Enhanced Small Reflections Sparse-Spike Seismic Inversion with Iterative Hybrid Thresholding Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Iterative Hybrid Thresholding Algorithm

- At the kth iteration, calculateGT is the transpose of G.

- Solve the sub-problem to find the locations of optimal non-zero elements:where w(i) is the ith elements of w, is the Hadamard product of two vectors, and w is an auxiliary variable to represent the locations of non-zero elements of r. From Equation (5), the locations of non-zero elements of its solution are optimal from the view of non-increase of residue.

- Let wk is solution of Equation (5), and set,

2.2. Objective Function of Seismic Inversion

2.3. IHyTA to Solve Sparse-Spike Seismic Inversion

- At the kth iteration, calculate

- Calculatewhere,Here, ai,j is the element of A at ith row and jth column.

- Calculate wk with MISTA, i.e., Equation (11). But now, t is the largest eigenvalue of .

- Apply the hard thresholding operator to to obtain the updated r, i.e., Equation (13). But now, h is the largest eigenvalue of .

- The pseudo code is given in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. The pseudo code to obtain a new rk. |

| . (1) for i < m (m is the length of vector uk, vkand rk) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) else (7) (8) end for (9) (10) for i < m (11) (12) (13) else (14) end for |

3. Applications

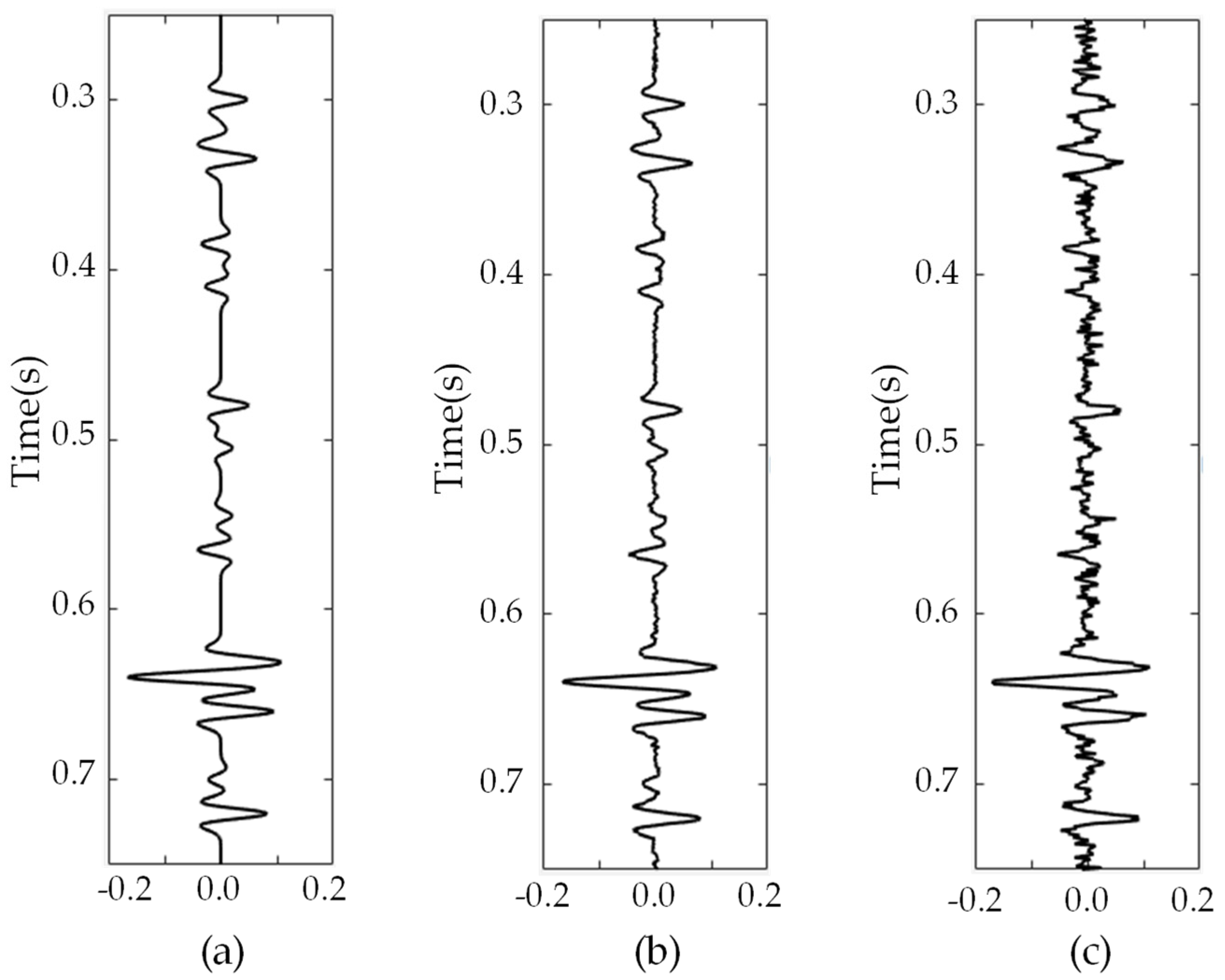

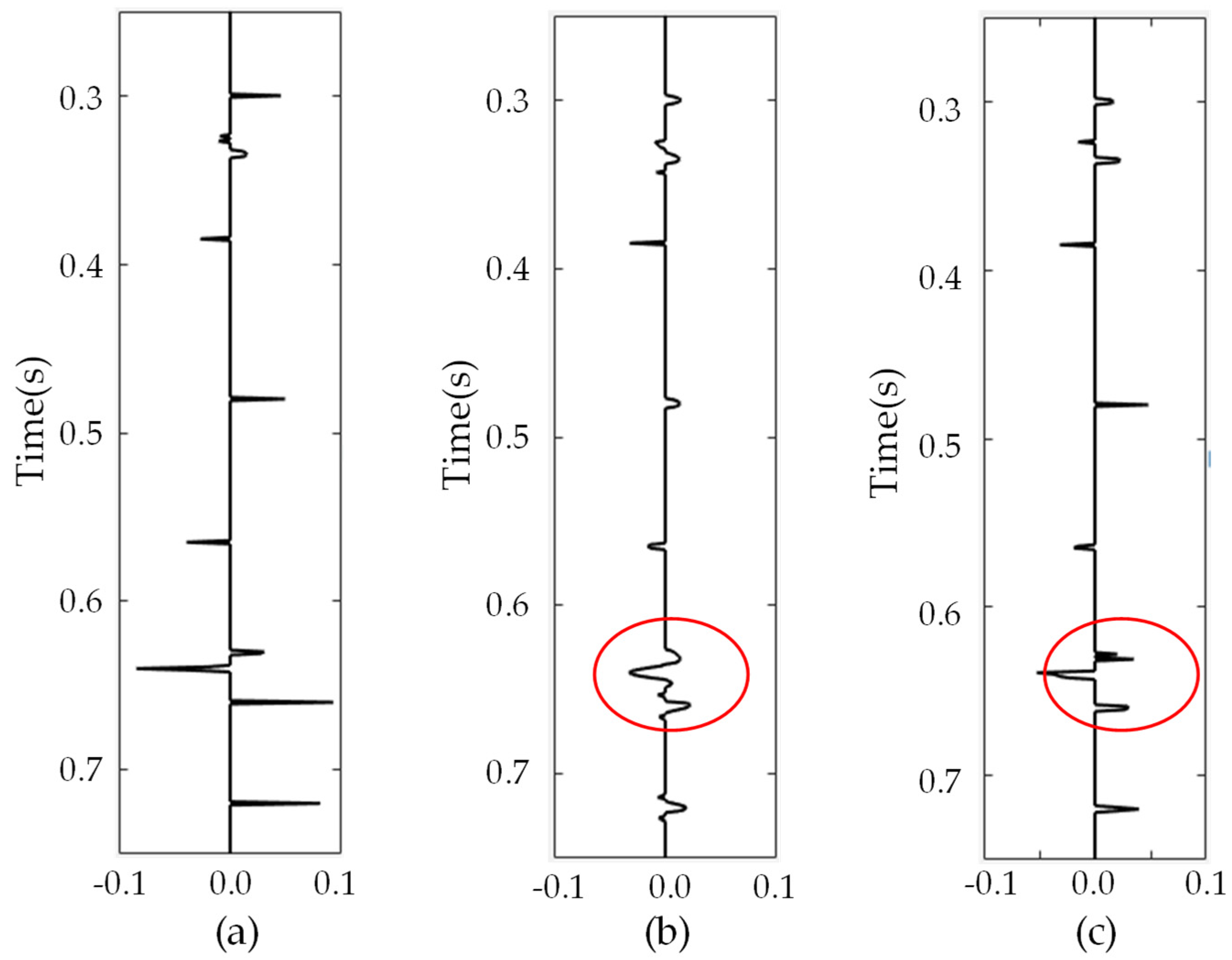

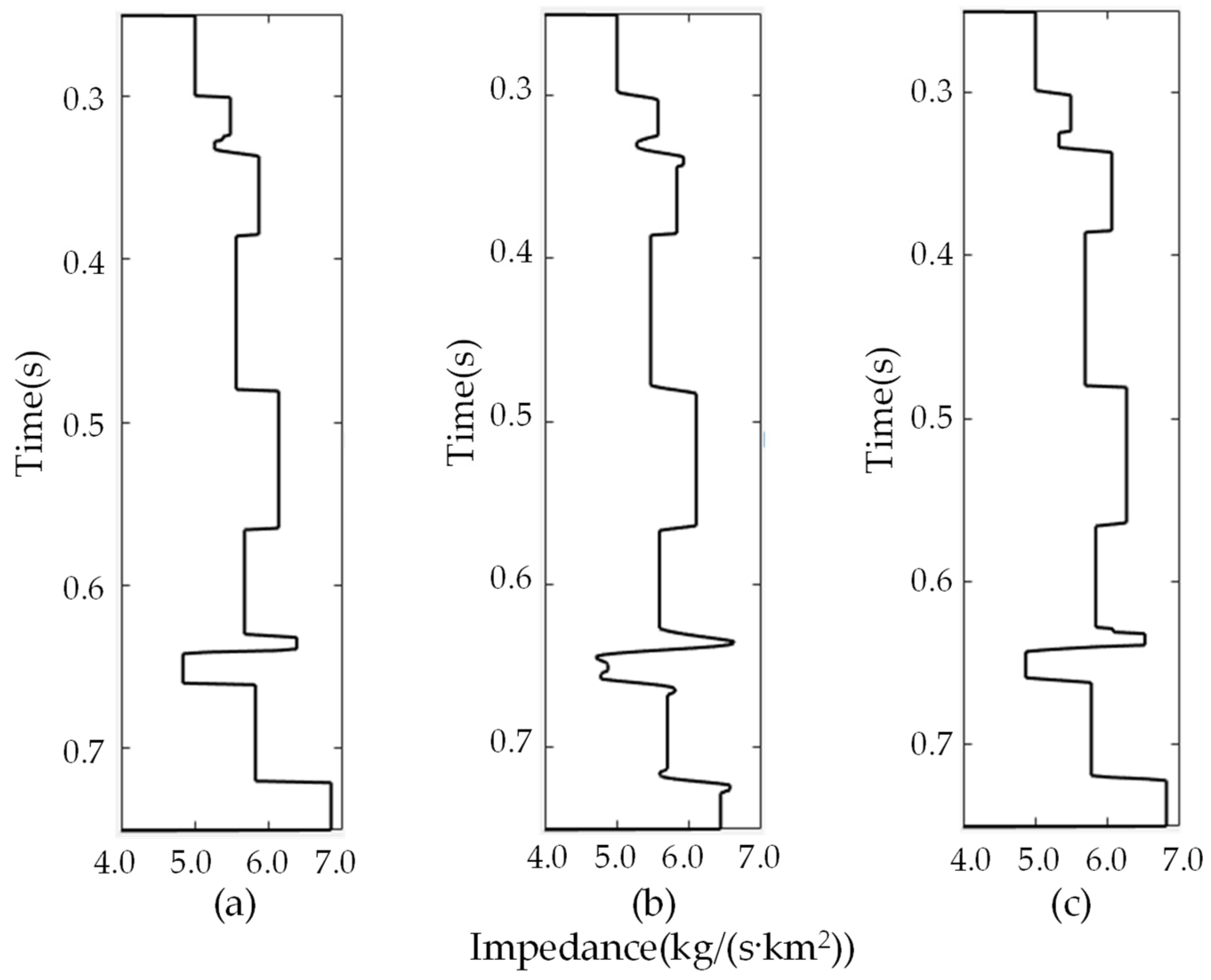

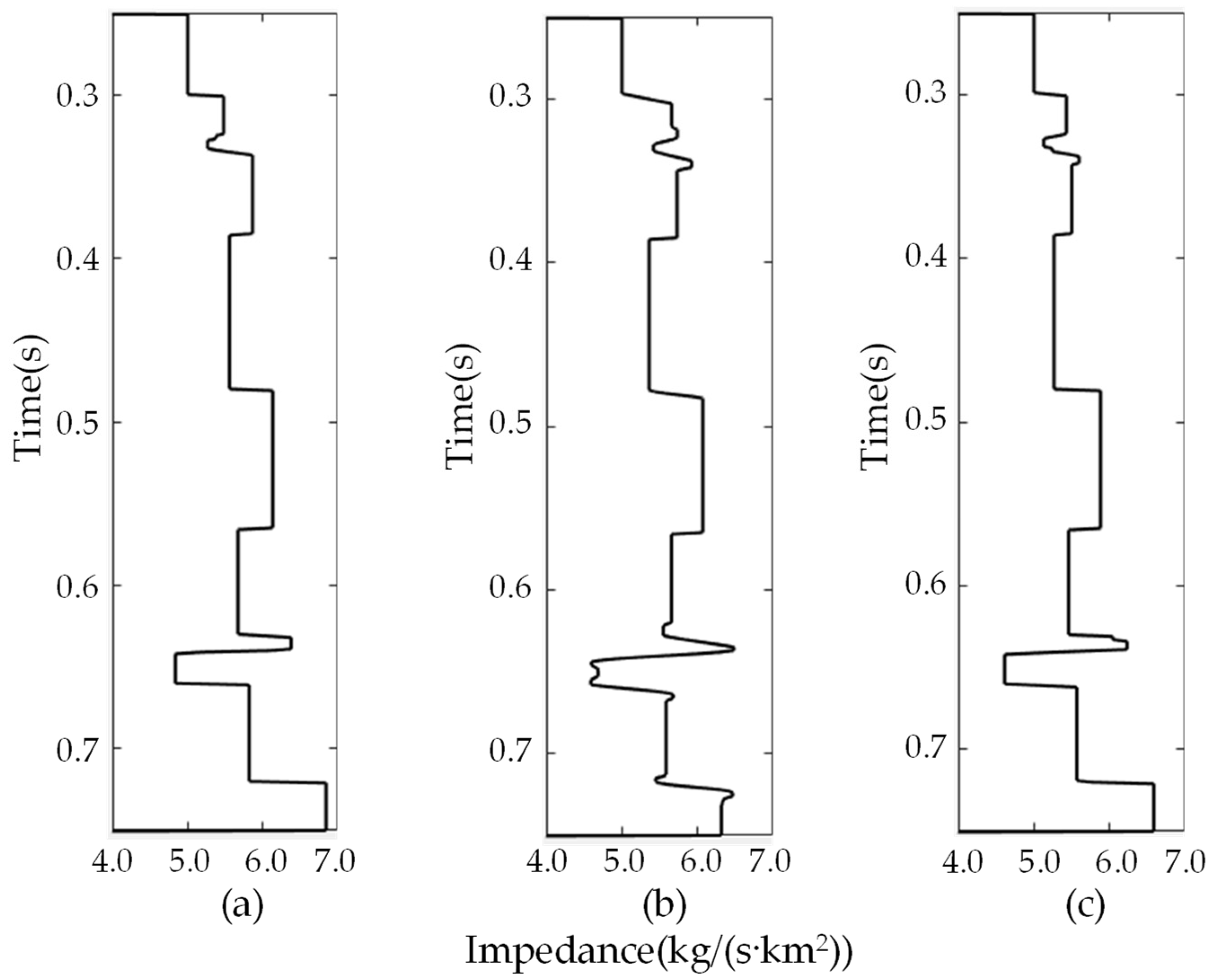

3.1. Synthetic Seismic Data Tests

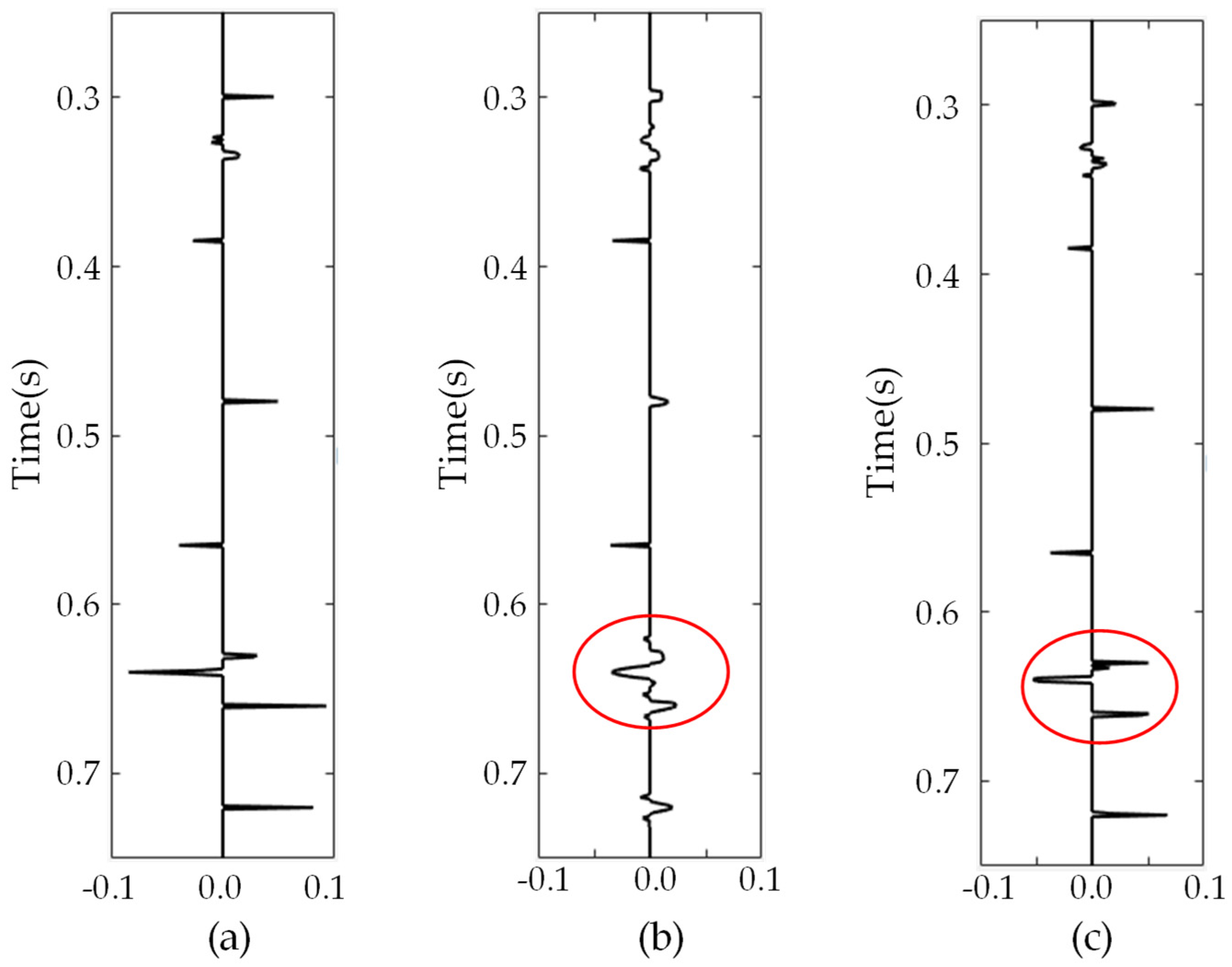

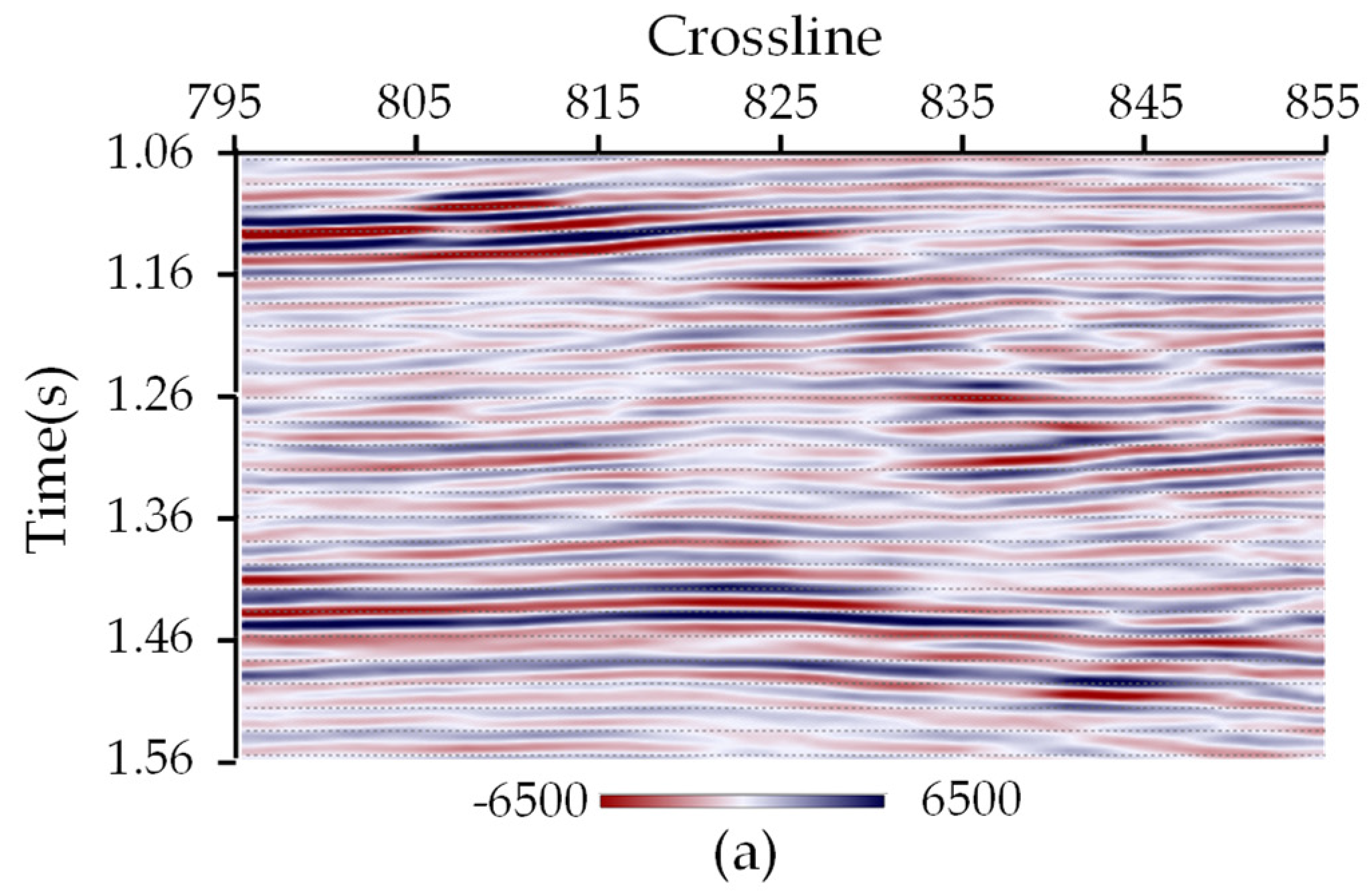

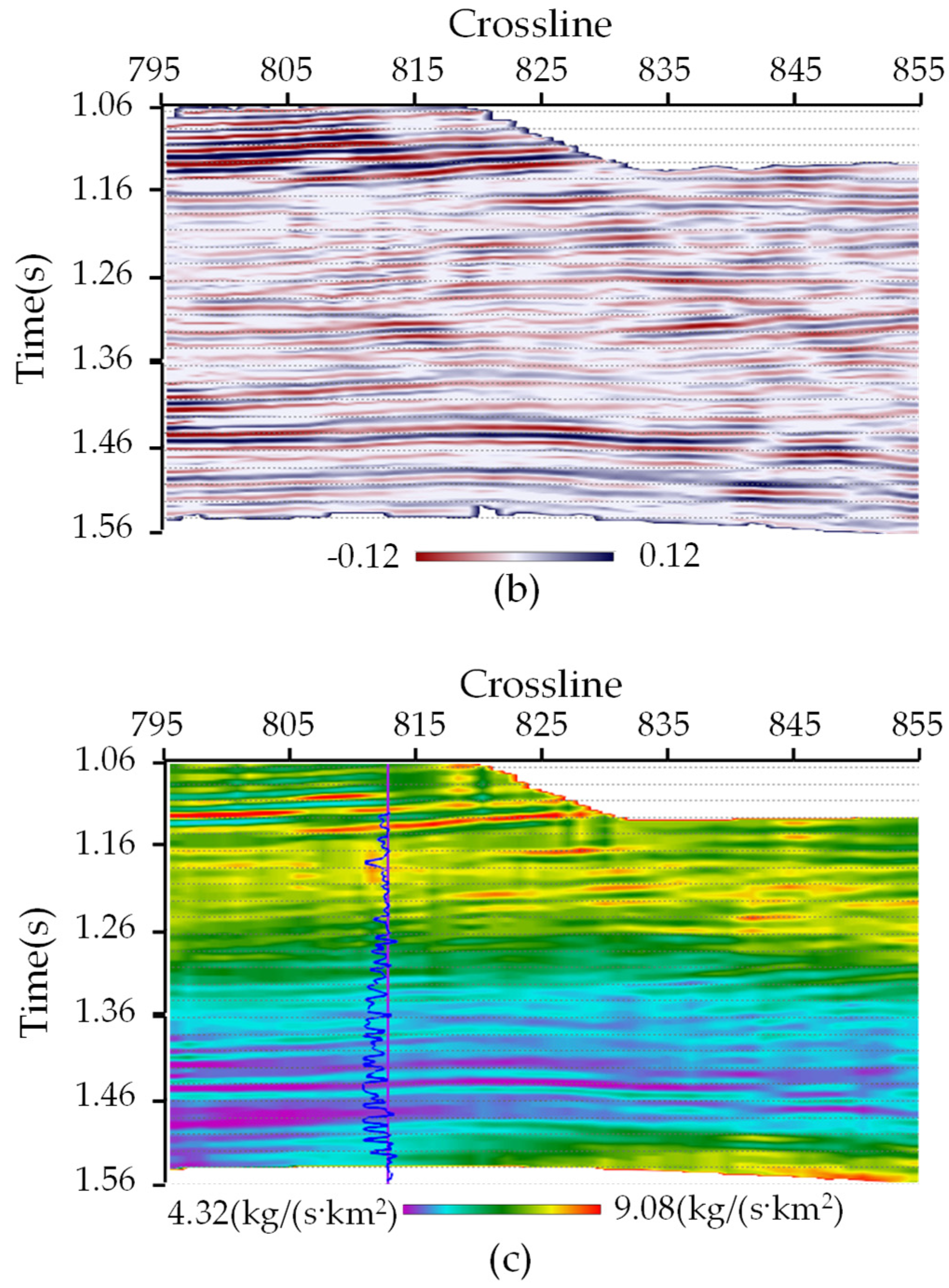

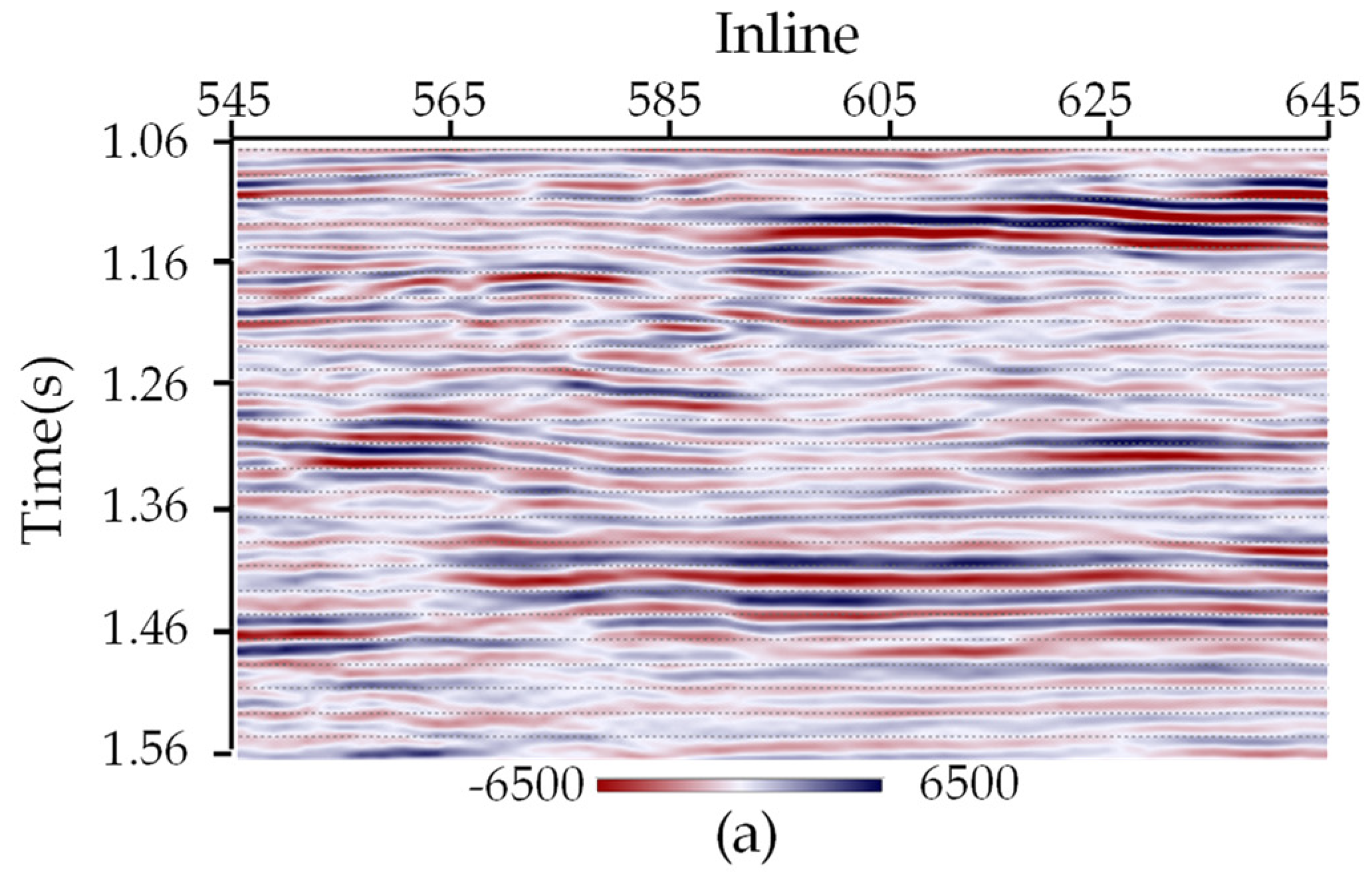

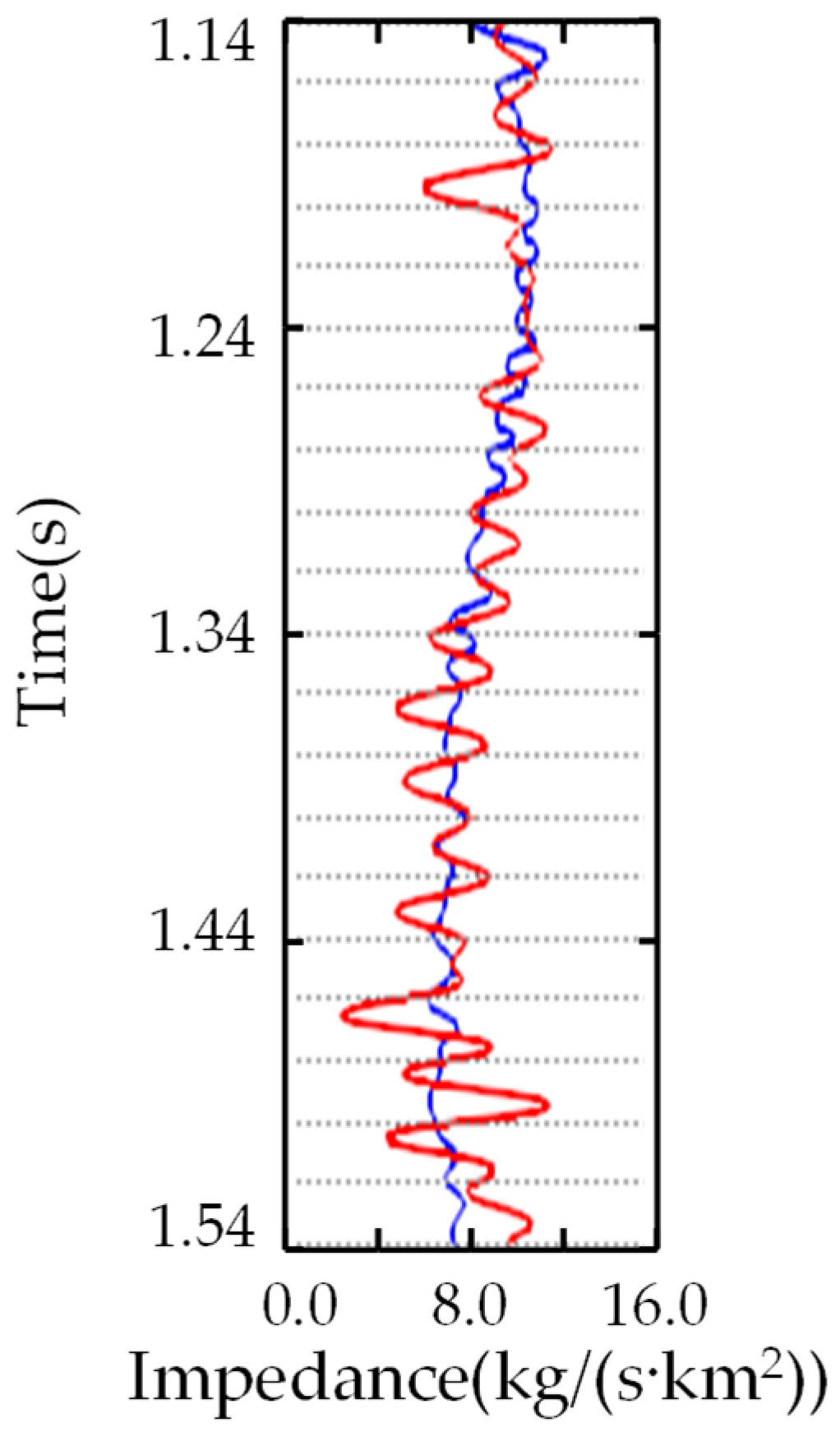

3.2. Real Seismic Data Applications

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Q.; Huang, W.; Qiao, B. Integrated seismic prediction techniques research on sandstone-type uranium deposit: A case study of uranium deposit in Qiharigetu depression. Prog. Geophys. 2018, 33, 2002–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Dai, R.; Liu, H. Seismic inversion based on L1-norm misfit function and total variation regularization. J. Appl. Geophys. 2014, 109, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Seismic Inversion: Theory and Applications; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Niu, W.; Wang, X.; Sacchi, M.D.; Chen, W.; Wang, C. Improving vertical resolution of vintage seismic data by a weakly supervised method based on cycle generative adversarial network. Geophysics 2023, 88, V445–V458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaut, R.A.; Hnetynkova, I.; Mead, J. Regularization parameter estimation for large-scale Tikhonov regularization using a priori information. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2010, 54, 3430–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tarantola, A. Inverse Problem Theory and Methods for Model Parameter Estimation; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 101–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchot, J.L. A generalized class of hard thresholding algorithms for sparse signal recovery. In Approximation Theory XIV: San Antonio 2013, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Approximation Theory, San Antonio, TX, USA, 7–10 April 2013; Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics; Fasshauer, G., Schumaker, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 83, pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, L. 2D Normalized Iterative Hard Thresholding Algorithm for Fast Compressive Radar Imaging. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosaei, H.; Hladik, M. Sparse solution of least-squares twin multi-class support vector machine using l0 and lp-norm for classification and feature selection. Neural Netw. 2023, 166, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D.; Bi, G.; Zhang, B.; Hong, W.; Wu, Y. An improved iterative thresholding algorithm for L1-norm regularization based sparse SAR imaging. Sci. China 2020, 63, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candes, E.J.; Wakin, M.B.; Boyd, S.P. Enhancing sparsity by reweighted ℓ1 minimization. J. Fourier Anal. Appl. 2008, 14, 877–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemie, W.; Sacchi, M.D. High-resolution three-term AVO inversion by means of a Trivariate Cauchy probability distribution. Geophysics 2011, 76, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Zhang, F.; Liu, H. Seismic inversion based on proximal objective function optimization algorithm. Geophysics 2016, 81, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, M.D. Reweighting strategies in seismic deconvolution. Geophys. J. Int. 1997, 129, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Dai, R. Nonlinear inversion of pre-stack seismic data using variable metric method. J. Appl. Geophys. 2016, 129, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravkin, A.; Friedlander, M.P.; Herrmann, F.J.; Leeuwen, T.V. Robust inversion, dimensionality reduction, and randomized sampling. Math. Program. 2012, 134, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F. Amplitude-versus-angle inversion based on the L1-norm-based likelihood function and the total variation regularization constraint. Geophysics 2017, 82, R173–R182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Yang, J. An alternative method based on region fusion to solve L0-norm constrained sparse seismic inversion. Explor. Geophys. 2021, 52, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F. Hard thresholding pursuit: An algorithm for compressive sensing. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2011, 49, 2543–2563. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Optimal k-thresholding algorithms for sparse optimization problems. SIAM J. Optim. 2020, 30, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, S.; Gondzio, J.; Zanetti, F.; Slowinski, R.; Artalejo, J.; Billaut, J.; Dyson, R.; Peccati, L. A regularized interior point method for sparse optimal transport on graphs. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 319, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Du, S. An effective smoothing Newton projection algorithm for finding sparse solutions to NP-hard tensor complementarity problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 451, 116074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutrouvelis, A.I.; Hendriks, R.C.; Heusdens, R.; Jensen, J.R. A Convex Approximation of the Relaxed Binaural Beamforming Optimization Problem. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 27, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Yin, X.; Zhang, F.; Kong, Q. A study on the method of joint inversion of multiscale seismic data. Chin. J. Geophys. 2009, 52, 1059–1067. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Time-Frequency Analysis of Seismic Signals; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nesterov, Y. Basis Course. In Introductory Lectures on Convex Optimization; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Q. On the momentum term in gradient descent learning algorithms. Neural Netw. 1999, 12, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

| Inversion Method | RE (5% Random Noise) | RE (20% Random Noise) |

|---|---|---|

| IHyTA | 0.0599 | 0.0829 |

| IHTA | 0.1025 | 0.1276 |

| Inversion Method | CC (5% Random Noise) | CC (20% Random Noise) |

|---|---|---|

| IHyTA | 0.9551 | 0.8879 |

| IHTA | 0.8212 | 0.7553 |

| Inversion Method | Times (ms) |

|---|---|

| IHyTA | 311 |

| IHTA | 165 |

| FIHTA | 62 |

| OTA | 1788 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Dai, R.; Fan, Z. Enhanced Small Reflections Sparse-Spike Seismic Inversion with Iterative Hybrid Thresholding Algorithm. Mathematics 2025, 13, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13010037

Feng Y, Dai R, Fan Z. Enhanced Small Reflections Sparse-Spike Seismic Inversion with Iterative Hybrid Thresholding Algorithm. Mathematics. 2025; 13(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yue, Ronghuo Dai, and Zidan Fan. 2025. "Enhanced Small Reflections Sparse-Spike Seismic Inversion with Iterative Hybrid Thresholding Algorithm" Mathematics 13, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13010037

APA StyleFeng, Y., Dai, R., & Fan, Z. (2025). Enhanced Small Reflections Sparse-Spike Seismic Inversion with Iterative Hybrid Thresholding Algorithm. Mathematics, 13(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13010037