1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the “dual-carbon” strategy and the accelerated electrification of transportation, the number of electric vehicles (EVs) continues to grow, and the construction and operation of public charging infrastructure are shifting from mere scale expansion to a phased upgrade that balances refined scheduling with operational safety [

1]. Compared with traditional transportation energy refueling methods, EV charging loads exhibit characteristics such as short duration, high power, strong randomness, and clustered access, which significantly strengthens their coupling with distribution networks across temporal and spatial dimensions [

2].

Specifically, on the one hand, users must weigh multiple attributes—driving distance, queuing/waiting time, charging costs, and service quality—when selecting charging stations; on the other hand, the concentrated access of vehicles within localized areas and short time windows may induce node voltage deviations, line overloads, and increased network losses, and in severe cases even trigger cascading over-limit events in voltage/current, forming a strongly coupled feedback mechanism between “user-side behavior and grid-side constraints” [

3,

4]. These characteristics indicate that the charging-station selection problem has transcended the realm of individual rational choice and has essentially evolved into a system-level optimization problem that simultaneously accounts for distribution network operational security, energy economics, and infrastructure utilization efficiency.

Existing studies mostly focus on the user-side “cost–time” bi-objective trade-off, often leveraging methods such as multi-objective optimization, Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), or weighted comprehensive evaluation to enhance the interpretability and rationality of recommendations [

5]. However, frameworks based on static weights or experience-based scoring struggle to capture the time-varying characteristics of loads and network states; especially during high-load periods or near vulnerable nodes, they can easily cause recommended results to deviate from the global optimum [

6]. Furthermore, optimizing only the user-side objective function often overlooks the real-time impact of charging loads on power flows and voltage profiles, potentially inducing issues such as voltage sags and capacity bottlenecks [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Although some work seeks to circumvent these problems through capacity caps or coarse-grained voltage constraints, the characterization of key grid-side physical quantities—such as node voltage deviations, branch power limit violations, and I

2R network losses—remains insufficient, making it difficult to achieve a Pareto trade-off between “user experience and grid security” that is verifiable and reproducible with empirical support [

11,

12,

13].

To address the above limitations, this paper develops a multi-objective optimization model for charging station selection that explicitly incorporates distribution-network voltage stability and network energy consumption. Building on the traditional user-side “cost–waiting time” objectives, we introduce voltage deviation—quantified by the L2 norm of nodal voltage deviations—as an independent objective, and use total system losses to characterize grid-side economic performance. By leveraging MATPOWER-based power flow calculations, we quantitatively assess the impact of different vehicle–station assignment schemes on distribution network operating states, forming a dual-domain objective system that couples the user side and the grid side [

14,

15].

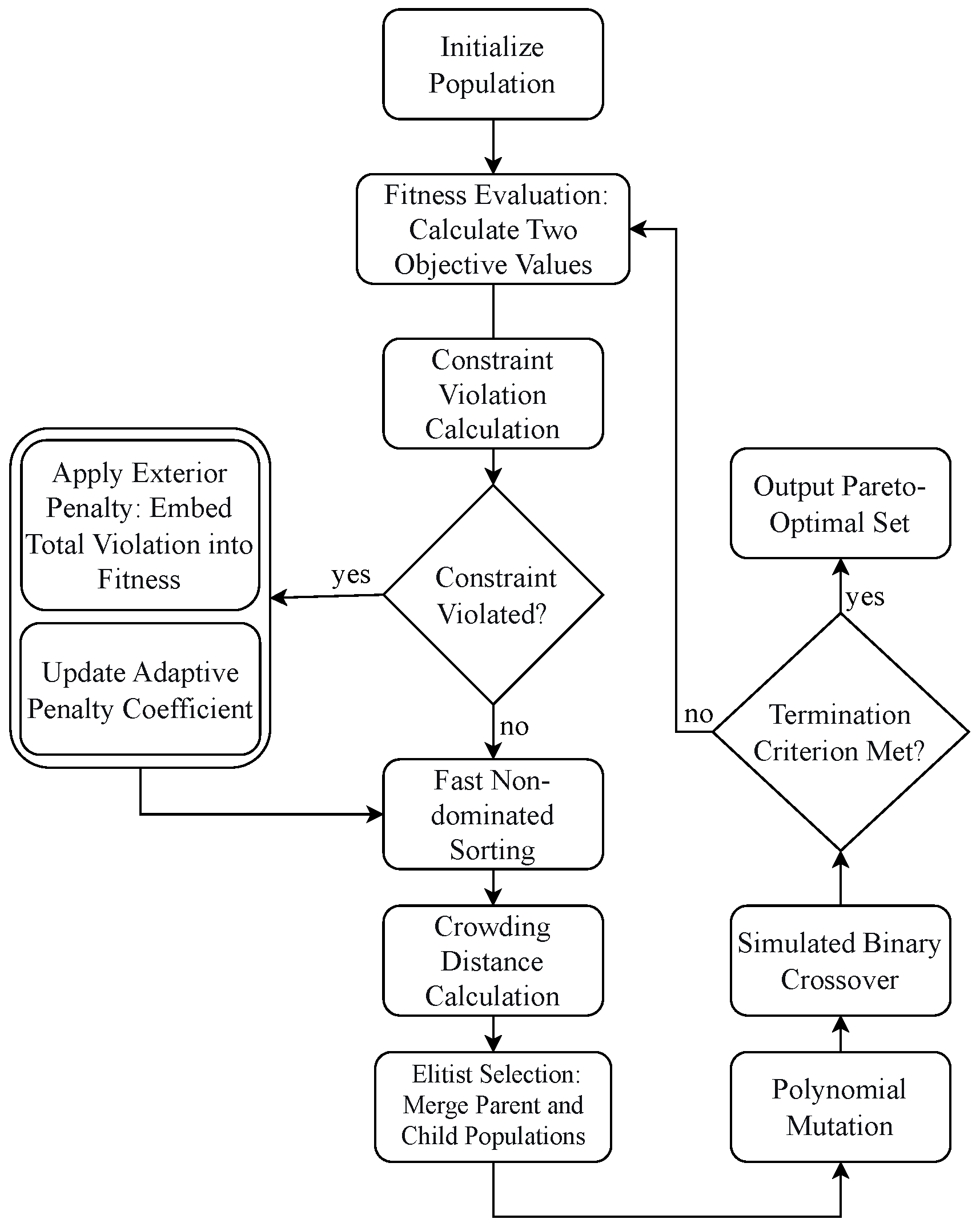

Given the problem’s high dimensionality, stringent constraints, and mixed variables (integrals and continuous), we adopt an improved NSGA-II. Within the framework of fast non-dominated sorting and crowding-distance maintenance, we design an adaptive external penalty function, hybrid encoding with feasibility repair, dynamic crossover/mutation probabilities, and a feasibility-first environmental selection strategy to enhance the algorithm’s sensitivity to electrical–physical constraints and improve convergence efficiency and solution diversity within the feasible region [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Case studies on the IEEE 33-bus distribution system show that if only user-side objectives are optimized, the maximum voltage drop at terminal nodes can reach about 8%, posing an over-limit risk. After incorporating grid-side objectives, with only a slight increase in users’ composite cost (about 3%), the maximum voltage deviation is constrained within 2%, and network losses are significantly reduced (about 12%), achieving co-optimization of user experience and grid security [

20,

21]. Further Pareto-front and spatial load hotspot analyses indicate that the proposed model can proactively avoid “hotspot stations” and bottleneck branches, promote orderly load redistribution across the network, and provide quantitative support for operator-side load–voltage coordinated scheduling, distribution network reinforcement, and siting–sizing of charging infrastructure [

22].

This work makes three contributions: 1. We propose an improved NSGA-II tailored to EV charging–distribution co-optimization, featuring adaptive constraint handling and hybrid encoding that jointly reduce infeasibility and premature convergence. 2. We provide a justified and fair comparison to conventional NSGA-II variants widely used in the literature, demonstrating consistent improvements in feasibility rate, convergence efficiency, and Pareto front quality on user cost and grid stability metrics. 3. We align decision variables and constraints with operational data and standards, clarifying a practical path to deployment.

2. Formulation of a Multi-Objective Location Allocation Model

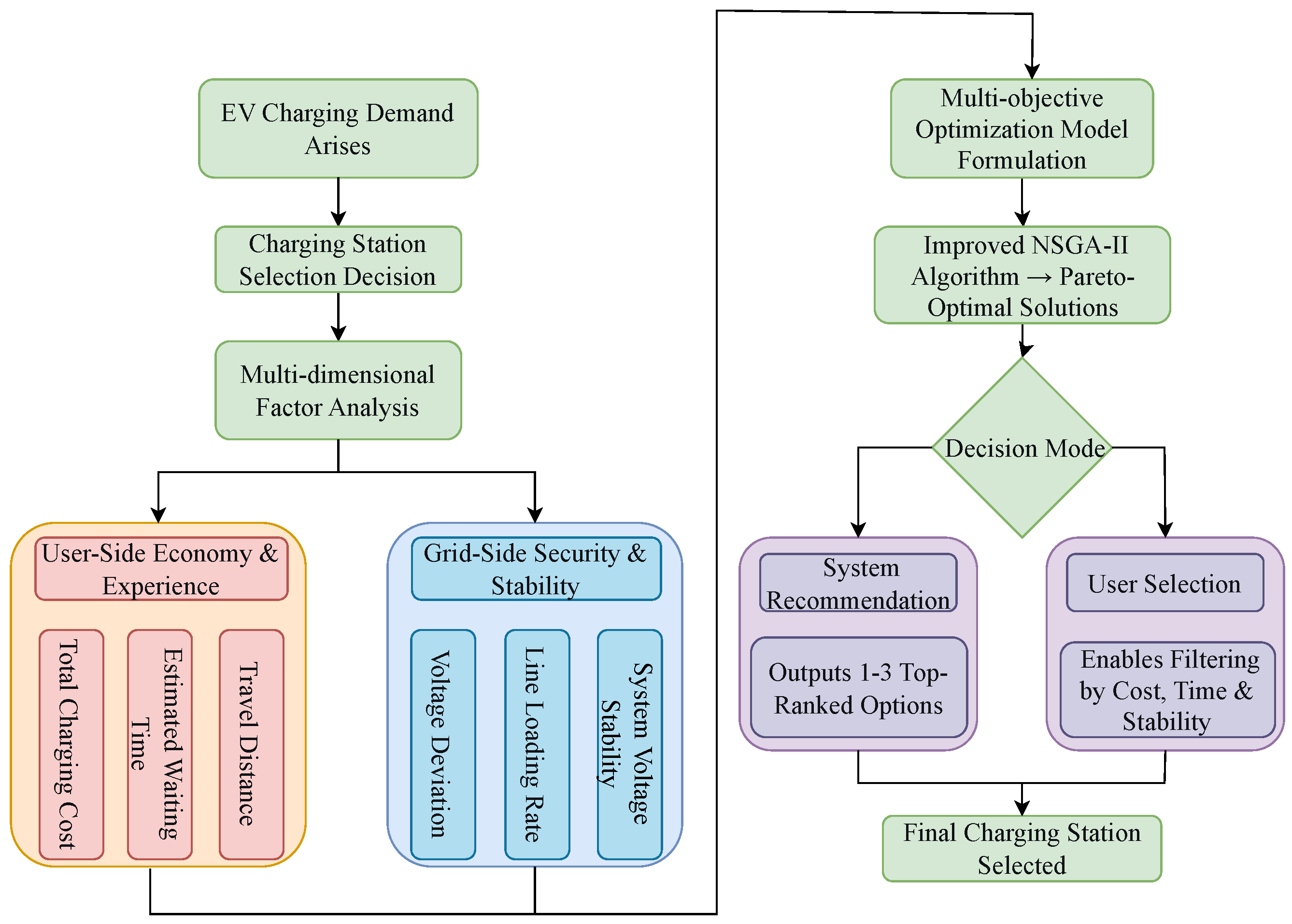

To systematically reconcile the multi-objective tension between user experience and grid security in electric vehicle (EV) charging station selection, we develop a dual-domain, coupled optimization framework. As summarized in

Figure 1, the workflow begins with the emergence of EV charging demand and jointly evaluates user-side economic and experiential factors (e.g., charging cost, queueing time, and travel distance) alongside grid-side operational security indicators (e.g., voltage deviation, line loading, and system-wide voltage stability). These factors are integrated within a multi-objective optimization model that produces a set of Pareto-optimal solutions. The resulting Pareto front can then inform the final station assignment either via system-generated intelligent recommendations or user-driven choices, thereby accommodating heterogeneous preferences and aligning the interests of multiple stakeholders.

The proposed model aims to simultaneously optimize user-side economy and efficiency, as well as grid-side security and economy, through mathematical programming, thereby identifying a set of non-dominated Pareto-optimal solutions. At the core of the model lies the establishment of two comprehensive objective functions:

Objective Function 1 (): User Experience Cost. This function focuses on the user side by integrating the total waiting time and total charging cost into a weighted composite metric, which reflects the overall user experience. Its purpose is to guide electric vehicles towards charging stations that minimize the combined temporal and monetary expenditure.

Objective Function 2 (): Grid Operation Cost. This function concentrates on the grid side, formulating a composite measure of distribution network security and economy through the weighted aggregation of system voltage deviation and total network loss. Its objective is to guide the spatial distribution of charging loads, thereby ensuring the secure, stable, and economical operation of the power grid.

The following sections will elaborate on the composition and modeling process of these two objective functions in detail.

2.1. Formulation of Objective Function 1

In practice, EV users’ sensitivity to travel distance is closely linked to range anxiety. For example, when the state of charge (SoC) of residents in older residential communities or ride-hailing drivers falls below 20%, even small detours can trigger concerns about vehicle immobilization. In addition, each extra kilometer traveled without a fare not only consumes energy but also reduces earning opportunities. Consequently, distance is not merely a spatial metric; it also serves as a direct proxy for a user’s psychological safety threshold [

23].

The temporal dimension of charging—especially queueing time—directly affects vehicle operational efficiency. Delays shorter than 15 min are generally tolerable, whereas waits exceeding 30 min materially erode the earnings of ride-hailing drivers and often indicate localized grid stress during peak hours [

24]. Charging tariffs also have a nontrivial impact on long-term user expenditures. For example, a 0.3 RMB/kWh increase translates into roughly 20 RMB in additional daily cost for a 60 kWh battery, equivalent to about 5–8% of a driver’s net daily income. Moreover, time-of-use pricing not only structures user costs but also functions as a grid-management signal, nudging demand toward off-peak periods and thereby mitigating system congestion [

25].

In summary, distance determines whether a station is reachable, time governs how quickly the vehicle can return to service, and cost shapes the user’s willingness to pay. These dimensions are interdependent and inherently involve trade-offs: the shortest route may entail the longest queue, whereas the lowest-tariff station may be the most distant. Only by integrating these three objectives into a unified Pareto optimization framework can one achieve a synergistic outcome that simultaneously balances user satisfaction, grid security, and resource efficiency.

Objective Function 1 jointly models three core decision variables in EV charging station selection: queueing time, travel distance, and charging duration. We construct a weighted linear aggregation that quantifies their combined effect on user utility as a normalized composite cost. A weighted-sum strategy dynamically assigns relative importance to each sub-objective, enabling globally optimal decisions under multi-objective trade-offs.

The total waiting time

is defined as the sum of the travel time to the charging station and the queuing time at the station, as shown in Equation (

1):

where

represents the distance between electric vehicle

i and candidate charging station

j.

where

v denotes the average travel speed of electric vehicle

i to candidate charging station

j, set at 40 km/h;

represents the queuing time at station

j for vehicle

i.

The minimum charging cost refers to the lowest possible expenditure incurred during the entire charging process, which is primarily composed of the electricity consumption cost and the parking fee, as given in Equation (

3):

where

denotes the charging rate (RMB/kWh) at candidate station

j;

represents the remaining battery level of electric vehicle

i;

is the rated battery capacity, uniformly set as 60 kWh for all vehicles

indicates the parking fee rate (RMB/hour) at station

j;

refers to the required charging duration for vehicle

i at station

j.

where

represents the charging power at station

j, uniformly set as 15 kW for all stations.

To standardize dimensions and reflect user preferences regarding time and cost, weighting coefficients

and

(satisfying

) are introduced to construct a normalized weighted composite objective function:

where

and

represent the minimum and maximum total waiting times in the current solution set, respectively;

and

denote the minimum and maximum total costs in the current solution set, respectively;

and

are the weighting coefficients for time and cost, respectively, which can be configured based on user preferences or scenario requirements. For instance, a time-sensitive user (e.g., a ride-hailing driver) may set

>

, whereas a cost-sensitive user could assign

>

.

2.2. Formulation of Objective Function 2

The spatiotemporal distribution of electric vehicle charging load exhibits dynamic characteristics significantly different from those of conventional residential loads. Its “short-duration, high-power, clustered” integration pattern poses serious challenges to the security, stability, and economic operation of the distribution network. A single DC fast-charging pile typically has a power rating ranging from 60 to 250 kW, equivalent to the combined load of dozens of households. If hundreds of electric vehicles are connected simultaneously to the same distribution node during peak hours, the instantaneous power draw may exceed 30% of the node’s rated capacity, readily leading to transformer overload and feeder current violations. Such spatiotemporal aggregation effects of impactive loads exceed the descriptive capability of traditional load forecasting models and must be accurately assessed through real-time power flow calculations to evaluate their dynamic influence on system state.

The non-uniform spatial distribution of load further exacerbates operational risks. Influenced by users’ “nearest-charging” behavior, certain stations tend to form load “hotspots,” while adjacent nodes remain underutilized. This initiates a “bottleneck–congestion” positive feedback mechanism: localized voltage sags deter users from the affected area, inadvertently causing load to concentrate further at fewer nodes and sharply increasing line losses. Simulation results based on the IEEE 33-node system show that if 500 EVs are connected to the same terminal node, total system losses can rise from 2.1% to 8.7%. Such an increase not only elevates operational costs but may also trigger low-voltage protection, leading to collective power reduction or disconnection of charging piles, thereby compromising power supply reliability.

To systematically evaluate the integrated impact of electric vehicle charging behavior on the distribution network, this paper constructs a weighted objective function that incorporates both voltage stability and system power loss. This function quantifies the comprehensive operational cost from the grid perspective, thereby providing a basis for the spatiotemporal optimization of load scheduling.

Voltage stability is critical for the secure operation of the distribution network. This paper adopts the L2-norm of the voltage magnitude deviations across all nodes from their nominal values as the voltage stability index

, as expressed in Equation (

6):

where

represents the voltage magnitude at the

i-th node, obtained from MATPOWER power flow calculations;

denotes the nominal node voltage, typically 1.0 p.u.

is the total number of nodes in the system. A smaller value of this index indicates a more stable overall system voltage level and higher power quality.

The spatial distribution of charging load directly affects the active power loss (network loss) of the system. The total system power loss

can be expressed as the sum of losses across all branches, as given by Equation (

7):

where

and

represent the active and reactive power flows at the sending end of branch

k, respectively;

denotes the voltage magnitude at the sending end of branch

k;

is the resistance of branch

k;

is the total number of branches in the system. Smaller power loss values indicate higher power transmission efficiency and more economical grid operation.

To standardize dimensions and balance the requirements between voltage stability and economic operation, weighting coefficients

and

(satisfying

) are introduced to formulate a normalized comprehensive grid security objective function:

where

and

denote the minimum and maximum voltage deviation values in the current solution set, respectively;

and

represent the minimum and maximum system power loss values in the current solution set, respectively;

and

are the weighting coefficients for voltage stability and power loss, respectively.

In scenarios with high operational stress (e.g., peak load periods), ; under normal conditions, may be used to emphasize economic operation.

In summary, Objective Function 2 aims to minimize the weighted comprehensive operational cost on the grid side, thereby guiding the spatial allocation of charging load toward configurations that enhance both the security and economic efficiency of the distribution network.

2.3. Assumptions

To effectively accommodate the charging demands of electric vehicles while minimizing the impact of external factors on their charging station selection, the following assumptions are made in this study regarding the charging station siting problem.

Each charging pile can only serve one electric vehicle at a time; simultaneous charging of multiple vehicles by a single pile is not considered.

It is assumed that energy consumption depends solely on travel distance, whereas external factors such as temperature are not considered.

All charging piles are fast-charging-type, with identical specifications and service capacity.

It is important to acknowledge that these assumptions, while necessary to establish a tractable and focused foundational model, introduce certain limitations to the current study. The simplification of one vehicle per pile does not capture the queue dynamics and resource sharing at busy stations. Neglecting the impact of ambient temperature on battery charging characteristics and vehicle energy consumption may lead to inaccuracies in estimating the actual charging duration and travel energy cost. Furthermore, the model does not account for the complex transient dynamics of State of Charge (SOC) during driving and charging.

These limitations, however, clearly delineate valuable pathways for future research. Subsequent work will focus on incorporating more realistic features, such as a multi-vehicle queuing model for charging piles to better represent station congestion; the integration of temperature-dependent charging efficiency and range models; and the development of a dynamic SOC simulation that couples driving patterns with the charging process. These enhancements will further bridge the gap between theoretical optimization and practical deployment in real-world EV charging networks.

2.4. Constraints

The maximum travel distance attainable by the remaining battery charge must exceed the distance between the demand point and the candidate station, expressed as

where

represents the maximum travel distance attainable by the remaining battery charge of vehicle

i;

denotes the distance between electric vehicle

i and candidate charging station

j.

Vehicles that need to consider charging requirements

where

denotes the remaining State of Charge of electric vehicle

i. Vehicles with

are excluded from charging consideration.

Node Transformer Capacity Constraint:

where

represents the apparent power injection at node

j obtained from the power flow solution;

denotes the rated capacity of the transformer at node

j, set to 630 kVA in this study; and

and

are the active and reactive charging load injections at node

j respectively.

Voltage Security Boundary:

where

denotes the voltage magnitude at node

i obtained from the power flow calculation;

represents the nominal voltage; Δ

is the permissible voltage deviation threshold, set as 0.073 per unit.

Thermal Stability Limit:

where

represents the current flow in branch

;

denotes the long-term permissible current-carrying capacity of the conductor, set to 380 A for main lines and 275 A for branch lines in this study.

Among the aforementioned constraints, some are hard constraints that must be strictly satisfied during the optimization process; others are soft constraints, which tolerate minor violations but incur corresponding penalties. The specific penalty mechanism will be elaborated in

Section 4, “Improved NSGA-II”.

4. Case Study

To systematically validate the effectiveness of the proposed improved NSGA-II algorithm in solving the joint electric vehicle charging station selection problem, this section constructs a simulation testbed based on a modified IEEE 33-node distribution system and designs comprehensive comparative experiments.

4.1. Simulation Environment and Parameter Settings

The core of the simulation platform lies in the precise spatial mapping of grid topology and charging infrastructure. Thirty-three public charging stations are individually allocated to corresponding buses in the IEEE 33-node system, ensuring that charging loads accurately impact the distribution network. Online power flow calculations are performed via MATPOWER to obtain precise grid status indicators.

As shown in

Table 1, 300 electric vehicles requiring charging are randomly generated in the simulation. To emulate real-world conditions, the initial SoC of the vehicles follows a uniform distribution between 10% and 90%, with a targeted increase in the probability of low-SoC vehicles (SoC < 50%) to simulate user “range anxiety” behavior. All vehicles are assumed to have a uniform battery capacity of 60 kWh, and their initial locations are randomly distributed within a 50 km × 50 km area.

Table 2 presents the key parameters of the charging facilities. The number of berths at the 33 charging stations is randomly generated following a discrete uniform distribution, with the total system berth capacity guaranteed to be no less than 300, thereby physically eliminating capacity blockage due to berth shortages. To focus on evaluating the core performance of the algorithm and avoid interference from power variations, all charging stations are set to use the same 15 kW charging power without distinguishing between fast and slow charging modes. Charging fees, parking fees, and queuing times are randomly assigned within given ranges to simulate market diversity.

4.2. Analysis of Variable Boundary Control Effectiveness

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, this section compares the optimization results of the standard NSGA-II and the improved NSGA-II. Key comparisons are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Table 3 presents a subset of solutions generated by the standard NSGA-II algorithm. It can be observed that decision variables such as electricity cost and waiting time exhibit significant negative values. This occurs because the standard algorithm lacks effective boundary control and constraint-handling mechanisms, leading to severe boundary violations of decision variables and consequent distortion of the objective functions, rendering the optimization results invalid.

In contrast, the improved NSGA-II algorithm, which incorporates the exterior penalty function and boundary control strategies, produces optimization results as shown in

Table 4. All decision variables, such as electricity cost and waiting time, are strictly confined within physically meaningful ranges (all positive values). This demonstrates that the proposed improvements can effectively handle complex constraints and generate practical charging scheduling solutions.

4.3. Grid Voltage Stability Analysis

Figure 3 illustrates the comparative distribution of voltage magnitudes at each node of the distribution network before and after the integration of electric vehicle charging loads under optimized scheduling using the improved NSGA-II algorithm, validating the effectiveness of the model from a grid security perspective.

Overall Stability Maintenance: Under the extreme scenario of 300 electric vehicles connecting simultaneously, the optimized system voltage profile (red curve) maintains a shape consistent with the typical load-induced voltage distribution of the IEEE-33 system, rather than numerically coinciding with the pre-charging baseline. Although the charging load causes an overall voltage drop (approximately 0.015–0.025 p.u. on average), the overall voltage profile remains undistorted. This indicates that the proposed collaborative optimization strategy successfully achieves spatially balanced load distribution, avoiding local voltage collapse that may result from traditional “nearest-charging” behavior.

Quantification of Key Voltage Indicators: After optimization, the minimum system voltage occurs at Node 18 (0.92 p.u.), representing an 8% deviation from the nominal voltage but only an approximate 2% deterioration compared to the baseline minimum voltage (0.94 p.u.). This result clearly demonstrates that even when the grid is operating near its limits, the algorithm can effectively confine the additional voltage impact induced by EV charging within an acceptable range.

Precise Response to Grid Vulnerabilities: It is noteworthy that the most severe voltage drop does not occur at the electrical terminus (near Node 33) but appears in a mid-section area with higher network impedance (around Node 18). This phenomenon aligns closely with theoretical analysis, demonstrating that the algorithm, through MATPOWER-based online power flow calculations, accurately captures the actual electrical characteristics of the system and accordingly makes rational load distribution decisions. This reflects its capability for precise perception and response to grid operating conditions.

4.4. Multi-Objective Trade-Off and Spatial Load Distribution Analysis

To quantitatively evaluate the comprehensive performance of the proposed coordinated optimization method, a baseline scenario is defined for comparison. This baseline scenario simulates a common user-side selfish strategy that optimizes only the user comprehensive cost objective function while completely ignoring the grid-side security and stability objective function .

As shown in

Table 5, compared with the baseline strategy that considers only user costs, the coordinated optimization method proposed in this study achieves a substantial improvement in grid security performance at the minimal cost of only a 3% increase in comprehensive user cost: successfully limiting the maximum voltage deviation from 8.1% to 2.0%, while simultaneously reducing total system network losses by 12.0%. This result clearly validates the core claims presented in the abstract and demonstrates the exceptional effectiveness of our model in achieving a balance between user and grid interests.

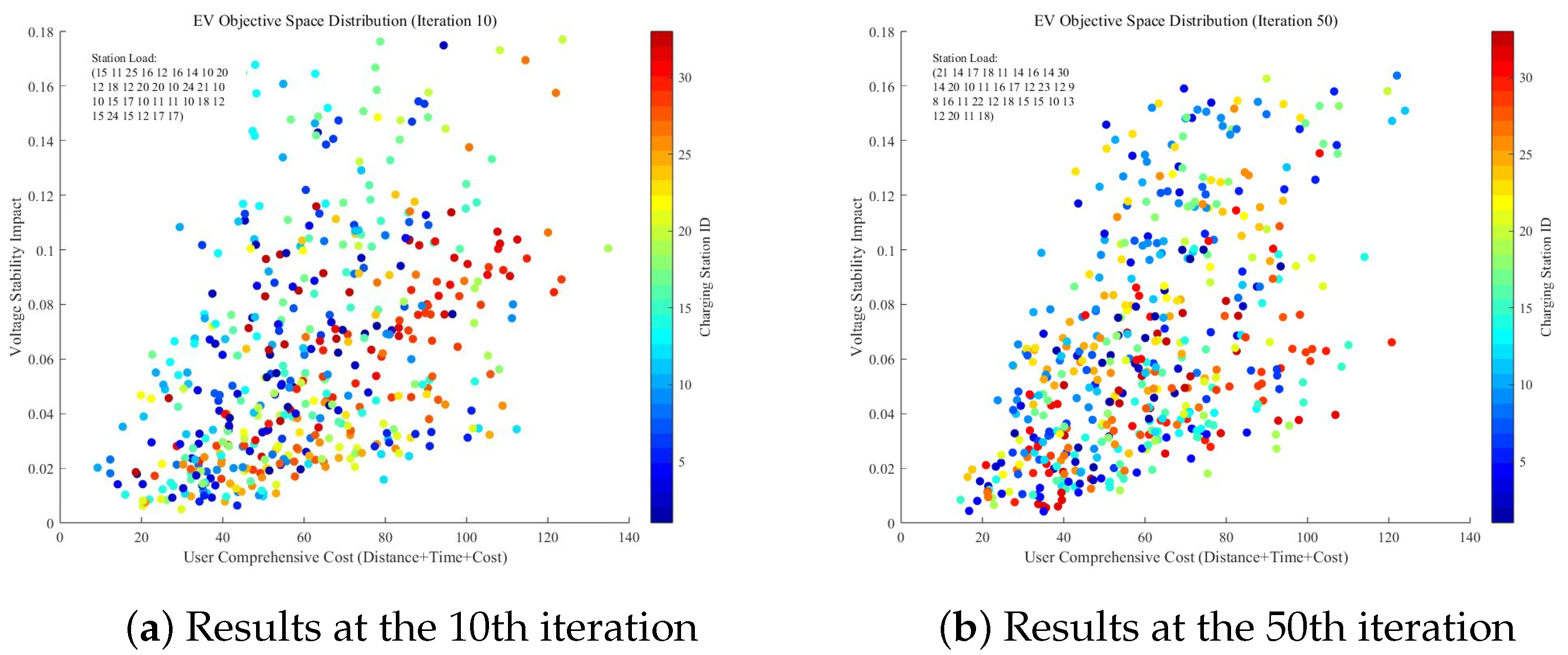

Figure 4 presents the Pareto front obtained after 50 iterations, depicting the allocation of 300 electric vehicles among 33 charging stations. It reveals the inherent trade-off relationship between the comprehensive user cost and grid voltage stability.

Through a comparison of the Pareto fronts and spatial load distributions at the 10th and 50th iterations, it can be observed that the improved NSGA-II algorithm exhibits excellent convergence characteristics. After 50 generations of iterations, the solution set transitions from an initial state of dispersed exploration to converging into a clearly bounded, densely distributed inverted L-shaped Pareto front. This demonstrates that the algorithm has accurately identified the optimal trade-off relationship between comprehensive user cost and grid voltage stability.

Figure 4 displays the Pareto front distribution after 50 iterations, showing the allocation of 300 electric vehicles across 33 public charging stations in the IEEE 33-node distribution system. The horizontal axis represents the normalized comprehensive user cost, where lower values indicate better user-side experience; the vertical axis denotes the voltage stability index

, with smaller values reflecting a more secure distribution network. The scatter points collectively form an “inverted L” shape, densely clustered in the lower-left region and sparse in the upper-right, clearly demonstrating that the NSGA-II algorithm has approached an optimal solution set balancing low cost and high stability within 50 generations.

From the color mapping (1–33 corresponding to node numbers), it is evident that the 300 vehicles are not concentrated in a few stations: distinct hotspots appear at nodes 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, with node 5 carrying the highest load of 125 vehicles, corresponding to , yet still below the severe violation threshold. The loads at all other stations remain below 30 vehicles, and nodes 1, 2, 4, 11, and 32 even exhibit zero load, confirming that the capacity redistribution strategy effectively prevents single-point overloads. The overall L values range between 0.02 and 0.18, with no point exceeding 0.20, indicating that none of the solutions cause significant voltage drops.

In summary, the figure visually validates the effectiveness of the proposed model in balancing comprehensive user cost and distribution network voltage stability, while providing a visual decision-making basis for subsequent charging pile expansion, load scheduling, and grid planning. Electric vehicle charging selection is not an isolated “point decision” but a typical “population–network coupling” problem. If 300 vehicles flock to the same area during similar time periods, the 60–250 kW power of individual charging piles will aggregate into a multi-megawatt load at the node, sufficient to cause a voltage drop of over 5% at the terminus of the 33-node distribution network. Individual vehicle-level decisions cannot capture such nonlinear aggregation effects; only by mapping all vehicles simultaneously onto the 33 nodes can the systemic impact of the total load profile on voltage, power flow, and network losses be accurately reconstructed.

4.5. Trade-Offs from an Individual Vehicle Decision Perspective

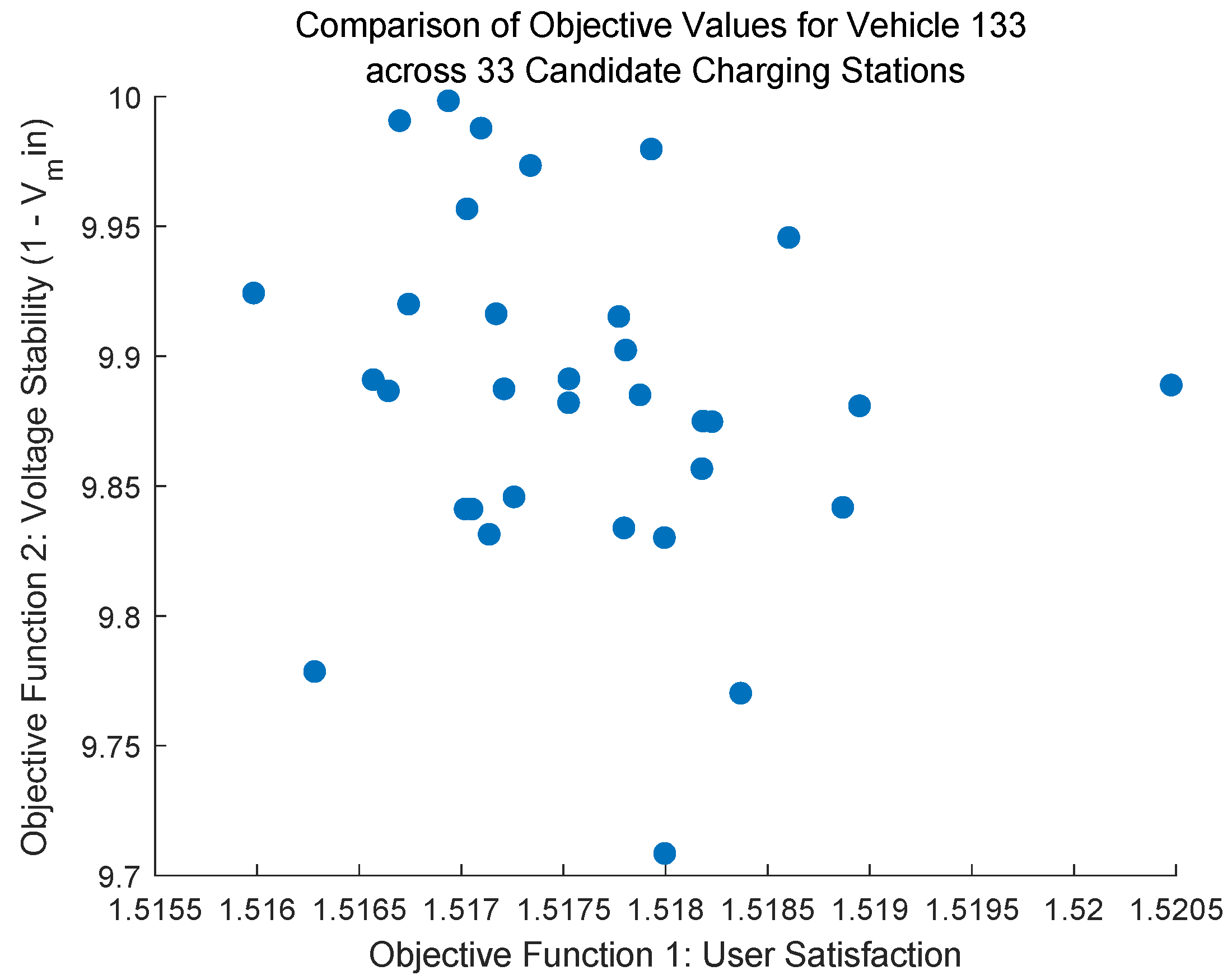

Figure 5 further illustrates the trade-off relationship between the two objectives for a single electric vehicle across 33 candidate charging stations from an individual decision-making perspective.

The curve exhibits a concave shape, visually demonstrating the nonlinear conflict between “low cost” and “high stability” for a single vehicle. By selecting the point that best aligns with its preference on the frontier, the vehicle can identify an optimal charging station that balances user benefits and distribution network security without significantly increasing costs. This provides a direct basis for personalized charging recommendations.

To quantitatively assess the trade-off relationship between the two objectives shown in

Figure 5, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis on the data points of Vehicle 133 across all 33 candidate charging stations. The results show a significant negative correlation between the user comprehensive cost and the voltage stability impact (r = −0.82,

p < 0.001). This strong negative correlation statistically confirms the inherent conflict between the two objectives: a decrease in user cost is generally accompanied by an increase in grid stability impact, and vice versa. This quantitative analysis provides numerical evidence supporting the observed nonlinear trade-off relationship in the figure.