AGF-HAM: Adaptive Gated Fusion Hierarchical Attention Model for Explainable Sentiment Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Aspect-aware embedding fusion: Instead of naive concatenation, embeddings from Transformer models (BERT, RoBERTa) are fused using an attention-based fusion mechanism, enabling the model to adaptively weight different sources based on aspect relevance.

- Sequential modeling via BiLSTM: To capture both forward and backward dependencies in text, the aspect-aware fused embeddings are passed through a BiLSTM encoder, enriching the representation with contextual dynamics.

- Hierarchical + Position-aware attention: A multi-level attention block is introduced. Word-level attention highlights aspect-relevant tokens; an optional sentence/aspect aggregation level combines across multiple aspects. Position weighting ensures tokens closer to the aspect term receive higher importance—following inspirations from recent position-aware attention models [10,11].

- Interpretable classification: The final representation feeds into a classification layer with dropout and regularization. The model enables visualization of attention heatmaps (word + aspect level) and examination of positional weights to provide transparency in prediction.

- A hybrid ABSA model with attention-based fusion of Transformer embeddings and explicit aspect embedding, enabling aspect sensitivity in representation.

- The design and implementation of a hierarchical + position-aware attention module, capturing both local (word-level) and hierarchical (aspect-oriented) sentiment cues, with positional bias toward aspect proximity.

- A newly collected, balanced ABSA dataset of 10,000 reviews uniformly labeled across five sentiment classes, addressing limitations of outdated or skewed datasets.

- Extensive evaluation on both the custom dataset and public ABSA benchmarks (e.g., Amazon reviews), showing improvements in accuracy, interpretability, and robustness.

- Detailed interpretability analysis: visualizing attention weights, position weight curves, and aspect-level influence to better understand model decisions.

- Design an attention-based fusion mechanism to combine Transformer embeddings (BERT, RoBERTa) with an explicit aspect embedding in a context-sensitive manner.

- Employ BiLSTM to model sequential context forward and backward, enhancing the representation of aspect-aware fused embeddings.

- Build a hierarchical + position-aware attention module that assigns word-level attention conditioned on aspect, aggregates across aspects or sentences, and reweights tokens based on proximity to the aspect.

- Construct and release a new balanced dataset of 10,000 product/service reviews, each labeled across five sentiment classes, to provide a modern benchmark for ABSA research.

- Conduct rigorous experiments on both the new dataset and established benchmark datasets to validate performance, generalization, and interpretability.

- Provide interpretability tools: attention heatmaps, position weight visualization, and aspect-level influence to help users and researchers understand model outputs.

2. Related Work

2.1. Machine-Learning (Traditional) Methods

2.2. Deep-Learning Methods

2.3. Features Level and Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA) Methods

2.4. Attention and Hierarchical Attention Mechanism

2.5. Transformer-Based Models

2.6. Explainable and Interpretable Models

3. Materials and Methods

| Algorithm 1 HAM-X—Hybrid Attention-based Model with Explainability Layer |

|

3.1. Input Layer

3.2. Preprocessing and Tokenization

3.3. Aspect Extraction

3.4. Token and Position Embeddings

3.5. Linear Projection

- It is assumed that all embeddings are in the same semantic space of dimension d.

- The representations are then comparable directly and can be successfully fused in the next Gated Fusion Layer.

- All unnecessary differences between models BERT vs RoBERTa are averaged, and complementary features are kept.

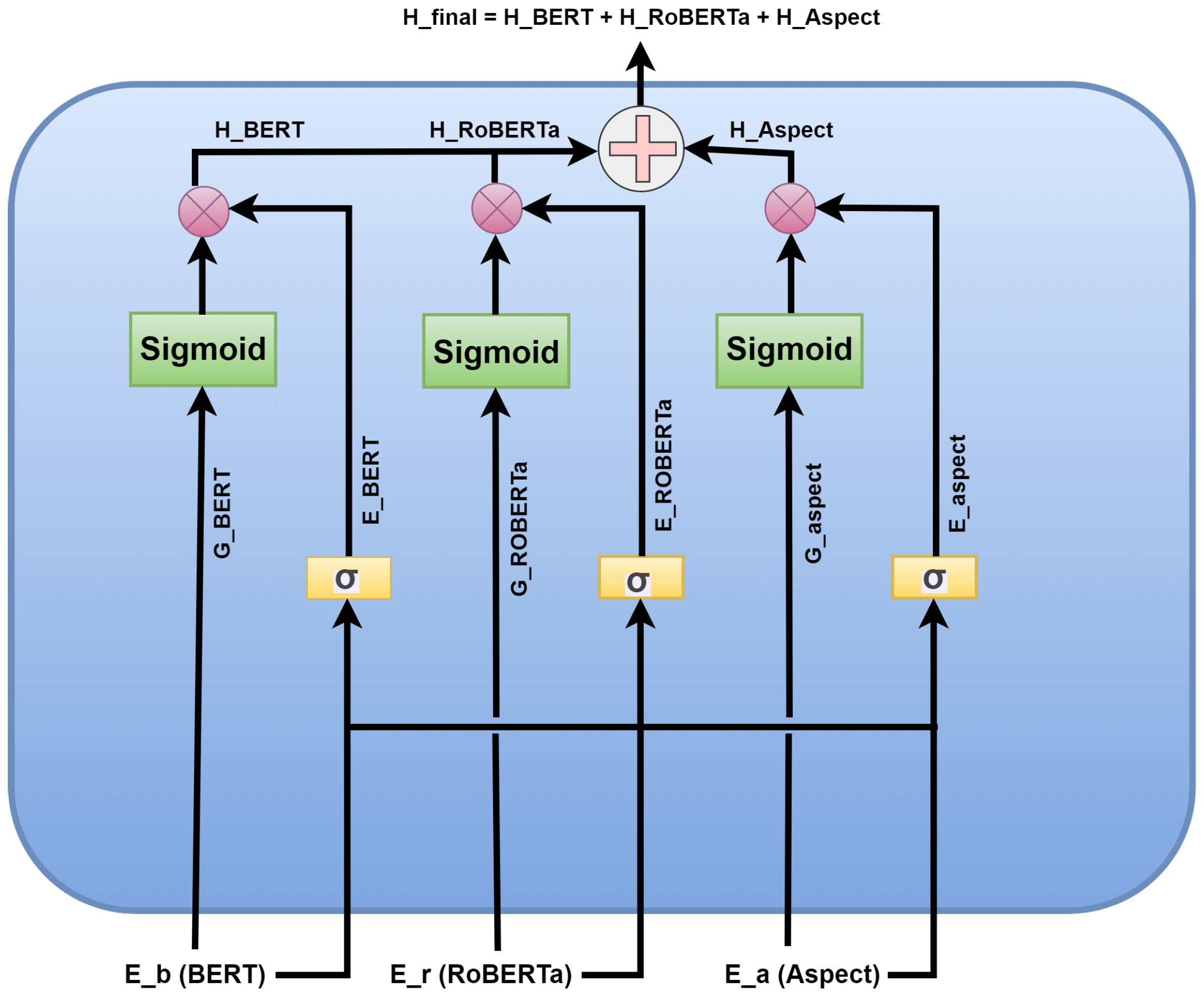

3.6. Gated Fusion Layer

- Adaptive weighting: The model is trained to apply BERT or RoBERTa features based on the token and context.

- Aspect-conscious integration: The fusion is still biased towards the opinion target but not generic sentiment by incorporating the aspect embedding in the gating function.

- Redundancy minimization: Gating filters rather than concatenating both embeddings results in redundancy minimization.

- Interpretability: Gating scores are visualizable to learn which model had a more significant impact on a decision of a particular token.

3.7. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM)

- Sequential reasoning: Reasoning between opinion words at different distances, for example “not good”.

- Aspect alignment: The model captures the aspect-conditioned sentiment by learning a contextual flow around the aspect that involves the aspect preceding context and the aspect succeeding context.

- Complementary to transformers: Transformers are more effective at contextualizing on a global scale, whereas BiLSTM strengthens local, position-sensitive dependencies, which prove particularly useful in aspect-based tasks.

3.8. Hierarchical Attention Mechanism (HAM)

3.8.1. Word-Level Attention

3.8.2. Position-Level Attention

3.8.3. Aspect-Level Attention

3.8.4. Final Hierarchical Attention Representation

3.9. Final Classification and Optimization

3.9.1. Linear Projection and Softmax Classification

3.9.2. Regularization and Focal Loss Optimization

- is the weighting factor for class ,

- is the focusing parameter controlling difficulty emphasis,

- is the predicted probability for the true class.

3.9.3. Training Strategy

3.10. Explainability Module

3.10.1. Attention Headmaps

3.10.2. Aspect-Level Explanation

3.10.3. SHAP/Integrated Gradients

- Detected Aspect: phone/performance

- Opinion Tokens: awful, slow, crashes, useless

- Aspect-Sentiment Score:

- Aspect Polarity Label: Very Negative

The model classifies this sentence as Very Negative. Attention, Aspect-level Polarity, and SHAP/IG all emphasize the same tokens: awful, useless, and crashes—indicating they are the strongest contributors to the negative sentiment toward the phone’s performance.

4. Dataset Description and Hypermeters

4.1. Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews

4.2. GoEmotions (5-Class Variant)

4.3. Summary of Datasets

4.4. HyperMeters

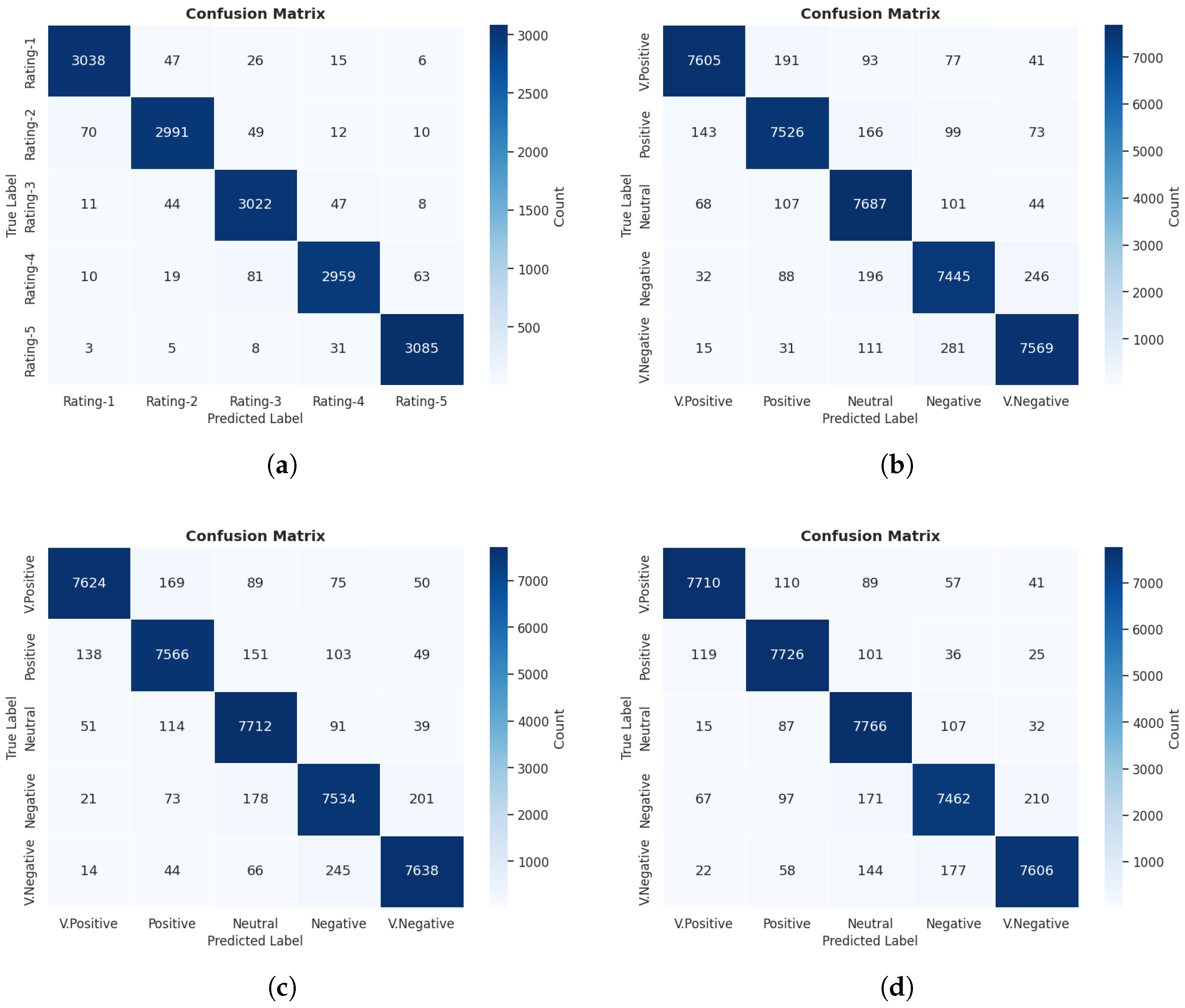

5. Experiments and Results Discussions

5.1. Ablation Study

5.2. Comparative Study

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, A.; Cambria, E.; Schuller, B.; Howard, N.; Poria, S.; Huang, G.-B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Toh, K.-A.; Wang, Z.; et al. A semi-supervised approach to Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis. Cogn. Comput. 2018, 10, 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.; Khan, I.; Alharbi, A.; Alshammari, M.; Alshammari, T.; Ahmad, M. Unifying Sentiment Analysis with Large Language Models: A Survey. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103651. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, I.; Cambria, E.; Welsch, R. Bayesian neural networks for aspect-based sentiment analysis. Cogn. Comput. 2018, 10, 766–777. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, O.; Goldberg, Y. Neural word embedding as implicit matrix factorization. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Liu, K.; He, S.; Zhao, J. How to generate a good word embedding. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2016, 31, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luong, T.; Jurafsky, D.; Hovy, E. Inferring sentiment with social attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ACL, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, N.; Majumder, P.; Ekbal, A. Recent trends in deep learning based sentiment analysis. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 1180–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1 (long and short papers), pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, A. Hierarchical attention based position-aware network for aspect-level sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–1 November 2018; pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Madasu, A.; Rao, V.A. A position aware decay weighted network for aspect based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applications of Natural Language to Information Systems, Helsinki, Finland, 24–26 June 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z. Fine-tune BERT with sparse self-attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 3548–3553. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Gao, J.; Ren, X.; Xu, H.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Kwok, J.T.Y. Sparsebert: Rethinking the importance analysis in self-attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 9547–9557. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.M. Does machine learning really work? AI Mag. 1997, 18, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Lee, L. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found. Trends® Inf. Retr. 2008, 2, 1–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, A.I. Opinion mining on US Airline Twitter data using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Computer Engineering Conference (ICENCO), Cairo, Egypt, 29–30 December 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, A.; Agrawal, A.; Rath, S.K. Classification of sentiment reviews using n-gram machine learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 57, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouloumpis, E.; Wilson, T.; Moore, J. Twitter sentiment analysis: The good the bad and the omg! In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Barcelona, Spain, 17–21 July 2011; Volume 5, pp. 538–541. [Google Scholar]

- Amjad, A.; Khan, L.; Chang, H.T. Effect on speech emotion classification of a feature selection approach using a convolutional neural network. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amjad, A.; Khan, L.; Chang, H.T. Semi-natural and spontaneous speech recognition using deep neural networks with hybrid features unification. Processes 2021, 9, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1408.5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Amjad, A.; Afaq, K.M.; Chang, H.T. Deep sentiment analysis using CNN-LSTM architecture of English and Roman Urdu text shared in social media. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Amjad, A.; Ashraf, N.; Chang, H.T.; Gelbukh, A. Urdu sentiment analysis with deep learning methods. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 97803–97812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Amjad, A.; Ashraf, N.; Chang, H.T. Multi-class sentiment analysis of urdu text using multilingual BERT. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N.; Khan, L.; Butt, S.; Chang, H.T.; Sidorov, G.; Gelbukh, A. Multi-label emotion classification of Urdu tweets. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Qazi, A.; Chang, H.T.; Alhajlah, M.; Mahmood, A. Empowering Urdu sentiment analysis: An attention-based stacked CNN-Bi-LSTM DNN with multilingual BERT. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, L. Attention-based LSTM for aspect-level sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Austin, TX, USA, 1–5 November 2016; pp. 606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms-a review. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2020, 9, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G.; Keogh, E.; Miikkulainen, R. Naïve Bayes. In Encyclopedia of Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 15, pp. 713–714. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, W.S. What is a support vector machine? Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1565–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Beresford, R. Basic concepts of artificial neural network (ANN) modeling and its application in pharmaceutical research. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2000, 22, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, R.; Jayasree, M. Aspect based sentiment analysis using support vector machine classifier. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Mysore, India, 22–25 August 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1581–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Hong, K.; Tsujii, J.; Chang, E.I.C. Feature engineering combined with machine learning and rule-based methods for structured information extraction from narrative clinical discharge summaries. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012, 19, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A survey of convolutional neural networks: Analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, G.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X. A unified position-aware convolutional neural network for aspect based sentiment analysis. Neurocomputing 2021, 450, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontiki, M.; Galanis, D.; Papageorgiou, H.; Androutsopoulos, I.; Manandhar, S.; Al-Smadi, M.; Al-Ayyoub, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, B.; De Clercq, O.; et al. Semeval-2016 task 5: Aspect based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2016; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, L.; Xu, R.; Ao, X.; Yang, M. A challenge dataset and effective models for aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 6280–6285. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Tan, C.; Tang, D.; Zhou, M.; Xu, K. Adaptive recursive neural network for target-dependent twitter sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Baltimore, MD, USA, 22–27 June 2014; Volume 2: Short Papers. pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Koroteev, M.V. BERT: A review of applications in natural language processing and understanding. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, V.; Gokaslan, A. OpenGPT-2: Open language models and implications of generated text. XRDS Crossroads Acm Mag. Stud. 2020, 27, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, R. GPT-3: What’s it good for? Nat. Lang. Eng. 2021, 27, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumakov, S.; Kovantsev, A.; Surikov, A. Generative approach to aspect based sentiment analysis with GPT language models. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 229, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Shu, L.; Yu, P.S. BERT post-training for review reading comprehension and aspect-based sentiment analysis. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.02232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Bing, L.; Lam, W. Towards Generative Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Bing, L.; Lam, W. A survey on aspect-based sentiment analysis: Tasks, methods, and challenges. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 11019–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. BATAE-GRU: Attention-based aspect sentiment analysis model. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Symposium on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 5–7 February 2021; pp. 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghari, H.; Aghdam, M.H.; Emami, H. HAN: Hierarchical Attention Network for Learning Latent Context-Aware User Preferences With Attribute Awareness. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 49030–49049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; O’Hare, N.; Chang, Y.; Li, B. Hierarchical attention network for action recognition in videos. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, D. Multi-grained attention network for aspect-level sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 3433–3442. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Interactive attention networks for aspect-level sentiment classification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.00893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Han, P.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, E.; Wang, W. Transformer based multi-grained attention network for aspect-based sentiment analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 211152–211163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Khan, L.; Chang, H.T. Evolving techniques in sentiment analysis: A comprehensive review. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Rossi, L.; Prati, A. Adversarial training for aspect-based sentiment analysis with bert. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 8797–8803. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, A.; Sharma, A.; Mohana, R. An Enhanced Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis Model Based on RoBERTa for Text Sentiment Analysis. Informatica 2025, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Khan, L.; Choi, A. RAMHA: A Hybrid Social Text-Based Transformer with Adapter for Mental Health Emotion Classification. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Chen, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.11942. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.R.; Le, Q.V. Xlnet: Generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Perikos, I.; Diamantopoulos, A. Explainable aspect-based sentiment analysis using transformer models. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahin, M.A.; Shovon, M.S.H.; Mridha, M.; Islam, M.R.; Watanobe, Y. A hybrid transformer and attention based recurrent neural network for robust and interpretable sentiment analysis of tweets. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thogesan, T.; Nugaliyadde, A.; Wong, K.W. Integration of explainable ai techniques with large language models for enhanced interpretability for sentiment analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.11948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.K.; Darr, M.J. Interpretable AI for Time-Series: Multi-Model Heatmap Fusion with Global Attention and NLP-Generated Explanations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.00234. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.; Brahma, D.; Rai, P.; Modi, A. Fine-grained emotion prediction by modeling emotion definitions. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), Nara, Japan, 28 September–1 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Jing, Z.; Su, Y.; Han, Y. Large language models on fine-grained emotion detection dataset with data augmentation and transfer learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.06108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Trabelsi, A.; Qin, X.; Farruque, N.; Mou, L.; Zaiane, O.R. Seq2Emo: A sequence to multi-label emotion classification model. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 4717–4724. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, N.; Miao, D.; Chen, Q. Dual-channel and multi-granularity gated graph attention network for aspect-based sentiment analysis. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 13145–13157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.; Cai, J.; Gao, Z.; Li, X. Aspect-level sentiment classification with fused local and global context. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitoula, R.S.; Pramanik, M.; Panigrahi, R. Fine-Grained Classification for Emotion Detection Using Advanced Neural Models and GoEmotions Dataset. J. Soft Comput. Data Min. 2024, 5, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, A.; Sharma, A.; Chettri, S. Machine learning based sentiment analysis for text messages. Int. J. Comput. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Task/Model | Dataset(s) | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pang & Lee (2008) [17] | Opinion mining survey | IMDb, Amazon | Seminal survey establishing sentiment analysis foundations. |

| Tripathy et al. (2016) [20] | ML classifiers (SVM, NB) | IMDb, Amazon | Compared classical ML models for sentiment classification. |

| Kouloumpis et al. (2011) [21] | Twitter sentiment | Twitter Corpus | Showed impact of hashtags, POS, and n-grams on tweet sentiment. |

| Kim (2014) [24] | CNN for sentences | SST, Reviews | Introduced CNN as a strong baseline for sentiment tasks. |

| Bahdanau et al. (2014) [31] | Attention mechanism | WMT | Introduced attention—core component of modern ABSA. |

| Wang et al. (2016) [32] | ATAE-LSTM (ABSA) | SemEval-2014 | Classic ABSA model combining aspect vectors + attention. |

| Pontiki et al. (2016) [42] | ABSA benchmarks | SemEval-2014/2015/2016 | Defined standard datasets for ABSA tasks. |

| Jiang et al. (2019) [43] | MAMS (multi-aspect) | MAMS | Multi-aspect, multi-sentiment dataset for fine-grained ABSA. |

| Xu et al. (2019) [49] | BERT-PT for ABSA | SemEval-2014 | Post-trained BERT improves ABSA accuracy significantly. |

| Zhang et al. (2021) [50] | Generative ABSA | SemEval-2014 | Unified generative model for aspect extraction + sentiment. |

| Karimi et al. (2021) [59] | Adversarial BERT | SemEval-2014 | Improved robustness of ABSA models via adversarial training. |

| Chauhan et al. (2025) [60] | Enhanced RoBERTa | SemEval-2014 | Achieved SOTA (92.35%) using optimized RoBERTa. |

| Token | Attention Weight () | Aspect Polarity () | SHAP Value | Integrated Gradients (IG) | Combined Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| phone | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| is | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| awful | 0.91 | −1.00 | −0.82 | −0.90 | 0.88 |

| slow | 0.86 | −0.80 | −0.70 | −0.76 | 0.77 |

| crashes | 0.90 | −0.90 | −0.75 | −0.85 | 0.83 |

| often | 0.73 | −0.20 | −0.30 | −0.25 | 0.42 |

| today | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| useless | 0.94 | −1.00 | −0.88 | −0.92 | 0.91 |

| Column | Meaning/Source | Computation/Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Attention Weight () | From Hierarchical Attention Layer; shows focus strength per token. | |

| Aspect-Level Polarity () | Lexical or contextual sentiment value assigned to each token related to an aspect. | |

| SHAP Value | Measures a token’s contribution to model output relative to baseline input. | |

| Integrated Gradients (IG) | Captures gradient-based causal influence of each token embedding. | |

| Combined Importance | Averaged normalized influence from Attention, SHAP, and IG for final interpretability. |

| Sentiment Class | Mapped GoEmotions Labels |

|---|---|

| Very Positive | admiration, amusement, approval, joy, optimism, pride, love, desire, excitement |

| Positive | gratitude, relief, curiosity, caring, realization, surprise (positive context) |

| Neutral | neutral, confusion (ambiguous), surprise (neutral context), contemplation |

| Negative | disappointment, fear, nervousness, embarrassment, remorse, disapproval |

| Very Negative | anger, disgust, sadness, grief, annoyance, disappointment (strong) |

| Dataset | Domain | Samples | Sentiment Classes | Aspect Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Cell Phones | Product Reviews | 67,986 | 5 | Yes (Automatic + Rule-Based) |

| GoEmotions (5-Class) | Reddit Comments | 70,226 | 27 | No (Emotion-Oriented Labels) |

| Parameter | Symbol/Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | Step size for Adam optimizer controlling parameter updates | |

| Batch Size | Number of samples processed in each iteration | |

| Epochs | Maximum number of complete passes through the training data | |

| Optimizer | Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation for gradient-based optimization |

| Dropout Rate | Probability of randomly deactivating neurons to prevent overfitting | |

| Embedding Dimension | Dimensionality of BERT/RoBERTa and aspect embeddings | |

| BiLSTM Hidden Size | Number of hidden units in each BiLSTM direction | |

| Attention Heads | Number of heads in hierarchical attention computation | |

| Focal Loss | Focusing parameter emphasizing hard-to-classify samples | |

| Class Weight | Adaptive per class | Balances impact of class imbalance in focal loss |

| Max Sequence Length | Maximum token length of each input sequence | |

| Warmup Ratio | Fraction of training steps for linear learning rate warmup | |

| Early Stopping Patience | Stops training if no improvement in validation loss for p epochs |

| Model | GoEmotions-1 | GoEmotions-2 | GoEmotions-3 | Amazon Cell Phones | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | |

| SVM | 76.8 | 75.2 | 74.6 | 74.9 | 77.4 | 76.1 | 75.8 | 75.9 | 78.2 | 76.9 | 76.4 | 76.6 | 80.1 | 78.8 | 79.0 | 78.9 |

| LR | 77.5 | 76.3 | 75.7 | 75.9 | 78.1 | 77.0 | 76.6 | 76.8 | 78.6 | 77.3 | 76.9 | 77.1 | 81.0 | 79.9 | 79.7 | 79.8 |

| NB | 74.3 | 73.0 | 72.2 | 72.5 | 74.8 | 73.5 | 72.9 | 73.2 | 75.2 | 73.8 | 73.1 | 73.4 | 78.9 | 77.3 | 77.0 | 77.1 |

| LSTM | 81.6 | 80.4 | 80.1 | 80.2 | 82.3 | 81.0 | 80.6 | 80.8 | 83.1 | 81.7 | 81.4 | 81.5 | 84.7 | 83.4 | 83.0 | 83.2 |

| RCNN | 82.4 | 81.1 | 80.7 | 80.9 | 83.0 | 81.8 | 81.3 | 81.5 | 83.8 | 82.4 | 82.1 | 82.3 | 85.5 | 84.2 | 83.8 | 84.0 |

| GRU | 83.1 | 81.7 | 81.4 | 81.6 | 83.9 | 82.6 | 82.2 | 82.4 | 84.6 | 83.3 | 82.8 | 83.1 | 86.2 | 84.9 | 84.4 | 84.6 |

| Bi-GRU | 84.2 | 82.9 | 82.4 | 82.7 | 84.8 | 83.6 | 83.0 | 83.3 | 85.4 | 84.1 | 83.7 | 83.9 | 86.9 | 85.7 | 85.1 | 85.3 |

| BERT | 88.4 | 87.1 | 86.7 | 86.9 | 89.1 | 87.9 | 87.3 | 87.6 | 89.9 | 88.6 | 88.1 | 88.3 | 91.3 | 90.0 | 89.7 | 89.8 |

| Model | GoEmotions-1 | GoEmotions-2 | GoEmotions-3 | Amazon Cell Phones | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | |

| BERT | 88.4 | 87.1 | 86.7 | 86.9 | 89.1 | 87.9 | 87.3 | 87.6 | 89.9 | 88.6 | 88.1 | 88.3 | 91.3 | 90.0 | 89.7 | 89.8 |

| ALBERT | 89.2 | 88.0 | 87.6 | 87.8 | 89.9 | 88.7 | 88.3 | 88.5 | 90.7 | 89.4 | 88.9 | 89.1 | 92.0 | 90.8 | 90.3 | 90.5 |

| RoBERTa | 90.4 | 89.3 | 88.9 | 89.1 | 91.1 | 90.0 | 89.6 | 89.8 | 91.9 | 90.7 | 90.3 | 90.5 | 93.1 | 91.9 | 91.6 | 91.7 |

| XLNet | 89.8 | 88.5 | 88.0 | 88.2 | 90.6 | 89.3 | 88.9 | 89.1 | 91.4 | 90.0 | 89.6 | 89.8 | 92.5 | 91.2 | 90.7 | 90.9 |

| RoBERTa + BiLSTM | 91.7 | 90.4 | 90.0 | 90.2 | 92.4 | 91.1 | 90.8 | 90.9 | 93.0 | 91.7 | 91.3 | 91.5 | 94.0 | 92.8 | 92.3 | 92.5 |

| DistilBERT + Attn | 91.1 | 89.9 | 89.6 | 89.8 | 91.8 | 90.5 | 90.1 | 90.3 | 92.5 | 91.2 | 90.8 | 91.0 | 93.5 | 92.3 | 91.9 | 92.1 |

| Our proposed HAM | 94.5 | 93.2 | 93.0 | 93.1 | 95.1 | 93.9 | 93.5 | 93.7 | 95.6 | 94.3 | 93.9 | 94.1 | 96.4 | 95.1 | 94.7 | 94.9 |

| Model Variant | GoEmotions-3 | Amazon Cell Phones | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 | |

| RoBERTa (Base) | 91.9 | 90.7 | 90.3 | 90.5 | 93.1 | 91.9 | 91.6 | 91.7 |

| RoBERTa + BiLSTM | 93.0 | 91.7 | 91.3 | 91.5 | 94.0 | 92.8 | 92.3 | 92.5 |

| RoBERTa + BiLSTM + Attention | 94.3 | 93.0 | 92.7 | 92.8 | 95.2 | 93.9 | 93.5 | 93.6 |

| RoBERTa + BiLSTM + Attention + Focal Loss | 95.0 | 93.8 | 93.4 | 93.6 | 95.8 | 94.5 | 94.1 | 94.3 |

| HAM (Final Proposed) | 95.6 | 94.3 | 93.9 | 94.1 | 96.4 | 95.1 | 94.7 | 94.9 |

| Study | Year | Dataset(s) | Methodology | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | 2021 | GoEmotions | BERT + CPD | 51.96% |

| [70] | 2024 | GoEmotions | BERT | 52.00% |

| [71] | 2021 | SemEval-18 + GoEmotions | Seq2Emo | 59.57% |

| [72] | 2023 | Rest14, Lap14, Twitter | BERT + Gated Graph Attention (GAT) | 82.73% + 79.49% + 74.93% |

| [73] | 2023 | SemEval-2014 Task 4, Twitter, MAMS | Prompt-ConvBERT/Prompt-ConvRoBERTa | 84.27% |

| [74] | 2024 | GoEmotions | CNN + BERT + RoBERTa | 84.58% |

| [75] | 2020 | IMDB, Sentiment140, SemEval-2013/2014, STS-Gold | Naive Bayes (NB) | 75% + 73% + 85% + 76% + 86% |

| [61] | 2025 | GoEmotions | RoBERTa + Adapter + BiLSTM | 87.00% |

| [22] | 2021 | Emo-DB, SAVEE, RAVDESS, IEMOCAP | DT + SVM + RF + MLP + KNN | 92.02% + 88.87% + 93.61% + 77.23% |

| Our Model(HAM) | 2025 | Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews, GoEmotions | BERT/RoBERTa + GAT + BiLSTM + HAM | 94.90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, M.; Khan, L.; Khan, M.Z.; Alhussan, A.A. AGF-HAM: Adaptive Gated Fusion Hierarchical Attention Model for Explainable Sentiment Analysis. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3892. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243892

Kumar M, Khan L, Khan MZ, Alhussan AA. AGF-HAM: Adaptive Gated Fusion Hierarchical Attention Model for Explainable Sentiment Analysis. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3892. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243892

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Mahander, Lal Khan, Mohammad Zubair Khan, and Amel Ali Alhussan. 2025. "AGF-HAM: Adaptive Gated Fusion Hierarchical Attention Model for Explainable Sentiment Analysis" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3892. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243892

APA StyleKumar, M., Khan, L., Khan, M. Z., & Alhussan, A. A. (2025). AGF-HAM: Adaptive Gated Fusion Hierarchical Attention Model for Explainable Sentiment Analysis. Mathematics, 13(24), 3892. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243892