1. Introduction

Under specific circumstances, nonlinear controllers offer notable advantages compared to linear controllers. This is particularly evident when dealing with nonlinear plant dynamics and/or system measurements [

1,

2,

3,

4], nonadditive or non-Gaussian plant/measurement disturbances, nonquadratic performance measures [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], uncertain plant models [

10,

11,

12], or constrained control signals/state amplitudes [

13,

14]. In the work by [

15], the current status of deterministic continuous-time nonlinear-nonquadratic optimal control problems is presented, emphasizing the use of Lyapunov functions for stability and optimality (see [

15,

16,

17] and the references therein).

Expanding on the findings of [

15,

16,

18,

19], this paper introduces a framework for analyzing and designing feedback controllers for nonlinear stochastic dynamical systems. Specifically, it addresses a feedback stochastic optimal control problem with a nonlinear-nonquadratic performance measure over an infinite horizon. The key is the connection between the performance measure and a Lyapunov function, ensuring asymptotic stability in probability for the nonlinear closed-loop system. The framework establishes the groundwork for extending linear-quadratic control to nonlinear-nonquadratic problems in stochastic dynamical systems.

The focus lies on the role of the Lyapunov function in ensuring stochastic stability and its seamless connection to the steady-state solution of the stochastic Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation, characterizing the optimal nonlinear feedback controller. To simplify the solution of the stochastic steady-state Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation, the paper adopts an approach of parameterizing a family of stochastically stabilizing controllers. This corresponds to addressing an inverse optimal stochastic control problem [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The inverse optimal control design approach constructs the Lyapunov function for the closed-loop system, serving as an optimal value function. It achieves desired stability margins, particularly for nonlinear inverse optimal controllers minimizing a meaningful nonlinear-nonquadratic performance criterion. The paper derives stability margins for optimal and inverse optimal nonlinear stochastic feedback regulators, considering gain, sector, and disk margin guarantees. These guarantees are obtained for nonlinear stochastic dynamical systems controlled by nonlinear optimal and inverse optimal Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman controllers.

Furthermore, the paper establishes connections between stochastic stability margins, stochastic meaningful inverse optimality, and stochastic dissipativity [

27,

28], showcasing the equivalence between stochastic dissipativity and optimality for stochastic dynamical systems. Specifically, utilizing extended Kalman–Yakubovich–Popov conditions characterizing stochastic dissipativity, our optimal feedback control law satisfies a return difference inequality predicated on the infinitesimal generator of a controlled Markov diffusion process, connecting optimality to stochastic dissipativity with a specific quadratic supply rate. This integrated framework provides a comprehensive understanding of optimal nonlinear control strategies for stochastic dynamical systems, encompassing stability, optimality, and dissipativity considerations.

2. Mathematical Preliminaries

We start by reviewing some basic results on nonlinear stochastic dynamical systems [

29,

30,

31,

32]. First, however, we require some definitions. A

sample space is the set of possible outcomes of an experiment. Given a sample space

, a

-

algebra on

is a collection of subsets of

such that

, if

, then

, and if

, then

. The pair (

) is called a

measurable space and the

probability measure defined on (

) is a function

such that

. Furthermore, if

and

,

, then

. The triple (

) is called a

probability space. The subsets of

belonging to

are called

-

measurable sets. A probability space is

complete if every subset of every null set is measurable.

The -algebra generated by the open sets in , denoted by , is called the Borel σ-algebra and the elements of are called Borel sets. Given the probability space (), a random variable is a real-valued mapping such that for all Borel sets . That is, x is -measurable. A stochastic process is a collection of random variables defined on the complete probability space indexed by the set that take values on a common measurable space . Since , we say that is a continuous-time stochastic process.

Occasionally, we write for to denote the explicit dependence of the random variable on the outcome . For every fixed time , the random variable assigns a vector to every outcome , and for every fixed , the mapping generates a sample path of the stochastic process , where for convenience we write to denote the stochastic process . In this paper, and .

A

filtration on

is a collection of sub-

-fields of

, indexed by

, such that

,

. A filtration is

complete if

contains the

-negligible sets. The stochastic process

is

progressively measurable with respect to

if, for every

, the map

defined on

is

-measurable, where

denotes the Borel

-algebra on

. The stochastic process

is said to be

adapted with respect to

, or simply

-adapted, if

is

-measurable for every

. An adapted stochastic process with right continuous (or left continuous) sample paths is progressively measurable [

33]. We say that a stochastic process satisfies the

Markov property if the conditional probability distribution of the future states of the stochastic process depends only on the present state.

The stochastic process

is a

martingale with respect to the filtration

if it is

-adapted,

, and

, where

denotes expectation and

denotes conditional expectation. If we replace the equality in

with “≤" (respectively, “≥"), then

is a

supermartingale (respectively,

submartingale). For an additional discussion on stochastic processes, filtrations, and martingales, see [

33].

In this paper, we consider controlled stochastic dynamical systems

of the form

where (

1) is a stochastic differential equation and (2) is an output equation. The stochastic processes

,

, and

represent the system state, input, and output, respectively. Here,

is a set of

admissible inputs that contains the input processes

that can be applied to the system,

is a random system initial condition vector, and

is a

d-dimensional Brownian motion process. For every

, the random variables

,

, and

take values in the state space

, the control space

, and the output space

, respectively. The measurable mappings

,

, and

are known as the system drift, diffusion, and output functions.

The stochastic differential Equation (

1) is interpreted as a way of expressing the integral equation

where the first integral in (

3) is a Lebesgue integral and the second integral is an Itô integral [

34]. When considering processes whose initial condition is a fixed deterministic point rather than a distribution, we will find it convenient to introduce the notation

to denote the solution process at time

t when the initial condition at time

s is the fixed point

almost surely. Similarly,

and

denote probability and expected value, respectively, given that the initial condition

is the fixed point

almost surely.

Let

be a fixed complete filtered probability space,

be a

-adapted Brownian motion,

be a

-valued

-progressively measurable input process, and

be a

-measurable initial condition. A solution to (

1) with input

is a

-valued

-adapted process

with continuous sample paths such that the integrals in (

3) exist and (

3) holds almost surely (a.s.) for all

. For a Brownian motion disturbance, input process, and initial condition given in a prescribed probability space, the solution to (

3) is known as a strong solution [

35]. In this paper, we focus on strong solutions, and we will simply use the term “solution” to refer to a strong solution. A solution to (

1) is

unique if for any two solutions

and

that satisfy (

1),

for all

almost surely.

We assume that every

is a

-valued Markov control process. An input process

is a

Markov control process if there exists a function

such that

. Note that the class of Markov controls encompasses both time-varying inputs (i.e., possibly open-loop control input processes) as well as state-dependent inputs (i.e., possibly a

state feedback control input , where

is a

feedback control law). If

is a Markov control process, then the stochastic differential Equation (

1) is an Itô diffusion, and if its solution is unique, then the solution is a

Markov process.

For an Itô diffusion system with solution

, the (infinitesimal) generator

of

is an operator acting on the continuous function

and is defined as ([

31])

The set of functions

for which the limit in (

4) exists is denoted by

. If

has compact support, where

denotes the space of two-times continuously differentiable functions on

, then

and

, where

and where we write

for the gradient of

V at

x and

for the Hessian of

V at

x.

Note that the differential operator

introduced in (

5) is defined for every

and it is characterized by the system drift and diffusion functions. We will refer to the differential operator

as the (infinitesimal) generator of the system

. However, if discontinuous control inputs in the state variables are considered, then the concept of the

extended generator [

36] should be used.

If

, then it follows from

Itô’s formula [

35] that the stochastic process

satisfies

If the terms appearing in (

6) are integrable and the Itô integral in (

6) is a martingale, then it follows from (

6) that

The next result is standard and establishes existence and uniqueness of solutions for the controlled Itô diffusion system (

1).

Theorem 1 ([

32])

. Consider the stochastic dynamical system (1) with initial condition such that . Let be a Markov control process given by , such that the following conditions hold:- (i)

Local Lipschitz continuity.

For every , there exists a constant such thatfor every with , and every .- (ii)

Linear growth.

There exists a constant such that, for all and ,

Then, there exists a unique solution to (1) with input . Furthermore, Assumption 1. For the remainder of the paper we assume that the conditions for existence and uniqueness given in Theorem 1 are satisfied for the system (1) and (2). 3. Stability Theory for Stochastic Dynamical Systems

Given a feedback control law

, the

closed-loop system (

1) takes the form

where, for convenience, we have defined the closed-loop drift function

and we have omitted the dependence of

D on its second parameter so that

. In this case, the infinitesimal generator of the closed-loop system (

11) is given by

Next, we define the notion of stochatic stability for the closed loop system (

11). An

equilibrium point of (

11) is a point

such that

and

. If

is an equilibrium point of (

11), then the constant stochastic process

is a solution of (

11) with initial condition

. The following definition introduces several notions of stability in probability for the equilibrium solution

of the stochastic dynamical system (

11). Here, the initial condition

is assumed to be a constant, and hence, whenever we write

we mean that

is a constant vector. It is important to note that if we assume that

is a

random vector, then we replace

with

almost surely in Definition 1. As shown in ([

32], p. 111) this is without loss of generality in addressing stochastic stability of an equilibrium point.

Definition 1 ([

29,

32])

. The equilibrium solution to (11) is Lyapunov stable in probability

if, for every ,Equivalently, the equilibrium solution to (11) is Lyapunov stable in probability if, for every and , there exists such that, for all , The equilibrium solution to (11) is asymptotically stable in probability

if it is Lyapunov stable in probability andEquivalently, the equilibrium solution to (11) is asymptotically stable in probability if it is Lyapunov stable in probability and, for every , there exists such that if , then ( The equilibrium solution to (11) is globally asymptotically stable in probability

if it is Lyapunov stable in probability and, for all , ( The equilibrium solution to (11) is exponentially

p-stable in probability

if there exist scalars , and , and such that if , thenIf, in addition, (18) holds for all , then the equilibrium solution to (11) is globally exponentially

p-stable in probability

. Finally, if , we say that the equilibrium solution to (11) is globally exponentially mean square stable in probability.

We now provide sufficient conditions for local and global asymptotic stability in probability for the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system (

11).

Theorem 2 ([

29])

. Let be an open subset containing the point . Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system (11) and assume that there exists a two-times continuously differentiable function such thatThe equilibrium solution to (11) is then Lyapunov stable in probability. If, in addition,then the equilibrium solution to (11) is asymptotically stable in probability. Finally, if, in addition, and V is radially unbounded, then the equilibrium solution to (11) is globally asymptotically stable in probability. Finally, the next result gives a Lyapunov theorem for global exponential stability in probability.

Theorem 3 ([

29])

. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system (11) and assume that there exist a two-times continuously differentiable function and scalars α, β, , and such thatThen the equilibrium solution to (11) is globally exponentially p-stable in probability. 6. Optimal Nonlinear Feedback Control for Stochastic Systems

In this section, we consider a control problem involving a notion of optimality with respect to a nonlinear-nonquadratic cost functional. We use the results developed in Theorem 6 to characterize optimal feedback controllers that guarantee closed-loop global stabilization in probability. Specifically, sufficient conditions for optimality are given in a form that corresponds to a steady-state version of the stochastic Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation. For the following result, let and be such that and .

Theorem 7. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (1) with nonlinear-nonquadratic performance measurewhere is the solution to (1) with control input . Furthermore, assume that there exists a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function , and a feedback control law such thatwhereThen, with the feedback control , the zero solution of the closed-loop system (11) is globally asymptotically stable in probability, andIn addition, the feedback control minimizes (45) in the sense thatwhere denotes the set of controllers given bywhere and . Proof. Global asymptotic stability in probability is a direct consequence of (

46)–(49) by applying Theorem 6 to the closed-loop system (

11). Furthermore, using (50), (

53) is a restatement of (37) as applied to the closed-loop system.

To show that

, note that (49) and (50) imply that

. Thus,

Now, using an analogous argument as in the proof of Theorem 6, it follows that

for

, and hence,

.

Next, let

, and note that, by Itô’s lemma [

31],

Now, it can be shown that the stochastic integral in (

57) is a martingale using a similar argument as the one given in the proof of Theorem 6. Hence,

where

exists since

and (

10) holds. Next, taking the limit as

yields

Since

, the control law satisfies

, and hence, it follows from (

59) that

Now, combining (51) and (

60) yields

Next, note that, for every

,

and, since

,

. Thus, it follows from the dominated convergence theorem [

39] that

Finally, combining (

53), (

61), and (

63) yields

which proves (

54). □

Note that (50) is the steady-state version of the stochastic Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation. To see this, recall that the

stochastic Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation is given by

which characterizes the optimal control for stochastic time-varying systems on a finite or infinite time interval [

30]. For infinite horizon time-invariant systems,

, and hence, (

65) collapses to (50) and (51), which guarantee optimality with respect to the set of admissible controllers

. Note that an explicit characterization of the set

is not required and the optimal stabilizing

feedback control law

is independent of the initial condition

.

In order to ensure global asymptotic stability in probability of the closed-loop system (

11), Theorem 7 requires that

V satisfy (

46), (47), and (49), which implies that

V is a Lyapunov function for the closed-loop system (

11). However, for optimality

V need not satisfy (

46), (47), and (49). Specifically, if

V is a two-times continuously differentiable function such that

and

, then (50) and (51) imply (

53) and (

54). It is important to note here that, unlike deterministic theory ([

16], p. 857), to ascertain that a control is optimal we require the additional

transversality condition appearing in (

55); see ([

40], p. 337), ([

41], p. 125), and ([

42], p. 139) for further details.

Even though for an optimal controller

the transversality condition in (

55) is satisfied, the transversality condition involves a sample path dependent condition that can be difficult to verify for an arbitrary control input

. The next theorem circumvents this problem by requiring additional restrictions on the cost integrand

L and the Lyapunov function

V.

Theorem 8. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (1) with the nonlinear-nonquadratic performance measure (45) where satisfiesfor some positive constants γ and . Assume that there exist a two-times continuously differentiable function and a control law such that (48), (50), and (51) hold and, for positive constants α and β,Then, with the feedback control , the zero solution of the closed-loop system (11) is globally exponentially p-stable in probability and (53) holds. In addition, the feedback control minimizes (45) in the sense thatwhere denotes the set of controllers given byand . Proof. Global exponential

p-stability in probability is a direct consequence of (

66), (

67), and (50) by applying Theorem 3 to the closed-loop system (

11). To show (

53), (

68), and

, first note that Theorem 7 holds. Therefore, we need only show that with (

66) and (

67),

. That is, any input

with finite cost (and hence, belonging to

) automatically satisfies the transversality condition (and hence, belongs to

).

Assume that (

66) and (

67) hold. Note that

is immediate. To show

, let

and

. Since

,

and hence, it follows from the dominated convergence theorem [

39] that

Furthermore, by Tonelli’s theorem [

37],

Combining (

66) and (

70)–(

72) we obtain

Now, using Lemma 5.7 of [

29], it follows that

which, combined with (

67), yields

Hence,

, which implies

. Thus,

. □

Next, we specialize Theorem 8 to linear stochastic dynamical systems and provide connections to the stochastic optimal linear-quadratic regulator problem with multiplicative noise. For the following result, let , , , and let and be given positive definite matrices.

Corollary 2. Consider the linear controlled stochastic dynamical system with multiplicative noise given byand with quadratic performance measureFurthermore, assume that there exists a positive-definite matrix such thatThen, with the feedback control , the zero solution to (76) is globally exponentially mean-square stable in probability andFurthermore,where is the set of controllers defined in (69) for (76) and . Proof. The result is a direct consequence of Theorem 8 with

,

,

, and

. Specifically, (

66) is satisfied with

and

. Moreover,

V is a two-times continuously differentiable function that satisfies

and (

67) with

,

, and

. Furthermore, condition (48) is trivially satisfied. Next, it follows from (

78) that

, showing that (50) holds. Finally,

so that all of the conditions of Theorem 8 are satisfied. □

The optimal feedback control law in Corollary 2 is derived using the properties of H as defined in Theorem 7. Specifically, since it follows that . Now, gives the unique global minimum of H. Hence, since minimizes it follows that satisfies or, equivalently, .

7. Inverse Optimal Stochastic Control

In this section, we specialize Theorem 7 to systems that are affine in the control. Specifically, we devise nonlinear feedback controllers within a stochastic optimal control framework, aiming to minimize a nonlinear-nonquadratic performance criterion. This is achieved by selecting the controller in such a way that the mapping of the infinitesimal generator of the Lyapunov function is negative definite along the sample trajectories of the closed-loop system. We also establish sufficient conditions for the existence of asymptotically stabilizing solutions (in probability) to the stochastic Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation. Consequently, these findings present a set of globally stabilizing controllers, parameterized by the minimized cost functional.

The controllers developed in this section are based on an inverse optimal stochastic control problem [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. To simplify the solution of the stochastic steady-state Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation, we do not attempt to minimize a

given cost functional. Instead, we parameterize a family of stochastically stabilizing controllers that minimize a

derived cost functional, offering flexibility in defining the control law. The performance integrand explicitly depends on the nonlinear system dynamics, the Lyapunov function for the closed-loop system, and the stabilizing feedback control law. This coupling is introduced through the stochastic Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation. Therefore, by adjusting parameters in the Lyapunov function and the performance integrand, the proposed framework can characterize a class of globally stabilizing controllers in probability, meeting specified constraints on the closed-loop system response.

Consider the nonlinear stochastic affine in the control dynamical system given by

where

satisfies

,

, and

satisfies

. Furthermore, we consider performance integrands

L of the form

where

, and

, and where

denotes the set of

positive definite matrices, so that (

45) becomes

Theorem 9. Consider the nonlinear controlled affine stochastic dynamical system (81) with performance measure (83). Assume that there exists a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function and a function such thatThen the zero solution of the closed-loop system is globally asymptotically stable in probability with the feedback control lawand the performance measure (83), withis minimized in the sense thatFinally, Proof. The result is a direct consequence of Theorem 7 with

,

, and

. Specifically, with (

82) the Hamiltonian has the form

Now, the feedback control law (

90) is obtained by setting

. With (

90), it follows that (

84), (85), and (88) imply (

46), (47), and (49), respectively. Next, since

V is two-times continuously differentiable and

is a local minimum of

V, it follows that

, and hence, since by assumption

, it follows that

, which implies (48). Next, with

given by (

91) and

given by (

90), (50) holds. Finally, since

and

is positive definite for all

, condition (51) holds. The result now follows as a direct consequence of Theorem 7. □

Note that (88) is equivalent to

with

given by (

90). Furthermore, conditions (

84), (85), and (

94) ensure that

V is a Lyapunov function for the closed-loop system (

89). As outlined in [

16], it is crucial to acknowledge that the function

present in the integrand of the performance measure (

82) is a variable function of

constrained by conditions (86) and (88). Therefore,

offers versatility in the selection of the control law.

With

given by (

91) and

given by (

90),

L is given by

Since

,

, the first term on the right-hand side of (95) is nonnegative, whereas (

94) implies that the second, third, and fourth terms collectively are nonnegative. Thus, it follows that

which shows that

L may be negative. As a result, there may exist a control input

for which the performance measure

is negative. However, if the control

is a regulation controller, that is,

, then it follows from (

92) and (

93) that

Furthermore, in this case, substituting

into (95) yields

which, by (

94), is positive.

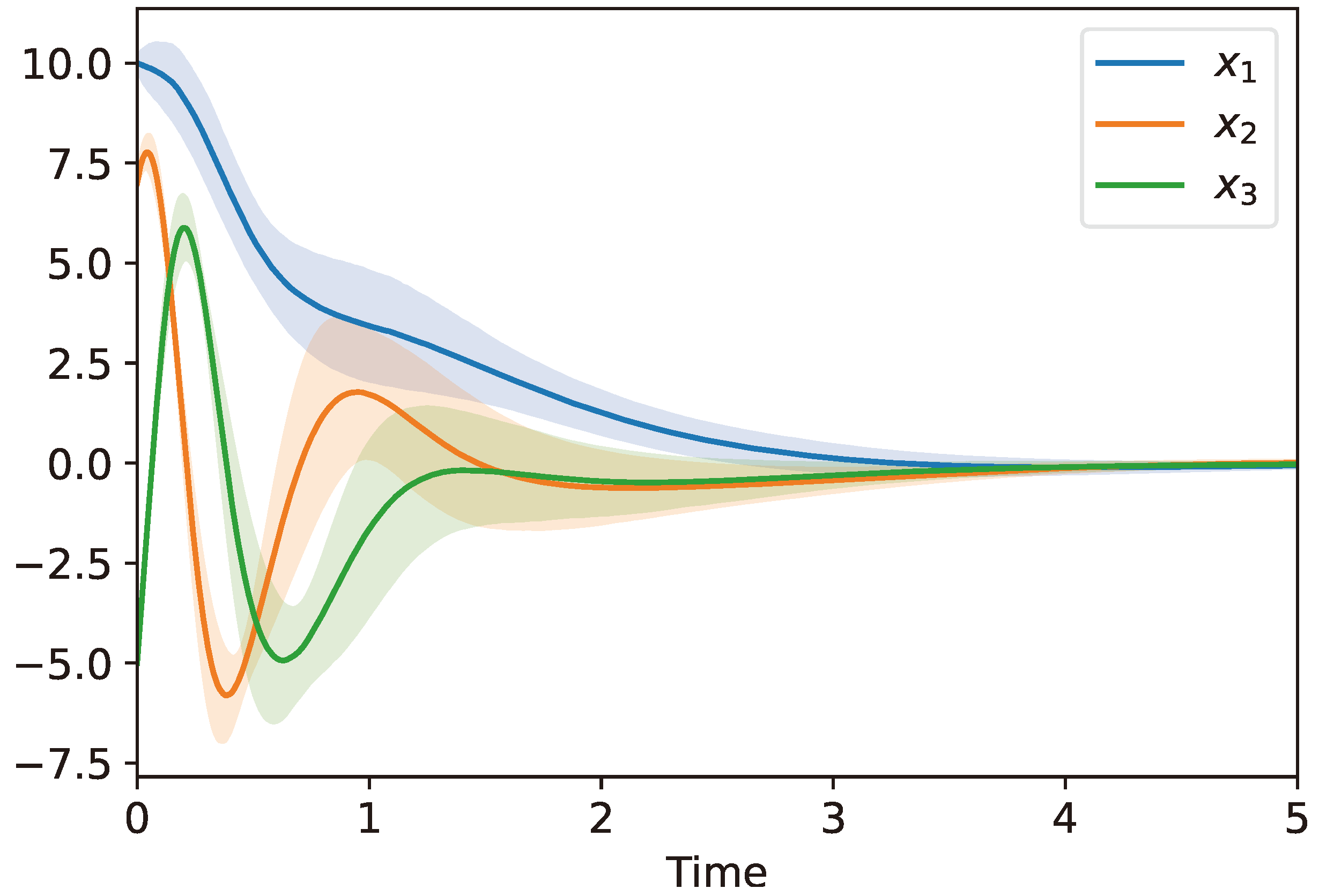

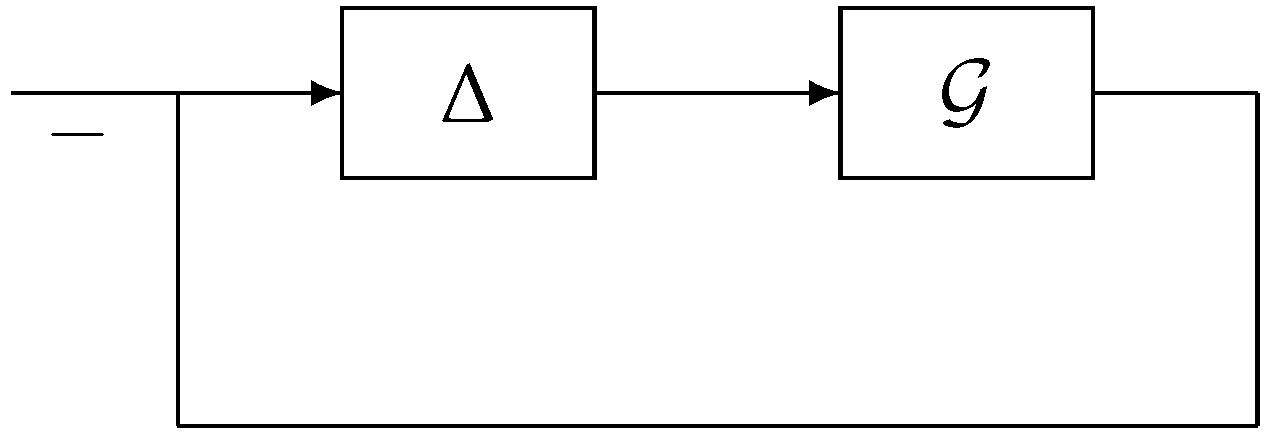

Example 1. To illustrate the utility of Theorem 9, we showcase an example involving global stabilization of a stochastic version of the Lorentz equations [43]. These equations model fluid convection and are known to exhibit chaotic behavior. To construct inverse optimal controllers for the controlled Lorentz stochastic dynamical system consider the systemwhere , and . Note that (99)–(101) can be written in the form of (81) with In order to design an inverse optimal control law for the controlled Lorentz stochastic dynamical system (99)–(101) consider the quadratic Lyapunov function candidate given bywhere and . Now, letting , , , , and , where , it follows thatsatisfies (88); that is,Hence, the feedback control law given by (90) globally stabilizes the controlled Lorentz dynamical system (99)–(101). Furthermore, the performance functional (83), withis minimized in the sense of (92). Figure 1 shows the mean along with the standard deviation of 1000 system sample paths with parameters , , and . ▵

The next theorem is similar to Theorem 9 and is included here as it provides the basis for our stability margin results given in the next sections.

Theorem 10. Consider the nonlinear controlled affine stochastic dynamical system (81) with performance measure (83). Assume that there exists a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function such thatThen the zero solution of the closed-loop systemis globally asymptotically stable in probability with the feedback control lawand the performance functional (83) is minimized in the sense thatFinally, Proof. The proof is identical to the proof of Theorem 9 and, hence, is omitted. □

8. Relative Stability Margins for Optimal Nonlinear Stochastic Regulators

In this section, we establish relative stability margins for both optimal and inverse optimal nonlinear stochastic feedback regulators. Specifically, we derive sufficient conditions ensuring gain, sector, and disk margin guarantees for nonlinear stochastic dynamical systems under the control of nonlinear optimal and inverse optimal Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman controllers. These controllers aim to minimize a nonlinear-nonquadratic performance criterion that includes cross-weighting terms. In the scenario where the cross-weighting term in the performance criterion is omitted, our findings align with the gain, sector, and disk margins derived for the deterministic optimal control problem outlined in [

25].

Alternatively, by retaining the cross-terms in the performance criterion and specializing the optimal nonlinear-nonquadratic problem to a stochastic linear-quadratic problem featuring a multiplicative noise disturbance, our results recover the corresponding gain and phase margins for the deterministic linear-quadratic optimal control problem as presented in [

44]. Despite the observed degradation of gain, sector, and disk margins due to the inclusion of cross-weighting terms, the added flexibility afforded by these terms enables the assurance of optimal and inverse optimal nonlinear controllers that can exhibit superior transient performance as compared to meaningful inverse optimal controllers.

To develop relative stability margins for nonlinear stochastic regulators consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system

given by

where

satisfies

,

,

satisfies

, and

is an admissible feedback controller such that

is globally asymptotically stable in probability with

, with a nonlinear-nonquadratic performance criterion

where

,

, and

are given such that

,

, and

.

Next, we define the relative stability margins for

given by (

114) and (115). Specifically, let

,

, and consider the negative feedback interconnection

of

and

given in

Figure 2, where

is either a linear operator

, a nonlinear static operator

, or a nonlinear dynamic operator

with input

and output

. Furthermore, we assume that in the nominal case

the nominal closed-loop system is globally asymptotically stable in probability.

Definition 3 ([

16])

. Let be such that . Then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115) is said to have a gain margin

if the negative feedback interconnection of and is globally asymptotically stable in probability for all , where , . Definition 4 ([

16])

. Let be such that . Then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115) is said to have a sector margin

if the negative feedback interconnection of and is globally asymptotically stable in probability for all nonlinearities such that , , and , for all , . Definition 5. A nonlinear stochastic dynamical systems is asymptotically zero-state observable if and imply .

For the next two definitions, we assume that the system and the nonlinear operator are asymptotically zero-state observable.

Definition 6 ([

16])

. Let be such that . Then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115) is said to have a disk margin

if the negative feedback interconnection of and Δ is globally asymptotically stable in probability for all dynamic operators Δ such that Δ is stochastically dissipative with respect to the supply rate and with a two-times continuously differentiable, positive definite storage function, where , , and such that . Definition 7 ([

16])

. Let be such that . Then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115) is said to have a structured disk margin

if the negative feedback interconnection of and Δ is globally asymptotically stable in probability for all dynamic operators Δ such that , and , , is stochastically dissipative with respect to the supply rate and with a two-times continuously differentiable, positive definite storage function, where , , and such that . Note that if has a disk margin , then has gain and sector margins .

The following lemma is needed for developing the main results of this section.

Lemma 1. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115), where ϕ is a stochastically stabilizing feedback control law given by (111) and where V satisfiesFurthermore, suppose there exists such that andThen,for all and . Proof. Note that it follows from (

117) and (

118) that, for all

and

,

which implies that

This completes the proof. □

Next, we present disk margins for the nonlinear-nonquadratic optimal regulator given by Theorem 10. We consider the case in which , , is a constant diagonal matrix and the case in which it is not a constant diagonal matrix.

Theorem 11. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115), where ϕ is the stochastically stabilizing feedback control law given by (111) and where is a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function that satisfies (105)–(109). Assume that is asymptotically zero state observable. If the matrix , where , , and there exists such that and (118) is satisfied, then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system has a structured disk margin . If, in addition, and there exists such that and (118) is satisfied, then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system has a disk margin . Proof. Note that it follows from Lemma 1 that

Hence, with the storage function

, it follows from that

is stochastically dissipative with respect to the supply rate

. Now, the result is a direct consequence of Definitions 6 and 7, and the stochastic version of Corollary 6.2 given in [

16] with

and

. □

For the next result, define

where

is such that

and

.

Theorem 12. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115), where ϕ is the stochastically stabilizing feedback control law given by (111) and where is a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function that satisfies (105)–(109). Assume that is asymptotically zero-state observable. If there exists such that and (118) is satisfied, then the nonlinear stochastic system has a disk margin , where . Proof. It follows from Lemma 1 that

Thus, with the storage function

,

is stochastically dissipative with respect to thesupply rate

. The result now is a direct consequence of Definition 6 and the stochastic version of Corollary 6.2 given in [

16] with

and

. □

Next, we provide a result that guarantees sector and gain margins for the case in which , , is diagonal.

Theorem 13. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115), where ϕ is the stochastically stabilizing feedback control law given by (111) and where is a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function that satisfies (105)–(109). Furthermore, let , where , , . If there exists such that andthen the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system has a sector (and hence, gain) margin . Proof. Let

, where

is a static nonlinearity such that

,

, and

, for all

,

, where

and

; or, equivalently,

, for all

,

. In this case, the closed-loop system (

114) and (115) with

is given by

Next, consider the two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function Lyapunov function candidate

V satisfying (

105)–(109) and let

denote the Lyapunov infinitesimal generator of the closed-loop system (

126). Now, it follows from (109) and (

125) that

which, by Theorem 2, implies that the closed-loop system (

126) is globally asymptotically stable in probability for all

such that

,

,

. Hence,

given by (

114) and (115) has sector (and hence, gain) margins

. □

It is important to note that Theorem 13 also holds in the case where (

125) is replaced with (

118) and with the additional assumption that (

118) is radially unbounded. To see this, note that (

127) can be written as

where

In this case, the result follows from Theorem 3.1 of [

45]. Furthermore, note that in the case where

,

, is diagonal, Theorem 13 guarantees larger gain and sector margins to the gain and sector margin guarantees provided by Theorem 12. However, Theorem 13 does not provide disk margin guarantees.

10. Optimal Linear-Quadratic Stochastic Control

In this section, we specialize Theorems 11 and 12 to the case of linear stochastic systems with multiplicative disturbance noise. Specifically, consider the stabilizable stochastic linear system given by

where

,

,

, and

, and assume that

is detectable and the system (

139) and (140) is asymptotically stable in probability with the feedback

or, equivalently,

is Hurwitz, where

. Furthermore, assume that

K is an optimal regulator that minimizes the quadratic performance functional given by

where

,

, and

are such that

,

, and

is observable. In this case, it follows from Theorem 9 with

,

,

,

,

,

, and

that the optimal control law

K is given by

, where

is the solution to the algebraic regulator Riccati equation given by

The following results provide guarantees of disk, sector, and gain margins for the system (

139) and (140). We assume that

is asymptotically zero-state observable.

Corollary 3. Consider the stochastic dynamical system with multiplicative noise given by (139) and (140) and with performance functional (141), and let . Then, with , where satisfies (142), the system (139) and (140) has disk margin (and, hence, sector and gain margins) , where Proof. The result is a direct consequence of Theorem 12 with

,

,

,

,

, and

. Specifically, note that (

142) is equivalent to (109). Now, with

given by (

143), it follows that

, and hence, (

118) is satisfied so that all the conditions of Theorem 12 are satisfied. □

Corollary 4. Consider the stochastic dynamical system with multiplicative noise given by (139) and (140) and with performance functional (141), and let , where is diagonal. Then, with , where satisfies (142), the system (139) and (140) has structured disk margin (and hence, gain and sector) margin , where Proof. The result is a direct consequence of Theorem 11 with

,

,

,

,

, and

. Specifically, note that (

142) is equivalent to (109). Now, with

given by (

144), it follows that

, and hence, (

118) is satisfied so that all the conditions of Theorem 11 are satisfied. □

The gain margins specified in Corollary 4 precisely match those presented in [

44] for deterministic linear-quadratic optimal regulators incorporating cross-weighting terms in the performance criterion. Additionally, as Corollary 4 ensures structured disk margins of

, it implies that the system possesses a phase margin

defined as follows:

or equivalently,

In the scenario where

, deduced from (

144), it follows that

. Consequently, Corollary 4 ensures a phase margin of

in each input–output channel. Additionally, stipulating

leads to the conclusion, based on Corollary 4, that the system described by (

139) and (140) possesses a gain and sector margin of

.

11. Stability Margins and Meaningful Inverse Optimality

In this section, we establish explicit links between stochastic stability margins, stochastic meaningful inverse optimality, and stochastic dissipativity, focusing on a specific quadratic supply rate. More precisely, we derive a stochastic counterpart to the classical return difference inequality for continuous-time systems with continuously differentiable flows [

21,

46] in the context of stochastic dynamical systems. Furthermore, we establish connections between stochastic dissipativity and optimality for stochastic nonlinear controllers. Notably, we demonstrate the equivalence between stochastic dissipativity and optimality in the realm of stochastic dynamical systems. Specifically, we illustrate that an optimal nonlinear feedback controller

, satisfying a return difference condition based on the infinitesimal generator of a controlled Markov diffusion process, is equivalent to the stochastic dynamical system—with input

u and output

—being stochastically dissipative with respect to a supply rate expressed as

.

Here, we assume that

is nonnegative for all

, which, in the terminology of [

25,

47], corresponds to a

meaningful cost functional. Furthermore, we assume

and

,

, and is radially unbounded. In this case, we establish connections between stochastic dissipativity and optimality for nonlinear stochastic controllers. The first result specializes Theorem 10 to the case in which

.

Theorem 16. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system (114) with performance functional (83) with and , . Assume that there exists a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function such thatThen the zero solution of the closed-loop systemis globally asymptotically stable in probability with the feedback control lawand the performance functional (83) is minimized in the sense thatFinally, Proof. The proof is similar to the proof of Theorem 9, and hence, is omitted. □

Next, we show that for a given nonlinear stochastic dynamical system

given by (

114) and (115), there exists an equivalence between optimality and stochastic dissipativity. For the following result we assume that for a given nonlinear stochastic system (

114), if there exists a feedback control law

that minimizes the performance functional (

83) with

,

, and

,

, then there exists a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function

such that (149) is satisfied.

Theorem 17. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115). The feedback control law is optimal with respect to a performance functional (82) with , , and , , if and only if the nonlinear stochastic system is stochastically dissipative with respect to the supply rate and has a two-times continuously differentiable positive-definite, radially unbounded storage function . Proof. If the control law

is optimal with respect to a performance functional (

82) with

,

, and

,

, then, by assumption, there exists a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function

such that (149) is satisfied. Hence, it follows from Proposition 1 that

which implies that

is stochastically dissipative with respect to the supply rate

.

Conversely, if

is stochastically dissipative with respect to the supply rate

and has a two-times continuously differentiable positive-definite storage function

, then, with

,

,

,

, and

, it follows from the stochastic version of Theorem 5.6 of [

16] that there exists a function

such that

and, for all

,

Now, the result follows from Theorem 16 with

. □

The next result gives disk and structured disk margins for the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system

given by (

114) and (115).

Corollary 5. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115), where ϕ is the stochastically stabilizing feedback control law given by (111) with and where is a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function that satisfies (105)–(109). Assume that is asymptotically zero state observable. Furthermore, assume , where , , and , . Then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system has a structured disk margin . If, in addition, , then the nonlinear stochastic system has a disk margin Proof. The result is a direct consequence of Theorem 11. Specifically, if

,

, and

, then (

118) is trivially satisfied for all

. Now, the result follows immediately by letting

. □

Finally, we provide sector and gain margins for the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system

given by (

114) and (115).

Corollary 6. Consider the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system given by (114) and (115), where ϕ is a stochastically stabilizing feedback control law given by (111) with and where is a two-times continuously differentiable, radially unbounded function that satisfies (105)–(109). Furthermore, assume , where , , , and , . Then the nonlinear stochastic dynamical system has a sector (and hence, gain) margin . Proof. The result is a direct consequence of Theorem 13. Specifically, if

,

, and

, then (

125) is trivially satisfied for all

. Now, the result follows immediately by letting

. □