1. Introduction

Model evaluation is central to the scientific value of machine learning (ML): the chosen metric defines what counts as reliable performance for a given application and directly shapes model selection and deployment decisions. Because different metrics emphasize different aspects of behavior (e.g., error rate versus sensitivity to class imbalance), they can rank the same models differently on the same data [

1]. In safety-critical contexts, this makes the metric choice part of the problem specification itself, since it encodes which kinds of errors the system must avoid and how uneven class performance should be properly penalized [

2].

There exists a wide ecosystem of performance indices—accuracy and error rate, class-conditional sensitivity/recall,

-scores [

3,

4], rank-based and agreement-based measures such as Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [

5] and Cohen’s

[

6], the ROC curve [

7,

8,

9], and multiclass generalizations—each with distinct statistical and operational semantics [

10,

11,

12]. This richness is useful but hazardous if metrics are chosen without regard to data and objectives, or when reported scores are internally inconsistent [

13].

In many applications the target (positive) class is rare (e.g., fraud, medical screening, fault detection); more broadly, in multiclass settings one or more classes may have very low prevalence—despite being equally important as the common classes—so imbalance manifests as uneven per-class prevalences rather than a single positive–negative asymmetry. Under such class imbalance, metrics that mix class-conditional terms (probabilities conditioned on the true class; e.g., true positive rate) with class priors (unconditional probabilities of each class, i.e., class proportions) can be dominated by the majority class, masking poor minority performance. Foundational studies and surveys document both the ubiquity of imbalance and its effects on learning and evaluation [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Consequently, conclusions drawn from prevalence-sensitive metrics can be unstable across datasets that differ only in class proportions.

When the scientific goal is to develop a predictive model that is accurate and reliable, it is preferable to base model selection and validation on prevalence-insensitive criteria that reflect intrinsic class-conditional performance. Using aggregates of per-class sensitivity and threshold-free analyses (e.g., Multiclass Classification Performance (MCP) [

18]) decouples model quality from the class prior, yielding estimates that remain stable under base-rate shifts. Operational costs and prevalences can then be incorporated at deployment through decision analysis, without confounding model selection with prevalence effects [

19].

Thus, a principled route to prevalence-insensitivity is to construct evaluation indices from the class-conditional true positive rate (sensitivity) and true negative rate (specificity)—and, in the multiclass case, from per-class sensitivities. Because these are conditioned on the true class, they are invariant to changes in prevalence and thus provide a stable basis for summary measures [

20].

Aggregating sensitivity (and specificity) via the Pythagorean means (arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic) yields class-symmetric, prevalence-insensitive summaries with different penalizations of imbalance between components. This means-based perspective makes explicit how the choice of mean encodes the desired conservativeness against asymmetric errors, while remaining robust to class-prior changes [

21,

22].

For binary datasets, the arithmetic mean (balanced accuracy),

, and the geometric mean,

, are widely reported in imbalanced-learning research, whereas the harmonic mean,

, of sensitivity and specificity is comparatively rare despite its appealingly conservative nature. Its use is documented in domain-specific studies (e.g., biomedical diagnostics), yet it remains less common as a headline metric than balanced accuracy or the

G-mean in general ML practice [

23,

24,

25]. In multiclass settings, the harmonic mean of per-class true positive rates is even less common, despite its ability to reveal weak per-class performance in critical systems.

In safety-critical diagnosis, the evaluation criterion must encode minimum class-wise detection requirements and remain stable under prevalence shifts; otherwise, aggregate scores can coexist with unacceptable under-detection of specific conditions. Adopting prevalence-insensitive, class-symmetric summaries built from per-class sensitivities—and, in particular, the harmonic mean—aligns model selection with clinical safety by rewarding uniformly adequate coverage rather than compensatory trade-offs. This choice yields estimates that are robust across datasets and supports transparent auditing of class-wise performance.

This paper advocates prevalence-insensitive evaluation in critical domains and, in particular, the use of measures built from per-class true positive rates. It addresses three shortcomings in current practice: (i) the widespread reliance on prevalence-sensitive indices—such as accuracy and F-score—whose values vary with class proportions and can therefore overstate reliability under imbalance; (ii) the absence of a conservative, class-symmetric summary that prevents high overall scores when any class is under-detected; and (iii) the scarcity of multiclass-oriented formulations that remain invariant to base-rate shifts while retaining clear interpretability.

On the UCI benchmarks, we observe a modest yet systematic overestimation by global metrics relative to class-symmetric means. In the multiclass cancer case study, high overall scores coexist with low per-class sensitivities for several tumor types; these global aggregates mask class-specific weaknesses and can lead to missed diagnoses with serious clinical consequences. In summary, these findings support the harmonic mean as a prudent, conservative choice to mitigate overestimation when some classes exhibit weak sensitivity.

Our contributions are: (i) a formal analysis that separates prevalence-sensitive from prevalence-insensitive measures by examining their dependence on class priors; (ii) a systematic treatment that frames the Pythagorean means—arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic—as class-symmetric aggregators of true-positive rates (binary: sensitivity and specificity; multiclass: per-class sensitivities); (iii) practical guidance for safety-critical evaluation, recommending the harmonic mean of per-class sensitivities as a conservative, imbalance-robust summary; and (iv) empirical validation across standard benchmarks and a high-dimensional, 35-class cancer diagnosis task, demonstrating consistent gaps between accuracy-like indices and prevalence-insensitive summaries.

2. Prevalence-Insensitive vs. Prevalence-Sensitive Measures

Let with , where denotes the positive class and the negative class. A (deterministic) classifier is a mapping . More generally, a scoring model outputs a function , which is converted into a classifier by thresholding: for , the induced classifier is . Let denote the positive-class prevalence (so ). We write for the indicator of an event E, equal to 1 if E holds, and 0 otherwise.

Performance summaries aggregate different types of errors that have distinct operational meaning. Global metrics that average over classes (e.g., overall accuracy) depend on the class prior , while class-conditional rates are prevalence-invariant and thus separate the intrinsic discriminative ability of a classifier from the composition of the test population.

For a sample

and a fixed classifier

, define the counts

Let

and

be the numbers of positive and negative instances, with

. The confusion matrix is shown in

Table 1.

The fundamental class-conditional rates are

These rates quantify, respectively, sensitivity to positives, specificity to negatives, and the spurious activation rate on negatives. Because they are conditional on the true class, and are invariant to changes in .

In binary classification with class label

, the prevalence

(class prior) can be highly skewed. Class imbalance is ubiquitous in ML and profoundly affects model selection and metric interpretation [

14,

15,

16]. A central distinction is between prevalence-insensitive (class-imbalance-invariant) measures—those that depend only on class-conditional performance—and prevalence-sensitive measures—those whose values change with

even if the class-conditional behavior of the classifier remains fixed. Below we structure key measures into these two groups and formalize their dependence.

2.1. Prevalence-Insensitive (Class-Imbalance-Invariant) Measures

Let

(sensitivity) and

(specificity), as defined in Equation (

2). These class-conditional rates are invariant to

by definition. Several standard summaries inherit this invariance.

2.1.1. Balanced Accuracy (Arithmetic Mean A of TPR and TNR)

It aggregates per-class sensitivities additively and equals 1 iff both class-conditional sensitivities are 1. Properties are developed in [

26]. By construction,

is invariant to

since it is a function of

only.

2.1.2. Youden’s (Informedness)

Introduced for diagnostic testing [

27],

is a linear rescaling of

and hence also prevalence-invariant. It measures the vertical distance of a ROC point from the no-skill diagonal [

9].

2.1.3. -Mean (Geometric Mean of TPR and TNR)

Widely used in imbalanced learning as a class-symmetric criterion that penalizes uneven performance [

15]. As a product of class-conditionals,

is independent of

.

2.1.4. -Mean (Harmonic Mean of TPR and TNR)

This metric is stricter than

and

under dispersion. It has been mainly adopted in biomedical applications [

28,

29,

30]. As a symmetric mean of

, it is prevalence-invariant.

2.1.5. The ROC Curve

For a score

thresholded at

t, the ROC locus is

with

. Both ROC and its area depend only on the pair of class-conditional score distributions and are therefore invariant to

[

9].

2.2. Prevalence-Sensitive (Class-Imbalance-Dependent) Measures

The following measures vary with even when are fixed; they mix class-conditional terms with priors or marginals.

2.2.1. Overall Accuracy

The decomposition

shows that accuracy conflates class prior and conditional performance, whereas

and

isolate sensitivity to positives and negatives, respectively. Thus, for fixed

, accuracy increases as the prior mass shifts toward the better-performing class [

14,

15].

2.2.2. Precision

Precision, also named Positive Predictive Value (PPV), is

, which by Bayes’ rule equals

explicitly dependent on

.

2.2.3. F1-Score

The

-score [

3,

4],

inherits the PPV dependence.

2.2.4. Precision-Recall Curve

Precision-recall (PR) curves and their area are likewise prevalence-sensitive [

11,

31]. As PR plots TPR against precision, and the latter depends on

, the area under the PR curve is sensitive to class imbalance.

2.2.5. Matthews Correlation Coefficient

In binary classification, outcomes are summarized by the

confusion matrix shown in

Table 1, where their elements are calculated in Equation (

1). The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) [

5] is defined as

It equals the Pearson correlation between predicted and true binary labels and takes values in

(1 for perfect prediction,

for total disagreement).

is not invariant to

: for fixed

the numerator and denominator scale differently with positives and negatives, i.e.,

, so

varies with

[

1].

2.2.6. Cohen’s

Let

be the observed agreement and

the chance agreement computed from the empirical marginals; then

In the binary case, if

is the prevalence and

the predicted positive rate, then

so both

and

depend on

(and on

). The prevalence paradox is the empirical fact that

can be low—even near zero—despite very high accuracy when classes are rare: as

moves away from

,

increases toward

, shrinking the numerator

[

6,

32]. Hence

is prevalence-sensitive.

2.3. Summary

In general, prevalence-insensitive measures (TPR, TNR,

-mean, J,

-mean,

-mean, ROC) quantify intrinsic discrimination independently of

, which is critical for comparing models across datasets with different priors. Prevalence-sensitive measures (accuracy, PPV, F

1, PR, MCC,

) remain essential for operational decision-making because they reflect the interaction between model behavior and base rates. However, under imbalance they must be interpreted jointly with class-conditional rates and priors [

15,

16] or complemented by a class-specific perspective [

33].

Prevalence-insensitive evaluation should be the default when reliability across classes matters. Metrics that mix class-conditional terms with class priors (e.g., accuracy and F1) can change merely because the class proportions change, even if the class-conditional behavior of the classifier does not. In contrast, indices constructed from true positive rates—binary TPR/TNR or, in the multiclass case, the vector of per–class TPRs—are invariant to prevalence by definition. Consequently, any symmetric summary of these components (e.g., the Pythagorean means of per-class TPRs: arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic) inherits prevalence-insensitivity, enabling fair comparisons across datasets and shifts in base rates.

3. The Pythagorean Means

The Pythagorean school, founded by Pythagoras of Samos (6th–5th century BCE), treated number and proportion as the underlying structure of reality. Its program linked arithmetic, geometry, and musical harmony. Within this tradition arose the triad of the so-called Pythagorean means—arithmetic (equality of increments), geometric (proportionality), and harmonic (reciprocity)—which later authors (e.g., Euclid, Nicomachus) formalized and transmitted.

Henceforth, we write A, G, and H for the arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic mean, respectively.

Let

and let

be weights with

.

In the unweighted case (

,

) these reduce to

All three means are symmetric and satisfy the chain of inequalities , with equality throughout if and only if .

While the Pythagoreans singled out the triad (A,G,H) for their distinct conceptual roles, later analysis unified them under the

power means (a.k.a. generalized means), defined for

by

so that

A,

G, and

H.

In general, the monotonicity property () yields . This perspective clarifies the structural position of the Pythagorean means as canonical representatives of the exponents within a continuous one-parameter family.

Beyond the three classical Pythagorean means, generalized families—such as the Kolmogorov–Nagumo–de Finetti quasi-arithmetic means (

Appendix A) and the Gini means (

Appendix B)—provide parametric lenses for analyzing monotonicity, convexity, and the comparative behavior of TPR/TNR aggregators. These families subsume the Pythagorean triad as special cases and enable principled trade-offs, while remaining prevalence-insensitive because they can be built exclusively from class-conditional quantities [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

4. Mean-Based Evaluation from TPR and TNR

Let and denote, respectively, the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the true negative rate (specificity) of a binary classifier. Any class-symmetric scalar summary based solely on is invariant to the class prior .

4.1. Arithmetic Mean

It aggregates sensitivity and specificity with equal weight and is widely used as a prevalence-robust alternative to overall accuracy [

9,

10].

For

,

a weighted arithmetic mean that reduces to

at

. The family

traces a line segment in the unit square connecting the axes-aligned extremes.

As an evaluation criterion it preserves the probabilistic semantics of class-conditional sensitivities and it is invariant to class-prior skews, thereby mitigating the dominance of the majority class in imbalanced settings. In binary classification it is a strictly proper scoring rule [

40] for the pair

, and it admits a principled uncertainty treatment, deriving exact posteriors and credible intervals under conjugate priors, and showing how to compare classifiers on finite samples without relying on asymptotics [

26]. In modern ML practice—particularly in imbalanced binary tasks such as anomaly/fraud detection, medical diagnosis, or cost-sensitive classification—balanced accuracy is routinely reported to reflect symmetric performance across the positive and negative strata, and it is often preferred when one wants an additive aggregation of

and

with transparent interpretation in terms of average per-class sensitivity.

4.2. Geometric Mean

A weighted variant uses exponents

:

Both and are strictly increasing in each argument on and equal 1 iff .

The geometric mean G is widely adopted in imbalanced-learning research because it heavily penalizes uneven performance: if either sensitivity or specificity is small, G collapses accordingly; conversely, it rewards classifiers that simultaneously maintain both rates high [

10,

41]. Comprehensive surveys on imbalanced data explicitly recommend G-mean as a robust, threshold-based indicator that captures the joint behavior of minority- and majority-class sensitivities without being biased by class priors [

15].

4.3. Harmonic Mean

with

, and define

at

by continuity. A weighted harmonic mean (emphasizing

versus

) is

which reduces to

at

and assigns more weight to

as

increases (and to

when

). While mathematically most conservative among the three classical means, the harmonic mean of

is notably less common in mainstream machine learning reporting than

-mean and

-mean. Contemporary surveys typically favor

or

for class-symmetric summaries [

10,

29], but

arises in scientific applications where one demands a symmetric and strongly conservative aggregation of

and

. In biomedical prediction,

has been explicitly adopted to evaluate classifiers under class imbalance, precisely because it treats both groups equally and punishes departures in either sensitivity or specificity.

Historically, one of the earliest explicit ML uses appears in medical informatics when developing predictors of diabetic nephropathy under irregular and imbalanced clinical data [

23], with subsequent adoption in traffic-safety Bayesian networks [

24,

42], genome-wide psoriasis susceptibility prediction [

25], seizure prediction [

28], neurodevelopmental EEG [

43], and clinical pharmacovigilance for QTc risk [

30], all defining or employing

as the harmonic mean of sensitivity and specificity to weight both error types equally and to deter degenerate single-class solutions under skew.

Methodologically,

is a symmetric, reciprocal aggregator that penalizes dispersion between class-conditional accuracies and remains prevalence-insensitive because it is built from within-class rates (TPR and TNR computed conditional on the true class). In multiclass settings, applying the same principle to the per-class sensitivities

yields a stringent scalar summary that typically penalizes dispersion more than the arithmetic or geometric mean; a detailed analysis is provided in

Section 6.

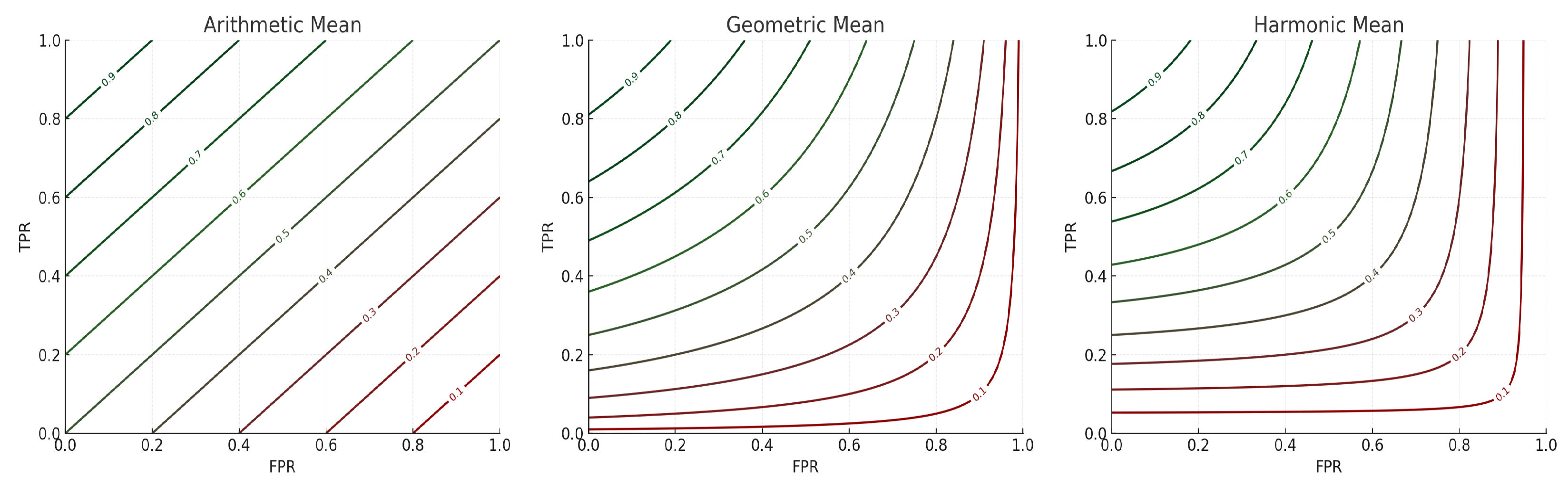

5. Geometric Characterization of A, G, and H Isocurves

Let

and

. For a fixed level

, the level sets (isocurves) of the three means in the

-plane are

Hence, A has straight isocurves (lines of slope ); has rectangular hyperbolas with asymptotes and ; and also yields rectangular hyperbolas but translated, with asymptotes and , and center at .

Equivalently, as shown in

Figure 1, in the

plane—similar to the ROC representation—where

, the same level

c takes the forms

In these -coordinates, isocurves are again lines (now of slope ); isocurves are rectangular hyperbolas with asymptotes and ; and isocurves are rectangular hyperbolas with asymptotes at and . Geometrically, admits linear trade-offs along straight indifference lines; enforces multiplicative balance () that pulls level sets toward the axes; and is the most stringent, with value-dependent asymptotes that require each coordinate to exceed to attain level c.

6. Harmonic Mean of Per-Class Sensitivity

In the binary case, the harmonic mean of sensitivity and specificity, has been used—albeit sparingly—in ML as a symmetric, prevalence-insensitive trade-off between the true positive rate and the true negative rate. In the multiclass setting, this extends naturally by taking the harmonic mean of the per-class sensitivities. Let

denote the true positive rate of class

k for

; then

To illustrate how an imbalanced class distribution can distort overall performance while masking weak per-class behavior, consider a four-class problem with supports

,

,

,

(total

). This yields prevalences

, a long-tailed pattern typical of safety-critical multiclass tasks in which some classes—though equally important—are rare. We will compare the standard metrics with class-symmetric summaries (arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic means of the per-class sensitivities). If misclassifications concentrate in the minority class

D, the standard metrics remain dominated by the frequent classes

A–

C and can appear deceptively high, whereas the means—especially the harmonic mean—drop to reflect the poor recall of

D. With this in mind, take the following confusion matrix (rows = true classes, columns = predicted classes):

For this

confusion matrix, the classical performance scores are numerically high—accuracy = 0.958,

, weighted-

, multiclass Matthews Correlation Coefficient

[

44,

45], and Cohen’s

. Yet these aggregates conceal a severe weakness: class

D has

(many false negatives). This happens because averaging and global agreement/correlation summaries allow substantial compensation across classes, so high overall scores can coexist with an underrepresented minority.

Per-class sensitivity (true positive rates) are

The three Pythagorean means over

:

Thus, while and may remain high, can drop sharply—correctly signaling that at least one class has very low sensitivity. This behavior is structural: (i) is prevalence-insensitive because it aggregates within-class recalls; (ii) it is strictly more stringent than and (, with equality only when all are equal); (iii) it penalizes dispersion by Schur-concavity (any increase in inter-class inequality lowers ); and (iv) it is quantitatively constrained by underperforming classes (Proposition 1).

Proposition 1 (Bounds for the harmonic mean of per-class TPRs). Let be the per-class sensitivities and and . Then:

- 1.

Universal bounds.with equality on either side if and only if . - 2.

Upper bound with m weak classes. Assume at least m classes satisfy with , and that for all classes. Thenand the first inequality is attained at the extremal vector .

Proof. (1) Since

and

is decreasing on

, we have

. Summing over

k yields

Equality on either side forces all to be equal, and conversely.

(2) For the

m weak classes,

implies

; for the remaining

classes, the global ceiling

implies

. Therefore

To prove that this upper bound is itself

, observe

which holds because

. □

Proposition 1 formalizes the nature of the harmonic mean when it aggregates class-conditional true-positive rates. Geometrically, along harmonic-mean isocurves in the binary case, achieving any target level requires both sensitivity and specificity to be sufficiently far from zero; a very low value on one axis cannot be offset by arbitrarily increasing the other. In the multiclass setting, the same principle holds: a subset of classes with low sensitivity constrains the overall harmonic mean, regardless of how well the remaining classes perform. This is precisely the behavior sought in safety-critical evaluation: the score remains conservative unless every class is adequately detected, preventing high aggregate numbers from obscuring poorly served classes.

The upper bound for entails two practical consequences: (a) monotonicity: strengthening the weak class or improving the best classes can raise the attainable value of H, whereas adding more weak classes lowers it); (b) meeting a target : e.g., with , , , and , the critical , which means that a single class with TPR forces , regardless of how well the other 34 classes perform.

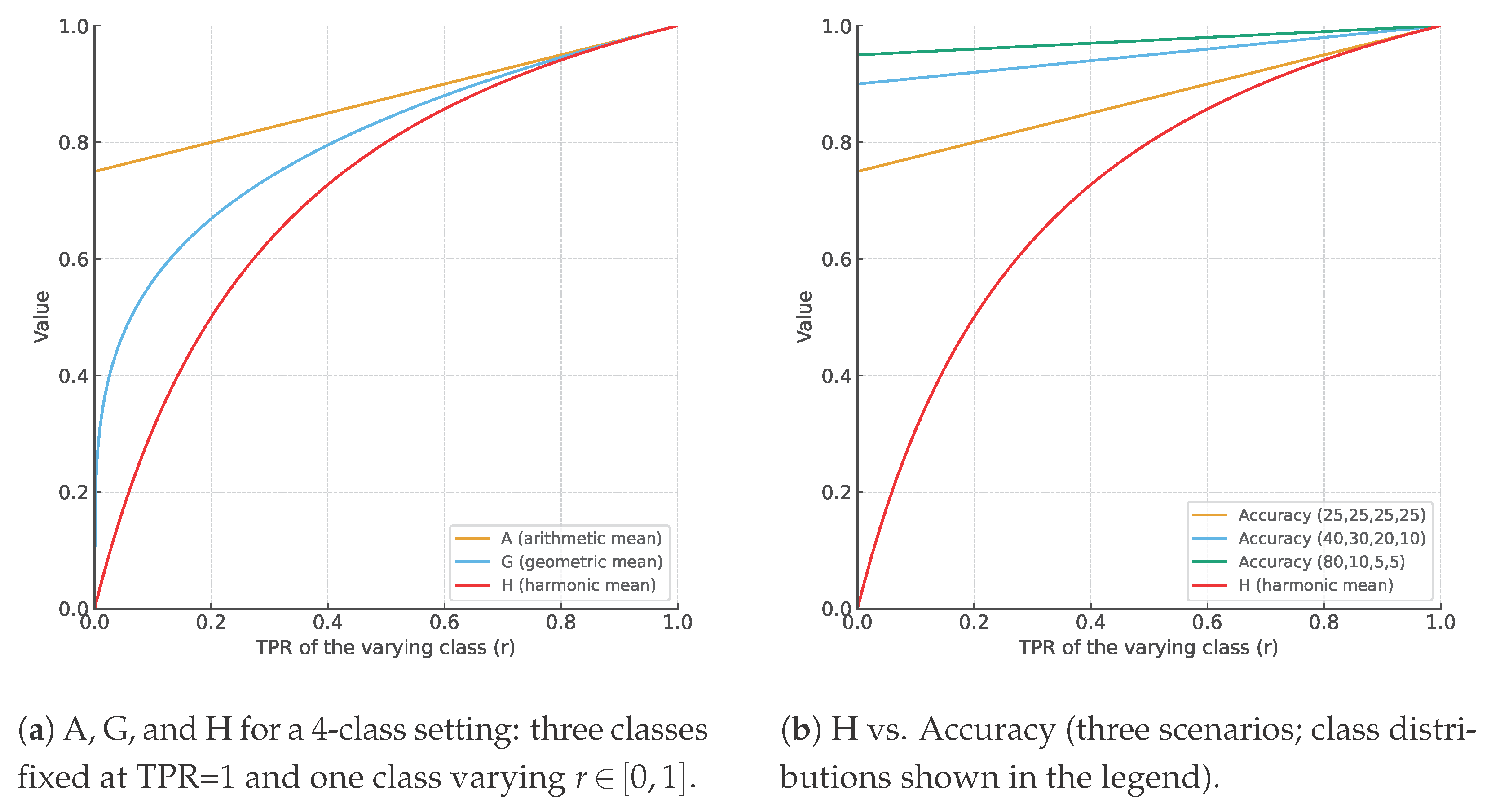

Figure 2a illustrates Proposition 1 in a stylized four-class scenario (three classes at

, one varying). The curve

coincides with the upper bound (with

,

,

), while

and

lie strictly above it for

. The implication is explicit: even when most classes are perfect, a single weak class bounds

from above and induces a concave, saturating response. Hence, while A and G remain comparatively optimistic,

exposes—and quantitatively constrains—rare-class underperformance, which is decisive in safety-critical evaluation.

Section 7.2 analyzes a multiclass cancer dataset in which a few low-sensitivity tumor types exert a substantial influence on

, producing a pronounced gap with global metrics (e.g., accuracy,

) and making the rare-class deficits explicit.

Figure 2b plots Accuracy as a function of the varying class: three classes have perfect sensitivity

, and the remaining (varying) class has

. Denote by

the prevalence of the varying class and by

the total prevalence of the three perfect classes. Accuracy depends linearly on

r:

, so the slope equals

and the intercept at

is

. Thus, for

the slope is

, for

it is

, and for

it is

. As the class becomes rarer, the line flattens and Accuracy becomes largely insensitive to

r; even poor sensitivity of the rare class barely changes the overall score. This linearity follows directly from the class-wise decomposition

and does not depend on how errors are distributed among the other classes. The

curve (red, identical to panel (a)) shows the opposite behavior: it penalizes small

r strongly, making rare-class underperformance visible that Accuracy may mask.

The harmonic mean offers two practical advantages over and in safety-critical evaluation. First, it is non-compensatory: a single weak class exerts decisive influence, so high scores are impossible unless every class attains adequate sensitivity. Second, it is the most conservative of the Pythagorean means, providing a stable, prevalence-insensitive summary that aligns with worst-class reliability requirements. By contrast, and are progressively more permissive, allowing strong performance on frequent or easy classes to offset weaknesses elsewhere. Therefore, may be not preferable when stakeholders explicitly accept compensatory trade-offs (e.g., screening pipelines where aggregate throughput is prioritized), or when some classes have very scarce/noisy labels, where strong penalty near zero can overreact to estimation noise; in such cases or provide smoother summaries consistent with the application goals. However, if is set aside for either reason, the choice should be explicit and well-justified, as it means accepting either compensatory masking of weak classes or reduced protection against rare-class failures—trade-offs with significant consequences in safety-critical settings.

Section 6 formalized the harmonic mean

as a prevalence-insensitive, class-symmetric aggregator of per-class true-positive rates and established that it is the most conservative of the Pythagorean means; in particular, Proposition 1 proves that even a small set of weak classes places a hard upper bound on

, while

and

can remain comparatively high. Building on these theoretical considerations,

Section 7 empirically validates the corresponding claims.

7. Experimental Analysis

The experimental analysis is designed to evaluate the benefits of using the Pythagorean means of true positive rates compared to the standard, commonly used classification performance measures, and to analyze the contribution of the particular behavior of the harmonic mean.

As a baseline classifier, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm [

46] was chosen because it is an ensemble method rather than a simple model, typically achieves good results (highly competitive), is computationally efficient (built on fast decision trees), and can be considered a black-box model—similar to deep learning approaches, though without large-scale parameterization. Concretely, the settings were: n_estimators = 100 (number of trees); max_depth = None (unbounded); criterion = “gini”; max_features = “sqrt”; bootstrap = True; min_samples_split = 2; min_samples_leaf = 1; class_weight = None; random_state = 0. These are the library defaults; no hyperparameter tuning or resampling was performed. However, the choice of classifier is purely illustrative, i.e., the experiments are model-agnostic, allowing readers to apply any classifier.

All experiments were carried out with stratified 10-fold cross-validation. We evaluated two multiclass performance measures: accuracy and the area under the MCP (Multi-class Classification Performance) curve [

18,

47]. The MCP curve is computed directly from the class probabilities output by the classifier—analogous to the ROC curve in the binary case—and, unlike accuracy, its area reflects the probabilistic nature of the predictions [

48].

7.1. UCI Datasets

The study involves 18 datasets from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [

49], varying in the number of samples (150 to 19,020), number of variables (4 to 166), and number of classes (2 to 11) (see

Table 2).

Across the 18 UCI datasets, accuracy exceeds the harmonic mean of per-class sensitivities by a modest margin on average (mean row: vs. , , ≈2.7% relative to ), but the gap is highly dataset-dependent. On several skewed or multiclass problems the difference is pronounced: cardiotocography_morphologic shows vs. (absolute , relative), vertebral_column vs. (, ), customer_churn vs. (, ), landsat_satellite vs. (, ), and musk_v2 vs. (, ). These are precisely the settings where per-class sensitivities are uneven: , with dropping most when some classes are weak, while remains buoyed by majority classes. By contrast, on nearly balanced/easy tasks—e.g., rice_cammeo_osmancik, data_banknote_authentication, divorce, phishing_websites, or the classic iris—all three means nearly coincide with accuracy, indicating limited dispersion across per-class recalls.

The last row highlights a striking contrast between class-label summaries and the probability-based MCP: the mean MCP is , substantially below (), (), and (). This systematic drop reflects that MCP assesses the full probability vectors, not just the final class labels; consequently it is sensitive to weak margins or miscalibration even when and look high. The effect is pronounced on vowel (11 classes): but , revealing limited probability separation despite excellent label accuracy. Similar patterns appear in musk_v1 ( vs. for labels, ), sonar ( vs. , ), and heart ( vs. , ). Overall, the mean row (– vs. ) supports a dual recommendation: use to guard against rare-class underperformance in label space, and report MCP to capture probability-level quality. Together they reduce optimism from prevalence-sensitive aggregates and expose weaknesses that accuracy alone can obscure.

7.2. Case Study: Predicting 35 Cancer Types

To illustrate the effect of imbalance in multiclass settings, we adopt the cancer prediction dataset of Nguyen et al. [

50]. That study applies machine learning to infer the tumor tissue of origin in advanced-stage metastatic cases—a clinically critical task because a substantial subset of patients lack definitive histopathologic diagnoses and, since therapy choices depend on the primary site, face limited treatment options. The source compendium aggregates multiple molecular assays and initially provides 4131 features designed to discriminate 35 cancer types based on driver/passenger status and simple/complex mutation patterns. It contains 6756 samples drawn from the Hartwig Medical Foundation (metastatic tumors) and the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes consortium (primary tumors). The authors then perform univariate feature selection to retain 463 variables and derive 48 additional regional mutational-density features via nonnegative matrix factorization, yielding the version used here: 6756 samples, 511 predictors, and a 35-class target (biliary, breast, cervix, liver, pancreas, thyroid, etc.).

The multiclass nature of the task makes some binary measures (e.g., ROC) less standardized, since several non-equivalent generalizations exist (one-vs-rest, one-vs-one, macro/micro AUC, volume under the ROC surface). We therefore emphasize prevalence-insensitive, class-conditional summaries and the MCP curve. The class distribution is markedly imbalanced: among 35 tumor types,

Breast has 996 samples (14.7%) while

Skin_Carcinoma has 25 (0.4%), a ∼40:1 frequency ratio. Such skew can make overall accuracy appear high while concealing weak per-class sensitivities, underscoring the need for metrics that reflect class-wise performance (class-independent vs. class-specific perspective [

33]).

On this high-dimensional, many-class dataset, global agreement indices are high (, Cohen’s ), indicating that most predictions match the true labels and that agreement remains strong even after correcting for chance under a large label space. However, the prevalence-insensitive, aggregated means of the per-class true positive rates reveal substantial heterogeneity across classes: the arithmetic mean is , the geometric mean , and the harmonic mean , with the strict ordering . The large gap between and (about ) signals marked dispersion in class sensitivities: the harmonic mean is disproportionately penalized by low per-class sensitivities, so even a small subset of under-served classes (with very low TPR) can depress while leaving Accuracy and relatively unaffected if those classes are rare. In fact, the value of is about 38% higher than the value of , what reveals that it is extremely important to analyze the class-specific behavior of a system that tries to make predictions on specific tumor classes.

Consistently, the area under the MCP curve is moderate (

), indicating limited operating-point configurations that achieve uniformly high per-class sensitivity; this aligns with the low

, which diagnose a long tail of weak classes. The larger the area under the MCP curve, the lower the uncertainty of the predictive system. The MCP curve for this multiclass dataset (see Figure 6 in [

47]) reveals that probabilistic measures are also aligned with

—and they can be even stricter—at highlighting poor per-class behavior of the diagnostic system, which might be dramatic in medical realms.

Therefore, what appeared to be a sound diagnostic system () may not be so reliable (H and AU(MCP) ). In sum, while overall agreement is strong, the prevalence-insensitive summaries—especially the harmonic mean—expose uneven class-wise performance that would be obscured by prevalence-sensitive measures, such as Accuracy or Cohen’s .

8. Conclusions

This work clarifies why widely used global indices—accuracy, F

1-score, Cohen’s

, MCC—are intrinsically prevalence-sensitive and can therefore distort performance assessment under class imbalance. We formalized this dependence, advocated prevalence-insensitive evaluation built solely from class-conditional rates, and analyzed the arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic means as class-symmetric aggregators, including a geometric account of their isocurves and stringency. Beyond well-known monotonicity

, we established bounds that clarify when

must decrease and by how much: Proposition 1 quantifies the impact of

m weak classes and yields actionable constraints. The complementary visual analyses (

Figure 2) make these effects explicit: while Accuracy may remain almost flat when the weak class is rare,

reacts strongly to small per-class sensitivities. Together, these results supply a coherent toolbox for risk-aware evaluation in safety-critical diagnosis.

Empirically, the UCI study shows that the mean gap between Accuracy and is modest on average but can be substantial on skewed datasets, confirming that prevalence-sensitive aggregates may overstate performance. The cancer case study further demonstrates that high global agreement can coexist with widely dispersed per-class sensitivities, where exposes rare-class deficits that Accuracy, , or MCC may mask. Probability-based MCP complements these label-level summaries by reflecting separation in predictive probabilities, revealing weaknesses even when label metrics look strong.

In general, reliance on global prevalence-sensitive measures can overstate safety precisely where failures are most consequential—rare classes—thereby inflating confidence and masking operational risk. Prevalence-insensitive, class-symmetric means—particularly the harmonic mean of per-class sensitivity—provide conservative, comparable summaries that better track real diagnostic risk.

The theory naturally extends along two axes: (a) families of means (Gini, Kolmogorov–Nagumo–de Finetti, Lehmer, Stolarsky), enabling principled control of sensitivity to dispersion while remaining prevalence-insensitive; (b) majorization tools (Schur-convexity, T-transforms, Karamata) to sharpen guarantees under distributional shifts of . These future work directions aim at evaluation that remains reliable when rare classes matter most.