Nonlinear and Spatial Effects of Housing Prices on Urban–Rural Income Inequality: Evidence from Dynamic Spatial Threshold Models in Mainland China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Theoretical Review

2.2. Linkages Between Housing and Urban and Rural Income Inequality

2.3. Modelling Issues

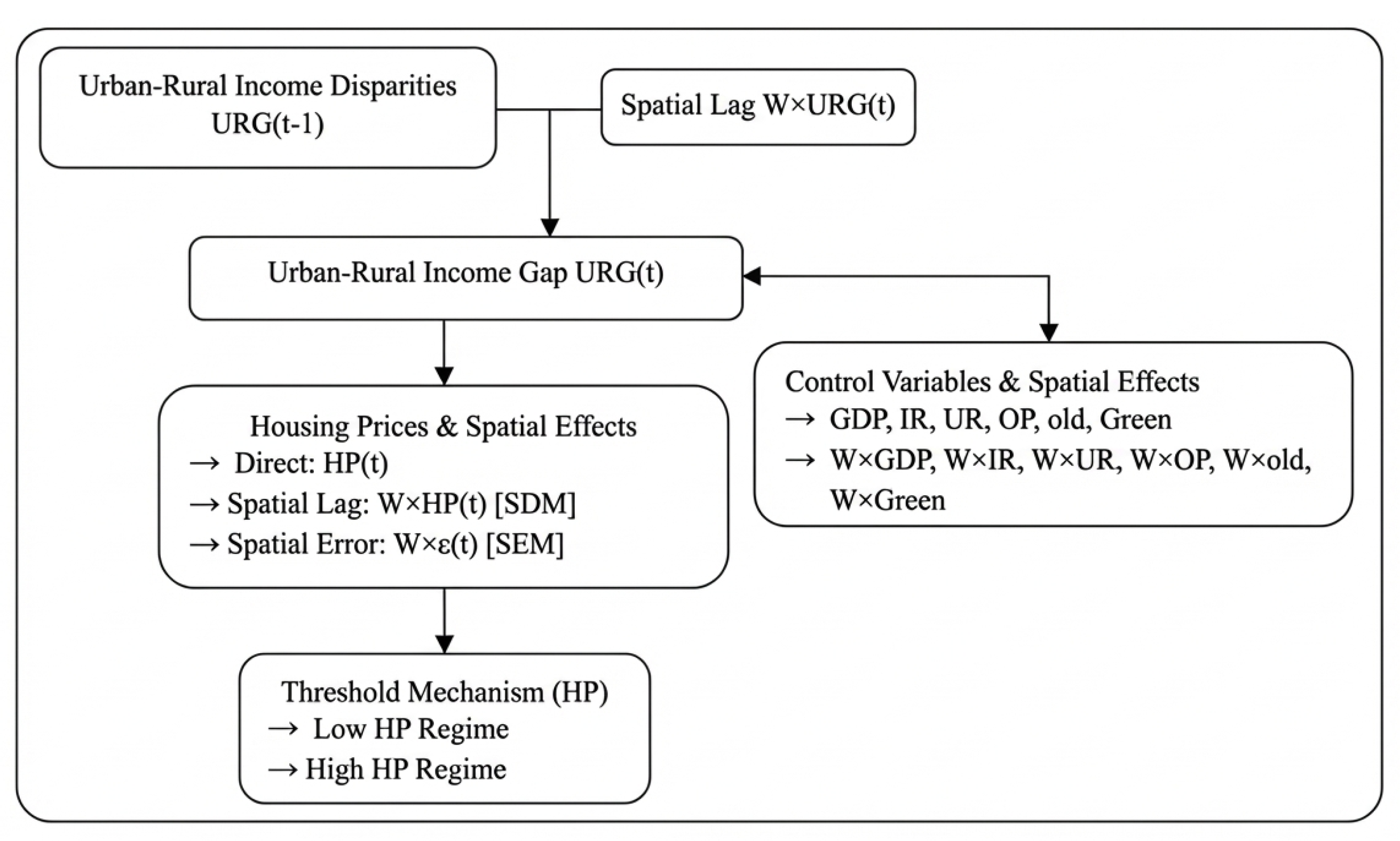

3. Research Methodology

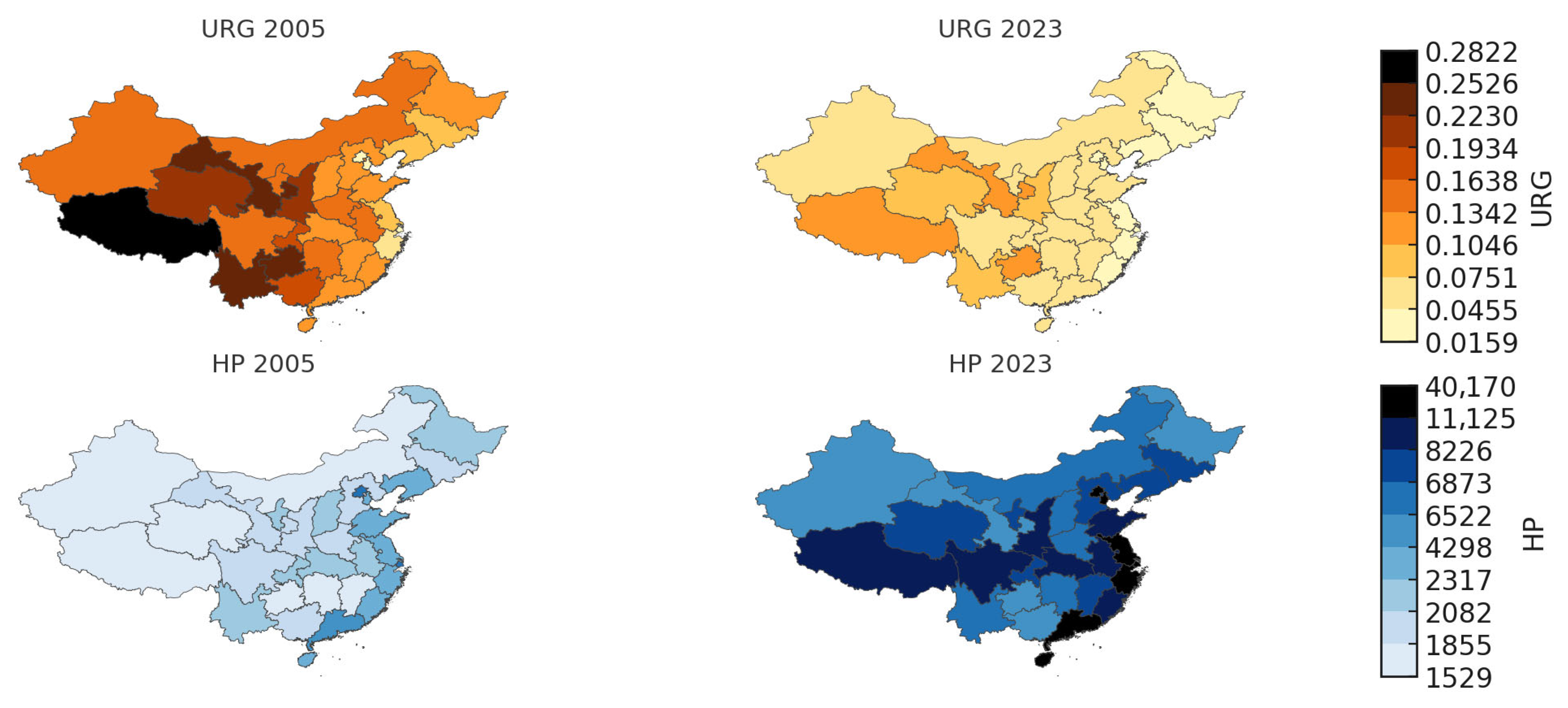

3.1. Data Collection and Variable Selection

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Spatial Dependence Testing

3.2.2. Spatial Weight Matrix Construction

3.2.3. Spatial Panel Threshold Model Specification

3.2.4. Direct and Indirect Effects Decomposition

3.2.5. Estimation via Two-Step IV (2SIV)

- Step 1 (Defactorization and instrument construction).We first remove latent common shocks from the instrument set using principal components. Let denote the matrix of latent common factors extracted from the regressors , and define the projection operator . The defactored regressors are then obtained as and . Based on these, the instrument matrix for each cross-sectional unit is constructed aswhere is the lag operator, and and denote the defactored series. This structure ensures both instrument relevance, by capturing temporal and spatial persistence—and instrument validity, by eliminating cross-sectional dependence through defactorization. These instruments are then employed in the 2SIV estimation to obtain consistent and asymptotically efficient estimates of the regime-specific parameters in the dynamic spatial threshold framework.

- Step 2 (IV on the defactored system).In the first stage, a preliminary instrumental variables (IV) estimation is conducted using the defactored model, in which latent common factors have been removed from the regressors and instruments. In the second stage, the residuals from this preliminary estimation are used to extract additional latent factors embedded in the disturbance term. The model is then re-estimated after purging these factors, thereby addressing both observed and unobserved sources of cross-sectional dependence.where , , is the projection operator removing common factors from the residual space, and is the regressor matrix. The robust variance–covariance matrix of the estimator is computed asand denotes the residual vector from the defactored system.

3.2.6. Threshold Estimation and Grid-Search Procedure

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Preliminary Tests

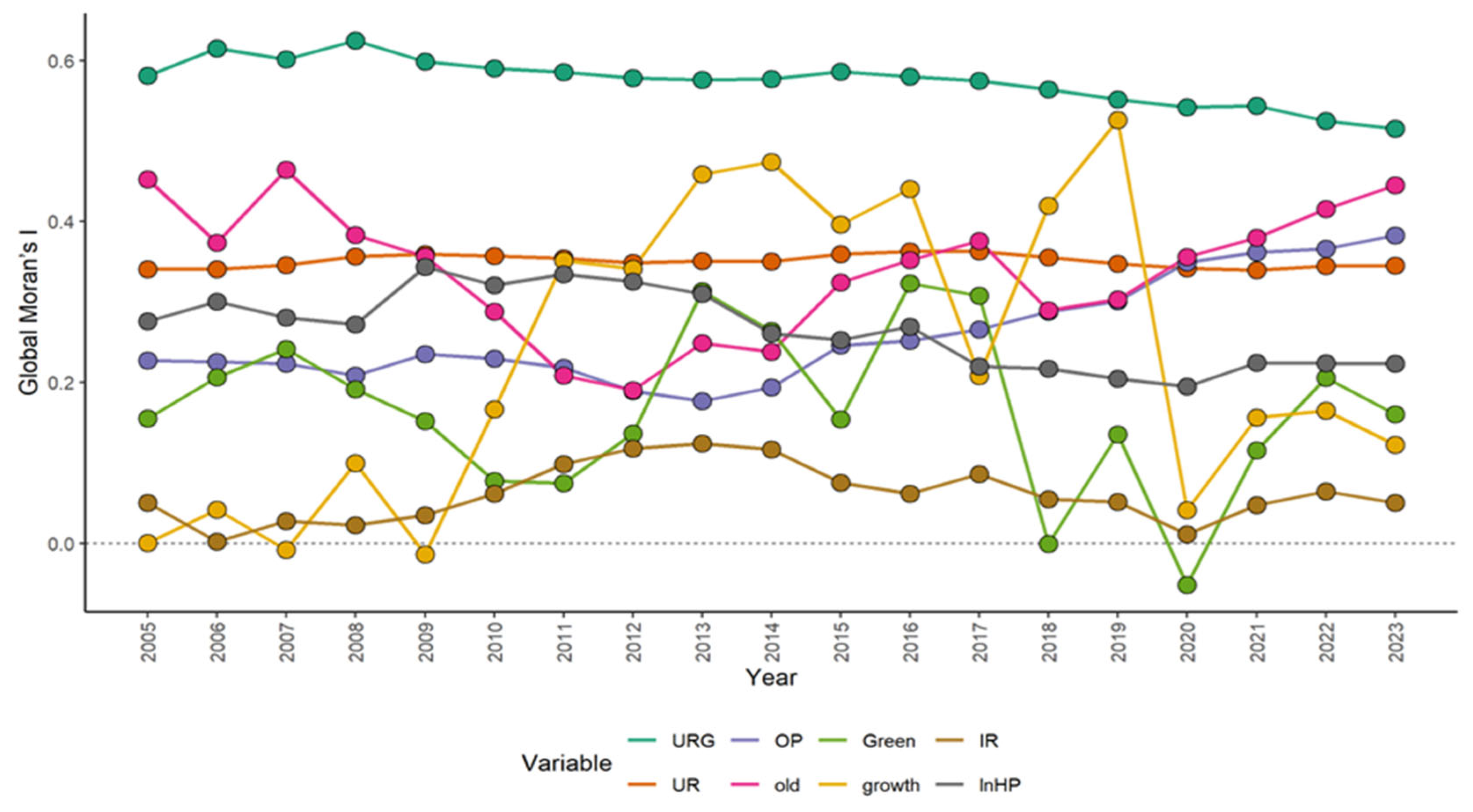

4.2. Spatial Dependence Diagnostics

4.3. Spatial Model Estimates: Linear Benchmarks and Threshold Models

4.4. Robustness Check

4.4.1. Robustness to Alternative Spatial Weight Matrix

4.4.2. Robustness to Alternative IV Estimator

4.4.3. Robustness to K-Nearest-Neighbor Spatial Weight (k = 4)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | UR | OP | Old | Green | ||||

| Model | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | Moran’s I | Geary’s C |

| 2005 | 0.3410 *** | 0.6790 ** | 0.2270 ** | 0.7690 * | 0.4520 *** | 0.5230 *** | 0.1550 * | 0.7830 ** |

| 2006 | 0.3400 *** | 0.6800 ** | 0.2260 ** | 0.7710 ** | 0.3740 *** | 0.5890 *** | 0.2060 ** | 0.6490 *** |

| 2007 | 0.3460 ** | 0.6760 ** | 0.2240 ** | 0.7720 ** | 0.4640 *** | 0.4990 *** | 0.2410 *** | 0.6280 *** |

| 2008 | 0.3560 *** | 0.6610 *** | 0.2080 ** | 0.7840 * | 0.3840 *** | 0.5740 *** | 0.1920 ** | 0.7540 ** |

| 2009 | 0.3590 *** | 0.6590 *** | 0.2350 ** | 0.7570 ** | 0.3560 *** | 0.6010 *** | 0.1520 * | 0.7880 * |

| 2010 | 0.3570 *** | 0.6520 *** | 0.2300 ** | 0.7610 ** | 0.2880 *** | 0.6550 *** | 0.0777 | 0.8510 |

| 2011 | 0.3540 *** | 0.6540 *** | 0.2180 ** | 0.7740 ** | 0.2090 * | 0.7300 ** | 0.0746 | 0.8240 * |

| 2012 | 0.3490 *** | 0.6570 *** | 0.1890 * | 0.8040 * | 0.1900 | 0.7370 ** | 0.1370 * | 0.7480 ** |

| 2013 | 0.3510 *** | 0.6530 *** | 0.1770 | 0.8160 * | 0.2490 ** | 0.6820 ** | 0.3140 *** | 0.5690 *** |

| 2014 | 0.3510 *** | 0.6520 *** | 0.1940 ** | 0.8020 * | 0.2380 ** | 0.6900 ** | 0.2640 ** | 0.5700 *** |

| 2015 | 0.3590 *** | 0.6430 *** | 0.2460 ** | 0.7500 ** | 0.3240 *** | 0.6140 *** | 0.1540 * | 0.6750 *** |

| 2016 | 0.3630 *** | 0.6390 *** | 0.2520 ** | 0.7470 ** | 0.3520 *** | 0.5860 *** | 0.3230 *** | 0.6190 *** |

| 2017 | 0.3630 *** | 0.6370 *** | 0.2660 ** | 0.7360 ** | 0.3760 *** | 0.5690 *** | 0.3080 *** | 0.5660 *** |

| 2018 | 0.3550 *** | 0.6410 *** | 0.2880 *** | 0.7190 ** | 0.2900 *** | 0.6550 *** | −0.0009 | 0.9690 |

| 2019 | 0.3470 *** | 0.6470 *** | 0.3010 ** | 0.7060 ** | 0.3040 *** | 0.6420 *** | 0.1350 * | 0.8670 |

| 2020 | 0.3420 *** | 0.6500 *** | 0.3490 *** | 0.6610 ** | 0.3560 *** | 0.5740 *** | −0.0515 | 1.0400 |

| 2021 | 0.3400 ** | 0.6500 *** | 0.3620 *** | 0.6460 *** | 0.3800 *** | 0.5450 *** | 0.1150 | 0.8760 |

| 2022 | 0.3440 *** | 0.6450 *** | 0.3660 *** | 0.6420 *** | 0.4160 *** | 0.5110 *** | 0.2060 ** | 0.8410 |

| 2023 | 0.3450 *** | 0.6440 ** | 0.3830 *** | 0.6290 *** | 0.4450 *** | 0.4830 *** | 0.1610 * | 0.8970 |

| Year | Growth | IR | lnHP | |||||

| Model | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | ||

| 2005 | 0.0002 | 0.9360 | 0.0505 | 0.9030 | 0.2760 ** | 0.7240 ** | ||

| 2006 | 0.0420 | 0.9580 | 0.0021 | 0.9510 | 0.3000 *** | 0.6960 ** | ||

| 2007 | −0.0082 | 0.9440 | 0.0279 | 0.9310 | 0.2800 ** | 0.7120 ** | ||

| 2008 | 0.0998 | 0.8830 | 0.0223 | 0.9320 | 0.2720 ** | 0.7270 ** | ||

| 2009 | −0.0136 | 0.9730 | 0.0352 | 0.9120 | 0.3440 *** | 0.6560 ** | ||

| 2010 | 0.1670 * | 0.7630 ** | 0.0617 | 0.8920 | 0.3210 *** | 0.6710 *** | ||

| 2011 | 0.3510 *** | 0.6200 *** | 0.0984 | 0.8620 | 0.3350 *** | 0.6570 *** | ||

| 2012 | 0.3410 *** | 0.7040 ** | 0.1180 | 0.8400 | 0.3260 *** | 0.6600 *** | ||

| 2013 | 0.4590 *** | 0.5970 *** | 0.1240 | 0.8270 * | 0.3100 *** | 0.6790 ** | ||

| 2014 | 0.4740 *** | 0.5520 *** | 0.1170 | 0.8300 * | 0.2610 ** | 0.7200 ** | ||

| 2015 | 0.3960 *** | 0.6180 *** | 0.0752 | 0.8590 | 0.2530 ** | 0.7300 ** | ||

| 2016 | 0.4400 *** | 0.5480 *** | 0.0618 | 0.8710 | 0.2690 *** | 0.7180 ** | ||

| 2017 | 0.2080 * | 0.7860 * | 0.0858 | 0.8540 | 0.2200 * | 0.7640 * | ||

| 2018 | 0.4200 *** | 0.5350 *** | 0.0546 | 0.8790 | 0.2170 ** | 0.7680 ** | ||

| 2019 | 0.5260 *** | 0.4240 *** | 0.0513 | 0.8840 | 0.2050 * | 0.7820 * | ||

| 2020 | 0.0410 | 0.8880 | 0.0112 | 0.9210 | 0.1950 | 0.7930 * | ||

| 2021 | 0.1560 * | 0.8060 | 0.0473 | 0.8900 | 0.2240 * | 0.7660 ** | ||

| 2022 | 0.1650 * | 0.7640 ** | 0.0647 | 0.8840 | 0.2240 * | 0.7700 ** | ||

| 2023 | 0.1220 | 0.8180 * | 0.0502 | 0.8960 | 0.2230 ** | 0.7730 * | ||

References

- Knight, J.; Deng, Q.; Li, S. The puzzle of migrant labour shortage and rural labour surplus in China. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Brueckner, M. Inequality and growth in China. Empir. Econ. 2024, 66, 539–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicular, T.; Ximing, Y.; Gustafsson, B.; Shi, L. The urban–rural income gap and inequality in China. Rev. Income Wealth 2007, 53, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ma, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ji, Z. The impact of digital economy on income inequality from the perspective of technological progress-biased transformation: Evidence from China. Empir. Econ. 2024, 67, 567–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.H.; Song, S. Rural–urban migration and urbanization in China: Evidence from time-series and cross-section analyses. China Econ. Rev. 2003, 14, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ma, Y. Effect of industrial structure on urban–rural income inequality in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. International trade and urban-rural income inequality in China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 31, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xue, J.; Qian, J.; Qian, X. Mapping energy inequality between urban and rural China. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 165, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Gyourko, J. The economic implications of housing supply. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, C.A.; Robert-Nicoud, F. On the origins of land use regulations: Theory and evidence from US metro areas. J. Urban Econ. 2013, 75, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.; Ho, S.P. The state, land system, and land development processes in contemporary China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Murie, A. Social and spatial implications of housing reform in China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2000, 24, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Coulson, N.E. Determinants of urban migration: Evidence from Chinese cities. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, C.; Hedlund, A.; Tang, Y.; Wang, P. Rural–urban migration and house prices in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 91, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Hui, E.C.M.; Sun, J.X. Population migration, urbanization and housing prices: Evidence from the cities in China. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, S. Spatial heterogeneity analysis of biased land resource supply policies on housing prices and innovation efficiency. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, P. Spatial inequality in China’s housing market and the driving mechanism. Land 2021, 10, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C.; Fitzenberger, B.; Zimmermann, M. Housing expenditure and income inequality. Econ. J. 2022, 132, 1709–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Smyth, R.; Baako, K.T. Income inequality and housing prices in the very long run. South. Econ. J. 2021, 88, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T.; Saez, E. Inequality in the long run. Science 2014, 344, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelino, M.; Schoar, A.; Severino, F. House prices, collateral, and self-employment. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 117, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Gottlieb, J.D. The wealth of cities: Agglomeration economies and spatial equilibrium in the United States. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 983–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.C.; Su, C.W. Have housing prices contributed to regional imbalances in urban–rural income gap in China? J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 2139–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, X.; Dong, Y. The causes of income inequality in urban China: A household assets perspective. Chin. J. Sociol. 2024, 10, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFusco, A.; Ding, W.; Ferreira, F.; Gyourko, J. The role of price spillovers in the American housing boom. J. Urban Econ. 2018, 108, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, J.M.; Raphael, S. Is housing unaffordable? Why isn’t it more affordable? J. Econ. Perspect. 2004, 18, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguena, C.L.; Tchana Tchana, F.; Zeufack, A. On threshold effect of housing finance on shared prosperity: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Bull. Econ. Res. 2024, 76, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Qian, J.; Liu, G.; Wu, Y.; Delang, C.O.; He, H. Housing prices and household consumption: A threshold effect model analysis in central and western China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V. The sizes and types of cities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1974, 64, 640–656. [Google Scholar]

- Roback, J. Wages, rents, and the quality of life. J. Political Econ. 1982, 90, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jia, S.; Yang, R. Housing affordability and housing vacancy in China: The role of income inequality. J. Hous. Econ. 2016, 33, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Loayza, N. Finance and the sources of growth. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.; Sufi, A. House of Debt: How They (And You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Favilukis, J.; Ludvigson, S.C.; Van Nieuwerburgh, S. The macroeconomic effects of housing wealth, housing finance, and limited risk sharing in general equilibrium. J. Political Econ. 2017, 125, 140–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, K.; Sullivan, P. Implications of US tax policy for house prices, rents, and homeownership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R.; Zhang, X. Fifty years of regional inequality in China: A journey through central planning, reform, and openness. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2005, 9, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, R.C.; Hanson, G.H. Global production sharing and rising inequality: A survey of trade and wages. Handb. Int. Trade 2003, 1, 146–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Fink, G. Implications of population aging for economic growth. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2010, 26, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyovanyi, M.; Nepochatenko, Z.; Osipova, A.; Novak, I.; Prokopchuk, O. The impact of population ageing on economic growth: The role of social policy models in OECD countries. Financ. Credit. Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2025, 4, 538–557. [Google Scholar]

- Umair, M.; Aizhan, A.; Teymurova, V.; Chang, L. Does the disparity between rural and urban incomes affect rural energy poverty? Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 56, 101584. [Google Scholar]

- Ünalan, G.; Çamalan, Ö.; Yılmaz, H.H. The impact of increases in housing prices on income inequality: A perspective on sustainable urban development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, M.S.; Setyowati, N.; Cheng, C.Y.; Cheng, Y.S. The nonlinear relationship between housing prices and income inequality. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2025, 40, 1089–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rhee, D.E. The effects of asset prices on income inequality: Redistribution policy does matter. Econ. Model. 2022, 113, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, Y.M.; Ngai, L.R. Housing and inequality. J. Econ. Lit. 2025, 63, 916–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T. Spatial inequality and housing in China. J. Urban Econ. 2023, 134, 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Cui, C.; Cui, J. Housing differentiation from the spatial opportunity structure perspective: An empirical study on new-generation migrants in China. J. Chin. Sociol. 2024, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X. Urban expansion and the urban–rural income gap: Empirical evidence from China. Cities 2022, 129, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.P.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chica-Olmo, J.; Sari-Hassoun, S.; Moya-Fernández, P. Spatial relationship between economic growth and renewable energy consumption in 26 European countries. Energy Econ. 2020, 92, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, S. Energy investment, economic growth and carbon emissions in China—Empirical analysis based on spatial Durbin model. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, M.; Heshmati, A.; Khodaei, M. The role of R&D in the effectiveness of renewable energy determinants: A spatial econometric analysis. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Wei, J. Are house prices affected by PM2.5 pollution? Evidence from Beijing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, E. Real wage inequality. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2013, 5, 65–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Sarafidis, V.; Yamagata, T. IV estimation of spatial dynamic panels with interactive effects: Large sample theory and an application on bank attitude towards risk. Econom. J. 2023, 26, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Bera, A.K.; Florax, R.; Yoon, M.J. Simple diagnostic tests for spatial dependence. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1996, 26, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; De Jong, R.; Lee, L.F. Quasi-maximum likelihood estimators for spatial dynamic panel data with fixed effects when both n and T are large. J. Econom. 2008, 146, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, S.; Sarafidis, V. Estimating Spatial Dynamic Panel Data Models with Unobserved Common Factors in Stata. J. Stat. Softw. 2025, 113, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Calculation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||

| URG | Urban–rural income gap | See Equation (1) | NBS China |

| Measurement | |||

| RUI | Real urban income | Nominal urban income/CPI × 100 | NBS China |

| RRI | Real rural income | Nominal rural income/CPI × 100 | NBS China |

| UP | Urban population | Permanent urban residents | NBS China |

| RP | Rural population | Permanent rural residents | NBS China |

| Independent Variables | |||

| HP | Housing prices | Average commercial housing price per m2 | NBS China |

| Control Variables | |||

| Growth | GDP growth rate | ln()ln() | NBS China |

| OP | Trade openness | Provincial annual increment of import and export trade volume/Provincial GDP × 100% | NBS China |

| IR | Industrialization rate | Provincial annual increment of industrial added value/Provincial GDP × 100% | NBS China |

| UR | Urbanization rate | Urban population/Total population × 100% | NBS China |

| Green | Green investment ratio | Green investment/Provincial GDP × 100% | NBS China |

| OLD | Old-age Dependency Ratio | Population aged 60+/Population aged 15–59 × 100% | CEIC |

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| URG | 0.0159 | 0.2822 | 0.0993 | 0.0500 | 0.782 | 0.5674 |

| UR | 0.2261 | 0.8960 | 0.5596 | 0.1460 | 0.3414 | −0.0680 |

| OP | 0.0076 | 1.7999 | 0.2906 | 0.3461 | 2.2612 | 5.0003 |

| OLD | 0.0670 | 0.3060 | 0.1475 | 0.0456 | 0.9161 | 0.3454 |

| Green | 0.0005 | 0.0463 | 0.0118 | 0.0078 | 1.6729 | 3.6044 |

| Growth | −0.0548 | 0.2609 | 0.1092 | 0.0574 | 0.2001 | −0.4963 |

| IR | 0.1491 | 0.6196 | 0.4163 | 0.0846 | −0.6854 | 0.7044 |

| HP | 1528.6800 | 40,526.0000 | 6987.1300 | 5816.0900 | 3.1849 | 12.8456 |

| Variable | CD Test | LM Test | Scaled LM Test | Bias-Corrected Scaled LM Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| URG | 90.9910 *** | 8287.64 *** | 256.5143 *** | 255.6532 *** |

| lnUR | 88.9428 *** | 8044.72 *** | 248.5487 *** | 247.6875 *** |

| lnOP | 21.5912 *** | 3100.98 *** | 86.4372 *** | 85.5761 *** |

| lnOLD | 82.3528 *** | 7125.74 *** | 218.4143 *** | 217.5532 *** |

| lnGreen | 45.6605 *** | 2859.45 *** | 78.5172 *** | 77.6561 *** |

| Growth | 89.2936 *** | 7975.0220 *** | 246.2633 *** | 245.3516 *** |

| lnIR | 51.3862 *** | 4849.80 *** | 143.7834 *** | 142.9223 *** |

| lnHP | 90.9635 *** | 8277.98 *** | 256.1978 *** | 255.3367 *** |

| Variable | CIPS (T-bar) | LLC | IPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| URG | −3.0735 *** | −2.6321 *** | −2.9097 *** |

| lnUR | −2.9203 *** | −3.3606 *** | −7.1316 *** |

| lnOP | −1.8609 * | −2.0914 *** | −2.9397 *** |

| lnOLD | −1.7980 * | −11.4288 *** | −7.6870 *** |

| lnGreen | −2.1883 ** | −4.2367 *** | −2.4634 ** |

| Growth | −2.4719 ** | −12.0474 *** | −7.8405 *** |

| lnIR | −1.7948 * | −4.5180 *** | −2.5872 *** |

| lnHP | −1.6623 * | −8.0505 *** | −5.7838 *** |

| Variable | lnHP | lnUR | Growth | lnOP | lnIR | lnOLD | lnGreen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnHP | 1.0000 | 0.8141 | −0.4748 | 0.4835 | −0.4691 | 0.4383 | −0.2876 |

| lnUR | 0.8141 | 1.0000 | −0.4030 | 0.6440 | −0.2553 | 0.4406 | −0.1562 |

| Growth | −0.4748 | −0.4030 | 1.0000 | 0.0437 | 0.2977 | −0.4247 | 0.1584 |

| lnOP | 0.4835 | 0.6440 | 0.0437 | 1.0000 | −0.1158 | 0.0131 | −0.0931 |

| lnIR | −0.4691 | −0.2553 | 0.2977 | −0.1158 | 1.0000 | −0.1842 | 0.1847 |

| lnOLD | 0.4383 | 0.4406 | −0.4247 | 0.0131 | −0.1842 | 1.0000 | −0.4312 |

| lnGreen | −0.2876 | −0.1562 | 0.1584 | −0.0931 | 0.1847 | −0.4312 | 1.0000 |

| VIF | 4.1651 | 5.1865 | 1.6250 | 2.4049 | 1.3835 | 1.8516 | 1.3592 |

| Year | Moran’s I | Geary’s C | Year | Moran’s I | Geary’s C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 0.5814 *** | 0.4433 *** | 2015 | 0.5865 *** | 0.4693 *** |

| 2006 | 0.6152 *** | 0.4385 *** | 2016 | 0.5799 *** | 0.4746 *** |

| 2007 | 0.6017 *** | 0.4518 *** | 2017 | 0.5751 *** | 0.4803 *** |

| 2008 | 0.6248 *** | 0.4200 *** | 2018 | 0.5642 *** | 0.4893 *** |

| 2009 | 0.5989 *** | 0.4508 *** | 2019 | 0.5515 *** | 0.5033 *** |

| 2010 | 0.5903 *** | 0.4611 *** | 2020 | 0.5421 *** | 0.5135 *** |

| 2011 | 0.5858 *** | 0.4763 *** | 2021 | 0.5437 *** | 0.5094 *** |

| 2012 | 0.5782 *** | 0.4877 *** | 2022 | 0.5249 *** | 0.5309 *** |

| 2013 | 0.5758 *** | 0.4900 *** | 2023 | 0.5153 *** | 0.5425 *** |

| 2014 | 0.5773 *** | 0.4875 *** | Average | 0.5743 *** | 0.4800 *** |

| LM Test | Cross-Section | Panel Residuals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | p-Value | Statistic | p-Value | |

| LM-lag | 3.2683 | 0.0706 | 152.6598 | 0.0000 |

| Robust LM-lag | 3.3641 | 0.0666 | 102.9329 | 0.0000 |

| LM-error | 0.2827 | 0.5949 | 62.7925 | 0.0000 |

| Robust LM-error | 0.3786 | 0.5384 | 13.0656 | 0.0003 |

| Variable | Cross-Section | Panel FE |

|---|---|---|

| lnHP | −0.0477 * (0.0280) | 0.0071 * (0.0041) |

| lnUR | −0.2038 ** (0.0841) | −0.1596 *** (0.0192) |

| lnOP | 0.0444 (0.0340) | −0.0361 *** (0.0040) |

| lnOLD | −0.1075 (0.1601) | 0.1523 *** (0.0262) |

| lnGreen | 0.2610 (1.1676) | −0.1713 ** (0.0761) |

| Growth | 0.7093 ** (0.3401) | −0.0450 *** (0.0150) |

| lnIR | −0.1017 (0.0654) | −0.0643 *** (0.0130) |

| Parameter | DSDM | DSAR | DSEM | OLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| URG_lag | 0.6869 *** (0.0228) | 0.6834 *** (0.0226) | 0.7169 *** (0.0216) | 0.7482 *** (0.0222) |

| lnHP | 0.0057 *** (0.0021) | 0.0057 *** (0.0021) | 0.0037 * (0.0022) | 0.0043 * (0.0023) |

| Growth | −0.0134 * (0.0070) | −0.0140 ** (0.0070) | −0.0120 * (0.0072) | −0.0156 ** (0.0077) |

| lnOP | −0.0059 *** (0.0021) | −0.0058 *** (0.0021) | −0.0055 *** (0.0021) | −0.0053 ** (0.0023) |

| lnIR | −0.0043 (0.0063) | −0.0038 (0.0063) | −0.0033 (0.0062) | −0.0034 (0.0069) |

| lnOLD | −0.0015 (0.0131) | −0.0030 (0.0129) | 0.0182 (0.0132) | 0.0194 (0.0135) |

| lnGreen | −0.0047 (0.0350) | −0.0123 (0.0348) | −0.0393 (0.0355) | −0.0218 (0.0379) |

| lnUR | −0.0640 *** (0.0100) | −0.0665 *** (0.0100) | −0.0732 *** (0.0103) | −0.0707 *** (0.0109) |

| W×nHP | 0.0020 (0.0012) | - | - | - |

| W×Growth | 0.0054 (0.0072) | - | - | - |

| W×lnOP | −0.0020 (0.0016) | - | - | - |

| W×lnIR | 0.0002 (0.0044) | - | - | - |

| W×lnOLD | 0.0034 (0.0095) | - | - | - |

| W×lnGreen | 0.0492 (0.0472) | - | - | |

| ρ (W×URG) | 0.1441 *** (0.0240) | 0.1435 *** (0.0241) | - | - |

| υ | - | - | 0.2407 *** (0.0493) | - |

| F Statistic | 222.2006 *** | 416.3802 *** | 380.7359 *** | 384.0957 *** |

| Log-likelihood | 2291.0080 | 2287.4760 | 1304.3860 | - |

| Adj-R2 | 0.8705 | 0.8688 | 0.8583 | 0.8593 |

| J test | 18.136 [0.409] | 24.119 [0.191] | 10.813 [0.290] |

| Parameter | DSTDM | DSTARM | DSTEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold value γ | 8.4843 *** | 8.5211 *** | 8.5092 *** |

| URG_lag | 0.6901 *** | 0.6876 *** | 0.7206 *** |

| lnHP.L | 0.0085 ** | 0.0076 *** | 0.0057 *** |

| lnHP.H | 0.0060 *** | 0.0064 *** | 0.0045 ** |

| lnGreen | −0.0047 | −0.0103 | −0.0344 |

| Growth | −0.0136 ** | −0.0140 ** | −0.0127 * |

| lnIR | −0.0049 | −0.0041 | −0.0040 |

| lnOLD | 0.0010 | −0.0011 | 0.0189 |

| lnOP | −0.0057 *** | −0.0056 *** | −0.0055 *** |

| lnUR | −0.0616 *** | −0.0640 *** | −0.0704 *** |

| W×nHP.L | 0.0022 | - | - |

| W×lnHP.H | 0.0017 | - | - |

| W×lnGreen | 0.0295 | - | - |

| W×Growth | 0.0034 | - | - |

| W×lnIR | 0.0007 | - | - |

| W×lnOLD | 0.0015 | ||

| W×lnOP | −0.0200 | - | - |

| W×lnUR | −0.0050 | - | - |

| (W×URG) | 0.1336 *** | 0.1498 *** | - |

| ν | - | - | 0.2073 *** |

| F Statistic | 199.9382 *** | 378.8045 *** | 350.5127 *** |

| Log-likelihood | 2296.961 | 2293.791 | 1310.465 |

| R2 | 0.8731 | 0.8717 | 0.8627 |

| J test | 7.204 [0.391] | 4.801 [0.698] | 10.092 [0.302] |

| Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnHP.L | 0.0081 | 0.0026 | 0.0107 |

| lnHP.H | 0.0054 | 0.0029 | 0.0083 |

| Growth | −0.0135 | 0.0018 | −0.0117 |

| lnIR | −0.0049 | 0.0001 | −0.0048 |

| lnOLD | 0.0010 | 0.0019 | 0.0029 |

| lnUR | −0.0621 | −0.0149 | −0.0769 |

| lnOP | −0.0058 | −0.0031 | −0.0089 |

| lnGreen | −0.0038 | 0.0324 | 0.0286 |

| Parameter | DSDM | DSAR | DSEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold value γ | 8.4024 *** | 8.4223 *** | 8.4010 *** |

| URG_lag | 0.6828 *** | 0.6851 *** | 0.7329 *** |

| lnHP.L | 0.0063 ** | 0.0066 *** | 0.0061 *** |

| lnHP.H | 0.0049 *** | 0.0052 *** | 0.0048 ** |

| W×lnHP.L | 0.0018 | - | - |

| W×lnHP.H | 0.0017 | - | - |

| (W×URG) | 0.1708 *** | 0.1716 *** | - |

| ν | - | - | 0.1433 *** |

| F Statistic | 201.553 *** | 383.894 *** | 352.047 *** |

| Log-likelihood | 2297.719 | 2295.812 | 1307.795 |

| R2 | 0.8740 | 0.8731 | 0.8632 |

| J test | 10.134 [0.290] | 5.019 [0.145] | 18.224 [0.415] |

| Parameter | DSDM | DSAR | DSEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold value γ | 8.4843 *** | 8.5211 *** | 8.5092 *** |

| URG_lag | 0.5003 *** | 0.7294 *** | 0.2034 *** |

| lnHP.L | 0.0102 * | 0.0089 ** | 0.0093 ** |

| lnHP.H | 0.0052 ** | 0.0037 ** | 0.0052 ** |

| W×nHP.L | 0.0020 | - | - |

| W×lnHP.H | 0.0003 | - | - |

| (W×URG) | 0.1003 *** | 0.1210 *** | - |

| ν | - | - | 0.1433 *** |

| F Statistic | 197.192 *** | 312.909 *** | 323.103 *** |

| Log-likelihood | 2102.596 | 2156.390 | 1173.302 |

| R2 | 0.8834 | 0.8221 | 0.8340 |

| J test | 15.245 [0.427] | 3.235 [0.101] | 8.113 [0.208] |

| Parameter | DSDM | DSAR | DSEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold value γ | 8.4843 *** | 8.5211 *** | 8.5092 *** |

| URG_lag | 0.6911 *** | 0.6872 *** | 0.7210 *** |

| lnHP.L | 0.0083 ** | 0.0076 *** | 0.0059 *** |

| lnHP.H | 0.0061 *** | 0.0063 *** | 0.0043 ** |

| W×lnHP.L | 0.0021 | - | - |

| W×lnHP.H | 0.0018 | - | - |

| (W×URG) | 0.1333 *** | 0.1493 *** | - |

| ν | - | - | 0.2071 *** |

| F Statistic | 201.220 *** | 379.102 *** | 351.023 *** |

| Log-likelihood | 2299.203 | 2297.203 | 1315.210 |

| R2 | 0.8732 | 0.8717 | 0.8627 |

| J test | 7.199 [0.387] | 4.796 [0.699] | 10.100 [0.300] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Yamaka, W.; Maneejuk, P. Nonlinear and Spatial Effects of Housing Prices on Urban–Rural Income Inequality: Evidence from Dynamic Spatial Threshold Models in Mainland China. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243960

Li M, Yamaka W, Maneejuk P. Nonlinear and Spatial Effects of Housing Prices on Urban–Rural Income Inequality: Evidence from Dynamic Spatial Threshold Models in Mainland China. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243960

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Mingyang, Woraphon Yamaka, and Paravee Maneejuk. 2025. "Nonlinear and Spatial Effects of Housing Prices on Urban–Rural Income Inequality: Evidence from Dynamic Spatial Threshold Models in Mainland China" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243960

APA StyleLi, M., Yamaka, W., & Maneejuk, P. (2025). Nonlinear and Spatial Effects of Housing Prices on Urban–Rural Income Inequality: Evidence from Dynamic Spatial Threshold Models in Mainland China. Mathematics, 13(24), 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243960