Abstract

This paper investigates the transmission of educational attainment from parents to offspring as a mediator of intergenerational class mobility in Europe. The study covers the last two decades with data drawn from a cross-national large-scale sample survey, namely the European Social Survey (ESS), for the years 2002–2018. Interest has focused on the question of the persistence of inequality of educational opportunities by examining the attainment of nominal levels of education and the association between the educational attainment of the parent with the highest level of education and their descendants. The study also covers new trends in social mobility that consider education as a “positional good”, and a novel method of incorporating educational expansion into the transition probabilities is proposed, providing answers to whether the rising accessibility of educational qualifications attenuates the association between social origin and educational attainment. Therefore, the concept of positionality is taken into account in the estimation of intergenerational transition probabilities, and to complement the analysis, mobility measures are provided for both methods, nominal and positional. The proposed positional method is validated through a correlation analysis between the upward mobility scores (nominal and positional) with the Education Expansion Index (EEI) for the respective years. The upward mobility scores estimated via the positional method are more highly correlated with the EEI for all years, indicating a better alignment with the broader trends in educational participation and achievement.

MSC:

60J20; 60G35; 62-07

1. Introduction

Intergenerational mobility encapsulates societal transitions spanning generations and diverse socio-economic strata. It delineates individuals’ progressions and achievements in comparison to the family’s social, occupational, educational, and economic heritage, serving as a gauge for evaluating social justice and equal opportunities. Education stands as a pivotal factor in measuring social mobility and is key in curbing the perpetuation of disparities through the generations and acting as a mediator between socio-economic classes. The literature has substantiated the prominence of education in understanding and quantifying intergenerational mobility. Education is considered a significant factor due to its enduring impact on subsequent generations, in contrast to income or occupation, which can be more transient [1]. Moreover, the consistent data collection on education in various studies enables a more comprehensive analysis of intergenerational mobility. The association of education with concepts of social justice and equal opportunity further amplifies its significance in societal structures [2]. Many years of research on class mobility [3,4,5] and intergenerational mobility in relation to other indicators [6,7] have demonstrated that a major moderator of the relationship between origin and destination classes is educational achievement. Notably, studies such as those by Breen and Goldthorpe [8] and Blanden et al. [9] examine the persistent influence of education across generations and its role in shaping social mobility. Such studies emphasise the importance of education in understanding and measuring intergenerational mobility or even the function of academic establishments in influencing the movement of generations [10,11]. Moreover, Blanden et al. [9] draw attention to the relationship between education and social mobility, highlighting the enduring impact of educational opportunities on upward mobility, while Corak [12] explores intergenerational mobility from a multidimensional perspective, acknowledging the significance of education among other factors. Cunha and Heckman [13] examine the intergenerational transmission of both cognitive and noncognitive skills, illustrating how education acts as a channel for their transfer across generations. Blanden and Machin [14] investigate the relationship between education and intergenerational mobility, discussing the role of education in either facilitating or impeding social mobility. Moreover, Symeonaki and Stamatopoulou [15], Symeonaki et al. [16], Stamatopoulou et al. [17], and Stamatopoulou and Symeonaki [18] estimate intergenerational educational mobility across European countries, allowing for a comparative study of discrepancies among countries in social mobility, leveraging diverse large-scale European databases, while Symeonaki and Tsinaslanidou [19] studied intergenerational educational mobility across countries with different welfare regimes.

In most studies concerning intergenerational educational mobility, the focal point has long been on the relationship between individuals’ social backgrounds and their educational achievements, estimating intergenerational educational mobility in absolute terms, i.e., measuring education with the same nominal categories across all cohorts (e.g., using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) levels and distinguishing categories of low (ISCED levels 0–2), medium (ISCED levels 3–4), and high (ISCED levels 5–8) for both parents and offsprings), with the following outcomes indicating a diminishing influence of social backgrounds on educational achievement across multiple nations [18,20,21]. However, Goldthorpe [22] raises a pertinent question regarding the extent to which the observation of a diminishing impact of social origins, as inferred from nominal categories of educational qualifications, truly signifies a reduction in class disparities within education. He posits that in societies where education is esteemed as a positional good, individuals strive to outperform their peers in the pursuit of higher relative educational attainment. The notion of positionality revolves around the concept that the value of educational credentials is partly attributed to their relative scarcity within the population, a concept originating from Hirsch [23]. With fiercer competition for educational achievement, the influence of resources available to affluent and educated social strata becomes more pronounced. Consequently, disparities in educational attainment between social strata may persist even if the inequality of educational opportunities has ostensibly declined in nominal terms. In essence, whether education is perceived as a positional (relative) or nominal (absolute) good holds significant ramifications for understanding temporal trends in inequality in educational opportunity. Recent studies have examined intergenerational educational mobility, considering education as a positional good that captures the effect of educational expansion. Rotman et al. [24] present evidence suggesting divergent conclusions in Israel regarding trends in educational stratification between relative and absolute measures. The analysis of nominal education and years of schooling suggests consistent or decreased educational inequality, while positional measures show an increase in educational disparity. Fujihara and Ishida’s [25] research in Japan reveals differing trends in educational inequality based on whether education is measured in relative or absolute terms. Using absolute measures, they note a reduced disparity between respondents with fathers of different educational levels. However, with relative measures, they observe a widening gap between respondents from distinct paternal education backgrounds. Both studies consider position in the educational distribution or economic returns for their assessments. Triventi et al. [26] present a consistent trend of declining educational inequality in Italy, irrespective of the measurement—absolute or relative—used for education. Unlike studies in Britain, Israel, and Japan, their findings indicate a consistent decrease in educational disparity over time. While their measures of relative education differ from those of other studies, the overarching theme of assessing education in relative terms sparks inquiry into the differing trends among these countries. Moreover, Di Stasio et al. [27] analyse education as a positional good, contrasting country contexts to identify where education holds positional value. They find that strong vocational systems relate to lower overeducation instances, suggesting reduced positional value in these settings. Their study categorises countries based on overeducation and its returns, connecting these groupings to various models of the education–occupation relationship.

The present study aims to investigate both nominal (absolute) and relative (positional) patterns of intergenerational educational mobility in Europe by analysing transitions across the educational levels of respondents and their parents in Europe using raw data drawn from the European Social Survey (ESS) from the year 2002 and onwards. The objective is to reveal challenges faced by particular social strata in progressing upward within the educational framework using and comparing both nominal and positional methods. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to incorporate positionality in the estimation process of the transition probabilities. To validate the proposed methodology for measuring mobility, we compare the correlations of upward probability measures, both nominal and positional, with the Educational Expansion Index (EEI) used in Araki [28]. Correlation coefficients are examined, and the positional approach is identified as superior, as it consistently exhibits higher correlations for all years.

The paper is outlined as follows. Section 2 reveals all the necessary information concerning the proposed methodology and the ESS data that are utilised in order to estimate intergenerational educational mobility in absolute and relative terms. Section 3 presents the measurement results of intergenerational educational mobility, nominal and positional, and the validation tests performed. Section 4 gives the conclusions of the study and provides the reader with a discussion concerning the comparison of absolute and positional intergenerational mobility and aspects of future work.

2. Materials and Methods

In the present analysis, data were drawn from the European Social Survey (ESS), a survey spanning over 40 countries since 2002, designed to track European public attitudes and values and furnish European social and attitudinal indicators. The data was analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 28.0. (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The present study measures nominal and positional intergenerational educational mobility in Europe, making use of 5 rounds of ESS spanning a period of over 16 years (i.e., ESS1, ESS3, ESS5, ESS7, ESS9). To ensure comparability, the work specifically includes European countries that have participated in all rounds of the ESS, i.e., Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Slovenia, and the UK. Due to the different data collection methods used in ESS10 (face-to-face interviews, self-completion questionnaire), the variable of parental education was not measured; consequently, the most recent trends of mobility are not included in this analysis. The study also aims to provide aggregated measures for these European countries.

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents per round. The realised sample sizes and basic socio-demographic characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1. As shown, most of the respondents for all the countries under investigation were women, with a mean age from 41.90 (Ireland, ESS1) to 49.14 (Portugal, ESS7) years, at least 39.03% (Ireland, ESS5) to 61.36% (Sweden, ESS3) were in a paid job, while the percentage for participants in education, as the main activity within the last seven days, ranged from 7.46% (UK, ESS1) to 15.33% (Slovenia, ESS1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, per ESS round (2002, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018).

Within the ESS, cross-national educational attainment variables for both parents and individuals were generated from country-specific variables in order to be standardised and to align with the latest International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED11). (The production of the generated harmonised educational variable is particularly dependent on the availability of sufficiently detailed country-specific education variables. For rounds ESS 5–9, the 7-category variable “es-isced” is used in the analysis for both respondents and parents. For rounds ESS 1–4, the same variable has not been produced for all parents and/or for all countries. Thus, for these rounds, we used the previous harmonised 5-category variable “edulvlva” in order to classify both respondents and parents into the educational categories). To facilitate the analysis, educational attainment was transformed into three educational categories using the transformation utilised by EUROSTAT, i.e., ISCED levels 0–2 = Low, ISCED levels 3–4 = Medium, and ISCED levels 5–8 = High. For parents, the maximum educational level was taken into consideration for the analysis, assuming that the highest educational level between parents will positively affect children’s educational attainments. Because of the lack of a harmonised variable for the highest level of education for specific counties in the datasets of ESS1 and ESS7, we do not display results for Norway (2002) and for Hungary (2014). Table 2 outlines the ISCED levels and the categorisation to three educational levels, indicated by the color shading of the cells.

Table 2.

ISCED levels and educational categories.

Data weighting was performed using analysis weight (anweight). This specific weight is suitable for all types of analysis as it corrects for differential selection probabilities within each country as specified by sample design, for nonresponse, for noncoverage, and for sampling error related to the four post-stratification variables and takes into account differences in population size across countries (https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/methodology/ess-methodology/data-processing-and-archiving/weighting, accessed on 10 November 2023).

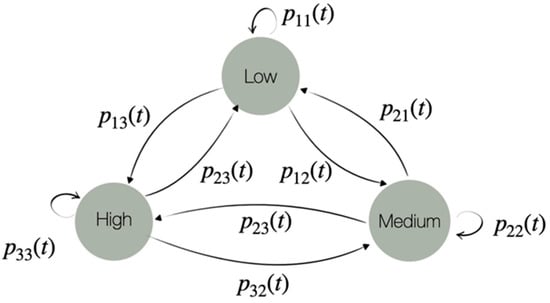

Using raw data drawn from the ESS, we first measure intergenerational educational mobility in absolute terms, using the same educational levels both for parents and offspring. We define parental education as the educational level of either the father or the mother, based on the higher educational attainment between them. We employ Markov stochastic models to quantify educational mobility across various European countries. A Markov stochastic model describes a dynamic population system that evolves over time according to probability laws [29]. The Markov property is used in the sense that each state depends only on the previous one in time. In our case, a state represents the educational level of parents and individuals at a given time . In more detail, we begin by stratifying the population into distinct categories according to their educational status. Let be the state space of the proposed closed model (in our case ), where no members enter or leave the system. For each , we estimate the transition probability matrices, the elements of which depict the transitions occurring between educational states and across generations. Each element of the matrix describes the probability of an individual to move from state (parental educational level) to state (individual’s educational level). The off-diagonal elements of the matrix signify the shifts or movements of individuals, while indicates the probability of individuals remaining static over time in relation to their parental educational status (see also [15,16]). The above model describes a closed Non-Homogeneous Markov System, since our transition probabilities are estimated for each time step . For a comprehensive description of the theoretical background of the Markov systems, see [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the proposed model.

Figure 1.

Transition diagram of the proposed closed Markov system.

Based on the transition probabilities of each transition matrix, mobility measures are estimated for the selected years of the ESS data for each country. Hence, we calculate indices for upward and downward mobility, as well as the immobility index [38,39] and the Prais–Shorrocks index [40,41]. Equations (1)–(4) give the mathematical expressions of the computed indices:

Shifting from an absolute to a relative perspective in the evaluation of educational attainment presents a notable challenge since “there is no obvious ‘one best way’ of producing a relative measure” [42]. We aim to incorporate positionality into the measurement of transition probabilities following the subsequent methodology.

The proposed method is comparable to that implemented by Triventi et al. [26] for calculating the cumulative advantage associated with each educational level. To understand how positionality has influenced educational attainment, we estimated the proportions of individuals at all educational levels using EUROSTAT’s data available for the last two decades and the classification described in Table 2. A logarithmic transformation of the proportions is equal to the Educational Competitive Advantage Score (ECAS) used in Triventi et al. [26], which “attributes to each educational level a measure of its competitive advantage on the basis of how many individuals attained at least that qualification in a given year”. Rather than employing the actual ECAS for a specific year t, we opt for using the proportions of individuals in various educational levels as weights, denoted by , , and , to maintain the stochastic properties of the transition probability matrices. Thus, the proportion of individuals with low, medium, and high education at the time of the survey is treated as a set of weights reflecting the relative prevalence or importance of each educational category in the population. The transition probabilities are then calculated by considering not only the likelihood of moving from one educational level to another but also by incorporating the prevalence of individuals in each category as a weight. The weights act as a scaling factor, influencing the contribution of each educational category to the overall transition probabilities, and serve as a normalisation assigned to each (absolute) transition probability based on the factor of competitive advantage. Thus, we applied proportional scaling to adjust the transition probabilities based on the proportions, using the following equation to estimate the positional transition probabilities :

The applied weights stem from the proportional representation of individuals within various educational tiers across distinct time frames. These adjustments accommodate the transition probabilities, ensuring alignment with the evolving educational landscape over recent years. Through these weights, the impact of current educational distributions on projected transitions is highlighted, preserving the overall structure of transition probabilities. Accounting for these educational distribution shifts can substantially refine the precision of the analysis, enabling a more accurate and positional representation of intergenerational educational mobility.

Having estimated both nominal and positional mobility rates, we undertake cluster analysis, an exploratory method that categorises cases with akin characteristics into clusters. The classification of surveyed countries utilises both nominal and positional upward mobility. Initially, the agglomerative hierarchical method determines the optimal number of clusters that best characterises the data. Subsequently, building on the outcomes of this approach, a K-means analysis is applied to classify the countries into the suggested distinct, mutually exclusive clusters.

To substantiate the proposed methodology, the upward mobility scores were subjected to correlation analysis with the Education Expansion Index (EEI) for the corresponding years, as computed using EUROSTAT’s data. The Educational Expansion Index is defined as the percentage of individuals aged between 15 and 64 that possess tertiary degrees [28] and serves as a metric encompassing the comprehensive expansion of educational attainment across a population, offering insights into alterations in educational participation and achievement. Examining the correlation between the upward mobility scores, calculated using both absolute and relational approaches, and the Educational Expansion Index (EEI) facilitates an evaluation of the extent to which the proposed measure aligns with the broader shifts in educational participation and achievement over the specified timeframe. The expectation is that the two upward mobility scores, nominal and positional, will exhibit a strong correlation. The preferred methodology would be the one generating a higher correlation coefficient between the upward mobility scores and the Education Expansion Index (EEI) for the respective years.

3. Results

3.1. Nominal/Absolute Transition Probabilities

In this section, we estimate the transition probability matrices to portray the shifts between educational categories for both parents and respondents, encapsulating the movement between the same educational stages. Table A1 in the Appendix A presents the nominal transition probability matrices for all countries and ESS rounds, as well as the respective mobility indices. From the results, it is obvious that individuals from low-educated backgrounds tend to gain better education than their parents, although they have considerably fewer chances to complete tertiary education compared to those originating from medium- or highly educated origins. Indeed, the access to tertiary education seems unequal between people from different educational backgrounds in the majority of the sample, as parents’ educational profile seems to matter in all countries. However, it is notable that the upward movements predominate over the downward mobility, while the immobility rates decrease over time.

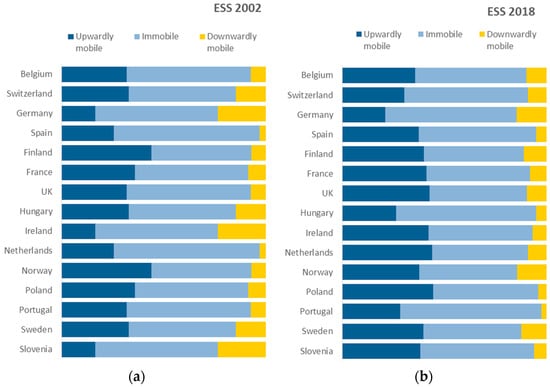

Figure 2 provides a more comprehensive overview of the transitions between educational categories, illustrating the percentages of individuals moving upward, downward, or remaining in the same educational category as their parents across all surveyed countries from 2002 to 2018. The figure reveals variations in educational flows across countries, with Finland and Belgium displaying a steady trend of upward movement through ESS. Furthermore, a noticeable increase in percentages of upwardly mobile individuals over time is detected in the majority of the countries, especially in Ireland and Slovenia, where the values of the upward mobility index rose sharply from 2002 to 2018. Some exceptions also exist, such as Switzerland and Hungary, where a decrease in the overall mobility is recorded from 2002 to 2018.

Figure 2.

The percentages of people who moved upward or downward or had the same education as their parents, by country, according to the (a) ESS1 dataset and the (b) ESS9 dataset.

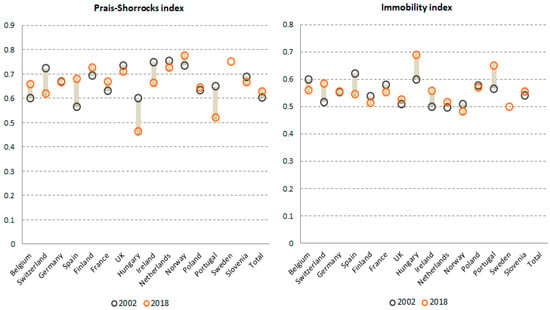

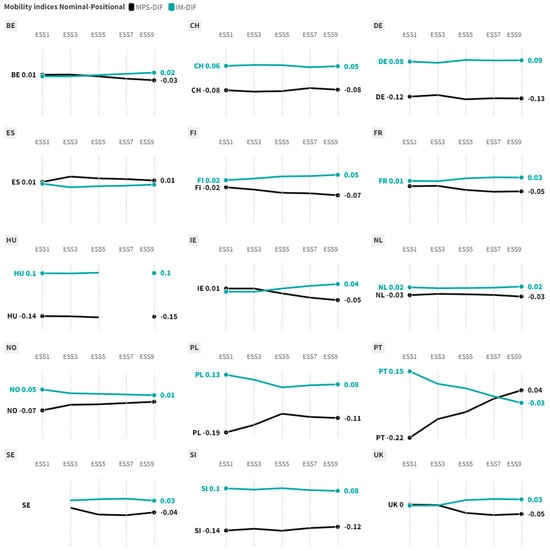

The values of both the Prais–Shorrocks and immobility indices validate the observed trend from 2002 to 2018 depicted in Figure 3, showing variations between countries and years. In particular, Norway and the Netherlands seem to be steadily the most mobile in the sample, while Hungary, Portugal and Switzerland show higher values of immobility, even though a notable decrease is indicated from 2002 to 2018.

Figure 3.

Changes in mobility rates by country: 2002 and 2018 (nominal mobility).

3.2. Education as a “Positional Good”: Estimating Positional Transition Probabilities

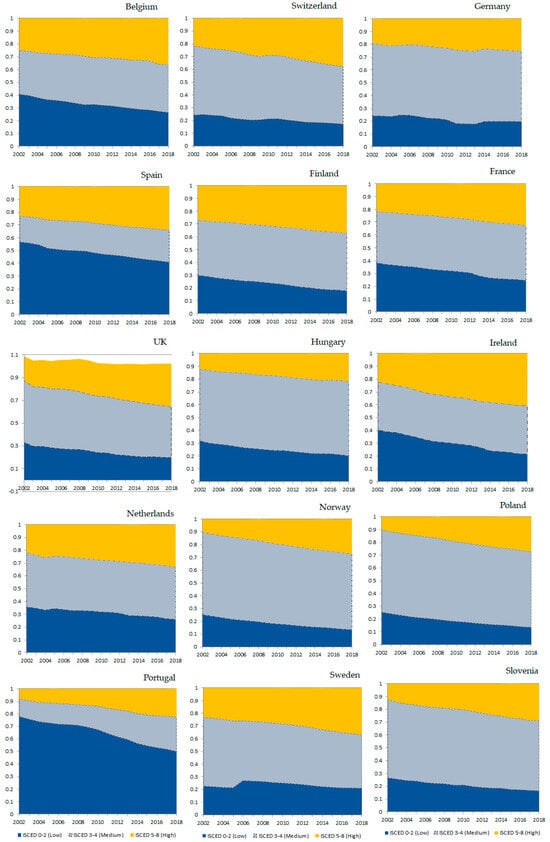

In order to estimate the positional transition probabilities, the respective weights were estimated. Figure 4 depicts the proportions of individuals belonging to the three educational levels based on the data provided by EUROSTAT with the use of the EU-Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). The depicted trend in the proportions highlights intriguing shifts in educational categories over this period (2002–2018). The proportions of low-educated individuals (ISCED 0–2) display a steady fall, which suggests a decline in the prevalence of lower educational levels over time and a diminishing number of individuals with lower educational qualifications. On the contrary, the proportions of medium-educated individuals (ISCED 3–4) exhibit relatively modest changes, suggesting stability rather than cumulative advantages. Meanwhile, the rising trend in the proportions of highly educated individuals (ISCED 5–8) implies a diminishing competitive advantage associated with higher educational levels and a decreasing prominence or influence of higher educational qualifications over the observed period.

Figure 4.

Country-wise distribution of proportions in educational attainment levels, 2002–2020 (EUROSTAT, based on the EU-LFS data).

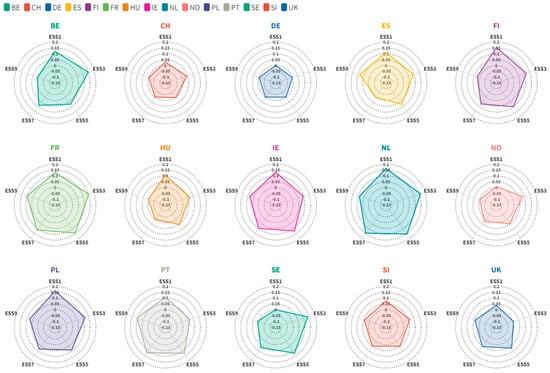

Since transition probability matrices need to maintain their stochastic property, we opted for the incorporation of proportions in the weighting scheme adhering to this principle. Using Equation (1), the respective weights presented in Figure 4, and the nominal transition probability matrices (Table A1), the positional transition probability matrices were estimated for the participating countries and years. Based on these positional transition probabilities, the upward and downward mobility indices were reconstructed and calculated in order to be compared with the nominal results. The rest of the mobility indices are estimated as aforementioned [38,39,40,41]. The respective matrices are exhibited in Table A1 in the Appendix A. In general, from the results, it is evident that concerning the transition probabilities, the relative measure of mobility is more robust than the absolute counterpart. In particular, for the majority of the countries, takes higher values in the positional matrices compared to the nominal ones, and seems to be overrated in the nominal results. Thus, shifting from a nominal to a relative perspective, people with low educational backgrounds appear to have greater chances of moving upwards and attaining a medium level of education. However, a reversed pattern is detected in Spain and Portugal. Likewise, the observed mobility appears to overestimate the chances of people from highly educated backgrounds attaining tertiary education since transition probabilities are considerably lower after the weights are applied. A noticeable example of this trend is the case of Hungary, where falls from 0.569 to 0.292 (ESS3) after the adjustment. However, Belgium and Ireland show no significant differences between nominal and positional transition matrices.

Figure A1 presents the differences in upward mobility indices before and after the adjustment. As shown, in all countries (except Germany), this difference between nominal and positional results takes positive values, which indicates that the nominal measure seems to exaggerate the upward movements compared to each relative measure. Between the countries, the Netherlands and France show greater differences when nominal and positional upward rates are compared, while the results for Switzerland, Norway and UK show no significant variations between the rates. On the other hand, smaller differences are observed for the case of the Prais–Shorrocks and immobility indices, in the comparison of nominal and positional mobility (Figure A2). This trend might be attributed to the fact that both and have been constructed based on the chances of people moving upwards or downwards in the social space and not on the actual flows, and for that reason, it better reflects the relative mobility. However, Poland, Hungary, and Slovenia seem to be exceptions to this trend, as the difference in takes significant higher values for these countries. Also, an interesting trend was detected for Portugal, where the difference in mobility rates decreased over time, reaching convergence, probably because of the changes that occurred in the participation of Portuguese in the different levels of education through the years 2002–2018 (as shown also in Figure 3).

3.3. Validation

To validate the proposed methodology, the upward mobility scores underwent correlation analysis, with the Education Expansion Index (EEI) calculated using EUROSTAT’s data for the corresponding years. Evaluating the correlation between the upward mobility scores, computed through both nominal and positional approaches, and the Educational Expansion Index (EEI) enables an assessment of the alignment of the proposed measure with broader shifts in educational participation and achievement over the specified period. Table 3 presents Pearson’s correlation coefficient between nominal and positional upward mobility, and Table 4 shows the respective correlations among nominal and positional upward mobility and EEI for the respective year. The two upward mobility indices exhibit a strong correlation, as anticipated. Notably, positional upward mobility demonstrates a higher correlation with EEI, indicating a better alignment with the broader trends in educational participation and achievement.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlations coefficients among nominal upward mobility and positional upward mobility per ESS round.

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlations coefficients among nominal upward mobility , positional upward mobility and the respective Educational Expansion Index (EEI) per ESS round.

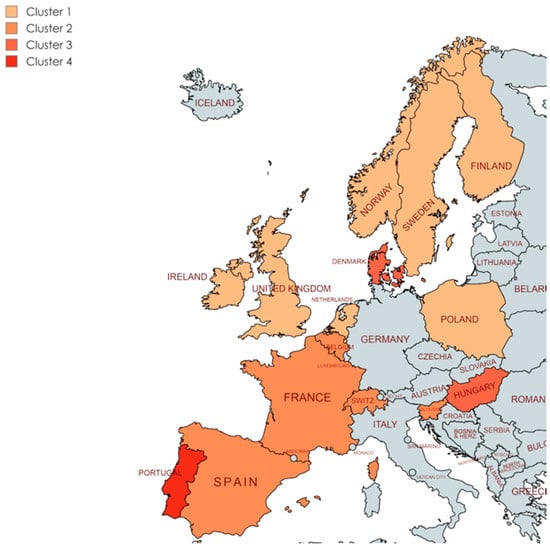

To enhance the credibility of the proposed methodology, we conducted a cluster analysis utilising both hierarchical clustering and the K-means method and using both absolute and positional upward mobility scores across countries. Presented here are the findings from the most recent ESS data. The hierarchical process identified four clusters of counties when considering both nominal and positional upward mobility rates. This aligns with the welfare regime typology observed in European countries to a great extent. Specifically, based on the latest ESS data, the resulting clusters are as follows: Cluster 1 includes Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, France, and Slovenia; Cluster 2 comprises Germany and Hungary; Cluster 3 encompasses Finland, Norway, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, and the UK; and Cluster 4 consists of Portugal, a standalone cluster, distinguished by its exceptionally low values of the variables in comparison to the others (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Clusters of countries based on nominal and positional upward mobility, ESS, 2018.

The simulation conducted for both upward positional mobility scores and absolute scores stands as a robust validation of the theoretical framework outlined in the paper. The variables used were the educational levels of the father, mother, and respondent, and the simulation spanned across the examined year, 2018. The simulation was conducted for the selected countries—Ireland, Belgium, Germany, and Portugal—which emerged as representatives of distinct clusters through prior clustering analysis. By aligning the simulated outcomes with our theoretical predictions, this comprehensive approach provides evidence of the consistency and applicability of the proposed model. The convergence of theoretical insights with simulated results in these representative countries enhances the credibility of the findings, emphasising the robustness of the approach in capturing the nuances of upward mobility dynamics.

4. Discussion

The present section interprets the presented results and provides insights into the patterns of intergenerational educational mobility, considering both nominal and positional perspectives. The aim was to examine the relationship between parental and individuals’ educational outcome in relative terms in order to better understand the influence of education across generations. In this context, the proposed methodology is based on the concept of positionality, where the educational expansion and the rising accessibility of educational qualifications are taken into account. It is assumed that this novel additional element in the measurement of mobility would produce a more reliable picture of educational inequalities. In order to explore this hypothesis, raw data were drawn from the European Social Survey for the 15 participated in all rounds of the surveyed countries to capture trends in educational transitions from 2002 to 2018.

The analysis of nominal transition probability matrices reveals distinct tendencies in educational mobility across European countries. More specifically, individuals from lower-educated backgrounds show a propensity to attain higher education than their parents, although access to tertiary education appears unequal. As upward mobility surpasses downward movements, a decline in immobility rates over time suggests a notable enhancement in educational opportunities. This trend signifies a propensity for individuals to progressively distance themselves from their parents’ educational level. Notable exceptions, such as Switzerland and Hungary, exhibit a decrease in overall mobility. The examination of specific countries, including Finland and Belgium, underscores diverse trends in upward mobility.

The novel approach of incorporating positionality in transition probabilities enhances the understanding of mobility patterns. Weighted positional matrices demonstrate the robustness of relative measures compared to absolute ones. Low-educated individuals exhibit greater chances for upward mobility, challenging conventional findings. However, Spain and Portugal deviate from this trend. Discrepancies in the likelihood of highly educated individuals attaining tertiary education emerge after adjustment, exemplified by Hungary’s notable shift.

To validate the proposed methodology, correlations between upward mobility indices and the Educational Expansion Index (EEI) were examined. The positional approach exhibits stronger alignment with broader trends in educational participation and achievement, as indicated by higher correlations with EEI for all examined ESS rounds. Differences between nominal and positional measures vary across countries, emphasising the need for a nuanced understanding of mobility patterns.

Apparently, the observed trends hold implications for policymakers and researchers. Acknowledging education as a positional good necessitates tailored policy interventions to address relative mobility. Future research should investigate the subtle dynamics driving educational shifts, considering socio-economic, cultural, and policy-related factors. Furthermore, longitudinal analyses can offer a more profound insight into the changing patterns of mobility, complementing the aforementioned findings with new results deriving from the intermediate ESS rounds (e.g., ESS round 2). The presented findings contribute to the discourse on intergenerational educational mobility, offering valuable insights for policymakers, aiming to foster equitable educational opportunities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; methodology, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; statistical analysis with IBM SPSS v.29, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; validation, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; formal analysis, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; investigation, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; data curation, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, G.S., E.T. and M.S.; visualisation, G.S. and E.T.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the European Social Survey at https://ess-search.nsd.no/en/study/bdc7c350-1029-4cb3-9d5e-53f668b8fa74, accessed on 12 November 2023.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge use of raw data from: ESS Round 1: European Social Survey Round 1 Data (2002). Data file edition 6.6. Sikt—Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS1-2002, ESS Round 3: European Social Survey Round 3 Data (2006). Data file edition 3.7. Sikt—Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway-Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS3-2006, ESS Round 5: European Social Survey Round 5 Data (2010). Data file edition 3.4. Sikt—Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS5-2010, ESS Round 7: European Social Survey Round 7 Data (2014). Data file edition 2.2. Sikt—Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS7-2014, European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC). (2023), ESS9—integrated file, edition 3.2 [Data set]. Sikt—Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.21338/ess9e03_2. The study also makes use of the EUROSTAT’s data Population by educational attainment level, sex and age (%)—main indicators: Online data code: edat_lfse_03.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Transition probabilities and mobility indices for both nominal and positional mobility by country and ESS1(2002), ESS3(2006), ESS5(2010), ESS7(2014), and ESS9(2015) rounds.

Table A1.

Transition probabilities and mobility indices for both nominal and positional mobility by country and ESS1(2002), ESS3(2006), ESS5(2010), ESS7(2014), and ESS9(2015) rounds.

| P(YEAR) | Nominal Mobility | Positional Mobility | Nominal Mobility | Positional Mobility | Nominal Mobility | Positional Mobility | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Probabilities | Transition Probabilities | Transition Probabilities | Transition Probabilities | Transition Probabilities | Transition Probabilities | |||||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | Belgium | Finland | Finland | France | France | |||||||||||||||||||

| P(2002) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.600 | 0.599 | 0.319 | 0.073 | 0.595 | 0.603 | 0.198 | 0.199 | 0.693 | 0.538 | 0.439 | 0.070 | 0.717 | 0.522 | 0.284 | 0.194 | 0.630 | 0.580 | 0.359 | 0.085 | 0.648 | 0.568 | 0.230 | 0.202 | |

| P(2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.594 | 0.604 | 0.354 | 0.071 | 0.588 | 0.608 | 0.240 | 0.152 | 0.699 | 0.534 | 0.435 | 0.080 | 0.736 | 0.509 | 0.315 | 0.176 | 0.675 | 0.550 | 0.404 | 0.077 | 0.691 | 0.540 | 0.251 | 0.210 | |

| P(2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.635 | 0.577 | 0.356 | 0.084 | 0.639 | 0.574 | 0.280 | 0.146 | 0.720 | 0.520 | 0.415 | 0.092 | 0.775 | 0.483 | 0.313 | 0.203 | 0.593 | 0.605 | 0.378 | 0.061 | 0.632 | 0.579 | 0.233 | 0.188 | |

| P(2014) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.638 | 0.574 | 0.365 | 0.093 | 0.655 | 0.564 | 0.278 | 0.158 | 0.735 | 0.510 | 0.430 | 0.100 | 0.793 | 0.471 | 0.357 | 0.172 | 0.623 | 0.584 | 0.399 | 0.074 | 0.672 | 0.552 | 0.286 | 0.162 | |

| P(2018) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.659 | 0.561 | 0.356 | 0.099 | 0685 | 0.544 | 0.346 | 0.110 | 0.727 | 0.515 | 0.399 | 0.111 | 0796 | 0.469 | 0.376 | 0.155 | 0.623 | 0.584 | 0.399 | 0.074 | 0.716 | 0.523 | 0.308 | 0.010 | |

| Germany | Germany | Hungary | Hungary | Ireland | Ireland | |||||||||||||||||||

| P(2002) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.669 | 0.554 | 0.165 | 0.233 | 0.787 | 0.475 | 0.234 | 0.291 | 0.602 | 0.599 | 0.312 | 0.088 | 0.746 | 0.502 | 0.205 | 0.293 | 0.749 | 0.501 | 0.408 | 0.066 | 0.738 | 0.508 | 0.276 | 0.216 | |

| P(2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.669 | 0.554 | 0.195 | 0.201 | 0.778 | 0.482 | 0.245 | 0.273 | 0.603 | 0.598 | 0.294 | 0.101 | 0.748 | 0.502 | 0.226 | 0.272 | 0.743 | 0.505 | 0.447 | 0.062 | 0.732 | 0.512 | 0.349 | 0.139 | |

| P(2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.624 | 0.584 | 0.219 | 0.120 | 0.757 | 0.496 | 0.275 | 0.229 | 0.601 | 0.599 | 0.305 | 0.082 | 0.752 | 0.499 | 0.249 | 0.252 | 0.631 | 0.580 | 0.415 | 0.045 | 0.647 | 0.569 | 0.291 | 0.140 | |

| P(2014) | NA | NA | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.701 | 0.533 | 0.200 | 0.158 | 0.828 | 0.448 | 0.283 | 0.269 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.598 | 0.601 | 0.428 | 0.045 | 0.638 | 0.575 | 0.331 | 0.094 | |

| P(2018) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.666 | 0.556 | 0.211 | 0.145 | 0.794 | 0.470 | 0.287 | 0.243 | 0.464 | 0.691 | 0.263 | 0.050 | 0.611 | 0.593 | 0.258 | 0.149 | 0.663 | 0.558 | 0.423 | 0.069 | 0.717 | 0.522 | 0.378 | 0.100 | |

| The Netherlands | The Netherlands | Norway | Norway | Poland | Poland | |||||||||||||||||||

| P(2002) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.755 | 0.497 | 0.410 | 0.102 | 0.781 | 0.479 | 0.246 | 0.275 | 0.736 | 0.509 | 0.356 | 0.148 | 0.806 | 0.462 | 0.348 | 0.189 | 0.635 | 0.577 | 0.437 | 0.052 | 0.874 | 0.447 | 0.275 | 0.278 | |

| P(2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.746 | 0.503 | 0.427 | 0.101 | 0.765 | 0.490 | 0.266 | 0.244 | 0.698 | 0.535 | 0.379 | 0.114 | 0.737 | 0.509 | 0.294 | 0.197 | 0.722 | 0.519 | 0.412 | 0.057 | 0.874 | 0.417 | 0.292 | 0.291 | |

| P(2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.723 | 0.518 | 0.445 | 0.078 | 0.703 | 0.504 | 0.289 | 0.207 | 0.667 | 0.555 | 0.370 | 0.107 | 0.703 | 0.532 | 0.324 | 0.144 | 0.594 | 0.604 | 0.392 | 0.048 | 0.683 | 0.545 | 0.300 | 0.155 | |

| P(2014) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.791 | 0.473 | 0.502 | 0.072 | 0.816 | 0.456 | 0.355 | 0.188 | 0.716 | 0.522 | 0.374 | 0.126 | 0.745 | 0.503 | 0.350 | 0.147 | 0.597 | 0.602 | 0.403 | 0.047 | 0.704 | 0.531 | 0.320 | 0.149 | |

| P(2018) | 0.726 | 0.516 | 0.439 | 0.091 | 0.760 | 0.494 | 0.349 | 0.158 | 0.777 | 0.482 | 0.376 | 0.145 | 0.799 | 0.467 | 0.386 | 0.146 | 0.646 | 0.570 | 0.446 | 0.041 | 0.759 | 0.494 | 0.367 | 0.139 |

| Portugal | Portugal | Slovenia | Slovenia | Spain | Spain | |||||||||||||||||||

| P(2002) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.650 | 0.567 | 0.132 | 0.025 | 0.650 | 0.418 | 0.022 | 0.560 | 0.689 | 0.541 | 0.323 | 0.108 | 0.831 | 0.446 | 0.247 | 0.307 | 0.565 | 0.623 | 0.256 | 0.029 | 0.559 | 0.627 | 0.145 | 0.227 | |

| P(2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.625 | 0.583 | 0.188 | 0.016 | 0.744 | 0.504 | 0.116 | 0.380 | 0.696 | 0.536 | 0.347 | 0.111 | 0.828 | 0.448 | 0.283 | 0.270 | 0.693 | 0.538 | 0.335 | 0.042 | 0.657 | 0.562 | 0.239 | 0.199 | |

| P(2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.683 | 0.545 | 0.212 | 0.026 | 0.763 | 0.491 | 0.086 | 0.423 | 0.696 | 0.536 | 0.343 | 0.077 | 0.839 | 0.440 | 0.291 | 0.269 | 0.672 | 0.552 | 0.322 | 0.041 | 0.646 | 0.570 | 0.245 | 0.185 | |

| P(2014) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.684 | 0.544 | 0.269 | 0.041 | 0.698 | 0.535 | 0.148 | 0.317 | 0.670 | 0.553 | 0.367 | 0.075 | 0.742 | 0.505 | 0.315 | 0.180 | 0.703 | 0.531 | 0.350 | 0.055 | 0.681 | 0.546 | 0.357 | 0.192 | |

| P(2018) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.522 | 0.652 | 0.284 | 0.024 | 0.479 | 0.680 | 0.178 | 0.142 | 0.666 | 0.556 | 0.383 | 0.060 | 0.787 | 0.475 | 0.337 | 0.188 | 0.681 | 0.546 | 0.374 | 0.050 | 0.667 | 0.555 | 0.287 | 0.157 | |

| Sweden | Sweden | Switzerland | Switzerland | UK | UK | |||||||||||||||||||

| P(2002) | NA | NA | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.723 | 0.518 | 0.329 | 0.146 | 0.805 | 0.463 | 0.300 | 0.237 | 0.736 | 0.510 | 0.298 | 0.077 | 0.732 | 0.512 | 0.260 | 0.228 | |

| P(2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.789 | 0.474 | 0.464 | 0.117 | 0.803 | 0.447 | 0.325 | 0.228 | 0.676 | 0.549 | 0.345 | 0.110 | 0.766 | 0.489 | 0.303 | 0.207 | 0.754 | 0.497 | 0.328 | 0.078 | 0.753 | 0.498 | 0.323 | 0.179 | |

| P(2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.732 | 0.512 | 0.446 | 0.098 | 0.784 | 0.478 | 0.321 | 0.202 | 0.644 | 0.571 | 0.306 | 0.096 | 0.731 | 0.512 | 0.301 | 0.187 | 0.731 | 0.513 | 0.358 | 0.113 | 0.774 | 0.484 | 0.286 | 0.230 | |

| P(2014) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.758 | 0.495 | 0.420 | 0.112 | 0.814 | 0.458 | 0.354 | 0.188 | 0.650 | 0.567 | 0.314 | 0.105 | 0.720 | 0.520 | 0.323 | 0.157 | 0.698 | 0.535 | 0.390 | 0.101 | 0.753 | 0.498 | 0.335 | 0.167 | |

| P(2018) | 0.751 | 0.499 | 0.397 | 0.123 | 0.791 | 0.473 | 0.383 | 0.144 | 0.621 | 0.586 | 0.305 | 0.091 | 0.700 | 0.533 | 0.324 | 0.142 | 0.710 | 0.527 | 0.427 | 0.096 | 0.759 | 0.494 | 0.384 | 0.122 |

| Total | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| P(2002) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.603 | 0.598 | 0.290 | 0.110 | 0.603 | 0.574 | 0.174 | 0.252 | |||||||||||||||||

| P(2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.616 | 0.589 | 0.326 | 0.101 | 0.642 | 0.572 | 0.212 | 0.216 | |||||||||||||||||

| P(2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.585 | 0.610 | 0.327 | 0.081 | 0.631 | 0.579 | 0.226 | 0.195 | |||||||||||||||||

| P(2014) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.635 | 0.577 | 0.345 | 0.094 | 0.633 | 0.578 | 0.214 | 0.208 | |||||||||||||||||

| P(2018) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.669 | 0.554 | 0.411 | 0.081 | 0.678 | 0.548 | 0.293 | 0.159 | |||||||||||||||||

Figure A1.

The differences in upward mobility index between nominal and positional mobility by country and ESS round (ESS1, ESS3, ESS5, ESS7, and ESS9).

Figure A2.

The differences in and between nominal and positional mobility by country and ESS round (ESS1, ESS3, ESS5, ESS7, ESS9).

References

- Hout, M.; DiPrete, T. What we have learned: RC28’s contributions to knowledge about social stratification. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2006, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensoy, O.; DiAngelo, R. Is Everyone Really Equal?: An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, R. (Ed.) Social Mobility in Europe; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, R.; Muller, W. (Eds.) Education and Intergenerational Mobility in Europe and the United States; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, R.; Goldthorpe, J. The Constant Flux; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Blanden, J. Cross-Country Ranking in Intergenerational Mobility: A Comparison of Approaches from Economics and Sociology. J. Econ. Surv. 2011, 63, 38–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torche, F. Analyses of Intergenerational Mobility: An Interdisciplinary Review. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2015, 657, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, R.; Goldthorpe, J.H. Explaining Educational Differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. Ration. Soc. 1997, 9, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanden, J.; Gregg, P.; Machin, S. Intergenerational Mobility in Europe and North America; A Report Supported by the Sutton Trust; Centre for Economic Performance: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bukodi, E.; Goldthorpe, J.H. Social Mobility and Education in Britain: Research, Politics and Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Salvanes, K.G. What Drives Intergenerational Mobility? The Role of Family, Neighborhood, Education, and Social Class: A Review of Bukodi and Goldthorpe’s Social Mobility and Education in Britain. J. Econ. Lit. 2023, 61, 1540–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corak, M. Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F.; Heckman, J. The Technology of Skill Formation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanden, J.; Machin, S. Recent Changes in Intergenerational Mobility in Britain; Sutton Trust: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Symeonaki, M.; Stamatopoulou, G. Exploring the transition to Higher Education in Greece: Issues of intergenerational educational mobility. Policy Futures Educ. 2014, 12, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonaki, M.; Stamatopoulou, G.; Michalopoulou, C. Intergenerational educational mobility in Greece: Transitions and social distances. Commun. Stat.—Theory Methods 2015, 45, 1710–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulou, G.; Symeonaki, M.; Michalopoulou, C. Occupational and educational gender segregation in southern Europe. In Stochastic and Data Analysis Methods and Applications in Statistics and Demography; Bozeman, J.R., Oliveira, T., Skiadas, C.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 611–619. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatopoulou, G.; Symeonaki, M. Intergenerational social mobility in Europe: Findings from the European Social Survey. In The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Symeonaki, M.; Tsinaslanidou, P. Assessing the Intergenerational Educational Mobility in European Countries Based on ESS Data: 2002–2016; The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis Quantitative Methods in Demography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, R.; Luijkx, R.; Müller, W.; Pollak, R. Nonpersistent inequality in educational attainment: Evidence from eight European countries. Am. J. Sociol. 2009, 114, 1475–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, R.; Luijkx, R.; Müller, W.; Pollak, R. Long-term trends in educational inequality in Europe: Class inequalities and gender differences. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldthorpe, J.H. Analysing Social Inequality: A Critique of Two Recent Contributions from Economics and Epidemiology. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 26, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, F. Social Limits to Growth; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rotman, A.; Shavit, Y.; Shalev, M. Nominal and positional perspectives on educational stratification in Israel. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 43, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, S.; Ishida, H. The absolute and relative values of education and the inequality of educational opportunity: Trends in access to education in postwar Japan. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 43, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triventi, M.; Panichella, N.; Ballarino, G.; Barone, C.; Bernardi, F. Education as a positional good: Implications for social inequalities in educational attainment in Italy. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 43, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, V.; Bol, T.; Van de Werfhorst, H.G. What makes education positional? Institutions, overeducation and the competition for jobs. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 43, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, S. Educational Expansion, Skills Diffusion, and the Economic Value of Credentials and Skills. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 85, 128–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D.J. Stochastic Models for Social Processes, 3rd ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, D.J.; Forbes, A.F.; McClean, S.I. Statistical Techniques for Manpower Planning, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McClean, S. Semi-Markov models for manpower planning. In Semi-Markov Models; Janssen, J., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- McClean, S. Manpower planning models and their estimation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1991, 51, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, S.; Montgomery, E. Estimation for Semi-Markov Manpower Models in a Stochastic Environment. In Semi-Markov Models and Applications; Janssen, J., Limnios, N., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliou, P.-C.G. Asymptotic behavior of Markov systems. J. Appl. Probab. 1982, 19, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, P.-C.G.; Symeonaki, M. The perturbed non-homogeneous Markov system. Linear Algebra Appl. 1999, 289, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, P.-C.G. Non-Homogeneous Markov Set Systems. Mathematics 2021, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, P.-C.G. Non-Homogeneous Markov Chains and Systems: Theory and Applications, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bibby, J. Methods of measuring mobility. In Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1975; Volume 9, pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Goldthorpe, J.H.; Jackson, M. Intergenerational class mobility in contemporary Britain: Political concerns and empirical findings. Br. J. Sociol. 2007, 58, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prais, S. Measuring social mobility. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1955, 118, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorrocks, A. The measurement of social mobility. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukodi, E.; Goldthorpe, J.H. Educational attainment—Relative or absolute—As a mediator of intergenerational class mobility in Britain. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 43, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).