1. Introduction

Generally, a competitive programming problem has a small number of algorithmic, usually two, three, or at most five. However, for an algorithmic approach, there can be many implementations depending on the programming language (e.g., C or C++), the data structures used, or the code style. In our context, we consider algorithmic strategies and implementations that are efficient and whose performance, in terms of running time and memory usage, is sufficient to achieve accept on the virtual judge. Two algorithmic strategies are considered different if the data structures/methods used are different. For example, two different algorithmic strategies for the problem of finding if multiple elements are in an array could be: (1) sort the array + binary search, (2) use a hash data structure. As a counterexample for the same problem, the following two algorithmic strategies are the same: (1) merge sort + binary search, (2) heap sort + binary search, because both of them involve sorting and binary search.

Thus, the task that we are trying to solve is the following: Given a number

K of distinct algorithmic strategies for a set of correct solutions to a problem, map each solution to its corresponding algorithmic strategy. To evaluate how various methods perform on the given task, we need a set of problems for which we know the distinct algorithmic solutions. Having this in mind, we created a dataset, AlgoSol-15 [

1], containing 15 competitive programming problems with multiple distinct algorithmic solutions. The dataset was created by having two expert competitive programmers annotate each participant’s submission to the correct algorithmic solution.

Multiple practical applications could benefit from the given task: (1) Education—especially but not limited to competitive programming, our work allows the possibility to cluster various solutions to a given problem in a contest by the algorithmic solution, thus enabling faster insights into alternative or even novel ways to solve a given problem. (2) AI-assisted coding analysis—improves the suggestions given by an LLM with alternative algorithmic solutions to a given implementation. The practitioner could select a more fitting implementation that still solves the problem correctly. (3) Augmented Retrieval Generation—enhances the knowledge database with tags related to the algorithmic solution used in a specific problem. When doing retrievals for various queries, one could also consider distinct algorithmic solutions for the same problem.

As key ingredients for solving the task, we have employed seven embedding methods and three unsupervised methods to identify solution clusters. One method is based on voting and uses a co-training data-analysis pipeline. The results are encouraging: for almost every problem in the dataset, we identified a method and a setup (i.e., embedding and clustering algorithm) for which the F1 macro score generally exceeds 0.9.

The current work represents an extended version of [

2]. We increased the number of problems (from 10 to 15) in the dataset and added more embeddings (from 3 to 7) for code representation. We also improved the efficiency of the unsupervised method by employing a heuristic-based algorithm. We investigated whether the current algorithm could also be used to determine the optimal

K (i.e., the number of distinct algorithmic strategies) for a given problem. Finally, the experiments were performed on all combinations of embeddings using three pattern detection algorithms (i.e., hard clustering, Multiview Spectral Clustering, and a custom-designed voting algorithm). Therefore, the contributions of the work are: (1) A publicly available dataset [

1] with correct solutions to 15 problems from Infoarena (Infoarena,

https://infoarena.ro/ (Last accessed 10 August 2025)) online judge. (2) A data-analysis pipeline consisting of seven code-embedding methods and three clustering algorithms for unsupervised training. (3) An evaluation of how informative each embedding method is based on the number of samples provided using the XGBoost model. (4) Improving the unsupervised method by converting the problem into a tree where we explore paths heuristically, thus improving the algorithm in practice. (5) Extending the comparison to determine the correct number of distinct algorithmic strategies with ChatGPT 4o and 4.1. (6) Using the unsupervised method to determine the optimal

K by employing the silhouette method on the resulting dataset and comparing it with the silhouette method on the original dataset.

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows: in

Section 2, we review the main works that address the problem of analyzing the source-code competitive programming solutions; in

Section 3, we thoroughly present the data-analysis pipeline with its key ingredients, such as code-embedding methods, clustering algorithms, the proposed unsupervised voting algorithm, and the evaluation methodology.

Section 4 presents the experimental results for various setups of embedding methods, clustering algorithms, and estimators. Lastly,

Section 5 discusses the results, draws conclusions, and provides several lines for future research.

2. Related Work

One of the most recent advances in competitive programming source-code analysis is represented by AlphaCode [

3] and AlphaCode 2 [

4]. With an extensive dataset, efficient transformer-based architectures, and model sampling and filtering capabilities, the results are promising: AlphaCode ranked top 54.3% on the Codeforces platform (Codeforces platform,

https://codeforces.com/ (last accessed 10 August 2025)) after ten contests with over 5000 participants each, while AlphaCode 2 performed better than 85% of the participants. The big leap between AlphaCode and AlphaCode 2 is attributed to Google’s foundation model, Gemini, demonstrating that LLMs can play a crucial role in improving a particular algorithm.

Recent works [

5] evaluated the similarity between generated codes from AlphaCode and human code and compared their performance (i.e., running time, memory usage, and readability). The findings were that the generated code is quite similar to human code (i.e., the average maximum similarity score is 0.56) and could be identical for simple problems. The generated and human-coded code performed quite similarly in terms of runtime and memory usage. Still, in TLE (time limit exceeded) cases from high-difficulty problems, AlphaCode introduced unnecessary nested loops in the generated source code.

As an alternative to Alpha Code 2, which makes use of a fine-tuned version of Gemini Pro on CodeContests Dataset [

3] and generates over 1 million samples per problem, AlphaCodium [

6] shows that a carefully crafted flow specifically tailored for competitive programming on a general LLM model can obtain similar results with fewer resources (∼ 23–25 calls).

Another exciting line of work in competitive programming is bug fixing and program fixes. As one of the goals of competitive programming is to train students to write bug-free code, fixing bugs represents one of the main activities towards getting a solution accepted on a virtual judge. All the bug-fixing experiences from a competitive programming context constitute valuable information that was compiled into a dataset used to build the FixEval tool [

7]. Therefore, datasets and models from a competitive programming context can be used for software engineering tasks such as verdict-conditioned code repair, verdict prediction, and chain edit suggestion.

The availability of various code embeddings allows code analysis and synthesis using NLP techniques. With this relatively new approach, the synthesis of short Python programs from natural-language descriptions has been tackled in [

8] on 974 simple programming tasks. The tasks were designed to be solvable by entry-level programmers, given that natural-language descriptions are typically one sentence each and the average number of lines of code is 6.8. Regarding competitive programming, the authors have stated that problem statements that are written in a style that obfuscates the underlying algorithms significantly reduce performance.

Very recently, ChatGPT (ChatGPT: Optimizing Language Models for Dialogue,

https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/ (last accessed 10 August 2025)) has been used to solve the

Factorial and Multiple problem (

https://atcoder.jp/contests/abc280/tasks/abc280_d (last accessed 10 August 2025)) after several interactions (

https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/109815 (last accessed 10 August 2025)). Among other tasks (e.g., answering questions, creating content, restyling, writing, explaining, and tutoring), the newest and previously impossible tasks regarding writing and debugging code, manipulating data (i.e., understanding JSON), or even taking SATs. The key distinction between ChatGPT and Google is that ChatGPT is trained on data and does not operate as an Internet index. Therefore, due to its very nature, ChatGPT has two limitations: one related to its training and the other to its tendency to provide wrong answers.

Another large-scale system that translates natural language to source code is OpenAI Codex [

9], which has been used to (1) generate solution code as output from a natural-language description of a programming problem, (2) explain (in English) source code, or (3) translate source code between programming languages and more. For typical introductory programming problems, OpenAI Codex outscores most students [

10]. The most popular industrial application that is used in AI-assisted programming is GitHub Copilot (GitHub Copilot,

https://github.com/features/copilot/ (last accessed 10 August 2025)). Currently, efforts are focused on studying Copilot’s capabilities for generating (and reproducing) correct and efficient solutions to fundamental algorithmic problems and on comparing Copilot’s proposed solutions with those of human programmers on a set of programming tasks [

11]. Having the same goal of evaluating GitHub Copilot, an empirical study aims to determine whether different but semantically equivalent natural-language descriptions yield the same recommended function [

12].

The success of AI in programming has also led to the concepts of Vibe Coding and Agentic Coding. While Vibe Coding follows a prompt-based, human-in-the-loop approach, Agentic Coding focuses on autonomous software development through agents with minimal human interaction. In [

13], the authors conduct an exhaustive comparison of Vibe Coding and Agentic Coding, exploring their architectures, benefits, and limitations.

Besides our task of determining distinct algorithmic solutions in competitive programming, there are other tasks explored as well. For example, one could train a model to predict the tags (e.g., greedy, dynamic programming, etc.) and difficulty of a specific problem [

14] or train a model to match problem statements with their editorial [

15]. There is also research in the capabilities of LLMs to act as problem solvers by generating new problems with tests and solutions based on a seed problem [

16].

3. Materials and Methods

A particular aspect of the task is that, in competitive programming, a problem usually has a small number of algorithmic strategies, which allows manual labeling. This has two implications: (1) we face a classification problem or an unsupervised learning situation with a known and small number of clusters (i.e., the number of solving strategies as in

Table 1), we may build a labeled dataset for validation purposes. Therefore, we can consider that for a particular problem, we know

K (i.e., the number of distinct algorithmic strategies). (2) The task is to correctly determine to which of these approaches each solution belongs. Given that we do not have any labels for our instances (i.e., solutions or implementations to a given problem), we are clearly in an unsupervised learning scenario.

Preprocessing. The first step in the pipeline is the preprocessing of source files. Depending on the embedding method used, the following steps may be performed: (1) delete the #include directives; (2) delete comments; (3) delete unused functions; (4) replace all macro directives; (5) delete all apostrophe characters; (6) delete all characters that are not ASCII; (7) tokenise the source code.

Embedding computation. To generate the embeddings, we use the following models: Word2Vec (W2V) [

17], Tf-Idf [

18], SAFE [

19], UniXcoder [

20], CodeT5+ [

21], text-embedding-3-small (OpenAI), and mistral-embed (MistralAI).

W2V uses the tokens for each source file after preprocessing. Based on the obtained tokens, we build a neural network to predict the current token from nearby tokens using a C-BOW architecture [

17]. The algorithm uses a window of 5 tokens, and the embedding is a 128-dimensional vector. The resulting source-code embedding is the average of the token embeddings that make up the solution.

Tf-Idf algorithm uses the tokens obtained for each source code after preprocessing. These tokens are filtered by removing stop words and selecting words that match a specific regular expression. The output of Tf-Idf algorithm is a matrix whose number of columns is the cardinality of the vocabulary (i.e., the number of distinct filtered tokens).

SAFE uses only the binary code obtained after compilation of the solution source code. The pretrained SAFE model is used to compute one embedding for each function in the source code. The dimension of the obtained vector is 100, and the embedding of a solution is the average of the embeddings of all subprograms (i.e., functions or methods) from the source code.

UniXcoder was pretrained using a flattened AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) and code comments. The model computes one embedding for each function in the source code. The dimension of the obtained vector is 768, and the embedding of a solution is the average of the embeddings of all subprograms from the source code.

CodeT5+ uses an encoder-decoder architecture with a mixture of pretraining objectives that reduces the pretrain-finetune discrepancy. The model computes one embedding for each function in the source code. The dimension of the obtained vector is 256, and the embedding of a solution is the average of the embeddings of all subprograms from the source code.

OpenAI and MistralAI embedding models are used to investigate how much the size of the embedding vector contributes to our task. The models compute the embedding of the entire source code. The former has an embedding size of 1536, while the latter has a size of 1024.

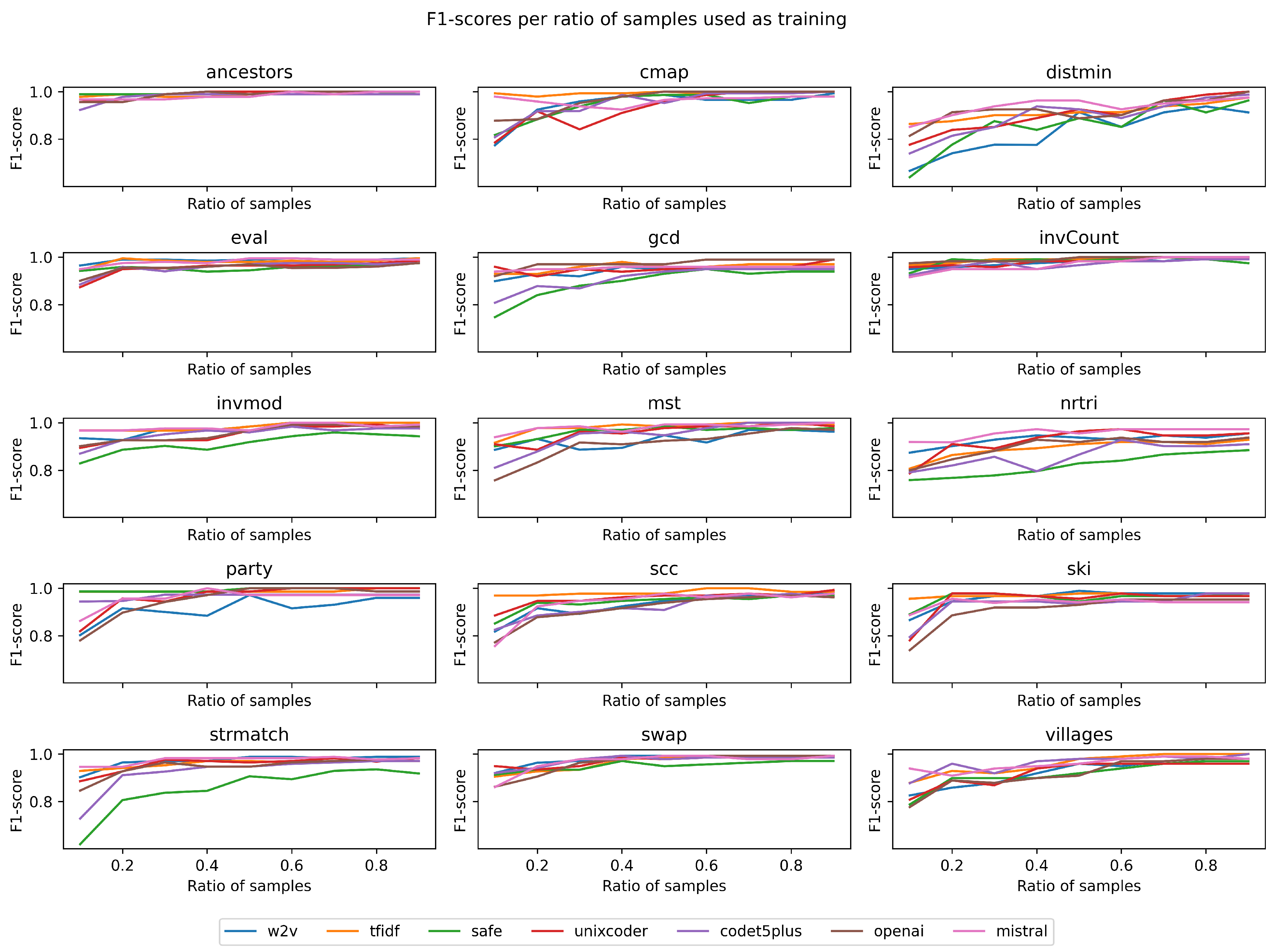

To determine how informative each embedding method is, we split the samples into a training set (90%) and a test set (10%) for each problem. For each problem, we plot the F1 score we would obtain if we used only x% of the training set to train an XGBoost model to predict the correct algorithmic solution. From the plots in

Figure 1, we observe that in many problems, even with as little as 20% of the data, we can train a model with over 90% accuracy. Our algorithm tries to find, in an unsupervised way, the most relevant subset of samples that can be used to infer the other samples.

Building clusters for a known value of K. To determine the clusters for each algorithmic solution, we have used three flavors of unsupervised learning.

Clustering with a single view. We refer to this method as hard clustering, which is the most straightforward approach. We run a specific clustering algorithm for each embedding technique, partitioning the source code into K clusters.

Clustering with multiview. We consider the number of distinct available embedding methods as distinct views of the same source code. This approach enables the use of the

MVSC (Multiview Spectral Clustering) algorithm [

22], which also determines the

K clusters.

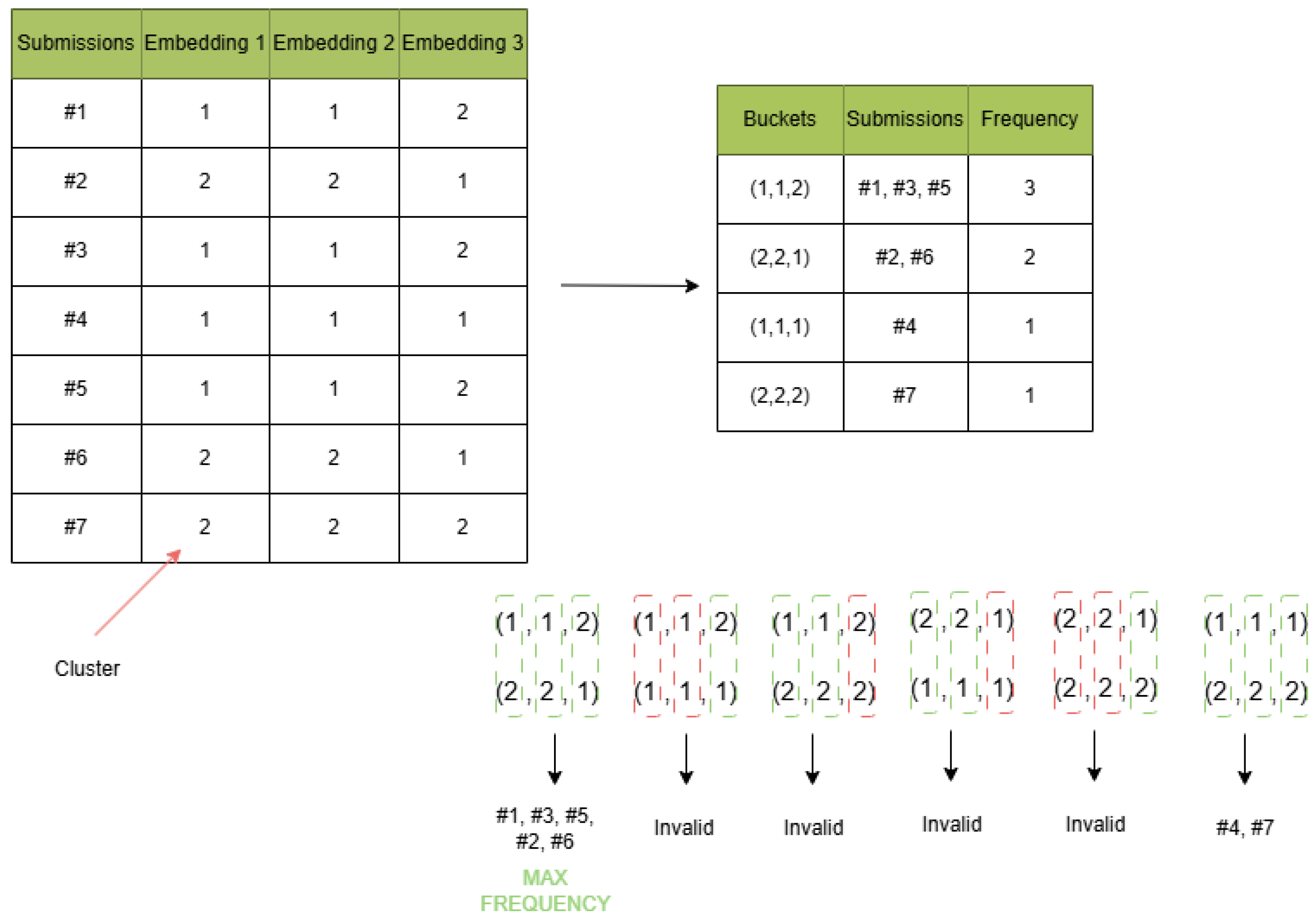

Clustering by voting. Assuming we have V views, where a view represents an embedding method, and for each view, one clustering algorithm will partition the embeddings into K groups. Thus, for each solution, we associate a vector of dimension V, where at each position i the value of is in the range [0, K − 1] and represents the cluster to which the solution belongs in the i-th view.

Let S(p) be the set of all solutions associated with a problem p where , , is the set of all indices for the clusters in a K clustering then . We denote as a mapping between a specific solution in a problem p to a V-dimensional vector. Each component of this vector corresponds to a specific view and contains the index of the cluster that contains the solution in that view. We observe that the same vector may represent several source-code solutions. Thus, we define the frequency of a vector as the number of source-code solutions represented by the same vector.

With this function defined, we find vectors that have no common coordinates and whose sum of frequencies is maximal. Furthermore, if we cannot find many vectors equal to

K (i.e., a known number of clusters), we must choose fewer clusters. We define

where

The task is to determine

A such that

has maximum value. The algorithmic solution is represented by the

vectors. These vectors represent the

K distinct algorithmic solutions we extract from each view. Thus, each algorithmic solution contains similar source-code solutions. The main idea can be visualized in

Figure 2.

Compared with the conference paper, which used a brute-force algorithm feasible for

and

, we improved it by adding various heuristics. We add each vector into a trie data structure [

23] and store its frequency at the corresponding leaf. If one can find

K distinct paths in the trie, then it means that on the first level, all clusters will be part of some path. In other words, the trie can be split into

K disjoint tries, from which we can select just a path from each trie without having a common cluster on the same level. We need to explore all possible paths and determine which ones yield a maximal sum. To search faster, whenever we choose some paths in a previous trie

i, we are not allowed to explore other paths that have a common prefix, since that would mean that we would be repeating some clusters. The pseudocode for the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1, and a figure showing some iterations can be found in

Appendix A.

| Algorithm 1 Maximum sum subset |

Require: All solution vectors to be added in in trie

- 1:

found_paths = Ø - 2:

best_paths = Ø - 3:

used_clusters = Ø - 4:

best_score = 0 - 5:

current_score = 0

- 6:

procedure Maximum_Sum_Subset(trie_root, node, level)(:) - 7:

if node is a leaf then - 8:

# add a new empty set in found_paths - 9:

current_score = current_score + node.frequency - 10:

if len(found_paths) == K then - 11:

if current_score > best_score then - 12:

best_score = current_score - 13:

best_paths = found_paths - 14:

end if - 15:

else - 16:

Maximum_Sum_Subset(trie_root, trie_root.child[len(found_paths) + 1], 0) - 17:

end if - 18:

current_score = current_score − node.frequency - 19:

# remove the last added set from found_paths - 20:

end if - 21:

for child of node do - 22:

if then - 23:

# add cluster in last added set in found_paths - 24:

used_clusters = used_clusters ∪ {(level, child.cluster)} - 25:

Maximum_Sum_Subset(trie_root, child, level + 1) - 26:

used_clusters = used_clusters∖{(level, child.cluster)} - 27:

# remove cluster in last added set in found_paths - 28:

end if - 29:

end for - 30:

end procedure

|

The algorithm can be interpreted as follows: each view represents a voter that partitions the items (i.e., the source code solutions) into k clusters. Each voter has its own parameters regarding the embedding used, the clustering algorithm, and the classification algorithm. The ideal situation occurs when voters perfectly agree on the distribution of items into clusters. The task is to correctly associate the clusters predicted by voter A with the clusters predicted by voter B. The problem becomes more complicated as the number of voters increases, making it harder to determine the match. The task is to determine the matching with the maximum number of identical items in coupled clusters.

After we determine the matching, we build a training dataset in which we assume the 1-st coordinate (i.e., the cluster

id to which the item belongs) is the truth label. Since the training dataset contains only a subset of the data, we employ co-training (a classifier per view) along with self-learning to predict the labels of the remaining solutions. In the main loop, we predict the label (i.e., the cluster

id) of the remaining items and consider that a label is correct if all classifiers predict it. These items are appended to the training dataset, and we retrain the voters only if the number of appended items exceeds a threshold

and we still have unlabeled items. Finally, the items that could not be labeled are discarded. Pseudocode for this algorithm is shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Unsupervised voting algorithm |

Require: Solutions-Dataset = solutions for a problem

- 1:

# Setup voters with their parameters: embedding, clustering algorithm, and classification algorithm - 2:

# Build Ground-Truth-Dataset which maximizes - 3:

Sols-Train = Ground-Truth-Dataset - 4:

Sols-Unlabeled = Solutions not in Sols-Train - 5:

while (# of valid solutions greater than and # Sols-Unlabeled greater than 0) do - 6:

= Train classifier on Sols-Train based on the i-th view - 7:

for all (Sols-Unlabeled) do - 8:

#Predict the label of solution by all voters - 9:

if (solution has same label in all voters) then - 10:

Append solution to Sols-Train - 11:

Remove solution from Sols-Unlabeled - 12:

end if - 13:

end for - 14:

end while - 15:

Sols-Test = Sols-Train - 16:

#Validate Sols-Test

|

Determine the optimal number K using clustering-by-voting. Since applying the unsupervised algorithm seems to yield a better result when

K is known, we also investigated if it could help in determining the optimal number

K. One method usually used in determining the optimal number

K is the Silhouette method [

24] (or other methods/indexes such as Elbow Method, Davies–Bouldin Index [

25], Calinski–Harabasz [

26] Index, Dunn Index [

26] or NbClust [

27]), which yields a score

. One could determine the optimal

K by testing with different Ks and choosing the one that gives the maximum score. The unsupervised method creates a subset

S from the initial dataset

D that maximizes the frequency sum, subject to

. Basically, the method introduces an additional feature

l in addition to

s, where

. We observed that the unsupervised method negatively affects the estimation of the optimal number

K. Let us assume we have a number of views

V and a select number of clusters

K. If we apply a clustering method on a specific view

, we can compute the Silhouette score for it. The total Silhouette score would be the average of the Silhouette scores for each view. The only difference between using and not using the unsupervised method is the step in which we choose to calculate the Silhouette score. In other words, if we apply the Silhouette score on the whole dataset or on the subset obtained. There are two scenarios to consider. (1)

. In this case, basically, the unsupervised method selects a subset equal to the original dataset so that the Silhouette method will return the same score. (2)

. In this case, we obtain a subset that is not equal to the original dataset. The unsupervised method removes entries from the dataset for which the embeddings from each view disagree. The problem is that even though this method helps find distinct algorithmic solutions when you know the number

K by removing non-obvious examples, it can also lead to the creation of additional clusters that are not distinct algorithmic solutions. For example, the additional clusters created may be related to how similar the actual text is.

4. Results

We evaluate each method by considering the optimal number of clusters for each problem. We denote the set of embeddings by {Word2Vec, Tf-Idf, SAFE, UniXcoder, CodeT5+, OpenAI, MistralAI}, the set of clustering algorithms by {Kmeans, Spectral Clustering, Agglomerative Clustering}, and the set of classification algorithms by {Xgboost}. We chose to use a single classification algorithm because using more would have increased the search space too much.

We define as the set of all subsets of dimension n with and . We mention that baseline results are obtained without hyperparameter tuning in either clustering or classification algorithms. In general, the evaluation of a clustering algorithm considers all label permutations, and the one with the highest F1 score is selected as the winner. Since problems may have algorithmic solutions with an imbalanced number of source-code solutions, the chosen quality metric is F1-macro because we want to treat each class equally.

The evaluation of the method of building clusters with a single view takes into consideration all the combinations obtained by the Cartesian product and evaluates each combination by the approach previously presented. Similarly, the method that employs multiview spectral clustering will use embeddings , , . The clustering-by-voting method is validated by determining the best results after co-training with classifiers and by obtaining the best results after classification. These approaches will use the Cartesian products as their setup , and , respectively.

4.1. Dataset

The dataset AlgoSol-15 [

1] is publicly available and consists of 15 problems whose descriptions are shortly presented below. The URLs of the problems, the number of solving strategies, and the number of solutions for each problem are presented in

Table 1.

ancestors—Given a tree (as a vector of parents) and a set of queries that want to determine the k-th ancestor for a given node x. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Dynamic Programming and Offline Queries, with 226 and 234 solutions.

cmap—It is a classical problem for determining the closest pair of points in a plane. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Distance Search and Divide et Impera, with 325 and 415 solutions, respectively.

distMin—It is a classical problem of finding a single-source shortest path in a weighted and directed graph. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Bellman-Ford and Dijkstra, each with 201 solutions.

eval—It is a classical problem for evaluating an expression that is provided as a string of characters that contains operands, parentheses, and basic operators (i.e., +, −, ×, /). The problem has three algorithmic solutions: Binary tree, Recursive function, and Iterative with stack, with 276, 374, and 312 solutions, respectively.

gcd—It is a classical problem for determining the greatest common divisor of two numbers. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Euclid by division and Euclid by subtraction, with 278 and 225 solutions, respectively.

invCount—It is a classical problem for counting inversions (i.e., (i, j) pairs where and in a given vector of numbers. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Binary Indexed Tree and Merge Sort, with 297 and 296 solutions.

invMod—It is a classical problem for determining the multiplicative inverse of a number modulo P, where P is a prime number. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Euler Totient and Extended Euclid, with 294 and 321 solutions, respectively.

mst—It is a classical problem for determining the minimum cost spanning tree for an undirected graph. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Kruskal and Prim, with 348 and 308 solutions, respectively.

nrTri—Given a vector of positive integer numbers, determine the number of non-degenerate triangles that can be formed such that all edges have distinct values. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Binary Search and Brute Force, with 322 and 240 solutions.

party—It is a classical 2-SAT problem for determining whether a set of constraints on Boolean variables can be satisfied or not. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: using Implication Reduction and Random variables with 341 and 118 solutions, respectively.

scc—It is a classical problem for determining the strongly connected components in a directed graph. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Kosaraju and Tarjan, with 351 and 308 solutions.

ski—It is given a set of n players a rank of i-th player taken into consideration only the first i − 1 players. The problem has three algorithmic solutions: Binary Indexed Tree, Segment Tree, and Treap with 142, 157, and 96 solutions, respectively.

strMatch—This is a classical substring search problem in which a pattern of length m is searched in a text of length n. The problem has three algorithmic solutions: Rabin-Karp, KMP, and Z-Algorithm, with 246, 347, and 230 solutions, respectively.

swap—Given two strings of characters s and t, determine the minimum number of swap operations such that s becomes equal to t. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Binary Indexed Tree and Merge sort, with 368 and 320 solutions, respectively.

villages—Given a list of villages in order, you have to determine the distance between two villages X and Y. There is a unique path between them. The problem has two algorithmic solutions: Breadth-First-Search (BFS) and Depth-First-Search (DFS), with 258 and 237 solutions, respectively.

For evaluating the performance of the proposed algorithms with the employed code embeddings, it is compulsory to have the ground truth. Considering that there is no labeled dataset for distinct solutions for competitive programming, we decided to label several problems manually. The AlgoSol-15 dataset consists of 15 problems from Infoarena, and the criteria for selection are: (1) the problem must have at least two distinct algorithmic solutions; (2) the number of source-code solutions for each class (i.e., algorithmic solution) should be large enough; (3) the classes should be as balanced as possible; (4) the algorithmic solutions to be as distinct as possible such that we may better evaluate how embeddings describe the algorithmic solutions for various implementations. The F1 score metric is used as an evaluation metric, which combines precision and recall.

4.2. Main Results

The main results are shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3. At the general level, it can be seen that, in most cases, the score is excellent across all problems, except for two. One reason for this discrepancy is that, in some cases, the code is very similar across distinct solutions, and the embeddings cannot discriminate between them. For example, in the case of

villages, both Breadth-First Search and Depth-First Search are valid distinct solutions, but the code is pretty similar. The method which have the highest overall score is Unsupervised Voting, followed by Hard Clustering and MultiView Spectral Clustering.

In the case of Hard Clustering, we observe that at the embedding level, Mistral and UniXcoder seem to encapsulate the most relevant information for discriminating between distinct solutions, while K-means and Agglomerative Clustering achieve the best results. Overall, the scores are over 0.9, except for the two problems that seem to have lower results in general. There is also a problem, gcd, where Hard Clustering has a very different score compared with the other methods. This suggests that embeddings other than W2V contribute negatively to the problem.

MultiView Spectral Clustering, on the other hand, seems to improve scores on some problems (e.g., cmap, nrtri) while degrading the score on others (e.g., gcd, mst). The reason for this may be that MVSC uses all samples with multiple views, which could introduce additional noise, as not all embeddings improve performance. Another limitation is that MVSC uses only Spectral Clustering as a clustering method, whereas others can use K-means or Agglomerative Clustering as well.

The proposed voting algorithm is an ensemble method that combines predictions from multiple classifiers to improve the classifier’s overall performance. The scores seem to improve because the algorithm is allowed to focus on a subset of data, using a more robust dataset as a starting point with less noise. In 14 problems, the score is higher than in the other two methods (consider both results with and without co-training), but the algorithm also behaves poorly in finding distinct solutions in the gcd problem. This suggests that just the W2V Embeddings capture the relevant information, and in this case, the multiview approach has a negative impact. One limitation of the algorithm, compared with the other two methods, is that it does not predict all the samples. Because the algorithm has this limitation, there may be cases where the score is perfect but the subset is tiny. This indicates that UV has found a small cluster of solutions that are easy to predict (it may also find just a single cluster). In our evaluation, we selected the best scores that have the predicted label distribution as close as possible to that of the original dataset.

4.3. Computational Cost

The number of solutions influences the computational cost N, views V and clusters K, as well as the clustering and embedding methods used. The computational cost can be described in terms of the following components:

Computational cost of embeddings—An embedding method has a time complexity function, , dependent on the number of samples N and a number of tokens l. Note that each embedding represents a solution as a vector with a dimensionality of . The total time complexity is influenced by the number of views V and it becomes .

Computational cost of clusterings—A clustering method has a time complexity function, , dependent on the number of samples N, clusters K and embedding dimensionality . The total time complexity is influenced by the number of views V and it becomes .

Computational cost of clustering by voting—MAP—In the worst case scenario, the cost matrix associated with MAP has a size of

and

feasible solutions [

29]. Although the number of feasible solutions is really big, there are some practical aspects that drastically reduce the number of feasible solutions. In competitive programming, the number

K tends to be very small (∼3). Moreover, the cost matrix tends to be sparse due to the number of limited valid submissions

N for a problem, thus making a heuristic approach suitable for this scenario. In this paper, for example, the maximum number of distinct algorithmic solutions

, the number of views

and the number of solutions per problem

.

Computational cost of clustering—co-training—Given a model m, the time complexity to train on the subset S obtained from the MAP phase is for each view i, which is dependent on the size of the subset and the dimensionality of the embedding. Since, in our case, co-training follows a self-training procedure, the voting between different views is repeated as long as we add more than the threshold () solutions to the training set S. In the worst-case scenario, the complexity becomes .

The entire evaluation takes about 1 h for all the solutions to a problem, assuming that preprocessing and embedding computation steps have been performed beforehand. The experiments were performed on a system with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-14900KF CPU, Nvidia GTX 1070 8 GB GPU and 64 GB RAM. Note that the GPU is used only for embedding computation, and the proposed method is mostly CPU-bound.

4.4. Scalability and Variance Across Runs

In terms of scalability, the proposed method is highly scalable. Considering that the algorithm works on a single problem p, the algorithm can be scaled by employing it in parallel on multiple problems . In terms of variability across runs, Unsupervised Voting depends on the variability of the clustering algorithms and the model used in co-training. The MAP algorithm is deterministic and depends on the clustering obtained in each view. This implies that if one of the clustering methods has a decrease in quality on a specific embedding in a view, then the quality of Unsupervised Voting will be affected as well.

4.5. Limitations

Even though the UV performs better than the baseline clustering methods, there are some limitations: (1) The increased computation cost associated with MAP could make the algorithm infeasible in scenarios where the number of clusters K and views V is large. In practice, especially in education, the number of different approaches one could take to solve a problem tends to be low. (2) The algorithm assumes that K is known, which can be a limiting factor in practical scenarios where K is usually unknown. In our situation, from a practical point of view, since K tends to be small, one could rerun the algorithm for various values of K and sample some solutions from each cluster. (3) The number of problems presented in AlgoSol-15 is small and may not be enough to capture scenarios in which UV performs worse than the other methods. Extending the dataset by manually annotating additional problems is not feasible due to its labour-intensive nature, and an automatic approach is needed.

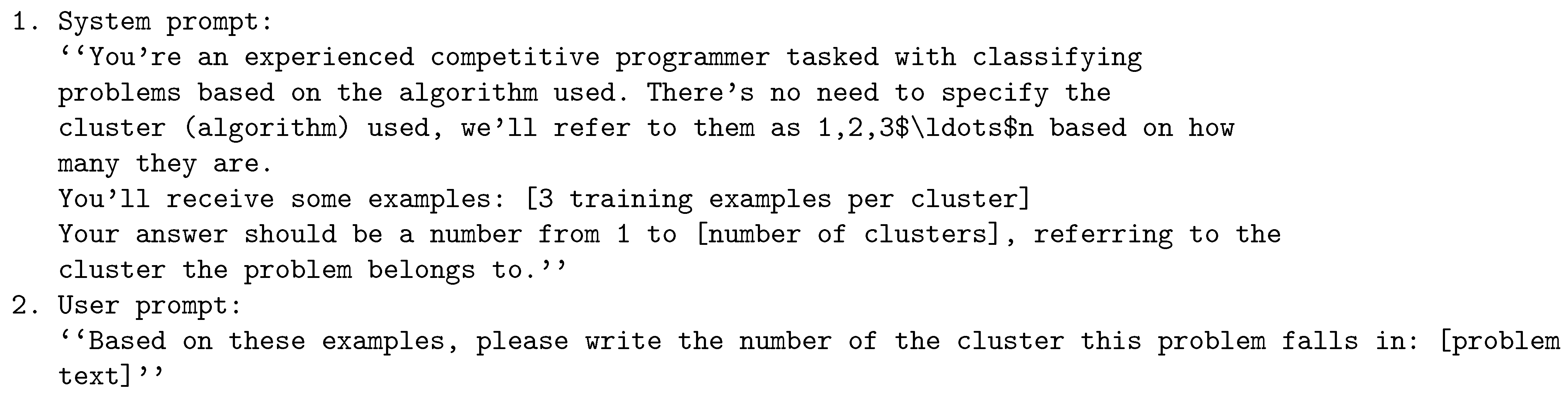

5. Comparison Against ChatGPT

We evaluated our unsupervised voting approach against two of ChatGPT’s latest models: GPT-4o and GPT-4.1. For both evaluations, we used the same methodology: we created an initial prompt

Figure 3 describing the algorithm clustering task and provided 3 examples per cluster as training data for each problem. The results can be found in

Table 4.

The results demonstrate that GPT-4.1 significantly outperforms GPT-4o across almost all problems, with notable improvements in problems like villages, party and eval.

GPT-4.1 achieves F1 scores ranging from 0.73 to 0.96 across the test problems, generally outperforming GPT-4o but still falling short of our voting approach in most cases. The performance gap is particularly evident in problems like distmin (voting: 0.981 vs. GPT-4.1: 0.76) and swap (voting: 0.967 vs. GPT-4.1: 0.73), where our method better captures the nuanced implementation variations.

Interestingly, GPT-4.1 outperforms our voting approach on the villages problem (0.93 vs. 0.852), which involves distinguishing between DFS and BFS implementations. This suggests GPT-4.1’s reasoning capabilities may better identify structural patterns in these algorithmically similar graph traversal approaches than our method.

The gcd problem is another notable case in which GPT-4.1 (0.88) outperforms our voting approach (0.669). This aligns with our observations of the algorithm’s highly structured and mathematical nature. With limited implementation variations and a simple structure, GPT models can effectively recognise the patterns without requiring the complex embedding combinations our voting approach uses.

For algorithms with near-perfect clustering in our voting approach, like ancestors, invCount, and party, GPT-4.1 achieves respectable but still lower scores (0.92, 0.96, and 0.96, respectively), demonstrating the voting approach’s superior ability to handle diverse implementation patterns in most scenarios.

6. Conclusions

The paper presents a dataset consisting of source codes for 15 algorithmic problems. The source code was represented using seven embedding methods to perform a data analysis aimed at determining the number of distinct algorithmic strategies and, possibly, labelling a source code as belonging to a specific algorithmic strategy. The data analysis had four methods: hard clustering, multi-view spectral clustering, and voting with and without co-training. The hard-clustering approach achieved the highest score in 3 problems. The multi-view spectral clustering showed marginal improvement on some problems, but the overall scores were similar to those from the reference hard clustering.

Except for one problem (i.e., gcd), which seems to have only just an embedding with such a high score in hard clustering, unsupervised voting obtained the largest score for all problems. Thus, the voting approach may solve the problem only if enough (embedding, clustering algorithm) pairs have reasonably good results. The worst-case scenario is when all voters perform poorly, or when only one performs well. This is the main limitation of the proposed approach, as the quality of clustering and code embedding represents an inherent characteristic that will propagate into the voting method.

Therefore, we have found that the voting strategy proved effective since we used seven embedding methods and three clustering methods in an unsupervised data analysis pipeline.

Preliminary experiments were conducted to determine whether ChatGPT performs well on the task at hand using a small dataset. We observed that for solutions with the same function name as the algorithm used, ChatGPT made the proper connection, but not in all cases. For a solution that uses the classical Depth First Search (DFS) graph algorithm, changing the function name causes ChatGPT to fail to identify the algorithm. This has been observed when the algorithm’s name has been replaced with a similar one. On the other hand, when the name of the algorithm was replaced with a random one or has been obfuscated (e.g., by naming the function solve() as it frequently appears in competitive programming), ChatGPT manages to identify the purpose of the algorithm (e.g., graph traversal, substring search, etc.) but does not necessarily detect the correct algorithm that has been used as implementation.

Further work may scale up to processing a dataset with many more problems, although there are not too many publicly available datasets at the moment of writing this paper. Besides this, for the task of determining the optimal number K using clustering by voting, we have identified that the Unsupervised Voting has a negative impact by facilitating the creation of well-defined clusters. These well-defined clusters can falsely show a strong indication of K being correct in methods like Silhouette method. As future work, we would like to delve deeper into this phenomenon and find ways to mitigate it.