1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the exponential growth of industrialisation and modernisation has introduced a range of environmental and societal challenges, including an increase in pollution levels, depletion of natural resources, urban overpopulation, and the progressive desertification of rural regions. Among these, air pollution has emerged as a primary concern, increasing attention from international regulatory and public health organisations due to its impact on human health and environmental sustainability. Recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a significant environmental health risk, air pollution contributes to approximately 7 million premature deaths annually worldwide [

1].

Noorimotlagh et al. [

2] define air pollution as the presence of a mixture of several types of substances, including: (i) gases such as carbon monoxide (CO), ground-level ozone (O

3), nitrogen oxides—NO

x = NO + NO

2—and sulfur oxides (SOx), among others; (ii) solids such as particulate matter (PM) with different aerodynamic diameters, especially coarse particles (PM10), fine particles (PM2.5), ultrafine particles (PM1), and nanoparticles (PM0.1); (iii) volatile metals such as zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and lead (Pb); and (iv) volatile organic compounds (VOC), such as bioaerosols and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). In general, air pollutants comprise a broad range of substances, including greenhouse gases (GHGs), particulate matter and ozone.

The transport sector is the second-largest contributor to GHGs emissions in Europe, following the energy sector, with road transport accounting for about 20% of total emissions [

3]. Among transport-related emissions, nitrogen oxides are particularly critical due to their adverse environmental and health effects. NOx compounds are predominantly emitted from anthropogenic combustion sources, notably transportation (46%), agriculture (20%), power generation (10%), industry and residential heating (each contributing approximately 5%) [

4,

5]. NOx emissions are precursors to the formation of ground-level ozone and photochemical smog and are associated with acidification of soil and water bodies, contributing to biodiversity loss [

6]. Epidemiological studies have also linked long-term exposure to NOx with increased incidences of cardiovascular diseases, ischemic stroke, chronic respiratory conditions, and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [

2,

7].

In response to the growing evidence on the harmful effects of NOx, regulatory authorities, particularly within the European Union, have introduced increasingly stringent emission standards [

8]. To comply with these regulations, automotive manufacturers have adopted a suite of exhaust aftertreatment technologies, including the Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) system, which has demonstrated NOx removal efficiencies of up to 96% under optimal operating conditions [

9,

10,

11,

12].

The Urea-SCR technology is currently the dominant solution in the automotive market and is based on ammonia-SCR technology [

13]. SCR technology reduces NOx emissions by injecting a reductant, commonly ammonia, into the exhaust stream, where it reacts with NOx in the presence of a catalyst to produce nitrogen and water [

14]. Due to ammonia’s corrosive nature and associated safety risks, direct storage on board vehicles is unfeasible [

15]. Consequently, ammonia is supplied in the form of an aqueous urea solution (AUS32), commercially known as AdBlue

®, a registered trademark of the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA). AdBlue

® comprises 32.5% ± 0.7 (

w/

w) high-purity urea and 67.5% ± 0.7 (

w/

w) deionised water [

16]. This solution suffers thermolysis and hydrolysis when dosed and injected into the diesel exhaust gas (DEG) stream [

14].

AdBlue

® is produced by dissolving solid urea in high-purity deionised water. Given that water constitutes over two-thirds of the final solution, its purity is essential. This is achieved using advanced water treatment methods such as distillation, deionisation, ultrafiltration, or reverse osmosis [

16].

In this industry, there are two main mixing processes for the production of AdBlue

®: the traditional method based on a stirred tank and the in-line production method [

17]. Although the chemical process is identical in both approaches, the in-line production method has become predominant due to its greater versatility.

The traditional method, also known as batch production, involves the discrete mixing of a predetermined amount of urea (NH2CONH2) with a specific volume of deionised water in a stirred tank. The major disadvantages of this method are: (i) the limitation in the volume of solution produced, which cannot exceed the total volume of the mixing tank; and (ii) the requirement for the solvent to be at a high temperature to accelerate dissolution.

The in-line (continuous) production method is a more flexible and scalable approach where raw materials are continuously fed, and product output is only constrained by the availability of inputs and storage capacity. High shear mixers (HSMs) are commonly used to ensure effective and efficient dissolution, even at lower solvent temperatures [

18].

High-shear mixers, also referred to as rotor–stator (RS) mixers, are among the most advanced mixing devices used in applications requiring intense dispersion, emulsification, and deagglomeration [

18]. An HSM typically consists of a high-speed rotor operating at 500–25,000 rpm within proximity (100–3000 µm) to a fixed stator [

19]. This configuration generates intense shear fields and turbulent flows that facilitate fast particle size reduction through mechanisms such as: (i) erosion, when a larger agglomerate is fragmented, leading to a progressive reduction in its size; (ii) rupture, when the large agglomerate is broken into smaller agglomerates, but all of the same size, this process is repeated until the smallest agglomerate size is obtained; and (iii) shattering, when large agglomerates are broken directly into very small pieces, without the existence of a passage through intermediate agglomerate size [

20].

Mixing operations can be carried out either in batch or continuous mode. In batch mixing, the components are introduced into a vessel and agitated for a defined period until the desired degree of homogeneity is achieved. This cyclic operation can result in longer processing times and variability between batches. In contrast, continuous (in-line) mixing is performed under controlled conditions, where streams of raw materials are continuously fed at controlled flow rates and mixed. The mixing efficiency is determined by flow dynamics, mixer geometry and impeller speed [

21]. Continuous mixing offers advantages such as reduced residence time, improved process control, and consistent product quality, making it particularly suitable for large-scale and high-throughput applications [

18,

22]. The devices utilise rotors with tailored geometries to promote shear and turbulence, which are critical for homogenization and deagglomeration. Optimization parameters include rotor speed, number and height of rotor teeth, shear gap, and blade inclination [

18,

23,

24].

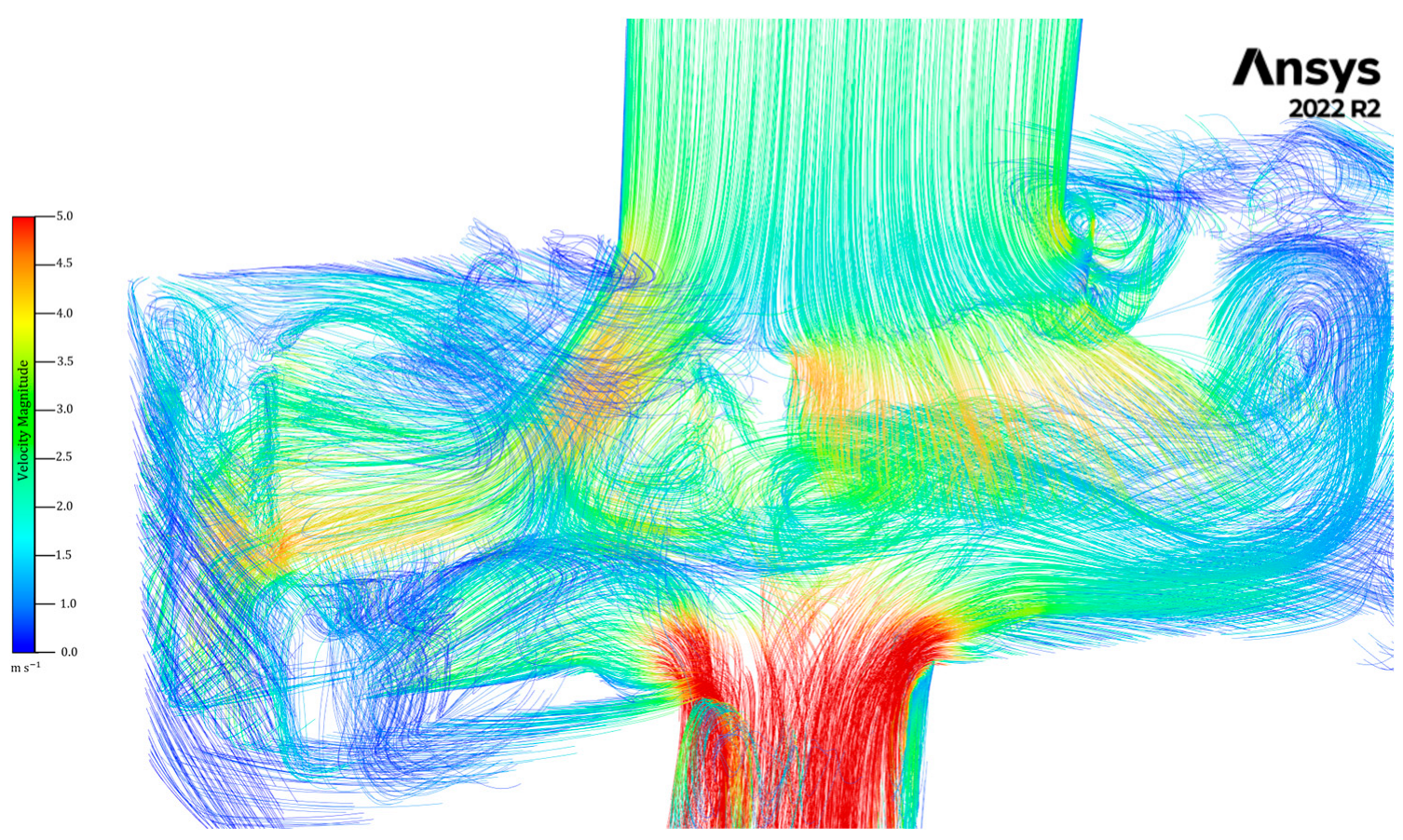

In the analysis of mixing quality reported by Gong et al. [

23], high homogeneity of the final solution is achieved by using high blade/rotor speeds, with the number of blades significantly influencing the kinetics of mixing into granules. In another study by Liu et al. [

24], the performance of the HSM mixer can be increased by increasing the rotor speed, the number and height of the rotor teeth, and reducing the spacing between the rotor and the stator, also known as shear gap. The inclination of the rotor teeth also influences the efficiency of the RS set, and in this study, the use of vertical teeth is recommended. This geometry improves material deagglomeration, given the high turbulent dissipation energy generated in the stator. Ming et al. investigate the effect of stator geometry on the performance of continuous high-shear mixers [

21]. Experiments have shown that slot width, area, and angle affect both flow rate and power consumption. Increasing the slot width improves the flow rate while reducing power consumption, whereas enlarging the slot area raises both the flow rate and energy use.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a valuable tool for studying and optimising the complex flow behaviour within rotor–stator systems. CFD enables the detailed analysis of velocity fields, turbulence structures, and the shear stress distributions that are otherwise difficult to measure experimentally due to the opaque and highly dynamic nature of these systems [

17]. By resolving local flow phenomena, CFD supports the design of more efficient mixer geometries and the refinement of operating parameters, thereby enhancing process performance and sustainability.

Recent advances in turbulence modelling, mesh refinement techniques, and computational resources have improved the predictive accuracy of CFD models applied to HSMs. For instance, the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) and Sliding Mesh (SM) methods, which provide steady-state and transient representations of rotor motion, respectively, have been used to simulate rotor–stator interactions [

25,

26]. The accuracy of these simulations largely depends on the choice of turbulence model. Among the commonly employed models, the

k–

ε,

k–

ω SST, and Reynolds Stress Model (RSM) have demonstrated the ability to predict turbulent energy dissipation and shear stress transport in complex flow domains.

Table 1 presents a comparison of turbulence models used in CFD simulations of HSMs.

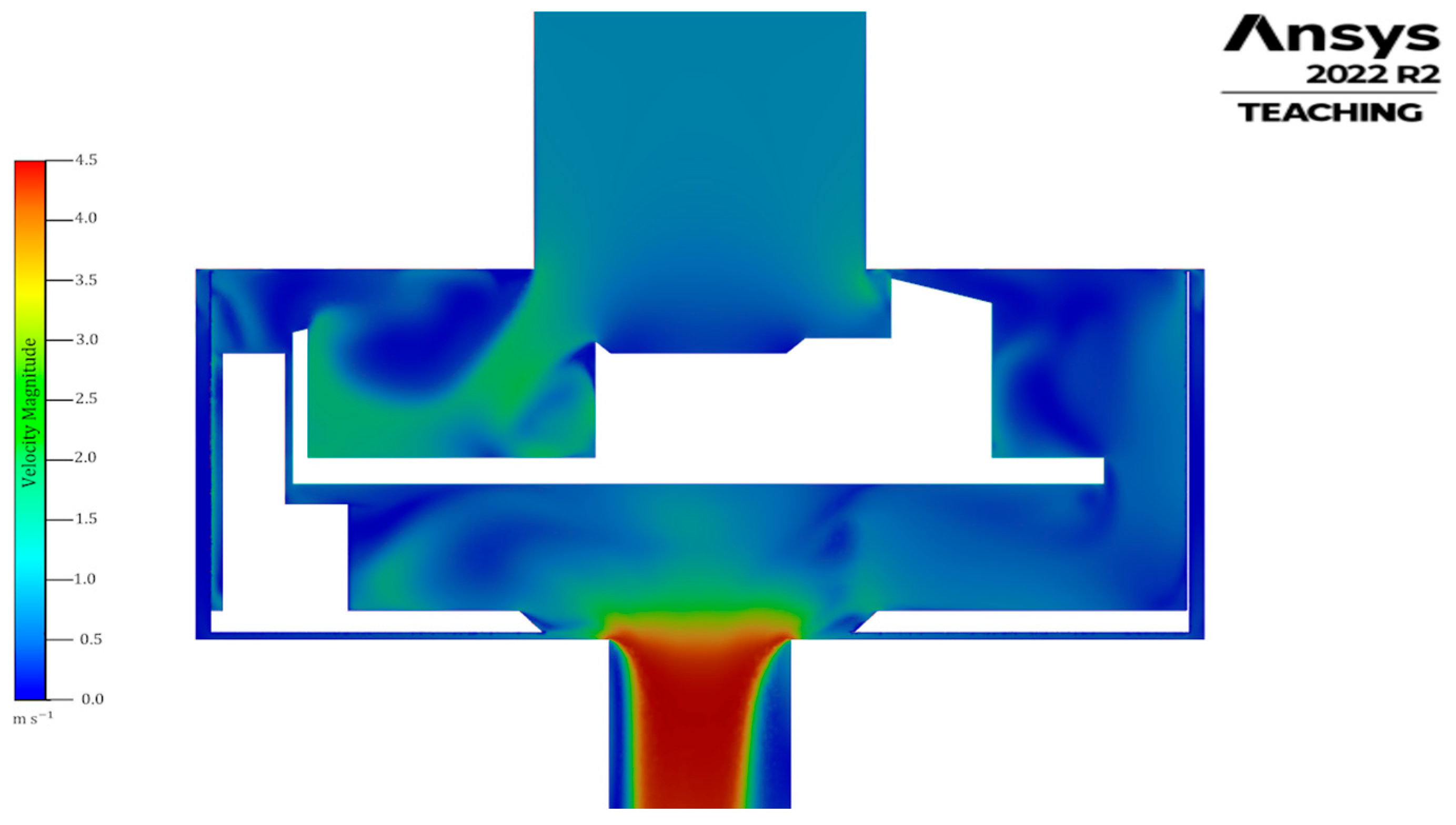

For industrial-scale HSM simulations, the k–ω SST model typically offers the optimal balance between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, particularly in capturing near-wall and interfacial shear regions. The Reynolds Stress Model (RSM) is recommended for detailed validation or design investigations where turbulence anisotropy has a significant impact on mixing behaviour. Meanwhile, standard or RNG k–ε models remain valuable for rapid, process-scale simulations and preliminary design optimisation.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in bridging the gap between laboratory-scale simulations and industrial-scale operations. Scale-up is often hindered by the nonlinear relationship between shear rate, flow regime, and mixing efficiency [

17]. Therefore, validating CFD models with experimental or plant-scale data is essential to ensure that numerical predictions accurately reflect real operational behaviour. In the context of AdBlue

® production, such validation is critical to support process optimisation efforts aimed at reducing thermal energy consumption while maintaining solubility and product quality.

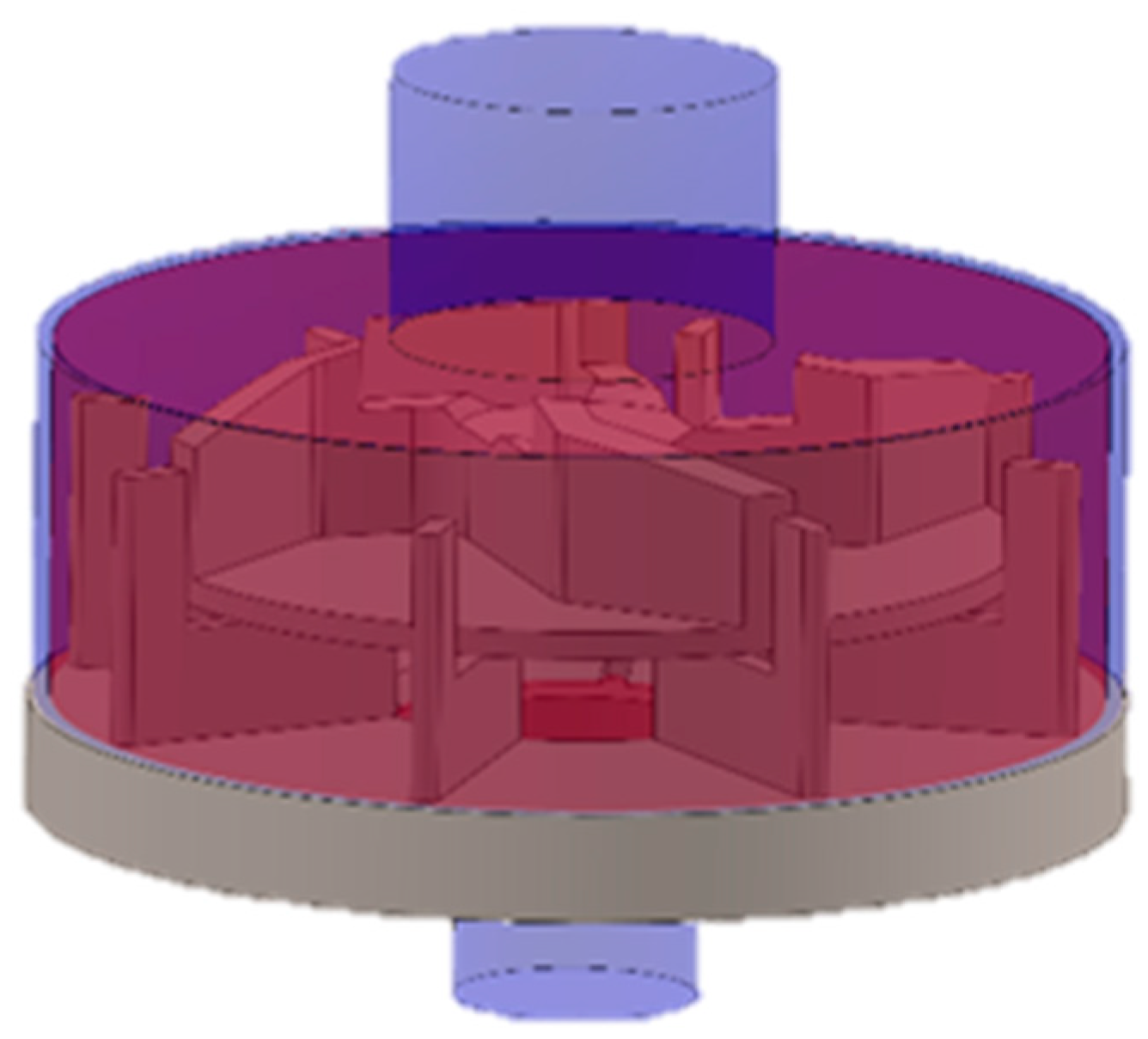

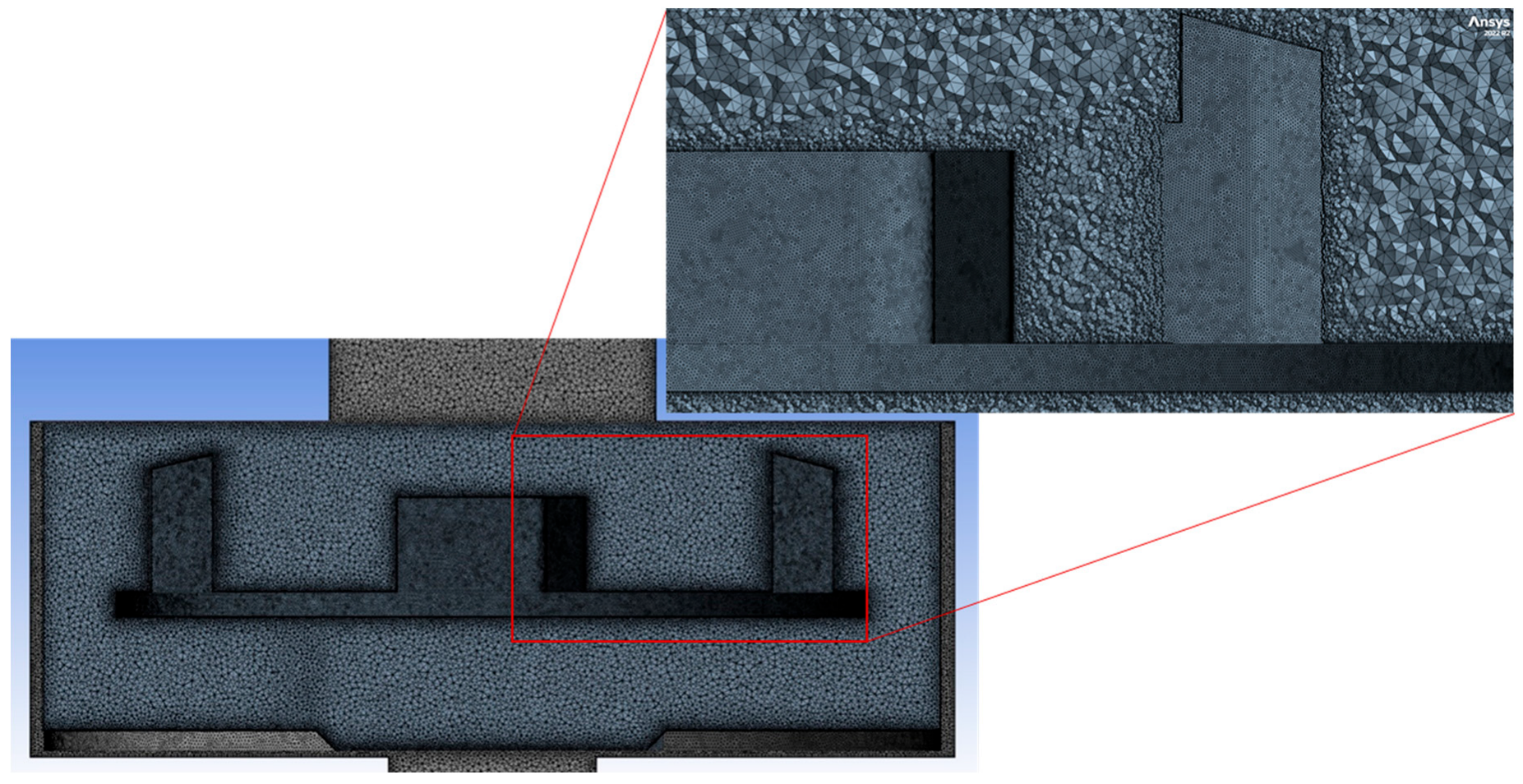

To evaluate and optimize the hydrodynamic performance of the HSM employed in AdBlue® production, a three-phase numerical simulation approach was adopted: (i) Phase I: CFD simulation of the first rotor–stator (RS) assembly; (ii) Phase II: Simulation of the second RS assembly to investigate interactive hydrodynamic effects and (iii) Phase III: In situ measurements of flow, temperature, and mixing variables within the operating HSM used in commercial AdBlue® production.

These simulations provide insights into flow dynamics and mixing homogeneity, which are critical for improving process efficiency and ensuring consistent AdBlue® quality. The CFD models are validated using an industrial case study of AdBlue® production, supporting their application in the design and optimisation of HSM units.