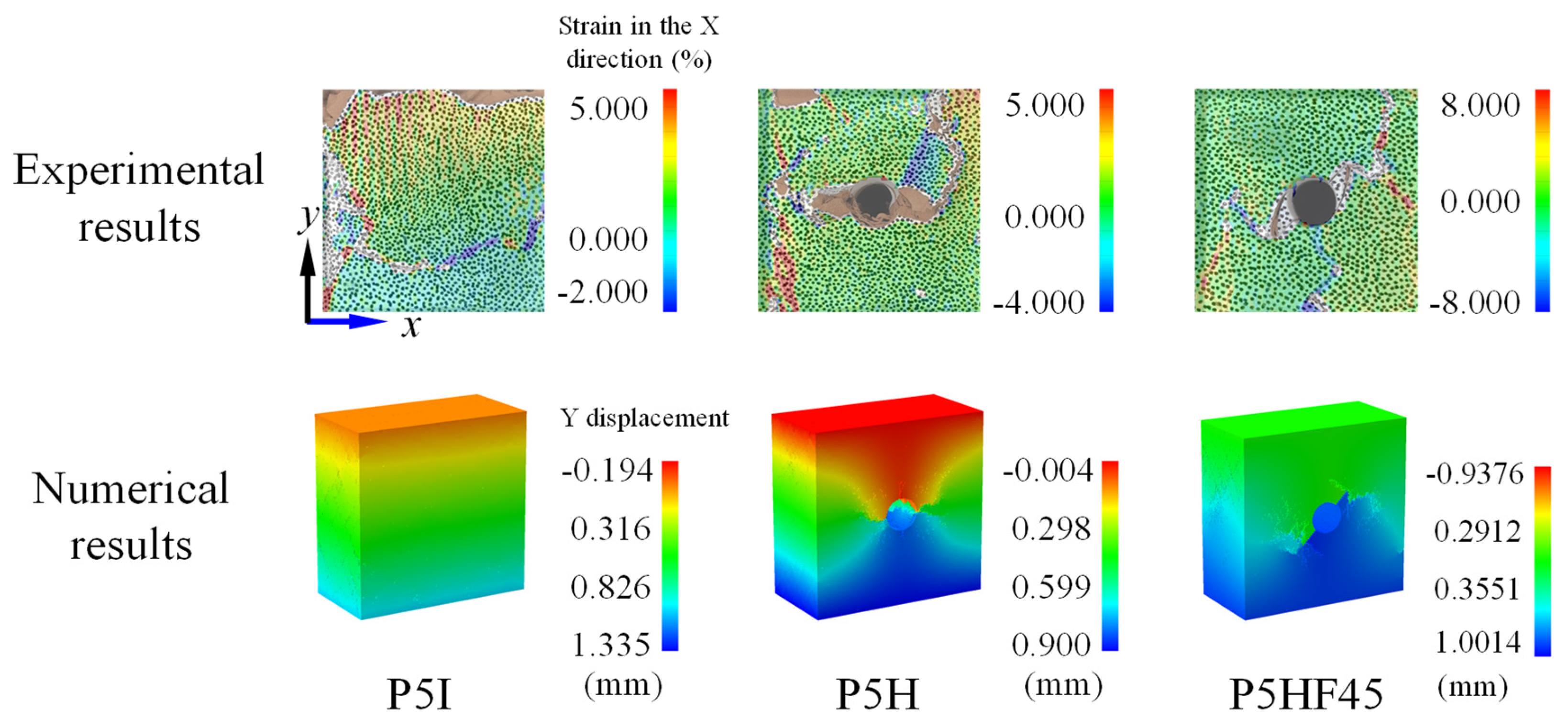

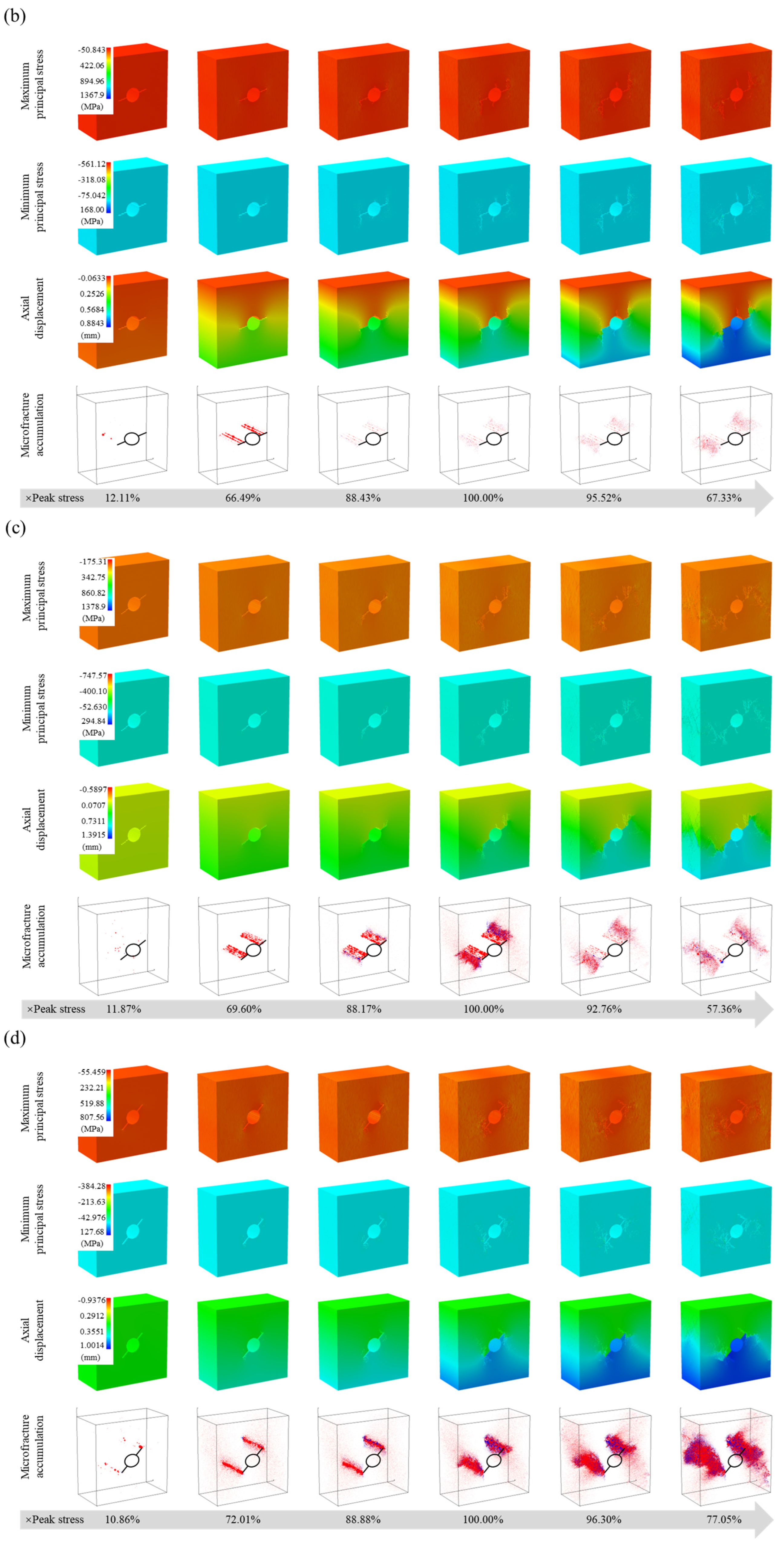

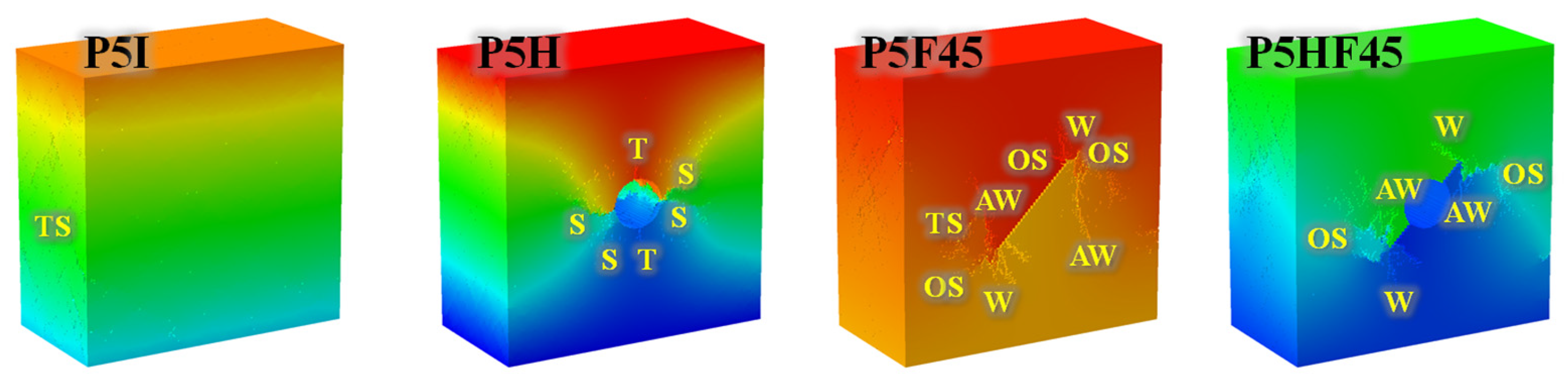

6.1. Implications of the 3D Simulation for Understanding the Fracture Process

6.2. Comparative Analysis of Fracture Morphologies Between Combined and Single Defects

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Increasing the crack inclination angle β induces nonlinear increases in both specimen peak stress and strain, while the elastic modulus shows a trend of initially slightly decreasing followed by gradually increasing. When β is 60°, 75°, and 90°, the elastic modulus is nearly consistent. When β is 75° and 90°, the strain at peak stress increases a lot. As the lateral pressure increases, there is a nonlinear trend of increasing peak stress of composite defect samples containing 45° inclined cracks, with relatively minor changes in both the elastic modulus and strain at peak stress.

- (2)

- When β = 0°, 15°, and 30°, the formation of the failure mode is dominated by oblique secondary cracks emanating from crack defect tips and far-field tensile–shear cracks, resulting in a tensile–shear failure pattern. The initial crack is characterized by wing cracks or anti-wing cracks at the crack defect tips, followed by tensile cracks formed below and above the hole. When β = 45° and 60°, the failure mode is similarly dominated by oblique secondary cracks from the crack defect tips, also exhibiting a tensile–shear failure pattern. The initial cracks are also wing cracks or anti-wing cracks at the crack defect tips, followed by oblique secondary cracks that emanate from these tips. When β = 75° and 90°, the final failure mode transitions to shear failure, primarily controlled by shear cracks along the hole walls. The initial cracks are shear cracks at the hole walls.

- (3)

- As the lateral pressure changes, the crack initiation site for the combined defect sample with 45° inclined cracks is consistently at the crack defect tips. Meanwhile, there is a more pronounced tendency of the specimens to expand laterally. Moreover, under high lateral pressures (15 and 20 MPa), wing cracks do not appear. This is because at excessively high lateral pressures, the combined defect samples with a 45° inclination angle exhibit central symmetry, which often leads to a change in the maximum principal stress direction, and cracks propagate parallel to this direction, driving anti-wing cracks toward specimen boundaries.

- (4)

- The three-dimensional numerical simulation realistically represents the overall fracture behavior of the specimens. Engineering practice necessitates rigorous through-crack propagation surveillance adjacent to hole-type defects, particularly under crack orientations deviating significantly from the maximum principal stress direction (>45°). When assessing tunnel stability, it is necessary to go beyond mere surface displacement monitoring and to fully consider the risks associated with the propagation of concealed internal fractures. Consequently, this necessitates the development of more effective support schemes, such as targeted reinforcement of potential internal separations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Z.Y.; Zuo, J.P.; Zhu, F.; Liu, H.Y.; Xu, C.Y. Non-orthogonal Failure Behavior of Roadway Surrounding Rock Subjected to Deep Complicated Stress. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 6261–6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, L.; Liao, J.; Wang, X.; Tan, T.; Chang, L.; Luo, S.; Wang, M. Mechanical characteristics of single cracked limestone in compression-shear fracture under hydro-mechanical coupling. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 119, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Ma, Z. Asymmetric deformation and failure behavior of roadway subjected to different principal stress based on biaxial tests. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 155, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadian, Z.; Sharafisafa, M.; Tahmasebinia, F.; Shen, L.M. Experimental and numerical investigations on crack development in 3D printed rock-like specimens with pre-existing flaws. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 241, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.H.; Liang, Y.P.; Staat, M.; Li, Q.G.; Li, J.B. Discontinuous fracture behaviors and constitutive model of sandstone specimens containing non-parallel prefabricated fissures under uniaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 131, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Jiang, Q.; Lu, P.; Xie, P.; Duan, S.S. Laboratory investigation on the failure characteristics of rock-like materials with fully closed non-persistent joints. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 122, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y. Energy Dissipation of Rock with Different Parallel Flaw Inclinations under Dynamic and Static Combined Loading. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.P.; Yang, S.Q. A numerical study of acoustic emission characteristics of sandstone specimen containing a hole-like flaw under uniaxial compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 242, 107430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.B.; Chen, Y.L.; Yi, W.; Guo, S.C. Investigation on crack evolution behaviors and mechanism on rock-like specimen with two circular-holes under compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 118, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Shi, P.; Wan, Z.; Xiong, L.; Fan, B.; Zhen, Z. Numerical Analysis of Perforated Symmetric Fissures on Mechanical Properties of Hole-Containing Sandstone. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Liu, K.; Ge, D.; Han, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S. Fracture Behavior and Cracking Mechanism of Rock Materials Containing Fissure-Holes Under Brazilian Splitting Tests. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Q.; Huang, Y.H.; Tian, W.L.; Zhu, J.B. An experimental investigation on strength, deformation and crack evolution behavior of sandstone containing two oval flaws under uniaxial compression. Eng. Geol. 2017, 217, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, H.D.; Liu, H.N.; Xia, Z.G.; Zhao, Y.W.; Zhai, J.Y. Numerical simulation of mesomechanical properties of limestone containing dissolved hole and persistent joint. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 122, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Jiang, Y.J.; Luan, H.J.; Du, Y.T.; Zhu, Y.G.; Liu, J.K. Numerical investigation on the shear behavior of rock-like materials containing fissure-holes with FEM-CZM method. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 125, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, H.; Lin, H.; Zhao, Y.L.; Liu, Y. Fracture behaviour of central-flawed rock plate under uniaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2020, 106, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.H.C.; Lin, P. Numerical study of stress distribution and crack coalescence mechanisms of a solid containing multiple holes. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 79, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.A. Numerical Simulation of Progressive Rock Failure and Associated Seismicity. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1997, 34, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.A.; Wong, R.H.C.; Chau, K.T.; Lin, P. Modeling of compression-induced splitting failure in heterogeneous brittle porous solids. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2005, 72, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Sloan, S.W.; Sheng, D.C.; Tang, C.A. Numerical analysis of the failure process around a circular opening in rock. Comput. Geotech. 2012, 39, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.H.C.; Lin, P.; Tang, C.A. Experimental and numerical study on splitting failure of brittle solids containing single pore under uniaxial compression. Mech. Mater. 2006, 38, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.C.; Liu, J.; Tang, C.A.; Zhao, X.D.; Brady, B.H. Simulation of progressive fracturing processes around underground excavations under biaxial compression. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2005, 20, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Tang, C.a.; Cheng, L.; Duan, W.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q. Fracture process of a simplified laboratory model for a cross-fault tunnel with rigid reinforcement rings: Experimental and numerical insights. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 157, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Wong, R.H.C.; Tang, C.A. Experimental study of coalescence mechanisms and failure under uniaxial compression of granite containing multiple holes. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 77, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.X.; Viegas, G.; Zhang, Q.B. Mechanical and fracturing characteristics of defected rock-like materials under biaxial compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 176, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.A.; Tang, S.B.; Gong, B.; Bai, H.M. Discontinuous deformation and displacement analysis: From continuous to discontinuous. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2015, 58, 1567–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.A.; Webb, A.A.G.; Moore, W.B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Ma, T.H.; Chen, T.T. Breaking Earth’s shell into a global plate network. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.Q.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, Q. A new method to model the non-linear crack closure behavior of rocks under uniaxial compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 112, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.; Martin, C.D.; Sego, D.C. A clumped particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2007, 44, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, O.L. Analysis of an infinite plate containing radial cracks originating at the boundary of an internal circular hole. J. Math. Phys. 1956, 35, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.C. The infinite sheet with cracked cylindrical hole under inclined tension or in-plane shear. Int. J. Fract. 1975, 11, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Yang, S.Q.; Tian, W.L. Cracking process of a granite specimen that contains multiple pre-existing holes under uniaxial compression. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2019, 42, 1341–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ee (MPa) | 6800 | σe (MPa) | 110 | v | 0.25 |

| me | 3 | mu | 3 | φ (°) | 35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Zeng, L.; Guo, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, A. Fracture Evolution in Rocks with a Hole and Symmetric Edge Cracks Under Biaxial Compression: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Mathematics 2025, 13, 4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244035

Zhang D, Zeng L, Guo S, Chen Z, Zhang J, Jiang X, Zhang F, Jiang A. Fracture Evolution in Rocks with a Hole and Symmetric Edge Cracks Under Biaxial Compression: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244035

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Daobing, Linhai Zeng, Shurong Guo, Zhiping Chen, Jiahua Zhang, Xianyong Jiang, Futian Zhang, and Anmin Jiang. 2025. "Fracture Evolution in Rocks with a Hole and Symmetric Edge Cracks Under Biaxial Compression: An Experimental and Numerical Study" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244035

APA StyleZhang, D., Zeng, L., Guo, S., Chen, Z., Zhang, J., Jiang, X., Zhang, F., & Jiang, A. (2025). Fracture Evolution in Rocks with a Hole and Symmetric Edge Cracks Under Biaxial Compression: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Mathematics, 13(24), 4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244035