To further analyze the influence of autonomous vehicle control strategies and market penetration rates on the propagation of cascading conflict risk, a series of simulation experiments were conducted using typical microscopic traffic scenarios designed in SUMO.

4.2.2. Result Analysis

- (1)

Computational Complexity Analysis

To evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed framework for real-time intelligent transportation systems, this study analyzes the computational complexity of each component and compares it with existing approaches.

- (a)

Cascading Conflict Identification Complexity

The graph search-based cascading conflict identification algorithm processes conflicts incrementally without pre-constructing the complete conflict graph. The theoretical worst-case complexity is as follows:

where

is the number of initially detected conflicts.

Practical complexity with spatiotemporal pruning is as

where

is the average number of candidate-associated conflicts within the influence window of each conflict. Due to strict spatiotemporal constraints (Equations (8) and (9)),

.

Table 7 summarizes the time complexity, space complexity, and scalability of the proposed method alongside two existing identification approaches.

Statistical analysis of NGSIM data reveals across 1287 detected conflicts. For a typical highway segment monitoring conflicts over 5 min: Rule-based method: comparisons; Our method: comparisons.

- (b)

Mechanism Analysis of Cascading Conflict Risk Propagation

As shown in

Table 8, the four baseline models exhibit varying performance trade-offs between prediction accuracy and computational complexity. Logistic regression, as a linear model, has the lowest model capacity and shortest training time, but its AUC value (0.9753) is significantly inferior to tree-based ensemble methods. Random Forest and XGBoost substantially improve AUC by introducing nonlinear decision boundaries, but this comes at the cost of increased training and inference time due to the use of hundreds of trees. CatBoost achieves the highest AUC (0.9885) while maintaining moderate model size and competitive training time. Its per-sample inference latency meets real-time requirements. Additionally, CatBoost requires the shortest SHAP computation time (20 ms per sample among ensemble models), indicating an optimal balance between model complexity, efficiency, and interpretability.

- (2)

Model Prediction Performance

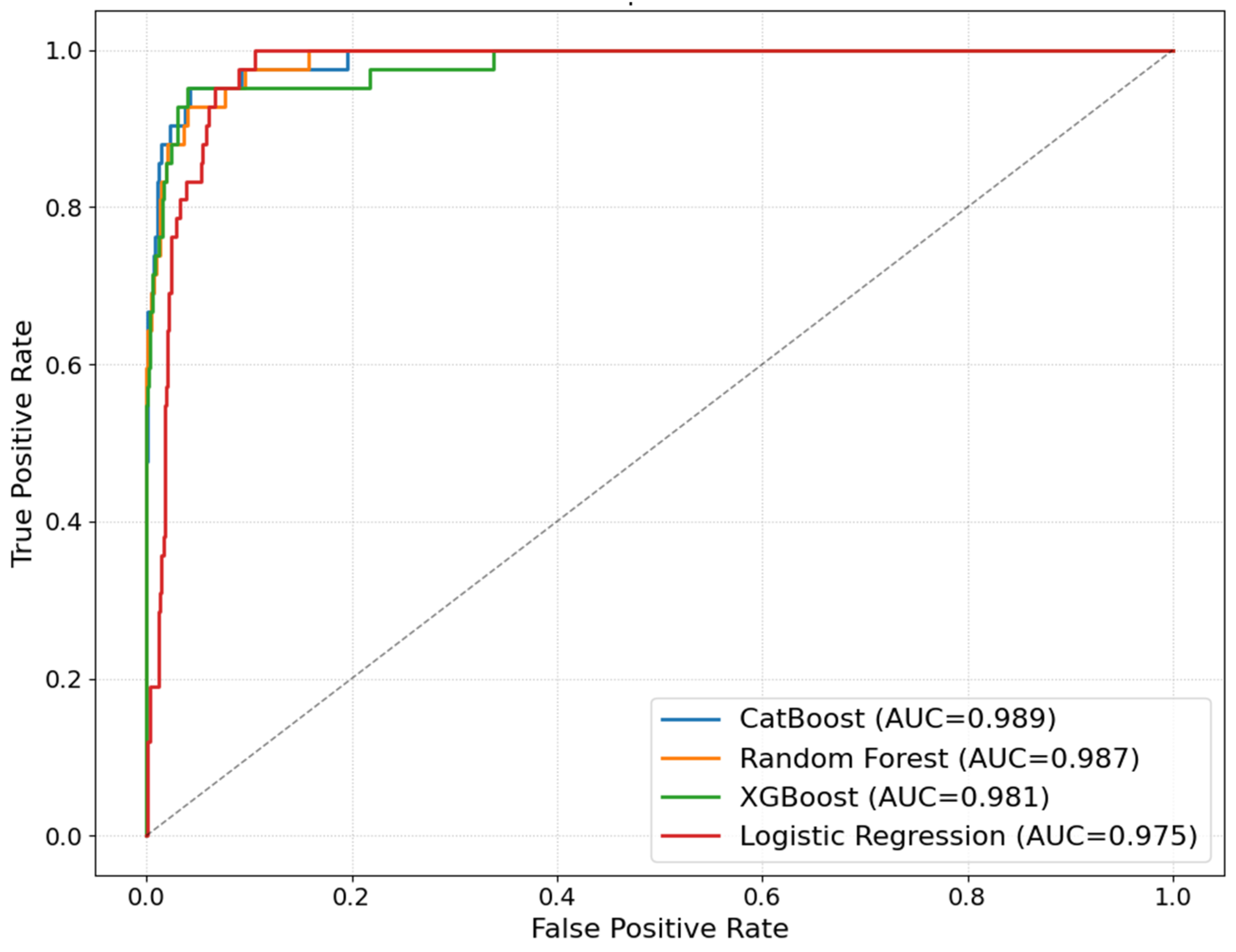

The ROC curves of the four classification models are shown in

Figure 7. The horizontal axis denotes the false positive rate (FPR), and the vertical axis denotes the true positive rate (TPR), while the dashed diagonal line corresponds to a random classifier with AUC = 0.5. The blue, orange, green and red curves represent the CatBoost, Random Forest, XGBoost and logistic regression models, respectively, and the legend reports their AUC values (0.989, 0.987, 0.981 and 0.975). All four curves lie well above the random baseline, indicating strong discriminative power in distinguishing between secondary-conflict and non-secondary-conflict samples. Moreover, the CatBoost curve consistently dominates the others over most FPR ranges and achieves the highest AUC, followed by the two tree-based ensemble models, while logistic regression shows the lowest AUC among the four. This suggests that the nonlinear tree-ensemble models, especially CatBoost, better capture the complex interactions encoded in the constructed feature system and are therefore more suitable as the primary model for subsequent mechanism analysis.

- (3)

Feature Importance Analysis

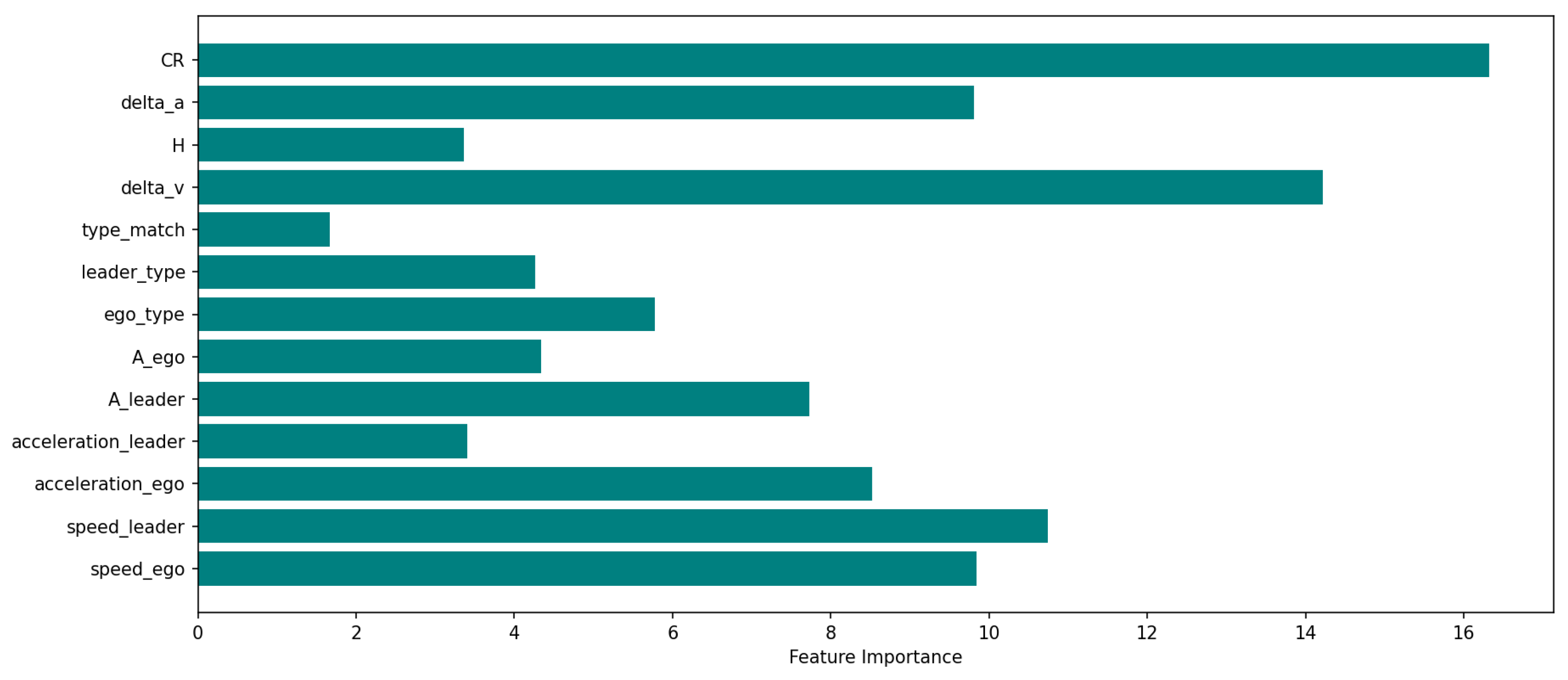

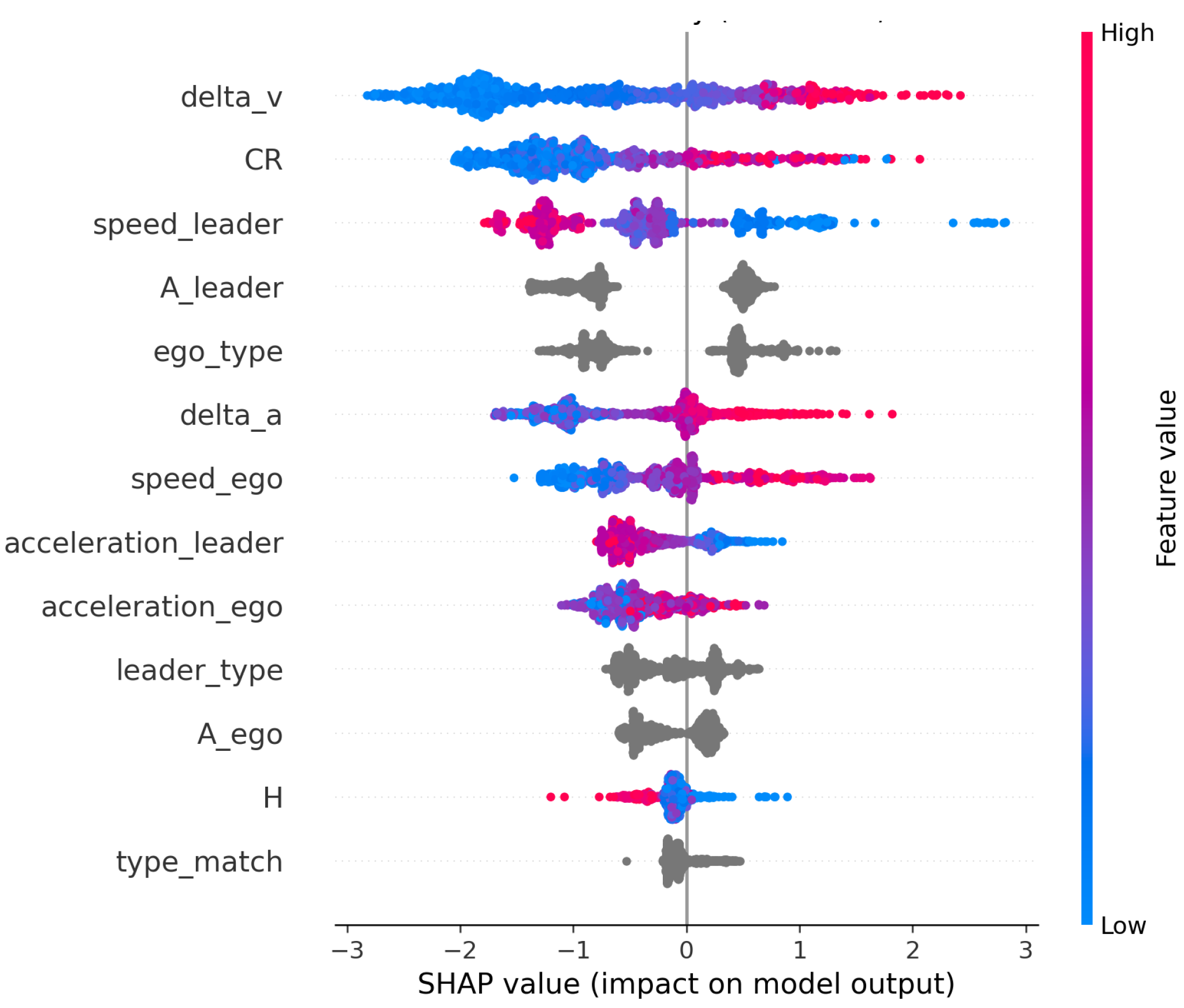

The feature importance ranking (

Figure 8) indicates that dynamic interaction features between vehicles play a central role in driving the model’s predictions. Among them, the primary conflict intensity and the relative speed difference between vehicles exhibit the highest importance. The SHAP summary plot (

Figure 9) further reveals that larger values of speed difference and conflict intensity substantially increase the likelihood of secondary conflict occurrence. The meanings and units of each parameter are shown in

Table 9.

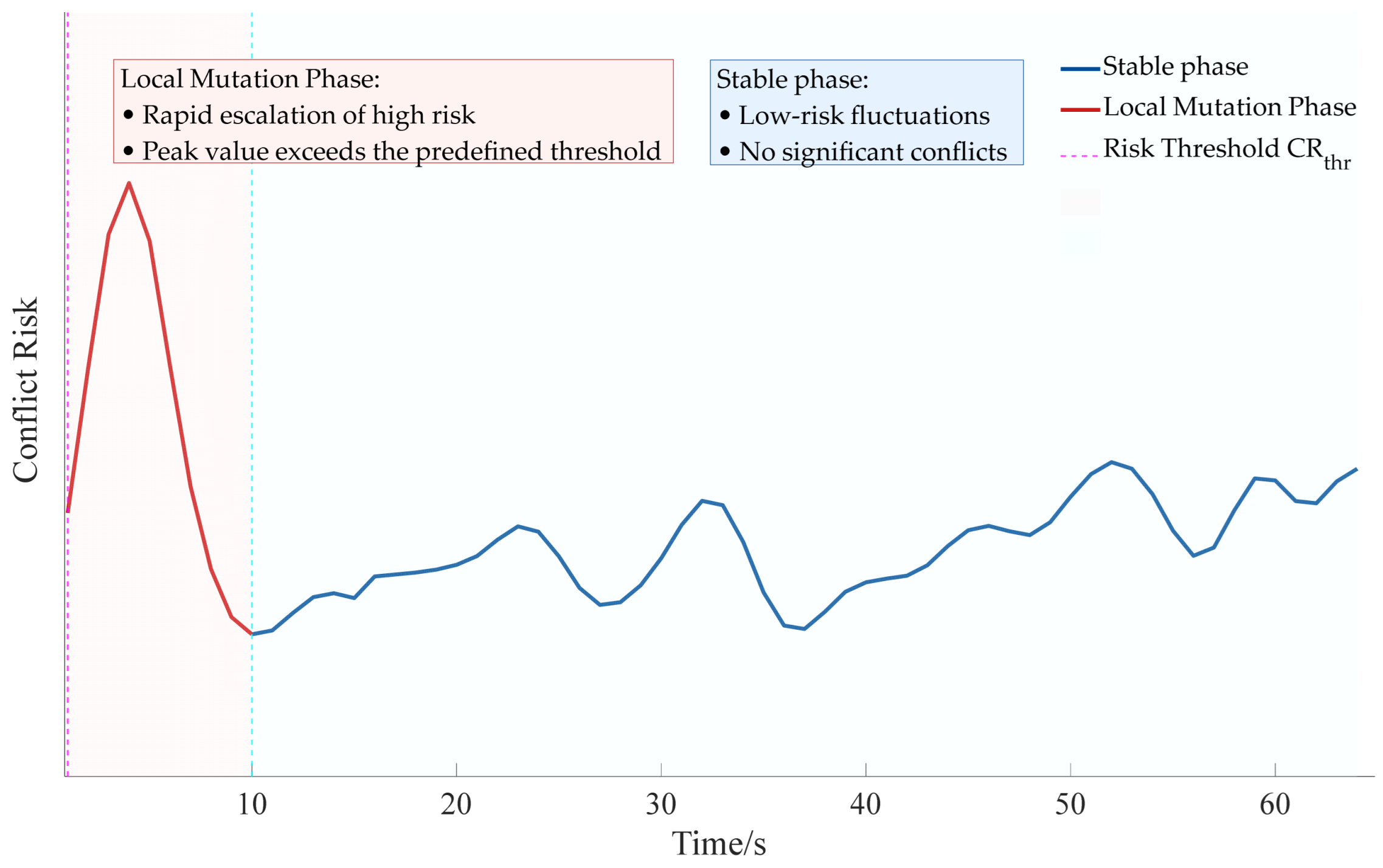

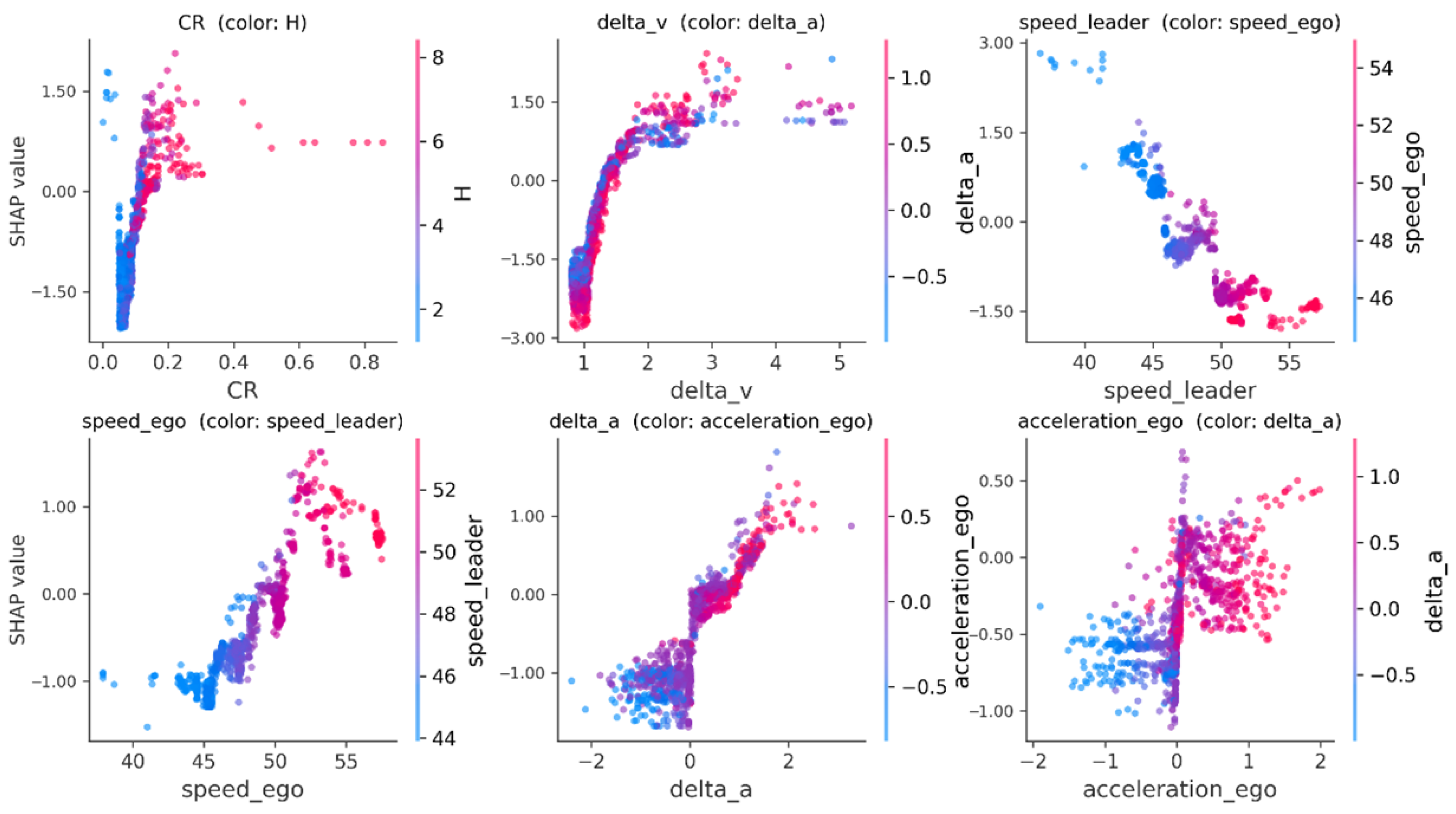

As can be seen from

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, cascading conflict risk exhibits a monotonically increasing contribution to cascading conflict risks, with a plateau emerging in the medium-to-high range. When CR increases from a low value to approximately 0.2–0.3, the SHAP value rapidly turns positive, after which the growth slope decreases. This indicates that the transition from low-to-medium risk to medium-to-high risk occurs within this interval, followed by a saturation phase with diminishing marginal returns. The color coding reveals that higher local heterogeneity entropy (H) corresponds to larger SHAP values at the same preceding risk level—i.e., greater heterogeneity in traffic flow makes it easier for the same “preceding risk” to propagate backward and trigger secondary conflicts. This suggests that interactions between different types of vehicles amplify the conflict propagation effect.

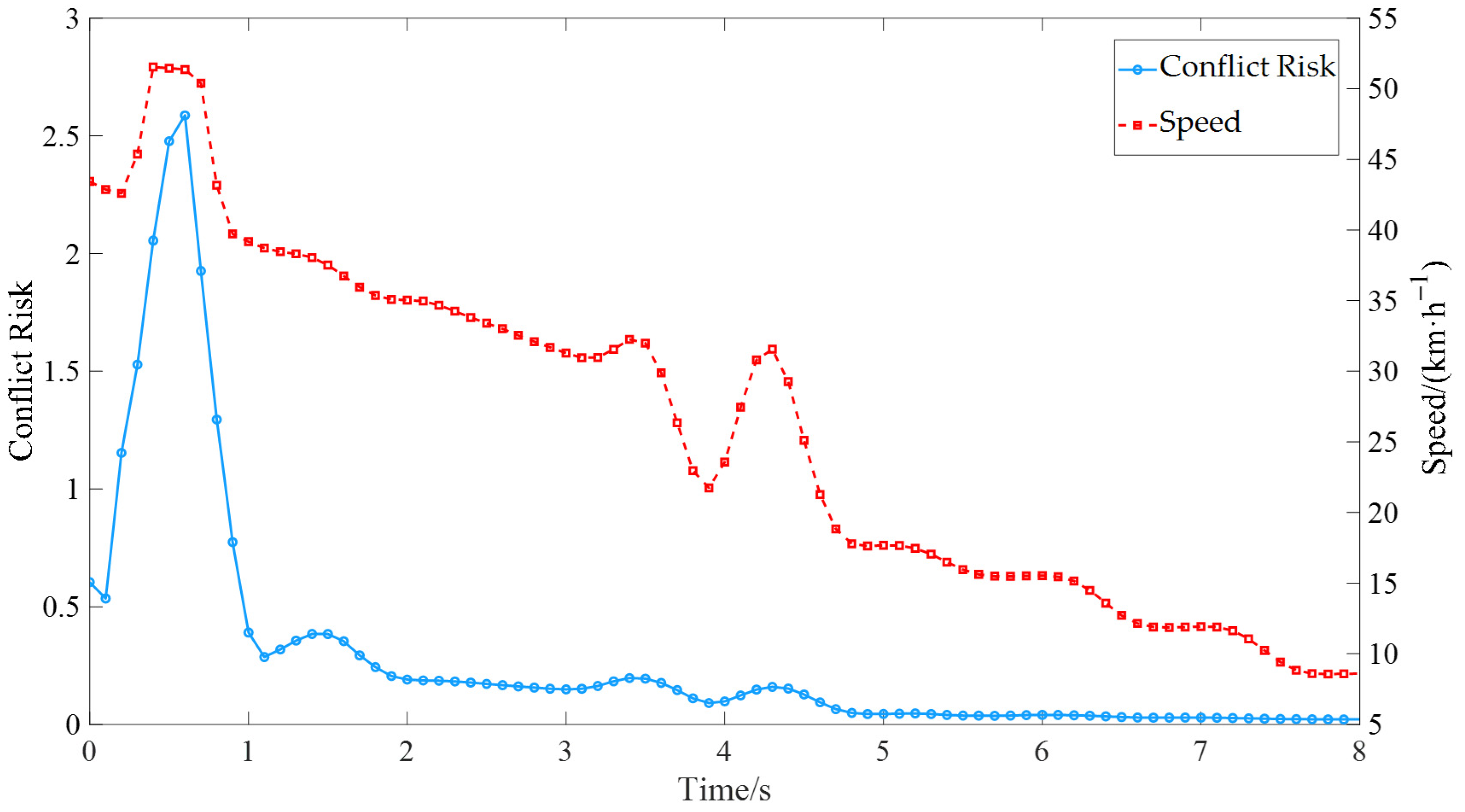

Relative speed shows a monotonically increasing trend with SHAP values, indicating that a larger speed difference between the leading and following vehicles leads to a higher risk of secondary conflict propagation. In the transition zone around Δv ≈ 1–3 m/s, the SHAP value rises sharply and crosses the zero axis (p < 0.01), meaning that even slight relative closing significantly increases risk. As the relative speed increases further, the contribution tends to saturate. The analysis also reveals its interaction with relative acceleration: at the same relative speed, a larger relative acceleration results in a higher SHAP value, indicating that the combination of “speed difference + acceleration difference” has a superlinear amplifying effect on risk. This provides a basis for joint constraints in control strategies: not only should instantaneous speed differences be suppressed, but also sudden changes in “relative acceleration” must be restricted.

The speed of the leading vehicle shows a significant negative correlation with risk contribution: the slower the leading vehicle, the higher the SHAP value. When the leading vehicle’s speed is around 40–45 km/h, the curve approaches a risk “tipping point,” beyond which risk increases sharply as speed decreases further. The color coding indicates that this negative correlation is stronger when the ego vehicle’s speed is higher (darker color), meaning that the combination of “fast ego vehicle + slow leading vehicle” is the most dangerous.

The main effect of the ego vehicle’s speed complements finding (3): the faster the ego vehicle, the higher the risk. A threshold feature appears around 50 km/h, where the SHAP value transitions from negative to positive, after which the contribution increases approximately linearly. The coloring shows that when the leading vehicle is slower, the same ego vehicle speed yields a larger SHAP value, reaffirming the critical role of speed mismatch in cascading conflict propagation.

The main effect of relative acceleration is approximately monotonically increasing with a steep slope, indicating that differences in acceleration alter the risk state more significantly than speed differences. The most pronounced jump in SHAP values occurs when relative acceleration transitions from negative to positive (i.e., changing from relative separation to relative closing). The coloring reveals that when the ego vehicle’s longitudinal acceleration is positive (accelerating), the same relative acceleration contributes more to risk, suggesting that “active acceleration by the ego vehicle during closing” is a key factor in amplifying risk.

The contribution of the ego vehicle’s acceleration generally increases with acceleration, showing asymmetry near 0 m/s2: mild braking corresponds to a limited decrease in SHAP value, whereas mild acceleration already significantly elevates risk. The coloring results indicate that when the relative acceleration is larger (indicating a stronger closing trend), the same ego acceleration leads to a higher marginal risk, reflecting the coupled amplification between individual actions and relative motion states.

Overall, dynamic interaction features account for 64.3% of the mean absolute SHAP contribution to secondary conflict risk. The rank correlation coefficients of feature importance exceed 0.9 across different random seeds and sampling ratios, demonstrating that the analytical results are stable and reliable.