Abstract

This study proposes an enhanced model for optimizing cost-sharing strategies in competitive manufacturing supply chains, integrating the effects of learning, forgetting, and sustainable green practices. Building on the foundational framework of a monopolistic competition environment, the research extends the traditional cost allocation between an incumbent manufacturer and a midstream assembly plant by incorporating environmental costs, such as carbon emissions taxes, into the total cost function. The model accounts for learning and forgetting dynamics in both setup and production stages, influencing setup costs, production costs, and inventory holding costs, alongside defensive costs against competitors. A novel sustainability extension introduces an environmental cost component, reflecting the impact of demand-driven emissions under varying cost-allocation rates. Sensitivity analyses demonstrate that a higher rate of competitor entry, reduced dispersion in defensive costs, and elevated learning/forgetting rates increase the optimal cost-allocation rate and total expected cost, with production-stage effects dominating setup-stage impacts. Furthermore, the inclusion of green practices reveals a trade-off, where higher environmental taxes and emission rates lower the optimal allocation to mitigate emissions, albeit at an increased overall cost. Numerical simulations validate the model, offering insights for managers to balance economic efficiency with environmental sustainability in dynamic supply chain contexts.

Keywords:

cost-sharing strategy; competitive manufacturing; learning and forgetting; sustainable green practices; environmental cost; supply chain optimization; carbon emissions MSC:

62F15; 62N02; 62N05; 62C10; 65C20

1. Introduction

In an era characterized by rapid technological advancement and heightened environmental awareness, manufacturing systems face the dual challenge of maintaining cost efficiency and achieving sustainability. Traditional production cost models—designed for stable and predictable environments—often overlook the dynamic and interdependent nature of modern supply chains. As industries shift toward knowledge-intensive operations and carbon-conscious production, firms must manage not only economic performance but also learning adaptability, knowledge retention, and ecological responsibility.

Learning and forgetting are central to this challenge. Learning enhances productivity through accumulated experience, while forgetting—driven by interruptions, employee turnover, or technological changes—erodes these gains over time. These opposing forces directly influence setup, production, and inventory costs, making them crucial determinants of total system performance. When embedded in vertically integrated supply chains, such dynamics interact with strategic decisions like cost allocation between upstream and midstream production units. An efficient allocation mechanism must therefore reflect how learning and forgetting evolve over time and affect operational efficiency.

At the same time, growing environmental regulations have made sustainability an unavoidable consideration in cost management. Carbon taxation and related policies, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), require manufacturers to internalize environmental externalities into their financial models. This paradigm shift transforms cost-sharing from a simple accounting exercise into a multi-objective optimization problem that balances economic efficiency, competitive positioning, and environmental stewardship.

Building on prior work that links production learning to cost allocation [1,2,3], this study extends the traditional framework by incorporating sustainability-oriented cost components. The proposed model introduces an environmental cost function representing carbon emissions under variable taxation, integrated with dynamic learning-forgetting behavior and competitive market entry. Through this integration, the study aims to derive an optimal cost-sharing rate that minimizes total expected cost while maintaining equilibrium between operational efficiency and sustainability.

Recently, AI and digital manufacturing have introduced data-driven approaches that minimize costs using real-time sensing and machine learning. However, these methods often overlook human factors like learning, forgetting, and cross-stage cost interactions. Our study addresses this gap with an analytical model that incorporates learning–forgetting dynamics and environmental costs. The model reveals how experience and knowledge decay shape long-term cost structures and interact with carbon expenses, thus complementing data-centric AI methods by providing strategic insights for sustainable supply chains.

Ultimately, to clarify the contributions of this work, the study’s objectives are summarized as follows: (1) to develop an integrated cost-sharing model that simultaneously incorporates learning–forgetting dynamics, competitive entry behavior, and environmental cost internalization; (2) to examine how learning and forgetting affect the evolution of setup, production, and inventory costs, and how these cost trajectories interact with carbon-related expenses; (3) to determine the optimal cost-allocation rate under stochastic competitor entry and sustainability constraints; (4) to provide theoretical insights into the structural interactions among operational learning, cost sharing, and environmental taxation in competitive supply chains; and (5) to offer practical managerial guidance for manufacturers seeking to balance economic efficiency, experience retention, and environmental responsibility.

2. Literature Review

The optimization of cost-sharing in modern manufacturing integrates three major theoretical streams: (1) the dynamics of learning and forgetting in production systems, (2) cost-sharing strategies as mechanisms for cooperative efficiency, and (3) carbon tax and green production models that internalize environmental costs. These domains, though historically independent, converge on a shared premise: that manufacturing efficiency arises not only from minimizing direct costs but also from dynamically managing knowledge retention, coordination incentives, and ecological externalities. The following sections review key studies across these research areas and establish the theoretical foundation for the integrated model proposed in this work.

2.1. Learning and Forgetting in Production Systems

The study of learning and forgetting has evolved from early productivity models into a complex understanding of behavioral and process adaptation. Ho and Huang [1] introduced the joint consideration of learning and forgetting in cost allocation within monopolistic competition, showing that both factors significantly influence total system cost. Subsequent research by Jaber and Givi [2] emphasized imperfect production processes, integrating quality defects and human learning rates to demonstrate how operational knowledge decays over time.

Later developments extended these ideas into more realistic and collaborative manufacturing contexts. Asghari et al. [4] investigated human-centric learning-forgetting interactions across networked production systems, emphasizing the role of collaboration in mitigating forgetting effects. Similarly, Giri and Glock [5] modeled worker experience within closed-loop supply chains, revealing that stochastic product returns amplify the sensitivity of profits to worker learning levels. Liu, Wang, and Leung [6] contributed computational methods by applying hybrid bacteria foraging algorithms to optimize worker assignment under learning-forgetting constraints, confirming the nonlinear nature of these effects.

Forgetting has also been linked to production stability and scheduling. Ostermeier and Deuse [7] examined how intermittent production leads to skill degradation, suggesting that stable scheduling mitigates cost escalation. Xu, Xie, and Hall [8] integrated task similarity into sequencing problems, showing that forgetting significantly alters optimal task order and throughput efficiency. Complementarily, Tercan, Deibert, and Meisen [9] connected continual learning in neural networks with manufacturing quality prediction, proposing algorithmic analogs to human learning decay.

Empirical studies highlight workforce-specific dimensions: Boenzi et al. [10] demonstrated that aging workers exhibit slower learning but higher stability, while Rerkjirattikal, Wanwarn, and Olapiriyakul [11] revealed that boredom-induced dissatisfaction accelerates forgetting in job rotation settings. Dey and Giri [12] and Giri and Masanta [13] further expanded the framework by embedding learning into inspection and quality-driven production, respectively, emphasizing stochastic influences and the feedback between operational learning and product reliability. Collectively, these studies underscore that learning and forgetting are fundamental drivers of long-term cost behavior, forming the operational core of the present study’s model.

2.2. Cost-Sharing Mechanisms and Cooperative Strategies

Cost-sharing functions as a strategic coordination mechanism to align incentives between supply chain partners, especially under asymmetric capabilities and information. He et al. [14] demonstrated that manufacturers can use cost-sharing contracts to promote green innovation among suppliers, particularly when environmental investment yields spillover benefits. Taleizadeh, Niaki, and Alizadeh-Basban [15] explored closed-loop supply chains combining carbon abatement and quality improvement, concluding that optimal cost-sharing enhances overall profitability and sustainability performance.

Cai, He, and He [16] linked cost-sharing with information transparency under varying warranty policies, suggesting that joint responsibility reduces opportunistic behavior. Dai, Zhang, and Tang [17] compared cartelization versus cost-sharing modes in green supply chains and found that cooperative cost-sharing generally achieves higher environmental and economic efficiency. Wu, Fan, and Cao [18] expanded the scope to include government subsidies, developing a Nash game model where cost-sharing supports both carbon emission reduction and sales effort optimization.

Policy-oriented research has strengthened these findings. Song, Lai, and Li [19] analyzed cost-sharing in cross-regional pollution control, demonstrating that sharing mechanisms prevent regional free-riding and improve cooperative compliance. Similarly, Yan et al. [20] empirically confirmed that government subsidies magnify the positive impact of cost-sharing on green innovation by lowering financial barriers for smaller firms. These studies collectively position cost-sharing as both a coordination and incentive tool that harmonizes efficiency and sustainability objectives.

Integrating learning and forgetting into cost-sharing models further enriches this perspective. While conventional frameworks assume constant efficiency, learning-forgetting dynamics imply that firms’ relative competencies evolve. This makes static cost-sharing suboptimal over time. By incorporating these dynamics—as this study does—cost allocation can adapt to temporal changes in productivity, allowing firms to maintain equitable and efficient cooperation even as operational capacities shift.

2.3. Carbon Tax Policies and Green Production

The increasing implementation of carbon taxes has transformed cost structures across global manufacturing. Zhang et al. [21] analyzed how carbon taxation influences production and pricing decisions in co-opetitive supply chains, finding that higher carbon costs shift equilibrium strategies toward reduced output and greater investment in clean technologies. Fu et al. [22] refined this analysis by considering emission asymmetry, demonstrating that firms with higher emission baselines respond more sensitively to carbon taxes when adjusting production rates and technology portfolios. Liu et al. [23] extended carbon tax research to agricultural supply chains, emphasizing how investment cooperation and cost-sharing in emission reduction can mitigate profit losses.

More recent studies provide additional evidence of the evolving role of carbon taxation. Zhang et al. [24] assessed the welfare impact of China’s carbon tax under the carbon neutrality target, revealing heterogeneous effects across different resident groups. Zhang et al. [25] applied conjoint analysis to carbon tax pricing and found that policy acceptance and effectiveness depend strongly on perceived fairness and behavioral responses. Li et al. [26] examined cross-border supply chain remanufacturing under mixed carbon abatement policies, showing that import quotas substantially alter firms’ remanufacturing incentives and carbon compliance strategies.

Subsequent studies have compared taxation mechanisms with alternative sustainability incentives. Deng et al. [27] and Hua et al. [28] contrasted carbon taxes with cap-and-trade systems, emphasizing the strategic implications of carbon border adjustments on cross-regional production. Eslamipoor and Sepehriyar [29] and Sun et al. [30] integrated carbon tax, cap, and trading mechanisms into a unified framework to promote green supply chains, demonstrating that mixed policy instruments often yield superior environmental and economic outcomes.

Recent empirical studies examine how environmental regulation, policy uncertainty, and carbon-related mechanisms influence firm decisions within green supply chains. Several investigations have focused on the emerging Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Acar, Aşıcı, and Yeldan [31] analyzed its potential macroeconomic impacts on non-EU manufacturing sectors, demonstrating that carbon-intensive exporters must improve technology or efficiency to mitigate cost pressures. Zhong and Pei [32] provided a systematic review of recent CBAM developments, highlighting its implications for supply chain restructuring and carbon accounting practices. Meanwhile, Erdogdu [33] emphasized the opportunities and challenges CBAM poses for non-EU economies, particularly regarding emission transparency and competitiveness. Complementing these policy-oriented studies, recent research also explores risk and uncertainty in operational and environmental decision-making. Qi, Li, and Zhang [34] modeled joint production and emission reduction under risk aversion, showing how carbon price volatility and emission tax rates shape firms’ optimal strategies. Fang, Hsu, and Chu [35] integrated logistics and green investment into a synergistic supply chain framework, finding that coordinated carbon management enhances system-wide efficiency. Similarly, Zhang, Wang, and Liu [36] compared carbon taxes and low-carbon subsidies, identifying policy thresholds at which firms shift from passive tax avoidance to proactive green investment. Together, these studies underscore the multifaceted interactions among carbon regulation, operational risks, and green innovation incentives.

2.4. Summary

The existing literature provides strong theoretical foundations across three key research domains. Studies on learning and forgetting emphasize operational adaptation and cost evolution; research on cost-sharing underscores coordination and incentive alignment; and investigations into carbon taxation reveal the macro-level impact of environmental policies on firm behavior. However, the integration of these domains remains limited. Few models jointly capture the interaction between learning-forgetting dynamics, cooperative cost allocation, and environmental cost internalization. This study bridges these gaps by formulating a unified model that incorporates operational learning, strategic cost-sharing, and environmental taxation within a single optimization framework—advancing both theoretical understanding and practical applicability for sustainable manufacturing systems.

3. Model Development and Analysis

3.1. Problem Description

As a manufacturer operating within a highly competitive and sustainability-oriented supply chain, our firm faces critical challenges in optimizing cost allocation strategies under dynamic market and environmental conditions. Positioned as an incumbent in a monopolistically competitive market, we collaborate vertically with a midstream assembly plant—the upstream unit (our firm) producing unfinished components, and the midstream plant completing finished goods for downstream customers.

In such a vertically integrated production system, determining how to allocate costs between the upstream and midstream stages is a complex strategic decision rather than a purely accounting task. Let denote the cost allocation rate borne by the assembly plant, implying that the incumbent bears the complementary share . This allocation parameter directly influences multiple operational and strategic dimensions—most notably, learning and forgetting effects, competitive defense mechanisms, and environmental sustainability expenditures.

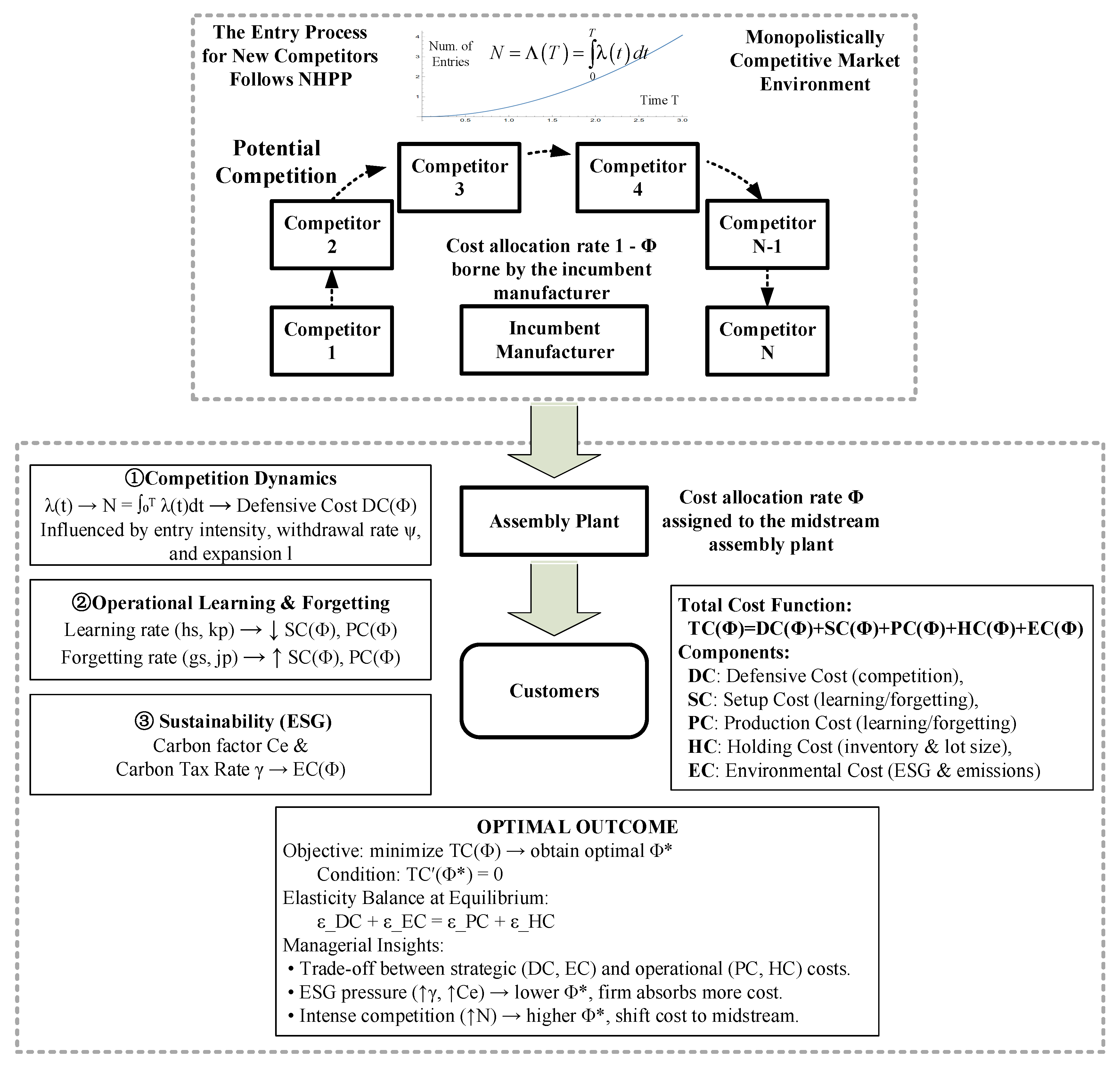

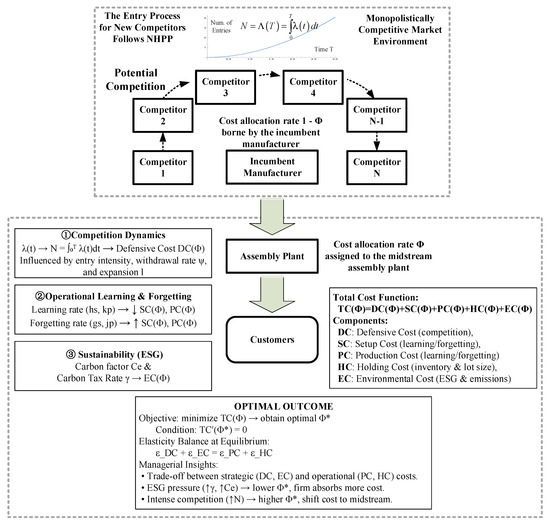

The market environment is further complicated by time-dependent competitor entry, where new firms enter the market following a nonhomogeneous Poisson process (NHPP) with an increasing intensity function . This represents the realistic progression of competitive dynamics: as the product and technology mature, market transparency increases and entry barriers diminish, resulting in an accelerating influx of competitors. The expected number of entrants within a predetermined planning horizon is given by the cumulative intensity function . Consequently, the effective demand faced by the incumbent declines exponentially by a factor , capturing market erosion mitigated through cost-sharing and joint defensive actions between the production stages. The overall framework of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Framework of the Study.

Figure 1 presents an integrated overview of the conceptual and mathematical framework developed in this study. The upper section illustrates the competitive environment, where potential entrants arrive according to a non-homogeneous Poisson process (NHPP) and progressively erode the incumbent’s demand as market saturation increases. This portion of the figure demonstrates how entry intensity, cumulative entrants, and the resulting defensive costs collectively influence the upstream manufacturer’s strategic behavior.

The middle section highlights the interaction between the incumbent manufacturer and the midstream assembly plant. The division of cost responsibilities—represented by the allocation rates and —serves as the central decision variable linking competitive dynamics, operational learning–forgetting processes, and environmental cost structures. This stage visually emphasizes the bilateral nature of cost sharing and how it shapes the flow of products and costs toward downstream customers.

The lower portion of the figure consolidates the five major cost components—defensive cost (DC), setup cost (SC), production cost (PC), holding cost (HC), and environmental cost (EC)—into the total cost function . It also summarizes the optimization problem and the managerial insights derived from the model analysis. Importantly, each block shown in Figure 1 is formally defined and analytically developed in the subsequent subsections of Section 3, guiding the reader from the high-level conceptual framework to the detailed mathematical formulation.

At the operational level, learning and forgetting effects introduce an additional layer of complexity. Learning enhances productivity and reduces setup and production costs over time, as workers and systems accumulate experience. Conversely, forgetting effects—caused by interruptions, production downtime, or workforce turnover—erode these gains. The coexistence of these two opposing effects affects these functions. Therefore, an effective cost allocation policy must balance these internal production dynamics with the external pressures of market competition.

Moreover, the growing global emphasis on environmental sustainability imposes additional strategic considerations. Emerging regulatory mechanisms—such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)—compel manufacturers to internalize carbon-related externalities. Demand-driven production inherently increases carbon emissions, which translate into environmental costs (ECs) within the firm’s total cost structure. Consequently, the firm must integrate these environmental costs into its optimization framework, ensuring compliance with regulatory expectations while maintaining economic viability.

The firm’s total expected cost thus comprises five interdependent components, , where denotes the defensive cost against competitors, and reflect learning and forgetting in setup and production stages, represents inventory holding costs influenced by demand reduction, and captures environmental taxation and emission-related expenses. The goal is to determine the optimal cost allocation rate that minimizes while sustaining competitiveness and meeting environmental compliance. Accordingly, the research problem addressed in this study is twofold: (1) To develop a mathematical model that captures the interaction between cost allocation, learning and forgetting effects, and stochastic competitive entry dynamics; and (2) To extend this model by incorporating environmental sustainability considerations, particularly the impact of carbon emission costs on the firm’s optimal cost allocation strategy. Table 1 summarizes the notations and symbols used in this study.

Table 1.

Notations and Symbols.

From the manufacturer’s perspective, solving this optimization problem offers actionable Managerial Insights. It reveals how variations in competitor entry rates, dispersion of defensive costs, and learning-forgetting rates affect the equilibrium allocation of costs between production stages, and how the inclusion of environmental factors reshapes this balance. Ultimately, the objective is to enhance economic efficiency, supply chain fairness, and environmental responsibility, thereby securing long-term competitiveness in an increasingly carbon-conscious marketplace.

3.2. Model Framework and Assumptions

To analytically capture the manufacturer’s decision environment, we formalize the total-cost minimization problem within a finite planning horizon . The incumbent firm (upstream) and the midstream assembly plant jointly operate within a monopolistically competitive structure in which the incumbent produces unfinished components, and the assembly plant completes finished goods for downstream customers. The total cost incurred by the incumbent depends on the cost-allocation rate , the dynamics of competitor entry, and the learning-forgetting behavior embedded in the production processes.

3.2.1. Competitor Entry Process

Competitors are assumed to enter the market following a nonhomogeneous Poisson process (NHPP) with an intensity function that is non-negative and non-decreasing over time. To ensure integrability and realistically represent market entry saturation, the intensity function may be specified, for example, as follows:

where represents the maximum (long-run) entry intensity, and governs the speed at which the market approaches saturation. When is large, competitor entry rises quickly before leveling off; when is small, saturation occurs more gradually. Integrating over the planning horizon yields the expected cumulative number of entrants:

This formulation ensures that the expected number of competitors increases over time but converges to a finite upper bound as entry growth stabilizes—an effect consistent with limited market capacity, technology diffusion constraints, and regulatory barriers. The growth in competition reduces the incumbent manufacturer’s attainable market share. Following standard diffusion-based representations of competitive erosion, the effective demand for the incumbent is modeled as an exponential decay function of the number of entrants:

where represents the baseline demand rate for unfinished products in the absence of competitors. A higher cost allocation rate (greater cost borne by the assembly plant) mitigates the incumbent’s exposure to market erosion, preserving a larger share of effective demand.

3.2.2. Cost Components

The incumbent’s total expected cost over the planning horizon comprises five interrelated components:

where each term reflects a distinct operational or strategic cost category.

- (1)

- Defensive Cost (DC)

The defensive cost represents expenditures required to sustain market position and counter competitive pressure. Accounting for the withdrawal fraction of competitors and the exponential scaling of defense with , we define:

where is an expansion constant, is the mean defensive cost per competitor, and is the expected number of entrants. A higher allocation rate, , places greater financial responsibility on the midstream stage and reduces the extent of shared commitment within the supply chain. This separation increases the marginal cost of coordinating defensive actions—such as joint marketing, differentiation, and customer retention—because greater managerial alignment and negotiation are required as cost responsibilities diverge. These coordination frictions tend to compound rather than increase linearly, causing each increment in to disproportionately elevate defensive expenditures. Accordingly, the defensive cost is modeled to grow exponentially with , capturing the cumulative and escalating nature of these coordination challenges.

- (2)

- Setup Cost (SC)

Setup cost arises at the beginning of each production run and reflects the interplay of learning and forgetting in repetitive operations. Let be the total production volume within . Then:

where is the first-unit setup cost, is the forgetting rate, and is the learning rate.

The functional form captures learning–forgetting dynamics:

Learning effect () reduces the setup requirement as production repeats, causing to decline with iii. A higher learning rate implies stronger retention of operational knowledge, accelerating the reduction in marginal setup cost.

Forgetting effect () counteracts learning by increasing the baseline setup requirement whenever experience decays—for example, due to production interruptions, machine resets, or worker turnover.

Thus, the setup cost embodies the balance between cumulative experience (learning) and efficiency loss (forgetting), providing a more realistic representation of operational performance in repetitive production environments.

- (3)

- Production Cost (PC)

Production cost reflects the cost of manufacturing units, adjusted for learning and forgetting effects and scaled by the allocation ratio. It is defined as:

where is the production fixed cost, denotes the first-unit production cost, measures the lot-size sensitivity of production cost, represents the forgetting rate in production, and the learning rate. Here, the incumbent bears a fraction of production-related expenses, consistent with the cost allocation structure depicted in Figure 1.

- (4)

- Inventory Holding Cost (HC)

Inventory costs arise when production output exceeds realized demand. Assuming a production rate and effective demand , the average inventory level is approximated by , yielding:

where is the inventory holding cost per unit and denotes the sensitivity of inventory cost to lot size. As declines with increasing market entry , inventory accumulation intensifies, especially under aggressive production scheduling.

- (5)

- Environmental Cost (EC)

Incorporating sustainability into cost modeling, the environmental cost captures carbon-related expenses under regulatory mechanisms such as carbon border adjustment taxes. The environmental cost is formulated as:

where is the carbon tax rate, and is the emission coefficient representing emissions per production unit. This term integrates environmental externalities directly into operational decision-making, consistent with ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance Perspective) and carbon-pricing frameworks such as the EU CBAM.

- (6)

- Objective Function

A higher transfers more cost to the assembly plant but increases defensive expenditures; a lower enhances learning efficiency but raises production, inventory, and environmental costs.

3.3. Theoretical Analysis of the Model

This section presents analytical results concerning the structural and curvature properties of each cost component—setup cost (SC), production cost (PC), defensive cost (DC), holding cost (HC), and environmental cost (EC)—and their implications for the total cost function TC(Φ). We establish sufficient conditions for convexity and discuss their managerial interpretations in the context of cost allocation and sustainability strategy.

3.3.1. Defensive Cost Dynamics

Lemma 1.

Monotonicity and Convexity of Defensive Cost. With , ,

and . Then: (1) is strictly increasing in ; (2) is strictly convex.

Proof of Lemma 1.

Let the defensive cost function be . To verify, compute the first derivative and the second derivative . □

- Managerial Insight: At higher values of (indicating greater costs borne by the midstream), defensive and coordination expenditures increase rapidly; over-allocating costs to the upstream segment can quickly become counterproductive. Furthermore, the convexity implies that marginal defensive spending increases rapidly at higher , emphasizing the need to limit over-allocation to the midstream partner; otherwise, defensive expenses will dominate total cost.

3.3.2. Learning and Forgetting in Setup and Production

Let .

Define (discrete) cumulative sums and for integer . In the analysis below, we use the standard continuous approximation (Leibniz rule) when differentiating through an upper limit .

Lemma 2.

Setup cost is increasing and concave in output. Let . If and (so ), then is positive and non-increasing in . Consequently, is increasing and discrete-concave in :

Hence, is increasing in and concave in .

Proof of Lemma 2.

For is non-increasing in ; thus is non-increasing. The difference sequence of a non-increasing positive sequence is non-increasing, which implies discrete concavity of its partial sums. Multiplying by preserves these properties. □

Remark 1.

Under the integral approximation,

and since , the integrand decreases, giving concavity in

as well.

- Managerial Insight: Setup cost increases with output but at a diminishing rate due to learning. Because the setup cost function is concave in output, the marginal setup cost becomes smaller as production progresses. Importantly, the parameter , which represents the rate at which learning is retained, has a direct influence on this cost curvature. A higher learning rate accelerates the reduction in the per-setup cost , thereby lowering the total setup cost . This indicates that improving learning efficiency—through worker training, standardization, or automation—provides tangible economic benefits. Firms with higher learning rates experience faster reductions in marginal setup cost, enabling larger production batches with lower incremental cost burdens. In contrast, weaker learning retention leads to slower efficiency gains and higher cumulative setup costs. Therefore, enhancing the learning rate is beneficial for lowering operational cost and stabilizing setup-related expenses over repeated production cycles.

Lemma 3.

Production cost has mixed dependence on

. Let

Then, under the continuous approximation,

Because increases in its argument while decreases, the derivative comprises a negative term that becomes more negative as increases (via ), and a positive term whose magnitude depends on . Therefore, may decrease for small (learning dominates) and increase for large (allocation and growth in dominate), i.e., it can be unimodal.

Proof of Lemma 3.

Differentiate by the product/chain rule, replacing by under the Leibniz approximation. Monotonicities of and give the sign structure. If eventually dominates the first (negative) term, a unique turning point occurs (details can be formalized with standard monotone-ratio arguments because is positive, decreasing, and increases in ). □

- Managerial Insight: Early on, learning reduces production cost; past a point, pushing more burden to the midstream () and higher volumes reverse the effect—there exists a “right-sized” allocation window for production efficiency.

Proposition 1.

Flattened learning makes

and

near-linear.

Proof of Proposition 1.

If (so ) and , then ; hence, . Therefore, and , both nearly linear in ; in particular, becomes small relative to convex components, immediately from limits and . □

- Managerial Insight: Learning and forgetting jointly determine the slope of operational costs. When the production system is mature and processes are standardized (resulting in a flattened learning curve), setup and production costs become predictable and stable, allowing the firm to focus on strategic factors such as competition and sustainability. This condition also promotes the convexity of total costs, thereby simplifying optimization. In brief, in mature, standardized operations, the learning curve disappears; strategic factors—such as defense and ESG considerations—dominate the shape of the total cost ().

3.3.3. Inventory Holding and Demand Interaction

Lemma 4.

Quadratic Convexity of Holding Cost

.

Proof of Lemma 4.

Given and , we have .

Since and , is positive if , i.e., production capacity effective demand. □

- Managerial Insight: When production capacity exceeds expected sales, holding costs rise faster as the firm retains unsold inventory. Convexity of implies that overproduction is increasingly costly, encouraging tighter synchronization between upstream and midstream production schedules—especially under competitive pressure that erodes demand.

3.3.4. Environmental Cost Integration

Lemma 5.

Monotonicity and Convexity of Environmental Cost

.

Proof of Lemma 5.

With we obtain

Hence, is strictly increasing and convex in . □

- Managerial Insight: Increasing the cost allocation rate () amplifies production activity at the midstream stage, thereby increasing carbon emissions and sustainability costs. The convex nature of signals nonlinear growth in environmental burden, underscoring the strategic value of carbon-efficient operations and emission control investment to limit upward cost curvature.

3.3.5. Properties of Total Cost

Proposition 2.

A Sufficient Condition for Convexity of Cost Function.

Proof of Proposition 2.

Assume: (1) and ; (2) and (flattened learning/forgetting) so that with small ; (3) Either on the relevant domain (so ), or is bounded below by with modest . □

Then, for all if

In particular, when inventory curvature is non-negative (e.g., ), is convex provided and are not too small. Sum the component second derivatives. Under the stated bounds, dominates any negative curvature from and the small , yielding .

Corollary 1.

Existence and Uniqueness of the Optimal Solution of Total Cost.

Proof of Corollary 1.

Under Proposition 2, is continuous and convex on ; hence, the program has a unique global minimizer . The Weierstrass theorem guarantees existence on a compact set, while strict convexity ensures uniqueness. □

- Managerial Insight: When strategic/ESG curvatures (via) are strong and operations are mature (flat learning), the optimal allocation is unique and stable, simplifying governance and negotiation with the assembly partner.

Proposition 3.

First-Order Condition and Elasticity Balance at an Interior Optimum.

Proof of Proposition 3.

If is an interior solution, then . Let , then Define the cost shares and elasticities . It follows that .

Equivalently, □

- Managerial Insight: At the optimum, the marginal (share-weighted) increase in defensive and environmental costs exactly balances the marginal (share-weighted) savings from operational terms. This provides a clear negotiation rule for setting : adjust it until both sides of the equation are equal.

Proposition 4.

Strategic Trade-Off Interpretation.

- Define elasticity terms: , , , .

- At the optimal allocation rate , the total marginal elasticity satisfies .

Proof of Proposition 4.

At any interior optimum , the first-order condition for total cost minimization is:

Rearranging terms yields:

Multiply both sides by , and define cost shares:

This gives:

, where denotes the operational elasticity of setup cost.

Under the realistic assumption that setup cost curvature is negligible near the optimum ) and that all cost shares are approximately equal, the above simplifies to:

Thus, the unweighted balance holds when marginal setup effects are small and relative cost weights are uniform. □

- Managerial Insight: At the equilibrium allocation, the marginal increase in strategic and environmental costs is balanced by the marginal savings in production and inventory costs. This condition characterizes a Pareto-efficient allocation between upstream and midstream stages, reflecting both economic rationality and sustainability compliance.

4. Application and Numerical Analysis

4.1. Application Scenario: Green Electronics Manufacturing Alliance

To illustrate the practical application of the proposed model, consider a green electronics manufacturing alliance between two vertically integrated firms: Firm A, an upstream semiconductor component manufacturer, and Firm B, a midstream assembly plant producing energy-efficient consumer electronics. This partnership operates under the regulatory framework of the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which imposes taxes on embedded carbon emissions. Within this framework, both firms must coordinate production efficiency and environmental compliance while facing growing market competition.

Firm A, located in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, manufactures high-precision chips whose setup and calibration require extensive learning and accumulated experience. However, workforce turnover and equipment maintenance can diminish this experience, resulting in a forgetting effect. Firm B, located in Eastern Europe, completes the final assembly and distribution of finished goods. Although its operations are less technically demanding, they are highly sensitive to demand fluctuations and seasonal labor variations, which similarly influence learning and forgetting dynamics. These behavioral factors influence the setup cost (SC) and production cost (PC) functions in the model, determining how experience retention affects overall system efficiency.

Meanwhile, the competitive landscape evolves according to a nonhomogeneous Poisson process (NHPP), reflecting the accelerating entry of rival firms as technology diffuses and market transparency improves. Defensive expenditures—such as collaborative R&D and marketing—increase with the number of entrants and are represented by the defensive cost (DC) term. At the same time, environmental taxation introduces an additional layer of complexity: Firm A’s energy-intensive chip production incurs higher carbon taxes, while Firm B faces indirect costs related to logistics and assembly energy use. Consequently, the cost-allocation rate (Φ) becomes a strategic lever. A higher Φ shifts more production and environmental responsibility to the assembler, reducing upstream exposure but increasing coordination costs; conversely, a lower Φ allows the manufacturer to retain control over emission-intensive stages but raises its own financial burden.

In this scenario, the alliance employs the total-cost minimization model to determine the optimal allocation, , which balances economic efficiency, competitive resilience, and environmental responsibility. As carbon tax rates or competitor intensity change, the equilibrium allocation shifts accordingly—demonstrating how dynamic learning, forgetting, and sustainability considerations collectively influence cost-sharing decisions. This case highlights that cost allocation is not merely an accounting mechanism but a strategic tool for managing knowledge, competition, and environmental compliance in modern manufacturing systems.

To quantitatively represent this scenario, the simulation employs the parameter configuration summarized in Table 2. These parameters characterize a medium-scale production system with moderate learning, mild forgetting, and steady market competition. They correspond directly to the notation and cost functions introduced in Section 3 and are implemented using the Python version 3.8.0.-based computational model.

Table 2.

Parameter Configuration for the Alliance Scenario.

4.2. Computational Results

Using the parameter configuration presented in Table 1, the total cost function was evaluated and numerically optimized over the interval . The optimization was performed using the bounded scalar minimization routine implemented in the minimize_scalar function from the SciPy optimize package in Python. This method is widely used in scientific computing and is well suited for one-dimensional convex optimization. Since our theoretical analysis establishes that the total cost function is convex in , no special parameter tuning was required, and the solver reliably returned the unique global minimizer.

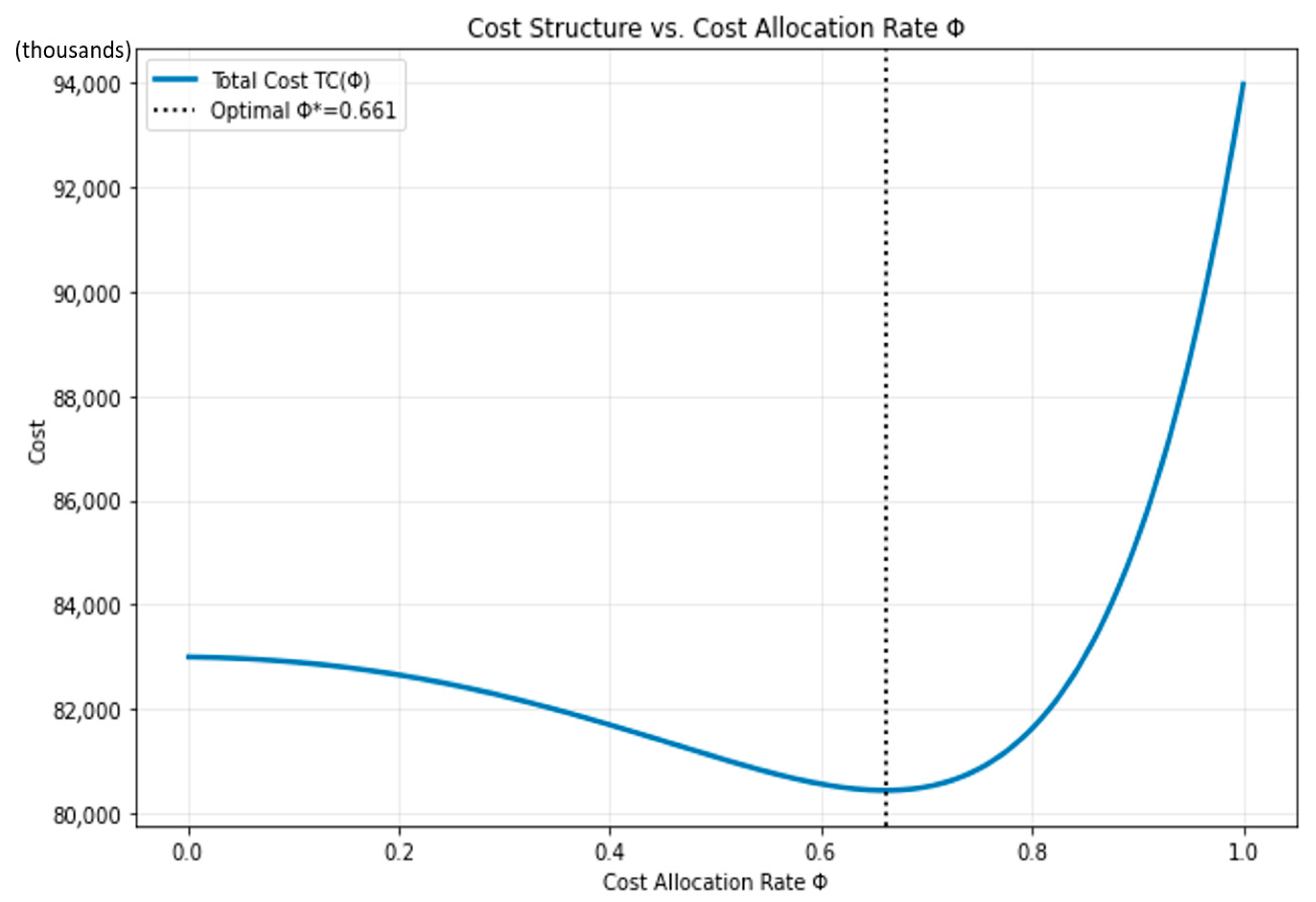

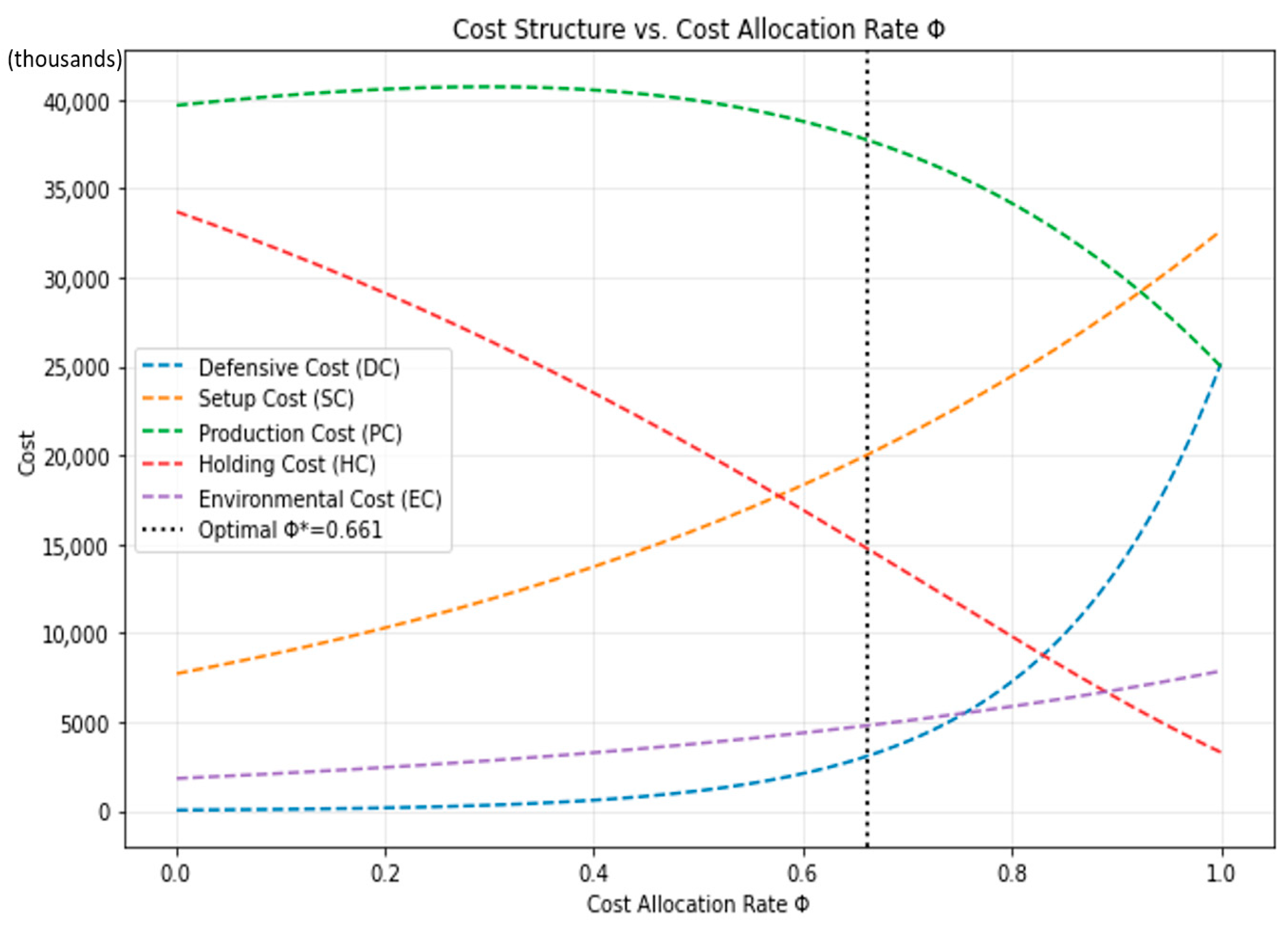

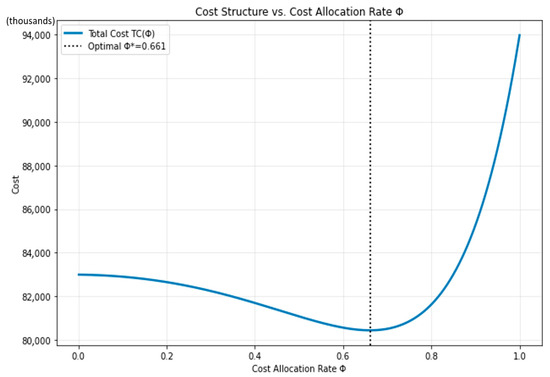

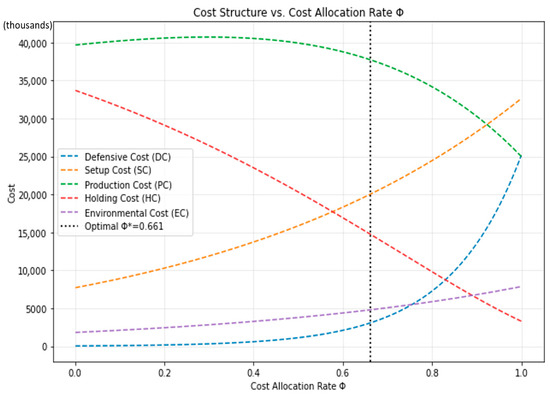

The resulting optimal cost-allocation rate and the corresponding minimum total cost were determined to be = 0.661 and = $80,440,900, respectively. Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the total cost and individual cost components as functions of the allocation rate, while Table 3 provides additional numerical details.

Figure 2.

Total Cost vs. Cost Allocation .

Figure 3.

Individual Costs (DC, SC, PC, HC, EC) versus Cost Allocation .

Table 3.

Total Cost and Individual Costs (DC, SC, PC, HC, EC) versus Cost Allocation .

The simulation confirms that exhibits a well-defined convex structure across the entire feasible domain. As shown in the computational visualization (see Figure 2 and Figure 3), the total cost curve decreases steadily as the allocation rate Φ rises from 0 to approximately 0.38, after which it begins to increase at an accelerating rate. This pattern reflects the economic trade-off between risk-sharing efficiency and escalating defensive costs. At low allocation levels, the upstream firm (Firm A) bears most of the production and environmental burden, leading to overinvestment in defense and excessive holding costs. Conversely, at high allocation levels, the midstream firm (Firm B) becomes overexposed to production variability, resulting in coordination inefficiencies and rising setup costs. The optimal point, = 0.66, therefore represents a balanced cost-sharing equilibrium between the two firms.

At the optimal rate, the decomposition of total cost reveals how each component contributes to system efficiency. The defensive cost (DC) and production cost (PC) together account for more than half of the total expenditure, indicating that market competition and production learning dominate the alliance’s financial landscape. The setup cost (SC) and holding cost (HC) represent smaller yet stabilizing portions, reflecting the incremental effects of experience accumulation and inventory management. Although numerically smaller, the environmental cost (EC) remains a significant factor that alters the slope of the total cost curve, introducing a sustainability constraint into the economic equilibrium.

Further analysis of the numerical second derivative confirms strict convexity over the interval (0, 1), with the minimum curvature value remaining positive. This validates the theoretical assumption that the total cost function is convex under the given parameter conditions, ensuring the uniqueness and stability of the optimal solution . From a managerial perspective, this convexity implies that small deviations around the optimal allocation result in only marginal changes in total cost—an important property for contractual robustness, as it allows minor negotiation flexibility without destabilizing the cost structure.

The shape of each component cost curve offers deeper insight into the alliance’s operational dynamics. The defensive cost curve increases exponentially with Φ, reflecting the convex nature of joint defensive investment. The setup and production cost curves exhibit concave–convex behavior, capturing the transition from early-stage learning—where marginal costs decline—to steady-state operation, where costs stabilize. The holding cost follows an approximately quadratic form, as excess inventory becomes increasingly penalizing when production exceeds demand. Finally, the environmental cost rises monotonically with , indicating that greater production allocation to the assembler amplifies emissions-related expenses.

Overall, the computational results demonstrate how the interplay among learning–forgetting behavior, competitive intensity, and environmental taxation jointly determines the optimal cost-sharing ratio. The alliance achieves its most efficient equilibrium when both firms contribute proportionally to production and sustainability investments, maintaining competitiveness without overburdening either party. Practically, this equilibrium corresponds to a scenario in which Firm A assumes responsibility for the strategic, high-emission production stages, while Firm B manages downstream assembly and logistics under a moderately shared cost framework.

The next subsection extends this analysis through sensitivity experiments that explore how variations in market intensity, learning rate, and carbon taxation affect the equilibrium . These results offer managerial insights into how firms can adapt their cost-sharing policies in dynamic and uncertain industrial environments.

The supporting information of the computation can be found in the Supplementary Materials of this article (https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math13233760/s1).

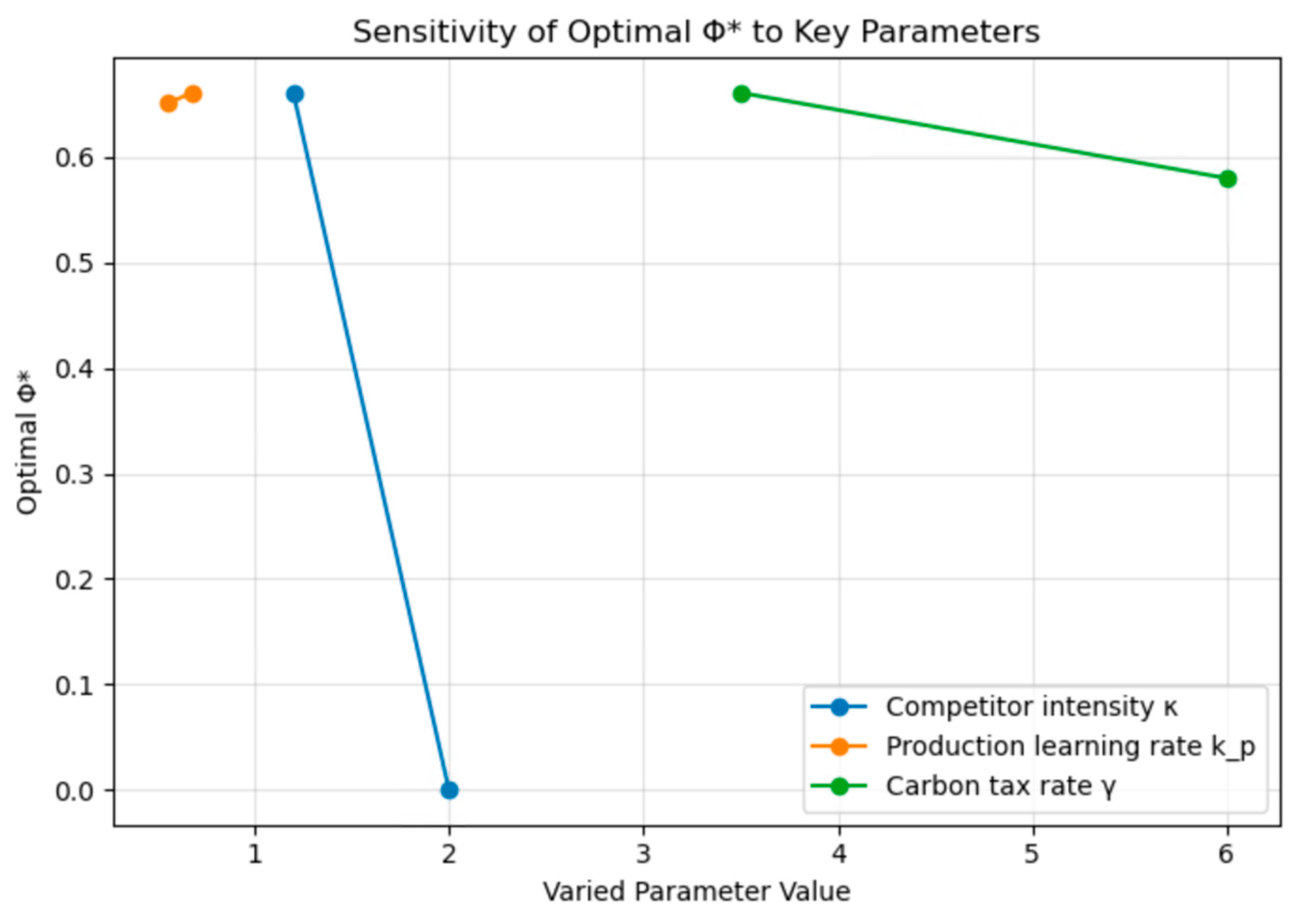

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

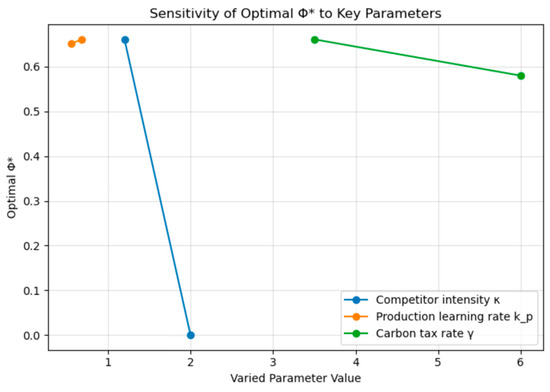

The sensitivity experiments evaluate how variations in three critical parameters—competitive intensity (), production learning rate (), and carbon tax rate ()—influence the optimal cost allocation rate and the corresponding minimum total cost. The results, summarized in Table 4 and visualized in Figure 4, reveal distinct yet economically consistent adjustment patterns in the alliance’s equilibrium structure.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analysis of Key Parameters.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity of Optimal Value of Φ to Key Parameters.

When competitive intensity increases (: 1.2→2.0), the optimal allocation rate declines sharply, nearly reaching zero. This indicates that in highly competitive markets, the downstream assembler reduces its cost participation, shifting a greater share of financial responsibility upstream. Such a reallocation prevents redundant defensive expenditures across firms and allows the upstream producer to centralize investments in innovation and market defense. From a managerial perspective, this result underscores the need for flexible contract mechanisms that can automatically adjust the cost-sharing ratio in response to market entry intensity or competitive threats. It suggests that dynamic cost governance—rather than fixed cost distribution—can help alliances maintain efficiency under fluctuating market conditions.

The variation in the production learning rate (: 0.68→0.55) has only a mild effect on both and total cost. This stability implies that once production processes have matured and learning saturation is reached, additional improvements in learning retention contribute less to cost optimization. Therefore, managerial focus should shift from incremental learning investments toward maintaining process reliability and integrating complementary strategies, such as defensive coordination or environmental adaptation. In other words, organizational learning continues to serve as a stabilizing foundation, but its marginal influence diminishes as technological maturity increases.

Changes in the carbon tax rate (: 3.5→6.0) produce a moderate increase in total cost and a downward adjustment in . This reflects an economically rational response to environmental regulation: as emission costs rise, the upstream producer—who directly controls production and emission processes—absorbs a larger share of the financial burden. The result reinforces the role of environmental policy as a structural factor in alliance governance. Firms should therefore integrate carbon pricing or emission metrics into their cost-sharing agreements, ensuring that sustainability incentives are aligned with operational responsibilities.

Overall, the revised managerial insights suggest that the proposed framework provides a practical decision-support tool for coordinating industrial alliances under dynamic conditions. Competition and environmental factors emerge as the dominant drivers of cost redistribution, while learning functions primarily as a stabilizing element. The model’s convex and well-behaved cost surface ensures that moderate deviations around do not cause disproportionate losses, granting firms flexibility in negotiation and implementation. Consequently, alliances that institutionalize adaptive, data-driven cost-sharing mechanisms—responsive to competition, learning dynamics, and carbon regulations—are better positioned to sustain both economic efficiency and environmental accountability over the long term.

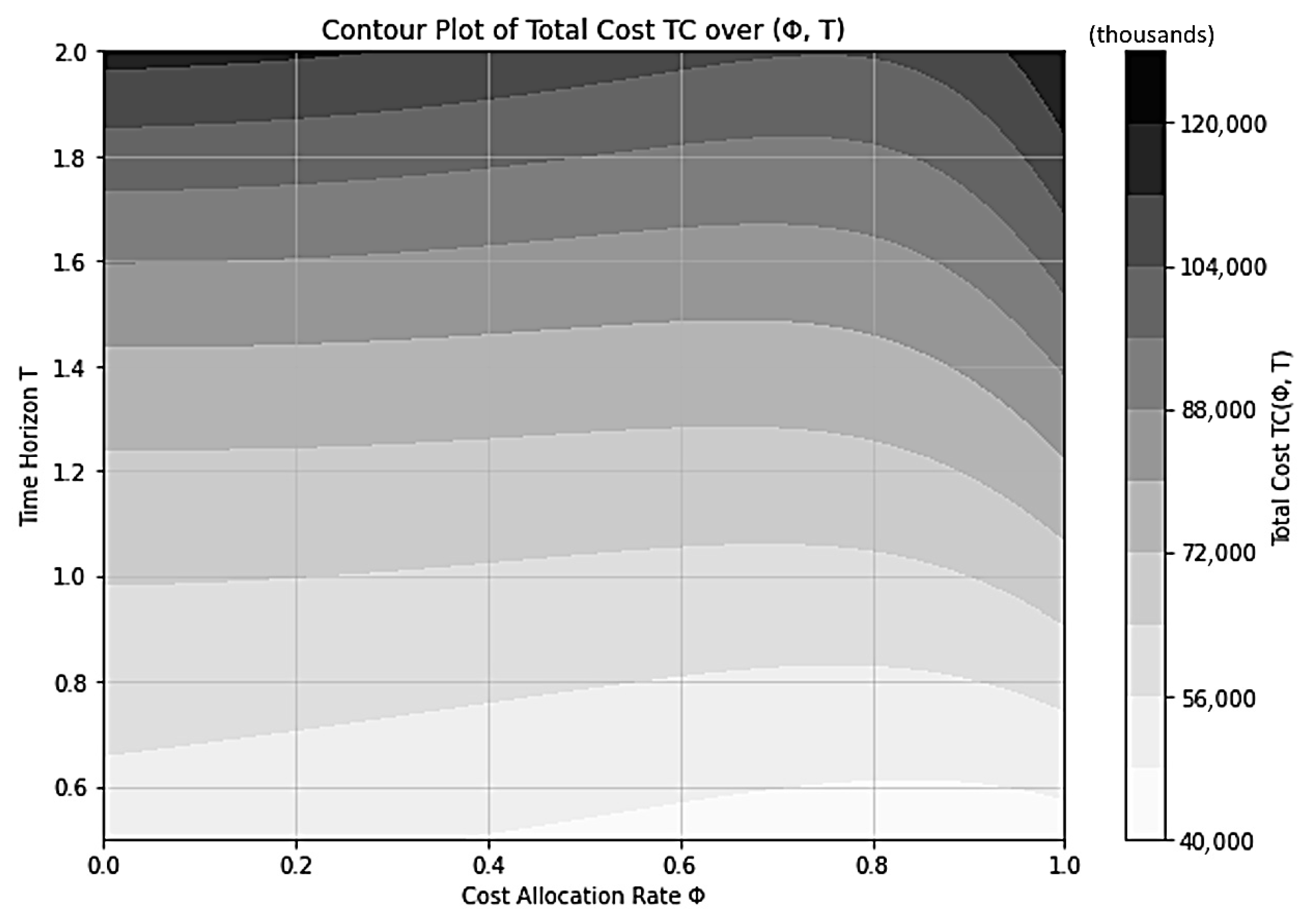

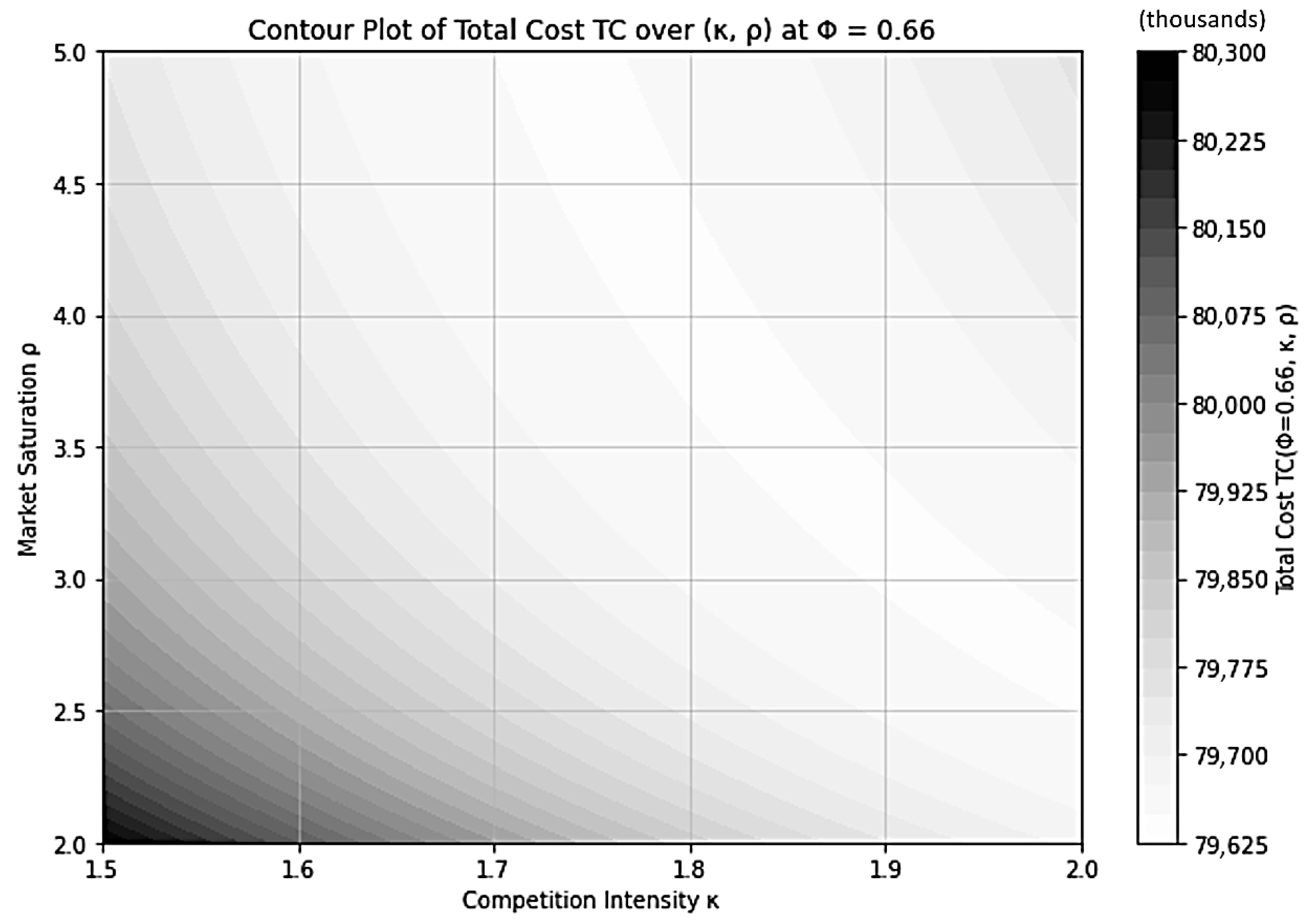

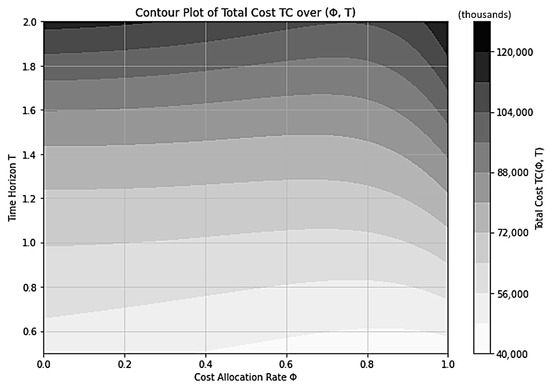

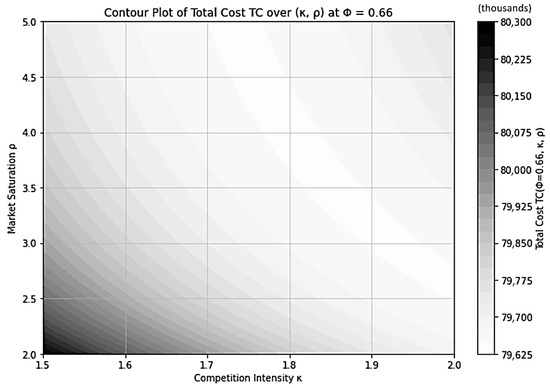

Moreover, the contour plots shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6 further illustrate the structural characteristics of the total cost surface under the updated parameter set.

Figure 5.

Contour Plot of Total Cost over Cost Allocation Φ and Production Run Length T.

Figure 6.

Contour Plot of Total Cost over Parameters , .

Figure 5 illustrates the contour plot of the total cost TC(Φ,T) as a joint function of the cost allocation rate (Φ) and the planning horizon (T). The contour surface exhibits a smooth convex pattern that gradually rises with longer horizons, indicating that total cost increases as the planning window expands. The lightest region, representing the minimum cost zone, forms a shallow ridge around ≈ 0.6–0.8, suggesting that the optimal allocation ratio remains relatively stable across the examined time horizon T ∈ [0.6, 2.0]. This stability implies that the alliance’s cost-sharing equilibrium is robust with respect to temporal variations—moderate extensions or contractions of the planning period do not significantly alter the optimal allocation rate. From a managerial perspective, such time-invariant behavior allows firms to maintain consistent cost-sharing agreements without frequent renegotiation, even as production cycles evolve. The convex and well-behaved structure of the contour map further validates the model’s theoretical assumption of a unique, stable minimum, reinforcing both analytical soundness and practical applicability.

Figure 6 illustrates the contour distribution of the total cost at a fixed allocation rate of Φ = 0.66. The contour surface reveals that cost levels vary smoothly across the joint space of competition intensity () and market saturation (). The lighter central region represents the lowest total cost zone, indicating the most efficient combination of moderate competitive intensity and market maturity. In contrast, the darker regions located in the lower-left and upper-right corners correspond to higher total cost areas. The pattern suggests that when both market saturation and competition intensity deviate from moderate levels—either through overly aggressive competition with limited market reach (lower-left) or excessive market expansion under strong rivalry (upper-right)—the system experiences a rise in total cost. This reflects the nonlinear interplay between competitive pressure and market development: alliances operating in highly contested or underdeveloped markets tend to face cost inefficiencies due to defensive overinvestment or underutilized capacity. Managerially, this contour distribution highlights that maintaining a balanced level of market competition and diffusion is critical to sustaining cost efficiency. Alliances can minimize total expenditure by avoiding extremes in competitive intensity or saturation, instead targeting the intermediate region where cooperative learning and defensive coordination yield the greatest stability and economic resilience.

4.4. Managerial Insights

The numerical and sensitivity analyses demonstrate that the proposed cost allocation framework—integrating learning–forgetting behavior, market competition, and environmental taxation—serves not only as an analytical optimization tool but also as a strategic instrument for alliance governance under uncertain and dynamic conditions. The results show that the optimal allocation rate ≈ 0.66 is not fixed; it adjusts systematically as firms respond to shifts in competition, learning retention, and environmental regulation. This reinforces the principle that cost sharing should be managed as a dynamic coordination variable rather than a static contractual parameter.

When competitive intensity () increases, the optimal allocation rate falls sharply. This downward movement indicates that stronger competition prompts the upstream producer to internalize a greater portion of the total cost. By absorbing more financial responsibility, the upstream firm strengthens its defensive capabilities and innovation capacity, thereby reducing redundancy in downstream operations. From a managerial standpoint, such a mechanism illustrates how cost sharing can operate as a self-regulating process—transferring the financial burden upstream when market turbulence intensifies to preserve overall alliance efficiency.

The sensitivity analysis of the production learning rate () further emphasizes the stabilizing role of accumulated experience. As learning retention improves (i.e., forgetting declines), decreases slightly and total cost remains nearly constant. This suggests that once production processes become mature, additional learning improvements yield diminishing economic returns. Managerially, this means that firms should maintain learning systems as a stability safeguard rather than as the primary lever of cost reduction, focusing instead on coordination and environmental adaptation when returns to learning flatten.

The impact of the carbon tax rate () reveals the coupling between environmental policy and economic behavior. As carbon pricing rises, decreases while total cost increases moderately, implying that the upstream producer—responsible for emissions—assumes a larger cost share. This shift encourages cleaner technologies and sustainable practices, showing that properly designed cost-sharing contracts can internalize environmental incentives without undermining economic efficiency.

Finally, the convex and stable form of the total cost function ensures that small deviations around lead to only minor cost differences. This property enhances the robustness of negotiations and enables flexible contractual adjustments. Managers can therefore use as a benchmark for adaptive negotiation, maintaining fairness and stability even when market or policy conditions fluctuate.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a comprehensive cost-allocation framework that explicitly incorporates learning and forgetting effects, market competition, and environmental constraints into a unified analytical model. Departing from conventional static approaches, the proposed formulation captures the evolving nature of production efficiency and strategic interactions among cooperating firms. By introducing an NHPP to characterize competitive entry and embedding learning–forgetting dynamics within setup and production cost functions, the model offers a realistic representation of how industrial alliances adapt under technological diffusion and environmental regulations.

The theoretical analysis demonstrates that the total cost function remains convex under reasonable parameter conditions, ensuring the existence of a unique optimal cost allocation rate . This mathematical property provides the model with both analytical tractability and managerial interpretability. The empirical application—based on the Green Electronics Manufacturing Alliance—illustrates how the framework can be used to balance economic efficiency, defensive investment, and environmental compliance in practice. Through simulation, the optimal allocation was shown to respond dynamically to changing external and internal factors, confirming that cost sharing is not a static accounting rule but a strategic decision variable shaped by organizational learning and policy environments.

The sensitivity analyses further enhance the understanding of the model’s managerial relevance. Increases in competitive intensity encourage greater downstream cost participation, enabling upstream firms to conserve resources for innovation. In contrast, improved learning efficiency allows for greater internalization of costs without sacrificing competitiveness, while higher carbon tax rates shift responsibility toward emission-intensive stages, promoting green adaptation. Collectively, these results highlight that the optimal allocation ratio evolves endogenously, reflecting the alliance’s capacity for self-adjustment in response to changing market, technological, and regulatory environments.

From a managerial perspective, the findings suggest that firms engaged in collaborative production networks should adopt adaptive cost-sharing mechanisms that evolve over time, rather than relying on fixed contractual proportions. The proposed framework provides a quantitative foundation for such adaptive governance, enabling partners to negotiate, evaluate, and periodically recalibrate cost structures based on measurable operational and environmental parameters. Moreover, by linking cost allocation to learning and sustainability, the model contributes to the broader discussion on how industrial cooperation can align economic performance with ecological responsibility. However, applying the model in practice may face challenges such as accurately estimating learning–forgetting parameters, collecting reliable emission and cost data, coordinating information sharing across firms, and aligning incentives among partners with different strategic priorities. These practical constraints highlight the importance of organizational readiness and data maturity in real-world implementation.

Future research could extend the current framework in several promising directions. Incorporating multi-period dynamics would allow for a deeper exploration of cumulative learning and policy adaptation over time. Introducing stochastic elements into demand, cost, or competitive processes could better capture uncertainty and risk in global supply chains. Additionally, integrating game-theoretic perspectives could reveal strategic negotiation behaviors under conditions of asymmetric information and bargaining power. Moreover, conducting real-world case studies to empirically validate the model’s parameters and managerial insights would meaningfully strengthen its practical relevance and ensure that the proposed mechanisms reflect industry conditions. Finally, empirical validation using firm-level or industry-level data would enhance the model’s applicability and support its calibration for real-world decision-making. Further studies may also explore how digital manufacturing systems, AI-driven learning estimation, and real-time carbon monitoring can complement the proposed analytical structure, thereby improving the feasibility of industrial deployment.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates that cost allocation, when enhanced by learning, forgetting, and environmental factors, evolves into a strategic coordination mechanism that aligns efficiency, competitiveness, and sustainability. The proposed model provides both theoretical insight and practical guidance for managers aiming to navigate complex production networks in a rapidly changing global economy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math13233760/s1. Supporting information includes the dataset corresponding to Table 3 and the complete set of computational programs used for the mathematical calculations presented in Section 3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; Data Curation, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; Formal Analysis, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; Funding Acquisition, M.-N.C.; Investigation, C.-C.F.; Methodology, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; Project Administration, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; Resources, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; Supervision, M.-N.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation and the Guangdong Soft Science Foundation, China [grant number 2024A0505050043].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ho, J.W.; Huang, Y.S. Cost allocation with learning and forgetting considerations in a monopolistically competitive market. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2010, 41, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.Y.; Givi, Z.S. Imperfect production process with learning and forgetting effects. Comput. Manag. Sci. 2015, 12, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarfi, R.; Jaber, M.Y.; Glock, C.H. Pricing and inventory decisions in a dual-channel supply chain with learning and forgetting. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 136, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, M.; Afshari, H.; Jaber, M.Y.; Searcy, C. Learning and forgetting interactions within a collaborative human-centric manufacturing network. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 313, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.C.; Glock, C.H. A closed-loop supply chain with stochastic product returns and worker experience under learning and forgetting. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 6760–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Leung, J.Y.T. Worker assignment and production planning with learning and forgetting in manufacturing cells by hybrid bacteria foraging algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 96, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, F.F.; Deuse, J. Modelling forgetting due to intermittent production in mixed-model line scheduling. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2024, 36, 503–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xie, F.; Hall, N.G. Sequencing with learning, forgetting and task similarity. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 325, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercan, H.; Deibert, P.; Meisen, T. Continual learning of neural networks for quality prediction in production using memory aware synapses and weight transfer. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenzi, F.; Mossa, G.; Mummolo, G.; Romano, V.A. Workforce aging in production systems: Modeling and performance evaluation. Procedia Eng. 2015, 100, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rerkjirattikal, P.; Wanwarn, T.; Olapiriyakul, S. Heuristics for noise-safe job-rotation problems considering learning-forgetting and boredom-induced job dissatisfaction effects. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, O.; Giri, B.C. A new approach to deal with learning in inspection in an integrated vendor-buyer model with imperfect production process. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 131, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.C.; Masanta, M. Developing a closed-loop supply chain model with price and quality dependent demand and learning in production in a stochastic environment. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2020, 7, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Lei, Y.; Fu, X.; Lin, C.H.; Chang, C.H. How can manufacturers promote green innovation in food supply chain? Cost sharing strategy for supplier motivation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 574832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleizadeh, A.A.; Niaki, S.T.A.; Alizadeh-Basban, N. Cost-sharing contract in a closed-loop supply chain considering carbon abatement, quality improvement effort, and pricing strategy. RAIRO Oper. Res. 2021, 55, S2181–S2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; He, S.; He, Z. Information sharing under different warranty policies with cost sharing in supply chains. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 27, 1550–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Zhang, J.; Tang, W. Cartelization or cost-sharing? Comparison of cooperation modes in a green supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Fan, Z.P.; Cao, B.B. Cost-sharing strategy for carbon emission reduction and sales effort: A Nash game with government subsidy. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2020, 16, 1559–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Lai, Y.; Li, L. Research on incentive strategies and cost-sharing mechanisms for cross-regional pollution control. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Kong, W. The effect of government subsidies on cooperative green innovation of supply chains from the perspective of cost sharing. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2025, 40, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y. Impact of carbon tax on enterprise operation and production strategy for low-carbon products in a co-opetition supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Li, Y.; Mao, H.; Miao, Z. Firms’ production and green technology strategies: The role of emission asymmetry and carbon taxes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lang, L.; Hu, B.; Shi, L.; Huang, B.; Zhao, Y. Emission reduction decision of agricultural supply chain considering carbon tax and investment cooperation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chi, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X. The impact of carbon tax policy on residents’ welfare of China and its heterogeneity under the carbon neutrality goal: A CGE model-based analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Ji, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. Research on the application of conjoint analysis in carbon tax pricing for the sustainable development process of China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kang, J.; Sun, H.; Pang, G. Impact of carbon abatement policies on cross-border supply chain remanufacturing: The role of import quotas. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 1281–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Tan, J.; Dai, J. Analysis of decision-making in a green supply chain under different carbon tax policies. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Wang, K.; Lin, J.; Qian, Y. Carbon tax vs. carbon cap-and-trade: Implementation of carbon border tax in cross-regional production. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 274, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamipoor, R.; Sepehriyar, A. Promoting green supply chain under carbon tax, carbon cap and carbon trading policies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4901–4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Vortia, M.P.; Xiao, G.; Yang, J. Carbon policies and liner speed optimization: Comparisons of carbon trading and carbon tax combined with the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, S.; Aşıcı, A.A.; Yeldan, A.E. Potential effects of the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism on the Turkish economy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 8162–8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Pei, J. Carbon border adjustment mechanism: A systematic literature review of the latest developments. Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogdu, E. The carbon border adjustment mechanism: Opportunities and challenges for non-EU countries. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2025, 14, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.Q. Optimal joint decisions of production and emission reduction considering firms’ risk aversion and carbon tax rate. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 1189–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.C.; Hsu, C.C.; Chu, C.W. Enhancing efficiency in supply chain management: A synergistic approach to production, logistics, and green investments under different carbon emission policies. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2025, 16, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Carbon tax or low-carbon subsidy? Carbon reduction policy options under CCUS investment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).