Abstract

This paper introduces a novel observer-based, fully distributed fault-tolerant consensus control algorithm for model-free adaptive control, specifically designed to tackle the consensus problem in nonlinear multi-agent systems. The method addresses the issue of followers lacking direct access to the leader’s state by employing a distributed observer that estimates the leader’s state using only local information from the agents. This transforms the consensus control challenge into multiple independent tracking tasks, where each agent can independently follow the leader’s trajectory. Additionally, an extended state observer based on a data-driven model is utilized to estimate unknown actuator faults, with a particular focus on brake faults. Integrated into the model-free adaptive control framework, this observer enables real-time fault detection and compensation. The proposed algorithm is supported by rigorous theoretical analysis, which ensures the boundedness of both the observer and tracking errors. Simulation results further validate the algorithm’s effectiveness, demonstrating its robustness and practical viability in real-time fault-tolerant control applications.

Keywords:

MFAC; nonlinear MASs; consensus control; fault-tolerant control; observer-based control; data-driven control MSC:

93D25

1. Introduction

In recent years, multi-agent systems (MASs) have received significant attention due to their wide-ranging applications in autonomous driving [1,2], unmanned aerial vehicles [3,4], and sensor networks [5,6]. Among various coordination objectives, consensus control plays a central role by enabling agents to reach agreement on key variables through local communication, supporting higher-level tasks such as formation control [7], distributed estimation [8], and cooperative decision-making [9]. To achieve consensus, existing methods are broadly classified into model-based and model-free approaches. While model-based strategies rely on known system dynamics and offer rigorous theoretical guarantees, their applicability is often limited in practical scenarios involving heterogeneous agents, uncertain environments, or time-varying dynamics, where accurate modeling is difficult or infeasible. These limitations have led to growing interest in model-free or data-driven consensus control methods, which utilize real-time input–output data to achieve coordination without requiring explicit knowledge of system models.

Among model-free control frameworks, model-free adaptive control (MFAC) has shown particular effectiveness due to its reliance on online input–output data and pseudo-gradient estimation, which avoids explicit model identification while ensuring low complexity and interpretability [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Other data-driven approaches, such as reinforcement learning [16,17], neural networks [18], and fuzzy-based control [19], have also been explored, yet they often require extensive training or large datasets, limiting their real-time applicability. In contrast, MFAC achieves faster convergence with lower computational cost, making it particularly well-suited for real-time control of uncertain nonlinear systems. Recently, MFAC has been extended to the multi-agent domain [20,21,22,23,24], where distributed MFAC-based controllers have been proposed to solve consensus problems under model uncertainty using only local data. In [20], a MFAC framework was developed to address the consensus control problem of multi-agent systems (MASs) subject to deception attacks. The asymmetric bipartite consensus tracking problem was studied in [22], where event-triggered mechanisms were incorporated to improve communication efficiency. In addition, ref. [23] investigated distributed control under denial-of-service (DoS) attacks and external disturbances. While these schemes have shown promising performance, they also introduce several intrinsic challenges. Notably, many existing designs rely on consensus error signals, which often involve future outputs or states of neighboring agents—quantities that are not directly measurable in real time. This dependence increases implementation complexity and can introduce estimation errors. In addition, the use of consensus errors typically leads to parameter coupling among agents, thereby complicating controller tuning and reducing scalability in large or heterogeneous networks.

A further limitation of existing MFAC-based consensus methods is the assumption of nominal actuator functionality. In practice, actuator faults—such as bias, partial loss of effectiveness, or complete degradation—frequently occur due to hardware aging, mechanical wear, or harsh environmental conditions. These faults can significantly distort the applied control signal, degrade tracking performance, or even prevent consensus. As far as we known, only a relatively small number of mfac-based multi-intelligent body consistency studies have considered errors that occur on systems [25,26,27]. In [25,26], the output saturation problem was addressed in the tracking control of multi-agent systems (MASs). Actuator faults were further investigated in [27], where a distributed control strategy was developed to ensure system stability under fault conditions. Moreover, since many existing MFAC consensus schemes rely on consensus error terms, a fault in one agent not only affects its own behavior but also propagates through the network via local interactions. This inter-agent coupling can amplify fault effects and deteriorate global control performance, particularly in large-scale or tightly interconnected systems. These challenges underscore the importance of developing robust, fault-tolerant consensus strategies for multi-agent systems under model uncertainty.

Motivated by the above challenges, this paper develops a fully distributed fault-tolerant consensus control framework for nonlinear multi-agent systems is paper, without assuming prior knowledge of agent models. The proposed approach integrates MFAC with real-time observation and compensation mechanisms. The main contributions of the paper are as follows:

- A fully distributed and purely data-driven consensus control framework is proposed for nonlinear multi-agent systems subject to actuator faults and unknown dynamics. The framework is implemented using only local real-time input–output data and neighbor communication, without relying on global information, system models, or offline training. This design ensures high scalability, adaptability, and applicability in large-scale, uncertain, and fault-prone environments, while significantly reducing implementation complexity.A distributed data-driven observer is designed to eliminate structural coupling and support independent reference tracking for each agent. Unlike traditional MFAC-based algorithms [20,21,22,23,24], where controller design relies on system-wide consensus errors, the introduction of a distributed data-driven observer removes this dependency. Each agent estimates the leader’s state using only local and neighboring input–output data, allowing independent reference tracking and controller tuning. This structure mitigates the propagation of local faults and enhances the overall robustness of the distributed control system.

- An extended state observer (ESO) is integrated into the control framework to enable real-time fault estimation and compensation. The ESO reconstructs unknown actuator faults and external disturbances from local input–output measurements and feeds the estimates into the control loop for adaptive correction. This mechanism significantly improves consensus reliability under input degradation, without relying on centralized diagnosis, prior model knowledge, or additional sensing infrastructure.

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

2.1. Graph Theory

A weighted graph is utilized to characterize the interaction topology among the agents, where denotes the set of nodes, represents the edge set, and is the associated adjacency matrix. An edge implies , indicating that agent j can receive information from agent i; otherwise, . The neighbor set of agent i is defined as . A directed path from node i to node k exists if a sequence of edges connects them, such as . A directed graph possesses a spanning tree if there exists at least one node (root) that has a directed path to every other node in the graph. The diagonal matrix captures the influence of the leader on each follower, where if follower i can access the leader’s information; otherwise, .

Assumption 1

([28]). A spanning tree is assumed to exist in the graph , and the leader is accessible from at least one root node via a directed connection.

2.2. Problem Formulation

Consider a fully heterogeneous nonlinear MAS composed of followers and a single leader. The dynamics of the ith follower subject to actuator faults are described by:

where denotes the output of the ith follower. and are the input, and actuator fault of the ith follower, and represents the unknown dynamics.

The leader’s dynamics is described by:

where and denote the leader’s state and the output, respectively. and denote the internal dynamics and output dynamics of the leader, respectively.

Assumption 2

([29]). The modulus of every eigenvalue of is less than or equal to one.

3. Observer-Based Data-Driven Fault-Tolerant Control Algorithm Design

3.1. Data-Driven Distributed State Observer

To effectively mitigate the adverse effects of actuator faults in MASs, it would be ideal for each follower agent to directly access the state information of the leader. However, in practical scenarios, such direct communication is often constrained by limitations in network topology, communication bandwidth, or system security requirements. These constraints make it infeasible for all agents to receive global information or maintain continuous access to the leader’s state. Therefore, it becomes essential to design distributed observer mechanisms that rely solely on local real-time information exchanged with neighboring agents. In this work, we propose three distributed observers that enable each agent to estimate the leader’s dynamics and state independently.

where , and denote the estimation of the internal dynamics, output dynamics and leader’s state, respectively. , , and are the parameters to be designed.

Lemma 1

([29]). Consider a fully heterogeneous nonlinear multi-agent system (MAS) with the leader’s dynamics given by (2). Assuming that Assumptions 1 and 2 hold, and each follower implements the distributed observer as defined in (3), the estimates of the system matrices, , , and state for each agent i, will converge asymptotically to the leader’s system matrices , , and state , respectively, as . This convergence holds provided that the observer gains satisfy the following conditions:

where represents the spectral radius of the matrix associated with the graph topology.

Remark 1.

The introduction of the distributed observer decouples the overall multi-agent system, eliminating the reliance on consensus-error-based design inherent in traditional MFAC methods. This decoupling not only improves the scalability and flexibility of the control architecture but also prevents fault propagation among agents, thereby enhancing the overall robustness of the distributed control system.

3.2. Data-Driven Fault-Tolerant Control Algorithm

3.2.1. Data Model Construction

Assumption 3

([30,31]). The dynamics of the ith follower in the MAS is assumed to satisfy the following generalized Lipschitz condition.

where , , and is a constant.

Lemma 2

([32]). Given Assumption 3 and the condition , the dynamics of the ith follower subject to actuator faults can be equivalently expressed by the following data-based model.

where is the pseudo-partial-derivative (PPD), , , , .

3.2.2. Extended State Observer

Define . Combined with (4), we have

where and are the estimation of and , respectively. and are observer gains.

Remark 2.

The ESO is employed to estimate controller errors in real time, providing essential information for the subsequent controller design. Since the estimation is continuously updated, once the controller error vanishes, the ESO output converges to the true value. This property ensures the correctness of the controller design and contributes to maintaining system stability.

3.2.3. Data-Driven Fault-Tolerant Controller Design

Select the cost function of the ith follower as

where is the weighting parameter to limit the change in the input of the ith follower, .

Substituting (4) and (5) into (6), and then minimizing (6) with respect to , we can obtain

where is the estimation of ; and are step factors for flexibility.

Consider the cost function with respect to as

where is a positive weighting parameter.

Then, the estimation of PPD can be obtained by minimizing (8), so that

where is the step size.

Combining (7) and (9), the model-free adaptive security controller for the ith follower is shown as

where is the initial value of ; is a positive constant.

Remark 3.

In the proposed control algorithm, several parameters, , , , , and , must be properly tuned to ensure satisfactory performance. The regularization factor determines the trade-off between control responsiveness and input smoothness: smaller values enhance response speed but may compromise stability, whereas larger values improve robustness. The parameters and jointly influence the PPD estimation dynamics, balancing estimation accuracy, smoothness, and adaptability. A smaller or larger accelerates adaptation but increases sensitivity to disturbances. The step sizes and regulate the tracking and fault-compensation processes, where higher strengthens tracking performance and moderates the balance between fault rejection and stability. Finally, and govern the update rate of the fault estimator, and appropriate tuning of these parameters ensures reliable and stable fault detection.

4. Stability Analysis

Theorem 1.

Consider the MASs with actuator faults as (1), let Assumption 1 hold and design the controller as (10), the tracking error of the MASs will be bounded if the following inequalities are satisfied:

Proof of Theorem 1.

This proof is divided into two parts, proving the boundedness of the estimation of PPD and the containment error, respectively.

Part 1: This part consists of two cases. In case 1, the function (10b) is satisfied, and it is obvious that the estimation of PPD is bounded.

In case 2, substituting (10a) into the estimation error yields:

Then, we can obtain

Also, it is easy to gain , and . Thus, we can obtain

where is a positive constant that can be obtained by selecting and to satisfy .

Based on the above analysis, since both and are bounded, it follows that is also bounded.

Part 2: In this part, we will give the proof of the boundedness of the tracking error . By Theorem 1, if remains bounded as , then is also bounded.

From function (10c), we have

where

Substituting (15) into (4), we can obtain

where and .

Then, we can obtain

where .

According to function (5), we have

Then, we can obtain

Substituting (17) into (19), we can obtain

Select the Lyapunov function as , where .

Then, the difference of can be obtained as

Substituting (17) and (20) into (21), we have

For the boundedness of , , and , it is possible to be obtain that , , and . Then we have

where , and .

From the (11), and are all positive constant. Based on the Lyapunov stability theory, we can obtain if at least one of the following inequalities holds . Therefore, and are bounded. □

Theorem 2.

For the ESO designed as (5), if and are selected to ensure , then the observer error of ESO is bounded.

Proof of Theorem 2.

From (5), we have

where and denote the observer errors of ESO. .

Due to is satisfied, the spectral radius of is less than 1.

Then, we have .

Combined with the boundedness of , we can obtain

where , and the observer errors are bounded. □

5. Simulation

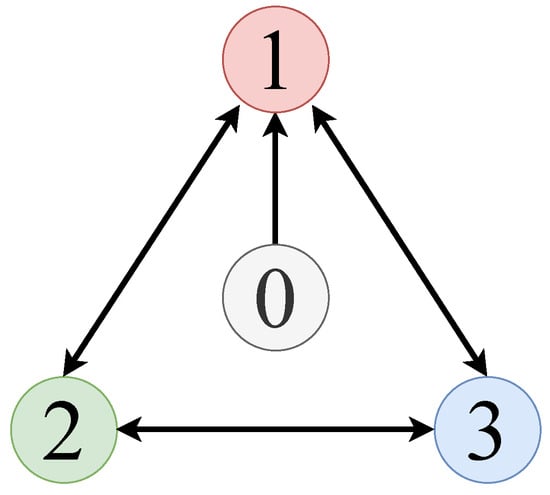

Consider a heterogeneous MAS with three followers and one leader, where the leader’s output is time-varying and non-convergent. The communication topology is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The communication topology of numerical simulation.

Define the dynamics of the leader as:

Define the dynamics of the followers as:

Moreover, assume the actuator faults occur on follower 1 as

The parameters of the distributed observers are selected as , and . The parameters of the ESO are set as and . The parameters of the adaptive controller are set as , , , , , , , , , , , . Moreover, the initial outputs of the followers are selected as and the initial state of the leader is set as . The initial PPDs of the followers are selected as , and .

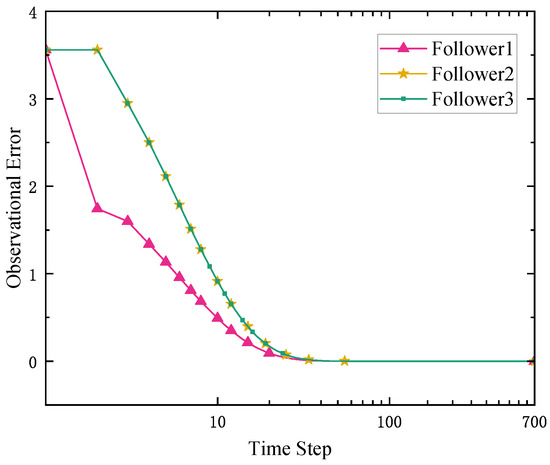

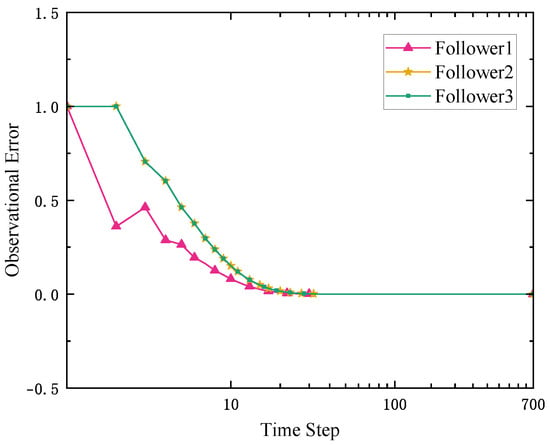

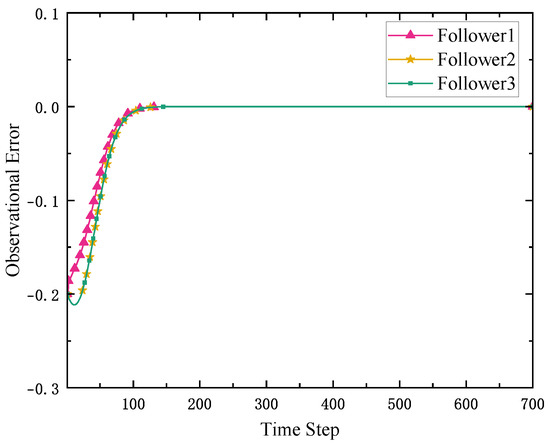

The performances of the proposed observer are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. As illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the followers can effectively observe the leader’s internal and output dynamics at the 50 time step. Moreover, the leader’s output can also be observed at the 200th time step. These results show that the MAS has been fully decoupled by the distributed observers, and the followers can obtain the leader’s output after the 200th step.

Figure 2.

The observational error of the internal dynamics of the leader.

Figure 3.

The observational error of the output dynamics of the leader.

Figure 4.

The observational error of the output of the leader.

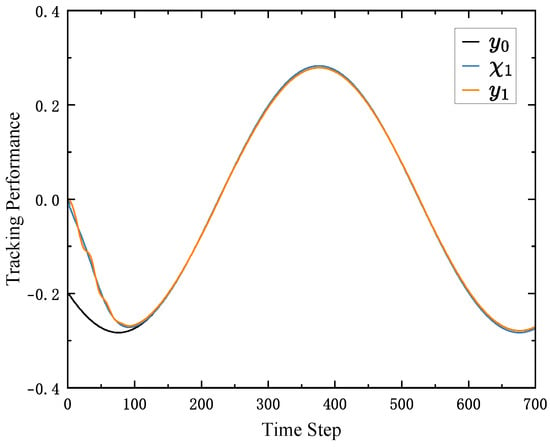

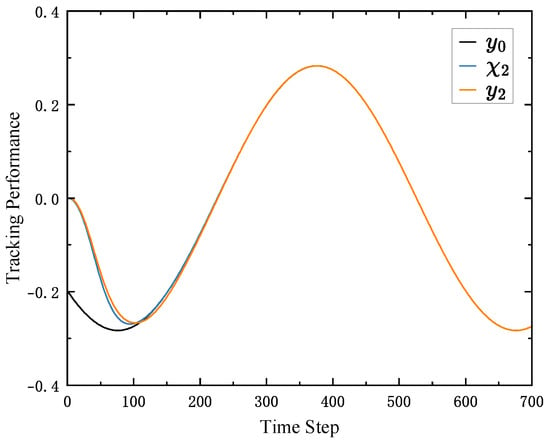

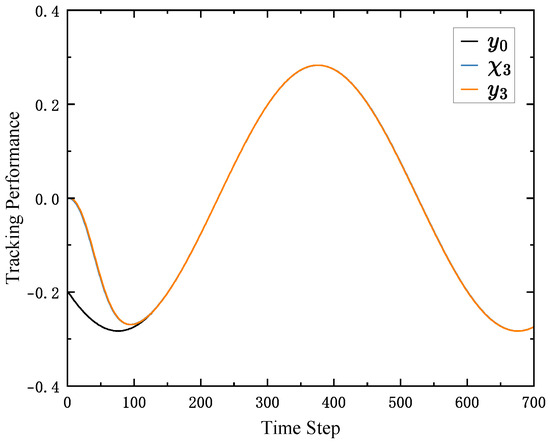

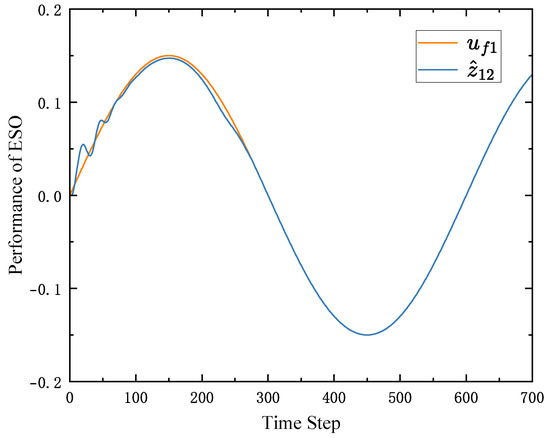

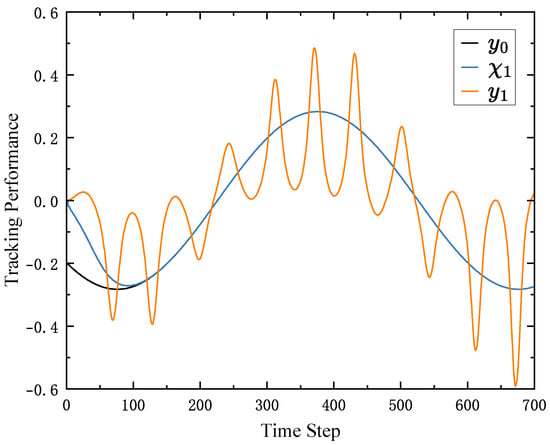

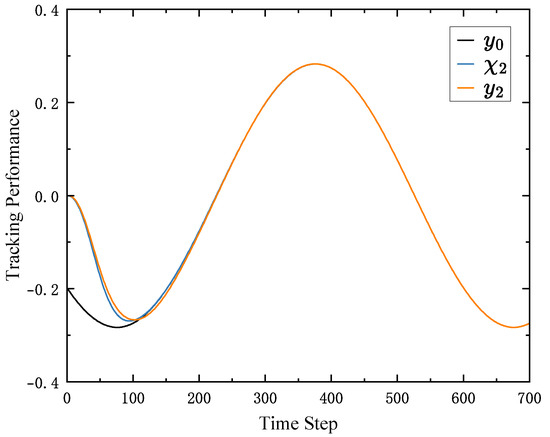

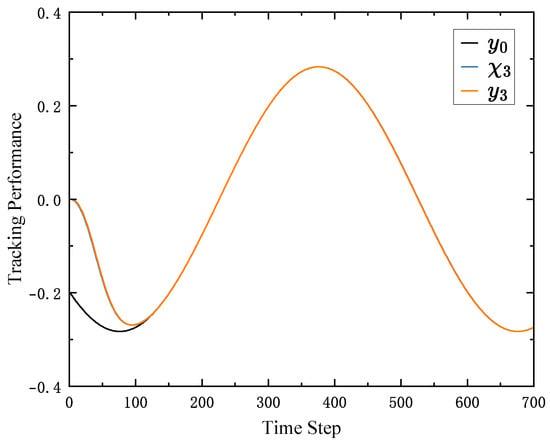

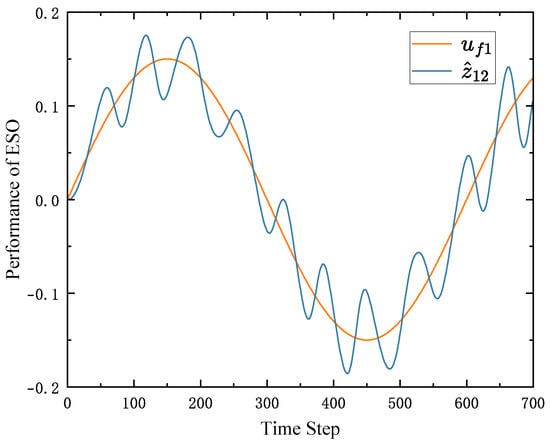

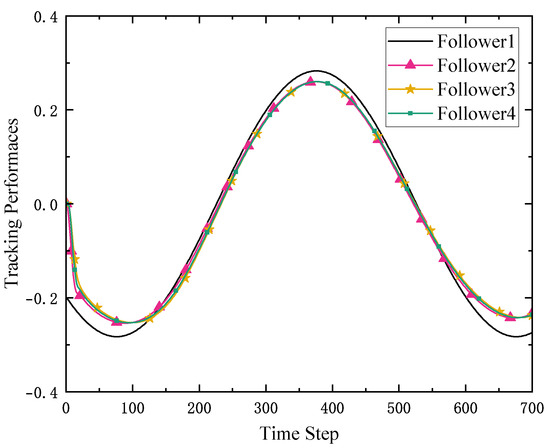

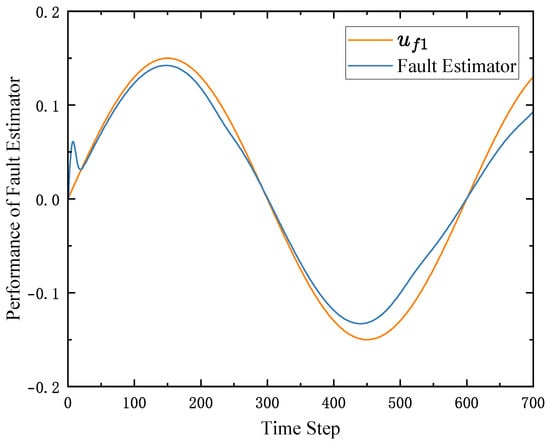

The tracking performances of the followers are shown in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively. From the results of the Figures, based on the distributed observer and ESO, the followers can track the trajectory of the leader after the 300th time step. Moreover, the performance of ESO is shown in Figure 8. From Figure 8, the ESO can estimate the increment of the actuator faults after 300th time step. These results show that the proposed algorithm can deal with the consensus control problem of MASs with unknown actuator faults.

Figure 5.

The tracking performance of follower 1.

Figure 6.

The tracking performance of follower 2.

Figure 7.

The tracking performance of follower 3.

Figure 8.

The performance of ESO.

To evaluate the decoupling capability of the proposed algorithm and its effectiveness in preventing error propagation across the system, the parameters of follower 1 were deliberately modified such that it fails to estimate the control error accurately and cannot track the leader’s trajectory. The tracking performance of all followers is illustrated in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, while the performance of the ESO is shown in Figure 12. A comparison between Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Figure 6 and Figure 7 indicates that the tracking performances of followers 2 and 3 remains unaffected, despite the degraded performance of follower 1. These results show that the proposed algorithm enables system decoupling through the use of observers. When the ESO of one agent fails, the others remain unaffected, demonstrating the scalability and robustness of the proposed control strategy.

Figure 9.

The tracking performance of follower 1 with unsuitable parameters.

Figure 10.

The tracking performance of follower 2.

Figure 11.

The tracking performance of follower 3.

Figure 12.

The performance of ESO.

The tracking performances of the followers under the algorithm in [27] are shown in Figure 13. As we can see in Figure 13, the followers cannot track the leader’s trajectory under the algorithm in [27]. As shown in Figure 14, the fault estimator designed in [27] cannot estimate the actuator faults well. These results show that under the algorithm design in [27], due to the coupling between multiple intelligences, actuator errors propagate through the system, thus affecting the stability of the whole system.

Figure 13.

The tracking performances of followers under the algorithm in [27].

Figure 14.

The performance of the fault estimator in [27].

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a novel observer-based, fully distributed fault-tolerant consensus control algorithm for MFAC is proposed to address the consensus control problem in nonlinear MASs. The proposed method overcomes the challenge of followers lacking direct access to the leader’s state by utilizing a distributed observer that estimates the leader’s state from local information. This approach decouples the consensus control problem into independent tracking tasks for each agent. An ESO based on a data-driven model is introduced to estimate unknown actuator faults, particularly brake faults, and an adaptive controller is designed for fault compensation. Theoretical analysis confirms the boundedness of observer and tracking errors. Finally, simulation results validate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in fault-tolerant control scenarios. Future work will focus on conducting physical experiments to further validate the proposed method and extending the framework to event-triggered mechanisms and partially connected network topologies.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.Z., Y.L. and M.Z.; Software, D.L. and J.C.; Validation, D.L., Y.L. and D.G.; Formal analysis, D.L., S.S. and M.Z.; Investigation, D.L. and Y.L.; Resources, Y.Z., D.L. and S.S.; Data curation, D.G., J.C. and S.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z.; Writing—review & editing, D.G.; Visualization, M.Z.; Supervision, S.S.; Funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62303095), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2682025CX080).

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, because the data are not publicly available due to specific confidentiality agreements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Omeiza, D.; Webb, H.; Jirotka, M.; Kunze, L. Explanations in autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 10142–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y. A survey of world models for autonomous driving. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.11260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghari, A.A.; Jumani, A.K.; Laghari, R.A.; Nawaz, H. Unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Liu, C.; Han, Q.L.; Song, J. Unmanned aerial vehicles: Control methods and future challenges. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Wazirali, R.; Abu-Ain, T. Machine learning for wireless sensor networks security: An overview of challenges and issues. Sensors 2022, 22, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Swetha, G.; Gupta, S.; Madhavi, K. Routing in wireless sensor networks using machine learning techniques: Challenges and opportunities. Measurement 2021, 178, 108974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, H.; Lewis, F.L.; Wang, X. Data-driven optimal formation control for quadrotor team with unknown dynamics. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 7889–7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, T. Distributed estimation for multi-subsystem with coupled constraints. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 1548–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgren, P.; Srivastava, V.; Leonard, N.E. Distributed cooperative decision making in multi-agent multi-armed bandits. Automatica 2021, 125, 109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, P.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X. High-precision magnetic field control of active magnetic compensation system based on MFAC-RBFNN. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 6006510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.F.; Su, M.Y.; Jin, X.Z.; Che, W.W. Event-triggered MFAC of nonlinear NCSs against sensor faults and DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 4409–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Ren, Q.; Ma, H.; Chen, G.; Li, H. Model-free adaptive control for nonlinear systems under dynamic sparse attacks and measurement disturbances. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 4731–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, M.L. A robust sliding-mode based data-driven model-free adaptive controller. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2021, 6, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Jin, S.; Bu, X.; Hou, Z.; Yin, C. Model-free adaptive control for a class of MIMO nonlinear cyberphysical systems under false data injection attacks. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2022, 10, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, J.; Yan, H.; Qi, W.; Cheng, J. Finite-time model-free adaptive control for discrete-time nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 4113–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Gao, F. Reinforcement learning-based optimal fault-tolerant tracking control of industrial processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 16014–16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, P. Model-free output feedback optimal tracking control for two-dimensional batch processes. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 143, 109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Zhao, H.; Song, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Sun, D. Adaptive control of manipulator based on neural network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 4077–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Z.; He, Y.; Luo, X. FCAN-MOPSO: An improved fuzzy-based graph clustering algorithm for complex networks with multiobjective particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 3470–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hou, Z. Distributed model-free adaptive control for MIMO nonlinear multiagent systems under deception attacks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 53, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, L.; Yi, X. Model-free adaptive control for nonlinear multi-agent systems with encoding-decoding mechanism. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Netw. 2022, 8, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Bu, X.; Cui, L.; Hou, Z. Event-triggered asymmetric bipartite consensus tracking for nonlinear multi-agent systems based on model-free adaptive control. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 10, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.Z.; Li, Y.X.; Hou, Z.S. Distributed model-free adaptive control for multi-agent systems with external disturbances and DoS attacks. Inf. Sci. 2022, 613, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.S.; Che, W.W.; Deng, C.; Wu, Z.G. Distributed model-free adaptive control for learning nonlinear MASs under DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Peng, L.; Yu, H. Model-free adaptive consensus tracking control for unknown nonlinear multi-agent systems with sensor saturation. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2021, 31, 6473–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hou, Z. Model-free adaptive containment control for unknown multi-input multi-output nonlinear MASs with output saturation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2023, 70, 2156–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Distributed model free adaptive fault-tolerant consensus tracking control for multiagent systems with actuator faults. Inf. Sci. 2024, 664, 120313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lewis, F.L.; Xie, K.; Lyu, Y.; Xie, S. Distributed output data-driven optimal robust synchronization of heterogeneous multi-agent systems. Automatica 2023, 153, 111030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. The Cooperative Output Regulation Problem of Discrete-Time Linear Multi-Agent Systems by the Adaptive Distributed Observer. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 1979–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J. Event-triggered model-free adaptive consensus tracking control for nonlinear multi-agent systems under switching topologies. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2022, 32, 8646–8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Guo, J.; Cui, L.; Hou, Z. Event-triggered model-free adaptive containment control for nonlinear multiagent systems under DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2023, 11, 1845–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hou, Z. Learning-based model-free adaptive control for nonlinear discrete-time networked control systems under hybrid cyber attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 54, 1560–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).