A Semi-Automatic Framework for Practical Transcription of Foreign Person Names in Lithuanian

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Multi-Stage Approach

- The TTS system needs to identify and to transcribe mixed-language tokens. This poses a challenge, as no off-the-shelf LangID tools are designed to handle such inputs. Addressing this requires developing a specialized LangID system, for which neither pre-defined rules nor training data currently exist.

- For many languages, including Lithuanian, no complete and explicit rule set exists for adapting foreign names—only broad linguistic guidelines are available. Constructing such a rule set would require substantial linguistic expertise and manual effort.

- Error propagation is inherent to multi-stage approaches: mistakes in earlier stages (e.g., misidentified language) are likely to impact subsequent steps, thereby degrading the overall system performance.

1.2. Generative AI Approach

1.3. End-to-End Machine Learning Approach

- Is it possible to develop a fully automated data processing pipeline that converts raw web-crawled data into a dataset of sufficient quality for training practical transcription models?

- What level of transcription accuracy can be achieved using such automatically generated data, and how does this accuracy compare to that of human transcribers?

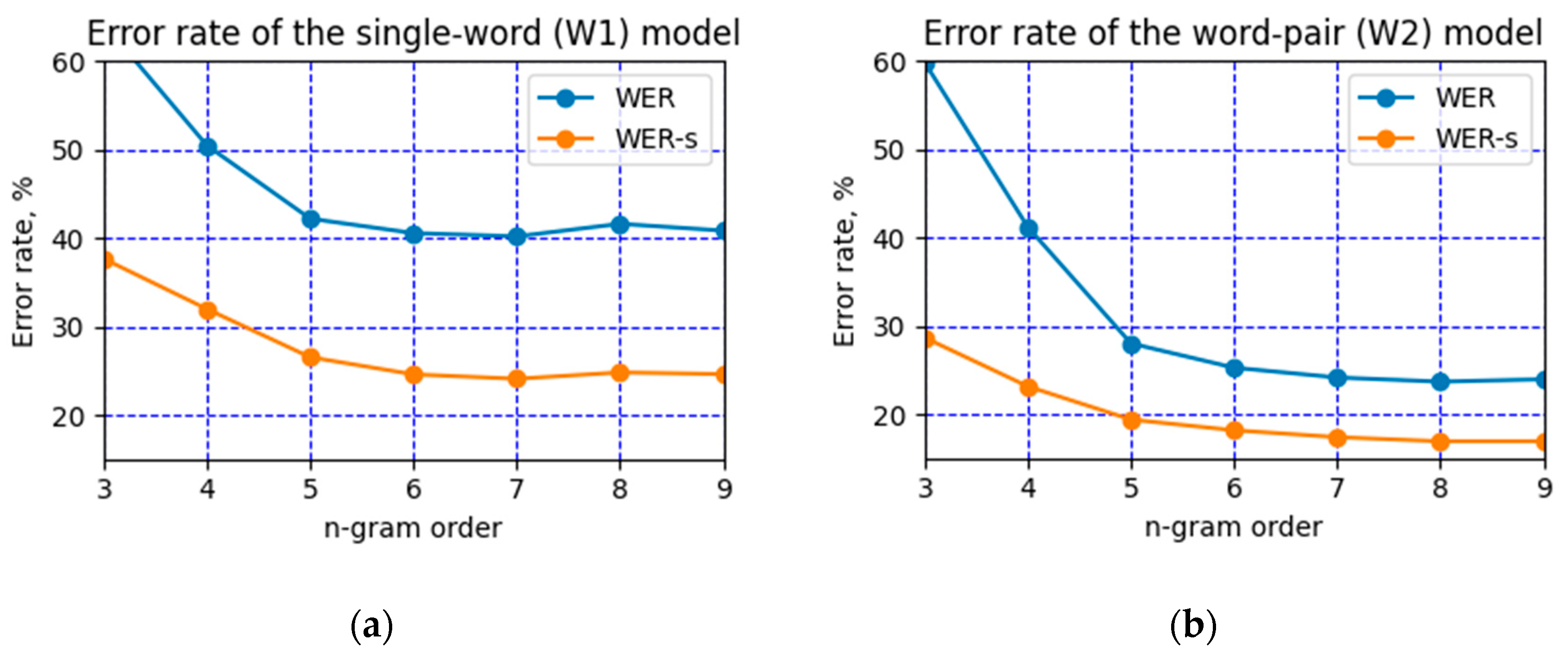

- To what extent do models trained on word pairs outperform those trained on single-word inputs?

- How effective are different data augmentation strategies in enhancing the performance of transcription models?

1.4. Related Work

- We propose a novel semi-automatic data processing pipeline that transforms raw web-crawled data into a training set for practical transcription tasks. This pipeline is demonstrated on Lithuanian—a morphologically rich and challenging language—where it effectively processes, filters, and normalizes data containing inflected and/or mixed-language tokens. The pipeline is potentially fully automatable for languages that do not require modeling of word stress type and location.

- We show that an end-to-end practical transcription model can be trained using this dataset, despite residual noise in the processed data. Although exact word error rate (WER) estimation is hindered by noisy reference labels in the test set, we report an upper-bound WER of approximately 19%, with the actual performance likely being significantly better—potentially nearly half that value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

[[:upper:]][-\x27[:lower:]]+\s+[[:upper:]][-\x27[:lower:]]+\s+\( [[:upper:]][-\x27[:lower:]]+\s+[[:upper:]][-\x27[:lower:]]+\s*\)

- Unintended Matches: The regular expression sometimes captured pairs of proper nouns that were not person names and their transcriptions, but rather unrelated entities, such as person–location, person–actor, person–sports team, or location–location combinations (see Table 2, rows 1–5).

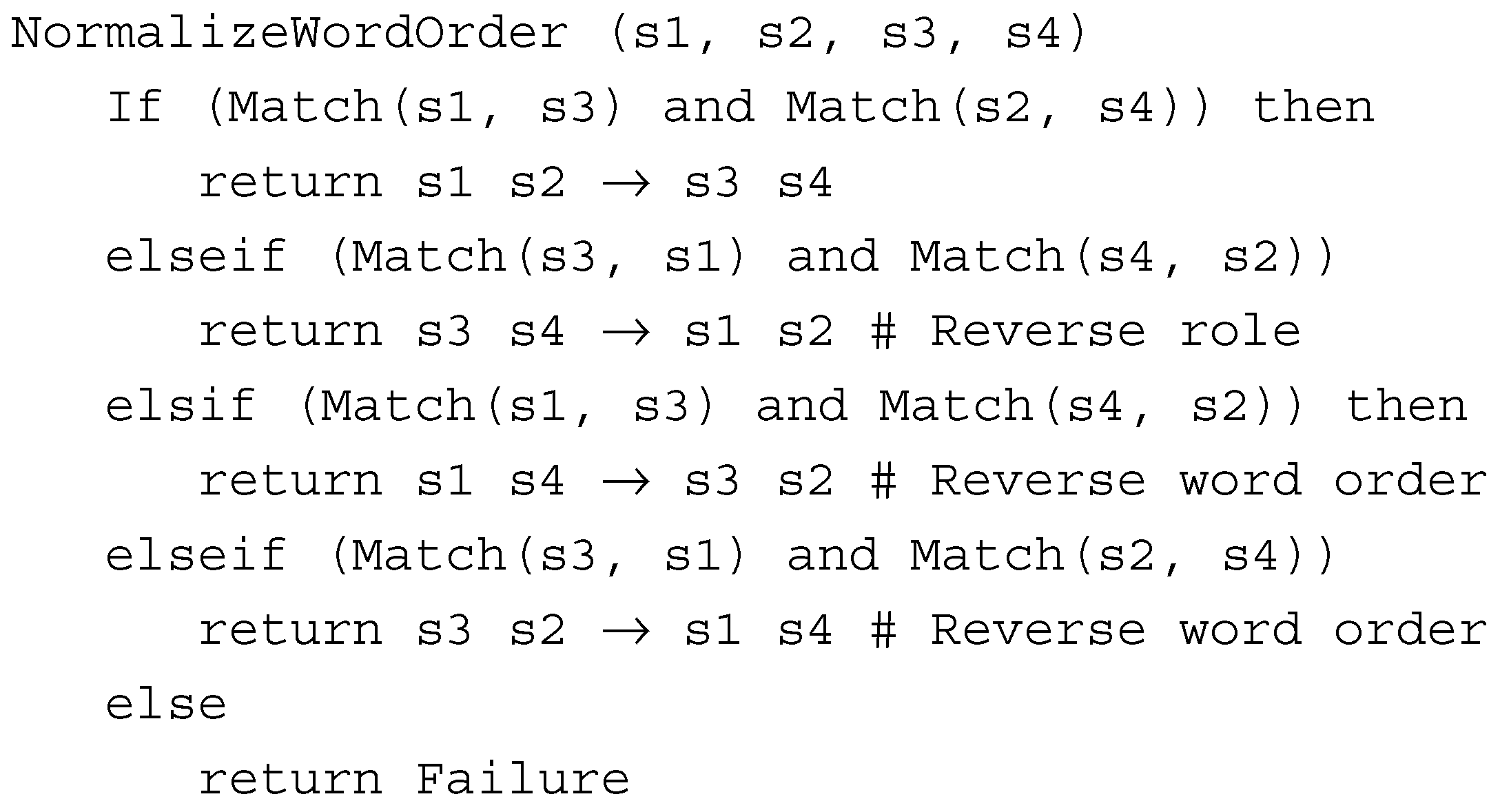

- Word Order Inversion: The word order in one of the name pairs was sometimes reversed relative to the other (see Table 2, row 8).

- Inflection Mismatch: The original name with concatenated or fused inflectional suffixes could be in a different grammatical case than the transcribed name. For instance, the original name Alexis Tsipras is in the nominative, while the transcription Aleksiui Ciprui is in the dative case (Table 2, row 15). Particularly challenging were these mismatches when intertwined with role inversion. For example, the name pair Alberto Alonso (Table 2, row 16) could be interpreted as a non-inflected original form, an adapted original form (e.g., genitive of Albert Alons), or a transcription in the genitive case.

- Multiple Inflections: A single non-inflected original name could correspond to multiple transcriptions, each in a different grammatical case depending on the context (Table 2, rows 11–14).

- Inconsistent Labeling and Human Errors: Different transcriptions of the same original name were observed due to the varying linguistic knowledge of human editors (Table 2, rows 17–19). Additionally, spelling errors appeared in both original names (Table 2, row 20) and transcriptions (Table 2, row 21).

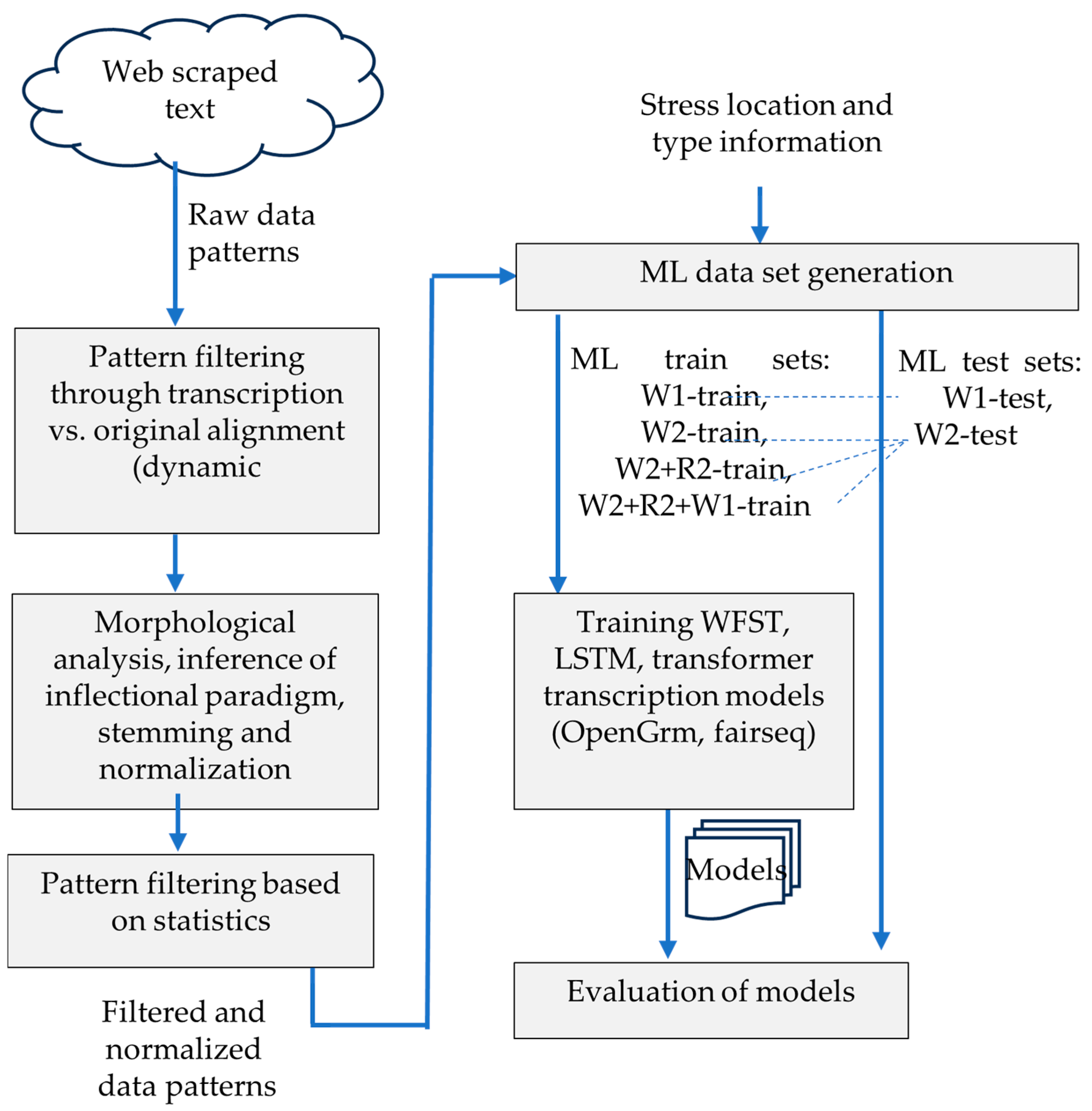

2.2. Method

- Preprocessing and cleaning of web-scraped data, including filtering, normalization, and reordering of raw data patterns.

- Adding word stress location and type information to the cleaned data.

- Generation of multiple training sets, based on different configurations and augmentation strategies.

- Training of machine learning models, using a range of architectures and training setups and evaluation of their accuracy on held-out test data.

2.2.1. Data Preprocessing

2.2.2. Gathering Stress Data

2.2.3. Generating Training and Test Sets

2.2.4. Training Transcription Models

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Model Accuracy

3.2. Detailed Error Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Alternative approaches. Exploring alternative approaches to the practical transcription problem, as introduced in Section 1.1 and Section 1.2, remains a promising direction for future work. The Generative AI approach may yield acceptable performance in handling mixed-language tokens, particularly when pre-trained large language models (LLMs) are fine-tuned or instruction-tuned for this specific task. Within the end-to-end machine learning framework, LLMs could also assist in cleaning and normalizing raw data patterns. Furthermore, LLMs may be employed to extract supplementary features—such as speaker nationality or linguistic background—which could enhance the predictive performance of transcription models.

- Stress modeling. This study incorporated several arbitrary choices regarding stress modeling. Stress placement was integrated into the end-to-end system, with the stress mark encoded as an additional ASCII symbol following the stressed character. An alternative approach would be to treat stress placement as an independent machine learning task. The stress mark could be embedded within an accented character, forming a single output symbol. This strategy would expand the output symbol set rather than increase the length of the output sequence. Additionally, weak supervision techniques [44] or semi-supervised [45] stress modeling approaches could be explored to partially automate this task.

- Experimenting with the dataset. It is important to continue manual cleaning of the test set to establish a fully curated, gold-standard benchmark, thereby increasing confidence in the accuracy estimates. The dataset could also be enriched with longer name sequences (e.g., three or more words) to better reflect the diversity of naming conventions. Additionally, since morphological analysis is already a component of the data processing pipeline, the dataset could be augmented with inflected forms of names not originally present. For example, from the nominative form Charlesas Darwinas → Čarlzas Darvinas, one could derive genitive forms such as Charles’o Darwin’o → Čarlzo Darvino or dative forms such as Charlesui Darwinui → Čarlzui Darvinui.

- Improving data filtering. The current alignment procedure appears overly permissive. Although stricter alignment criteria may require additional linguistic resources, a promising improvement would be to assign language labels to each permitted substitution. This would restrict substitutions to those within the same language set, potentially enhancing data consistency, filtering precision, and overall transcription accuracy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WFST | Weighted Finite State Transducer |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| WER | Word Error Rate |

| WER-s | Stress-compensated Word Error Rate |

| TTS | Text-to-Speech |

| G2P | Grapheme-to-Phoneme |

| LangID | Language identification task |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| IPA | International Phonetic Alphabet |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ASCII | American character encoding standard |

Appendix A

| Task | EEL | EHL | DEL | DHL | Batch Size | Dropout Rate | WER, % | WER-s, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 29.13 ± 0.85 | 22.99 ± 0.76 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 26.95 ± 0.29 | 21.22 ± 0.18 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 27.88 ± 0.43 | 21.51 ± 0.48 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 28.44 ± 0.29 | 22.33 ± 0.19 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 27.90 ± 0.19 | 22.42 ± 0.19 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 27.50 ± 0.39 | 21.96 ± 0.35 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 28.65 ± 0.14 | 22.46 ± 0.20 | |

| W1 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 25.49 ± 0.25 | 19.81 ± 0.22 |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 27.98 ± 0.59 | 21.95 ± 0.45 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 27.85 ± 0.21 | 21.71 ± 0.19 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 29.35 ± 0.52 | 23.20 ± 0.54 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 27.73 ± 0.61 | 21.32 ± 0.54 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 28.26 ± 0.31 | 21.69 ± 0.28 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 26.83 ± 0.43 | 21.16 ± 0.44 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 28.84 ± 0.26 | 22.17 ± 0.26 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 27.22 ± 0.55 | 21.27 ± 0.59 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 21.58 ± 0.36 | 17.31 ± 0.29 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 21.31 ± 0.14 | 16.39 ± 0.09 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 21.70 ± 0.39 | 16.89 ± 0.32 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 21.88 ± 0.32 | 17.10 ± 0.17 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 20.59 ± 0.24 | 16.77 ± 0.18 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 19.98 ± 0.19 | 16.19 ± 0.14 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 21.12 ± 0.25 | 17.10 ± 0.22 | |

| W2 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 20.81 ± 0.30 | 16.47 ± 0.22 |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 21.60 ± 0.18 | 17.56 ± 0.13 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 20.65 ± 0.40 | 16.14 ± 0.25 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 21.53 ± 0.25 | 17.49 ± 0.27 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 21.46 ± 0.07 | 16.90 ± 0.09 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 20.83 ± 0.16 | 17.11 ± 0.17 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 20.47 ± 0.27 | 16.90 ± 0.24 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 21.48 ± 0.29 | 17.34 ± 0.24 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 20.60 ± 0.20 | 16.41 ± 0.09 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 20.01 ± 0.16 | 16.22 ± 0.14 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 20.78 ± 0.14 | 16.44 ± 0.09 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 20.26 ± 0.13 | 16.52 ± 0.22 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 20.78 ± 0.09 | 16.39 ± 0.06 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 20.06 ± 0.14 | 16.48 ± 0.13 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 19.04 ± 0.18 | 15.66 ± 0.12 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 20.19 ± 0.27 | 16.49 ± 0.24 | |

| W2+R2 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 19.54 ± 0.20 | 16.15 ± 0.08 |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 20.20 ± 0.24 | 16.69 ± 0.21 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 20.02 ± 0.13 | 16.12 ± 0.13 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 20.49 ± 0.32 | 16.68 ± 0.32 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 20.35 ± 0.18 | 16.25 ± 0.14 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 19.73 ± 0.19 | 16.24 ± 0.16 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 19.57 ± 0.22 | 16.40 ± 0.19 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 20.28 ± 0.30 | 16.55 ± 0.25 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 19.96 ± 0.08 | 16.43 ± 0.10 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 19.83 ± 0.21 | 16.25 ± 0.23 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 20.92 ± 0.06 | 16.53 ± 0.02 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 20.07 ± 0.11 | 16.42 ± 0.08 | |

| 128 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 20.91 ± 0.07 | 16.70 ± 0.06 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 19.68 ± 0.19 | 16.70 ± 0.17 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 19.58 ± 0.05 | 16.02 ± 0.08 | |

| 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 19.30 ± 0.17 | 16.16 ± 0.17 | |

| W2+R2+R1 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 19.86 ± 0.12 | 16.26 ± 0.09 |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.1 | 19.95 ± 0.23 | 16.28 ± 0.08 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 0.3 | 20.12 ± 0.16 | 16.25 ± 0.06 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.1 | 20.14 ± 0.22 | 16.38 ± 0.25 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 1024 | 0.3 | 20.55 ± 0.12 | 16.58 ± 0.13 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.1 | 20.16 ± 0.11 | 16.77 ± 0.07 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 0.3 | 19.51 ± 0.15 | 16.30 ± 0.12 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.1 | 19.96 ± 0.11 | 16.62 ± 0.08 | |

| 256 | 1024 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.3 | 19.51 ± 0.17 | 16.26 ± 0.15 |

Appendix B

| Occ. | Original | Reference | Prediction | Golden Standard | Ref. Cat | Pred. Cat. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Alexį Tsiprą | Alèksį Cìprą | Ãleksį Cìprą | 0 | m | |

| 5 | Alexio Tsipro | Alèksio Tsìpro | Alèksijo Cìpro | Alèksio Cìpro | s | s |

| 60 | Alexio Tsipro | Alèksio Cìpro | Alèksijo Cìpro | 0 | s | |

| 19 | Alexis Tsipras | Alèksis Tsìpras | Alèksis Cìpras | s | 0 | |

| 5 | Ali Zeidanas | Ãli Zeidãnas | Alì Zeidãnas | Ãli Zeĩdenas | m | m |

| 6 | Amy Poehler | Eĩmi Poũler | Eĩmi Pèler | 0 | l | |

| 6 | Andrea Bocelli | Andrèa Bočèli | Andrė̃ja Bočèli | 0 | s | |

| 14 | Anna Wintour | Ãna Viñtur | Ãna Vintùr | 0 | s | |

| 11 | Bambangas Soelistyo | Bambángas Sulìstjo | Bambángas Soelìsto | Bembéngas Sulìstjo | m | l |

| 10 | Blake Lively | Bleĩk Láivli | Bleĩk Lìvli | 0 | l | |

| 6 | Brendan Gilligan | Bréndan Gìligan | Bréndan Džìligan | 0 | l | |

| 9 | Buzz Aldrin | Bãz Òldrin | Bùz Áldrin | Bàz Òldrin | s | l |

| 5 | Buzzas Aldrinas | Bãzas Òldrinas | Bùzas Al̃drinas | Bàzas Òldrinas | s | l |

| 14 | Carlos Delfino | Kárlos Delfìno | Kárlos Del̃fino | 0 | m | |

| 9 | Caroline Kennedy | Kèrolain Kènedi | Karolìn Kènedi | 0 | l | |

| 6 | Carrie Prejean | Kèri Preidžán | Kèri Prežán | m | 0 | |

| 6 | Chris Cassidy | Krìs Kãsidi | Krìs Kẽsidi | m | 0 | |

| 10 | Cindy Crawford | Siñdi Kráuford | Siñdi Kroũford | Siñdi Krõford | s | s |

| 13 | Cindy Crawford | Siñdi Kròford | Siñdi Kroũford | Siñdi Krõford | s | s |

| 8 | David Lynch | Deĩvid Liñč | Deĩvid Lỹnč | 0 | s | |

| 10 | Dilmai Rousseff | Dìlmai Rùsef | Dil̃mai Rùsef | Dil̃mai Rusèf | s | s |

| 101 | Donald Tusk | Dònald Tùsk | Dònald Tãsk | 0 | l | |

| 5 | Donaldas Tuskas | Dònaldas Tùskas | Dònaldas Tãskas | 0 | l | |

| 5 | Ene Ergma | Èn Èrgma | Èn Er̃gma | Ène Èrgma | l | l |

| 5 | Geir Lundestad | Geĩr Luñdestad | Geĩr Liùndestad | 0 | s | |

| 6 | Yingluck Shinawatra | Jiñglak Činavãta | Iñglak Šinavãtra | Jiñglak Šinavãtra | l | s |

| 15 | Yingluck Shinawatra | Jinglùk Šinavãtra | Iñglak Šinavãtra | Jiñglak Šinavãtra | m | s |

| 5 | Yingluck Shinawatros | Jiñglak Činavãtos | Iñglak Šinavãtos | Jiñglak Šinavãtros | l | l |

| 5 | Yukio Edano | Jùkio Edãno | Jùkijo Edãno | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | Jean Sibelius | Ján Sibèlijus | Žán Sibèlijus | l | 0 | |

| 5 | Jeanui Monnet | Žãnui Monè | Žãnui Monė̃ | s | 0 | |

| 8 | Jennifer Hudson | Džènifer Hãdson | Džènifer Hàdson | s | 0 | |

| 6 | Jerry Rubin | Džèri Rùbin | Džèri Rãbin | 0 | l | |

| 5 | Jiroemonas Kimura | Džiroemònas Kimùra | Žirumònas Kimùra | 0 | l | |

| 8 | Joakim Noah | Žoakìm Nòa | Joakìm Nòa | Džoũakim Noũa | l | l |

| 8 | Johnas Kirby | Džònas Kir̃bi | Džònas Ker̃bi | s | 0 | |

| 10 | Johno Kirby | Džòno Ker̃bi | Džòno Kir̃bi | 0 | s | |

| 14 | Jose Mujica | Chosė̃ Muchìka | Chosė̃ Mužìka | 0 | l | |

| 6 | Josephas Muscatas | Džòzefas Muskãtas | Džòzefas Maskãtas | Džoũzefas Maskãtas | m | s |

| 5 | Juan Carlos | Chuán Kárl | Chuán Kárlos | l | 0 | |

| 6 | Kei Nishikori | Kèi Nišikòri | Keĩ Nišikòri | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | Kemalis Kilicdaroglu | Kemãlis Kiličdaròhlu | Kemãlis Kilikdaròhlu | 0 | l | |

| 5 | Kenneth Campbell | Kènet Kémbel | Kènet Kémpbel | 0 | s | |

| 6 | Kerem Gonlum | Kerèm Geñlium | Kerèm Gònlam | 0 | l | |

| 17 | Kianoushas Jahanpouras | Ki-ãnušas Džahanpū̃ras | Ki-ãnušas Džahanpùras | Ki-anùšas Džahanpū̃ras | s | m |

| 10 | Konrad Adenauer | Kònrad Ãdenauer | Kònrad Adenáuer | 0 | s | |

| 5 | Kurt Vonnegut | Kùrt Vònegut | Kùrt Fònegut | Kùrt Vãnegat | m | l |

| 12 | Lance Stephenson | Leñs Stèfenson | Leñs Stìvenson | Leñs Stỹvenson | l | s |

| 14 | Laurent Gbagbo | Lòren Gbãgbo | Lorán Gbãgbo | Lorán Gbagbò | s | s |

| 9 | Laurent’as Fabiusas | Lorãnas Fãbijusas | Lorãnas Fabiùsas | s | 0 | |

| 21 | Lech Walesa | Lèch Valènsa | Lèch Valèsa | 0 | l | |

| 5 | Lechą Walesą | Lèchą Valènsą | Lèchą Valèsą | 0 | l | |

| 30 | Lechas Walesa | Lèchas Valènsa | Lèchas Valèsa | 0 | l | |

| 10 | Lecho Walesos | Lècho Valènsos | Lècho Valèsos | 0 | l | |

| 6 | Mariah Carey | Marãja Kèri | Marìja Kèri | Merãja Kèri | s | l |

| 18 | Mariah Carey | Merãja Kèri | Marìja Kèri | 0 | l | |

| 12 | Marie Trintignant | Marì Trentinján | Marỹ Trintinján | Marỹ Trentinján | s | s |

| 6 | Marisol Touraine | Marizòl Tureñ | Marisòl Turèn | m | 0 | |

| 6 | Marissa Mayer | Marìsa Mèjer | Marìsa Mãjer | s | 0 | |

| 10 | Marlon Brando | Mar̃lon Brándo | Mar̃lon Breñdo | Márlon Bréndou | s | s |

| 11 | Michel Hazanavicius | Mišèl Hazanãvičius | Mišèl Azanãvičius | s | 0 | |

| 6 | Milton Friedman | Mil̃ton Friẽdman | Mil̃ton Frìdman | Mil̃ton Frỹdmen | l | m |

| 6 | Milton Friedman | Mil̃ton Frỹdman | Mil̃ton Frìdman | Mil̃ton Frỹdmen | s | m |

| 16 | Monta Ellis | Mònta Èlis | Mònta Ẽlis | Mòntei Èlis | s | m |

| 6 | Navi Pillay | Nãvi Piláj | Nãvi Pilái | Nãvi Pìlei | m | m |

| 23 | Nene Hilario | Nèn Ilãrijo | Nèn Hìlario | Nenè Ilãriju | l | l |

| 10 | Nicki Minaj | Nìki Minãdž | Nìki Minãj | Nìki Minãž | l | l |

| 65 | Oprah Winfrey | Òpra Vìnfri | Òpra Viñfri | Òupra Viñfri | m | m |

| 7 | Peter Hess | Pẽter Hès | Pìter Hès | m | 0 | |

| 6 | Peteris Altmaieris | Pė̃teris Áltmajeris | Pė̃teris Altmãjeris | 0 | s | |

| 6 | Peteris Lerneris | Pìteris Ler̃neris | Pė̃teris Ler̃neris | 0 | l | |

| 7 | Peteris Szijjarto | Pė̃teris Sìjarto | Pė̃teris Šidžárto | 0 | l | |

| 6 | Pol Pot | Pòl Pòt | Põl Pòt | 0 | s | |

| 7 | Prabowo Subianto | Prãbovo Subi-ánto | Prabòvo Subi-ánto | s | 0 | |

| 5 | Prosper Merimee | Pròsper Merìm | Pròsper Merìmi | Prospèr Merimė̃ | l | l |

| 10 | Raffaele Sollecito | Rafaèl Solečìto | Rafaèl Solesìto | Rafaèle Solèčito | m | l |

| 6 | Ralphas Fiennesas | Rálfas Fáinsas | Rálfas Fi-ènesas | Reĩfas Fáinzas | l | l |

| 10 | Ryan Toolson | Raján Tū̃lson | Raján Tùlson | Rãjan Tū̃lson | m | m |

| 18 | Sabine Kehm | Sabìn Kė̃m | Sabìn Kèm | Zabỹne Kė̃m | l | l |

| 6 | Sakellie Daniels | Sakelì Dẽni-els | Sakelì Dãni-els | Sakèli Dẽni-els | s | s |

| 5 | Salma Hayek | Sèlma Hãjek | Sálma Hãjek | 0 | m | |

| 6 | Salvador Allende | Salvadòr Aljènd | Salvadòr Alènd | Salvadòr Aljènde | l | l |

| 4 | Salvadoras Allende | Salvadòras Aljènd | Salvadòras Alènd | Salvadòras Aljènde | l | l |

| 5 | Samantha Murray | Samánta Miurė̃j | Samánta Mùrėj | 0 | m | |

| 19 | Sergio Mattarella | Ser̃džijo Matarèla | Ser̃chijo Matarèla | 0 | l | |

| 4 | Shuji Nakamura | Šiùdži Nakamùra | Šùdži Nakamùra | s | 0 | |

| 6 | Syd Barrett | Sìd Bãret | Sáid Bãret | Sìd Bẽret | s | l |

| 9 | Silvio Berlusconi | Sìlvijo Berluskòni | Sil̃vijo Berluskòni | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | Simon Frekley | Sáimon Frìkli | Sáimon Frèkli | s | 0 | |

| 4 | Stephenas Mullas | Stìvenas Mãlas | Stìvenas Màlas | Stỹvenas Màlas | s | s |

| 9 | Steve Wozniak | Stìv Vòzniak | Stỹv Vòzniak | s | 0 | |

| 7 | Steven Theede | Stỹven Tỹd | Stìven Tìd | 0 | s | |

| 4 | Taneras Yildizas | Tãneras Jildìzas | Tanèras Jildìzas | 0 | s | |

| 14 | Thomas Hobbes | Tòmas Hòbs | Tòmas Hòbes | Tòmas Hòbz | s | l |

| 19 | Timothy Geithner | Tìmoti Gáitner | Tìmoti Geĩtner | 0 | l | |

| 13 | Valerie Trierweiler | Valerì Trìjerveler | Valerì Trỹrvailer | Valerỹ Trijervailèr | m | m |

| 28 | Valerie Trierweiler | Valerì Trirveĩler | Valerì Trỹrvailer | Valerỹ Trijervailèr | m | m |

| 4 | Vitaly Kamluk | Vitãli Kamliùk | Vitãli Kamlùk | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | Woodrow Wilson | Vùdrov Vìlson | Vùdrou Vìlson | s | 0 | |

| 5 | Woodrow Wilsono | Vùdrau Vìlsono | Vùdrou Vìlsono | s | 0 |

References

- McArthur, T. Transliteration. In Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/transliteration (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Superanskaja, A.V. Teoreticheskie Osnovy Prakticheskoj Transkripcii [Theoretical Foundations of Practical Transcription], 2nd ed.; LENAND: Moscow, Russia, 2018; pp. 10–40. Available online: https://archive.org/details/raw-..-2018/page/1/mode/2up (accessed on 7 May 2025). (In Russian)

- Lui, M.; Baldwin, T. langid.py: An off-the-shelf language identification tool. In Proceedings of the ACL 2012 System Demonstrations, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 9–11 July 2012; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Joulin, A.; Grave, E.; Bojanowski, P.; Mikolov, T. Bag of tricks for efficient text classification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1607.01759. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.01759 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Google. Compact Language Detector v3 (CLD3). Available online: https://github.com/google/cld3 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Papariello, L. XLM-Roberta-Base Language Detection. Hugging Face. 2021. Available online: https://huggingface.co/papluca/xlm-roberta-base-language-detection (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Apple. Language Identification from Very Short Strings. Apple Machine Learning Research. 2019. Available online: https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/language-identification-from-very-short-strings (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Toftrup, M.; Sørensen, S.A.; Ciosici, M.R.; Assent, I. A reproduction of Apple’s bi-directional LSTM models for language identification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.06282. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.06282 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Moillic, J.; Ismail Fawaz, H. Language Identification for Very Short Texts: A review. Medium. 2022. Available online: https://medium.com/besedo-engineering/language-identification-for-very-short-texts-a-review-c9f2756773ad (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Kostelac, M. Comparison of Language Identification Models. ModelPredict. 2021. Available online: https://modelpredict.com/language-identification-survey (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- International Phonetic Association. Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.08774 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Finetuned language models are zero-shot learners. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.01652. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.01652 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02155. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Zhang, S.; Liang, Y.; Shin, R.; Chen, M.; Du, Y.; Li, X.; Ram, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T.; Finn, C. Instruction tuning for large language models: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.10792. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.10792 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Ainsworth, W. A system for converting English text into speech. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 1973, 21, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elovitz, H.; Johnson, R.; McHugh, A.; Shore, J. Letter-to-sound rules for automatic translation of English text to phonetics. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1976, 24, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divay, M.; Vitale, A.J. Algorithms for grapheme-phoneme translation for English and French: Applications for database searches and speech synthesis. Comput. Linguist. 1997, 23, 495–523. [Google Scholar]

- Damper, R.I.; Eastmond, J.F. A comparison of letter-to-sound conversion techniques for English text-to-speech synthesis. Comput. Speech Lang. 1997, 11, 33–73. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, A.; Sumita, E. Phrase-based machine transliteration. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Technologies and Corpora for Asia-Pacific Speech Translation, Hyderabad, India, 11 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2014, Montreal, Canada, 8–11 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, J.; Auli, M.; Grangier, D.; Dauphin, Y.N. Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. In Proceedings of the ICML 2017, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Schuster, M.; Le, Q.V.; Krikun, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Thorat, N.; Viégas, F.; Wattenberg, M.; Corrado, G.; et al. Google’s multilingual neural machine translation system: Enabling zero-shot translation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneau, A.; Lample, G.; Ranzato, M.; Denoyer, L.; Jégou, H. Unsupervised cross-lingual representation learning at scale. In Proceedings of the ACL 2020, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 8440–8451. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-main.747/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Luong, M.T.; Pham, H.; Manning, C.D. Effective approaches to attention-based neural machine translation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–21 September 2015; pp. 1412–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Cotterell, R.; Kirov, C.; Sylak-Glassman, J.; Walther, G.; Vylomova, E.; McCarthy, A.D.; Kann, K.; Mielke, S.J.; Nicolai, G.; Silfverberg, M.; et al. The CoNLL–SIGMORPHON 2018 Shared Task: Universal Morphological Reinflection. In Proceedings of the CoNLL–SIGMORPHON 2018 Shared Task, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–1 November 2018; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Cotterell, R.; Hulden, M. Applying the transformer to character-level transduction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.10213. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, K.; Ashby, L.F.E.; Goyzueta, A.; McCarthy, A.; Wu, S.; You, D. The SIGMORPHON 2020 Shared Task on Multilingual Grapheme-to-Phoneme Conversion. In Proceedings of the 17th SIGMORPHON Workshop on Computational Research in Phonetics, Phonology, and Morphology, Online, 10 July 2020; pp. 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Raškinis, G. Transliteration List of Foreign Person Names into Lithuanian v.1; CLARIN-LT: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2025; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11821/68 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Norkevičius, G.; Raškinis, G.; Kazlauskienė, A. Knowledge-based grapheme-to-phoneme conversion of Lithuanian words. In Proceedings of the SPECOM 2005, 10th International Conference Speech and Computer, Patras, Greece, 17–19 October 2005; pp. 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskienė, A.; Raškinis, G.; Vaičiūnas, A. Automatinis Lietuvių Kalbos žodžių Skiemenavimas, Kirčiavimas, Transkribavimas [Automatic Syllabification, Stress Assignment and Phonetic Transcription of Lithuanian Words]; Vytautas Magnus University: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2010; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12259/254 (accessed on 15 April 2025). (In Lithuanian)

- Kirčiuoklis—A Tool for Placing Stress Marks on Lithuanian Words. Available online: https://kalbu.vdu.lt/mokymosi-priemones/kirciuoklis/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Novak, J.R.; Minematsu, N.; Hirose, K. Phonetisaurus: Exploring grapheme-to-phoneme conversion with joint n-gram models in the WFST framework. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2016, 22, 907–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Hidden Markov models for grapheme to phoneme conversion. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2005, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–8 September 2005; pp. 1973–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.L.; Ashby, L.F.E.; Garza, M.E.; Lee-Sikka, Y.; Miller, S.; Wong, A.; McCarthy, A.D.; Gorman, K. Massively multilingual pronunciation mining with WikiPron. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; pp. 4216–4221. [Google Scholar]

- Viterbi, A.J. Error bounds for convolutional codes and an asymptotically optimum decoding algorithm. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roark, B.; Sproat, R.; Allauzen, C.; Riley, M.; Sorensen, J.; Tai, T. The OpenGrm open-source finite-state grammar software libraries. In Proceedings of the ACL 2012 System Demonstrations, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 9–11 July 2012; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Allauzen, C.; Riley, M.; Schalkwyk, J.; Skut, W.; Mohri, M. OpenFst: A general and efficient weighted finite-state transducer library. In Proceedings of the CIAA, Prague, Czech Republic, 16–18 July 2007; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, K. Pynini: A Python library for weighted finite-state grammar compilation. In Proceedings of the SIGFSM Workshop on Statistical NLP and Weighted Automata, Berlin, Germany, 12 August 2016; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, M.; Edunov, S.; Baevski, A.; Fan, A.; Gross, S.; Ng, N.; Grangier, D.; Auli, M. Fairseq: A fast, extensible toolkit for sequence modeling. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Demonstrations), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Kim, M.; Park, D.; Shin, J. Learning from noisy labels with deep neural networks: A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.08199. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.08199 (accessed on 7 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, K.; Berthelot, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Carlini, N.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C. FixMatch: Simplifying semi-supervised learning with consistency and confidence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.07685. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.07685 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

| No. | Original Person Name | LLM Answer (IPA Transcription) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bill Michael | /bɪl ˈmaɪkəl/ |

| 2 | Michael Krüger | /ˈmɪçaˌeːl ˈkʁyːɡɐ / |

| 3 | Florence Ballard | /ˈflɔːrəns ˈbælərd/ |

| 4 | Brendan Gilligan | /ˈbrɛn.dən ˈɡɪ.lɪ.ɡən/ |

| 5 | Mariah Carey | /məˈraɪ.ə ˈkɛɹ.i/ |

| 6 | Valerie Trierweiler | /va.le.ʁi tʁi.ɛʁ.vaj.lɛʁ/ |

| 7 | Sergio Mattarella | /ˈsɛrdʒo mattaˈrɛlla/ |

| 8 | Donald Tusk | /ˈdɔnalt tʊsk/ |

| 9 | Laurent’as Fabiusas | /lɐu̯ˈrʲɛn.tɐs ˈfɐ.bʲu.sɐs/ |

| 10 | Ralphas Fiennesas | /ˈral.fɐs ˈfʲɛn.nɛ.sɐs/ |

| No. | Pattern, Occurrences | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrew Osagie (Didžioji Britanija),1 | Unintended match: person (location) |

| 2 | Žygimantas Augustas (Vytautas Rumšas),1 | Unintended match: person (actor) |

| 3 | Žygimantas Šeštokas (Utenos Juventus), 1 | Unintended match: person (sports team) |

| 4 | Andrius Bernotas (Tikėjimo Žodis), 1 | Unintended match: person (church) |

| 5 | Butano Karalystėje (Pietų Azija), 1 | Unintended match: location (location) |

| 6 | Baracko Obamos (Barako Obamos), 358 | Original first |

| 7 | Barakas Obama (Barack Obama), 590 | Role inversion, transcription first |

| 8 | Bušas Džordžas (George Bush), 1 | Word order inversion |

| 9 | Alicios Silverstone (Ališijos Silverstoun), 1 | Adaptation of original by fusion |

| 10 | Alastairis Bruce’as (Alisteris Briusas), 2 | Adaptation by concatenation |

| 11 | Čarlzą Darviną (Charles Darwin), 3 | Transcription in accusative |

| 12 | Čarlzas Darvinas (Charles Darwin), 9 | Transcription in nominative |

| 13 | Čarlzo Darvino (Charles Darwin), 10 | Transcription in genitive |

| 14 | Čarlzui Darvinui (Charles Darwin), 1 | Transcription in dative |

| 15 | Aleksiui Ciprui (Alexis Tsipras), 13 | Original in nominative, transcription in dative |

| 16 | Alberto Alonso (Albertas Alonsas), 1 | Non-inflected original, transcription in nominative |

| 17 | Caitlin Cahow (Keitlin Kahou), 2 | Transcription variation |

| 18 | Caitlin Cahow (Keitlin Kehou), 1 | Transcription variation |

| 19 | Caitlin Cahow (Ketlin Kahau), 2 | Transcription variation |

| 20 | Aleksis Cipras (Alexis Tspiras), 1 | Spelling error in original |

| 21 | Alavanei Ouatarai (Alassane Ouattara), 1 | Spelling errors in transcription |

| Raw Pattern, Occurrences | Operations Performed | Normalized Pattern, Occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| Alicia Keyes (Alicija Kis), 2 | Alignment failure, deleted | |

| Alicia Keys (Ališa Kis), 2 | Alicia Keys (Ališa Kis), 2 | |

| Alicia Keys (Ališija Kis), 8 | Alicia Keys (Ališija Kis), 8 | |

| Alicia Keys (Ališija Kys), 5 | Alicia Keys (Ališija Kys), 7 | |

| Ališija Kys (Alicia Keys), 2 | Role inverted, merged with preceding pattern | |

| Alicijos Kys (Alicia Keys),1 | Role inverted, genitive to nominative | Alicia Keys (Alicija Kys), 1 |

| Alisa Kis (Alicia Keys), 1 | Role inverted | Alicia Keys (Alisa Kis), 1 |

| Ališa Kys (Alicia Keys), 1 | Role inverted | Alicia Keys (Ališa Kys), 1 |

| Alisija Kis (Alicia Keys), 1 | Role inverted | Alicia Keys (Alisija Kis), 1 |

| Alisija Kys (Alicia Keys), 1 | Role inverted | Alicia Keys (Alisija Kys), 1 |

| Original | Kept Transcriptions | Discarded Transcriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Alicia | Ališija (15), Ališa (3), Alisija (2), | Alicija (1), Alisa (1) |

| Andrew | Endrius (238), Endriu (122) | Andriu (4), Andru (2), Andrevas (1), Andrju (1), Andrėjus (1) |

| Charles | Čarlzas (217), Šarlis (69), Čarlis (11), Čarlz (5) | Čarlesas (2), Čarlsas (1), Carlzas (1), |

| Marie | Mari (99), Meri (22), Marija (15), Merė (2) | Mary (1) |

| Michael | Maiklas (647), Michaelis (129), Mišelis (10), Mikaelis (7), Michaelas (6) | Michaela (1), Michailas (1), Michalas (1), Michelis (1) |

| Data Set | Description | Training Instances | Unique Instances | Oracle WER (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data | Word pairs | 133,254 | 68,167 | |

| W1 | Single-word dataset: individual mappings of O1 → T1, O2 → T2 | 239,143 | 52,167 | 7.09 |

| W2 | Word-pair dataset: O1 O2 → T1 T2 | 118,149 | 51,429 | 5.39 |

| W2+R2 | W2 augmented with reversed pairs: O2 O1 → T2 T1 | 236,216 | 102,568 | 5.43 |

| W2+R2+W1 | W2+R2 further augmented with W1 | 472,432 | 152,979 | 6.29 |

| Task | Model | Best Hyperparameters | WER, % | WER-s, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | WFST | n = 7 | 40.19 | 24.08 |

| Encoder–decoder | BS = 1024, DOUT = 0.3 | 26.87 ± 0.43 | 21.56 ± 0.35 | |

| Transformer | BS = 1024, DOUT = 0.3 | 25.49 ± 0.25 | 19.81 ± 0.22 | |

| W2 | WFST | n = 8 | 23.67 | 16.91 |

| Encoder–decoder | BS = 1024, DOUT = 0.3 | 20.22 ± 0.4 | 16.38 ± 0.24 | |

| Transformer | BS = 256, DOUT = 0.3 | 19.98 ± 0.19 | 16.19 ± 0.14 | |

| W2+R2 | WFST | n = 9 | 24.29 | 17.97 |

| Encoder–decoder | BS = 1024, DOUT = 0.3 | 19.81 ± 0.25 | 15.67 ± 0.24 | |

| Transformer | BS = 256, DOUT = 0.3 | 19.04 ± 0.18 | 15.66 ± 0.12 | |

| W2+R2+ | WFST | n = 9 | 24.55 | 18.13 |

| W1 | Encoder–decoder | BS = 1024, DOUT = 0.3 | 19.91 ± 0.27 | 16.27 ± 0.3 |

| Transformer | BS = 1024, DOUT = 0.1 | 19.30 ± 0.17 | 16.16 ± 0.17 |

| Error Category | Description |

|---|---|

| No error (0) | No mismatch. |

| Small (s) | Minor, likely imperceptible differences, such as stress-type changes affecting vowel length (e.g., Bãzas vs. Bàzas for “Buzz”), or substitution of similar vowels (e.g., Frỹdman vs. Frỹdmen for “Friedman”). |

| Medium (m) | Noticeable differences, such as incorrect stress placement (e.g., Solečìto vs. Solèčito for “Sollecito”) or mild pronunciation shifts (e.g., Òpra vs. Òupra for “Oprah”). |

| Large (l) | Prominent mismatches involving consonants, accented vowels, or the insertion/deletion/substitution of key phonetic elements (e.g., Marìja vs. Merãja, Sáid vs. Sìd, Kárl vs. Kárlos, Minãj vs. Minãž for “Mariah,” “Syd,” “Carlos,” and “Minaj,” respectively). |

| Prediction Mismatch | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | s | m | l | ||

| 0 | 24 | 141 | 33 | 311 | |

| Reference | s | 105 | 84 | 39 | 40 |

| Mismatch | m | 25 | 21 | 127 | 26 |

| l | 13 | 18 | 6 | 90 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raškinis, G.; Amilevičius, D.; Kalinauskaitė, D.; Mickus, A.; Vitkutė-Adžgauskienė, D.; Čenys, A.; Krilavičius, T. A Semi-Automatic Framework for Practical Transcription of Foreign Person Names in Lithuanian. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2107. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13132107

Raškinis G, Amilevičius D, Kalinauskaitė D, Mickus A, Vitkutė-Adžgauskienė D, Čenys A, Krilavičius T. A Semi-Automatic Framework for Practical Transcription of Foreign Person Names in Lithuanian. Mathematics. 2025; 13(13):2107. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13132107

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaškinis, Gailius, Darius Amilevičius, Danguolė Kalinauskaitė, Artūras Mickus, Daiva Vitkutė-Adžgauskienė, Antanas Čenys, and Tomas Krilavičius. 2025. "A Semi-Automatic Framework for Practical Transcription of Foreign Person Names in Lithuanian" Mathematics 13, no. 13: 2107. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13132107

APA StyleRaškinis, G., Amilevičius, D., Kalinauskaitė, D., Mickus, A., Vitkutė-Adžgauskienė, D., Čenys, A., & Krilavičius, T. (2025). A Semi-Automatic Framework for Practical Transcription of Foreign Person Names in Lithuanian. Mathematics, 13(13), 2107. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13132107