Short Video Marketing or Live Streaming Marketing: Choice of Marketing Strategies for Retailers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Research Questions and Major Findings

1.3. Contribution Statement and Structure of This Paper

2. Literature Review

2.1. Short Video Marketing

2.2. Live Streaming Marketing

2.3. Literature Review Summary

3. Model

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Strategy S

3.3. Strategy L

3.4. Strategy H

4. Strategy Comparison and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of the Impact of Different Strategies on the Retailer’s Pricing and Demand

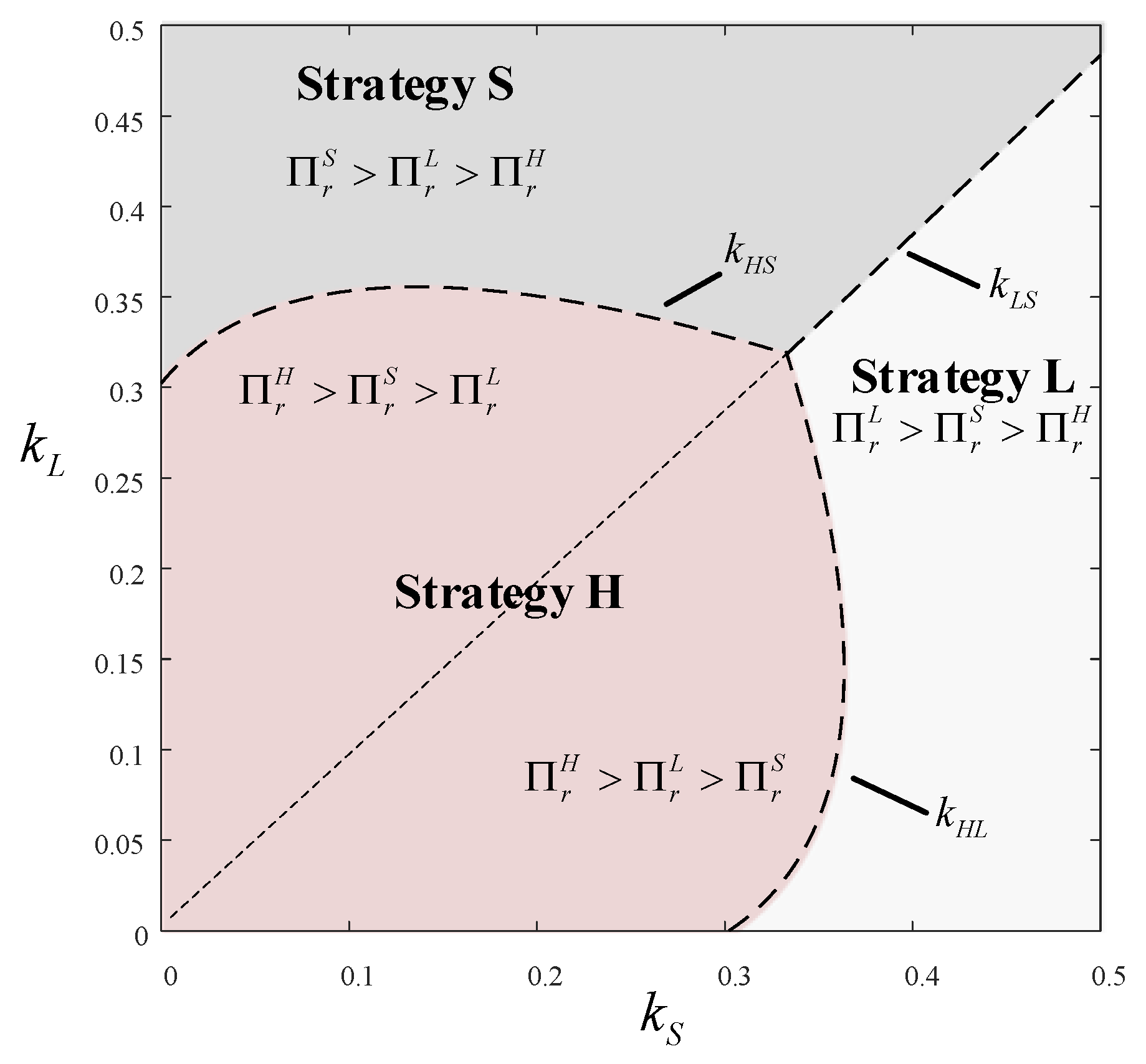

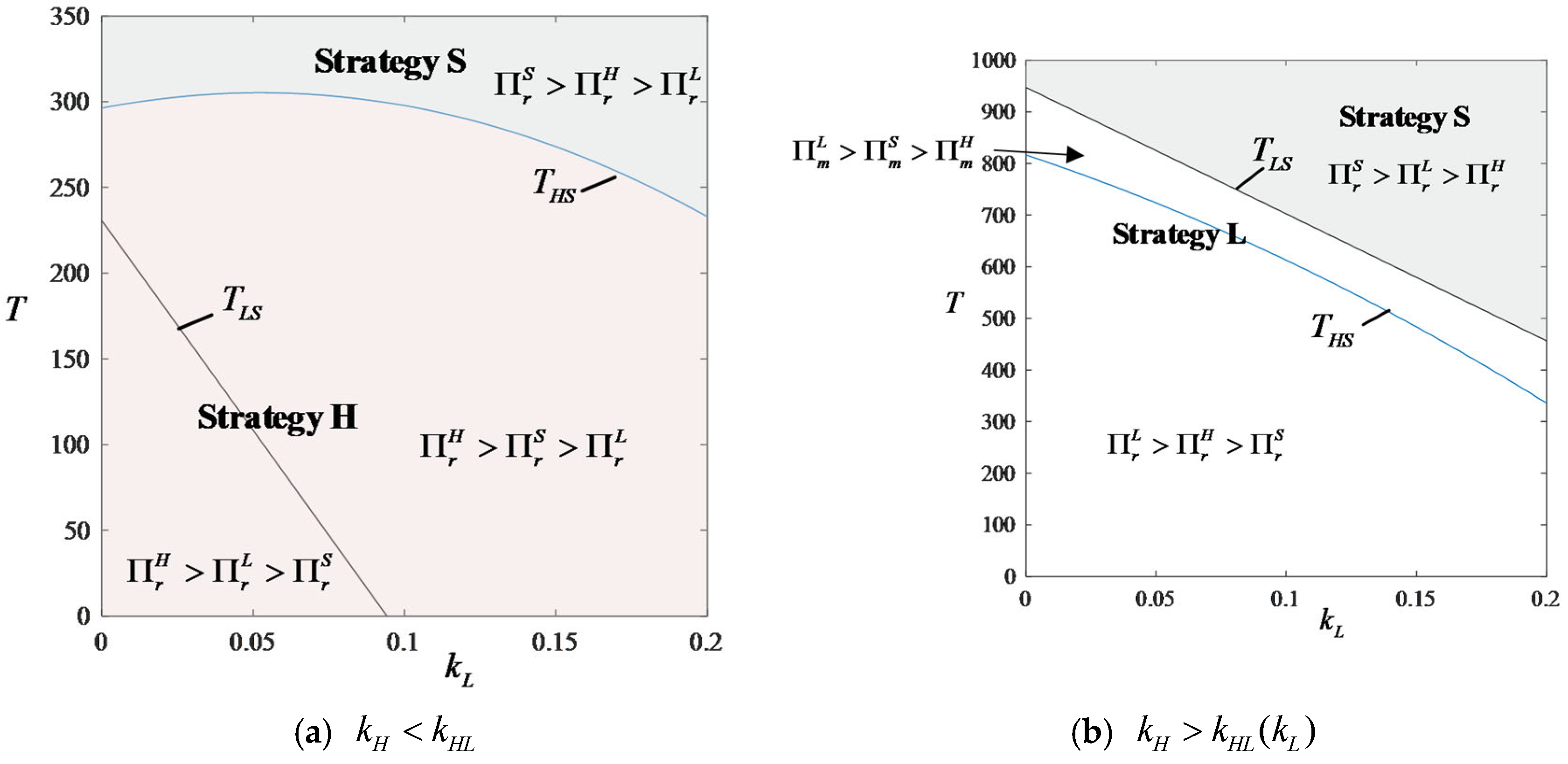

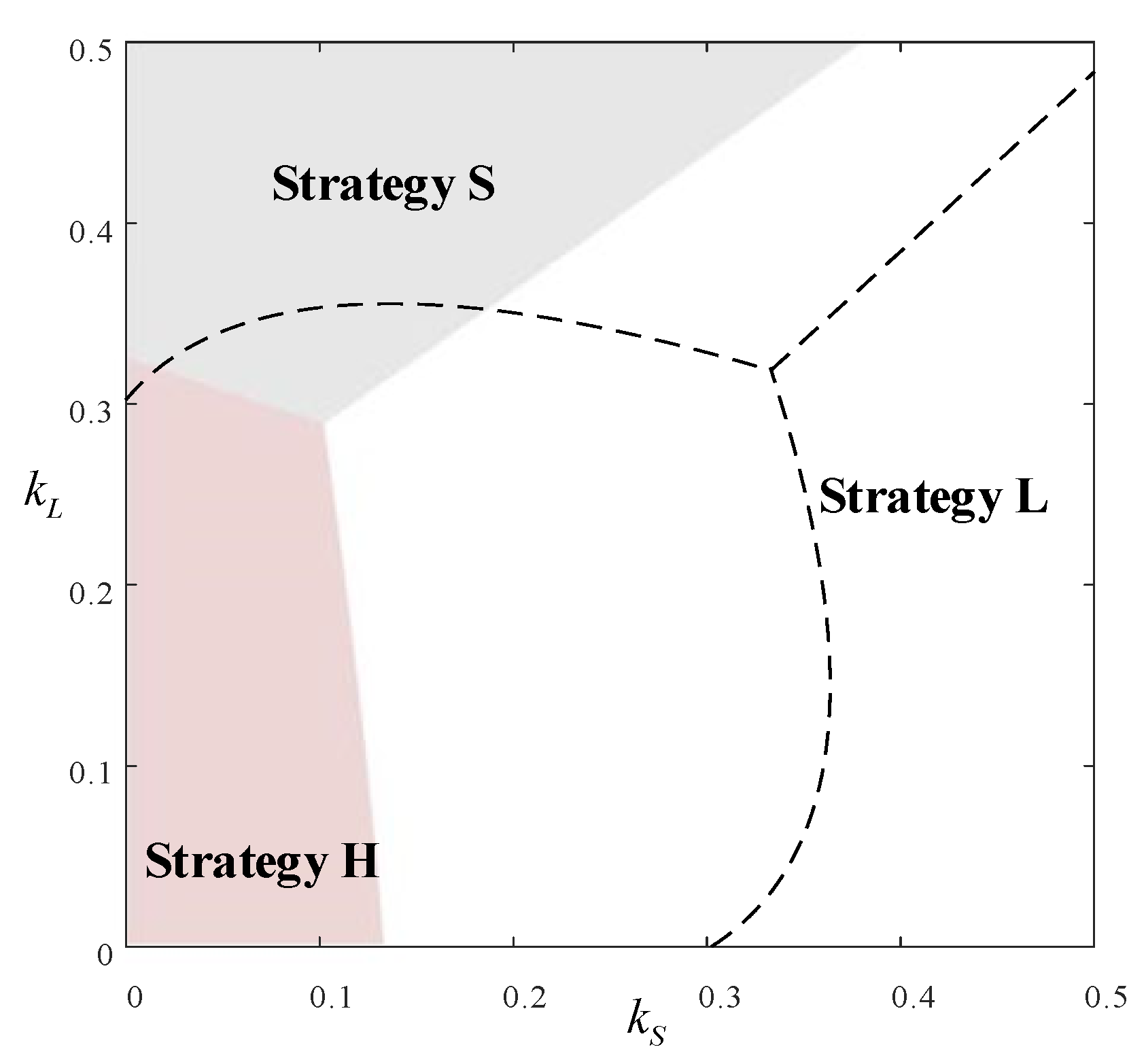

4.2. Analysis of the Retailer’s Strategic Choices

5. Expansion

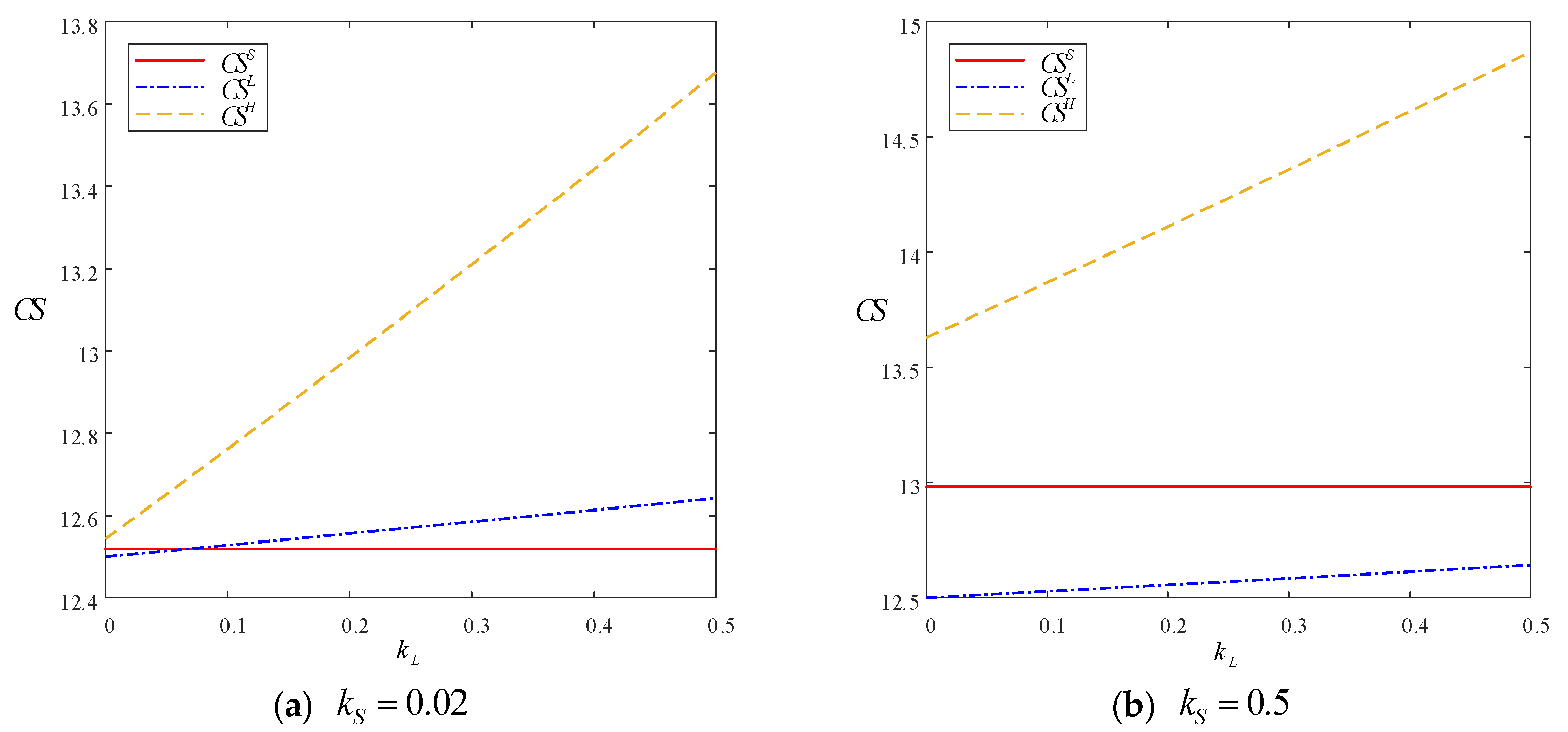

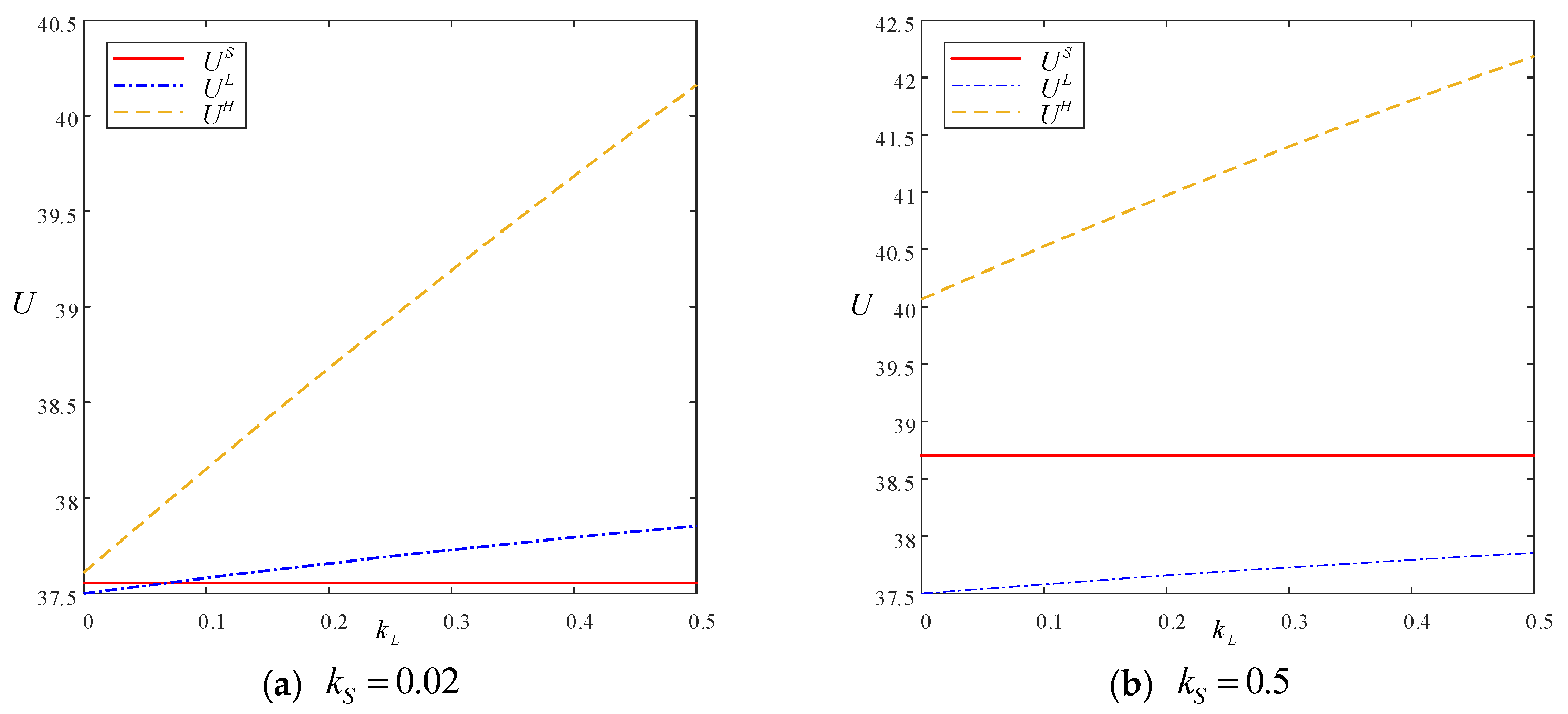

5.1. Consumer Surplus and Social Welfare

5.2. Impact of Fan Quantity

6. Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SVM | short video marketing |

| LSM | live streaming marketing |

| MCN | multichannel networks |

Appendix A. Proofs of Lemmas and Corollaries

- By substituting into and , since and , we can conclude that is a concave function of and that there exists a unique optimal solution. Setting , the optimal solution under Strategy L can be obtained as , where . Notably, because , it is necessary to ensure that holds true.

- By substituting and into the retailer’s demand and profit functions, the optimal demand is obtained, and the optimal profit is obtained. □

- By substituting into and , since and , we can conclude that is a concave function of and that there exists a unique optimal solution. Setting , the optimal solution under Strategy L can be obtained as , where . Notably, because , it is necessary to ensure that holds true.

- By substituting and into the retailer’s demand and profit functions, the optimal demand is obtained, and the optimal profit is obtained. □

- By substituting into , since , we can conclude that is a concave function of and that there exists a unique optimal solution. Setting , the optimal price under Strategy H can be obtained as .

- By substituting into , since the Hessian matrix is negative definite, i.e., since and , we can conclude that is a concave function of and and that there exists a unique optimal solution. Setting , the optimal solution under Strategy H can be obtained as , where . Notably, because , it is necessary to ensure that holds true.

- By substituting , , and into the retailer’s demand and profit functions, the optimal demand is obtained, and the optimal profit is obtained. □

Appendix B. Pairwise Comparisons of the Three Strategies

Appendix C. Proofs of Propositions

- Combining the results of the price comparison, we obtain the following:

- ; therefore, .

- ; therefore, . □

- Combining the results of the profit comparison when , we obtain the following:

- The thresholds for profit comparison are comprehensively compared when and . Thus, when , and ; when , and .

- Therefore, the following synthesis can be obtained:

- Because , , and , while , and are greater than zero, by combining the results of the demand comparison, we can obtain the result of Proposition 5 as follows:

Appendix D. Sensitivity Analysis and Parameter Rationality Explanation

| Parameters | Definition | Bound | Origin | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales price of a retailer’s product | Classical demand function theory (such as linear price-demand relationship) | Refer to Liu et al. [16] | ||

| Number of short videos, reflecting the promotional effort of SVM | The law of diminishing marginal utility | Refer to Cheng et al. [31] | ||

| Promotional effort of LSM | The law of increasing marginal cost | Refer to He et al. [13] | ||

| Potential market size | The active user base of the platform (for example, Douyin‘s clothing market has approximately 120 million users) | Refer to Niu et al. [61] | ||

| Production cost per unit of short video | Cost control for short video production (Clothing category: 500–2000 yuan per video) | Need to ensure that the profit is greater than 0 | ||

| Sensitivity coefficient of consumers to SVM | Suppose consumers are more sensitive to SVM than to LSM (based on user browsing duration data) | Refer to He et al. [14] | ||

| Sensitivity coefficient of consumers to LSM | Assumed that the direct pull effect of LSM’s real-time interactivity on demand is relatively weak | Refer to Zhang et al. [12] | ||

| Commission rate for SVM | The actual commission rate range of the platform (for example, the commission rate of Douyin is usually less 50%) | Refer to Niu et al. [62] | ||

| Commission rate for LSM | The reasons are the same as above. | Refer to Niu et al. [62] | ||

| Mixed commission rate | The reasons are the same as above. | Make assumptions based on the actual situation | ||

| Slotting fee | Distinguish between merchant self-LSM and influencer LSM | Refer to Wang et al. [50] |

References

- CNNIC. The 55nd Statistical Report on the Development of the Internet in China. 2025. Available online: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2025/0117/c88-11229.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Jiang, S.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Ruan, J. Determinants of Buying Produce on Short-Video Platforms: The Impact of Social Network and Resource Endowment-Evidence from China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Engagement That Sells: Influencer Video Advertising on TikTok. Mark. Sci. 2024, 44, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Exploring the factors influencing consumer engagement behavior regarding short-form video advertising: A big data perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C. Way to success: Understanding top streamer’s popularity and influence from the perspective of source characteristics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 36Kr. 2023 Tik Tok Review: 16 Influencers Gained over 10 Million Followers, and 8 Accounts Achieved over 3 Billion yuan in Live-Streaming Sales. 2024. Available online: https://www.36kr.com/p/2629563654225032 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- EWS. Three New Growth Engines Drove the Overall Growth of Tmall’s Double 11 in 2023. 2023. Available online: http://www.news.cn/tech/20231112/6f1bb144ae01480f87101f32cf3622a6/c.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Zhou, C.; Yu, J.; Qian, Y. Should live-streaming platforms nonexclusively promote brands from traditional retail platforms? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 80, 103930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H. Large group decision-making with a rough integrated asymmetric cloud model under multi-granularity linguistic environment. Inf. Sci. 2024, 678, 120994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhang, S. Large group emergency decision-making with bi-directional trust in social networks: A probabilistic hesitant fuzzy integrated cloud approach. Inf. Fusion 2024, 102, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, B.; Zhang, R. Channel strategies for competing retailers: Whether and when to introduce live stream? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 312, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Wang, Z. Live-streaming selling modes on a retail platform. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 173, 103096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Shang, Q.; Pedrycz, W.; Chen, Z.-S. Short video creation and traffic investment decision in social e-commerce platforms. Omega 2024, 128, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Shang, Q.; Chen, Z.-S.; Mardani, A.; Skibniewski, M.J. Short video channel strategy for restaurants in the platform service supply chain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, X.; Chen, Y. Optimal manufacturer strategy for live-stream selling and product quality. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 64, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Gajpal, Y.; Zhang, Z. Optimal channel strategy for an e-seller: Whether and when to introduce live streaming? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 63, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Ji, X.; Wu, J. Retailer’s information sharing and manufacturer’s channel expansion in the live-streaming E-commerce era. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 320, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Mobile Video in the United States-Statistics & Facts. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/2725/mobile-video-in-the-united-states/#topicOverview (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- CSM. The Seventh Annual Research Report on the Value of Short Video Users. 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/fqFdCjHGbb6ynuSQ0OcQvA (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- IIMEDIA. Survey Data on User Behavior in China’s Short Video Industry. 2023. Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c1077/97043.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Chi, X.; Fan, Z.P.; Wang, X.H. Pricing mode selection for the online short video platform. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5105–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAAS. One Million Likes but Less than 5,000 Monthly Sales, What Did the Product Do Wrong in Short Video Marketing? 2020. Available online: https://www.niaogebiji.com/article-36539-1.html (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J. How to improve destination brand identification and loyalty using short-form videos? The role of emotional experience and self-congruity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Q. Empathy with influencers? The impact of the sensory advertising experience on user behavioral responses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xia, H.; Ye, Q. The effect of advertising strategies on a short video platform: Evidence from TikTok. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2022, 122, 1956–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Shi, S.; Filieri, R.; Leung, W.K.S. Short video marketing and travel intentions: The interplay between visual perspective, visual content, and narration appeal. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yan, X. Understanding impulse buying in short video live E-commerce: The perspective of consumer vulnerability and product type. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, H.; Xi, N.; Liao, J.; Yang, Z. Short video marketing: What, when and how short-branded videos facilitate consumer engagement. Internet Res. 2023, 34, 1104–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, M.; Liu, C.; Gull, N. The Influence of Short Video Platform Characteristics on Users’ Willingness to Share Marketing Information: Based on the SOR Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, Q. Characteristics, hotspots, and prospects of short video research: A review of papers published in China from 2012 to 2022. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Su, X.; Yang, B.; Zarifis, A.; Mou, J. Understanding users’ negative emotions and continuous usage intention in short video platforms. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 58, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Lei, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. The relationship between short-form video use and depression among Chinese adolescents: Examining the mediating roles of need gratification and short-form video addiction. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Multimodal cooperative learning for micro-video advertising click prediction. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wu, J.; Ji, X. Consumer environmental preference information sharing with green manufacturer’s short video platform-selling. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Qian, C.; Li, X.; Yuan, Q. How real-time interaction and sentiment influence online sales? Understanding the role of live streaming danmaku. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Xie, X.; Wu, S. An empirical analysis of the impacts of live chat social interactions in live streaming commerce: A topic modeling approach. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 65, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, N.; Huang, L. How the source dynamism of streamers affects purchase intention in live streaming e-commerce: Considering the moderating effect of Chinese consumers’ gender. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Xu, M.; Zheng, Y. Informative or affective? Exploring the effects of streamers’ topic types on user engagement in live streaming commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Guan, X. Live streaming selling strategies of online retailers with spillover effects. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 63, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Zhao, M.; Ren, J.; Hao, Z. Live streaming strategy under multi-channel sales of the online retailer. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 55, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Lai, D.; Pu, X.; Han, G. Self-broadcasting or cooperating with streamers? A perspective on live streaming sales of fresh products. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 64, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bian, Y. Live streaming channel strategy of an online retailer in a supply chain. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 62, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tang, Z. Should manufacturers open live streaming shopping channels? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Mardani, A.; Chen, Z.-S. Live streaming service introduction and optimal contract selection in an e-commerce supply chain. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 8088–8102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Li, G.; Cheng, T.C.E. Friend or foe? Examining local service sharing between offline stores and e-tailers. Omega 2024, 123, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gou, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Does bonus motivate streamers to perform better? An analysis of compensation mechanisms for live streaming platforms. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 164, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodish, L.M.; Abraham, M.; Kalmenson, S.; Livelsberger, J.; Lubetkin, B.; Richardson, B.; Stevens, M.E. How TV advertising works: A meta-analysis of 389 real world split cable TV advertising experiments. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 32, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Eisend, M. Advertising repetition: A meta-analysis on effective frequency in advertising. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqin, T.; Choi, T.-M.; Chung, S.-H. Optimal E-tailing channel structure and service contracting in the platform era. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 160, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Deveci, M.; Delen, D. Maximizing sales: The art of short video creation in livestream e-commerce. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Fan, Z.-P.; Sun, F. Live streaming sales: Streamer type choice and limited sales strategy for a manufacturer. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 61, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhong, F.; Hu, M. Resolving the information reliability issue in live streaming through blockchain adoption. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 189, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, L.; Choi, T.-M.; Cheng, T.C.E. When Is It Wise to Use Blockchain for Platform Operations with Remanufacturing? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 309, 1073–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z. Operation strategy in an E-commerce platform supply chain: Whether and how to introduce live streaming services? Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2022, 31, 1093–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wan, M.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic quality management of live streaming e-commerce supply chain considering streamer type. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, T.; Tayi, G.K. Inroad into omni-channel retailing: Physical showroom deployment of an online retailer. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 283, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, X. Strategic introduction of live-stream selling in a supply chain. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 62, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Ji, L.; Ning, Y.; Li, Y. Influencer selection and strategic analysis for live streaming selling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Z. Fly with the wings of live-stream selling—Channel strategies with/without switching demand. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 3387–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Pricing and Channel Selection Strategies in E-Commerce Supply Chain with Hybrid Channels and Live Streaming. J. Syst. Manag. 2025, 34, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, B.; Dong, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y. Online quality endorsement to improve consumer trust: Blockchain or self-hosted livestream? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Jin, Y. Brands’ livestream selling with influencers’ converting fans into consumers. Omega 2025, 131, 103195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | SVM | LSM | Dual-Channel | Influencer Contract Design | Cost Structure | Demand Form | Competitive Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [15] | × | √ | × | × | × | Nonlinear | × |

| Chen et al. [42] | × | √ | √ | × | Commission + slotting fee | Linear | × |

| Lu et al. [17] | × | √ | √ | × | Commission + slotting fee | Stochastic | Dual-channel competition |

| Wang et al. [44] | × | √ | √ | √ | Commission | × | Dual-channel competition |

| Lu et al. [34] | √ | × | √ | × | Commission | Stochastic | Dual-channel competition |

| He et al. [14] | √ | × | √ | × | Commission + slotting fee | Linear | Dual-channel competition |

| Lei et al. [45] | × | × | √ | × | × | Linear | Co-opetition |

| Zhang et al. [12] | × | √ | × | √ | Commission + slotting fee | Linear | × |

| Yang et al. [46] | × | √ | × | √ | Commission + slotting fee | Nonlinear demand | × |

| Our work | √ | √ | √ | × | Commission + slotting fee | Nonlinear | × |

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Decision variables | |

| Sales price of a retailer’s product | |

| Number of short videos, measured as the total count obtained from the platform’s backend data | |

| Promotional effort of LSM, measured as the proportion of time spent on product demonstrations | |

| Parameters | |

| Potential market size | |

| Production cost per unit of short video | |

| Sensitivity coefficient of consumers to SVM | |

| Sensitivity coefficient of consumers to LSM | |

| Commission rate for SVM | |

| Commission rate for LSM | |

| Mixed commission rate | |

| Slotting fee | |

| Superscripts | |

| S | Short video strategy |

| L | Live streaming strategy |

| H | Hybrid strategy |

| Subscripts | |

| r | Retailer |

| m | MCN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, S.; Yuan, R.; Liu, J. Short Video Marketing or Live Streaming Marketing: Choice of Marketing Strategies for Retailers. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13162675

Feng S, Yuan R, Liu J. Short Video Marketing or Live Streaming Marketing: Choice of Marketing Strategies for Retailers. Mathematics. 2025; 13(16):2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13162675

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Shuai, Rui Yuan, and Jiqiong Liu. 2025. "Short Video Marketing or Live Streaming Marketing: Choice of Marketing Strategies for Retailers" Mathematics 13, no. 16: 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13162675

APA StyleFeng, S., Yuan, R., & Liu, J. (2025). Short Video Marketing or Live Streaming Marketing: Choice of Marketing Strategies for Retailers. Mathematics, 13(16), 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13162675