Abstract

This paper focuses on studying the oscillatory properties of a distinctive class of second-order advanced differential equations with distributed deviating arguments in a noncanonical case. Utilizing the Riccati method and the comparison method with first-order equations, in addition to other analytical methods, we have established criteria to test whether the solutions of the studied equation exhibit oscillatory behavior. To verify the validity of the results we obtained and determine their applicability, we present some examples to confirm the strength and accuracy of our proposed criteria.

Keywords:

second-order differential equation; oscillation; nonoscillation; advanced; distributed deviating arguments MSC:

34C10; 34K1

1. Introduction

The purpose of this research is to investigate the oscillatory behavior of the solutions of the following second-order advanced differential equations:

where represents a fraction of two positive odd numbers, and

- A1

- and does not vanish identically;

- A2

- and has nonnegative partial derivatives.

By a solution of (1), we mean a real-valued function that satisfies (1) on , , and . We consider only those solutions P of (1) that satisfy

The study of oscillations in second-order differential equations holds a pivotal position in mathematical analysis and its applications. Second-order differential equations, which include classical equations of motion, vibration, and wave phenomena, serve as fundamental models in physics, engineering, and other applied sciences. The behavior of the solutions of these equations, particularly their oscillatory nature, reveals critical insights into the periodicity, stability, and resonant properties of the models they represent.

Oscillations in differential equations refer to repetitive variations in the solutions as they traverse through their equilibrium points. These oscillatory behaviors are not only mathematically intriguing but also practically significant. For instance, in mechanical systems, understanding the oscillatory response is essential for predicting the natural frequencies and preventing resonant failures. In electrical circuits, oscillations determine signal propagation and filter design, whereas in biological systems, rhythmic patterns such as heartbeats and neural oscillations are modeled by second-order differential equations [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The foundational theory of oscillations in second-order differential equations was established through the works of pioneers such as Jacob Bernoulli, Leonhard Euler, and Carl Gustav Jacobi. Their contributions laid the foundation for modern techniques in analyzing oscillatory behavior, including qualitative methods, phase plane analysis, and the theory of dynamical systems. Despite these advances, the quest to comprehend the full spectrum of oscillatory phenomena continues to drive contemporary research.

Ordinary differential equations (ODEs) serve as a fundamental tool in understanding and modeling various natural and engineering systems. Despite their widespread use, the complexity and diversity of real-world phenomena often need the introduction of advanced arguments into ODEs to achieve more accurate and comprehensive solutions. The importance of incorporating advanced arguments into ODEs has emerged through, among other things, the behavior exhibited by many nonlinear systems, which cannot be adequately captured by traditional linear differential equations. Advanced nonlinear dynamics allows for a more realistic representation of these systems, leading to better predictions and insights. Furthermore, perturbation methods allow for the analysis of systems subject to small perturbations, providing a means to understand the behavior of complex systems under different conditions. Furthermore, stability analysis is crucial for determining the long-term behavior of ODE solutions, which is essential in fields such as control theory and epidemiology. In recent years, the introduction of advanced arguments into ordinary differential equations has significantly improved our ability to tackle problems by using, for instance, nonlinear dynamics, perturbation methods, stability analysis, and numerical techniques. By integrating these advanced methods, researchers can address challenges such as nonlinearity, sensitivity to initial conditions, and the presence of multiple time scales, which are prevalent in many practical problems [7,8,9,10].

There are two main methods used to determine oscillation criteria for differential equations: the comparison principle method and the Riccati method. The comparison principle method provides a framework for comparing the solutions of differential equations with the solutions of simpler associated differential equations. By identifying the boundaries and relationships between these solutions, sufficient conditions for oscillation can be derived, allowing researchers to infer the behavior of complex systems from more solvable systems. This method relies heavily on the properties of the functions involved and their interactions over time. On the other hand, the Riccati method transforms the original differential equations into a Riccati-type differential equation. This approach takes advantage of the properties of Riccati equations, which have been extensively studied and have established techniques for analyzing their solutions. By converting differential equations into this form, results from Riccati equation theory can be applied to derive oscillation criteria [11,12,13,14].

Both methods contribute valuable insights into the oscillatory phenomena of advanced differential equations, providing researchers with powerful tools for analyzing the stability and dynamics of systems. The comparative strengths and applications of these methods highlight the richness of the techniques available for studying differential equations, ultimately enhancing our understanding of their complex behaviors.

Baculíková et al. [15] and Kusano and Naito [16] analyzed the oscillation of the differential equation

by various techniques in two cases, for

and

Chatzarakis [17] established some properties and relationships that led to achieving the conditions for oscillatory behavior in the half-linear differential equation

where

and

By using standard techniques, the author in [18] was able to reduce the order of the advanced differential equation

and derive some criteria that ensure the oscillation of its solutions.

In [19], the author studied the oscillatory behavior of the equation

assuming (2) and using the condition

to ensure the exclusion of nonoscillatory decreasing solutions.

From the above, most studies have provided results concerning Equation (1) in the presence of either condition (4) or (5) (see [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]). We also noticed that few results subject to (6) are given when (7) holds.

The primary objective of this paper is to study the oscillatory behavior of the solutions of (1) by eliminating the possibility of the existence of nonoscillatory (positive) increasing or decreasing solutions. Unlike most previous studies, we have managed to provide criteria to ensure the oscillation of all solutions of (1) under a single condition. In contrast, previous results either ensured the oscillation of all solutions under two conditions or provided results that guarantee that the solutions of (1) are either oscillatory or tend to zero.

The development of new and distinguished relationships to link the solutions of (1) with their higher-order derivatives has provided us with suitable tools to derive new conditions that differ in nature from those appearing in the previous literature. Consequently, our results expand and enhance previous results given in [7,8,9,16,27,28,29].

2. Main Results

For the sake of brevity, we define the following notations that will be used throughout the paper:

and

Lemma 1.

- , and

on with

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on . From (1), we have

That is, or . Suppose that (11) holds, and there is such that on .

From (1), we have

Define

In view of (12) and (13), we have

By integrating both sides of this inequality from to ⊤, we obtain

From (11), (14) leads to a contradiction with . Thus, cannot hold. Hence, P satisfies the first part of . Since is nonincreasing, we have

from which we arrive at

The proof is complete. □

Theorem 1.

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on From (17) and (2), we know that is unbounded, and thus, (11) holds. In view of Lemma 1, we see that holds for . Since , there exists such that

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on Then, for . Note that (11) is required for Equation (23) to be true. In view of the fact that

and (2), the integral

is unbounded, and so (11) must be satisfied. Then, by Lemma 1, holds for . According to , it is observed that there is such that

Substituting (25) into (1), we obtain

By integrating the above inequality from to ⊤, we have

or

By integrating (27) from to ⊤ and using (23), we obtain

This contradiction completes the proof. □

Proof.

We proceed by contradiction. Let us assume that (28) is false, that is,

Suppose that is a solution of (1) on Then, for . Note that (11) is required for (28) and (2) to be true. By Lemma 1, holds for . Integrating (1) from to ⊤ and having in mind that , we obtain

and then

By Lemma 1, we arrive at (15), which, together with (29), produces

which contradicts

This completes the proof of the theorem. □

Proof.

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on Then, for . We note that (32) and (2) give (11). Also, (32) implies

From (24) and (33), we find that (11) is satisfied. By Lemma 1, holds. From (1) and (15), we note that the advanced differential inequality

has a solution where Furthermore, the condition

implies the oscillation of (34) according to ([30] Theorem 2.4.1). That is, (1) does not admit a positive solution . This concludes the proof. □

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on Then, for . Similar to Theorem 6, this indicates that (35) and (2) lead to (11). By Lemma 1, we see that holds for . It is clear that

Applying the chain rule, we obtain

and

which, by (1), leads to

Let us define the decreasing function

Integrating (36) from ⊤ to ∞ and using (15), we have

This implies

Thus,

Taking into account (1), we find that the advanced differential inequality

has a solution . From ([30] Theorem 2.4.1), we find that the condition

implies the oscillation of (38). That is, (1) does not admit a positive solution , which is a contradiction. The proof is complete. □

Lemma 2

([31] Lemma 2.3). Let

with , and with and being real constants. Then, g attains its maximum value at

and

Theorem 7.

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on Then, for . From Lemma 1, we find that holds. Moreover, from (15), we can define a nonnegative function

which verifies

In view of (1) and , we obtain

which, with (42), gives

Taking

in (39), we arrive at

Integrating (44) from to ⊤, we obtain

From (41), we obtain

This contradiction completes the proof of the theorem. □

Proof.

Lemma 3.

Proof.

From Lemma 1, we find that holds. Using (1), (15), and (51), we have

Hence, it is

which produces

Using property (55), we obtain

It is clear that

and thus, we have

which leads to

and thus,

As in the proof of Theorem 1, we arrive at (22), that is,

Using inequality (59) in the equality

and using (52), we obtain

Therefore, is nonincreasing. This ends the proof. □

Theorem 8.

Proof.

Assume that satisfies Equation (1) on Then, for . We find that (23) requires (11) to be held. Note that (2) gives

That is, the function

is unbounded. Thus, must be unbounded, and we find that holds. Integrating (1) from to ⊤ and using Lemma 3, we conclude that

and consequently,

that is,

Using (61) in (58), we obtain

which produces

or

This completes the proof. □

Proof.

Theorem 10.

Proof.

3. Examples and Remarks

Example 1.

Consider the following advanced differential equation:

We see that

We can conclude the following:

- 1:

- According to Theorem 1,A lower bound of the solution is , and an upper bound of the solution is where and are positive constants.

- 2:

- According to Theorem 2, (23) does not apply; so, Theorem 2 fails.

- 3:

- According to Theorem 3, all solutions of (65) oscillate if

- 4:

- According to Theorem 5, all solutions of (65) are oscillatory if

- 5:

- According to Theorem 6, all solutions of (65) are oscillatory if

- 6:

Example 2.

Consider the advanced differential Equation (65) in the linear case as follows:

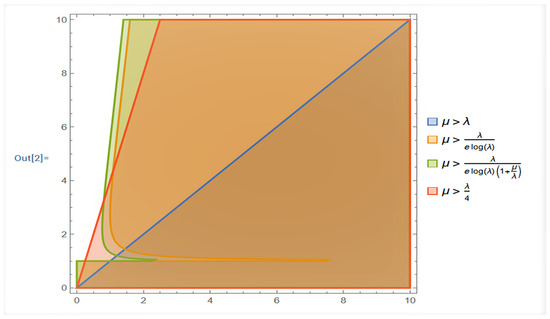

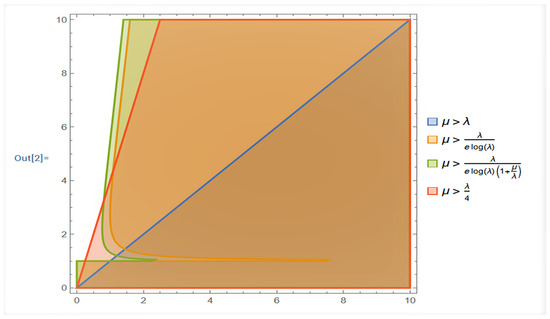

By applying the results obtained in Example 1 as a special case ( for (65) and by taking certain values for λ, we obtain the oscillation criteria for (70) (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Test of the quality of criteria for Equation (70).

Table 1.

The most effective theorems according to the change in the values of .

Remark 2.

We note that both Theorems 5 and 6 fail to apply when while condition (69) resulting from Theorem 7 leads to

and this is considered a sharp criterion for the Euler equation.

Example 3.

Remark 3.

From the above example, we find that Theorem 8, Theorem 9, and Theorem 10 improve the results stated in Theorem 3, Theorem 5, and Theorem 7, respectively.

Example 4.

Consider the following advanced differential equation:

Clearly,

We can conclude the following:

Remark 4.

Most of the previous literature that studied special cases of (1) shows results that ensure the oscillation of the solutions of the studied equations under two conditions. For example, the author of [19] studied Equation (9) and provided condition (10) to guarantee the exclusion of nonoscillatory decreasing solutions. Subsequently, using various methods, different conditions were provided to exclude nonoscillatory increasing solutions. Thus, the results given in [19] require two conditions, whereas we used a single condition to ensure the exclusion of all nonoscillatory solutions (see Theorems 2, 3, 5, and 6).

Furthermore, the use of the generalized Riccati assumption in Theorem 3, in the presence of the function , offers us multiple opportunities to test the oscillation of (1) (see Theorem 7 and Corollary 1).

4. Conclusions

Studying the behavior of solutions to equations in a noncanonical case is more challenging than in a canonical case due to the difficulty in establishing relationships between the solution and its various derivatives. These relationships are crucial for obtaining criteria to exclude the possibility of multiple derivative-positive, nonoscillatory solutions. By employing the Riccati method and the comparison principle, along with other analytical methods, we obtained different criteria. We presented distinctive results that do not require additional restrictions, as is usually the case in most previous studies. We provided a single criterion that ensures the exclusion of the possibility of nonoscillatory solutions of the increasing/decreasing positive type.

In addition, concerning future research, we see an opportunity to expand the scope of this study. We specifically suggest exploring the possibility of applying the same methods to establish criteria for the oscillation of neutral differential equations of the form

This expansion could contribute to enhancing the applicability of the methods established in this paper to a broader range of differential equations, thereby promoting ongoing advancement in this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A., H.R. and B.Q.; methodology, Z.A., B.Q. and A.A.; validation, Z.A., B.Q. and A.A.; investigation, Z.A., B.Q. and A.A.; resources, B.Q. and Z.A.; data curation, Z.A., B.Q. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.A., A.A., H.R. and B.Q.; writing—review and editing, B.Q., Z.A., A.A. and H.R.; visualization, Z.A., A.A. and B.Q.; supervision, A.A., H.R., Z.A. and B.Q.; project administration, B.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R518), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R518), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Erbe, L.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, B. Oscillation Theory for Functional Differential Equations; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rihan, F.A. Delay Differential Equations and Applications to Biology; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J.K. Functional differential equations. In Oxford Applied Mathematical Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Philos, C.G. On the existence of nonoscillatory solutions tending to zero at ∞ for differential equations with positive delays. Arch. Math. 1981, 36, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Grace, S.R.; O’Regan, D. Oscillation Theory for Difference and Functional Differential Equations; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzhansky, M.; Cho, Y.J.; Agarwal, P.; Area, I. Advances in Real and Complex Analysis with Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Bohner, M.; Li, T.; Zhang, C. Even-order half-linear advanced differential equations: Improved criteria in oscillatory and asymptotic properties. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 266, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džurina, J. Oscillation of second order differential equations with advanced argument. Math. Slovaca 1995, 45, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Jadlovská, I. Iterative oscillation results for second-order differential equations with advanced argument. Electron. J. Diff. Equ. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Zhang, C.; Li, T. New Kamenev-type oscillation criteria for second-order nonlinear advanced dynamic equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 225, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadlovská, I.; Chatzarakis, G.E.; Tunç, E. Kneser-type oscillation theorems for second-order functional differential equations with unbounded neutral coefficients. Math. Slovaca 2024, 74, 637–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.; Ali, A.H.; Bazighifan, O.; Iambor, L.F. Oscillatory Properties of Fourth-Order Advanced Differential Equations. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldiaiji, M.; Qaraad, B.; Iambor, L.F.; Elabbasy, E.M. New Oscillation Theorems for Second-Order Superlinear Neutral Differential Equations with Variable Damping Terms. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaraad, B.; Bazighifan, O.; Nofal, T.A.; Ali, A.H. Neutral differential equations with distribution deviating arguments: Oscillation conditions. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2022, 21, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baculíková, B.; Džurina, J.; Graef, J.R. Oscillation criteria for second-order linear differential equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2002, 271, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kusano, T.; Naito, M. Comparison theorems for functional differential equations with deviating arguments. J. Math. Soc. Jpn. 1981, 33, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Grace, S.R.; Jadlovská, I.R.E.N.A. A sharp oscillation criterion for second-order half-linear advanced differential equations. Acta Math. Hung. 2021, 163, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džurina, J. A comparison theorem for linear delay differential equations. Arch. Math. Brno. 1995, 31, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, T.S. Kamenev-type oscillation criteria for second order nonlinear dynamic equations on time scales. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 217, 5285–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Rogovchenko, Y.V. Oscillation of second-order neutral differential equations. Math. Nachr. 2015, 288, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Rogovchenko, Y.V. Oscillation criteria for second-order superlinear Emden-Fowler neutral differential equations. Monatsh. Math. 2017, 184, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trench, W.F. Canonical forms and principal systems for general disconjugate equations. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 1973, 189, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Rogovchenko, Y.V.; Zhang, C. Oscillation results for second-order nonlinear neutral differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2013, 2013, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Thandapani, E.; Graef, J.R.; Tunc, E. Oscillation of second-order Emden–Fowler neutral differential equations. Nonlinear Stud. 2013, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Zhang, C.; Li, T. Some remarks on oscillation of second order neutral differential equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2016, 274, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moaaz, O.; Elabbasy, E.M.; Qaraad, B. An improved approach for studying oscillation of generalized Emden–Fowler neutral differential equation. J. Inequal. Appl. 2020, 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplatadze, R.; Kvinikadze, G.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Properties A and B of n th order linear differential equations with deviating argument. Georgian Math. J. 1999, 6, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baculíková, B. Oscillatory behavior of the second order functional differential equations. Appl. Math. Lett. 2017, 72, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Grace, S.R.; O’Regan, D. Oscillation Theory for Second Order Dynamic Equations; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; p. 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladde, G.S.; Lakshmikantham, V.; Zhang, B.G. Oscillation Theory of Differential Equations with Deviating Arguments; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 110. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Erbe, L.; Peterson, A. Oscillation of solution to second-order half-linear delay dynamic equations on time scales. Electron. J. Diff. Equ. 2016, 2016, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).